Abstract

Reduction in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF)-mediated dilatory function in large, elastic arteries during hypertension is reversed after blood pressure normalization. We investigated whether similar mechanisms occurred in smaller mesenteric resistance arteries from aged Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats, spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), and SHRs treated with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, enalapril, using immunohistochemistry, serial-section electron microscopy, electrophysiology and wire myography. Unlike the superior mesenteric artery, EDHF relaxations in muscular mesenteric arteries were not reduced in SHRs, although morphological differences were found in the endothelium and smooth muscle. In WKY rats, SHRs and enalapril-treated SHRs, relaxations were mediated by small-, large-, and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, which were distributed in the endothelium, smooth muscle, and both layers, respectively. However, only WKY hyperpolarizations and relaxations were sensitive to gap junction blockers, and these arteries expressed more endothelial and myoendothelial gap junctions than arteries from SHRs. Responses in WKY rats, but not SHRs, were also reduced by inhibitors of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), 14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid (14,15-EEZE) and miconazole, although sensitivity to EET regioisomers was endothelium-independent in all rats. Enalapril treatment of SHRs reduced blood pressure and restored sensitivity to 14,15-EEZE, but not to gap junction blockers, and failed to reverse the morphological changes. In conclusion, the mechanisms underlying EDHF in muscular mesenteric arteries differ between WKY rats and SHRs, with gap junctions and EETs involved only in WKY rats. However, reduction of blood pressure in SHRs with enalapril restored a role for EETs, but not gap junctions, without reversing morphological changes, suggesting a differential control of chemical and structural alterations.

The endothelium of arteries plays a critical role in the regulation of vascular tone by activating vasodilator pathways, the principal mediators being nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF). The action of EDHF depends on hyperpolarization and relaxation of smooth muscle cells that is initiated in the endothelium, with a rise in intracellular calcium, activation of small-conductance (SKCa) and intermediate-conductance (IKCa) calcium-dependent potassium channels, and hyperpolarization of the endothelial membrane. Although the mechanism by which endothelial hyperpolarization is transduced to smooth muscle hyperpolarization is still controversial and may vary among different vascular beds and species, there is developing consensus that both contact-mediated and diffusible pathways exist (for review, see Triggle et al., 2003; Griffith et al., 2004; Sandow et al., 2004; Félétou and Vanhoutte, 2006).

For a contact-mediated mechanism to underlie EDHF, gap junctions must link the endothelium with the inner layer of smooth muscle. Indeed, a close correlation exists between the incidence of myoendothelial gap junctions (MEGJs) and EDHF in a number of arteries of different size and morphology (Sandow and Hill, 2000; Sandow et al., 2002, 2003, 2004), and EDHF is blocked in small mesenteric arteries after pinocytotic loading of endothelial cells with antibodies against connexin40, a component of MEGJs in this vessel (Mather et al., 2005). Further proof of the involvement of MEGJs in the action of EDHF has emerged through the use of gap junction uncouplers (Griffith et al., 2004). Although many such antagonists have been discredited (Chaytor et al., 1997; Tare et al., 2002), the gap peptides that mimic extracellular connexin sequences are reported to act in a gap junction-specific manner (Matchkov et al., 2006). With regard to diffusible elements, endothelial release of the arachidonate metabolites, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), represents a viable mechanism by which a transferable factor could elicit a smooth muscle hyperpolarization and relaxation, through the opening of BKCa channels, perhaps via activation of transient receptor potential channels (Loot et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009).

In hypertension, endothelial dysfunction occurs through deficits in both nitric oxide and EDHF (Goto et al., 2004b; Yang and Kaye, 2006). In the large, elastic, superior mesenteric artery of aged spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), which represent a model of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, EDHF-mediated hyperpolarization and relaxation are severely attenuated but completely restored and even augmented after inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system (Goto et al., 2000, 2004a). Therefore, our aim was to determine whether similar changes in EDHF were found in the smaller resistance vessels of the mesenteric circulation and whether they were accompanied by alterations to myoendothelial coupling and the involvement of gap junctional mechanisms. Because our previous studies demonstrated no change in the incidence of MEGJs in the caudal artery of SHRs, where there was no deficit of EDHF (Sandow et al., 2003), we hypothesized that any reduction in EDHF-mediated dilation would be accompanied by diminished myoendothelial coupling and that antihypertensive treatment would improve dilation and be accompanied by a greater prominence of MEGJs and gap junction-dependent mechanisms. However, in contrast to the superior mesenteric artery, our data did not demonstrate any differences in the sensitivity of EDHF-mediated dilatory responses among muscular mesenteric arteries taken from aged WKY rats, SHRs, or enalapril-treated SHRs, but we did uncover differences in the expression of endothelial and myoendothelial gap junctions and alterations in the involvement of gap junctions and eicosanoids in the mechanisms recruited by the different rat groups to elicit EDHF dilation.

Materials and Methods

Experiments involved 11- to 12-month-old male WKY rats and age-matched SHRs and were conducted under a protocol approved by the Animal Experimentation and Ethics Committee of the Australian National University (Canberra, ACT, Australia). Some groups of 9- to 10-month-old SHRs were treated for 8 weeks with enalapril (35 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) as used previously (Goto et al., 2000). Blood pressure measurements were taken in conscious animals using tail cuff plethysmography, with the average of four readings taken as the representative systolic blood pressure for a given rat.

Electrophysiology and Myography. Rats were anesthetized with ether and decapitated, and the primary mesenteric or first-order arteries, originating from the superior mesenteric artery and supplying the ileum, were removed and cut into short segments for either intracellular electrophysiological recordings or isometric tension studies. All experiments were conducted in the presence of Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (100 μM) and indomethacin (10 μM) to eliminate the contribution of nitric oxide and prostanoids, respectively. In some experiments, ODQ (10 μM) was present with other drugs to ensure complete blockade of nitric oxide, although preliminary experiments showed that ODQ did not produce any additional inhibitory effects to those of Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester.

For electrophysiological studies, segments (10 mm) were pinned in a recording chamber and superfused with Krebs' solution containing 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 11 mM glucose, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and maintained at 33 to 34°C. Intracellular recordings of membrane potential were made with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) by using sharp microelectrodes (120–180 MΩ) filled with propidium iodide (0.2% in 0.5 M KCl) advanced from the adventitial surface of the arterial segments. All intracellular recordings were made from smooth muscle cells identified by dye labeling. Hyperpolarization to acetylcholine (ACh) (1 μM) was measured in the presence or absence of phenylephrine (1 μM) by using preparations taken from different rats. Additional preparations were used to measure responses to ACh before and after incubation in the EET analog 14,15-EEZE (10 μM) for 15 min or a combination of the connexin mimetic peptides, 37,43gap 27, 40gap 27, and 43gap 26 (100 μM each) for 1 h. Hyperpolarizations to the ATP-dependent potassium channel (KATP) opener, levcromakalim (10 μM), and the IKCa opener, 1-EBIO (300 μM), were also recorded.

