Abstract

Dopamine (DA) release varies within subregions and local environments of the striatum, suggesting that controls intrinsic and extrinsic to the DA fibers and terminals regulate release. While applying fast-scan cyclic voltammetry and using tonic and phasic stimulus trains, we investigated the regulation of DA release in the dorsolateral to ventral striatum. The ratio of phasic-to-tonic-evoked DA signals varied with the average ongoing firing frequency, and the ratio was generally higher in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) compared with the dorsolateral striatum. At the normal average firing frequency, burst stimulation produces a larger increase in the DA response in the NAc than the dorsolateral striatum. This finding was comparable whether the DA measurements were made using in vitro brain slices or were recorded in vivo from freely moving rodents. Blockade of the dopamine transporters and dopamine D2 receptors particularly enhanced the tonic DA signals. Conversely, blockade of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) containing the β2 subunit (β2*) predominantly suppressed tonic DA signals. The suppression of tonic DA release increased the contrast between phasic and tonic DA signals, and that made the frequency-dependent DA dynamics between the dorsolateral striatum and NAc more similar. The results indicate that intrinsic differences in the DA fibers that innervate specific regions of the striatum combine with (at least) DA transporters, DA receptors, and nAChRs to regulate the frequency dependence of DA release. A combination of mechanisms provides specific local control of DA release that underlies pathway-specific information associated with motor and reward-related functions.

Dopamine (DA) neurons operate in distinct tonic and phasic timescales to differentiate behaviorally relevant information (Schultz, 2007). DA neurons discharge tonically at low frequencies that consist of individual action potentials without bursts (Grace and Bunney, 1984). Periodically, DA neurons fire in phasic bursts of near 20 Hz and greater (Hyland et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2004). Evidence indicates that phasic or burst firing induces greater extracellular DA release compared with tonic, single-spike firing activity (Gonon, 1988; Grace, 1991; Floresco et al., 2003). Those tonic and phasic signals arise from midbrain DA neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) that innervate the whole dorsal to ventral extent of the striatum. Although the DA neurons that project to the prefrontal cortex may have higher discharge rates (Chiodo et al., 1984; Lammel et al., 2008), many midbrain DA neurons often exhibit similar overall firing properties (Schultz, 1986; Clark and Chiodo, 1988; Gariano et al., 1989; Robinson et al., 2004). Reward-related sensory input, however, such as that initiated by an addictive drug, enhances DA release to varying degrees depending on the dopaminergic pathway and target region (Pontieri et al., 1996; Nisell et al., 1997; Shi et al., 2000; Di Chiara et al., 2004; Janhunen and Ahtee, 2007). These findings suggest that there are local processes that regulate the decoding of reward-related DA impulses and thereby modulate DA release locally.

The relationship between stimulus frequency and DA release varies depending on the local area of interest (Garris and Wightman, 1994; Wu et al., 2002; Cragg, 2003; Montague et al., 2004; Zhang and Sulzer, 2004). One possible explanation for this variability is that DA neurons with similar firing properties have different frequency-dependent DA release depending on the region where they project, which in turn correlates with their anatomical location in the VTA or SNc. Indeed, regional differences in DA release probability and short-term plasticity within the striatum have been reported (Cragg, 2003; Exley et al., 2008). In this study, we analyze tonic and phasic DA release along the dorsal to ventral extent of the striatum while investigating the regulation of release by the dopamine transporter (DAT), the dopamine D2 autoreceptor, and the β2-containing (β2*) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR).

Dopamine influences glutamatergic afferents and striatal medium spiny neuron efferents, thereby modulating striatal output and behavioral consequences (Horvitz, 2002; Nicola et al., 2004). This study was spurred by the hypothesis that the contrast between phasic and tonic DA signals contributes to the functional distinctions between the dorsolateral and ventral striatum. We examined regional differences in the dynamics between tonic and phasic DA signals and how the activity of endogenous factors influences DA signaling dynamics. Those factors included the DATs, the dopamine D2-type receptors, and the β2* nAChRs. The onset, severity, and progression of neurological and psychiatric disorders such as Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia depend on DA signaling. Differences in the regulation of DA release in the dorsal striatum versus the NAc suggest that specific targets for therapeutic drug development may allow mesostriatal and mesolimbic DA signaling to be manipulated separately to aid different patient populations.

Materials and Methods

In Vitro Brain Slice Voltammetry Experiments. Wild-type C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and nAChR β2-subunit null mice were used at 3 to 6 months of age. The β2-subunit null mice were produced and characterized previously (Xu et al., 1999). Mice were housed and handled in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the animal care committee at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX). Under deep anesthesia (a combination of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine), mice were decapitated, and the brains were rapidly dissected out. Sagittal or horizontal slices (350 μm) were cut on a vibratome, incubated at 32 ± 0.5°C for 30 min, held at room temperature for >30 min, and studied at 34 ± 1°C in 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaH2PO3, 1.25 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM glucose saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry was performed using homemade carbon-fiber microelectrodes (10 μm diameter and approximately 100 μm exposed length; Amoco Polymers, Greenville, SC) that were placed in the striatum. This study focused on the dorsolateral striatum and the NAc core and shell. The carbon-fiber electrode potential was linearly scanned (12-ms duration, 10 Hz) from 0 to -400 to 1000 to -400 to 0 mV against a silver/silver chloride reference electrode at a rate of 300 mV/ms. An Axopatch 200B amplifier, a Digidata 1320 interface, and a pClamp 8 system (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA) were used to acquire and analyze data. The voltammograms were sampled at 50 kHz, and the background current was subtracted digitally. The peak oxidation currents for DA in each voltammogram (at approximately 600 mV) were converted into concentration from a postexperiment calibration against fresh solutions of 0.5 to 10 μM dopamine.

