Abstract

The goal of the current study, conducted in freshly isolated thymocytes was (1) to investigate the possibility that the activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) in an intact cell can be regulated by protein kinase C (PKC) mediated phosphorylation and (2) to examine the consequence of this regulatory mechanism in the context of cell death induced by the genotoxic agent. In cells stimulated by the PKC activating phorbol esters, DNA breakage was unaffected, PARP-1 was phosphorylated, MNNG-induced PARP activation and cell necrosis were suppressed, with all these effects attenuated by the PKC inhibitors GF109203X or Gö6976. Inhibition of cellular PARP activity by PKC-mediated phosphorylation may provide a plausible mechanism for the previously observed cytoprotective effects of PKC activators.

Keywords: poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1, protein kinase C, necrosis, apoptosis, 1-methyl-3-nitro-1-nitrosoguanidine

Introduction

The nuclear enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1), a highly conserved constitutively-expressed 116 kDa protein is the most abundant isoform of the PARP enzyme family with roles in regulating multiple cellular functions in health and disease (overviewed in [1, 2]). Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation has been implicated in the regulation of multiple physiological cellular functions such as DNA repair, gene transcription, cell cycle progression, cell death, chromatin function and genomic stability [3]. Because PARP-1 becomes activated in response to DNA breaks, the nature of the various endogenous species capable of inducing DNA strand breaks (and thereby activating PARP1) in various disease conditions became of crucial interest. In addition to hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrite (a reactive nitrogen species formed from the diffusion-limited reaction of nitric oxide and superoxide anion) has been identified as a pathophysiologically relevant trigger of PARP activation [2].

From a pathophysiological standpoint, PARP activation can contribute to the development of disease via two main mechanisms: a) by driving the cell into an energetic deficit and a state of dysfunction and b) by catalyzing the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways. As far as the former pathway: PARP-1 functions as a DNA damage sensor and signaling molecule binding to both single- and double stranded DNA breaks. Upon binding to damaged DNA, PARP-1 forms homodimers and catalyzes the cleavage of NAD+ into nicotinamide and ADP-ribose to form long branches of (ADP-ribose)n polymers on target proteins including histones and PARP-1 itself. This process results in cellular energetic depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction and ultimately necrosis [1, 2]. As far as the latter pathway: numerous transcription factors, DNA replication factors and signaling molecules have also been shown to become poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated by PARP-1, but a PARP-mediated activation of the pluripotent transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) appears to be of crucial importance [1, 4]. Multiple lines of studies demonstrate that neutralization of peroxynitrite and/or pharmacological inhibition or genetic inactivation of PARP-1 is therapeutically effective in a wide range of cardiovascular, inflammatory, vascular and neurodegenerative diseases, both by protecting against cell death as well as by down-regulating multiple inflammatory pathways [1].

The activity of PARP-1 at the cellular level is primarily regulated by DNA single strand breaks. These breaks are recognized by zinc-fingers of PARP-1, and induce a conformational change in the enzyme, which, in turn, results in an increased catalysis of NAD+ to ADP-ribose units and nicotinamide, as the byproduct of the reaction [2]. However, a number of studies have also suggested alternative (i.e. non-DNA break dependent) intracellular regulatory mechanisms for PARP activity, with consequences for PARP-dependent cellular functional alterations. Some of these regulators (overviewed in [5]) include calcium, female sex hormones, xanthines and other factors. There are two published studies [6, 7] demonstrating the ability of protein kinase C (PKC) to phosphorylate PARP-1 in in vitro systems. The current study, conducted in freshly isolated thymocytes has investigated the possibility that the activation of PARP in an intact cell can be regulated by phosphorylation via PKC and examined the consequence of this regulatory mechanism in the context of cell death induced by nitrosative stress.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Propidium iodide (PI) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). All other chemicals, including MNNG were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The water soluble PARP inhibitor, PJ-34 [8] was produced by Inotek Pharmaceuticals (Beverly, MA, USA).

Cytotoxicity assay

Thymocytes were prepared according to [9, 10]. MNNG induced cytotoxicity was measured by propidium iodide (PI) uptake as described previously [9]. Cytotoxicity has also been determined by MTT assay, as described [11] with the exception that treatments were carried out in Eppendorf tubes and cells were spun down before removal of the medium and addition of DMSO.

PARP activity assay

PARP activity of cells was determined with the traditional PARP activity assay based on the incorporation of isotope from 3H-NAD+ into TCA (trichloroacetic acid)-precipitable proteins as described [10].

