Abstract

Electrophysiological techniques were used to assess the generalizability of concreteness effects on word processing across word class (nouns and verbs) and different types of lexical ambiguity (syntactic only and combined syntactic/semantic). The results replicated prior work in showing an enhanced N400 response and a sustained frontal negativity to concrete as compared with abstract nouns. The effect of concreteness on the N400 generalized to all word class and ambiguity conditions, whereas the frontal effect was present for all word types except for the syntactically and semantically ambiguous items when these were used as verbs. The seemingly dissociable ERP effects of concreteness at frontal and central/posterior electrode sites revealed by these data suggest that concreteness may impact multiple aspects of neurocognitive processing.

Keywords: Language, Concreteness effects, Word class, Word class ambiguity, Noun–verb homonymy, ERPs

1. Introduction

Linguistic concreteness—i.e., the extent to which an expression describes a concept that can be perceived by the senses—is a factor known to have robust effects on various cognitive processes, including perceptual selectivity, paired-associate learning, recognition memory, and language (see review by Paivio and colleagues, 1968). In the domain of language processing, for example, it has been found that concrete words are responded to more quickly in lexical decision tasks (Schwanenflugel, Harnishfeger, & Stowe, 1988) and are read aloud more accurately and with less semantic errors by deep dyslexic patients (Gerhand & Barry, 2000). Such effects also hold at the sentence level: concrete sentences are comprehended more quickly and accurately than abstract sentences (Haberlandt & Graesser, 1985; Schwanenflugel & Shoben, 1983) and are responded to faster in meaningfulness judgment (Holmes & Langford, 1976) and truthfulness judgment tasks (Belmore, Yates, Bellack, Jones, & Rosenquist, 1982).

Several hypotheses have been put forward to account for the processing advantages observed for concrete words. In his dual coding theory, Paivio (1969, 1971, 1991) held that imagery was the critical factor, with concrete words accruing a processing advantage by virtue of the fact that they can be accessed via both the verbal system (also used to store and process abstract words) and the imagery system. In contrast, under unitary semantic system accounts, the concreteness advantage comes from the richer availability of contextual information for concrete words (Schwanenflugel, 1991; Schwanenflugel et al., 1988). Support for this hypothesis comes from studies showing that whereas concreteness effects are robust for words out of context or in random sentential/paragraph contexts, effects are attenuated in coherent contexts or upon repetition, when both concrete and abstract words can be accessed with sufficient contextual information (James, 1975; Marschark, 1985; Paivio, Clark, & Khan, 1988; Schwanenflugel & Shoben, 1983; Wattenmaker & Shoben, 1987).

Recent neurophysiological studies that have attempted to adjudicate between these two theories have instead uncovered data patterns suggestive of an account that combines elements of both views. Holcomb and colleagues, in a series of event-related potential (ERP) studies (Holcomb, Kounios, Anderson, & West, 1999; Kounios & Holcomb, 1994; West & Holcomb, 2000), found that concrete words were associated with more negative-going potentials, beginning in the time window of the N400 component (~250–450 ms post-stimulus onset) and continuing to up to 800 ms. This concreteness-based difference was most pronounced over frontal scalp sites (whereas, in general, N400 effects have a centro-posterior focus). However, when concrete and abstract words were put into predictive sentence contexts (Holcomb et al., 1999) or were repeated (Kounios & Holcomb, 1994), such differences were strongly attenuated.

The scalp distributional differences between concrete and abstract words support dual coding accounts in suggesting that different neural resources are involved in processing the two categories of words. On the other hand, the results also make clear that contextual manipulations can modulate this effect. Moreover, the fact that differences are observed in the time window of the N400—a component that has been strongly linked to semantic processing (Kutas & Federmeier, 2000)—is suggestive that the concreteness effect may be at least partially based on the richness of the words’ semantic associations. Based on their findings, Holcomb and colleagues have proposed the “context extended dual-coding hypothesis”, which states that a complete account of concreteness effects must include not only multiple semantic codes for representing and processing the two different word types, to account for the topographic differences, but also a contextual component, to account for the context-based modulations (Holcomb et al., 1999).

Although the ERP pattern associated with concreteness is now fairly well-established, the underlying nature of the frontal negativity is not. Holcomb and colleagues raised this point and suggested that the distribution of the negativity in the N400 time region might reflect the contribution of multiple semantic memory processes, including a posterior ‘linguistically sensitive N400’, activated by both concrete and abstract words, and a more frontal ‘imagistically sensitive N400’, which is exclusively activated by the concrete words (Holcomb et al., 1999). This hypothesis is consistent with data showing that the N400 response to pictorial stimuli seems to be more frontally distributed than the typical N400 to words (Holcomb & McPherson, 1994; McPherson & Holcomb, 1999). However, in addition to explaining the effect of concreteness on the distribution of the response during the N400 time window, it is also necessary to account for the sustained nature of the frontal effect. Based on an experiment that manipulated task demands across groups (including a surface task, a semantic task, and an imagery task), West and Holcomb (2000) have hypothesized that, in addition to effects of concreteness on the semantic processes reflected in the N400 component, there are imagery-related processes that contribute to the concreteness effect, which manifest as a later frontal negativity they termed the “ N700”.

Sustained frontal negativities have also sometimes been seen in response to other word-related manipulations. For example, in a study investigating semantic and word class ambiguity (Lee & Federmeier, 2006), we found a similar frontal slow negativity to words that are both word class ambiguous and semantically ambiguous (e.g., the duck/to duck) as compared with unambiguous nouns and verbs (e.g., the sofa/to eat) and word class ambiguous items with little semantic ambiguity (e.g., the vote/to vote). The frontal negativity started from about 250 ms after stimulus onset and continued to the end of the one-second epoch. Our study did not initially build in a control for concreteness, though the ambiguity effect seemed to hold in post hoc analyses in which concreteness could be matched. Interestingly, some of the items used in previous concreteness studies were word class and semantically ambiguous: for example, ‘rose’ (Holcomb et al., 1999) and ‘table’ (Kounios & Holcomb, 1994). The similarity of the waveform patterns across the two sets of experiments raises interesting questions about the role of concreteness and semantic/syntactic ambiguity—and possible interactions between these factors—in driving the slow frontal effect.

In order to examine the relationship between concreteness and ambiguity, it is also necessary to further consider the factor of grammatical class. This is because the kind of ambiguity that has been shown thus far to produce sustained frontal effects (similar to those seen for concreteness differences) occurred across different word class uses of a single lexical item (e.g., the duck/to duck; Lee & Federmeier, 2006). In general, nouns and verbs differ along various dimensions, including average frequency, age of acquisition, lexical neighborhood density, number of semantic associates, mutability of meanings and potential lexical competitors for a given word (Gentner, 1981; Szekely et al., 2005), and word class differences are apparent for many aspects of language processing, including children’s lexical development (Gentner, 1982), aphasic patients’ deficit patterns (Myerson & Goodglass, 1972), and healthy adults’ memory for words (Reynolds & Flagg, 1976) and electrophysiological responses (Federmeier, Segal, Lombrozo, & Kutas, 2000; Lee & Federmeier, 2006), among others. Interestingly, the electrophysiological word class effects seem to vary as a function of ambiguity. In their studies, Federmeier et al. (2000) and Lee and Federmeier (2006) found that, irrespective of word class ambiguity, nouns tend to elicit larger N400s than do verbs. However, the most prominent word class effect—a frontal positivity (300–700 ms) to verbs as compared with nouns—was found only for class unambiguous items. Word class ambiguous words did not show this effect, even when embedded in verb-predicting contexts (i.e., “to eat” yielded this positivity, whereas “ to drink” did not). Most importantly for the present study, the noun and verb senses of a given ambiguous lexical item are likely to be associated with different concreteness values (e.g., in our norming study, described below, the word ‘swamp’ was rated as quite concrete in its noun sense [5.9 on a 7 point scale], but much less concrete in its verb sense [3.2]). Thus, in order to examine concreteness effects for word class ambiguous items, it is necessary to obtain word class specific concreteness ratings and to specify the word class use of all lexical items within the experimental context. Indeed, as described next, prior work suggests that concreteness effects may manifest differently as a function of both word class and lexical ambiguity.