Intrastriatal stimuli were delivered using a bipolar tungsten electrode. The two tips of the stimulating electrode were approximately 150 μm away from each other. The tip of the carbon-fiber recording electrode was 100 to 200 μm away from the two tips of the stimulating electrode. The average intraburst firing rate of DA neurons is approximately 20 Hz in rodents (Benoit-Marand et al., 2001; Hyland et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2009), and thus the relationship between the number of pulses (1-20) within a stimulus train and the DA release concentration was commonly determined using a 20-Hz stimulation frequency. Each pulse was 0.5 to 1 ms in duration. After a stable control recording (≥ 30 min), the slices were exposed to a single concentration of GBR 12909 (2 μM), sulpiride (2 μM), or dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE; 0.1 μM) for 20 min before data were collected for drug-induced changes in DA release.

Because stimulus trains of varying length and frequency were used, the release of DA was often spread in time during the length of the stimulus train. To be able to compare the diverse DA release and uptake patterns arising from these stimulus trains, we often quantified the DA signal by using the area under the curve of the DA amplitude plotted against time (micromoles per second). The relative DA signal was calculated by comparing the burst-evoked DA signal to the single-pulse-evoked DA signal. The voltametric recordings from the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell in the same mouse were used to determine the ratio of DA release for the two subregions. For comparison, some experiments also were performed using the NAc core, which displayed DA signaling characteristics intermediate between the dorsolateral striatum and the NAc shell. All data are means ± S.E.M. Comparisons between differences in means were assessed by paired t tests or one-way analysis of variance.

In Vivo Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry Experiments. Rats were implanted with carbon fiber microelectrodes for in vivo fastscan cyclic voltammetry. Surgical preparation used an aseptic technique and anesthesia following the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, administered the long-acting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory carprofen (5 mg/kg s.c.), and placed in a stereotaxic frame. The scalp was swabbed with 10% povidone iodine, bathed with a mixture of lidocaine (0.5 mg/kg) and bupivacaine (0.5 mg/kg), and incised to expose the cranium. Holes were drilled and cleared of dura mater above the NAc (1.3 mm lateral and 1.3 mm rostral from bregma) and the dorsolateral striatum (3.0 mm lateral and 1.3 mm rostral from bregma) and at a convenient location for a reference electrode. Carbon-fiber recording microelectrodes were lowered into the target regions (7.0 and 4.5 mm ventral of dura mater for the NAc core and the dorsolateral striatum, respectively). Placement of the microelectrodes was verified by postexperiment histology.

After recovery from surgery, rats were food-restricted and maintained at 90% of free-feeding body weight for the duration of the experiment. Electrochemical recordings were made in standard operant chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) equipped with a food receptacle located at the center of the side wall. Food-evoked DA release was obtained by delivering an uncued food pellet to the receptacle.

Changes in DA concentration were assessed by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in awake, behaving rats (Phillips et al., 2003). DA was recorded concurrently from the NAc and the dorsolateral striatum using the chronically implanted carbon-fiber microelectrodes. The potential at a carbon fiber microelectrode was held at -0.4 V versus the reference electrode and then ramped to +1.3 V and back to -0.4 V (400 V/s) every 100 ms (10 Hz). The cyclic voltamograms provided a chemical signature that enabled the identification of DA relative to standards. Wave form generation, data collection, and analysis were carried out on a data acquisition system (National Instruments, Austin, TX) coupled to a miniaturized head-mounted voltametric amplifier.

Results

Regional Differences in DA Release in Response to Tonic and Phasic Stimulation. In mouse brain slices, DA signals were evoked by a single-pulse stimulus (1p) or by a stimulus train of 5 pulses (5p) or 20 pulses (20p) delivered at 20 Hz. The amplitude of the DA signal evoked by 1p decreased as the voltammetry measurements moved down ventrally from the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 1a), to the NAc core (Fig. 1b), to the NAc shell (Fig. 1c). The average DA signals to 1p are shown in Fig. 1d. The location with the smallest DA signal to 1p showed the greatest increase in the DA signal to 20p at 20 Hz (Fig. 1, a, b, and c, bottom). The degree of frequency-dependent facilitation was represented as the ratio of the DA signal evoked by 20p delivered at 20 Hz to the DA signal evoked by 1p, [DA]20p/[DA]1p (Fig. 1e). That ratio was inversely related to the DA signal to 1p (Fig. 1d). In the NAc shell, burst stimulation (20p at 20 Hz) caused a rapid increase in the DA release that was larger than in the dorsolateral striatum: 4.7 ± 0.7 μM · s-1 in NAc shell and 2.9 ± 0.5 μM · s-1 in dorsolateral striatum (n = 18-19/group, p < 0.05). This finding indicates that the NAc shell has greater intrinsic ability to respond to burst-firing activity (Cragg, 2003; Exley et al., 2008).

Fig. 1.

DA signals elicited by a signal pulse (1p) or by 5p or 20p given at 20 Hz. a, example traces of DA signals measured using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in the dorsolateral striatum. Bottom, comparison of the DA signal evoked by 1p (broken line) and by a 20p train at 20 Hz (solid gray line). The two sets of different scale bars represent 0.5 μM DA and 2 s.b, example traces of DA signals measured in the NAc core. c, example traces of DA signals measured in the NAc shell. d, the average DA signal evoked by 1p, calculated as the area under the curve, is displayed for the three regions (n = 7-16, **, p < 0.01, compared with the dorsolateral striatum, DS). e, the average phasic/tonic ratio of the DA signal evoked by 20p over 1p ([DA]20p/[DA]1p) is displayed for the three regions (n = 7-16, **, p < 0.01, compared with DS).

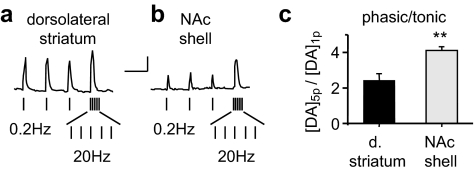

To explore tonic and phasic DA neuron firing activity in greater detail, we applied various stimulus trains. To mimic very slow tonic signaling, we applied stimuli at 0.2 Hz. After the train approached a pseudo steady state, three of those pulses are shown applied to the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 2a) or to the NAc shell (Fig. 2b). The pulses at 0.2 Hz (tonic stimulus) are followed by a phasic stimulus (5p at 20 Hz). With this slow tonic stimulus frequency, there was greater DA release evoked by each stimulus in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 2a). However, the difference between the tonic and phasic evoked release was greater in the NAc shell (Fig. 2b). That result is reflected in the statistically greater ratio of phasic to tonic evoked DA release, [DA]5p/[DA]1p, in the NAc shell (Fig. 2c). Other stimulus patterns, however, produced other effects.