Caspase activity assay

Caspase-3 like activity was detected as described previously [12].

Single cell gel electrophoresis (comet-assay)

Single stranded DNA strand breaks were assayed by single cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay) according to [13] with modifications as described in [12].

Immunoprecipitation

PARP-1 phosphorylation was detected by immunoprecipitation. Cells were lysed with sample buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X 100, 50 mM Tris-Hcl (pH: 8,0), 1 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor cocktail (100x), 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO3), sonicated for 20 sec. Samples were precleared with 20 μl 50% sepharose-protein-A slurry for 1 h. Samples were incubated for 1,5 h with anti-PARP antibody (4 μg protein/500 μl sample). 50 μl 50% sepharose-protein-A slurry were added and incubated for 1h. Sepharose-protein-A microbeads were washed three times with sample buffer. Microbeads were mixed with SDS sample buffer then subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 8% gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes in 25mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.3, containing 192mM glycine, 0.02% (w/v) SDS, and 20% (v/v) methanol at 250mA for 90 min.

Western blotting and immunofluorescence

For Western blotting, cells were lysed with RIPA buffer, sonicated for 20 sec, and mixed with SDS sample buffer than subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 8% gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes in 25mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.3, containing 192 mM glycine, 0.02% (w/v) SDS, and 20% (v/v) methanol at 250mA for 90 min. immunostaining was performed using polyclonal anti-poly(ADP-ribose), anti-PARP-1 antibody, isoform specific anti-PKC and anti-phosphoserine antibodies according to standard procedures as described in [12, 14]. The same anti-PKC antibodies have been used for immunofluorescence stainings with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody according to standard procedures. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were aquired with a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal laser scanning microscope and z-stacked green and blue images were overlaid. Representative images are shown.

In vitro phosphorylation

Purified PARP-1 enzyme was phosphorylated by purified cPKC mixture (alpha, beta, gamma isoforms) in HEPES assay buffer (200 mM HEPES pH 7.5; 100 mM MgCl2 10 mM DTT). PKC was diluted in PKC storage buffer (20 mM HEPES pH7,5, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 25% glycerine, 0.02 % NaN3, 0.05 % Triton X-100) to a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml and was activated by the addition of 0.65 mM CaCl2 and phosphatidyl serine – diolein micellas. ATP mixture (5 μl) containing 0.988 mM ATP and 20-fold diluted 32P-ATP were added to the samples. Samples were incubated for 20, 50 and 90 minutes. Controls were prepared with the omission of PKC. Samples were mixed with SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 8% gels. Gels were dried. 32P signals were detected by autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were preformed three times on different days. Student’s t-test was applied for statistical analysis and for the determination of significance with p<0.05 considered as significant. For the statistical analysis of the comet assay experiments, Mann and Whitney’s U-test was applied.