For isometric tension studies, segments (1 mm) were mounted on tungsten wires (40 μm) in a wire myograph (model 510A; DMT A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) and stretched to the equivalent of 80 mm Hg during normalization. Vessels were equilibrated for 30 min and then preconstricted with concentrations of phenylephrine (0.3–1 μM), which produced submaximal constrictions of 70 to 80% of the maximal constriction obtained in each vessel. Responses to the cumulative addition of ACh (0.001–3 μM) were investigated in the absence and presence of the connexin mimetic peptide combination of 37,43gap 27, 40gap 27, and 43gap 26 (100 μM each), KCa channel inhibitors iberiotoxin (IbTx; 100 nM), apamin (500 nM), and TRAM-34 (500 nM; kindly supplied by Dr. H. Wulff); catalase (2000 U/ml), the EET analog 14,15-EEZE (10 μM), and the cytochrome P450 epoxygenase inhibitor miconazole (1 μM). Gap peptides were preincubated for 1 h, and TRAM-34 was incubated for 30 min, whereas all other drugs were preincubated for 10 to 15 min.

The dose-dependent dilatory effects of the regioisomer epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, 5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET (0.01–10 μM; synthesized by the laboratory of J. R. Falck), and of the potassium channel openers, levcromakalim and 1-EBIO, were also recorded among the rat groups. The effects of EEZE (10 μM), miconazole (1 μM) and the KATP inhibitor glibenclamide (10 μM) on dilations to ACh and levcromakalim were determined to rule out the involvement of KATP channels in the actions of EEZE and miconazole.

In some preparations, the endothelium was removed by gently rubbing a small feather through the lumen. Successful removal of endothelium was confirmed by the failure of 1 μM ACh to induce dilation.

Immunohistochemistry. Rats were anesthetized as above, perfused with saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% NaNO3, 5 U/ml heparin (at 60 mm Hg), and arteries were removed, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA), and 10-μm sections cut on a cryostat. Alternatively, the rats were additionally perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde (0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer), and their arteries removed and processed as whole mounts (Grayson et al., 2004; Rummery et al., 2005). The following antibodies were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% Triton X-100: rabbit anti-SKCa (1:200, APC-025, Batch AN-03; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel); rabbit anti-IKCa (1:100, APC-064; Alomone Labs); rabbit anti-IKCa (1:100, kindly supplied by C.B. Neylon; see Neylon et al., 2004, for antibody characterization); rabbit anti-BKCa (1:50, APC-021; Alomone Labs); rabbit anti-IP3 receptor subtypes I (1:50), II (1:10) (Wojcikiewicz, 1995); mouse anti-IP3 receptor subtype III (1: 50; BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); sheep anti-connexin37 (Cx37, 1:100; Grayson et al., 2004; Rummery et al., 2005); sheep anti-Cx40 (1:100; Grayson et al., 2004; Rummery et al., 2005); and rabbit anti-Cx43 (1:100; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA). Staining was visualized using Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, donkey anti-mouse, or donkey anti-goat antibodies (1:100, 1:100, 1:300, respectively; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA), and image series were collected at 0.3 μm with a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Specificity of antibodies was tested by omission of the primary antibody or preincubation of the primary antibody, with a 10-fold excess of the immunogenic peptide for 1 h at room temperature before application to the tissue.

Quantification of the number of holes in the internal elastic lamina (IEL) was made possible in whole-mount preparations because of autofluorescence with 488-nm excitation. Because staining for IKCa channels has been shown to be localized within holes in the IEL at the site of MEGJs (Sandow et al., 2006), antibodies against IKCa channels were used to localize myoendothelial projections. Whole-mount preparations were also stained with antibodies against the IP3 receptor subtypes I to III because the IP3 pathway is integral to the actions of ACh (Goto et al., 2007), and recent studies have implicated these stores in myoendothelial signaling (Isakson et al., 2007). To determine the incidence of expression of IKCa channels or IP3 receptors on myoendothelial projections within the IEL of whole-mount preparations, optical confocal series were taken of both immunohistochemical staining and the IEL from the level of the endothelium through to the inner surface of the smooth muscle. Sections containing the IEL were projected to a single image and recombined with single confocal images taken above the level of the IEL, close to the smooth muscle (Fig. 7A, see dotted line marked A and B). Counts of the number of holes in the IEL containing punctate staining were made from these images. The position of the puncta in the single confocal image, above the level of the endothelial cell layer, was verified by following each dot through the confocal z-stack to confirm its position relative to the cellular endothelial staining.

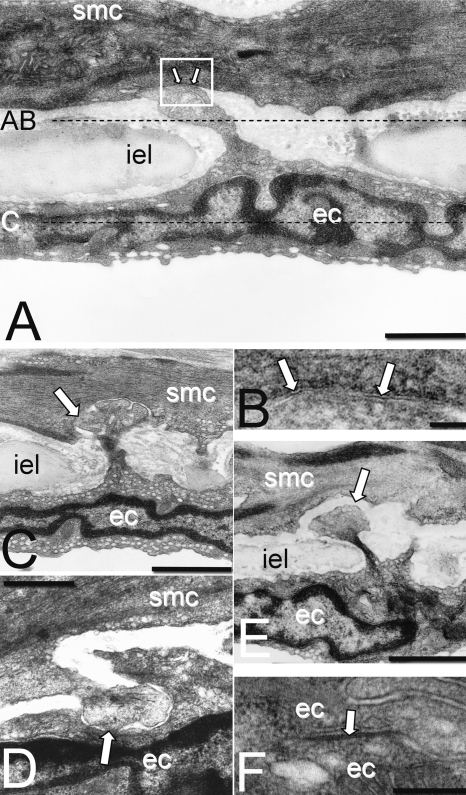

Fig. 7.

A, typical MEGJ formed at the end of an endothelial cell (ec) projection through the internal elastic lamina (iel). Dotted lines represent the focal planes of optical confocal sections shown in A to C of Fig. 8. B, pentalaminar membrane at point of contact between endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell (smc) in A (arrows, box). C and D, possible MEGJs at which there is no detectable gap between smooth muscle and endothelial membranes (arrows). E, endothelial projection with gap between the cell membranes would not be counted as a MEGJ. F, endothelial gap junction with pentalaminar membrane (arrow). Calibration bars, 800 nm in A; 50 nm in B; 1.5 μm in C and E; 700 nm in D; and 150 nm in F.

Quantification of Cx staining in the endothelium was undertaken using confocal image series taken through the endothelium of whole-mount preparations, which were subsequently projected to a single image and analyzed using ImageJ (National Center for Biotechnology Information). Three separate image fields were analyzed from each preparation. Preparations were made from three to four rats representing each of the three rat groups. Endothelial cell sizes were measured after staining with anti-Cx40, which highlights cellular perimeters (Grayson et al., 2004; Rummery et al., 2005).

Electron Microscopy. Rats were anesthetized with 44 and 8 mg/kg i.p. ketamine and xylazine, respectively, and processed as described previously (Sandow and Hill, 2000). Serial sections covering 5 μm of each vessel were examined along the IEL to locate MEGJs that were identified by the presence of pentalaminar membrane. Potential MEGJs, where there was no detectable gap between smooth muscle and endothelial membranes but pentalaminar membrane was not discernible, were also counted. The number of smooth muscle cell layers was determined by averaging four measurements 90° apart for each vessel.

Statistical Analysis. Statistical significance was tested using one- or two-way ANOVA, followed by unpaired Student's t tests, with Bonferroni modification for multiple groups as appropriate. Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. Numbers represent preparations, each taken from a different rat. A P value < 0.05 was taken to denote significance.