Most studies in the literature have used only nouns as stimuli, leaving open the question of whether the kind of concreteness effects that have typically been described generalize to other parts of speech. However, a few studies that included verbs in their stimulus sets have reported interactions of concreteness with word class. For example, Yuille and Holyoak (1974) investigated the influence of concreteness on memory performance using sentences of the following structure: “ The (adjective) (noun) (past tense verb) the (adjective) (noun)”; the concreteness of both the subject and object nouns and the verbs was manipulated. Recognition for the sentences (with foils involving swaps of the subject and object noun or of the entire noun phrase) and recall were tested in two separate experiments. The results showed that sentences containing concrete noun phrases, in comparison with those containing abstract noun phrases, were both recognized and recalled more accurately, whereas the concreteness of the verbs did not affect either measure. Yuille and Holyoak interpreted their results as suggesting that noun concreteness was a much more critical determinant of sentence imagery and memory, though they pointed out that the range of concreteness in their stimulus set was greater for the nouns than for the verbs, which may explain the difference in data patterns for the two word classes. In a lexical decision task using a visual half-field manipulation, Eviatar, Menn, and Zaidel (1990) found a similar pattern, with concreteness effects for nouns—but not for verbs—observed in both visual fields. However, as footnoted by the authors, the verbs in this study were actually word class ambiguous; inspection of their stimuli further suggests that at least some of the items were also semantically ambiguous. This might have contributed to the different patterns they found for nouns and verbs.

Lexical ambiguity across word classes may also account for the differing pattern of concreteness by word class interactions that have been reported in studies using different languages within the ERP literature. On the one hand, Zhang, Guo, Ding, and Wang (2006), using a lexical decision task with Chinese two-character words, found a typical concreteness effect for nouns. High concrete nouns were associated with a larger negativity (broadly distributed, but larger over the front of the head) in the N400 time window (200–500 ms). However, for verbs, a much smaller and distributionally constrained concreteness effect was found, which only approached statistical significance at some central electrode sites. Thus, the results of this study concur with the behavioral findings in suggesting that concreteness effects are absent—or greatly reduced—for verbs. On the other hand, however, Kellenbach, Wijers, Hovius, Mulder, and Mulder (2002), using a recognition memory task in German, found that concreteness had similar effects on both nouns and verbs, with more negative responses between 300 and 750 ms over anterior electrode sites for words with rich visual or motor semantic attributes. The authors did notice a tendency for this effect to be reduced for verbs in comparison with nouns, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. One possible explanation for the fact that concreteness effects manifested differently across word class in Chinese but not in German is that these languages differ in whether words are likely to be class ambiguous. Whereas many words in Chinese are word class ambiguous (and this class ambiguity may further involve semantic ambiguity), morphologically rich languages such as German do not readily allow for such ambiguity. It is possible that concreteness effects unfold differently in the presence of ambiguity, and that, in turn, these effects of ambiguity are different for nouns and verbs. In fact, similar inconsistencies in the pattern of concreteness effects can also be seen in the hemodynamic imaging literature (e.g., Bedny & Thompson-Schill, 2006; Perani et al., 1999), and some have suggested that such differences arise in part because of the differing number of senses associated with ambiguous lexical items when these are used as verbs versus when used as nouns (Bedny & Thompson-Schill, 2006).

In sum, the pattern of findings across the literature suggests that both grammatical class and lexical ambiguity may influence concreteness effects, highlighting the need to jointly examine these factors within a single language, stimulus set, and participant group in order to more systematically assess the generalizability of concreteness effects. To that end, the current study measured ERP responses while jointly manipulating word class, semantic/syntactic ambiguity, and concreteness. As in prior work (Federmeier et al., 2000; Lee & Federmeier, 2006), we examined brain responses elicited by unambiguous nouns (e.g., sofa), unambiguous verbs (e.g., eat), word class ambiguous words with similar meanings across their noun and verb senses (e.g., vote), and word class ambiguous words that were also semantically ambiguous (e.g., duck). Each of these classes was further subdivided into high and low concreteness sets of words, based on concreteness norming that took word class into consideration for class ambiguous items (something prior published norms have not done). Word class was primed by preceding each target with a noun- or verb-predictive function word (i.e., ‘the’ or ‘to’). In light of previous findings suggesting that concreteness effects are more robust in tasks that require semantic processing (James, 1975; Kounios & Holcomb, 1994; West & Holcomb, 2000), a semantic-relatedness judgment task was used in the current design. Our aim was to see whether a concreteness effect manifests for all grammatical classes and ambiguity conditions and, if so, to compare the time-course and distribution of the ERP responses in order to determine if the nature of concreteness effects is unitary or dependent upon word type.

If concreteness effects arise because of inherent differences in the kind of semantic information made available by concrete versus abstract items (as the context availability hypothesis would seem to suggest), then we should expect such effects to hold across factors like word class and ambiguity, especially when measured on a functionally specific component, the N400, that indexes the availability of such information. If, instead, concreteness effects arise when additional processes (such as imagery) are brought to bear for concrete, but not abstract, words, then it is possible that concreteness could interact with factors such as word class and/or ambiguity if, for example, participants are more likely to image objects than actions or if ambiguity resolution delays the implementation of such processes. Given that there are suggestions of multiple subcomponents of the ERP concreteness effect, it is further possible that different aspects of the response (e.g., the N400 and the slow frontal negativity) may be differentially sensitive to these factors, allowing these subcomponents to be more definitively separated. Finally, the differences in the results of the Kellenbach et al. (2002) and the Zhang et al. (2006) studies for concreteness effects on verbs, seen across languages that vary in degree of lexical ambiguity, leads to the specific prediction that concreteness effects for verbs in the present study may be more sensitive to ambiguity than concreteness effects for nouns.

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials

Three types of words were used in this study: (1) word class unambiguous words (UW), including class unambiguous nouns (UN; e.g., the sofa) and class unambiguous verbs (UV; e.g., to eat), (2) syntactically ambiguous but semantically unambiguous words (AU), which can be used as both nouns (AU-N; e.g., the vote) and verbs (AU-V; e.g., to vote) but have little or no semantic ambiguity (i.e., the noun and verb senses refer to very similar concepts, as determined by norming data described in our previous study: Lee & Federmeier, 2006), and (3) syntactically and semantically ambiguous words (AA), which can be used as both nouns and verbs (AA-N; e.g., the duck and AA-V; e.g., to duck) and have a high degree of semantic ambiguity (i.e., the noun and verb senses have very different meanings).

For each word type (UN, UV, AU-N, AU-V, AA-N, AA-V), we obtained a high and low concreteness sample, using concreteness ratings obtained in a norming session (described below). Appendix A shows examples of each of the stimulus types. Table 1 (nouns) and Table 2 (verbs) give the ranges of concreteness difference and the mean values and standard deviations of relevant lexical features for each word type. Concreteness values were matched across word class and ambiguity type for both the high and low concreteness samples, with a significant overall difference in concreteness ratings between the high and low concreteness items (p < .0001),1 but no difference across word types (p > .05). Because the distribution of the words along the dimensions of concreteness and other lexical features is different for the two word classes (in particular, more concrete verbs tend to be less frequent; see Szekely et al., 2005, for a extensive discussion of the inherent differences in the distribution of lexical variables across word classes), it was not possible to match the items perfectly across all features. For this reason, log frequencies were matched separately within each word class. The noun conditions were controlled for log frequency across concreteness level and ambiguity type (p > 0.8). High concrete verbs were overall slightly less frequent than low concrete verbs (p < .05); however, within a concreteness level, they did not differ across ambiguity type (p > .7).2 Note that word frequency is known to impact the amplitude of the N400 (to words out of context), but has never been associated with slow frontal effects.

Table 1.

