Abstract

Progressive brain atrophy in HIV/AIDS is associated with impaired psychomotor performance, perhaps partly reflecting cerebellar degeneration, yet little is known about how HIV/AIDS affects the cerebellum. We visualized the 3D profile of atrophy in 19 HIV-positive subjects (age: 42.9+/− 8.3SD) versus 15 healthy controls (age: 38.5+/12.0). We localized consistent patterns of subregional atrophy with an image analysis method that automatically deforms each subject’s scan, in 3D, to match a reference image. Atrophy was greatest in the posterior cerebellar vermis (14.9% deficit) and correlated with depression severity (p=0.009, corrected), but not with dementia, alcohol/substance abuse, CD4+ T-cell counts or viral load. Profound cerebellar deficits in HIV/AIDS (p=0.007, corrected) were associated with depression, suggesting a surrogate disease marker for antiretroviral trials.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, neurodegeneration, magnetic resonance imaging, depression, cerebellum, morphometry, virus, computational anatomy

Introduction

HIV/AIDS is fourth leading cause of death worldwide, and one in every 100 adults aged 15 to 49 is HIV-infected (UNAIDS, 2004). Antiretroviral therapy has greatly increased life expectancy for many of those infected with HIV, but as patients survive longer, there is increasing concern that chronic viral neurotoxicity can lead to progressive brain atrophy and associated neuropsychological/neurocognitive impairment in some patients, which is not resisted by current treatments. Only 15% of those infected have overt dementia, but around 35% of patients exhibit neurocognitive deficits affecting concentration, psychomotor skills and information processing. Cognitive impairments range from minor cognitive motor disorders (MCMD) to HIV-associated dementia, often with a progressive trajectory leading to death (Levy et al., 1985). Other studies suggest that, paradoxically, although antiretroviral treatments have limited penetration of the blood-brain barrier there may be little change in cognitive function over several years so long as peripheral levels of therapeutic drugs are maintained (Cole et al., 2007). Cognitive deficits are thought to result from the effect of HIV on the brain, as they commonly occur in the absence of opportunistic infections, which take advantage of the progressively declining immune system.

HIV infection is associated with progressive striatal, hippocampal, and white matter volume loss, starting in the medically asymptomatic stage, and accelerating later (Archibald et al., 2004; Oster et al., 1995). The few MRI-based studies of HIV/AIDS reveal that atrophy reaches 10–15% in selective brain regions, with a predilection for systems involved in motor control such as the basal ganglia (Chiang et al., 2007; Lepore et al., 2008), and primary, supplementary motor, and prefrontal cortices (Thompson et al., 2005). The caudate and adjacent ventricles are enriched in the virus, so atrophy may progress as the virus spreads out radially into cortical projection areas (Masliah et al., 1997).

Classically defined as a motor control center, the cerebellum is increasingly recognized as contributing to general cognitive processing and emotional control (Schmahmann et al., 2006). Studies in rats have associated HIV infection with increased cerebellar neuronal death (Abe et al., 1996), but little is known regarding the extent of atrophy in HIV patients and how it relates to cognition, although one prior case study found a speech disorder associated with cerebellar dysfunction after HIV infection (Lopez et al., 1994). To further elucidate the connection between HIV and neuropsychological impairment, we mapped the profile of cerebellar atrophy in 3D, and correlated atrophy with neuropsychological measures, depression and dementia ratings, T-cell counts, viral load, and cerebellar function measures. We used a recently validated analysis that fluidly deforms MRI scans onto a common template (Chiang et al., 2007). The applied deformations were analyzed statistically to gauge the level of atrophy, visualizing systematic differences between patients and controls. We hypothesized that the cerebellar vermis would show greatest atrophy, so we also hand-traced cerebellar subregions using a standardized protocol, for additional anatomic validation.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