Results

Blood pressure of SHRs was significantly higher than that of WKY rats (SHRs, 196 ± 3 mm Hg, n = 16; WKY rats, 137 ± 4 mm Hg, n = 11; P < 0.05). Treatment of SHRs with enalapril successfully reduced blood pressure (117 ± 3 mm Hg, n = 21; P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Blood pressure of enalapril-treated SHRs was significantly lower than that of WKY rats.

Role of KCa Channels in EDHF Responses. Maximal constrictions to phenylephrine (0.1–10 μM) were significantly greater in SHRs than in enalapril-treated counterparts and WKY rats, although the sensitivity did not differ between the different rat groups (maximal constrictions and pD2 values, respectively; WKY rats, 8.3 ± 2.1 mN, -6.3 ± 0.2; SHRs, 19.7 ± 1.8 mN, -6.1 ± 0.1; SHR + enalapril, 11.3 ± 1.4 mN, -6.1 ± 0.1; n = 4–12). ACh (0.001–3 μM) reversed the constriction produced by submaximal concentrations of phenylephrine (0.3–1 μM) in all three rat groups without significant difference in pD2 values or peak amplitude of relaxation (maximum), respectively, among the groups (WKY rats, -7.9 ± 0.1, 97.8 ± 0.5%, n = 34; SHRs, -7.8 ± 0.1, 97.3 ± 0.7%, n = 24; SHR + enalapril, -7.8 ± 0.1, 97.7 ± 1.0%, n = 18). To determine whether differences existed in the time course of dilation among the groups, the sustained response that persisted after the initial peak response was also analyzed. No significant difference was found in pD2 values or peak amplitude of relaxation of the sustained response among the groups (WKY rats, -7.7 ± 0.1, 97.9 ± 1.8%, n = 25; SHRs, -7.8 ± 0.1, 98.4 ± 2.1%, n = 21; SHR + enalapril, -7.7 ± 0.1, 98.7 ± 2.6%, n = 18).

In the absence or presence of phenylephrine (1 μM), the resting membrane potential of smooth muscle cells was not significantly different among the three rat groups, phenylephrine producing approximately 10-mV depolarization (Table 1). ACh (1 μM) induced a hyperpolarization in all three groups. The amplitude of hyperpolarization in SHRs was significantly smaller than in WKY rats but was restored in enalapril-treated SHRs to values comparable with those in WKY rats (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Resting membrane potential measurements (RMP) in control and in ACh in the presence and absence of phenylephrine

| WKY | SHR | SHR + Enalapril | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without phenylephrine | |||

| RMP | –52 ± 0.4 mV (8) | –49 ± 0.9 mV (10) | –51 ± 0.9 mV (10) |

| RMP in ACh (1 μM) | –72 ± 1.0 mV (7) | –62 ± 1.6 mV (6)* | –69 ± 1.3 mV (6) |

| With phenylephrine (1 μM) | |||

| RMP | –39 ± 0.9 mV (8) | –40 ± 0.7 mV (8) | –41 ± 0.7 mV (7) |

| RMP in ACh (1 μM) | –69 ± 1.3 mV (6) | –60 ± 1.5 mV (6)* | –70 ± 1.7 mV (5) |

P < 0.05, when compared with WKY or SHR-enalapril, one-way ANOVA; mean ± S.E.M. Numbers in parentheses represent number of rats

Both levcromakalim (KATP opener) and 1-EBIO (IKCa channel opener) caused concentration-dependent hyperpolarizations and relaxations that did not differ between WKY rats and SHRs (pD2 values for relaxations to levcromakalim: WKY rats, -6.8 ± 0.2, n = 4; SHRs, -6.8 ± 0.2, n = 4; hyperpolarizations to 10 μM: WKY rats, -27 ± 1.5 mV, n = 4; SHRs, -27 ± 1.4 mV, n = 4; pD2 values for relaxations to 1-EBIO: WKY rats, -4.2 ± 0.1, n = 4; SHRs, -4.4 ± 0.2, n = 4; hyperpolarizations to 300 μM: WKY rats, -19 ± 0.9 mV, n = 3; SHRs, -18 ± 3.5 mV, n = 3), indicating no impairment in the ability of either smooth muscle or endothelial K channels, respectively, to elicit hyperpolarization and relaxation.

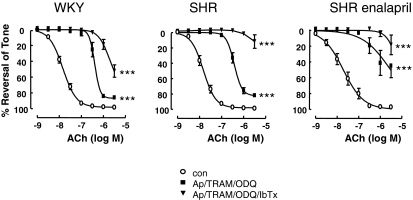

Blockers of calcium-activated potassium channels, namely the SKCa (apamin, 500 nM) and IKCa (TRAM-34, 500 nM) in the presence of 10 μM ODQ, significantly shifted ACh curves to the right in all three rat groups. Addition of the large-conductance KCa blocker IbTx (100 nM) abolished relaxations, although a small residual relaxation persisted in the WKY group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Role of calcium activated potassium channels in EDHF responses. ACh-induced dilations in mesenteric artery from WKY rats, SHRs, and enalapril-treated SHRs were significantly attenuated by apamin (500 nM), TRAM-34 (500 nM), ODQ (10 μM), and iberiotoxin (500 nM). Data are expressed as percentage reversal of a submaximal phenylephrine-induced tone (0.3–1 μM). Points represent means ± S.E.M. ***, P < 0.001, compared with respective controls, two-way ANOVA.

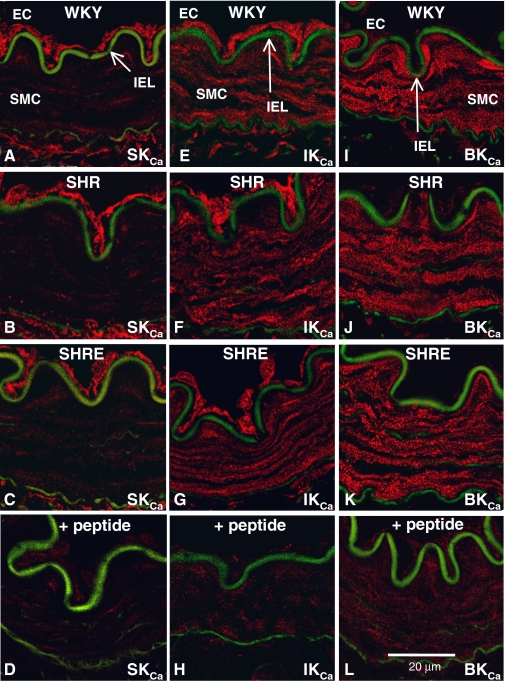

Immunohistochemical staining for SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa channels demonstrated that the channels were differentially distributed between the endothelium and smooth muscle; however, there was no difference in expression among the rat groups. Thus, SKCa expression was confined to the endothelium (Fig. 2, A–C), BKCa expression was confined to the smooth muscle (Fig. 2, I–K), and IKCa staining was found in both layers, although expression was stronger in the endothelium (Fig. 2, E–G). Specificity of the staining for each antibody was confirmed by absence after incubation with the antigenic peptide (Fig. 2, D, H, and L).

Fig. 2.

Calcium-dependent potassium channel expression in mesenteric arteries from WKY rats, SHRs, and enalapril-treated SHRs. A to C, SKCa expression was confined to the endothelium in WKY rats (A), SHRs (B), and enalapril-treated SHRs (C). E to G, IKCa expression was found in both endothelium and smooth muscle of WKY rats (E), SHRs (F), and enalapril-treated SHRs (G). I to K, BKCa expression was confined to the smooth muscle of WKY rats (I), SHRs (J), and enalapril-treated SHRs (K). Staining for each antibody was eliminated by preincubation with the immunizing peptide (D, SKCa;H,IKCa;L,BKCa).