Results

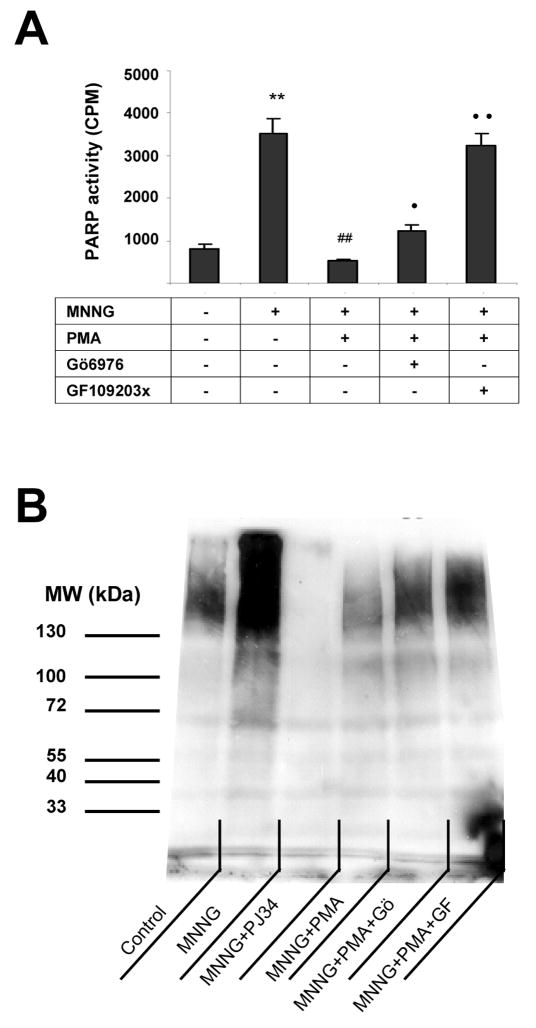

First, we have tested whether modulation of PKC activity affects PARP activation in thymocytes. Cells were treated with the prototypical DNA-damaging agent MNNG, which has the well-documented effect of inducing DNA single strand breakage, and subsequent PARP activation [12]. As expected, MNNG induced a marked degree of PARP activation (Fig. 1), which was suppressed by the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (Fig 1). When cells were pretreated for 30 min with the PKC activator phorbol ester PMA, a significant suppression of MNNG induced PARP activation was observed (Fig 1). The PARP-inhibitory effect of PMA was largely reversed by the compound bisindolylmaleimide (GF109203X), a broad spectrum PKC inhibitor and was partially attenuated by Gö6976 an inhibitor of conventional (calcium-dependent) PKC isoforms (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PKC activation suppresses MNNG-induced PARP activation.

Cells were treated with 20 μM MNNG for 10 min. Some samples were pretreated for 30 min with 100 nM PMA or with the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (3 μM). In some samples, PMA treatment was preceded with a 30 min treatment with the PKC inhibitors GF109203X and Gö6976. PARP activity of permeabilized cells was determined in 3H-NAD incorporation assay (A) and poly(ADP-ribose) of cell lysates was determined by Western blotting (B). (Mean±SEM of three independent experiments are presented. MNNG significantly (**p<0.01) increased PARP activity as compared to control. PMA significantly (##p<0.01) reduced MNNG-induced PARP activation. The effect of PMA was prevented by GF109203X (••p<0.01) and less effectively by Gö6976 (•p<0.01).

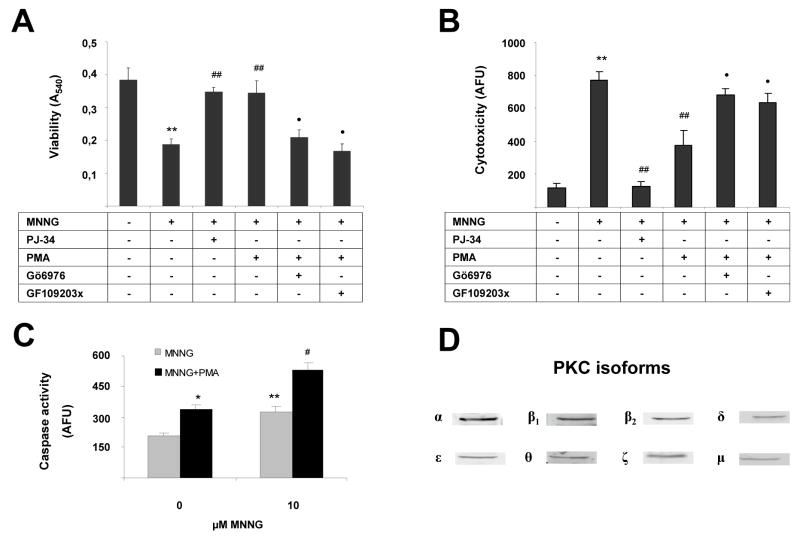

In order to investigate the consequences of PKC inhibition in the context of MNNG-induced cell death, we have measured the MNNG-induced changes in overall cell viability, necrotic cell death (propidium iodide uptake) and caspase activation, a measure of apoptotic cell death. As expected, MNNG significantly reduced cell viability and increased necrotic cell death as compared to control (Fig. 2). The cell death was dependent on PARP activation in this model, as evidenced by the inhibitory effect of the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (Fig. 2). Consistent with its PARP-inhibitory effect, PMA pretreatment attenuated MNNG-induced thymocyte cell necrosis (Fig 2a, 2b). As shown in previous experiments using PARP-dependent death of murine thymocytes, inhibition of cell necrosis by PARP inhibitors maintains cellular NAD+ and ATP levels and increases cellular energy charge [10, 15]. These effects are associated with an increase in the population of normal cells (not necrotic or apoptotic), with a decrease in the population of necrotic cells, as well as an increase in the population of apoptotic cells [10, 15]. The current results, showing an increase in caspase activation in MNNG-treated cells in the presence of PMA (Fig 2c) are consistent with a similar pattern of shift in cellular death pathways. The effect of PMA in attenuating cell necrosis was prevented by pretreatment of the cells with the PKC inhibitors GF109203X and by Gö6976 (Fig. 2a, 2b).