All 34 subjects were identically scanned with 3D volumetric SPGR (spoiled gradient echo) T1-weighted brain MRI (256×256×124 matrix; 24 cm field of view; 1.5 mm slices, zero gap; flip angle, 40 degrees, echo/repetition time: TE=5 ms, TR=25 ms). 19 subjects were HIV-positive AIDS patients (mean age 42.9 +/− 8.3SD, 3 females/16 males) and 15 were matched HIV-seronegative healthy control subjects with similar HIV-related risk factors to the AIDS patients (age: 38.5 +/− 12.0, 5 females/10 males). All patients met CDC criteria for AIDS, and none had HIV-associated dementia (patients’ mean CD4+ T-cell count was 448.0+/320.9 SD; patients’ mean log10 viral load was 2.53 +/− 1.17 RNA copies per mL blood plasma). AIDS patients seen in the sentinel offices and clinics of an Allegheny County (Pennsylvania) health care provider network were approached for participation by their treating physician. All AIDS patients were eligible to participate, excluding only those with a history of central nervous system opportunistic infections, lymphoma, or stroke. Demographic data for this cohort are reported in (Becker et al., 2004). The study was IRB approved and all subjects gave informed consent.

Neurobehavioral Assessment

Briefly, each subject underwent a detailed neurobehavioral assessment within four weeks prior to their MRI scan, involving a neurological exam, psychosocial interview, and neuropsychological testing, including (1) a semi-structured psychiatric interview, modified from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSMIIIR (SCID; Spitzer, 1989) administered by a trained interviewer; (2) the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1992) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Cummings et al., 1994; NPI) to assess subclinical psychiatric symptoms; and (3) Heaton’s Patient’s Assessment of Own Function questionnaire (Heaton, 1981) and the Modified Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (Lawton and Brody, 1969) and (4) measures from multiple cognitive domains, sensitive to AIDS-related cognitive impairments (Becker et al., 2004). Detailed neurocognitive test data from a partially overlapping set of subjects is summarized in (Thompson et al., 2005), and included tests of psychomotor speed, estimated IQ (Spreen and Strauss, 1998), and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (Wechsler, 1981). Depression and substance abuse were established based on DSM-IV criteria applied to the results from the structured interview. A diagnosis of HIV-Associated Dementia was established after a review of study results (JTB, HJA, OLL) using the current NIMH/NINDS Consensus Criteria (Antinori et al., 2007).

Image Processing

All MRI scans were aligned via linear (9-parameter) scaling to the standardized coordinate system of the ICBM-53 average brain to correct for global inter-subject differences in brain scale. The resulting images were hand-edited to include only the cerebellum, and aligned using a 9-parameter global scaling transform to a cerebellum-only ICBM-53 template to further improve inter-subject alignment. Tensor-based morphometry was performed, as detailed in Chiang et al. (2007). Briefly, cerebellar images were fluidly deformed in 3D to match a Mean Deformation Template (MDT), i.e., a standard brain image created by applying the average deformation field of all 34 subjects warped onto one randomly selected temporary target to that temporary target. Such a customized template avoids bias towards one group in the level of any registration errors.

Statistics

In TBM, maps of the local expansion factor (sometimes called the Jacobian determinant) between the mean template and each individual encode the local differences in volume between each individual and the template, after global volume differences are discounted (these global differences examined in the region-of-interest analysis below). At each image voxel in the cerebellum, a linear statistical model assessed whether local volume at that point depended on: (1) diagnosis, (2) cognitive impairment, (3) depression scores, (4) CD4+ T-cell counts, (5) viral load (after logarithmic transformation), (6) cerebellar function, and (7) alcohol and substance abuse. The p-value describing the significance of this linkage was plotted at each point in the cerebellum using a color code to produce a significance map. Color-coded statistical maps also visualized local volume differences between AIDS patients and controls. The spatial maps (uncorrected) visualize the spatial patterns of cerebellar degeneration (Figure 1). Permutation testing and positive false discovery rate methods (pFDR; Storey, 2002) were used to compute their overall significance (implemented as in Chiang et al., 2007). Each of these two commonly used alternative methods gives overall p- and pFDR values for maps of observed effects, corrected for multiple comparisons, and represents the likelihood of the observed pattern of group differences being found by chance. The overall p-value in permutation testing was computed by comparing the number of voxels of the largest suprathreshold cluster (the suprathreshold cluster was defined as voxels with significance p-value less than 0.01) in the true labeling to the permutation distribution. Finally, to create simple summary measures of volumetric deficits, manually-traced delineations of the anterior, posterior and inferior vermis were performed following a standardized protocol, by a rater blind to diagnosis and other demographic data (S.L.; see Figure 2).