Mean values (with standard deviations in parentheses) of lexical features for noun subtypes; concreteness ranges are specified at the bottom of the table

| Noun subtypes | Concreteness | Log frequency | Word length | Semantic similarity | No. of items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UW | High concreteness | 5.84 (0.51) | 1.72 (0.38) | 5 (0.8) | N/A | 30 |

| Low concreteness | 3.81 (0.71) | 1.68 (0.37) | 5 (0.8) | N/A | 30 | |

| AU | High concreteness | 5.85 (0.48) | 1.70 (0.40) | 5 (1.4) | 4.9 (0.5) | 30 |

| Low concreteness | 3.82 (0.36) | 1.69 (0.48) | 5 (1.6) | 5.0 (0.5) | 30 | |

| AA | High concreteness | 5.85 (0.42) | 1.68 (0.35) | 4 (1.4) | 2.8 (0.8) | 30 |

| Low concreteness | 3.82 (0.56) | 1.69 (0.49) | 5 (1.6) | 3.3 (0.7) | 30 | |

Concreteness difference between high and low sets: UW: 2.03; AU: 2.03; AA: 2.03.

Table 2.

Mean values (with standard deviations in parentheses) of lexical features for verb subtypes; concreteness ranges are specified at the bottom of the table

| Verb subtypes | Concreteness | Log frequency | Word length | Semantic similarity | No. of items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UW | High concreteness | 5.77 (0.31) | 1.40 (0.51) | 5 (0.9) | N/A | 17 |

| Low concreteness | 3.75 (0.34) | 1.70 (0.36) | 6 (1) | N/A | 17 | |

| AU | High concreteness | 5.80 (0.29) | 1.57 (0.58) | 5 (1.1) | 5.1 (0.5) | 30 |

| Low concreteness | 3.72 (0.33) | 1.65 (0.48) | 5 (1.5) | 5.1 (0.5) | 30 | |

| AA | High concreteness | 5.77 (0.26) | 1.34 (0.67) | 4 (1) | 2.9 (0.8) | 30 |

| Low concreteness | 3.46 (0.34) | 1.75 (0.57) | 5 (1.6) | 3.3 (0.6) | 30 | |

Concreteness difference between high and low sets: UW: 2.02; AU: 2.08; AA: 2.31.

Target words were embedded in a minimal phrase context, consisting of one of two types of syntactic cues: the noun-biasing cue ‘the’ or the verb-biasing cue ‘to’. Unambiguous items were paired only with the grammatically coherent cue. Across the stimulus set, each of the word class ambiguous words was used once as a noun and once as a verb. However, words were split into two lists such that an individual participant saw each class ambiguous word only once. Word length, frequency, and concreteness values were controlled within each list. Trials were randomized once for each list and presented to participants in the same order.

2.2. Concreteness rating

Concreteness ratings for each word used in the study were obtained in a paper and pencil norming study. Forty monolingual English speakers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (16 men and 24 women, mean age 18, range 18–21) participated for course credit (none of these participants was in the ERP study). The stimuli used in the norming procedure were 650 words, including 125 word-class-unambiguous nouns, 125 word-class-unambiguous verbs, and 400 word-class-ambiguous words. All words were preceded by either ‘the’ or ‘to’ so that class ambiguous words could be rated separately for their noun and verb senses. Words were divided into two lists, each containing 125 class-unambiguous words and 400 class ambiguous words, such that across the lists all items appeared in all possible forms, but within a list each class ambiguous word was used only once. Participants were instructed to use a 1–7 scale in order to rate the concreteness of the first meaning that they thought of when they saw each word in its phrase. A rating of “7” indicated that the meaning “can be experienced directly by the senses” (and thus that the word is highly concrete; e.g., ‘the chair’ or ‘to shovel’), while a rating of “1” indicated that the meaning “cannot be experienced directly by the senses” (and thus that the word is highly abstract; e.g., ‘the liberty’ or ‘to appeal’). As described previously, the norming data were used to select a final set of AA, AU, UN, and UV words for the ERP experiment.

2.3. Participants

Thirty UIUC undergraduate students (12 males and 18 females, mean age 20, range 18–25) participated in this study for cash or course credit. All participants were right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh inventory (Oldfield, 1971); 12 reported having left handed family members. No participant had a history of neurological/psychiatric disorders, and all were monolingual speakers of English with no consistent exposure to other languages before age 5. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two lists.

2.4. Procedure

Participants were seated 100 cm in front of a 21” computer monitor in a dim, quiet testing room. An 18-trial practice session was used to familiarize participants with the task and the experimental environment. At the start of each trial, four horizontally adjacent plus signs appeared in the center of the screen for 500 ms. After an SOA ranging randomly between 1000 and 1500 ms (a random SOA was used in order to decrease the contribution of slow, anticipatory activity to the ERP), the cue (either “to” or “the”) and the target word were presented one word at a time in the center of the screen, each for 200 ms with a 500 ms SOA. One thousand milliseconds after the offset of the target, a semantic judgment probe (described below) was presented on one-third of the trials and the capitalized message ‘NEXT TRIAL’ on the other two-thirds of the trials. In both cases, the phrase was displayed as a whole in red color and remained on the screen until the participant’s response. The next trial began after a delay of 2.5 s.

Because the literature suggests that concreteness effects are more robust for tasks that require semantic processing (James, 1975; Kounios & Holcomb, 1994; West & Holcomb, 2000), a semantic-relatedness judgment task was used to ensure that participants were attending to the experiment and were processing the stimuli for meaning. Participants were told that a probe phrase would appear unpredictably after some of the trials and that their task was to decide whether the probe phrase was semantically related or unrelated to the word in the immediately preceding phrase. Participants registered their response using one of two hand-held buttons; response hand for “yes” and “no” was counterbalanced across participants. Half of the probe trials were semantically related to the target word in the sense specified by the syntactic cue (e.g., the phrase ‘to box’ followed by the judgment probe ‘to hit’) and the other half were unrelated to any sense of the target word (e.g., the phrase ‘the permit’ followed by the judgment probe ‘the towel’). The function word (“the” or “to”) used in the probe phrase was always the same as the one in the immediately preceding trial, so that the probe phrases would not draw special attention to the potential ambiguity of the words. When trials were not followed by a judgment probe, participants could initiate the next trial by pressing either button.

2.5. EEG recording parameters

The electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded from twenty-six geodesically arranged silver/silver-chloride electrodes attached to an elastic cap. The twenty-six sites included Midline, Left and Right Medial, and Left and Right Lateral Prefrontal (MiPf, LMPf, RMPf, LLPf, RLPf), Medial, Mediolateral, and Lateral Frontal (LMFr, RMFr, LDFr, RDFr, LLFr, RLFr), Midline, Medial, and Mediolateral Central (MiCe, LMCe, RMCe, LDCe, RDCe), Midline and Mediolateral Parietal (MiPa, LDPa, RDPa), Lateral Temporal (LLTe, RLTe), and Midline, Medial, and Lateral Occipital (MiOc, LMOc, RMOc, LLOc, RLOc) electode locations. All scalp electrodes were referenced on-line to the left mastoid and re-referenced off-line to the average of the right and the left mastoids. In addition, one electrode was placed on the left infraorbital ridge to monitor the vertical EOG, and a bipolar montage of electrodes was placed on the outer canthus of each eye to monitor the horizontal EOG. Electrode impedances were kept below 3 kΩ. The continuous EEG was amplified with Sensorium amplifiers using an analog bandpass of 0.02–100 Hz, sampled at 250 Hz, and stored on a hard disk for later analyses.

2.6. Data analysis

Epochs of EEG data were taken from 100 ms before stimulus onset to 920 ms after. Those containing artifacts from amplifier blocking, signal drift, excessive eye movements, or muscle activity were rejected off-line before averaging. Trials contaminated by eye blinks were corrected for 14 participants who had enough blinks to obtain a stable filter (Dale, 1994) for all other participants, trials with blink artifacts were dropped. Trial loss averaged 10%. Averages of artifact-free ERPs were created for each type of target word after subtraction of the 100 ms pre-stimulus baseline. Prior to measurement, ERPs were digitally filtered with a bandpass of 0.2–20 Hz.

3. Results

3.1. Behavior

The purpose of the behavioral task was to ensure that participants attended to the stimuli and processed the words for meaning. Indeed, participants performed well: mean accuracy across participants and conditions was 92.6%, and accuracy for all subconditions was over 85% (UN, 95%; AU-N, 91%; AA-N, 91%; UV, 94%; AU-V, 88%; AA-V, 94%).