Fig. 2. PKC activation protects from MNNG-induced cytotoxicity.

Cells were treated with 10 (A) or 20 (B) μM MNNG for 10 min. Some samples were pretreated for 30 min with 100 nM PMA or with the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (3 μM). In some samples, PMA treatment was preceded with a 30 min treatment with the PKC inhibitors GF109203X and Gö6976. Viability was determined in MTT reduction test (A) and necrotic death was measured by propidium iodide uptake (B). Caspase activity, a measure of apoptotic death has been determined in a fluorimetric assay (C). PKC expression pattern of thymocytes has been determined by Western blotting (D). Data represent mean±SD of quadruplicate samples. Similar data were obtained in 3 independent experiments. MNNG significantly (**p<0.01) reduced cell viability and increased necrotic cell death as compared to control. PMA and PJ34 significantly (##p<0.01) inhibited the effect of MNNG. The effect of PMA was prevented by GF109203X (••p<0.01) and by Gö6976 (•p<0.01).

Next, the PKC expression pattern of the thymocytes was determined by Western blotting (Fig 2d). We have found evidence for all PKC isoforms in the cells (Fig 2d). (The full images of Western blots are shown on Figure S1.)

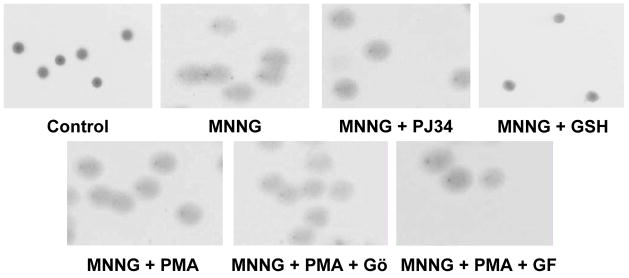

Because PKC can affect a wide variety of cell functions, we have designed a control experiment to test whether the degree of DNA strand breakage induced by MNNG can be affected by the PKC activator and inhibitor compounds used. The PKC activator PMA (in the absence or presence of the PKC inhibitors GF109203X and Gö6976) had no effect on the degree of DNA strand breakage induced by MNNG (Fig 3). The positive control glutathion (10 mM) abolished MNNG-induced DNA breakage. This finding is consistent with the view that it is not the initial trigger of PARP activation (i.e. DNA strand breakage), but some other downstream cellular pathway (such as PARP activity itself) is affected by the PKC modulators used in the current study.

Fig. 3. PKC has no effect on MNNG-induced DNA breakage.

Cells were treated with 20 μM MNNG for 10 min. Some samples were pretreated for 30 min with 100 nM PMA or the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (3 μM) or glutathione (10 mM). In some samples, PMA treatment was preceded with a 30 min treatment with the PKC inhibitors GF109203X and Gö6976. Cells were embedded in low melting point agarose and DNA breakage was evaluated in comet assay. Neither PJ34 nor PMA had any effect on MNNG-induced DNA breakage. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown.