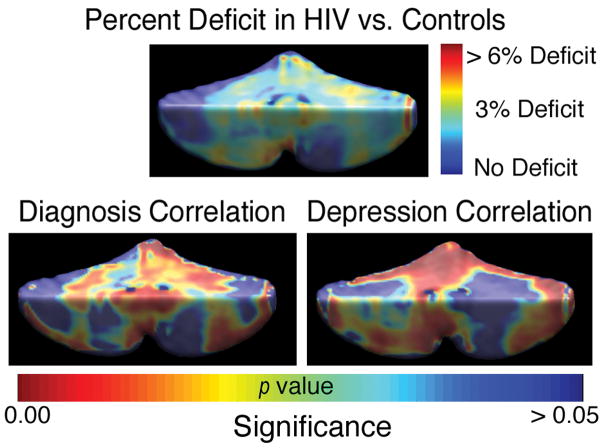

Figure 1. Mapping Cerebellar Atrophy.

Tissue volumes are reduced by 3–6%, on average, in the HIV group versus controls (top map). The level of atrophy is associated with diagnosis (bottom left; p=0.007, corrected) and with depression severity in the patient group (p=0.009, corrected, bottom right).

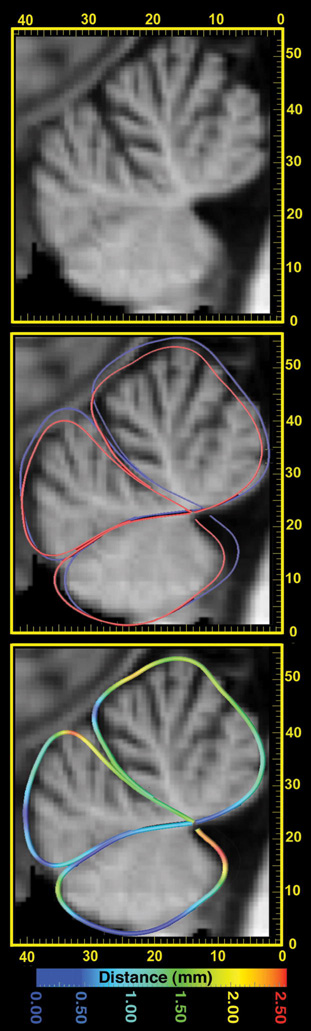

Figure 2. Atrophy in the Cerebellar Vermis.

Here a sagittal section through a patient’s MRI scan is shown (left panel; scale is in mm). Outlines of the anterior, posterior and inferior vermis are shown (middle panel), as average shape contours for the HIV group (red) and controls (blue). After global registration of all images, the distance was plotted (as in Thompson et al., 1998) between the mean HIV and mean normal traces. As this distance is less than 2.5mm everywhere (color-coded, right panel), this level of atrophy would be hard to appreciate by visual inspection of MRI in a single sagittal section, without additional computational analysis.

