Abstract

Comorbidity is associated with worse health outcomes, more complex clinical management, and increased health care costs. There is no agreement, however, on the meaning of the term, and related constructs, such as multimorbidity, morbidity burden, and patient complexity, are not well conceptualized. In this article, we review definitions of comorbidity and their relationship to related constructs. We show that the value of a given construct lies in its ability to explain a particular phenomenon of interest within the domains of (1) clinical care, (2) epidemiology, or (3) health services planning and financing. Mechanisms that may underlie the coexistence of 2 or more conditions in a patient (direct causation, associated risk factors, heterogeneity, independence) are examined, and the implications for clinical care considered. We conclude that the more precise use of constructs, as proposed in this article, would lead to improved research into the phenomenon of ill health in clinical care, epidemiology, and health services.

Keywords: Comorbidity; multimorbidity; chronic disease, etiology

INTRODUCTION

Health care increasingly needs to address the management of individuals with multiple coexisting diseases, who are now the norm rather the exception.1 In the United States, about 80% of Medicare spending is devoted to patients with 4 or more chronic conditions, with costs increasing exponentially as the number of chronic conditions increases.2 This realization is responsible for a growing interest on the part of practitioners and researchers in the impact of comorbidity on a range of outcomes, such as mortality, health-related quality of life, functioning, and quality of health care.3,4

Attempts to study the impact of comorbidity are complicated by the lack of consensus about how to define and measure the concept.3 Related constructs, such as multimorbidity, burden of disease, and frailty are often used interchangeably. There is an emerging consensus that internationally accepted definitions are needed to move the study of this topic forward.3–5

Our purpose is to inform thinking in the research community by reviewing how comorbidity has been conceptualized in the literature and proposing a more precise use of terminology. In doing so, we review and discuss the mechanisms that may underlie the coexistence of 2 or more conditions in a patient, and we consider the implications of this coexistence for clinical care. As little is yet known about how patients with multiple conditions view their illness6,7 or how their perspective relates to professional constructs, the meaning of comorbidity will be examined only from the perspective of health care professionals.

REVIEWING THE CONCEPT OF COMORBIDITY

We searched the literature for available definitions of the concept of comorbidity. Given the lack of specificity for standard search strategies (a PubMed search in MEDLINE, including solely the Medical Subject Heading term “comorbidity” retrieved more than 25,000 records in the last 10 years), we used a structured search based upon previous strategies8,9 (Supplemental Appendix, available online as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/7/4/357/DC1), combined with a snowball method that has proved efficient and reliable.10,11

Several definitions have been suggested for comorbidity based on different conceptualizations of a single core concept: the presence of more than 1 distinct condition in an individual. Although always used as a person-level construct, 4 major types of distinctions are made: (1) the nature of the health condition, (2) the relative importance of the co-occurring conditions, (3) the chronology of presentation of the conditions, and (4) expanded conceptualizations.

Nature of the Health Condition

The nature of the conditions that co-occur have variously included diseases,8,12 disorders,13 conditions,4,5,8,12 illnesses,14 or health problems.15 Some of these terms and concepts can be linked to classification systems, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), or the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC), but the same is not possible for other terms and concepts, making it difficult to use them in a reproducible manner.

Differentiating the nature of conditions is critical to the conceptualization of comorbidity, because simultaneous occurrence of loosely defined entities may signal a problem with the classification system itself.16,17 For example, some would argue that depression and anxiety are not separate entities but part of a spectrum, and, if so, patients with both should not be classified as having comorbidity.

The Relative Importance of the Conditions

Comorbidity is most often defined in relation to a specific index condition,18 as in the seminal definition of Feinstein: “Any distinct additional entity that has existed or may occur during the clinical course of a patient who has the index disease under study.”12 The question of which condition should be designated the index and which the comorbid condition is not self-evident and may vary in relation to the research question, the disease that prompted a particular episode of care, or of the specialty of the attending physician. A related notion is that of complication, a condition that coexists or ensues, as defined in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)-controlled vocabulary maintained by the National Library of Medicine (NLM).