Role of Gap Junctions in EDHF Responses. A combination of the gap mimetic peptides (37,43gap27, 40gap27, and 43gap26, 100 μM each) was used as a pharmacological means of assessing the role of gap junctions in ACh-induced relaxations. In WKY rats, gap peptides caused a significant rightward shift of the ACh curve, which was not shifted any further by IbTx (Fig. 3). In untreated and enalapril-treated SHRs, the gap peptides had no effect on responses, although the addition of IbTx produced a large significant rightward shift of responses in untreated SHRs and a smaller significant shift in enalapril-treated rats (Fig. 3). In WKY rats, IbTx administered without gap peptides also produced a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve to ACh (pD2, -7.5 ± 0.1, n = 4).

Fig. 3.

Effect of gap mimetic peptides (37,43gap 27, 40gap 27, 43gap 26; GP; 100 μM each) and IbTx (100 nM) on EDHF responses. Gap peptides attenuated ACh-induced dilations only in arteries from WKY rats (P < 0.001, compared with control, n = 7). IbTx substantially reduced dilations in SHRs (P < 0.001, n = 7) but less so in enalapril-treated SHRs (P < 0.05, n = 5). Data are expressed as percentage of reversal of a submaximal phenylephrine-induced tone (0.3–1 μM). Points represent means ± S.E.M.

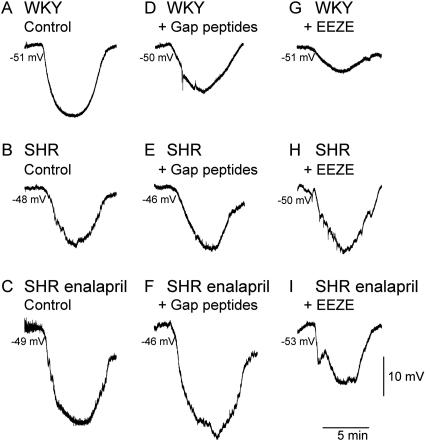

Resting membrane potentials did not vary significantly in the gap peptides in any of the rat groups (Table 2, gap peptides). However, the hyperpolarization elicited by ACh (0.1 μM) was significantly attenuated by the gap peptides in WKY rats but not in SHRs or SHR + enalapril (Table 2; Fig. 4, A–F). This concentration of ACh was chosen because it produced a response that was just maximal in all three rat groups (see Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Resting membrane potential measurements (RMP) in control and in ACh in the presence and absence of antagonists against EETs (EEZE) and gap junctions (gap peptides) Mean ± S.E.M. Numbers in parentheses represent number of rats.

| WKY | SHR | SHR + Enalapril | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | |||

| Control | |||

| RMP | —50 ± 0.4 (11) | —48 ± 0.5 (5) | —50 ± 1.1 (4) |

| RMP in ACh (0.1 μM) | —71 ± 0.6 (11) | —63 ± 2.1 (5)* | —72 ± 1.7 (4) |

| Gap peptides | |||

| RMP | —50 ± 1.7 (4) | —48 ± 0.9 (4) | —49 ± 1.5 (3) |

| RMP in ACh (0.1 μM) | —64 ± 1.5 (4)† | —64 ± 0.6 (3) | —69 ± 0.3 (3) |

| EEZE | |||

| RMP | —49 ± 1.2 (5) | —51 ± 1.4 (4) | —50 ± 1.4 (4) |

| RMP in ACh (0.1 μM) | —63 ± 2.4 (4)† | —68 ± 3.9 (3) | —65 ± 2.2 (4)† |

P < 0.05, when compared with WKY or SHR-enalapril, one-way ANOVA

P < 0.05, when compared with control of the same rat group, one-way ANOVA

Fig. 4.

Effect of gap peptides and EEZE on hyperpolarizations to ACh. Hyperpolarization induced by ACh (0.1 μM) under control conditions in mesenteric arterial segments taken from WKY rats (A), SHRs (B), and enalapril-treated SHRs (C) and after incubation in gap mimetic peptides (37,43gap 27, 40gap 27, 43gap 26; 100 μM each) in WKY rats (D), SHRs (E), and enalapril-treated SHRs (F). Effects of incubation in EEZE (10 μM) on responses in WKY rats, SHRs, and enalapril-treated SHRs are shown in G to I, respectively. Note the decreased amplitude of responses in D, G, and I compared with the control response in the same rat group.

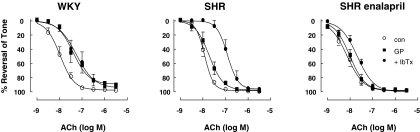

Role of EETs in EDHF Responses. Because of the involvement of BKCa channels in EDHF-mediated dilation in all three rat groups (Fig. 1), the contribution of EETs was assessed using 14,15-EEZE (10 μM) (Larsen et al., 2008) and miconazole (1 μM). ACh responses were significantly shifted to the right in WKY rats and enalapril-treated SHRs but were not affected in SHRs, an effect that was also paralleled by miconazole (Table 3). IbTx had no additional inhibitory effect on responses beyond that seen with EEZE in the two affected groups but did produce a significant shift in untreated SHRs (Table 3). In contrast, the addition of the gap peptide combination failed to produce a further significant rightward shift in any of the rat groups (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Role of EETs on EDHF-mediated relaxation The effects of the EETs antagonist EEZE (10 μM), the BKCa channel inhibitor IbTx (100 nM), and the cytochrome P450 inhibitor miconazole (1 μM) were tested on ACh-induced relaxations of mesenteric arteries taken from WKY rats, SHRs, and enalapril-treated SHRs. Data are summarized as pD2 values.

| WKY | SHR | SHR + Enalapril | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | —8.0 ± 0.1 (11) | —7.9 ± 0.1 (9) | —7.9 ± 0.2 (8) |

| EEZE | —7.4 ± 0.1 (5)* | —8.0 ± 0.1 (5) | —7.2 ± 0.2 (4)* |

| EEZE/IbTx | —7.3 ± 0.2 (5)* | —7.2 ± 0.1 (5)* | —7.1 ± 0.2 (4)* |

| EEZE/IbTx/gap | —7.1 ± 0.1 (5)* | —7.4 ± 0.2 (5) | —7.1 ± 0.1 (4)* |

| mimetic | |||

| peptide | |||

| Miconazole | —7.3 ± 0.1 (4)* | —7.7 ± 0.3 (4) | —7.2 ± 0.1 (3)* |

P < 0.05, when compared with control of the same rat group, one-way ANOVA. Numbers in parentheses represent number of rats

To rule out the involvement of KATP channels in the actions of miconazole (1 μM) and 14,15-EEZE (10 μM), we tested these compounds on relaxations to levcromakalim in WKY rats and found no significant reduction because of either of the compounds (P > 0.05, n = 4). Glibenclamide also had no significant effect on EDHF dilatations to ACh (P > 0.05, n = 4), confirming the lack of involvement of KATP channels.

The contribution of EETs to ACh-induced hyperpolarization was assessed using 14,15-EEZE (10 μM), which had no significant effect on resting membrane potential in any of the rat groups (Table 2). In contrast to the gap peptides, the hyperpolarization elicited by ACh was attenuated by EEZE in WKY rats and enalapril-treated SHRs, but not in SHRs (Table 2; Fig. 4, G–I).