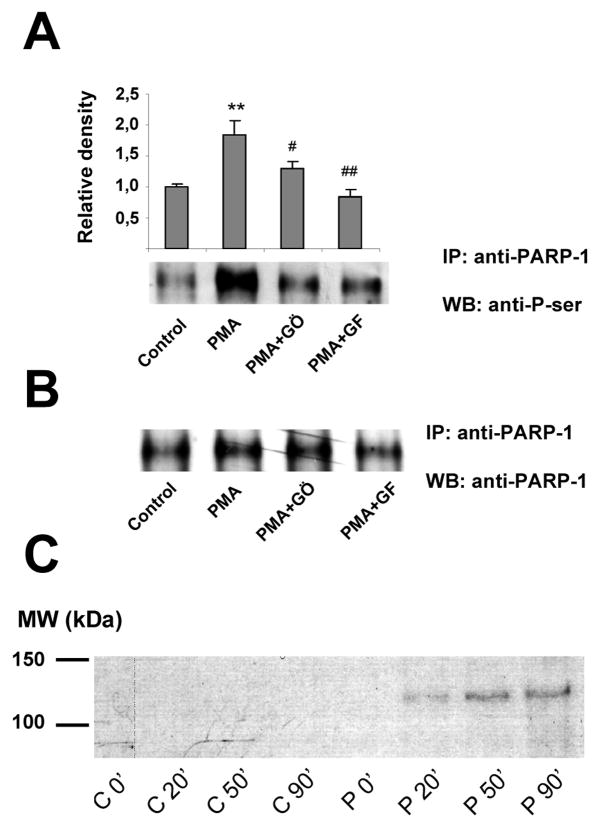

Finally, we have set out to determine whether the effects of PKC activator and the PKC inhibitors are associated with a direct phosphorylation of PARP1 in PMA-stimulated thymocytes. Phosphorylation of PARP1 was detected by two-way immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. As shown in Fig 4a, when PARP1 was immunoprecipitated and phosphorylation was detected by P-Ser antibody, PMA induced a significant phosphorylation of PARP, which was attenuated by both PKC inhibitors used. Similar results were observed in other series of experiments, when immunoprecipitation was carried out with P-Ser antibody and PARP1 was detected in Western blots (not shown). Purified PARP1 was also shown to be phosphorylated in vitro by PKC, as detected by autoradiography (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. PKC phosphorylates PARP-1 in PMA-stimulated thymocytes.

Thymocytes were pretreated with the PKC inhibitors GF109203X and Gö6976 for 30 min followed by a 30 min exposure to PMA. Phosphorylation of PARP1 was detected by two-way immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Part A: PARP1 was immunoprecipitated and phosphorylation was detected by P-Ser antibody. Part B. PARP1 was also detected for reference. Part C: Purified PARP1 was also phosphorylated in vitro by PKC as detected by autoradiography. In the control series (C0′–C90′) PKC was omitted from the reaction mixture whereas complete reaction mixtures (P0′–P90′) contained both PARP1 and PKC. Means±SEM or representative images from at least 3 independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

The current study was designed to examine whether PARP-1 may be a substrate of PKC in an intact cell system, and if so, whether this interaction can have functional consequences for the regulation of DNA damage-induced necrosis. PARP-1 has been reported to be substrate for kinases [16, 17] implicating the possibility of the regulation of PARP-1 activity by phosphorylation. PARP-1 is in close association with the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), which has been shown to phosphorylate PARP-1 [17]. Furthermore, purified PARP-1 has been reported to serve as a substrate for PKC, with a consequent inhibition of PARP’s DNA-binding capacity and catalytic activity [6, 7]. However, it has not been investigated in previous studies whether (a) PKC phosphorylates PARP in the intact cell (b) how this phosphorylation affects the activation of the enzyme within an intact cell and (c) whether the PKC-PARP interaction affects the course of cell death. The data shown in the current report confirm in a cell-based system that PARP-1 activity is inhibited by PKC activation. Furthermore, the current data with the PKC inhibitors suggest that - at least in part - conventional (calcium-dependent) PKC isoforms mediate the response. In addition, the current results demonstrate that the pattern of modulation of cell death responses by PKC activators and PKC inhibitors is consistent with their effects on PARP activation. In other words, inhibition of PARP activation by PMA mimics the effect of the ‘professional’ PARP inhibitor compounds (see [10, 15]) in preventing necrotic type cell death, while shifting the cell death pathways towards the apoptotic route (as evidenced by increased caspase activation in cells challenged with MNNG after pretreatment with PMA). Of note, when cell death or cell injury is stimulated by oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide) rather than MNNG, a similar cytoprotective effect of the PKC activating phorbol esters could be observed. Moreover, similar effects have been obtained with PMA stimulation in splenocytes representing a mature lymphoid population (Figure S2) but not in Jurkat T lymphoid cell line or adherent cell lines (A549 lung epithelial cells, HaCaT keratinocytes) (L.V. unpublished observation) indicating that our findings can be extended to more mature lympoid cells but not to transformed cell lines.

Indirect stimulation of the PKC signaling pathway e.g. in activated thymocytes or splenocytes may also lead to PARP inhibition as indicated by our finding that stimulation of cells for 24h but not for 1 or 6h caused an inhibition of MNNG-induced PARP activation (Figure S2). Moreover, immunofluorescent staining for conventional PKC isoforms revealed that PKC β1 but not other isoforms translocates into the nucleus at 24h following conA stimulation, whereas it localized to the cytoplasm at the earlier timepoints (Figure S2). These data raise the possibility that PKC β1 may mediate inhibition of PARP-1 in activated thymocytes and splenocytes.