Multimorbidity has been increasingly used to refer to “the co-occurrence of multiple chronic or acute diseases and medical conditions within one person” without any reference to an index condition.6 Dual diagnosis in psychiatry would be a particular example of multimorbidity, where 2 distinct disorders co-exist without any implicit ordering, eg, severe mental illness and substance abuse. Proponents of the concept of multimorbidity tend to focus on primary care, a setting where the identification of an index disease is often neither obvious nor useful.19

Chronology

Time span and sequence are the relevant considerations. The first refers to the span of time across which the co-occurrence of 2 or more conditions is assessed. This concept may either be implicit or explicit in requiring that the various clinical problems co-occur at the same point in time. Synchronous occurrence has not always been the focus in the study of co-occurring mental health conditions, however, where there has been a considerable interest in disorders co-occurring across a period of time but not necessarily at the same time (Figure 1a ▶).11

Figure 1.

Chronologic aspects of comorbidity.

Each block represents the duration of a different comorbid disease. Two comorbid diseases can either be present at the same point in time (vertical arrow), or occur within a given time period without being simultaneously present at any given point in that period (horizontal arrow) (a). Irrespective of the selected time span, the sequence in which the diseases appear is of particular interest in the study of etiological association (b).

A distinct but related issue is the sequence in which comorbidities appear, which may have important implications for genesis, prognosis, and treatment. Patients with established diabetes who receive a new diagnosis of major depression may be very different from patients with major depression who are later have diabetes diagnosed, although from a cross-sectional perspective, both may be viewed as patients with diabetes and depression (Figure 1b ▶).

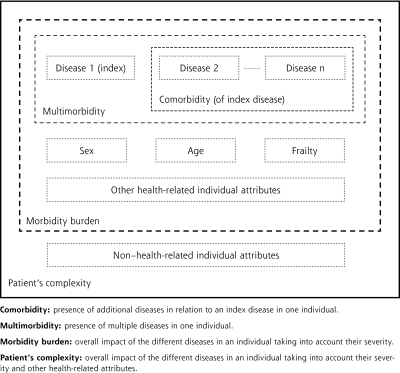

Expanded Conceptualizations: Morbidity Burden and Patient Complexity

Comorbidity has also been used to convey the notion of burden of illness or disease,20 defined by the total burden of physiological dysfunction21 or the total burden of types of illnesses having an impact on an individual’s physiologic reserve.4 This concept is linked to its impact on patient-reported outcomes (including functioning)22 and hence to a related construct in the field of geriatrics, namely, frailty.23

Various approaches have been taken to characterize the combined burden of prespecified diseases or conditions as a single measure on a scale.24 The Charlson Index is one of the most widely used indices, and a recent review identified a dozen others, including the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS), the Index of Coexisting Disease (ICED), and the Kaplan Index.24 Other summary measures have focused on the stratification or classification of patients into groups according to diseases and conditions, age, and sex. Examples include Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACGs),21 Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs),25 and Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs).26 All these aim to take not only the presence but also the severity of different diseases into account. Their primary purpose is to link diagnoses with their impact on the consumption of health care resources or, alternatively, to compare the mix of cases seen by different clinicians while maintaining some broader understanding of the complexity of co-occurring diseases.27

Finally, a newly emerging construct is that of patient complexity. This acknowledges that morbidity burden is influenced not only by health-related characteristics, but also by socioeconomic, cultural, environmental, and patient behavior characteristics.28,29 From a clinical perspective, it will be obvious that disease factors interact with social and economic factors to make clinical management more or less challenging, time-consuming, and resource intensive. Capturing and measuring this complexity, however, remains a challenge.