Results

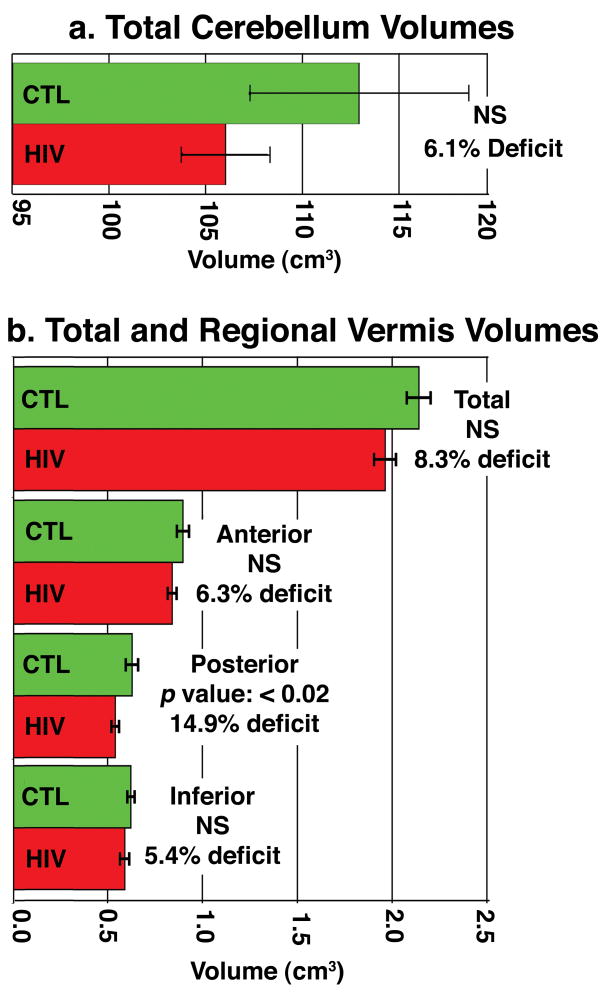

As shown in Figure 1, significant mean volume reductions (around 3–6%) were detected throughout the cerebellum in the HIV group versus controls, with both permutation-corrected and pFDR values of p=0.007 and p=0.014, respectively, for the one-tailed test of atrophy in HIV. Within the HIV cohort, significant correlations were found between the level of atrophy and depression scores (p=0.009, permutation test; pFDR=0.035). Maps of these associations implicated regions that overlapped with the disease effect, with greatest effect sizes at the cerebellar midline (see Figure 2). No significant correlations were detected between cerebellar atrophy and the presence of alcohol abuse, substance abuse, measures of dementia or cerebellar function, or with CD4+ T-cell counts or viral load. Average hand-traced contours at midline showed the posterior cerebellar vermis in HIV was contracted by around 2.5mm relative to the mean contour in controls. Consistent with this, in region of interest analyses (Figure 3), the posterior cerebellar vermis showed deficits (~14.9%; p<0.02). Disease-related differences showed greater effect sizes in the maps than in the volumetric analyses, perhaps partly because effects were not completely uniform within traditionally-defined regions of interest (as shown in the maps).

Figure 3. Volumetric Deficits in HIV/AIDS.

In a post hoc volumetric analysis, overall cerebellar volumes were only 5.1% lower on average in HIV/AIDS (a), but cerebellar subregion deficits reached 14.9% (p<0.02) in the posterior vermis. Strictly speaking, the posterior vermis deficits would only be considered a trend, if a strict Bonferroni correction were applied for the number of regions assessed. The maps of volumetric differences detected atrophy more powerfully - the disease effect was significant after rigorous multiple comparisons correction (either using permutation or FDR methods).

Discussion

HIV/AIDS-related atrophy was prominent in midsagittal cerebellar regions, including the posterior vermis (14.9%; p<0.02), even though mean cerebellar volume was only 5.1% smaller. These tissue reductions correlated with depression ratings.

The cellular basis of these volumetric differences cannot be inferred from MRI but they likely reflect neuronal loss secondary to the neurotoxic effects of HIV viral proteins and the toxic products of infected macrophages, as well as secondary effects of associated white matter degeneration. Several case reports describe cerebellar syndrome as a rare initial manifestation of HIV infection, and asymptomatic cerebellar atrophy has been reported in several neuroimaging studies of HIV (reviewed in Puertas et al., 2003). HIV enters the brain within 2 weeks of initial infection (Paul et al., 2002), and damages neurons primarily by stimulating the production of cytokines that are toxic to neurons, leading to excitotoxic cell death, dendritic simplification and neuronal loss (Wiley et al., 1991). Virus-encoded proteins are directly toxic to glutamate-containing neurons (Sardar et al., 1999; Nath et al., 2000), and neuronal degeneration is also observed when infected macrophages, lymphocytes, and microglia release lymphokines and other neurotoxic substances in vitro (e.g., tumor necrosis factor, oxidative radicals, proteases, quinolinic acid, etc.; Heyes et al., 2001). In post mortem studies of HIV-positive patients with cerebellar degeneration, Tagliati et al. (1998) found diffuse loss of neurons in the granule cell layer, white matter degeneration, and cerebellar atrophy. As potential mechanisms for these deficits, Kwakwa and Ghobrial (2001) suggested that, in addition to direct neurotoxic effects of the virus, autoimmune destruction of the Purkinje cells may account for the changes, or an as-yet-unrecognized opportunistic infection (although the subjects in this study were free from opportunistic infections).