Our findings, demonstrating that in a cell-based system PARP-1 is phosphorylated by PKC, and its activity is thereby reduced, and this reduction can confer cytoprotection can be viewed in the context of a multitude of published reports in the area of PKC, PARP-1 and cell death. For instance, it has been documented in multiple prior studies that cell death induced by various stimuli including oxidants or pro-inflammatory cytokines has been shown to be suppressed by PKC activating phorbol esters [18–22]. In addition, overexpression of PKC suppresses cell death [23]. Furthermore, during hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress, PKC becomes activated and inhibits cell death in vascular smooth muscle cells [24] and PKC inhibitors potentiate cell death in various systems [25–27]. PKC has also been shown to mediate resistance to myocardial infarction [28], a pathophysiological condition in which myocardial necrosis is mediated in part by PARP activation [29–31]. These lines of evidence point to an important role of PKC in regulation of different oxidant-induced cytotoxic processes. Based on the results of the current studies, we hypothesize that regulation of PARP-1 may be a pathway involved in some of the previously reported cell-death-modifying effects of PKC modulators. In addition to regulating cell death, the regulation of PARP-1 activity by PKC may also contribute to some of the signal transduction processes in the cell: Beckert and colleagues have presented such an example in human endothelial cells, where the IGF-1 induced VEGF expression appears to be dependent on a PKC-mediated inhibition of cellular PARP activity [32].

There are a number of observations in the current series of experiments that indicate that alternative or parallel pathways (other than the modulation of PARP by PKC) may also influence cell death. For instance, one can notice that while PARP phosphorylation induced by PMA was inhibited by both Gö6976 and by GF109203X (Fig 4), the inhibition of PARP activity by PMA was only partially reversed by Gö6976, while it was completely reversed in the case of GF109203X pretreatment (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, both PKC inhibitors prevented the protective effect of PMA against MNNG-induced cell death in the thymocytes to a comparable degree (Fig. 2). It is quite conceivable that complex interactions of a multitude of PARP-independent effects and interactions are involved in the modulation of cell death by PKC pathway modulators.

It may be interesting to note here that PKC has also been shown to activate PARP-1 in fibroblasts and human monocytes [33, 34]. Although several possible explanations (e.g. different cell types and conditions used in these studies) could be given for this seeming contradiction with our current data, we propose an alternative explanation. PMA may cause a low level of PARP-1 activation leading to PARP-1 automodification which is known to inhibit the activity of the enzyme. In PMA-pretreated cells, MNNG-induced massive DNA breakage can thus only trigger a weak PARP activation which is not sufficient to induce necrosis. Whether or not this may be the case requires further investigation.

It appears that the evidence for PKC regulating PARP-1 activity and PARP-dependent cellular events is solid and multiple. It is interesting to note that pathways that regulate towards the reverse direction (PARP activity affecting PKC activity) also exist. A physical association between PARP and PKC and regulation of PKC signaling by PARP may be indicated by the findings that PARP inhibition suppresses PKC activity [35, 36]. In addition, PARP modulates the properties of MARCKS proteins that are important substrates of PKC [36, 37]. In endothelial cells placed in elevated extracellular glucose, PKC activity is regulated by PARP via the mitochondrial oxidant generation/PARP activation/GAPDH inhibition connection [38].

In summary, the current study provides direct evidence for the regulation of cellular PARP-1 activity by PKC in intact thymocytes. In addition, the current study is the first to implicate the modulatory role of PKC activators and inhibitors in the process of MNNG-induced cell necrosis. Based on the data presented in the current report, we propose that PKC, (at least in part) via modulation of endogenous cellular PARP-1 activity, plays a significant role in modulating cell death in thymocytes. It will be interesting to study whether the modulation of PARP-1 by PKC is also relevant for other cell types and whether it also occurs in various disease conditions in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 PKC expression pattern of thymocytes. Full images of Western blots presented in truncated form in Figure 2d.

Figure S2 Thymocyte activation also inhibits PARP activation. PMA stimulation (30 min) of splenocytes inhibits MNNG-induced PARP activation similarly to that observed in thymocytes (A). Thymocytes and splenocytes were also treated for 1, 6 and 24h with conA followed by a 10 min exposure to 20 μM MNNG. 1h and 6h treatments with conA had no effects on PARP activation (not shown) but 24h after conA stimulation, MNNG-induced PARP activation was suppressed (B). PKC β1 translocates into the nucleus at 24h following conA stimulation as determined by immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. FITC staining (green) labels PKC β1 whereas DAPI stained nuclei (blue). Overlay of z-stack images shows nuclear translocation of PKC β1 at 24 but not at 6h (C).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Hungarian Ministry of Health (12/2006), the Hungarian National Science Research Fund (OTKA K60780) and from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 GM060915). ÉS and TB were supported by a Bolyai Fellowship from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. LV was supported by an István Széchenyi Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- MNNG