Fig. 2.

The ratio of the phasic-to-slow-tonic DA signals within the dorsolateral striatum and the NAc shell. a, an example DA trace is shown in response to a tonic stimulation (three pulses at 0.2 Hz after achieving pseudo-steady state) followed by a phasic stimulation (5p at 20 Hz) within the dorsolateral striatum. b, an example DA trace is shown in response to the same tonic and phasic stimulation within the NAc shell. Scale bars, 0.2 μM DA and 5 s. c, The average ratio of the phasic-to-tonic DA signal ([DA]5p/[DA]1p) showed a greater contrast in the NAc shell compared with the dorsolateral striatum (n = 4, **, p < 0.01).

The known average background firing frequency of DA neurons is approximately 4 Hz (Grace and Bunney, 1984; Clark and Chiodo, 1988; Hyland et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2009). We matched the average firing frequency with a tonic stimulus (applied at 3.3 Hz) followed by a phasic stimulus (5p at 20 Hz). After the tonic train approached a pseudo steady state, 7 of the 3.3-Hz pulses are shown applied to the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 3a), the NAc core (Fig. 3b), or the NAc shell (Fig. 3c). The pulses at 3.3 Hz (tonic stimuli) were followed by a phasic stimulus (5 p at 20 Hz). With this more biologically relevant tonic stimulus frequency, the response to the tonic stimuli began to blur, giving rise to a background DA level. When the phasic burst was applied, the magnitude of the DA signal increased as the recording was moved from the dorsolateral striatum, to the NAc core, to the NAc shell (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

To mimic biologically realistic tonic and phasic DA neuron firing activity, we applied stimulus trains of 3.3 (tonic) and 20 Hz (phasic). a, an example DA trace is shown in response to a tonic stimulation (seven pulses at 3.3 Hz after achieving pseudo-steady state) followed by a phasic stimulation (5p at 20 Hz) within the dorsolateral striatum. b, an example DA trace is shown in response to the same tonic and phasic stimulation within the NAc core and within the NAc shell (c). d, DA signal (area under the curve) evoked by the phasic train was significantly larger in NAc shell and core than in the dorsolateral striatum (n = 11, 12, and 10, respectively; *, p < 0.05). e, in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry showed that an unexpected food pellet elicited a DA signal in the dorsolateral striatum that was smaller than that in the NAc (n = 10, p < 0.01), consistent with the in vitro slice data above.

The qualitative shape of the DA signal under this biologically relevant stimulus pattern is comparable with that measured with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry applied in vivo to a freely moving rodent (Fig. 3e). Unexpected rewards are known to produce brief burst firing by DA neurons (Schultz et al., 1997). When an unexpected food pellet was given, it caused a greater in vivo DA response in the NAc than in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 3e), consistent with the in vitro data (Fig. 3d). Measured as the area under the curve, the in vivo DA response in the NAc, 0.27 ± 0.05 μM · s-1, was significantly larger than that measured from the dorsolateral striatum, 0.03 ± 0.01 μM · s-1 (n = 10, p < 0.01).

Cellular Mechanisms Involved in Regulating Frequency-Dependent DA Signals. The contrast between tonic and phasic DA release within the striatum led us to examine factors that locally regulate those signals. The dorsolateral striatum was stimulated with one and five pulses at frequencies ranging from 5 to 80 Hz. In control dorsolateral slices, there was a modest increase in DA release evoked at higher frequencies (Fig. 4a, control). The DA signal peaked at approximately 20 Hz (140 ± 6%, n = 19). Inhibition of the dopamine transporter (DAT) with GBR 12909 (2 μM) enhanced the frequency-dependent DA signal, especially at the lower frequencies (≤10 Hz) (Fig. 4, a, GBR, and b, ⋄). Inhibition of the DATs shifted the peak of the DA signal to 10 Hz (182 ± 14%, n = 10, p < 0.01, relative to the DA signal evoked by a single pulse). Inhibition of the dopamine D2-type receptors with sulpiride (2 μM) also enhanced the frequency-dependence at lower frequencies (Fig. 4, a, sulpiride, and b, ▵), and the DA signal peaked at approximately 5 Hz (176 ± 12%, n = 11, p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

The frequency-dependence of DA signals in the dorsolateral striatum in response to inhibition of DATs, dopamine D2-type receptors, and β2* nAChRs. a, example DA traces evoked by 1p or by 5p trains at stimulus frequencies of 5, 20, or 80 Hz. The DA signal was evoked under the following conditions: no inhibition (control), inhibition of DATs with GBR 12909 (GBR, 2 μM), inhibition of D2-type receptors with sulpiride (2 μM), inhibition of nAChRs with DHβE (0.1 μM), and in the presence of all three antagonists (GBR + sul + DHβE). Scale bars, 1 μM DA and 5 s, except in GBR, where the y scale represents 2 μM DA. b, GBR (⋄) and sulpiride (▵) enhanced the relative DA signal (normalized to the DA signal evoked by 1p) at low frequencies compared with the control (▪). c, DHβE (○) elicited robust facilitation of the DA signal at higher frequencies compared with control. d, combining GBR, sulpiride, and DHβE led to an increased DA signal that was comparable in size across stimulus frequencies using either 3p (□) or 5p (plus-box) compared with control (n = 4-12).