It is not clear why the largest volume reduction was found in the vermis. Post mortem studies show diffuse attrition of granule cells, and some of the volume reduction may reflect white matter reduction secondary to neuronal degeneration, as cerebellar granule cells account for almost half of the neurons in the CNS. Cerebellar atrophy may also correlate with concomitant degeneration of limbic and other cortical areas involved in affective regulation, so the correlation with depressive symptoms may be mediated by atrophy in other, distinct brain systems, occurring at the same time as cerebellar atrophy. For example, in Alzheimer’s disease, the severity of apathy is associated with atrophy of the cingulate gyrus, which is involved in emotional regulation, but also with atrophy of the supplementary motor cortices, which typically degenerate at the same time (Apostolova et al., 2007).

Autopsy studies of AIDS patients with minor cognitive motor disorder (MCMD) reveal widespread loss of synapses (Wiley et al., 1991) and reduced dendritic complexity without overt neuronal loss. As the cerebellum is part of a key motor control network, cerebellar atrophy may also contribute to the mild to moderate psychomotor impairments found in 35% of HIV/AIDS patients, and to their risk for impaired cognition in the future.

The hallmark of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is progressive immunosuppression, particularly the depletion of CD4+ T-lymphocytes. HAART therapy restores immune function in most patients, reducing opportunistic infections, but whether HAART can prevent neuropathological progression is controversial. The pathophysiological parameters measured in this study (CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and viral load) were not correlated with the level of cerebellar atrophy. We may have failed to detect a true association due to limited statistical power in a small sample, or the correlation may be low due to the waxing and waning pattern of plasma viral RNA level and T-cell counts in patients undergoing treatment. There is a rising prevalence of a “burn-out” form of HIV encephalopathy in which neuronal degeneration may persist or worsen even in patients with undetectable viral load (Brew, 2004). Although cerebellar degeneration and T-cell depletion may both result from viral infection, treatment may resist one more vigorously than the other, so that the two measures become uncorrelated.

Conclusion

3D cerebellar maps such as these may help in assessing how HIV affects the brain, and may be useful for gauging the extent of atrophy and treatment efficacy. In the more advanced stages of the disease, around 15% of AIDS patients have HIV-associated dementia, a complex disorder consisting of psychomotor slowing, behavioral abnormalities, and Parkinsonian features such as bradykinesia and gait disturbance (McArthur et al., 2005). Current HAART medications fail to significantly permeate the blood brain barrier (Cysique et al., 2004), so cerebellar degeneration may be present, and be associated with depressive symptoms, even in patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, whose viral load is low. T-cell counts were not linked with cerebellar atrophy (although they associate with cortical and deep nuclear atrophy), suggesting that HIV neurotoxic effects may proceed unchecked when immunosuppression is largely contained.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging (AG021431 to JTB and AG016570 to PMT), the National Library of Medicine, the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the National Center for Research Resources (LM05639, EB01651, RR019771 to PMT). JTB was the recipient of a Research Scientist Development Award - Level II (MH01077).