1-methyl-3-nitro-1-nitrosoguanidine

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PI

propidium iodide

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PKC

protein kinase C

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

CS is a founder, shareholder and consultant to Inotek Pharmaceuticals, a company involved in the development of PARP inhibitors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jagtap P, Szabo C. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and the therapeutic effects of its inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:421–440. doi: 10.1038/nrd1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virag L, Szabo C. The therapeutic potential of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:375–429. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. The diverse biological roles of mammalian PARPS, a small but powerful family of poly-ADP-ribose polymerases. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3046–82. doi: 10.2741/2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilar-Quesada R, Munoz-Gamez JA, Martin-Oliva D, Peralta-Leal A, Quiles-Perez R, Rodriguez-Vargas JM, de Almodovar MR, Conde C, Ruiz-Extremera A, Oliver FJ. Modulation of transcription by PARP-1: consequences in carcinogenesis and inflammation. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1179–1187. doi: 10.2174/092986707780597998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szabo C, Pacher P, Swanson RA. Novel modulators of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:626–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer PI, Farkas G, Buday L, Mikala G, Meszaros G, Kun E, Farago A. Inhibition of DNA binding by the phosphorylation of poly ADP-ribose polymerase protein catalysed by protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;187:730–736. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91256-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka Y, Koide SS, Yoshihara K, Kamiya T. Poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase is phosphorylated by protein kinase C in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;148:709–717. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90934-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagtap P, Soriano FG, Virag L, Liaudet L, Mabley J, Szabo E, Hasko G, Marton A, Lorigados CB, Gallyas F, Jr, Sumegi B, Hoyt DG, Baloglu E, VanDuzer J, Salzman AL, Southan GJ, Szabo C. Novel phenanthridinone inhibitors of poly (adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) synthetase: potent cytoprotective and antishock agents. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1071–1082. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai P, Bakondi E, Szabo E, Gergely P, Szabo C, Virag L. Partial protection by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors from nitroxyl-induced cytotoxity in thymocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1616–1623. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00756-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virag L, Scott GS, Cuzzocrea S, Marmer D, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Peroxynitrite-induced thymocyte apoptosis: the role of caspases and poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase (PARS) activation. Immunology. 1998;94:345–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virag L, Kerekgyarto C, Fachet J. A simple, rapid and sensitive fluorimetric assay for the measurement of cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00115-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai P, Hegedus C, Erdelyi K, Szabo E, Bakondi E, Gergely S, Szabo C, Virag L. Protein tyrosine nitration and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-treated thymocytes: implication for cytotoxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2007;170:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175:184–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griger Z, Payer E, Kovacs I, Toth BI, Kovacs L, Sipka S, Biro T. Protein kinase C-beta and -delta isoenzymes promote arachidonic acid production and proliferation of MonoMac-6 cells. J Mol Med. 2007;85:1031–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virag L, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase activation mediates mitochondrial injury during oxidant-induced cell death. J Immunol. 1998;161:3753–3759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ariumi Y, Masutani M, Copeland TD, Mimori T, Sugimura T, Shimotohno K, Ueda K, Hatanaka M, Noda M. Suppression of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity by DNA-dependent protein kinase in vitro. Oncogene. 1999;18:4616–4625. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruscetti T, Lehnert BE, Halbrook J, Le TH, Hoekstra MF, Chen DJ, Peterson SR. Stimulation of the DNA-dependent protein kinase by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14461–14467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byun HS, Park KA, Won M, Yang KJ, Shin S, Piao L, Kwak JY, Lee ZW, Park J, Seok JH, Liu ZG, Hur GM. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate protects against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced necrotic cell death by modulating the recruitment of TNF receptor 1-associated death domain and receptor-interacting protein into the TNF receptor 1 signaling complex: Implication for the regulatory role of protein kinase C. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1099–1108. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chihab R, Oillet J, Bossenmeyer C, Daval JL. Glutamate triggers cell death specifically in mature central neurons through a necrotic process. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;63:142–147. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1997.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CH, Han SI, Lee SY, Youk HS, Moon JY, Duong HQ, Park MJ, Joo YM, Park HG, Kim YJ, Yoo MA, Lim SC, Kang HS. Protein kinase C-ERK1/2 signal pathway switches glucose depletion-induced necrosis to apoptosis by regulating superoxide dismutases and suppressing reactive oxygen species production in A549 lung cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:371–385. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansat V, Laurent G, Levade T, Bettaieb A, Jaffrezou JP. The protein kinase C activators phorbol esters and phosphatidylserine inhibit neutral sphingomyelinase activation, ceramide generation, and apoptosis triggered by daunorubicin. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5300–5304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yiang GT, Yu YL, Hu SC, Chen MH, Wang JJ, Wei CW. PKC and MEK pathways inhibit caspase-9/-3-mediated cytotoxicity in differentiated cells. FEBS Lett. 2008 February 15; doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.018. e-pub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gubina E, Rinaudo MS, Szallasi Z, Blumberg PM, Mufson RA. Overexpression of protein kinase C isoform epsilon but not delta in human interleukin-3-dependent cells suppresses apoptosis and induces bcl-2 expression. Blood. 1998;91:823–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li PF, Maasch C, Haller H, Dietz R, von HR. Requirement for protein kinase C in reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1999;100:967–973. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drew L, Kumar R, Bandyopadhyay D, Gupta S. Inhibition of the protein kinase C pathway promotes anti-CD95-induced apoptosis in Jurkat T cells. Int Immunol. 1998;10:877–889. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.7.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi D, Watanabe N, Yamauchi N, Tsuji N, Sato T, Sasaki H, Okamoto T, Niitsu Y. Protein kinase C inhibitors augment tumor-necrosis-factor-induced apoptosis in normal human diploid cells. Chemotherapy. 1997;43:415–423. doi: 10.1159/000239600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L, Glazer RI. Induction of apoptosis in glioblastoma cells by inhibition of protein kinase C and its association with the rapid accumulation of p53 and induction of the insulin-like growth factor-1-binding protein-3. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1711–1719. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joyeux M, Baxter GF, Thomas DL, Ribuot C, Yellon DM. Protein kinase C is involved in resistance to myocardial infarction induced by heat stress. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:3311–3319. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thiemermann C, Bowes J, Myint FP, Vane JR. Inhibition of the activity of poly(ADP ribose) synthetase reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart and skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:679–683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zingarelli B, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Genetic disruption of poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibits the expression of P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 1998;83:85–94. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pacher P, Szabo C. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) in cardiovascular diseases: the therapeutic potential of PARP inhibitors. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2007;25:235–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2007.00018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckert S, Farrahi F, Perveen GQ, Aslam R, Scheuenstuhl H, Coerper S, Konigsrainer A, Hunt TK, Hussain MZ. IGF-I-induced VEGF expression in HUVEC involves phosphorylation and inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh N, Poirier G, Cerutti P. Tumor promoter phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate induces poly ADP-ribosylation in human monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;126:1208–1214. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh N, Poirier G, Cerutti P. Tumor promoter phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate induces poly(ADP)-ribosylation in fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1985;4:1491–1494. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ricciarelli R, Palomba L, Cantoni O, Azzi A. 3-Aminobenzamide inhibition of protein kinase C at a cellular level. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:465–467. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitz AA, Pleschke JM, Kleczkowska HE, Althaus FR, Vergeres G. Poly(ADP-ribose) modulates the properties of MARCKS proteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9520–9527. doi: 10.1021/bi973063b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao D, Severson DL, Zwiers H, Hollenberg MD. Radiolabelling of bovine myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS) in an ADP-ribosylation reaction. Biochem Cell Biol. 1994;72:391–396. doi: 10.1139/o94-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du X, Matsumura T, Edelstein D, Rossetti L, Zsengeller Z, Szabo C, Brownlee M. Inhibition of GAPDH activity by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activates three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1049–1057. doi: 10.1172/JCI18127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 PKC expression pattern of thymocytes. Full images of Western blots presented in truncated form in Figure 2d.

Figure S2 Thymocyte activation also inhibits PARP activation. PMA stimulation (30 min) of splenocytes inhibits MNNG-induced PARP activation similarly to that observed in thymocytes (A). Thymocytes and splenocytes were also treated for 1, 6 and 24h with conA followed by a 10 min exposure to 20 μM MNNG. 1h and 6h treatments with conA had no effects on PARP activation (not shown) but 24h after conA stimulation, MNNG-induced PARP activation was suppressed (B). PKC β1 translocates into the nucleus at 24h following conA stimulation as determined by immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. FITC staining (green) labels PKC β1 whereas DAPI stained nuclei (blue). Overlay of z-stack images shows nuclear translocation of PKC β1 at 24 but not at 6h (C).