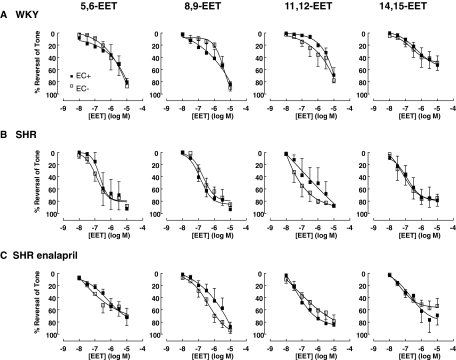

To determine whether the reactivity to EETs varied among the rat groups, we tested the dilatory effects of the four EET regioisomers (5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET, and 14,15-EET; 0.01–10 μM) in endothelium-intact and denuded arteries. We found no significant difference in responsiveness to the EET isomers between endothelium-intact and denuded arteries in any of the rat groups (Fig. 5). In addition, there was no significant difference in sensitivity to a particular EET isomer among the rat groups, nor any elevated sensitivity to a particular isomer within a rat group.

Fig. 5.

Dilations to EET regioisomers in endothelium-intact and denuded mesenteric arteries from WKY rats (n = 4), SHRs (n = 4), and enalapril-treated SHRs (n = 4). All rat groups dilated to EETs with no significant difference between endothelium-intact and denuded arteries. Data expressed as percentage reversal of a submaximal phenylephrine-induced tone (0.3–1 μM). Points represent means ± S.E.M.

Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in EDHF Responses. Because hydrogen peroxide has been described as an EDHF that could activate BKCa channels (Barlow and White, 1998), we incubated arterial segments in catalase (2000 U/ml) to investigate the non-EET-mediated activation of BKCa in SHRs. However, we found no significant effect on relaxations to ACh in SHRs or in WKY rats (pD2 values in catalase; WKY rats, -7.9 ± 0.1, n = 4; SHRs, -7.9 ± 0.4, n = 4).

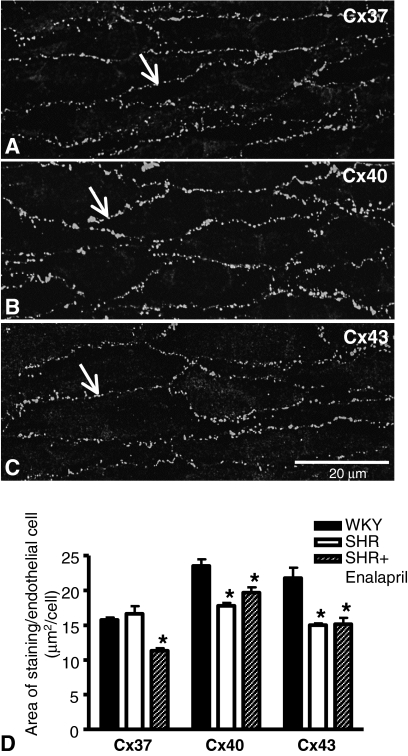

Changes in Morphology within the Arterial Wall among Rat Groups. Immunohistochemical staining for Cxs37, 40, and 43 in whole-mount preparations showed that gap junctions containing these Cxs were primarily localized to endothelial cell perimeters (Fig. 6, A–C). No clear staining could be detected for any of the Cxs in the smooth muscle cell layers of whole-mount preparations or in transverse sections.

Fig. 6.

Connexin expression in the endothelium of mesenteric arteries. Immunohistochemistry using antibodies against Cxs37 (A), 40 (B), and 43 (C) showed that gap junctions containing these Cxs were primarily localized to endothelial cell perimeters in all rat groups (arrows; WKY rats). Quantification was undertaken using ImageJ, taking into account the endothelial cells sizes presented in Table 3. Data represent means ± S.E.M. for preparations taken from three to four rats. *, P < 0.05, compared with WKY rats of the corresponding Cx group.

Using Cx40 immunoreactivity, we found that endothelial cells were significantly smaller in arteries from SHRs than WKY rats and that enalapril treatment did not reverse this effect (Table 4). The length and width of endothelial cells did not differ significantly among the groups, although the perimeter was significantly smaller in the SHRs (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Morphology of endothelial cells

| Group | Area | Perimeter | Length | Width |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm2 | μm | |||

| WKY | 371 ± 30 (6; 250) | 116 ± 8 | 52 ± 4 | 12 ± 1 |

| SHR | 287 ± 27 (4; 160)* | 100 ± 8* | 46 ± 4 | 10 ± 1 |

| SHR + enalapril | 325 ± 31 (3; 75)* | 107 ± 11 | 48 ± 5 | 11 ± 1 |

P < 0.05 compared with WKY. Means and S.E.M. Number of animals and total number of cells in parentheses

Because the endothelial cells varied in size, quantification of Cx staining was determined per endothelial cell. Expression of Cx37 was not significantly different between WKY rats and SHRs but was reduced in enalapril-treated SHRs (Fig. 6D). In contrast, expression of Cxs40 and 43 was significantly reduced in endothelia of arteries from SHRs compared with WKY rats (Fig. 6D). Enalapril treatment did not lead to any significant reversal of these changes (Fig. 6D).

Electron microscopic analysis showed that arteries from SHRs had significantly more smooth muscle cell layers than those from WKY rats, although vessel diameter was not significantly different among the experimental groups (Table 5). Enalapril treatment of SHRs did not produce any significant reduction in the number of layers (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

MEGJs and morphology of the arterial wall

| Group | Number of SMC Layers | Vessel Diameter | Number of MEGJs per EC | Potential MEGJs per EC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | ||||

| WKY | 4.3 ± 0.3 (5) | 205 ± 11 (5) | 0.20 ± 0.05 (4) | 1.68 ± 0.37 (4) |

| SHR | 6.5 ± 0.3 (8)* | 228 ± 16 (8) | 0.05 ± 0.03 (4)* | 0.59 ± 0.05 (4)* |

| SHR + enalapril | 5.8 ± 0.2 (9)* | 186 ± 15 (9) | 0.08 ± 0.03 (4) | 0.67 ± 0.11 (4)* |

SMC, smooth muscle cell; EC, endothelial cell

P < 0.05 compared with WKY. Means and S.E.M. with number of animals in parentheses

Both the number of MEGJs containing pentalaminar membrane (Fig. 7, A and B) and the number of potential MEGJs (Fig. 7, C and D) were significantly reduced in SHRs compared with WKY rats, and this was not altered by treatment with enalapril (Table 5). Projections from one cell layer to the other were not counted as potential MEGJs if there was a clear gap between the cell membranes (Fig. 7E). Pentalaminar gap junctions were readily found among adjacent endothelial cells (Fig. 7F).

