Abstract

Chromosomal organization is sufficiently evolutionarily stable that large syntenic blocks of genes can be recognized even between species as distantly related as mammals and puffer fish (450 Myr divergence)1–7. In Diptera the gene content of the X chromosome and the autosomes is well conserved: in Drosophila more than 95% of the genes have remained on the same chromosome arm in the 12 sequenced species (63 Myr of divergence, traversing 400 Myr of evolution)2,4,6, and the same linkage groups are clearly recognizable in mosquito genomes (260 Myr of divergence)3,5,7. Here we investigate the conservation of Y-linked gene content among the 12 sequenced Drosophila species. We found that only 1/4 of D. melanogaster Y-linked genes (3 out 12 ) are Y-linked in all sequenced species, and that the majority of them (7 out 12) were acquired less than 63 Myr ago. Hence, whereas the organization of other Drosophila chromosomes trace back to the common ancestor with mosquitoes, the gene content of the D. melanogaster Y is much younger. Gene losses are known to play a major role in the evolution of Y chromosomes8–10, and we indeed found two such cases. However, the rate of gene gain in the Drosophila Y chromosomes investigated is 10.9 times higher than the rate of gene loss (95% confidence interval: 2.3 – 52.5), and hence their gene content seems to be increasing. In contrast with the mammalian Y, gene gains have a prominent role in the evolution of the Drosophila Y chromosome.

Even in sequenced species little is known about the Y chromosomes, because their heterochromatic state precludes sequence assembly into large and easily studied scaffolds, but instead short Y-linked scaffolds must be individually identified11,12. In most Drosophila species the Y chromosome is essential for male fertility13, and genetic data have identified between six and ten Y-linked factors required for this function14,15. The paucity of genes and its heterochromatic state suggested that, like the mammalian Y16, the Drosophila Y might be largely a degenerated X chromosome. The conservation of the fertility function in rather distant species fits well with the known conservation of gene content of Drosophila chromosomal arms6,17. Hence sex-chromosome evolutionary theory8,9, well-known patterns of chromosome evolution in Drosophila, and conservation of biological function all suggest that the Drosophila Y ought to be a degenerated X, with a few remaining and well conserved genes. However, the 12 genes identified on the D. melanogaster Y were all acquired through gene duplications from the autosomes, rather than being a relic subset of the X-linked genes18–22. Furthermore, a Y-autosome fusion in the D. pseudoobscura lineage made the ancestral Y into part of an autosome, and a new Y chromosome arose23. Both findings suggest that Drosophila Y chromosomes are labile, and raise the question of how well conserved is their gene content.

The recent sequencing of 10 additional Drosophila genomes24 allows a detailed study of this question. We first identified the putative orthologs of the 12 known D. melanogaster Y-linked genes18–22 in the remaining species (Methods Summary). Due to the low coverage of the Y11 and its abundance of repetitive sequences, the sequences of almost all Y-linked genes have large gaps and sequencing errors, and different exons of the same gene are scattered in several scaffolds19,20 (Supplementary Fig. 1). These problems were corrected by direct sequencing of RT-PCR and RACE products (Methods Summary) for all genes; we sequenced ~ 150 kb, and the average gene has 1/3 of its sequence generated de novo (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, we could not find the orthologs of Pp1-Y1 gene in D. mojavensis or the orthologs of PPr-Y in D. grimshawi, even among the raw sequencing traces. Synteny analysis strongly suggests that the Pp1-Y1 loss is real; degenerate PCR with a primer pair that amplifies PPr-Y in a broad range of species confirmed its loss in D. grimshawi (Supplementary Discussion).