INTEGRATING THE DIFFERENT CONSTRUCTS

Each construct illuminates a different aspect of morbidity. Consider a 60-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and depression, who is from an ethnic minority, has a low literacy in English, and who cares for her stroke-limited husband. Her mental health professional, focusing on the depression, would consider her diabetes mellitus and hypertension as comorbidities. Her primary care physician might describe her as having multimorbidity, giving equal attention to her diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and depression. Her morbidity burden, as measured by any of the available measures, would be determined by the presence of the different diseases and taking their relative severity into account. Finally, her complexity as a patient would also be shaped by her cultural background, her proficiency in English, and by her personal situation as a whole, including living conditions and not least her role as caretaker for her husband (Figure 2 ▶).

Figure 2.

Comorbidity constructs.

DIFFERENT DEFINITIONS FOR DIFFERING USES

There are 3 main research areas in which it is important to apply and measure these constructs: (1) clinical care, (2) epidemiology and public health, and (3) health service planning and financing.

In clinical research, the construct of choice will be determined by its ability to inform patient management. Although the notion of patient complexity is relevant to all aspects of care, the construct of comorbidity, with its emphasis on an index disease, may be particularly useful in specialist care, which has a strong orientation toward a single (index) disease. Multimorbidity and morbidity burden may prove better constructs for primary care, where the focus is explicitly on the patient as a whole without privileging any one condition. In this context, research into how patients themselves conceptualize comorbidity or multimorbidity and the implications for effective self-management should be a priority.

From an epidemiological and public health perspective, the key issue is the genesis of concurrent diseases. Approaches to the study of genesis and pathways will be reviewed in the next section, but the constructs of comorbidity (index disease) and multimorbidity will both be of interest in this context. They allow for measurement approaches based on counts (presence or absence), thereby providing the necessary information for estimating incidence and prevalence rates. Consideration of chronology in the development of conditions will be of particular importance in this context.

From a health services research and policy perspective, coexisting diseases need consideration when deciding on the allocation of resources. Estimates of future costs will not be well represented as a sum of the costs of the separate illnesses and may well be either greater or less than that sum depending on the nature of the interactions among the coexisting illnesses. Overall burden of disease and patient complexity provide a better conceptualization of the problem for this purpose. Here the use of summary measures may offer new opportunities for quantifying and monitoring population health and its impact on health care utilization and cost and so assist in health care planning. A systematic review of existing indices to determine which is best fit for this purpose would prove valuable.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN COMORBID DISEASES

The coexistence of 2 or more diseases in the same individual raises 2 major clinical questions: whether there is an underlying common etiological pathway, and/or what is their impact on clinical care. For simplicity, we will discuss the situations in which there are only 2 conditions.

Pathways to Comorbidity

A number of different factors determine the overall health of populations and individuals, ranging from genetic and biologic characteristics of the individual to the political and policy context.30 They all play a role in the etiology of any particular disease; hence, they are also expected to play a role in co-occurring diseases. Intuitively, diseases would be expected to cluster in an individual if they shared a common pattern of influences or if the resilience or vulnerability of the individual was altered. But other reasons may explain this clustering.

There are 3 main ways in which different diseases may be found in the same individual: chance, selection bias, or by 1 or more types of causal association. Comorbidity that occurs by chance or selection bias is without causal linkage but is still important because it may lead to erroneous assumptions about causality.

Two diseases can co-occur simply by chance. Consider a population with type 2 diabetes, which affects about 4% of individuals, and eczema which independently affects about 5%. By chance alone, 0.2% (0.04*0.05 = 0.002) of the population would have both eczema and diabetes. An association of importance would therefore need to show a significant departure from this estimate.

Selection bias is an alternative explanation. In his original description of the selection bias affecting patients attending health services, Berkson observed decades ago that disease clusters appeared more frequently in patients seeking care than in the general population,31 almost certainly because patients seeking care were more likely to acquire a diagnosis irrespective of what it was. This type of bias can be avoided using community samples rather than patients attending health services.

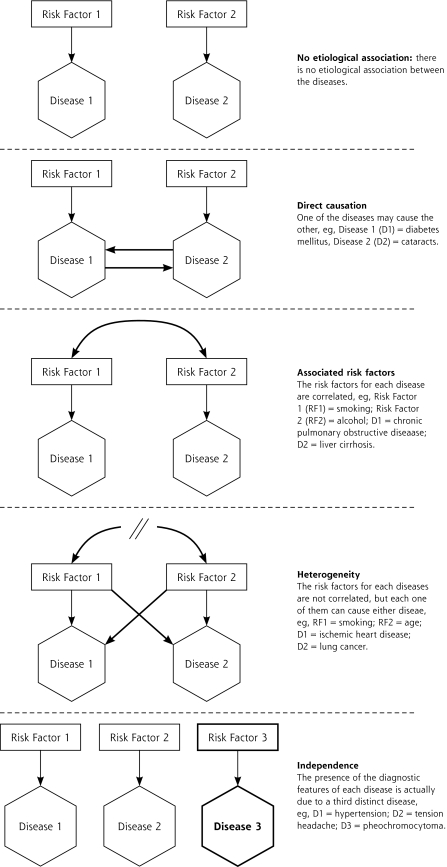

Four models of genuine etiological association between conditions have been described: direct causation, associated risk factors, heterogeneity, and independence (Figure 3 ▶).32

Figure 3.

Etiological models of comorbid diseases.

For ease of presentation, we have only considered 2 different diseases, and 2 corresponding risk factors. Each model relies on the interaction between either diseases or risk factors. The relationships described above apply both to protective factors and to risk factors.32

In the direct causation model, the presence of 1 disease is directly responsible for another. From a clinical perspective, this model would also include the situation in which treatment for 1 disease caused another condition (eg, a anticoagulant given for atrial fibrillation causing a gastrointestinal hemorrhage).

In the associated risk factors model, the risk factors for 1 disease are correlated with the risk factor for another disease, making the simultaneous occurrence of the diseases more likely. For example, smoking and alcohol consumption are correlated; the former is a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the later a risk factor for liver disease, making it more likely the 2 diseases will occur together.

By contrast, in the heterogeneity model, disease risk factors are not correlated, but each is capable of causing diseases associated with the other risk factor (eg, tobacco and age are independent risk factors for a number of malignancies and cardiovascular diseases).

In the independence (distinct disease) model, the simultaneous presence of the diagnostic features of the co-occurring diseases actually corresponds to a third distinct disease. For example, the co-occurrence of hypertension and chronic tension headache might both be due to pheochromocytoma.

These 4 models are not necessarily mutually exclusive and have yet to be applied extensively to the study of comorbidity. All models have, however, been successfully tested by means of simulation and proved empirically valid in the assessment of selected comorbidities.33

Comorbidity and Its Impact on Disease Management

The need to classify comorbid health problems in terms of their relevance to clinical management was recognized early,12 and a number of classification systems have been suggested (Table 1 ▶). These systems are useful and widely reflected in clinical care practice. For example, ischemic heart disease, cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hyper-cholesterolemia), and diabetes are commonly managed within the same cardiovascular clinics in primary care because they share important aspects of disease management. Drawing together patients who have similar clinical management needs may be efficient, but doing so runs the risk of concealing the wider range of ways in which specific diseases may interact in relation to diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and management (including self-management) or outcomes. Even for the same pair of comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes and chronic pulmonary disease), some interventions can be antagonistic (eg, consider the effect of hypoglycemic drugs and corticosteroids on blood glucose), others may be agonistic (physical activity), and others may be neutral. In Table 2 ▶ we show possible interactions between diabetes mellitus and a range of different comorbid clinical entities. Improved understanding of such interactions among comorbid diseases is important to improving clinical care.

Table 1.

Impact of Comorbidity on Clinical Care: Overview of Classification Systems

| Author | Classification | Definition |

| Kaplan et al12,34,35 | Diagnostic comorbidity | “An associated disease [whose]…manifestations can simulate those of the index disease” (eg, pneumonia and pulmonary infarction) |

| Prognostic comorbidity | Diseases “[in relation to an index disease] graded according to their anticipated effects on therapy and life expectancy [as]” | |

| Cogent | “Comorbid ailments expected to impair a patient’s long-term survival” (eg, recent severe stroke) | |

| Noncogent | “Other ailments” (eg, congestive heart failure or myocardial infarction more than 6 months old) | |

| Angold et al16 | Homotypic comorbidity | “Disorders within a diagnostic grouping” (eg, major depression and dysthymia) |

| Heteroptypic comorbidity | “Disorders from different diagnostic groupings” (eg, major depression and conduct disorder)” | |

| Piette and Kerr36 | Concordant comorbidity | “[Diseases as] parts of the same pathophysiologic risk profile and more likely to share the same management and are more likely to be the focus of the same disease management plan” (eg, type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension) |

| Discordant comorbidity | Diseases that are “not directly related in either pathogenesis or management and do not share an underlying predisposing factor” (eg, type 2 diabetes mellitus and irritable bowel syndrome) |

Table 2.

Comorbidity Interactions Using Diabetes as an Example of a Disease That Can Affect the Diagnosis, Treatment, or Prognosis of a Second Disease

| Impact on Clinical Activity | Examples |

| Diagnosis | |

| Made easier by coexisting disease | Most diabetic patients undergo regular fundus examinations, making the diagnosis of unrelated retinal disease, such as age-related macular retinopathy, more likely |

| Made more difficulty by a coexisting disease | Diabetic patients may have altered pain sensation, thereby interfering with and making more difficult the diagnosis of coronary heart disease |

| Treatment | |

| Indicated for existing and coexisting disease | Physical exercise as recommended for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can have a beneficial effect on diabetes |

| Antagonistic effect on coexisting disease | Corticosteroids prescribed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the same patient will have an antagonistic effect on the diabetes treatment |

| Prognosis | |

| Positively modified by a coexisting disease | Mortality associated with diabetes is increased in the presence of peripheral vascular disease |

| Not affected by a coexisting disease | Diabetes is unaffected by the presence of hypothyroidism |

Interactions among chronic diseases have been a particular focus of interest because they may have far-reaching effects on both health and health care.37 But it is no less true that any acute or subacute condition may appreciably affect the management of any other disease.38 A minor acute injury to the right leg, for example, may impair the mobility of a person, thus affecting the management and control of her diabetes; it may also make apparent the presence of osteoarthritis of the left knee that so far had been compensated.

DISCUSSION

Two main limitations of the present work need to be acknowledged. First, although the methods for searching the literature were valid, we cannot be certain that all relevant constructs and definitions have been identified. Second, our focus has been on professional concepts of comorbidity. Although we have occasionally addressed the patient’s perspective, we have not consistently done so throughout the work. In particular, patients’ perspectives on the ways in which multiple conditions affect their health, well-being, and clinical care are highly relevant to the constructs of comorbidity considered here but have not been explicitly addressed.

We have defined the various constructs underpinning the co-occurrence of distinct diseases (comorbidity of an index disease, multimorbidity, morbidity burden, and patient complexity), described how these are interrelated, and shown how different constructs might best be applied to 3 different research areas (clinical care, epidemiology, health services). Future research would benefit by using the explicit definitions for the constructs outlined here in conjunction with established disease classification systems, such as ICD-10, ICPC, or DSM-IV. Doing so would enhance both the precision and generalizability of findings, leading to improved understanding of the causes of co-occurring diseases and their consequences for health service providers and planners. More research into patients’ perspectives on the ways in which multiple conditions affect their health, well-being, and clinical care is needed to complement the professional perspective adopted here and ensure that care is truly patient centered.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: This work has been supported by the National Institutes for Health Research School for Primary Care Research, England.

REFERENCES

- 1.Starfield B. Threads and yarns: weaving the tapestry of comorbidity. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(2):101–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin M, Soubhi H, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, van den Akker M. Multi-morbidity’s many challenges. BMJ. 2007;334(7602):1016–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritchie C. Health care quality and multimorbidity: the jury is still out. Med Care. 2007;45(6):477–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancik R, Ershler W, Satariano W, Hazzard W, Cohen HJ, Ferrucci L. Report of the national institute on aging task force on comorbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(3):275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayliss EA, Edwards AE, Steiner JF, Main DS. Processes of care desired byelderly patients with multimorbidities. Fam Pract. 2008; 25(4):287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF. Barriers to self-management and quality-of-life outcomes in seniors with multimorbidities. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(5):395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Knottnerus JA. Comorbidity or multimorbidity; what’s in a name? A review of the literature. Eur J Gen Pract. 1996;2:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, van den Bos GA. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005. 5;331(7524):1064–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booth A. “Brimful of STARLITE”: toward standards for reporting literature searches. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006. Oct;94(4):421–9, e205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinstein AR. Pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease. J Chronic Dis. 1970;23(7):455–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:137–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wensing M, Vingerhoets E, Grol R. Functional status, health problems, age and comorbidity in primary care patients. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(2):141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan RM, Ong M. Rationale and public health implications of changing CHD risk factor definitions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:321–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schellevis FG, van der Velden J, van de Lisdonk E, van Eijk JT, van Weel C. Comorbidity of chronic diseases in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(5):367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starfield B, Weiner J, Mumford L, Steinwachs D. Ambulatory care groups: a categorization of diagnoses for research and management. Health Serv Res. 1991;26(1):53–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlamangla A, Tinetti M, Guralnik J, Studenski S, Wetle T, Reuben D. Comorbidity in older adults: nosology of impairment, diseases, and conditions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(3):296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valderas JM, Alonso J. Patient reported outcome measures: a model-based classification system for research and clinical practice. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(9):1125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity. a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(3):221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fetter RB, Shin Y, Freeman JL, Averill RF, Thompson JD. Case mix definition by diagnosis-related groups. Med Care. 1980;18(2 Suppl):1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benton PL, Evans H, Light SM, Mountney LM, Sanderson HF, Anthony P. The development of Healthcare Resource Groups—Version 3. J Public Health Med. 1998;20(3):351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espallargues M, Philp I, Seymour DG, et al.; ACMEplus PROJECT TEAM. Measuring case-mix and outcome for older people in acute hospital care across Europe: the development and potential of the ACMEplus instrument. QJM. 2008;101(2):99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nardi R, Scanelli G, Corrao S, Iori I, Mathieu G, Cataldi Amatrian R. Co-morbidity does not reflect complexity in internal medicine patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18(5):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safford MM, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI. Patient complexity: more than comorbidity. the vector model of complexity. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):382–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starfield B. Pathways of influence on equity in health. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(7):1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biomet Bull. 1946;2(3):47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhee SH, Hewitt JK, Lessem JM, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Neale MC. The validity of the Neale and Kendler model-fitting approach in examining the etiology of comorbidity. Behav Genet. 2004;34(3):251–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson EO, Rhee SH, Chase GA, Breslau N. Comorbidity of depression with levels of smoking: an exploration of the shared familial risk hypothesis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(6):1029–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piccirillo JF, Feinstein AR. Clinical symptoms and comorbidity: significance for the prognostic classification of cancer. Cancer. 1996;77(5):834–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan MH, Feinstein AR. The importance of classifying initial co-morbidity in evaluatin the outcome of diabetes mellitus. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27(7–8):387–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Weel C, Schellevis FG. Comorbidity and guidelines: conflicting interests. Lancet. 2006;367(9510):550–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Roland M. Multimorbidity’s many challenges: A research priority in the UK. BMJ. 2007. Jun 2;334(7604):1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]