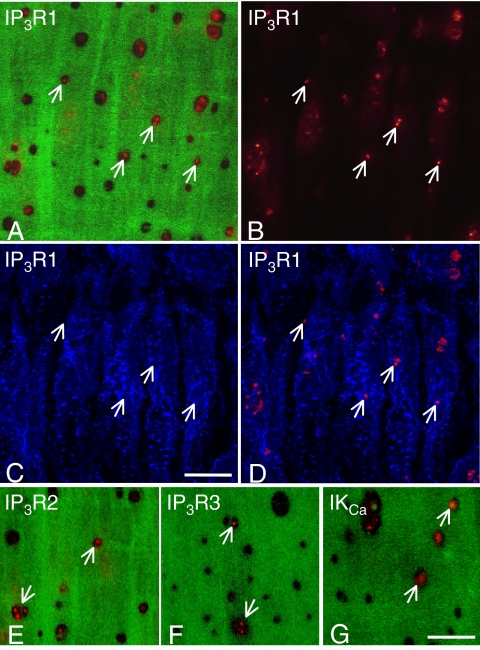

Because MEGJs form on projections of either endothelial or smooth muscle cells that penetrate the IEL (Sandow and Hill, 2000), counts were made of the number of holes in the IEL and expressed per endothelial cell using the data in Table 4. Significantly fewer holes were found in arteries from SHRs and enalapril-treated SHRs than in arteries from WKY rats (Table 6). Punctate staining for IKCa channels and for IP3R1, which were used as markers for myoendothelial projections, was detected within some of the holes in the IEL, above the level of the endothelium (Fig. 8, A–D and G). Comparable staining for IP3R2 was also found, whereas IP3R3 was less prevalent at this level (Fig. 8, E and F). When expressed per endothelial cell, the number of holes showing staining for either IKCa channels or IP3R1 in SHRs or enalapril-treated SHRs was significantly less than that seen in WKY rats (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Table 6). Furthermore, in each rat group, the number of holes showing staining for either IKCa channels or IP3R1 was significantly less than the total number of holes (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Table 6) and significantly less than the total number of MEGJs, including the potential MEGJs (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Tables 5 and 6). The total number of MEGJs per endothelial cell was, in turn, significantly less than the total number of holes in the IEL per endothelial cell in each group (P < 0.05, unpaired Student's t test; Tables 5 and 6, respectively).

TABLE 6.

IKCa and IP3R1 immunoreactivity at the internal elastic lamina

|

Group

|

Number of Holes in IEL/104 μm2

|

Number of Holes in IEL per EC

|

IKCa

|

IP3R1

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Holes with Staining in IEL/104 μm2 | Number of Holes with Staining in IEL per EC | Number of Holes with Staining in IEL/104 μm2 | Number of Holes with Staining in IEL per EC | |||

| WKY | 117 ± 5 (43) | 4.3 ± 0.2 (43) | 13 ± 1 (12) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (12) | 15 ± 3 (10) | 0.6 ± 0.1 (10) |

| SHR | 69 ± 6 (38)* | 2.0 ± 0.2 (38)* | 5 ± 1 (12)* | 0.1 ± 0.0 (12)* | 7 ± 1 (9)* | 0.2 ± 0.0 (9)* |

| SHR + enalapril | 73 ± 9 (38)* | 2.4 ± 0.3 (38)* | 7.5 ± 3 (4) | 0.2 ± 0.1 (4)* | 7 ± 1 (6)* | 0.2 ± 0.0 (6)* |

P < 0.05 compared with WKY. Means and S.E.M. with number of fields counted in parentheses. Data for number of holes (fenestrations) in IEL are from seven, six, and six animals, respectively. Data for IKCa and IP3R1 staining are from three to four animals for each group. EC, endothelial cell; IEL, internal elastic lamina

Fig. 8.

Immunohistochemical staining for IP3R1 (A–D), IP3R2 (E), IP3R3 (F) receptors, and IKCa channels (G) within the holes of the internal elastic lamina of mesenteric arteries from WKY rats. A, staining for IP3R1 (red) in optical confocal sections taken through the holes of the internal elastic lamina (green), at the level depicted by the dotted line marked AB in Fig. 7A. B, same field showing only the IP3R1 staining (red) that lies in this focal plane, above the level of the endothelial cell layer (not in focus). C, same field showing only the IP3R1 staining (blue) present in the focal plane through the endothelial cell layer, as shown by the dotted line marked C in Fig. 7A. D, same field with the IP3R1 staining in the holes (red) superimposed on the IP3R1 staining in the endothelial cell layer (blue). Note that the staining in the holes of the internal elastic lamina is not seen in the same focal plane as the staining in the endothelial cell layer (compare arrows in B and C with D). Also note that some of the staining lying in a diagonal line above the lower three arrows in B is actually at the level of the endothelial cell layer because of the uneven nature of the whole-mount preparations and, hence, represents false positives. E to G, similar staining exists within holes of the internal elastic lamina (arrows) in the case of IP3R2 (E), IP3R3 (F) receptors, and IKCa channels (G). Longitudinal axis of the vessel runs top to bottom of each panel. Bars, 10 μm.

Discussion

Heterogeneous mechanisms underlie EDHF responses in small mesenteric arteries of aged SHRs and WKY rats. In WKY rats, EDHF-mediated relaxation comprised gap junction and EET-dependent mechanisms, whereas in SHRs, gap junction-independent mechanisms prevailed, with a prominent role for EET- and hydrogen peroxide-independent BKCa channel activity. Significant morphological changes were also apparent in SHRs, with an increase in smooth muscle cell layers but a reduction in the size of endothelial cells and coupling both within the endothelium and between the endothelium and smooth muscle via MEGJs. Treatment of SHRs with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, enalapril, decreased blood pressure and restored an EET component to the dilation but failed to reverse morphological changes or restore cell coupling and gap peptide sensitivity of EDHF responses.

ACh produced substantial hyperpolarization of smooth muscle cells in all rat groups, and our previous studies showed these responses arise in the endothelium (Goto et al., 2004b). However, the amplitude of hyperpolarization was 30% smaller in SHRs than in WKY rats but restored by enalapril. This reduction was not due to an inability of the endothelium or smooth muscle to hyperpolarize because neither hyperpolarization nor relaxation evoked by K channel openers was affected. The absence of any consistent reduction in ACh-induced relaxation in SHRs may be due to the measurement of relaxation as reversal of phenylephrine-induced tone that produced only 10 mV depolarization, whereas ACh-induced hyperpolarizations were greater than 20 mV (Table 1). However, the reduced hyperpolarization in SHRs may heighten sensitivity to KCa inhibitors.

Serial section electron microscopy revealed fewer MEGJs per endothelial cell in mesenteric arteries of SHRs than WKY rats and fewer holes in the IEL through which endothelial cells project, with neither parameter reversed by enalapril treatment. The incidence of IKCa channels in the IEL, which reflects the presence of MEGJs (Sandow et al., 2006), was similarly reduced. IP3R1, R2, and, to a lesser extent, R3 receptors, were also found in the same location, and their incidence mirrored the changes occurring in MEGJs, suggesting that all three structures are located in endothelial projections. The IP3 pathway was shown previously to be essential to muscarinic receptor signaling in mesenteric arteries (Goto et al., 2007). The reduced MEGJ coupling is unlikely restricted by the IEL holes in SHRs and enalapril-treated SHR arteries because the number of holes still out-numbered the number of MEGJs by 3- to 4-fold. Together with the insensitivity to gap peptides of ACh relaxations in SHRs and enalapril-treated SHRs, the data show that MEGJs in these arteries do not influence EDHF-mediated vasodilation.