Molecular evolutionary analysis, revealing a substantial excess of synonymous over nonsynonymous changes in protein-coding genes, strongly suggests that all Y-linked genes are functional (Supplementary Table 2). Orthology was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis of all genes (Supplementary Fig. 2). We then tested their Y-linkage by PCR in males and females. Surprisingly, many of the genes are not Y-linked in several species (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 1). The results of D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis are expected, given the known Y-autosome fusion that occurred in this lineage23. The other linkage changes (Table 1) can be caused by individual movements of genes from the Y to other chromosomes or vice versa. Movement direction was unambiguously ascertained by synteny analysis even in the kl-5 gene, whose data implies two independent transfers to the Y chromosome (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Using synteny (Supplementary Fig. 4 to 8) and the known phylogenetic relationships among the sequenced species24, we could infer the direction and time of the gene movements, as shown in Fig. 2. Intron positions were conserved in all cases, which rules out retrotransposition, and suggest a DNA-based mechanism for the gene movements (Supplementary Discussion). Most or all extant genes were acquired individually by the Y chromosome (as opposed to resulting from large segmental duplications), since they are not adjacent to each other at their original autosomal locations (Supplementary Fig. 4 to 8; Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1. Y-linkage across the 12 Drosophila species of genes that are Y-linked in D. melanogaster.

Unabridged species names (in the order of appearance) are: D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. erecta, D. yakuba, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. persimilis, D. willistoni, D. mojavensis, D. virilis, and D. grimshawi. "+" Y-linked gene ; " − " autosomal or X-linked gene; "0" gene absent from the genome.

| Gene | mel | sim | ere | ana | pse | wil | moj | vir | gri |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sec | yak | per* | |||||||

| kl-2 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| kl-3 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| kl-5 | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| ORY | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| PRY | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| PPr-Y | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | 0 |

| CCY | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| ARY | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| WDY | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Pp1-Y1 | + | + | + | + | − | − | 0 | − | − |

| Pp1-Y2 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| FDY† | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

As described in ref.23 the Y chromosome became part of an autosome in the D. pseudoobscura lineage.

The FDY gene is a functional duplication to the Y of the autosomal gene CG11844, which happened within the D. melanogaster lineage, after the split from D. simulans (ref.21; A. B. Carvalho and A. G. Clark, in preparation).

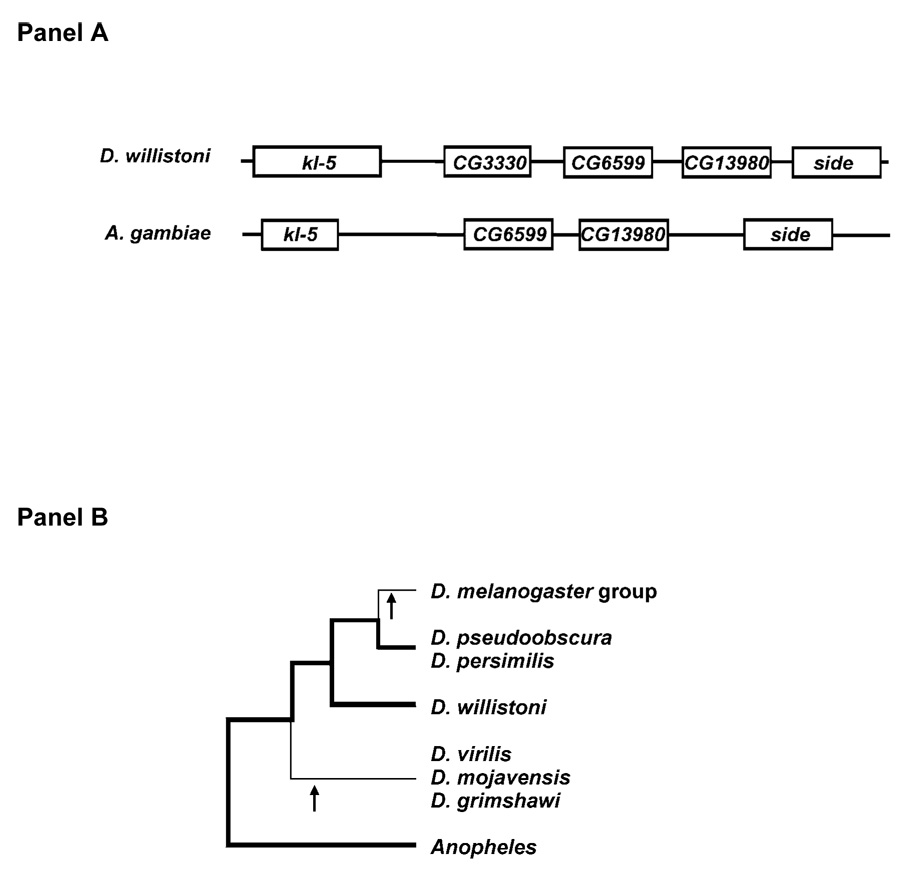

Figure 1. Synteny analysis of the kl-5 gene.