3.2. ERPs

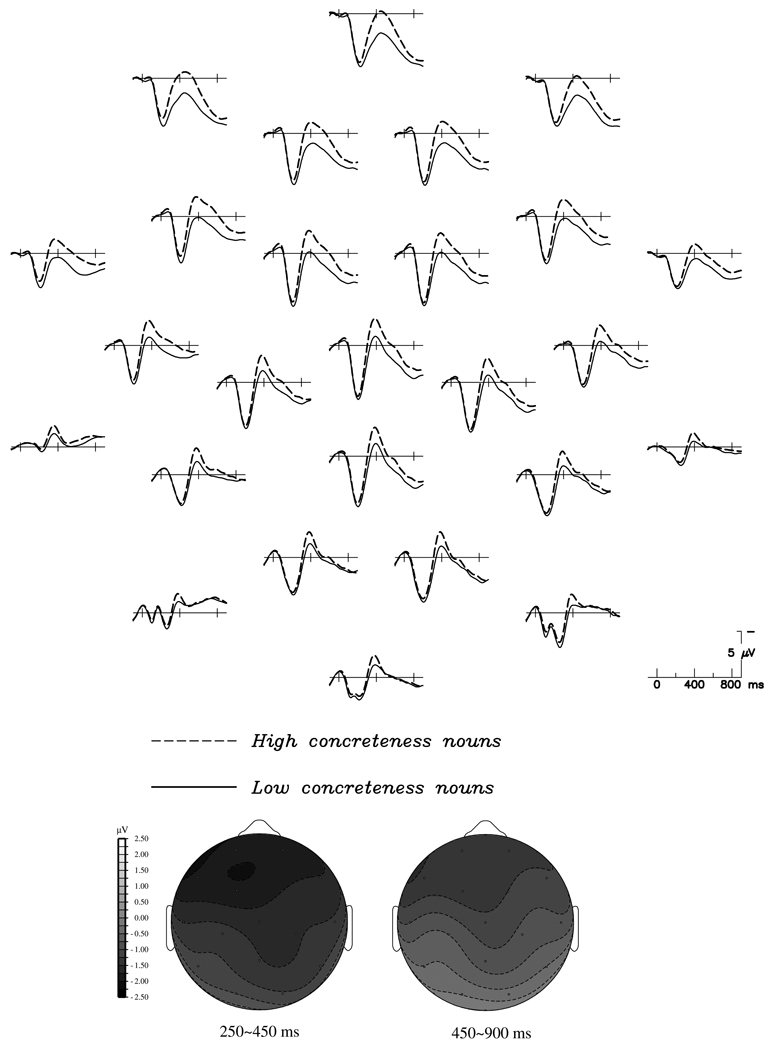

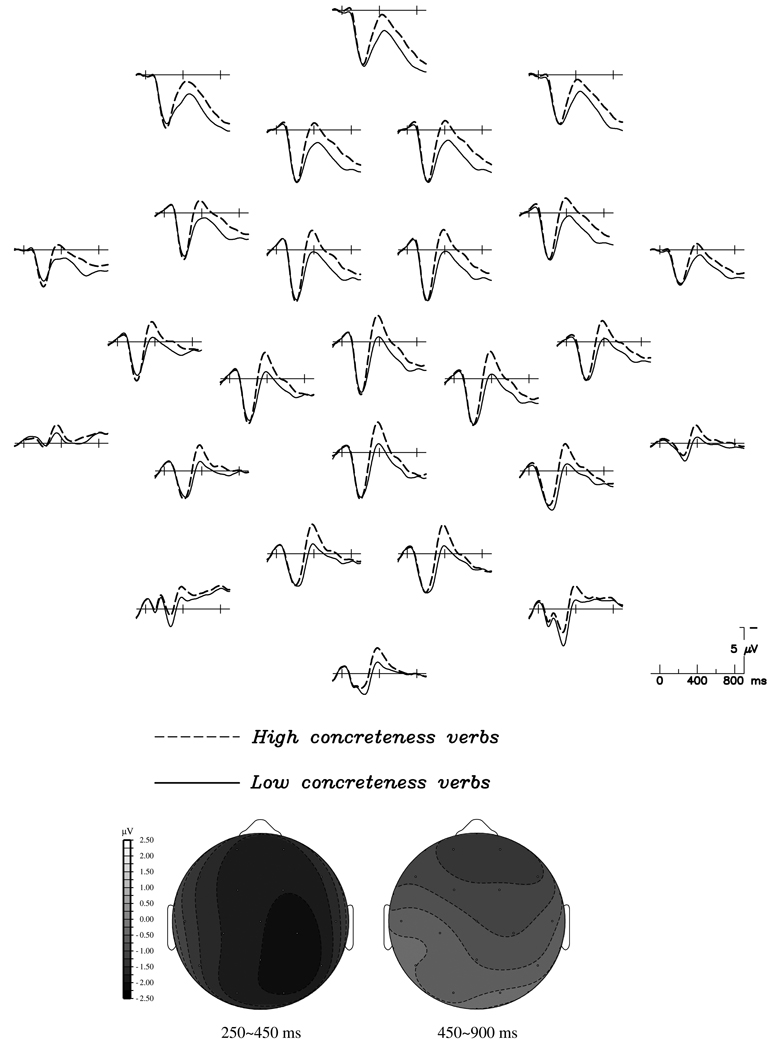

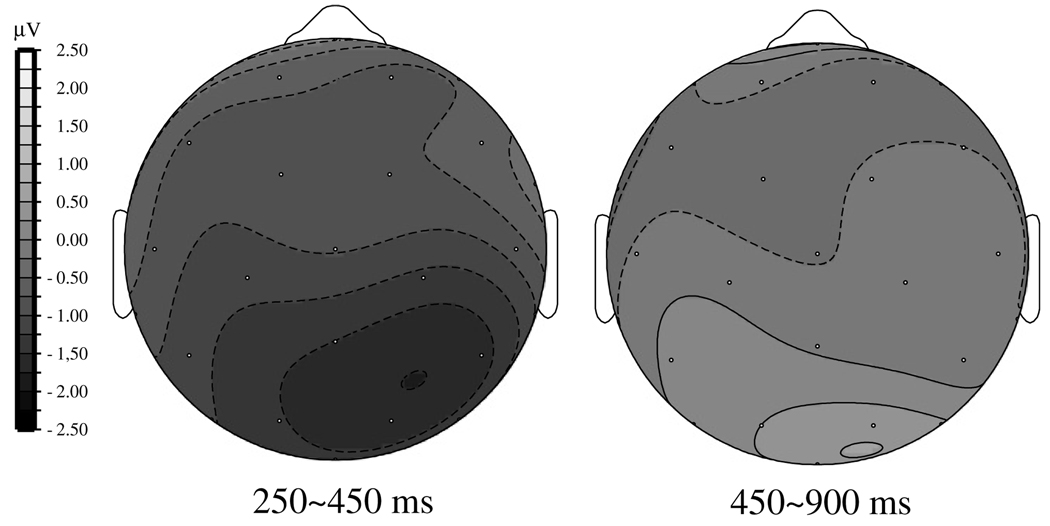

Fig. 1 shows grand average ERPs at all 26 scalp channels for high and low concreteness nouns, collapsed across ambiguity condition. Fig. 2 shows the same comparison for verbs. All conditions are characterized by early components typical of visual word presentation. These include, over posterior sites, a positivity (P1) peaking around 100 ms, a negativity (N1) peaking around 175 ms, and a positivity (P2) peaking around 200–250 ms, as well as, over frontal sites, a negativity (N1) peaking around 100 ms and a positivity (P2) peaking around 200 ms. These responses are followed by a broadly distributed negativity with a central–posterior focus peaking around 400 ms (N400). N400 responses appear to be larger (more negative) for high than for low concrete words, for both noun and verb classes. Over frontal sites, the difference due to concreteness appears to extend to later parts of the epoch.

Fig. 1.

Grand average ERPs at all electrode sites to high concreteness nouns (dashed line) and low concreteness nouns (solid line), collapsed across ambiguity type. Negative is plotted up for this figure and all subsequent ones. The response to high concreteness nouns (e.g., ‘desk’) is more negative than the response to low concreteness nouns (e.g., ‘logic’) over both frontal and posterior channels, beginning around 250 ms after stimulus onset. The negativity over central–posterior sites peaks around 400 ms (N400), whereas over frontal sites the difference due to concreteness extends to later parts of the epoch. At bottom, isopotential voltage maps viewed from the top of the head show distribution of the concreteness effect in the 250–450 ms and 450–900 ms time windows.

Fig. 2.

Grand average ERPs at all electrode sites to high concreteness verbs (dashed line) and low concreteness verbs (solid line), collapsed across ambiguity type. The response to high concreteness verbs (e.g., ‘speak’) is more negative than the response to low concreteness verbs (e.g., ‘vary’). This effect for verbs is similar to that seen for the nouns. At bottom, isopotential voltage maps viewed from the top of the head show the distribution of the concreteness effect in the 250–450 ms and 450–900 ms time windows. The effect distribution is similar to that seen for nouns, though in the 250–450 ms time window the posterior part of the effect appears to be stronger for verbs (such that the distribution shows less of a frontal skew).

Voltage maps of the concreteness effect for nouns and verbs (bottom of Fig. 1 and Fig 2) suggest effect patterns similar to those seen in prior reports (Holcomb et al., 1999; Kounios & Holcomb, 1994; West & Holcomb, 2000), with a widely distributed, slightly frontal negative effect between 250 and 450 ms followed by a negative effect limited to frontal sites in the later part of the recording epoch (450–900 ms). The distribution of the concreteness effect was assessed with a omnibus analysis of variance (ANOVA) with two levels of time window (250–450 ms and 450–900 ms), two levels of concreteness (high and low, collapsed over word type), five levels of anteriority (Prefrontal, Frontal, Central, Temporal /Parietal, and Occipital), and five levels of electrode. The results showed significant main effects of time window [F(1, 29) = 4.2; p < .05] and concreteness [F(1, 29) = 32.75; p < .0001], modulated by an interaction of the two [F(1,29) = 23.46; p < .0001]; effects were larger overall in the 250–450 ms time window. Anteriority interacted with both time window [F(4, 116) = 4.04; p < .05] and concreteness [F(4, 116) = 11.42; p = .0001], and the three way interaction was also significant [F(4, 116) = 5.49; p < .01]. In both time windows, the concreteness effect was largest toward the front of the head; however, this anterior skew was greater in the 450–900 ms time window (mean amplitudes of the concreteness effect from front to back of the head in the 250–450 ms time window were 1.73, 1.54, 1.60, 1.24, and 1.26 µV and in the 450–900 ms time window were 1.30, 1.09, 0.86, 0.50, and 0.27 µV). This pattern may indicate that concreteness effects show up over posterior sites as amplitude changes on the N400 (250–450 ms) and over frontal sites in the form of a sustained negativity (250–900 ms).

Motivated by the outcome of the distributional analysis, electrode sites were divided into frontal and posterior regions for more focused analyses across conditions. Posterior effects were examined in the N400 time window (250–450 ms) at the 15 central/posterior channels (MiCe, LMCe, RMCe, LDCe, RDCe, MiPa, LDPa, RDPa, LLTe, RLTe, MiOc, LMOc, RMOc, LLOc, and RLOc). Frontal effects were examined in both the N400 time window (250–450 ms) and the later part of the epoch (450–900 ms) at the 11 frontal channels (MiPf, LMPf, RMPf, LLPf, RLPf, LMFr, RMFr, LDFr, RDFr, LLFr, and RLFr). For each analysis of variance (ANOVA), the Huynh–Feldt adjustment to the degrees of freedom was applied to correct for violations of sphericity associated with repeated measures. Accordingly, for all F tests with more than 1 degree of freedom in the numerator, the uncorrected degrees of freedom, and the corrected p value are reported. Effect size (ω2) measures are also given for each comparison. Interactions with electrode site are reported only when of theoretical significance.

3.3. Central–posterior effects

In order to examine effects of concreteness on the N400 component, an ANOVA with two levels of concreteness (high concrete/low concrete), two levels of word class (nouns/verbs), three levels of ambiguity (AA/AU/UW), and 15 levels of electrode (central–posterior sites) was conducted on mean amplitudes between 250 and 450 ms after stimulus onset. There were significant main effects of concreteness [F(1, 29) = 38.38; p < .0001; ω2 = 0.141] and ambiguity [F(2, 58) = 4.01; p < .05; ω2 = 0.017] but not of word class [F(1, 29) = 0.05; p = .82; ω2 = 0]. Word class and ambiguity interacted [F(2, 58) = 3.36; p < .05; ω2 = 0.013], reflecting a larger ambiguity effect for verbs. In addition, there was also a marginal concreteness by word class interaction [F(1, 29) = 3.77; p = .06; ω2 = 0.005] (as can be seen in the voltage maps in Fig. 1 and Fig 2; this difference might have arisen because for verbs, but not for nouns, there were unavoidable word frequency differences between the high and low concreteness sets, which would be expected to affect N400 amplitudes to these items). Overall, consistent with past findings, responses were more negative for high than for low concrete words and tended to be more negative for words with semantic ambiguity (AA) than for words without (UW and AU).

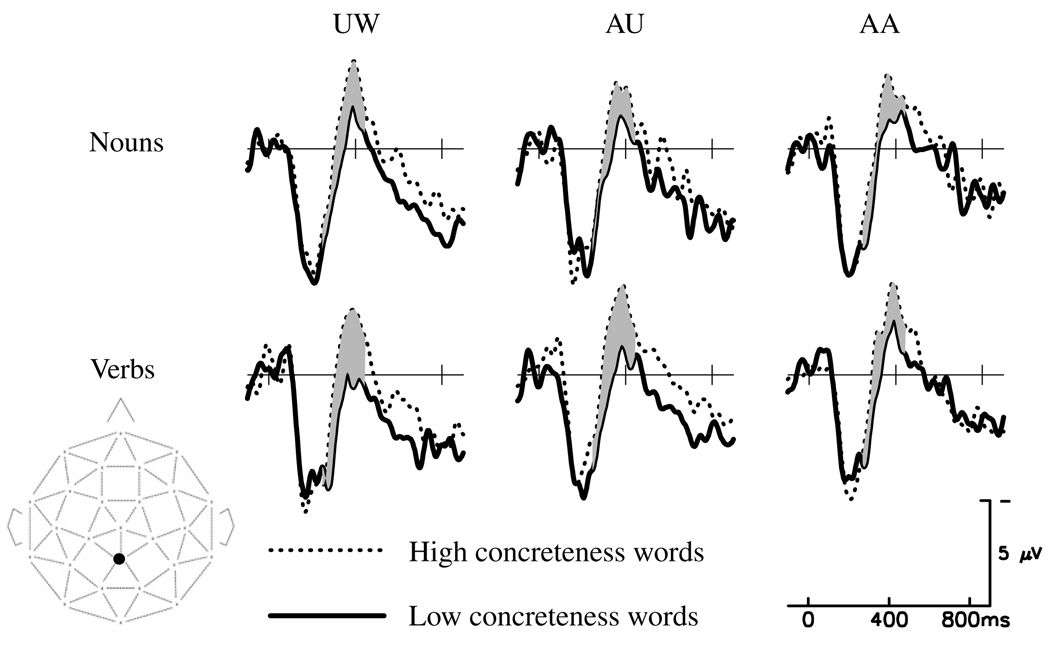

Table 3 shows the outcomes of planned comparisons of high and low concreteness words for each item subtype. All comparisons were significant except for AU-N, which was only marginally significant. The marginal effect for AU-N became significant if a more restricted time range (300–450 ms) and a slightly smaller set of electrode sites (excluding LLOc and RLOc, where N400 effects are not typically prominent) was analyzed: [F(1,29) = 4.11; p = .05; ω2 = 0.04]. Fig. 3 overlaps the response for high and low concreteness words in each subclass for each series at the middle parietal site.

Table 3.

Statistical outcomes of planned comparisons on concreteness for word subtypes at central–posterior electrode sites

| 250–450 ms | |

|---|---|

| UN | [F = 11.15; p < .005; ω2 = 0.07] |

| AU-N | [F = 2.57; p = .12; ω2 = 0.02] |

| AA-N | [F = 7.13; p = .01; ω2 = 0.04] |

| UV | [F = 21.31; p = .0001; ω2 = 0.17] |

| AU-V | [F = 12.86; p = .001; ω2 = 0.13] |

| AA-V | [F = 6.6; p < .05; ω2 = 0.05] |

Degrees of freedom for all F tests were (1, 29).

Fig. 3.

Overlapped are the ERP responses to high concrete words (dotted line) and low concrete words (solid line) in each subclass at a representative medial posterior electrode. The position of the plotted site is indicated by the black dot on the small head diagram. Effects of concreteness over posterior sites emerged for all word types.

In summary, high concrete words elicited a larger negativity than did low concrete words over central and posterior electrode sites in the typical N400 time window (250–450 ms). This effect was evident for all word class and ambiguity subconditions (though the effect for AU-N words was more restricted in its time course and distribution).

3.4. Frontal effects

An ANOVA with two levels of concreteness (high concrete/low concrete), two levels of word class (nouns/verbs), three levels of ambiguity (AA/AU/UW), and 11 levels of electrode (frontal sites) was conducted on mean amplitudes between 250 and 450 ms after stimulus onset. The results revealed significant main effects of concreteness [F(1, 29) = 41.58; p < .0001; ω2 = 0.19] and word class [F(1, 29) = 4.8; p < .05; ω2 = 0.02] and a marginally significant effect of ambiguity [F(2, 58) = 2.79 p = .07; ω2 = 0.01]. The three variables (concreteness, word class and ambiguity) also showed a marginal interaction [F(2, 58) = 2.45; p = .09; ω2 = 0.01]. Similar to the pattern observed over central/posterior sites in this time window, more concrete words were associated with more negative-going potentials, and words with both semantic and syntactic ambiguity (AA) were also more negative than the other two word types (AU and UW); consistent with past findings, nouns were also more negative than verbs.

The same analysis performed on mean amplitudes between 450 and 900 ms again revealed main effects of concreteness [F(1, 29) = 23.96; p < .0001; ω2 = 0.1] and word class [F(1,29) = 5.96; p < .05; ω2 = 0.02] and a marginally significant effect of ambiguity [F(2, 58) = 2.59; p = .08; ω2 = 0.01]. The effects of these variables in this time window followed the same pattern as in the 250–450 ms time window.

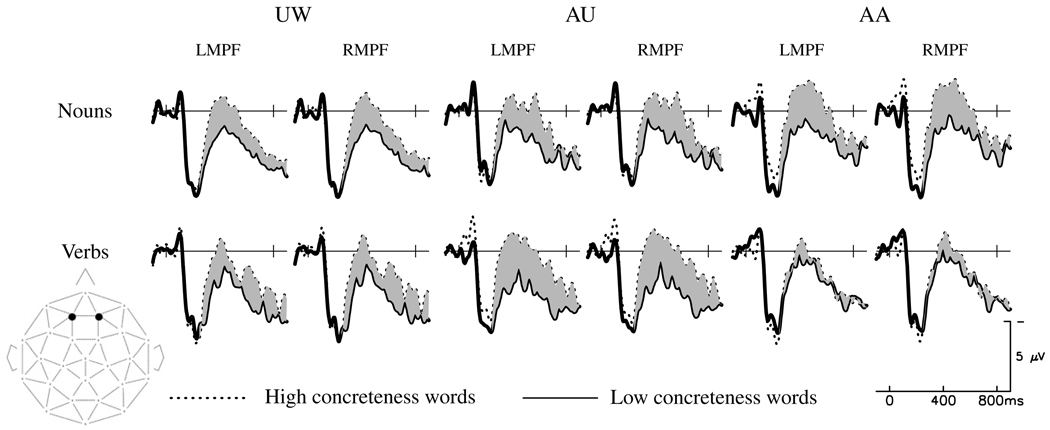

Table 4 shows the outcomes of planned comparisons of high and low concreteness words for each item subtype. Reliable concreteness effects were seen for all types of nouns (UN, AU-N, AA-N) in both time windows. In contrast, for verbs, the effect was significant in both time windows for UV and AU-V items. However, for AA-V words, the effect was not significant or marginal in either epoch. Fig. 4 overlaps the response for high and low concreteness words in each subclass at two representative frontal sites.

Table 4.

Statistical outcomes of planned comparisons on concreteness for word subtypes at frontal electrode sites

| 250–450 ms | 450–900 ms | |

|---|---|---|

| UN | [F = 15.91; p < .001; ω2 = 0.13] | [F = 9.24; p =.005; ω2 = 0.06] |

| AU-N | [F = 5.56; p < .05; ω2 = 0.06] | [F = 6.63; p < .05; ω2 = 0.05] |

| AA-N | [F = 17.97; p < .001; ω2 = 0.14] | [F = 8.85; p < .01; ω2 = 0.07] |

| UV | [F = 9.71; p < .005; ω2 = 0.11] | [F = 7.17; p = .01; ω2 = 0.06] |

| AU-V | [F = 15.68; p < .001; ω2 = 0.17] | [F = 8.78; p < .01; ω2 = 0.10] |

| AA-V | [F = 0.89; p = .35; ω2 = 0.00] | [F = 0.21; p = .65; ω2 = 0.00] |

Degrees of freedom for all F tests were (1, 29).

Fig. 4.

Overlapped are the ERP responses to high concrete words (dotted line) and low concrete words (solid line) in each subclass at two representative prefrontal electrodes. Positions of the plotted sites are indicated by black dots on the small head diagram. Frontal concreteness effects were absent for syntactically and semantically ambiguous items used as verbs.

In summary, over the frontal part of the scalp, high concrete words were associated with a larger prolonged (250–900 ms) negativity than low concrete words. This difference was seen for all subtypes of nouns, for unambiguous verbs, and for words with syntactic, but not semantic, ambiguity used as verbs (AU-V). However, when syntactically and semantically ambiguous words were used as verbs (AA-V), effects of concreteness were not apparent in either time window.

Fig. 5 shows voltage maps of the AA-V condition in the two analysis time windows. Unlike the corresponding voltage maps for the other conditions (see Fig. 1 and Fig 2), effects for AA-V manifest solely as a posterior negativity in the 250–450 ms time window, with a distribution characteristic of N400 effects. To further test the apparent difference in the distribution of the response to the AA-V condition, we directly compared the concreteness effect (250–900 ms) for the AA items when used as verbs versus when used as nouns. An ANOVA with factors concreteness (high concrete/low concrete), word class (AA-N/AA-V), anteriority (five levels, from prefrontal to occipital sites) and electrode site (five levels) yielded a significant three way interaction between concreteness, word class, and anteriority [F(4, 116) = 4.52; p = .02; ω2 = 0.01]. Whereas the concreteness effect for the AA items used as nouns was widespread, encompassing both posterior and frontal sites (and actually largest at frontal sites), the concreteness effect for the AA items used as verbs was limited to central–posterior sites.

Fig. 5.

Isopotential voltage maps viewed from the top of the head show the concreteness effect distribution (250–450 ms and 450–900 ms) for semantically and syntactically ambiguous items used as verbs. Different from the responses to all other word types, AA-V items elicited a posteriorally distributed concreteness effect between 250 and 450 ms, with a distribution typical of that for the N400. No frontally distributed negativity was observed in either time window.

4. Discussion

Concreteness effects have been robustly demonstrated for nouns in behavioral studies (Hamilton & Rajaram, 2001; Paivio, Walsh, & Bons, 1994; for review, see also Paivio, Yuille, & Madigan, 1968), hemodynamic imaging studies (Jessen et al., 2000; Sabsevitz, Medler, Seidenberg, & Binder, 2005), and electrophysiological studies (Holcomb et al., 1999; Kounios & Holcomb, 1994; West & Holcomb, 2000). However, the basis (or bases) of these effects, and their generalizability, has remained unclear. On the one hand, it is possible that concreteness effects arise from general properties of words, such as the richness of the semantic information they evoke, in which case such effects would be expected to hold across word class and other lexical variables. On the other hand, concreteness effects might arise when additional processes, such as imagery, are brought to bear in a task- or stimulus-dependent manner, in which case there might be interactions between concreteness and variables such as grammatical class.

Indeed, across the prior literature, there are suggestions that both word class and lexical ambiguity may affect the expression of concreteness effects. Zhang et al. (2006) found an interaction between concreteness and word class in the ERP responses to Chinese words of high and low concreteness. For nouns, higher concreteness values were associated with greater amplitude responses during the N400 time window (250–450 ms), especially notable over frontal channels, and enhanced negativity over frontal sites continuing in time windows beyond the N400. In contrast, effects for verbs were quite small and limited to posterior electrode sites. However, word class did not interact with concreteness in a study using a recognition memory task with German words (Kellenbach et al., 2002). In that study, for both nouns and verbs, words with rich visual or motor semantic attributes elicited more negative ERP responses between 300 and 750 ms over anterior electrode sites. A similar pattern of mixed results has been seen in hemodynamic imaging studies: in a PET study, Perani and colleagues (1999) found no interaction of word class and concreteness, whereas a recent fMRI study (Bedny & Thompson-Schill, 2006) did find interactions of word class and imageability (a factor generally considered similar to and highly correlated with concreteness; Paivio et al., 1968) in brain areas including the left inferior frontal and middle temporal gyri. For this latter data, the results of a regression analysis that looked at both imageability ratings and the number of semantic senses associated with the nouns and verbs led the authors to suggest that the concreteness by word class interactions may have been driven by word-class-correlated differences in semantic processing (such as the number of distinct meanings and concomitant selection requirements) rather than by differential impact of imageability per se.

Such disparities in the findings across the literature emphasize the need for a better understanding of how concreteness effects might be modulated by factors such as word class and lexical/semantic ambiguity. To that end, the goal of the present study was to use electrophysiological measures to examine concreteness effects in tandem with word class and ambiguity in a single language, stimulus set, and participant group. Therefore, we assessed concreteness effects for unambiguous English nouns and verbs as well as for word class ambiguous words used as nouns and verbs. This latter class provides an important test case, since it allows one to differentiate the effects of being used as a noun or a verb from specific lexical or semantic properties that might adhere to unambiguous nouns or verbs. Furthermore, word class ambiguous items vary in how semantically ambiguous they are across their noun and verb senses, providing the opportunity to examine the interaction of concreteness with semantic ambiguity. Each type of word was divided into a high and low concreteness set based on norming values collected separately for noun senses and verb senses. Target words were preceded by a syntactic cue (a noun- or verb-predictive function word: ‘the’ or ‘to’), which established the most likely grammatical class of the target word, and participants made semantic-relatedness judgments to a subsequent probe (since semantic tasks have been associated with the most robust concreteness effects). We examined concreteness effects for each type of word in the 250–450 ms window over posterior sites, where N400 effects are typically most prominent, and in both 250–450 and 450–900 ms time windows over frontal sites, where sustained effects of concreteness have been previously observed for nouns. Effects of concreteness were evident for all types of words in all conditions. However, there were differences in the specific pattern of concreteness effects across word types.

Over central–posterior sites, enhanced N400 responses to concrete, as compared with abstract, words were evident for all word class and ambiguity conditions. Because the N400 has been closely linked to semantic access and integration processes (reviewed by Kutas & Federmeier, 2000), concreteness-based effects on the N400 seem likely to be mediated by semantic features of the words. For example, highly concrete words may be associated with a richer set of semantic associations than less concrete words. This hypothesis is bolstered by prior work showing that N400 concreteness effects are more robust for tasks that tap more heavily into semantic processing (Kounios & Holcomb, 1994; West & Holcomb, 2000). This kind of account is also supported by findings from a recurrent connectionist model by Plaut and Shallice (1993), which successfully simulated the classic concreteness effect in deep dyslexia (in which concrete words are more likely to be read correctly than abstract words); in that model, concreteness was defined as the number of associated semantic features.

However, a different pattern emerged over frontal sites. For all types of nouns (UN, AU-N, AA-N), higher concreteness was associated with enhanced negativity, beginning in the N400 time window and continuing throughout the one-second epoch. A similar effect was seen for unambiguous verbs (UV) and for syntactically (but not semantically) ambiguous words used as verbs (AU-V). However, strikingly, no frontal concreteness effects emerged for syntactically and semantic ambiguous items used as verbs (AA-V). Thus, similar to the Kellenbach et al. (2002) findings in German, a morphologically rich language in which word class ambiguity (and associated semantic ambiguity) is unlikely, we find that verbs in English do manifest concreteness effects, as long as they are not semantically ambiguous. The response to the semantically ambiguous verbs in the present study was, however, similar to that observed more globally to Chinese verbs in Zhang et al.’s (2006) study, in that the AA-V items elicited concreteness effects that were limited to posterior channels in the N400 time window. It is possible that the pattern in the Zhang et al. (2006) study reflects a similar effect of word class and ambiguity. Zhang et al. (2006) did not specifically manipulate or control for ambiguity, but, because of the sparse morphological marking system in Chinese, it is the case that many Chinese words are potentially class ambiguous. Indeed, one survey (Huang, Chu-Ren, & Chang, 2002) of a million word Chinese corpus found that more than 50% of the words used were class ambiguous (though this figure included repeated uses of highly frequent words). If the words in the Zhang et al. (2006) study were similarly likely to be syntactically ambiguous—and if these also had some degree of semantic ambiguity (it is not possible to determine this from their report)—then the findings seem parallel. The results are also consistent with those of behavioral studies using word class ambiguous verbs (with some degree of semantic ambiguity), which also failed to find concreteness effects (Eviatar et al., 1990).

Our results thus show that, on the one hand, verbs can elicit the kind of concreteness effects previously documented for nouns and that syntactically ambiguous words can elicit concreteness effects when used in either noun-predicting or verb-predicting contexts. On the other hand, however, it also seems to be the case that concreteness effects are modulated by both word class and ambiguity, since syntactically and semantically ambiguous items fail to show frontal concreteness effects, but only when these items are placed in a verb-predicting context. Why the AA-V words selectively fail to show this concreteness effect is unclear and warrants further study. Because concreteness is linked to word meaning, it seems likely that meaning selection will need to be completed before at least some of the processes underlying concreteness effects can unfold. In particular, the frontal negativity associated with concreteness has been linked by some to imagery (West & Holcomb, 2000), and this may be one such process that cannot proceed until the meaning competition engendered by a semantically ambiguous lexical item has been resolved. It is possible that ambiguity resolution takes longer, or is somehow more difficult, when a lexical item is used as a verb (perhaps because of the need to access argument structure information when verbs are accessed; e.g., Trueswell, 1996). Alternatively, there may be interactions between ambiguity resolution and imagery processes that are more prominent for verbs. Imaging a verb, for example, would often seem to involve concomitant imagery for the nouns involved in the action, and this could be impacted by the need to suppress noun-related meanings during ambiguity resolution. Finally, it may be that the verb-predicting cue (‘to’) used in this study was less effective than the noun-predicting cue (‘the’) at constraining the class of the upcoming target word.

In conclusion, we replicated prior work showing that concreteness effects manifest as an enhanced N400 response over posterior electrode sites and a sustained frontal negativity. In our data, these two aspects of the concreteness effect dissociated, with the posterior response showing up for all word class and ambiguity conditions, but the frontal response absent for syntactically and semantically ambiguous items used as verbs. Based on the present data alone, it is not possible to definitively determine whether the concreteness effects obtained in the early (250–450 ms) time window reflect a frontally distributed N400 or a normally (posteriorally) distributed N400 overlapping with the beginning of a sustained, frontal negativity. However, the fact that the AA-V items manifested a posterior concreteness effect in this time window but failed to elicit a frontal effect in either time window is more consistent with the latter view. If so, this suggests that concreteness has dissociable effects on the electrophysiological response to words, and, in turn, that it may impact multiple aspects of neurocognitive processing—e.g., possibly both the richness of the associated semantic information as well as the possibility/efficacy of the imagery processes elicited by these words—consistent with proposals such as that of Holcomb and colleagues (Holcomb et al., 1999).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan Garnsey, Cynthia Fisher, and Aaron Meyer for insightful comments on an earlier version of this article and Aubrey Lutz, Haq Wajid, and Sarah Baisley for help with data collection. This study was supported by NIA Grant AG26308 to KDF.