References

- 1.Levy RM, Pons VG, Rosenblum ML. Central nervous system mass lesions in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) J Neurosurg. 1984;61:9–16. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.1.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole MA, Margolick JB, Cox C, Li X, Selnes OA, Martin EM, Becker JT, Aronow HA, Cohen B, Sacktor N, Miller EN Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Longitudinally preserved psychomotor performance in long-term asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals. Neurology. 2007 Dec 11;69(24):2213–20. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000277520.94788.82. Epub 2007 Oct 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald SL, Masliah E, Fennema-Notestine C, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Heaton RK, Grant I, Mallory M, Miller A, et al. Correlation of In Vivo Neuroimaging Abnormalities With Postmortem Human Immunodeficiency Virus Encephalitis and Dendritic Loss. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:369–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oster S, Christoffersen P, Gundersen HJ, Nielsen JO, Pedersen C, Pakkenberg B. Six billion neurons lost in AIDS: a stereological study of the neocortex. APMIS. 1995;103:525–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang MC, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, Toga AW, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Becker JT, Thompson PM. 3D Pattern of Brain Atrophy in HIV/AIDS Visualized using Tensor-Based Morphometry. NeuroImage. 2006;34:44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leporé N, Brun CA, Chou YY, Chiang MC, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, Lu A, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Toga AW, Becker JT, Thompson PM. Generalized Tensor-Based Morphometry of HIV/AIDS Using Multivariate Statistics on Deformation Tensors. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2008;27(1):129–141. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.906091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson PM, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, Toga AW, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Becker JT. Thinning of the Cerebral Cortex in HIV/AIDS Reflects CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Decline. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:15647–15652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502548102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masliah E, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, Wiley CA, Mallory M, Achim CL, McCutchan A, Nelson JA, Atkinson JH, Grant I the HNRC Group. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:963–972. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmahmann JD, Caplan D. Cognition, emotion and the cerebellum. Brain. 2006;129:290–292. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe H, Mehraein P, Weis S. Degeneration of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and the inferior olivary nuclei in the HIV-1-infected brains: a morphometric analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;92:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s004010050502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Dew MA, Banks G, Dorst SK, McNeil M. Speech motor control disorder after HIV infection. Neurology. 1994 Nov;44(11):2187–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker JT, Lopez OL, Dew MA, Aizenstein HJ. Prevalence of cognitive disorders differs as a function of age in HIV virus infection. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. Instruction manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derogatis L. The brief symptom inventory (BSI): administration, scoring and procedures manual. Clinical Psychometric Research; Baltimore Research: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heaton RK. Wisconsin card sorting manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests. New York; Oxford University Press: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007 Oct 30;69(18):1789–99. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Statist Soc B. 2002;64(Pt 3):479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson PM, Moussai J, Khan AA, Zohoori S, Goldkorn A, Mega MS, Small GW, Cummings JL, Toga AW. Cortical Variability and Asymmetry in Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cerebral Cortex. 1998;8:492–509. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.6.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puertas I, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Gómez-Escalonilla C, Sayed Y, Cabrera-Valdivia F, Rojas R, Sanz-Moreno J. Progressive cerebellar syndrome as the first manifestation of HIV infection. Eur Neurol. 2003;50(2):120–1. doi: 10.1159/000072515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paul R, Cohen R, Navia B, Tashima K. Relationships between cognition and structural neuroimaging findings in adults with human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26(3):353–9. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiley CA, Masliah E, Morey M, et al. Neocortical damage during HIV infection. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:651–657. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sardar AM, Hutson PH, Reynolds GP. Deficits of NMDA receptors and glutamate uptake sites in the frontal cortex in AIDS. Neuroreport. 1999;10:3513–3515. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199911260-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nath A, Haughey NJ, Jones M, Anderson C, Bell JE, Geiger JD. Synergistic neurotoxicity by human immunodeficiency virus proteins Tat and gp120:protection by memantine. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heyes MP, Ellis RJ, Ryan L, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid quinolinic acid levels are associated with region-specific cerebral volume loss in HIV infection. Brain. 2001;124:1033–1042. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.5.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tagliati M, Simpson D, Morgello S, et al. Cerebellar degeneration associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology. 1998;50:244–251. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwakwa HA, Ghobrial MW. Primary cerebellar degeneration and HIV. Arch Intern Med. 2001 2001 Jun 25;161:1555–1556. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.12.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apostolova LG, Akopyan GG, Partiali N, Steiner CA, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, Dinov ID, Toga AW, Cummings JL, Thompson PM. Structural correlates of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2007;24:91–97. doi: 10.1159/000103914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brew BJ. Evidence for a change in AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy and the possibility of new forms of AIDS dementia complex. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McArthur JC, Brew BJ, Nath A. Neurological complications of HIV infection. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(9):543–55. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Brew BJ. Antiretroviral therapy in HIV infection: are neurologically active drugs important? Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1699–1704. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]