The gene is Y-linked in all examined Drosophila species except D. willistoni (and in D. pseudoobscura / D. persimilis), which might suggest a Y-to-autosome transfer in the D. willistoni lineage. However, the conserved synteny between D. willistoni and Anopheles gambiae (panel A) shows that the autosomal D. willistoni location is ancestral (thick lines in panel B). Hence, there were two independent transfers of kl-5 to the Y chromosome (arrows in panel B). Note that the Drosophila CG3330 gene has no ortholog in Anopheles. See Supplementary Fig. 4 for the remaining species.

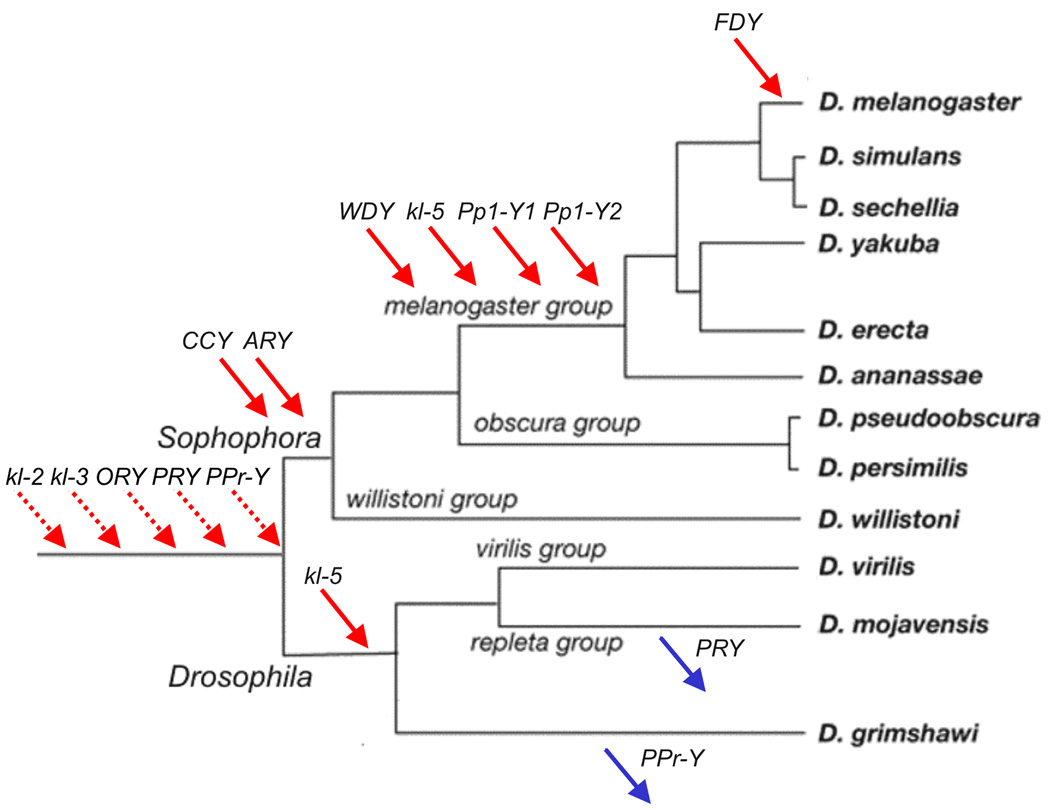

Figure 2. Gene movements in the Drosophila Y.

Gene gains (red arrows) and losses (blue arrows) were inferred by synteny. For changes that occurred before the split of the Drosophila and Sophophora subgenera (genes kl-2, kl-3, ORY, PRY, PPr-Y; dashed arrows) there is no close outgroup for inferring the direction (gain vs. loss) through synteny. However, all five genes are autosomal or X-linked in Anopheles, which suggests that they were acquired by the Y chromosome between 260 Myr (i.e., the Drosophila - Anopheles divergence time3,5 ) and 63 Myr ago.