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) also modulated the frequency-dependence of DA signaling (Zhou et al., 2001; Rice and Cragg, 2004; Zhang and Sulzer, 2004) in a way that was quite distinct from the modulation caused by DATs or D2 receptors. Inhibition of β2* nAChRs with DHβE (0.1 μM) decreased DA release (Fig. 4a, DHβE), particularly DA release evoked by a single pulse: 80 ± 5% inhibition from control (n = 8, p < 0.01). However, the decrease was inversely related to the stimulus frequency, which resulted (after normalization) in a frequency-dependent increase of DA release in DHβE-treated slices, particularly greater than 10 Hz (Fig. 4, a, DHβE, and c, ○). Simultaneous inhibition of DATs (by GBR), DA D2-type receptors (by sulpiride), and β2* nAChRs (by DHβE) resulted in larger but comparably sized DA signals across all frequencies in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 4, a, bottom, and d).

Under our experimental conditions, 1p-evoked DA release was not significantly changed by the inhibition of GABAA receptors with bicuculline (data not shown), and muscarinic and glutamatergic receptors were not systematically examined. Taken together, these data suggest different roles for the DATs, D2-type receptors, and nAChRs in modulating tonic and phasic DA release in the dorsolateral striatum.

Modulation of the DA Signals Evoked by Bursts of Varying Length. The length of phasic bursts (i.e., the number of spikes per burst) alters DA release (Garris et al., 1994; Floresco et al., 2003). Although longer bursts are expected to increase DA release throughout the striatum, the increase was much larger in the NAc shell than in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that DAT, D2 receptor, and nAChR activity influence the differences in DA release associated with increased burst length. To test this possibility, bursts of differing length (1-10 pulses) were applied at 20 Hz. In the dorsolateral striatum, increasing the burst length enhanced the DA signal only moderately relative to 1p stimulation (control, Fig. 5a, ▪). However, in the NAc shell, the DA signal increased much more as the burst length increased (Fig. 5a, ○), demonstrating a burst-length-dependent facilitation during phasic activity. The DA signal from the NAc core displayed intermediate characteristics, falling between the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 5.

The dorsolateral striatum and the NAc shell respond differently to stimulus trains of 5p or 10p given at 20 Hz. Comparisons of the DA signals evoked by phasic stimulus trains were obtained in the absence (control) or presence of DAT, D2 receptor, and β2* nAChR antagonists. The DA signals were normalized to the response evoked by 1p stimulation under each experimental condition. a, in the absence of antagonists (control), the DA signal in the NAc shell was more responsive to phasic stimulus trains. b, with DATs inhibited by GBR (2 μM, n = 6), the relationship of the two regions remained similar to control. c, with D2-type receptors inhibited by sulpiride (2 μM, n = 6), the relationship of the two regions remained similar to control. d, with nAChRs inhibited by DHβE (0.1 μM, n = 6), the frequency dependence of both regions increased, but the increase was greater in the dorsolateral striatum. Consequently, the frequency dependence of the two regions became more similar after nAChR inhibition.

When normalized to 1p, bath application of GBR (2 μM) and sulpiride (2 μM) did not alter the relative burst-length-dependence of DA release in dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell significantly (Fig. 5, b and c). The difference between the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell remained large (Fig. 5, b and c) and comparable with control (Fig. 5a). In contrast, β2* nAChR inhibition by DHβE (0.1 μM) significantly increased the relative DA release evoked by bursts, particularly in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 5d). This change made the frequency-dependence of the DA signaling of the two regions more similar (Fig. 5d).

The effect of DHβE on the relative DA signal occurred because β2* nAChR inhibition disproportionately decreased tonic DA release evoked by a 1p stimulus compared with phasic DA release evoked by a stimulus train. For example, in the dorsolateral striatum, the relative inhibition with DHβE was ∼80% for a 1p stimulus and ∼50% for a stimulus train (n = 8, p < 0.01) (Fig. 6, a and b). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of DHβE on tonic DA release was significantly greater in the dorsolateral striatum than in the NAc shell (80 versus 60%, p < 0.05). That result is represented by showing the DHβE inhibition of normalized DA signals to 1p in the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell (Fig. 6c). In this case, the DA signal to 1p is scaled to be the same size in the dorsolateral striatum and the NAc shell to show that DHβE inhibition of nAChRs is less effective in the NAc shell. That finding is also seen when the remaining amplitude of the DA signal is shown in a bar graph after DHβE inhibition (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of β2* nAChRs with DHβE (0.1 μM) altered DA signals. a, example DA signals evoked by 1p and by a 5p train given at 20 Hz within the dorsolateral striatum in the absence (control) or presence of DHβE. Scale bars, 0.5 μM DA and 0.5 s. b, the average DA signal evoked by 1p and 5p at 20 Hz in the presence of DHβH normalized to the control response as 100%. c, the DA signal evoked by 1p in the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell in the absence (control) or presence of DHβE. The DA signals are normalized to 1p using different y-scale bars: 0.5 μM DA for the dorsolateral striatum, and 0.1 μM DA for the NAc shell and 0.5 s. d, the average DA signal evoked by 1p in the dorsolateral striatum and by the NAc shell in the presence of DHβH normalized to the control response as 100%.

DAT, D2 Receptor, and β2* nAChR Modulation of Tonic DA Signals. We found that low DA release to a single pulse (1p) correlates with stronger burst facilitation (Fig. 1), and we examined how D2-type receptors, DATs, and β2* nAChRs modulate 1p-evoked DA release in the dorsolateral striatum compared with the NAc shell (Fig. 7). Examples of DA release to 1p in the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell are shown in Fig. 7a. The DA release evoked by 1p ([DA]1p) expressed as a ratio of the dorsolateral striatum to the NAc shell indicates greater release to 1p in the dorsolateral striatum (control ratio = 5.1 ± 0.63, n = 14) (ctrl, Fig. 7, a and b). The magnitude of the DA signal, given as area under the curve (Fig. 7c), confirms that the DA signal to 1p is greater in the dorsolateral striatum (ctrl) than the NAc shell (Fig. 7c, NAc, light gray bar).

Fig. 7.

DA signals evoked by 1p in the absence or presence of antagonists for DATs, D2-type receptors, or β2* nAChRs. a, representative DA signals evoked by 1p from the dorsolateral striatum (gray traces) and the NAc shell (dashed traces). The DA signals were controls (ctrl) or with DATs (GBR, 2 μM), D2-type receptors (sulpiride, 2 μM), or β2* nAChRs (DHβH, 0.1 μM) inhibited. Scale bars, 1 μM DA and 2 s. b, the ratio of the DA signal evoked by 1p in the dorsolateral striatum over that in the NAc shell with and without antagonists as labeled (n = 5-11). c, the average magnitude of DA signal evoked by 1p in the dorsolateral striatum with and without antagonists as labeled (n = 6-19). The bar labeled “β2” represents data from mutant mice lacking the nAChR β2-subunit. The control response in the NAc shell is shown for comparison (last bar, light gray). d, the average ratio of the DA signal evoked by 5p at 20 Hz over that evoked by 1p, [DA]5p/[DA]1p, in the dorsolateral striatum with and without antagonists as labeled (n = 6-19). The control response in the NAc shell is shown for comparison (last bar, light gray). Significance is given as *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with control.

D2-type receptor inhibition (sulpiride, 2 μM) increased the 1p-evoked DA release (Fig. 7a, sul) in the dorsolateral striatum (131 ± 11%, n = 11) and the NAc shell (122 ± 6%, n = 7), calculated as area under the curve, without significantly changing the [DA]1p ratio between the dorsolateral striatum and the NAc shell (Fig. 7b). Likewise, DAT inhibition (GBR, 2 μM) strongly increased the DA signal in the dorsolateral striatum (1032 ± 267%, n = 10) and the NAc shell (762 ± 153%, n = 8) but did not significantly change the [DA]1p ratio (Fig. 7b) between the subregions (n = 6, p > 0.05). In contrast, inhibition of β2* nAChRs (DHβE, 0.1 μM) decreased 1p-evoked DA release in both subregions, and the [DA]1p ratio decreased significantly (2.4 ± 0.49, n = 6, p < 0.01 versus control) (Fig. 7, a and b). Similar results where obtained using mutant mice in which the nAChR β2 subunit was knocked out (Fig. 7c, compare bars DHβE and β2). These results indicate that there are regional differences in β2* nAChR modulation of DA release.

We next analyzed the influence of D2-type receptors, DATs, and β2* nAChRs on the ratio of phasic-to-tonic DA signals. The [DA]1p was increased by sulpiride or GBR application, but the ratio of DA release evoked by a 5p at 20 Hz versus that evoked by 1p, [DA]5p/[DA]1p, did not change in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 7d). Greater frequency-dependent facilitation only occurred when [DA]1p was reduced by blocking β2* nAChR activity (DHβE) or using β2-subunit-null mice. The NAc shell (Fig. 7d, NAc, light gray bar) has an intrinsically low [DA]1p and displays a large control [DA]5p/[DA]1p ratio. These results indicate that inhibition of nAChRs reduced the DA signal to 1p, [DA]1p, and switched the pattern of DA release to favor phasic facilitation in the dorsolateral striatum. With nAChRs inhibited, the dorsolateral striatum displays phasic facilitation, represented by [DA]5p/[DA]1p, that is comparable with that seen in the NAc shell (Fig. 7d, compare the last three bars).

Impact of nAChR β2-Subunit Deletion on the Modulation of DA Release. To confirm the pharmacological effects of β2* nAChR inhibition, we evoked DA release in β2-subunit-null mice (Xu et al., 1999). Using the inhibitor DHβE has the advantage that it is reversible upon washout (Zhou et al., 2001), but the β2-subunit knockout mouse ensures that there are no residual influences. Evoked DA release (1p) was decreased in the dorsolateral striatum of β2* nAChR(-/-) mice (0.16 ± 0.02 μM · s-1, n = 15) compared with wild-type mice (1.03 ± 0.09 μM · s-1, n = 19, p < 0.01) and in the NAc shell (null, 0.08 ± 0.02 μM · s-1, n = 12; wild type, 0.25 ± 0.03 μM · s-1, n = 21; p < 0.01) (Fig. 8, a and b). The difference in the [DA]1p ratio of the dorsolateral striatum to the NAc shell was also reduced in the null mice (ratio 2.0 ± 0.3, n = 12) compared with wild-type mice (5.1 ± 0.6, n = 14, p < 0.01).

Fig. 8.

The frequency-dependence of DA signals from wild-type and nAChR β2-subunit-null mice. a, representative DA signals evoked by 1p and 5p at 20 Hz from wild-type littermates [β2(+/+)] and mutant null mice [β2(-/-)] in the dorsolateral striatum. b, representative DA signals from wild-type [β2(+/+)] and null mice [β2(-/-)] in the NAc shell. c, normalized to the DA signal evoked by 1p in the dorsolateral striatum, the average DA signal is shown for 5p delivered at frequencies ranging from 10 to 80 Hz in null mice [β2(-/-), □] and wild-type mice [β2(+/+), ▪](n = 11 and 15, respectively). d, normalized to the DA signal evoked by 1p in the NAc shell, the average DA signal is shown for 5p at 10 to 80 Hz in null mice [β2(-/-), ○] and wild-type mice [β2(+/+), •]) (n = 11 and 12, respectively).

The frequency-dependent facilitation of DA release was more pronounced in β2-subunit-null mice compared with controls (Fig. 8, c and d), where the 1p DA signal is used to normalize the signal to 5p at different intraburst frequencies. In β2* nAChR(-/-) mice, burst stimuli elicited greater frequency-dependent facilitation in the dorsolateral striatum (Fig. 8, a and c). This change made the frequency-dependent DA response between the subregions more similar. These results are consistent with the pharmacological effects of β2* nAChR inhibition on DA dynamics.

Discussion

Under control conditions, the NAc shell shows much greater phasic facilitation of DA release to stimulus trains than the dorsolateral striatum (Thomson, 2000; Cragg, 2003; Exley et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). Compared with the DA release evoked by a single pulse, the DA signal arising from a high-frequency burst is much greater in the NAc shell than in the dorsolateral striatum. The difference in the frequency-dependence of DA signaling has been hypothesized to arise from the difference in dopaminergic innervation, with regions that receive ascending fibers from the VTA (A10 cell group) showing more phasic facilitation than those regions predominantly innervated by the SNc (A9 cell group) (Davidson and Stamford, 1993; Cragg, 2003).

Using single pulses or stimulus trains to mimic tonic and phasic DA neuron activity, we found that β2* nAChR inhibition disproportionately suppressed tonic DA release compared with phasic release. It should be noted that the nAChRs on DA neurons contain the β2 subunit in various combinations with other subunits, especially α4 and α6 (Salminen et al., 2004; Grady et al., 2007). The DA signaling change caused by nAChR inhibition increased the contrast between phasic and tonic DA signals. In that way, nAChR inhibition increased the relative frequency-dependence of DA release. Moreover, the effect of β2* nAChR inhibition on DA dynamics was more apparent in the dorsolateral striatum than the NAc shell. These pharmacological results were corroborated in nAChR β2-subunit-null mice, which displayed smaller DA signals evoked by single pulses and displayed similar frequency dependent patterns of DA release in the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell.

We also showed that inhibiting D2-type receptors and DATs increased evoked DA release without significantly changing the ratio of phasic-to-tonic DA responses. Inhibition of D2-type receptors and DATs also did not significantly alter the general differences in the DA dynamics between the dorsolateral striatum and NAc shell. Because our direct experimental readout is DA release, we anticipated that the main influence of D2-type receptor inhibition with sulpiride was to prevent DA feedback inhibition onto the D2 autoreceptors on DA terminals. That expectation is consistent with the larger DA release we observed after inhibition (see Figs. 4 and 7). However, sulpiride will inhibit both presynaptic and postsynaptic DA D2-type receptors. Because there are differences in function and expression of DATs and D2 receptors along the dorsal-to-ventral extent of the striatum (Delle Donne et al., 1997; Centonze et al., 2003), there is potential for varied distributions and roles of D2 receptors. Despite that potential, the first-order influence of sulpiride is probably inhibition of D2 autoreceptors that regulate DA release. This study also demonstrates that β2* nAChRs potently regulate the contrast between phasic and tonic DA signals (Zhang et al., 2009), and the results suggest a stronger local functional role of β2* nAChRs in the dorsolateral striatum than in the NAc.

Significance of β2* nAChR, DAT, and D2 Receptor Modulation of Tonic DA Signals. Much research has shown that the striatum and the midbrain DA neurons that innervate the striatum are important sites of action for nicotine (Grenhoff et al., 1986; Pontieri et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 2001; Picciotto and Corrigall, 2002; Mansvelder et al., 2003; Rice and Cragg, 2004; Zhang and Sulzer, 2004; Dani and Harris, 2005; Zhang et al., 2009). Our findings showed that β2* nAChRs have an important role in the modulation of tonic and phasic DA signals within the striatum. We hypothesize that if the probability of DA release is normally elevated in the dorsolateral striatum (via ongoing β2* nAChR activity), then higher frequency stimulation cannot boost the release much higher. Thus, the facilitation of DA release caused by phasic stimulation is not normally as apparent in the dorsolateral striatum as in the NAc shell.

Various nAChR subtypes that contain the β2-subunit are involved in the modulation of DA release. For example, the α6-subunit (in various subunit combinations with β2) is an important constituent of the nAChRs with high sensitivity to nicotine that regulates DA release (Salminen et al., 2004; Grady et al., 2007; Exley et al., 2008). In addition, nicotine inactivates striatal nAChRs through desensitization (Wooltorton et al., 2003), which reduces local DA transmission with an overall effect similar to that of a nicotinic antagonist. Thus, the relative enhancement of the phasic-to-tonic DA signaling caused by nAChR inhibition could also underlie the type of nicotinic regulation implicated in sensory gating processes or during pauses in cholinergic activity within the striatum (Zhang and Sulzer, 2004; Cragg, 2006; Zhang et al., 2009).

The DAT and the DA D2 autoreceptor both regulate the net extracellular DA concentration and modulate DA transients (Cragg and Rice, 2004). Inhibition of DATs or D2-type receptors enhanced DA signals by slowing reuptake and preventing autoinhibition, respectively. Although their inhibition had more potent effects at low frequencies, DAT and D2 receptor inhibition also has influence over phasic signals. These results are in general agreement with previous studies suggesting that the functional efficacy of the DAT and D2 receptor in regulating DA release decreases as the firing frequency increases (Chergui et al., 1994; Benoit-Marand et al., 2001). Although evidence has shown that DAT density is lower in NAc shell than in the dorsal striatum (Coulter et al., 1996), our results demonstrate that inhibition of DATs elicited meaningful changes in evoked DA concentration in both regions.

Significance of the DA Source and the Target-Specific Variation in DA Release. Microdialysis and voltammetry measurements have shown that the extracellular DA concentration is lower in the NAc than in the dorsal striatum (Jones et al., 1995; Keck et al., 2002; Cragg, 2003; Melendez et al., 2003; Fadda et al., 2005). We found that lower basal DA release (i.e., DA release evoked by 1p) correlated with stronger facilitation of DA release in the NAc shell during phasic stimulation. By contrast. in the dorsolateral striatum, which had higher basal DA release, burst-evoked DA release was relatively constant over a wide range of frequencies (5-80 Hz) and burst lengths (1-20 spikes/burst). These results are in agreement with previous studies that demonstrate an inverse relationship between action potential-evoked release probability and degree of frequency-dependent facilitation (Thomson, 2000; Cragg, 2003; Exley et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009).

A larger and rapid transient extracellular DA signal in the NAc shell compared with the dorsolateral striatum indicates greater intrinsic response to phasic midbrain firing activity, which is consistent with the idea that mesolimbic DA neurons encode salient unpredicted sensory events (Schultz et al., 1997). Conversely, the relative stability of dorsolateral striatal DA release in response to changes in firing rate is consistent with the hypothesis that DA release in the dorsal striatum enables the initiation of cognitive and motor responses but does not necessarily correlate with the induction of movement (Romo and Schultz, 1990). These results may explain previous studies showing that dorsal striatal DA release is not linearly dependent on firing activity (Chergui et al., 1994; Montague et al., 2004). High-frequency signals cannot boost release linearly because the probability of DA release is initially closer to its maximum value in the dorsal striatum. In contrast, the lower release probability in the ventral striatum allows for the amplification of the DA signal across a wide range of firing frequencies, resulting in a continuing positive dependence of release as the burst length increases (i.e., more spikes per burst).

Based on these findings, it is plausible that the postsynaptic elements in the NAc shell (i.e., glutamatergic afferents and medium spiny neurons) experience a larger contrast between the tonic and phasic DA signals after salient or reward-predictive signals arrive compared with the dorsolateral striatum. Dopamine and glutamate terminals often synapse on common dendritic spines on striatal neurons (Bouyer et al., 1984). It is theorized that tonic and phasic DA input onto medium spiny neurons could be a part of the mechanism underlying the dopamine-mediated increase in the signal-to-noise ratio of the glutamatergic input signal (Horvitz, 2002; Nicola et al., 2004). Our results demonstrate that the differences in the contrast between tonic and phasic DA release are intrinsic to each striatal subregion, as is the difference in the origin of the DA afferents. The VTA provides the main dopaminergic innervation to the NAc shell, whereas the SNc provides the main innervation of the dorsolateral striatum. The areas innervated by the VTA, including the medial axis of the striatum and the ventral striatum, show a higher phasic-to-tonic ratio compared with the areas innervated by the SNc, including the dorsolateral striatum. Changes in DA neuron burst firing are particularly important in the ventral striatum, in which fast glutamatergic processing is required for attention and behavioral selection (Grace et al., 2007). The contrast between the tonic and phasic DA signals provides a key neuronal signal that modulates the postsynaptic targets. Thus, lower tonic DA release in the ventral striatum optimizes the contrast between the phasic and tonic signals.

In summary, these results indicate that there are inherent and local regional differences in the dopaminergic afferents and DA signaling within the striatum (Davidson and Stamford, 1993; Cragg, 2003). We suggest that the contrast between phasic and tonic DA signals is a key functional feature that varies within the striatum and that the feature can be endogenously and exogenously modulated by a number of factors. Because neurological and psychiatric disorders such as Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia depend on DA signaling, differences in DA release dynamics and regulation offer an entry target for therapeutic drug development. Separately regulating mesocorticolimbic versus mesostriatal DA signaling could selectively aid patients with schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease, respectively. Potential differences between the mesocorticolimbic and mesostriatal DA pathways are the nAChR subtypes that regulate DA release (Janhunen and Ahtee, 2007). By capitalizing on those differences, DA signaling may be therapeutically manipulated to aid different patient populations depending on their DA signaling needs.

Supplementary Material

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant DA009411]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant NS021229]; a National Research Service Award [F32-DA024540]; and the Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation Parkinson's Disease Program.

ABBREVIATIONS: DA, dopamine; β2*, β2 subunit-containing; DAT, dopamine transporter; DHβE, dihydro-β-erythroidine; nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; NAc, nucleus accumbens; SNc, substantia nigra pars compacta; VTA, ventral tegmental area; GBR, GBR 12909, piperazine, 1-(2-(bis(4-fluorophenyl)methoxy)ethyl)-4-(3-phenylpropyl)-, dihydrochloride; 1p, single-pulse stimulus; 5p, stimulus train of five pulses; 20p, stimulus train of 20 pulses.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

References

- Benoit-Marand M, Borrelli E, and Gonon F (2001) Inhibition of dopamine release via presynaptic D2 receptors: time course and functional characteristics in vivo. J Neurosci 21 9134-9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer JJ, Park DH, Joh TH, and Pickel VM (1984) Chemical and structural analysis of the relation between cortical inputs and tyrosine hydroxylase-containing terminals in rat neostriatum. Brain Res 302 267-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Grande C, Usiello A, Gubellini P, Erbs E, Martin AB, Pisani A, Tognazzi N, Bernardi G, Moratalla R, et al. (2003) Receptor subtypes involved in the presynaptic and postsynaptic actions of dopamine on striatal interneurons. J Neurosci 23 6245-6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chergui K, Suaud-Chagny MF, and Gonon F (1994) Nonlinear relationship between impulse flow, dopamine release and dopamine elimination in the rat brain in vivo. Neuroscience 62 641-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo LA, Bannon MJ, Grace AA, Roth RH, and Bunney BS (1984) Evidence for the absence of impulse-regulating somatodendritic and synthesis-modulating nerve terminal autoreceptors on subpopulations of mesocortical dopamine neurons. Neuroscience 12 1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D and Chiodo LA (1988) Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of identified nigrostriatal and mesoaccumbens dopamine neurons in the rat. Synapse 2 474-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter CL, Happe HK, and Murrin LC (1996) Postnatal development of the dopamine transporter: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 92 172-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg SJ (2003) Variable dopamine release probability and short-term plasticity between functional domains of the primate striatum. J Neurosci 23 4378-4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg SJ (2006) Meaningful silences: how dopamine listens to the ACh pause. Trends Neurosci 29 125-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg SJ and Rice ME (2004) DAncing past the DAT at a DA synapse. Trends Neurosci 27 270-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA and Harris RA (2005) Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nat Neurosci 8 1465-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson C and Stamford JA (1993) Neurochemical evidence of functional A10 dopamine terminals innervating the ventromedial axis of the neostriatum: in vitro voltammetric data in rat brain slices. Brain Res 615 229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delle Donne KT, Sesack SR, and Pickel VM (1997) Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of the dopamine D2 receptor within GABAergic neurons of the rat striatum. Brain Res 746 239-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, Acquas E, Carboni E, Valentini V, and Lecca D (2004) Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology 47 227-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Clements MA, Hartung H, McIntosh JM, and Cragg SJ (2008) Alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 33 2158-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadda P, Scherma M, Fresu A, Collu M, and Fratta W (2005) Dopamine and serotonin release in dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens is differentially modulated by morphine in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice. Synapse 56 29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, West AR, Ash B, Moore H, and Grace AA (2003) Afferent modulation of dopamine neuron firing differentially regulates tonic and phasic dopamine transmission. Nat Neurosci 6 968-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariano RF, Tepper JM, Sawyer SF, Young SJ, and Groves PM (1989) Mesocortical dopaminergic neurons. 1. Electrophysiological properties and evidence for somadendritic autoreceptors. Brain Res Bull 22 511-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA, Ciolkowski EL, Pastore P, and Wightman RM (1994) Efflux of dopamine from the synaptic cleft in the nucleus accumbens of the rat brain. J Neurosci 14 6084-6093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA and Wightman RM (1994) Different kinetics govern dopaminergic transmission in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and striatum: an in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci 14 442-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonon FG (1988) Nonlinear relationship between impulse flow and dopamine released by rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons as studied by in vivo electrochemistry. Neuroscience 24 19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA (1991) Phasic versus tonic dopamine release and the modulation of dopamine system responsivity: a hypothesis for the etiology of schizophrenia. Neuroscience 41 1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA and Bunney BS (1984) The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: single spike firing. J Neurosci 4 2866-2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, and Lodge DJ (2007) Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Neurosci 30 220-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Salminen O, Laverty DC, Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, and Marks MJ (2007) The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem Pharmacol 74 1235-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J, Aston-Jones G, and Svensson TH (1986) Nicotinic effects on the firing pattern of midbrain dopamine neurons. Acta Physiol Scand 128 351-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz JC (2002) Dopamine gating of glutamatergic sensorimotor and incentive motivational input signals to the striatum. Behav Brain Res 137 65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland BI, Reynolds JN, Hay J, Perk CG, and Miller R (2002) Firing modes of midbrain dopamine cells in the freely moving rat. Neuroscience 114 475-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janhunen S and Ahtee L (2007) Differential nicotinic regulation of the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways: implications for drug development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 31 287-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Garris PA, Kilts CD, and Wightman RM (1995) Comparison of dopamine uptake in the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, caudate-putamen, and nucleus accumbens of the rat. J Neurochem 64 2581-2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck ME, Welt T, Müller MB, Erhardt A, Ohl F, Toschi N, Holsboer F, and Sillaber I (2002) Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation increases the release of dopamine in the mesolimbic and mesostriatal system. Neuropharmacology 43 101-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammel S, Hetzel A, Häckel O, Jones I, Liss B, and Roeper J (2008) Unique properties of mesoprefrontal neurons within a dual mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Neuron 57 760-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, De Rover M, McGehee DS, and Brussaard AB (2003) Cholinergic modulation of dopaminergic reward areas: upstream and downstream targets of nicotine addiction. Eur J Pharmacol 480 117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RI, Rodd-Henricks ZA, McBride WJ, and Murphy JM (2003) Alcohol stimulates the release of dopamine in the ventral pallidum but not in the globus pallidus: a dual-probe microdialysis study. Neuropsychopharmacology 28 939-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, McClure SM, Baldwin PR, Phillips PE, Budygin EA, Stuber GD, Kilpatrick MR, and Wightman RM (2004) Dynamic gain control of dopamine delivery in freely moving animals. J Neurosci 24 1754-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Woodward Hopf F, and Hjelmstad GO (2004) Contrast enhancement: a physiological effect of striatal dopamine? Cell Tissue Res 318 93-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisell M, Marcus M, Nomikos GG, and Svensson TH (1997) Differential effects of acute and chronic nicotine on dopamine output in the core and shell of the rat nucleus accumbens. J Neural Transm 104 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PE, Robinson DL, Stuber GD, Carelli RM, and Wightman RM (2003) Real-time measurements of phasic changes in extracellular dopamine concentration in freely moving rats by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Methods Mol Med 79 443-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR and Corrigall WA (2002) Neuronal systems underlying behaviors related to nicotine addiction: neural circuits and molecular genetics. J Neurosci 22 3338-3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Orzi F, and Di Chiara G (1996) Effects of nicotine on the nucleus accumbens and similarity to those of addictive drugs. Nature 382 255-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME and Cragg SJ (2004) Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat Neurosci 7 583-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Smith DM, Mizumori SJ, and Palmiter RD (2004) Firing properties of dopamine neurons in freely moving dopamine-deficient mice: effects of dopamine receptor activation and anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 13329-13334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romo R and Schultz W (1990) Dopamine neurons of the monkey midbrain: contingencies of responses to active touch during self-initiated arm movements. J Neurophysiol 63 592-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, and Grady SR (2004) Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol 65 1526-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W (1986) Responses of midbrain dopamine neurons to behavioral trigger stimuli in the monkey. J Neurophysiol 56 1439-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W (2007) Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu Rev Neurosci 30 259-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, and Montague PR (1997) A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275 1593-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi WX, Pun CL, Zhang XX, Jones MD, and Bunney BS (2000) Dual effects of D-amphetamine on dopamine neurons mediated by dopamine and nondopamine receptors. J Neurosci 20 3504-3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM (2000) Facilitation, augmentation and potentiation at central synapses. Trends Neurosci 23 305-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooltorton JR, Pidoplichko VI, Broide RS, and Dani JA (2003) Differential desensitization and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in midbrain dopamine areas. J Neurosci 23 3176-3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Reith ME, Walker QD, Kuhn CM, Carroll FI, and Garris PA (2002) Concurrent autoreceptor-mediated control of dopamine release and uptake during neurotransmission: an in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci 22 6272-6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Orr-Urtreger A, Nigro F, Gelber S, Sutcliffe CB, Armstrong D, Patrick JW, Role LW, Beaudet AL, and De Biasi M (1999) Multiorgan autonomic dysfunction in mice lacking the beta2 and the beta4 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 19 9298-9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H and Sulzer D (2004) Frequency-dependent modulation of dopamine release by nicotine. Nat Neurosci 7 581-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Zhang L, Liang Y, Siapas AG, Zhou FM, and Dani JA (2009) Dopamine signaling differences in the nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum exploited by nicotine. J Neurosci 29 4035-4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Liang Y, and Dani JA (2001) Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity regulates dopamine release in the striatum. Nat Neurosci 4 1224-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.