Gap junctions that comprised Cxs 40 and 43, but not Cx37, were also decreased in the endothelium of SHR arteries and, like MEGJs, were not changed by enalapril treatment. Previous studies in large, elastic, superior mesenteric arteries of SHRs also described decreases in endothelial Cxs and associated these changes with diminished EDHF responses, both reversed by candesartan treatment (Kansui et al., 2004). A causal link between EDHF and endothelial Cx expression in these arteries was also made after chronic treatment with angiotensin II (Dal-Ros et al., 2009). In contrast, we found no association between reduced endothelial Cxs40 and 43 and EDHF relaxation in the downstream muscular branches of the superior mesenteric artery. Furthermore, although ACh-induced hyperpolarizations in SHRs were restored by enalapril, the alterations to Cxs persisted. Although longer treatments might have reversed changes in endothelial Cx expression, because a trend to reversal was noted with Cx40, the data highlight a dissociation between the effects of the renin-angiotensin system on Cx expression and EDHF-mediated hyperpolarization and point to differences in the regulation of EDHF in large, elastic arteries compared with smaller, muscular arteries.

The absence of change to Cx37 expression in SHR arteries suggests a diminishing relationship between hypertension and this Cx with age. Previous studies have shown 25% less Cx37 in muscular mesenteric arteries of SHRs than WKY rats at 3 months of age (Goto et al., 2004b), whereas this difference was less than 10% at 8 months of age (Kansui et al., 2004). Although changes in endothelial Cxs were reversed after blockade of the renin-angiotensin system in mesenteric and caudal arteries in younger SHRs (Kansui et al., 2004; Rummery et al., 2005), the absence of changes in aged SHRs suggests a developing insensitivity of Cx expression in established hypertension.

Our functional data revealed a role for EETs in EDHF-mediated vasodilatory responses of WKY rats, but not SHRs. EETs are catabolized by soluble epoxide hydrolase, whose expression is up-regulated by angiotensin II (Ai et al., 2007). Thus, when angiotensin II levels are elevated in SHRs, soluble epoxide hydrolase is up-regulated and EETs are reduced (Yu et al., 2000). Consistent with this, ACh-evoked hyperpolarizations and dilations in SHRs were insensitive to the EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE, whereas responses in enalapril-treated SHRs displayed a “restoration” of sensitivity to EEZE, an effect paralleled by the cytochrome P450 inhibitor, miconazole. Experiments using the four EET regioisomers demonstrated that despite elevated EET catabolism, the SHR arteries are capable of relaxing to exogenously applied EETs and do so independently of the endothelium. Although these experiments may suggest that alterations in circulating angiotensin II levels can influence the mechanisms recruited to elicit EDHF, we cannot rule out the possibility that other antihypertensive therapies, which do not directly alter angiotensin II levels, could restore a role for EETs simply through their blood pressure-lowering effects.

The involvement of EETs in EDHF mechanisms in the rat mesenteric artery has been excluded previously because sensitivity to cytochrome P450 inhibitors, like miconazole, could be explained by nonspecific inhibition of KATP channels (Vanheel and Van de Voorde, 1997). However, EDHF relaxations to ACh in our study were insensitive to the KATP channel blocker glibenclamide, and relaxations to the KATP channel opener levcromakalim were not affected by miconazole. It is also unlikely that the selective effect of miconazole in WKY rats, but not SHR arteries, could be attributed to differential KATP activity because we found no differences in responses to levcromakalim between these rat groups. The similarities in the effects of 14,15-EEZE with those of miconazole lend strong support to the idea that EETs contribute to EDHF in our preparation.

EETs act primarily through BKCa channels (Larsen et al., 2008) via G-protein-dependent mechanisms (Li and Campbell, 1997). Lack of any further effect of IbTx over 14,15-EEZE in WKY rats and enalapril-treated SHRs supports an action of EETs via BKCa channels; BKCa channel involvement in EDHF was prominent in all groups after SKCa and IKCa channel blockade. Staining confirmed that BKCa channels were confined to the smooth muscle layers of arteries in all rats, consistent with the site of action of the EET regioisomers. In contrast, SKCa channels were only in the endothelium, whereas IKCa channels were in both endothelium and smooth muscle cell layers. We speculate that overlapping effects of EEZE, IbTx, and gap peptides in WKY rats might indicate an action of EETs on endothelial transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 channels and transfer of calcium through MEGJs into smooth muscle cells to activate BKCa channels (Loot et al., 2008). Absence of a gap junction component to the ACh response in enalapril-treated SHRs suggests that different mechanisms underlie EET actions in the two rat groups, posing tantalizing questions for future studies.

In SHRs, the addition of IbTx had a substantial inhibitory effect on dilation, although the mediator remains unclear because neither EETs nor hydrogen peroxide were involved. An EET-independent BKCa component to EDHF has also been described in the mouse microcirculation (Siegl et al., 2005). Alterations in activity and expression of BKCa channels are well documented during hypertension (Kamouchi et al., 2002) and may arise as a means to offset enhanced vasomotor tone. The attenuation of IbTx sensitivity by enalapril in SHRs is consistent with the reported effects of ramipril on KCa and KV currents in SHR myocytes (Cox et al., 2002).

We found hypertrophic remodeling of the arterial wall in aged SHRs similar to that reported in primary and secondary mesenteric branches of younger rats (Inoue et al., 1990; Yang et al., 2004) but in contrast to eutrophic remodeling of tertiary branches (Intengan et al., 1999). Such variations probably relate to differential pressures exerted in vessels of different size throughout the mesenteric bed (Fenger-Gron et al., 1995). As with gap junctions, enalapril treatment did not reverse hypertrophic remodeling in SHRs, consistent with the effect of quinapril on secondary mesenteric branches, although a longer treatment did show significant reductions in muscle layers (Yang et al., 2004). The absence of an effect of enalapril on the decrease in endothelial cell size seen in SHR arteries in the present study is consistent with our previous work in mesenteric and caudal arteries of younger SHRs (Rummery et al., 2002, 2005; Goto et al., 2004b).

In summary, ACh can evoke comparable EDHF-mediated relaxations in muscular mesenteric arteries from aged normotensive and angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats, albeit through different mechanisms. In WKY rats, relaxations are gap junction- and EET-dependent, whereas in SHRs, EDHF persists in the absence of myoendothelial coupling through the increased importance of BKCa channels, independently of EETs or hydrogen peroxide. Reduction in blood pressure through inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system restored a role for EETs without gap junctional involvement or other morphological alterations. Thus, robust EDHF-mediated responses can be evoked in the absence of myoendothelial coupling, and it is possible that circulating angiotensin II can influence the mechanisms recruited to elicit EDHF dilation.

This work was supported by the National Heart Foundation of Australia [Grant G03C1059]; the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia [Grant 224219]; and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [Grant DK49194].

A.E. and K.G. contributed equally to this work.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.109.152116.