It is clear from Fig. 2 that the gene content of the Drosophila Y chromosome is highly variable: among the 12 known Y-linked genes of D. melanogaster, only three (kl-2, kl-3, and ORY) are Y-linked in all sequenced species (we ignored the special case of the Y-autosome fusion in the D. pseudoobscura lineage because the changes that happened there were not caused by individual gene gain and loss). All other genes (75% of the total) moved onto or off the Y at least once, or were lost. This contrasts sharply with the remainder of the genome, where it was found that 514 genes out of ~ 13,000 (4% of the total ) moved to different chromosome arms in the same set of species6, and may suggest that there is increased gene movement to and from the Y, as has been observed for the X25–27. However, the rate of gene movements in the Y is smaller than the rate of similarly sized chromosome arms (Supplementary Discussion), and thus increased gene movement does not seem to be the major cause of the low conservation of Y-linked gene content.

The contrast between the Y and the other chromosomes seems to reflect their different evolutionary histories: whereas in the ancestor of all sequenced species the large chromosome arms had thousands of genes, the Y had a very low number of genes (we know five: kl-2, kl-3, PPr-Y, PRY, and ORY; Fig. 2) . This, coupled with a small number of gene movements in both genomic compartments would produce the present pattern of low conservation in the Y and high conservation in the other chromosomes. A possible caveat to this conclusion is that we do not know the full gene content of the Drosophila Y22. However, the low conservation of linkage we found should hold for the full gene set of the D. melanogaster Y, because the discovery of the 12 known Y-linked genes did not use any information from the other species (their genomic sequences were not even available at that time). Hence it is safe to conclude that the majority of the D. melanogaster Y-linked genes are recent acquisitions. In contrast, the mammalian Y mostly contains relic subsets of the X-linked genes, and variation in Y-linked gene content among species reflects differential loss of these relic genes and some gene acquisitions28,29. In Drosophila no such relic genes have been found, and variation arises mainly from an ongoing process of gene acquisition.

Figure 2 suggests that there are more gene gains than losses in the Y chromosome lineages examined, but these inferences were drawn using genes ascertained in D. melanogaster, opening a concern about bias. For example, it is likely that D. virilis harbors Y-linked genes that were either acquired after its ancestor split from the D. melanogaster lineage, or that were lost in the D. melanogaster lineage, and such genes would not be detected in the present study. Indeed, direct search in the D. virilis genome identified at least two Y-linked genes not shared with D. melanogaster (unpublished data). Given the ascertainment issue, only the rate of gene gain can be estimated in the D. melanogaster lineage branches of the phylogeny, and only the rate of gene loss can be estimated in the other branches (Supplementary Fig. 9). This procedure produces an estimate of the raw rate of gene gain by the Y of 0.1113 genes / Myr (7 gains in 63 Myr), while the raw rate of gene loss is 0.0073 genes / Myr (2 losses in 275 Myr). After correcting for an ascertainment bias in the loss rate (Supplementary Methods), and under the assumption that the rates of gene gain and gene loss are homogeneous across the lineages, we found that the rate of gene gain is 10.9 times higher than the rate of gene loss (P = 0.003 under the null hypothesis of equal gain and loss rates), which strongly suggests that the gene content of the Y has indeed increased.

In order to more fully explore the consequences of the ascertainment bias of gene content, we performed simulations of gene gain and loss employing the observed phylogeny and branch lengths, and made inferences of gene loss conditional on observing the same genes in D. melanogaster (identical to the true ascertainment). Approximate Bayesian estimates of the posterior densities of the rates of gene gain and loss were obtained by a rejection-sampling procedure for 1,000 runs (Supplementary Methods). All 1,000 runs had a gene gain rate exceeding the gene loss rate across the phylogeny (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 11). Thus both the simulations and the analytical result provide strong evidence that the Y chromosome lineages examined have experienced a net gain in gene number. The origin of the Drosophila Y remains a controversial issue9,23; if one assumes that it arose from the degeneration of the X, then only more recently had gene gains became important, after all its ancestral genes (shared with the X) had been lost.