Appendix A

Appendix.

Sample experimental stimuli

| UN | UV | AU | AA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High concrete |

Low concrete |

High concrete |

Low concrete |

High concrete |

Low concrete |

High concrete |

Low concrete |

| desk | duty | bake | accept | bag | concern | bat | channel |

| dirt | error | carve | become | circle | despair | cut | condition |

| food | irony | chew | decide | dust | envy | duck | excuse |

| injury | logic | eat | develop | fight | hate | fall | fault |

| lung | loss | grow | differ | kick | hope | fan | keep |

| movie | manner | kneel | lend | smile | import | fly | permit |

| person | mood | see | relax | talk | plan | land | recall |

| road | origin | sit | remain | taste | shame | smoke | rule |

| text | skill | speak | vary | walk | stay | tap | spell |

| tube | truth | weep | warn | whisper | try | watch | trust |

Footnotes

The average concreteness value for the low concreteness items in the current study (3.73) is slightly higher than that for abstract items in prior studies: 2.93 in West and Holcomb (2000), 2.61 in Kounios and Holcomb (1994), and 2.52 in Holcomb et al. (1999). However, since these ratings come from different norming studies with different instructions (ours specified the word class use of all lexical items to be rated), it is not clear if the scores are completely comparable. To be cautious, we refer to our items as “low concreteness”, rather than as abstract.

Due to the difficulty of matching multiple lexical features across the many subtypes of words, the UV condition as analyzed had a slightly smaller number of stimuli than the other five. To mitigate concerns that differences might arise for this condition due to the smaller number of trials (and thus potentially different signal to noise ratio in the ERP to these items), we also analyzed results for a larger set of UV items that were matched to the other word types in stimulus number, mean concreteness, and other lexical variables such as word length and frequency, but that had a more restricted range of concreteness difference between the high and low samples. The effects reported below were the same for the UV items in the two sets, suggesting that the lower number of trials did not meaningfully affect the pattern of results.

References

- Bedny M, Thompson-Schill SL. Neuroanatomically separable effects of imageability and grammatical class during single-word comprehension. Brain and Language. 2006;98(2):127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmore SM, Yates JM, Bellack DR, Jones SN, Rosenquist SE. Drawing inferences from concrete and abstract sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1982;21:338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Source localization and spatial discriminant analysis of event-related potentials: Linear approaches. La Jolla, CA: University of California, San Diego; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eviatar Z, Menn L, Zaidel E. Concreteness: Nouns, verbs, and hemispheres. Cortex. 1990;26:611–624. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federmeier KD, Segal JB, Lombrozo T, Kutas M. Brain responses to nouns, verbs and class-ambiguous words in context. Brain. 2000;123(12):2552–2566. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. Some interesting differences between verbs and nouns. Cognitive and Brain Theory. 1981;4:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. Why nouns are learned before verbs: Linguistic relativity versus natural partitioning. In: Kuczaj SA, editor. Language Development. Language, Thought and Culture. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1982. pp. 301–334. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhand S, Barry C. When does a deep dyslexic make a semantic error? The roles of age-of-acquisition, concreteness, and frequency. Brain and Language. 2000;74(1):26–47. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberlandt KF, Graesser AC. Component processes in text comprehension and some of their interactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1985;114:357–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, Rajaram S. The concreteness effect in implicit and explicit memory tests. Journal of Memory and Language. 2001;44(1):96–117. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb PJ, Kounios J, Anderson JE, West WC. Dual-coding, context-availability, and concreteness effects in sentence comprehension: An electrophysiological investigation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1999;25(3):721–742. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.3.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb PJ, McPherson WB. Event-related brain potentials reflect semantic priming in an object decision task. Brain and Cognition. 1994;24:259–274. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1994.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes VM, Langford J. Comprehension and recall of abstract and concrete sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1976;15:559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Chu-Ren Huang, Ru-Yng Chang. Categorical ambiguity and information content a corpus-based study of Chinese. COLING post-conference workshop first SIGHAN workshop on Chinese language processing. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- James C. The role of semantic information in lexical decision. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1975;104:130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Heun R, Erb M, Granath D-O, Klose U, Papassotiropoulosa A, et al. The concreteness effect: Evidence for dual coding and context availability. Brain and Language. 2000;74(1):103–112. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenbach ML, Wijers AA, Hovius M, Mulder J, Mulder G. Neural differentiation of lexical-syntactic categories or semantic features? Event-related potential evidence for both. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;144:561–577. doi: 10.1162/08989290260045819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kounios J, Holcomb PJ. Concreteness effects in semantic processing: ERP evidence supporting dual-coding theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1994;20(4):804–823. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.20.4.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, Federmeier KD. Electrophysiology reveals semantic memory use in language comprehension. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4(12):463–470. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CL, Federmeier KD. To mind the mind: An event-related potential study of word class and semantic ambiguity. Brain Research. 2006;1081:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschark M. Imagery and organization in recall of prose. Journal of Memory and Language. 1985;24:734–745. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson WB, Holcomb PJ. An electrophysiological investigation of semantic priming with pictures of real objects. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:53–65. doi: 10.1017/s0048577299971196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson R, Goodglass H. Transformational grammars of three agrammatic patients. Language and Speech. 1972;15:40–50. doi: 10.1177/002383097201500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Mental imagery in associative learning and memory. Psychological Review. 1969;76:241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Imagery and verbal processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1991;45:255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A, Clark JM, Khan M. Effects of concreteness and semantic relatedness on composite imagery ratings and cued recall. Memory and Cognition. 1988;16:422–429. doi: 10.3758/bf03214222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A, Walsh M, Bons T. Concreteness effects on memory: When and why? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1994;20(5):1196–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A, Yuille JC, Madigan SA. Concreteness, imagery, and meaningfulness values for 925 nouns. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Monograph Supplement. 1968;76(1):1–25. doi: 10.1037/h0025327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut DC, Shallice T. Deep dyslexia: A case study of connectionist neuropsychology. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1993;10:377–500. [Google Scholar]

- Perani D, Cappa SF, Schnur T, Tettamanti M, Collina S, Rosa MM, et al. The neural correlates of verb and noun processing. A PET study. Brain. 1999;122(12):2337–2344. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.12.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, Flagg P. Recognition memory for elements of sentences. Memory and Cognition. 1976;4:422–432. doi: 10.3758/BF03213199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabsevitz DS, Medler DA, Seidenberg M, Binder JR. Modulation of the semantic system by word imageability. Neuroimage. 2005;27(1):188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel P. Why are abstract concepts hard to understand? In: Schwanenflugel P, editor. The psychology of word meanings. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel PJ, Harnishfeger KK, Stowe RW. Context availability and lexical decisions for abstract and concrete words. Journal of Memory and Language. 1988;27:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel PJ, Shoben EJ. Differential context effects in the comprehension of abstract and concrete verbal materials. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1983;9(1):82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Szekely A, D’Amico S, Devescovi A, Federmeier K, Herron D, Iyer G, et al. Timed action and object naming. Cortex. 2005;41:7–26. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueswell JC. The role of lexical frequency in syntactic ambiguity resolution. Journal of Memory and Language. 1996;35:566–585. [Google Scholar]

- Wattenmaker WD, Shoben EJ. Context and the recallability of concrete and abstract sentences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1987;13(1):140–150. [Google Scholar]

- West WC, Holcomb PJ. Imaginal, semantic, and surface-level processing of concrete and abstract words: An electrophysiological investigation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12(6):1024–1037. doi: 10.1162/08989290051137558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuille JC, Holyoak KJ. Verb imagery and noun phrase concreteness in the recognition and recall of sentences. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1974;28:359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Guo CY, Ding JH, Wang ZY. Concreteness effects in the processing of Chinese words. Brain and Language. 2006;96(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]