ABBREVIATIONS: EDHF, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; SKCa, small-conductance calcium-dependent potassium channel; IKCa, intermediate-conductance calcium-dependent potassium channel; BKCa, large-conductance calcium-dependent potassium channel; MEGJ, myoendothelial gap junction; EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; WKY, Wistar-Kyoto; ODQ, 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one; ACh, acetylcholine; 14,15-EEZE, 14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid; KATP, ATP-dependent potassium channel; 1-EBIO, 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolinone; KCa, calcium-dependent potassium channel; IbTx, iberiotoxin; TRAM-34, 1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; Cx, connexin; IEL, internal elastic lamina; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

References

- Ai D, Fu Y, Guo D, Tanaka H, Wang N, Tang C, Hammock BD, Shyy JY, and Zhu Y (2007) Angiotensin II up-regulates soluble epoxide hydrolase in vascular endothelium in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 9018-9023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow RS and White RE (1998) Hydrogen peroxide relaxes porcine coronary arteries by stimulating BKCa channel activity. Am J Physiol 275 H1283-H1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor AT, Evans WH, and Griffith TM (1997) Peptides homologous to extracellular loop motifs of connexin 43 reversibly abolish rhythmic contractile activity in rabbit arteries. J Physiol 503 99-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RH, Lozinskaya I, Matsuda K, and Dietz NJ (2002) Ramipril treatment alters Ca(2+) and K(+) channels in small mesenteric arteries from Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 15 879-890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal-Ros S, Bronner C, Schott C, Kane MO, Chataigneau M, Schini-Kerth VB, and Chataigneau T (2009) Angiotensin II-induced hypertension is associated with a selective inhibition of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses in the rat mesenteric artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328 478-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félétou M and Vanhoutte PM (2006) Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: where are we now? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26 1215-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenger-Gron J, Mulvany MJ, and Christensen KL (1995) Mesenteric blood pressure profile of conscious, freely moving rats. J Physiol 488 753-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Edwards FR, and Hill CE (2007) Depolarization evoked by acetylcholine in mesenteric arteries of hypertensive rats attenuates endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factor. J Hypertens 25 345-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Fujii K, Kansui Y, and Iida M (2004a) Changes in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in hypertension and ageing: response to chronic treatment with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31 650-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Fujii K, Onaka U, Abe I, and Fujishima M (2000) Renin-angiotensin system blockade improves endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertension 36 575-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Rummery NM, Grayson TH, and Hill CE (2004b) Attenuation of conducted vasodilatation in rat mesenteric arteries during hypertension: role of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. J Physiol 561 215-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson TH, Haddock RE, Murray TP, Wojcikiewicz RJ, and Hill CE (2004) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor subtypes are differentially distributed between smooth muscle and endothelial layers of rat arteries. Cell Calcium 36 447-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith TM, Chaytor AT, and Edwards DH (2004) The obligatory link: role of gap junctional communication in endothelium-dependent smooth muscle hyperpolarization. Pharmacol Res 49 551-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Masuda T, and Kishi K (1990) Structural and functional alterations of mesenteric vascular beds in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Jpn Heart J 31 393-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intengan HD, Thibault G, Li JS, and Schiffrin EL (1999) Resistance artery mechanics, structure, and extracellular components in spontaneously hypertensive rats: effects of angiotensin receptor antagonism and converting enzyme inhibition. Circulation 100 2267-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakson BE, Ramos SI, and Duling BR (2007) Ca2+ and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated signaling across the myoendothelial junction. Circ Res 100 246-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, Nagao T, Fujishima M, and Ibayashi S (2002) Role of Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels in the regulation of basilar arterial tone in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 29 575-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansui Y, Fujii K, Nakamura K, Goto K, Oniki H, Abe I, Shibata Y, and Iida M (2004) Angiotensin II receptor blockade corrects altered expression of gap junctions in vascular endothelial cells from hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287 H216-H224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BT, Gutterman DD, Sato A, Toyama K, Campbell WB, Zeldin DC, Manthati VL, Falck JR, and Miura H (2008) Hydrogen peroxide inhibits cytochrome P450 epoxygenases: interaction between two endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res 102 59-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PL and Campbell WB (1997) Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids activate K+ channels in coronary smooth muscle through a guanine nucleotide binding protein. Circ Res 80 877-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loot AE, Popp R, Fisslthaler B, Vriens J, Nilius B, and Fleming I (2008) Role of cytochrome P450-dependent transient receptor potential V4 activation in flow-induced vasodilatation. Cardiovasc Res 80 445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchkov VV, Rahman A, Bakker LM, Griffith TM, Nilsson H, and Aalkjaer C (2006) Analysis of effects of connexin-mimetic peptides in rat mesenteric small arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291 H357-H367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather S, Dora KA, Sandow SL, Winter P, and Garland CJ (2005) Rapid endothelial cell-selective loading of connexin 40 antibody blocks endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor dilation in rat small mesenteric arteries. Circ Res 97 399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neylon CB, Nurgali K, Hunne B, Robbins HL, Moore S, Chen MX, and Furness JB (2004) Intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in enteric neurones of the mouse: pharmacological, molecular and immunochemical evidence for their role in mediating the slow afterhyperpolarization. J Neurochem 90 1414-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummery NM, Grayson TH, and Hill CE (2005) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition restores endothelial but not medial connexin expression in hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 23 317-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummery NM, McKenzie KU, Whitworth JA, and Hill CE (2002) Decreased endothelial size and connexin expression in rat caudal arteries during hypertension. J Hypertens 20 247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Bramich NJ, Bandi HP, Rummery NM, and Hill CE (2003) Structure, function, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in the caudal artery of the SHR and WKY rat. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23 822-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Goto K, Rummery NM, and Hill CE (2004) Developmental changes in myoendothelial gap junction mediated vasodilator activity in the rat saphenous artery. J Physiol 556 875-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL and Hill CE (2000) Incidence of myoendothelial gap junctions in the proximal and distal mesenteric arteries of the rat is suggestive of a role in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses. Circ Res 86 341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Neylon CB, Chen MX, and Garland CJ (2006) Spatial separation of endothelial small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (K(Ca)) and connexins: possible relationship to vasodilator function? J Anat 209 689-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Tare M, Coleman HA, Hill CE, and Parkington HC (2002) Involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in the actions of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circ Res 90 1108-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegl D, Koeppen M, Wölfle SE, Pohl U, and de Wit C (2005) Myoendothelial coupling is not prominent in arterioles within the mouse cremaster microcirculation in vivo. Circ Res 97 781-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tare M, Coleman HA, and Parkington HC (2002) Glycyrrhetinic derivatives inhibit hyperpolarization in endothelial cells of guinea pig and rat arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282 H335-H341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggle CR, Hollenberg M, Anderson TJ, Ding H, Jiang Y, Ceroni L, Wiehler WB, Ng ES, Ellis A, Andrews K, et al. (2003) The endothelium in health and disease: a target for therapeutic intervention. J Smooth Muscle Res 39 249-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanheel B and Van de Voorde J (1997) Evidence against the involvement of cytochrome P450 metabolites in endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization of the rat main mesenteric artery. J Physiol 501 331-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikiewicz RJ (1995) Type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J Biol Chem 270 11678-11683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Gao YJ, and Lee RM (2004) Quinapril effects on resistance artery structure and function in hypertension. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 370 444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z and Kaye DM (2006) Endothelial dysfunction and impaired l-arginine transport in hypertension and genetically predisposed normotensive subjects. Trends Cardiovasc Med 16 118-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Xu F, Huse LM, Morisseau C, Draper AJ, Newman JW, Parker C, Graham L, Engler MM, Hammock BD, et al. (2000) Soluble epoxide hydrolase regulates hydrolysis of vasoactive epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Circ Res 87 992-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DX, Mendoza SA, Bubolz AH, Mizuno A, Ge ZD, Li R, Warltier DC, Suzuki M, and Gutterman DD (2009) Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4-deficient mice exhibit impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation induced by acetylcholine in vitro and in vivo. Hypertension 53 532-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]