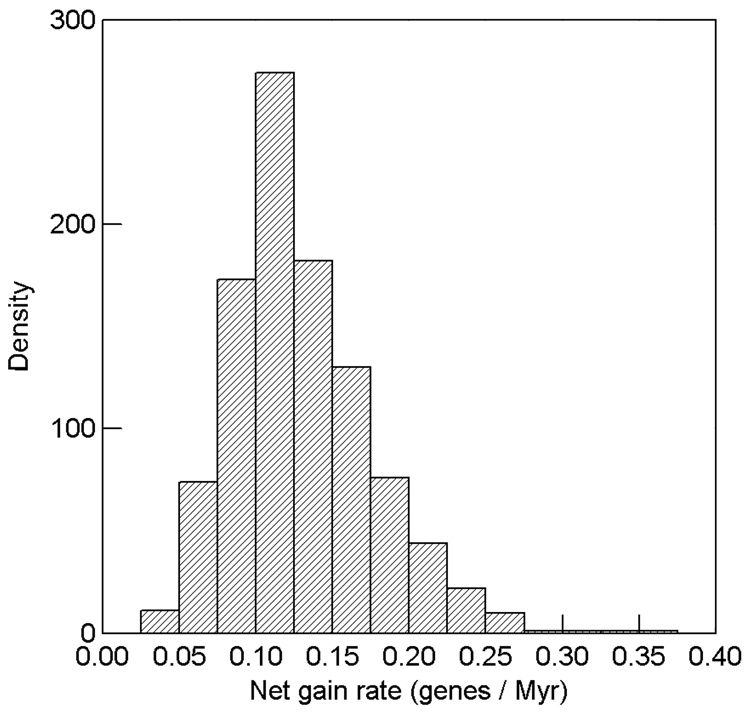

Figure 3. Posterior density of net rate of Y-linked gene gain in the Drosophila phylogeny.

A Bayesian rejection sampling procedure was applied (see text) to yield 1,000 estimates of rates of gene gain and loss conditional on the observed gains and losses of genes on the Y chromosome, and conditional on the genes being observed in D. melanogaster (matching the actual ascertainment of Y genes used in this study). The average of net gain rate (gain rate minus loss rate) is + 0.130 genes / Myr, and all 1,000 simulations had a higher rate of gene gain than loss (range of net gain rate: + 0.035 to + 0.352).

Given the restrictive characteristics of the Y chromosome (heterochromatic state, etc.) it is somewhat puzzling that genes moved there. Several hypotheses, ranging from neutrality to positive selection, could explain this, but our data do not allow definitive support for one model (Supplementary Discussion). The Y-linked gene Suppressor of Stellate, which is a recent acquisition in the D. melanogaster lineage, may be a case of positive selection30 (we excluded it because it is multi-copy and RNA-encoding). Whatever its cause, the finding that the Y chromosome has gained genes has interesting consequences. A chromosome that on average has gained genes and yet has few of them must be relatively young. Additional Diptera genome sequences may shed light in this issue. But the data in hand already strongly support the conclusion that the gene content of the Drosophila Y is younger than the other chromosomes, and that gene acquisition have had a prominent role in its evolution.

METHODS SUMMARY

Genomic sequences

We used the WGS3 assembly of D. melanogaster (accession AABU00000000), the TIGR assembly of D. pseudoobscura (accession AAFS01000000) and the CAF1 assemblies for all other species (available at http://rana.lbl.gov/drosophila/caf1.html). Full details of the strains used, sequencing and assembly strategies are described in reference24.

Search of orthologs of D. melanogaster Y-linked genes

We searched for these genes with TblastN20, using as queries the protein sequences of the D. melanogaster Y-linked genes18–22, and as databases the genomes of the remaining species. Orthology was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Supplementary Table 1 shows the accession numbers of the finished CDS sequences.

Molecular biology methods

DNA and RNA were extracted from the same strains used for the genome sequencing24. RNA and DNA extractions, PCR, and RT-PCR were performed using standard protocols19,20. 3′ RACE and 5′ RACE were performed with the Invitrogen Gene Racer™ Kit following the instructions of the manufacturer, using testis or whole body total RNA (in the case of D. grimshawi) as templates. DNA sequencing was done at Macrogen (Korea) and the Cornell DNA sequencing core facility.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Kumar, P. O'Grady, T. Markow, A.J. Bhutkar, S. C. Vaz, E. Betran, A. A. Peixoto, P. H. Krieger, P. Paiva, and four anonymous reviewers for comments in the manuscript and/or for sharing their unpublished results. We also thank T. Pinhao, A. Bastos and F. Krsticevic for help with the experiments, K. Krishnamoorthy for statistical advice and M. Fetchko for help with GenBank submission. Supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico-CNPq, Coordenacao de Aperfeicoamento do Pessoal de Ensino Superior-CAPES, FAPERJ, FIC-NIH grant TW007604-02 (A.B.C.), and NIH grant GM64590 (A.G.C.). Nucleotide sequence accession numbers are listed in the Supplementary Information.

References and Notes

- 1.Aparicio S, et al. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science. 2002;297:1301–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1072104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beverley SM, Wilson AC. Molecular evolution in Drosophila and the higher Diptera II. A time scale for fly evolution. J Mol Evol. 1984;21:1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02100622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zdobnov EM, et al. Comparative genome and proteome analysis of Anopheles gambiae and Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2002;298:149–159. doi: 10.1126/science.1077061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamura K, Subramanian S, Kumar S. Temporal patterns of fruit fly (Drosophila) evolution revealed by mutation clocks. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:36–44. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeates DK, Wiegmann BM. The Evolutionary Biology of Flies. New York: Columbia University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhutkar A, Russo SM, Smith TF, Gelbart WM. Genome-scale analysis of positionally relocated genes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1880–1887. doi: 10.1101/gr.7062307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nene V, et al. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316:1718–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice WR. Evolution of the Y sex chromosome in animals. BioScience. 1996;46:331–343. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2000;355:1563–1572. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachtrog D, Hom E, Wong KM, Maside X, de Jong P. Genomic degradation of a young Y chromosome in Drosophila miranda. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R30. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-r30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho AB, et al. Y chromosome and other heterochromatic sequences of the Drosophila melanogaster genome: how far can we go? Genetica. 2003;117:227–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1022900313650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoskins RA, et al. Sequence finishing and mapping of Drosophila melanogaster heterochromatin. Science. 2007;316:1625–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1139816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashburner M, Golic KG, Hawley RS. Drosophila : a Laboratory Handbook. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennison JA. The genetic and cytological organization of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaste. Genetics. 1981;98:529–548. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hackstein JH, Hochstenbach R. The elusive fertility genes of Drosophila: the ultimate haven for selfish genetic elements. Trends Genet. 1995;11:195–200. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skaletsky H, et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature. 2003;423:825–837. doi: 10.1038/nature01722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturtevant AH, Novitski E. The homologies of the chromosome elements in the genus Drosophila. Genetics. 1941;26:517–541. doi: 10.1093/genetics/26.5.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gepner J, Hays TS. A fertility region on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a dynein microtubule motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1993;90:11132–11136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho AB, Lazzaro BP, Clark AG. Y chromosomal fertility factors kl-2 and kl-3 of Drosophila melanogaster encode dynein heavy chain polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2000;97:13239–13244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230438397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carvalho AB, Dobo BA, Vibranovski MD, Clark AG. Identification of five new genes on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:13225–13230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231484998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho AB, Clark AG. Birth of a new gene on the Drosophila Y chromosome. Abstracts of the 44th Annual Drosophila Research Conference. 2003:113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vibranovski MD, Koerich LB, Carvalho AB. Two new Y-linked genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2008;179:2325–2327. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.086819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carvalho AB, Clark AG. Y chromosome of D. pseudoobscura is not homologous to the ancestral Drosophila Y. Science. 2005;307:108–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1101675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium, Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Betran E, Thornton K, Long M. Retroposed new genes out of the X in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2002;12:1854–1859. doi: 10.1101/gr.604902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerson JJ, Kaessmann H, Betran E, Long M. Extensive gene traffic on the mammalian X chromosome. Science. 2004;303:537–540. doi: 10.1126/science.1090042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturgill D, Zhang Y, Parisi M, Oliver B. Demasculinization of X chromosomes in the Drosophila genus. Nature. 2007;450:238–241. doi: 10.1038/nature06330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graves JA. Sex chromosome specialization and degeneration in mammals. Cell. 2006;124:901–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy WJ, et al. Novel gene acquisition on carnivore Y chromosomes. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e43. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurst LD. Is Stellate a relict meiotic driver? Genetics. 1992;130:229–230. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature