Abstract

Among putative small molecules that affect sensitivity to acute lung injury, zinc and nitric oxide are potentially unique by virtue of their interdependence and dual capacities to be cytoprotective or injurious. Nitric oxide and zinc appear to be linked via an intracellular signaling pathway involving S-nitrosation of metallothoinein—itself a small protein known to be an important inducible gene product that may modify lung injury. In the present article, we summarize recent efforts using genetic and fluorescence optical imaging techniques to: (1) demonstrate that S-nitrosation of metallothionein affects intracellular zinc homeostasis in intact pulmonary endothelial cells; and (2) reveal a protective role for this pathway in hyperoxic and LPS-induced injury.

Keywords: hyperoxia, LPS, metallothionein, nitric oxide, pulmonary endothelium, zinc

Genome-wide screening has been applied to a number of experimental and clinical conditions, in part, to reveal candidate genes that may modify the course of the relevant pathogenesis and suggest new therapeutic targets. Metallothionein (MT), a small intracellular cysteine-rich metal-binding protein with unique antioxidant activity, has been shown to be upregulated as determined by gene profiling in murine hyperoxic lung injury (1), confirming original observations using subtraction hybridization techniques in hyperoxic rabbit lung (2). Although the functions of MT remain unclear (3), its role in metal ion homeostasis including the binding and release of zinc is apparent. We (4, 5) and others (6–8) have shown that S-nitrosation of MT results in elevations in labile zinc, suggesting a novel nitric oxide (NO)-MT-Zn signaling pathway. Zinc itself appears to have a critical role in cell death decisions and pathways, and is capable of promoting necrosis or inhibiting apoptosis depending upon the experimental conditions and environment (9–15). In the present article, we summarize our understandings of the role of zinc, MT, and NO in the setting of acute lung injury, and suggest that NO-MT-Zn signaling pathway may be especially important in the setting of such injury where abrupt changes in the levels of all these molecules is apparent.

ZINC

Zinc and Lung Biology

After iron, zinc is the most abundant trace essential metal. Unlike iron (or copper), zinc itself is redox inert. Intracellular levels of Zn are maintained by dynamic process (16) of transport, intracellular vesicular storage, and binding to a large number of proteins (estimated at 3% of human genome [17]). As such, Zn is an integral component of numerous metalloenzymes, structural proteins, and transcription factors. In addition to its contribution in metalloregulatory enzymes and proteins, it affects the biophysical properties of cell membranes and appears to have an antioxidant function (18, 19). Although its role in lung is unclear, some insight has recently been gained in the respiratory epithelium (20) and we have begun investigating roles in pulmonary endothelium (21). Truong-Tran and colleagues (22) have suggested that in the respiratory tract, zinc may be an antioxidant, membrane and cytoskeletal stabilizer, essential component of DNA synthesis and cellular growth, participate in wound healing, and in general act as an antiinflammatory molecule. Perhaps because of it pleiotropic nature and/or simplified approaches for supplementation, Zn has become an interesting candidate for pharmacotherapy of a number of pulmonary disorders including upper airway viral infection (23) and asthma (24). Most recently, the efficacy of extracellular zinc in restoring chloride secretion across cystic fibrosis (CF) airway epithelia (25) underscores its potential as adjunct therapy in CF (26).

Zinc and Cell Death

Since our first insights into the process of apoptosis, it has been clear that zinc can act as an inhibitor of this pathway. The initial dogma was that Zn directly inhibited: (1) Ca2+/Mg2+-dependent endonucleases that were responsible for DNA fragmentation (27); (2) the activity of caspase-3, a critical protease in apoptosis (28); or (3) the processing of caspase-3 (12, 29). In Fas-induced apoptosis, Zn does not inhibit cytochrome c release and thus acts somewhere between cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation, perhaps via cytochrome c interactions with capase-9, Apaf-1, or Bcl-XL (30). In gluocorticoid-induced apoptosis, zinc is inhibitory by blocking binding of steroids to gluococorticoid receptors (9). TPEN, a Zn2+/Fe2+ chelator with low affinity for Ca2+, has been useful in revealing a role for Zn inhibition of apotosis (31, 32), and studies with zinc-sensitive fluorophores suggest a role for labile pool of intracellular Zn in apoptosis (33). These approaches have been used by Truong-Tran and colleagues (20) to show that zinc is a survival factor in respiratory epithelium (34, 35), and we recently noted that chelation of zinc results in spontaneous apoptosis of cultured sheep pulmonary artery endothelial cells (SPAEC) (21).

In spite of the above evidence, it is also apparent that zinc can contribute to necrosis, and compelling evidence is especially apparent in the setting of excitotoxicity in the central nervous system (36). Various experimental models of excitotoxicity have shown that Zn accumulates in targeted neurons (37) via an influx of Zn from the extracellular space and is associated with oxidative stress (10, 38). In non-neuronal tissue, the Zn chelator TPEN was capable of reducing peroxynitrite toxicity, in part by inhibition of Zn-dependent nuclear enzyme, poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase (PARS), resulting in less ONOO-induced mitochondrial damage (11). It is noteworthy that like NO, zinc has a dual role in cell death pathways, and as in excitable tissue, we have shown that zinc can actually participate in necrotic cell death in lung endothelial cells (21).

Zinc and Acute Lung Injury

Exposure to extraordinarily high concentrations of zinc (e.g., accidental inhalation of zinc chloride [39]) can produce fatal acute lung injury in humans. In addition, zinc appears to account for a significant aspect of particulate matter toxicity (40–43). Nonetheless, zinc deficiency (secondary to dietary manipulations) enhances hyperoxic lung injury (44), and exogenous zinc is effective in ameliorating hyperoxic (45) or carbon tetrachlordine (46) lung injury. Accordingly, it is apparent that dependent upon its intracellular concentration and changes in the ordinarily low labile pool, zinc can be injurious or cytoprotective, and can be a component of pathogenesis or a target for therapeutic approaches.

METALLOTHIONEIN

Metallothoinein (MT) is a small (6–7 kD) intracellular metal (Zn, Cu, Cd)–binding protein that is ubiquitous to eukaryotes and whose function remains unclear (3, 47). It is capable of binding essential metals such zinc and copper as well as nonessential toxic metals such as cadmium, mercury, and silver. Its extrahepatic constitutive expression is low, but it is readily induced at a transcriptional level by a variety of stimuli including metals themselves and proinflammatory molecules (cytokines, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species). Metal-induced increases in MT gene expression reduce cellular and organismal responses to metals and result in cross resistance to oxidative stress. Accordingly, MT appears to be a stress gene clearly involved in metal detoxification and metal ion homeostasis and perhaps contributing to cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms. Studies in genetically modified mice have clearly supported a functional role for MT in protection against toxic metals (47). The latter function has also received considerable support from transgenic approaches in which overexpression of MT decreases sensitivity to oxidative and nitrosative stress (and conversely targeted deletion of MT genes in null mice enhances sensitivity) in: (1) central nervous system (48–52), (2) skin (53, 54), (3) gastrointestinal tract (55–59), (4) heart (60–64), and (5) lung (65, 66).

MT and Lung Biology

Although intrapulmonary MT levels are low (67), they are readily induced by exposure of intact animals to cadmium (68), paraquat, and tBH (69). Indeed, MT was one of the first hyperoxic sensitive genes revealed in rabbit lung by subtraction hybridization (70), and this observation has been reproduced by new techniques in gene profiling in hyperoxic lung (1, 71), as well as in acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide (65), diesel exhaust particles (72), and ventilator-associated acute lung injury (73). MT also appears to be protective against ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation (66). Gene profiling in other pathologies, including experimental models of diabetes (74) and myocardial infarction (75), also has revealed MT as a candidate molecule. MT protein has been shown to be elevated in hyperoxia (2), and indeed its mRNA is used as an index of sensitivity to hyperoxic injury (76). Exposure of intact animals to aerosolized cadmium produces tolerance to subsequent exposure to high oxygen (77). Alveolar type II cells (78) and alveolar macrophages (79) isolated from rats after repeated exposure to cadmium are resistant to hydrogen peroxide. In humans, MT expression is detectable constitutively in alveolar macrophages, pleural endothelial cells, and basal cells from bronchial epithelium (80).

We noted that overexpression of MT in cultured SPAEC reduced the sensitivity to exposure to 95% oxygen (81). More recently we have noted that mice in which MTI and MTII were deleted by targeted ablation (MT−/−) were more sensitive than wild-type controls (MT+/+) to continuous exposure to > 99% oxygen (B. R. Pitt and coworkers, unpublished observations).

NITRIC OXIDE

Nitric Oxide, S-Nitrosation, and Zinc Sulfur Clusters

Although the reactivity of NO in biological systems is relatively low, secondary reactions involving molecular oxygen, superoxide anion, and transition metals account for much of the biological effects of NO. These reactions produce a complex mixture of reactive nitrogen oxide intermediates (RNOI) that support additional nitrosative reactions at nucleophilic centers, and accordingly most intracellular molecular targets of NO contain cysteines and/or metals (iron) at their allosteric and/or regulatory sites (82). Indeed, the ability of RNOI to S-nitrosate cysteines on over 100 proteins has led several investigators to suggest that nitrosothiols function as post-translational modifications analogous to the better accepted role of protein phosphorylation (83). The specificity of such post-translational modification is predicted to be secondary to thiol nucleophilicity (e.g., pKa) and is affected by allosteric factors (including metal ligand interactions), hydrophobicity of the protein, subcellular localization, and complex aspects of three-dimensional protein structure (82).

In light of these latter considerations, it is not surprising that zinc sulfur clusters represent molecular targets for NO and its reactive nitrogen oxide intermediates. Kroncke, Kolb-Bachofen and colleagues have shown that NO can nitrosate various zinc dependent transcription factors and modify their contribution to gene expression (84). For example, they originally noted that NO caused the release of zinc from Sp1 and EGR-1 (85) resulting in loss of their DNA binding activity. NO also interfered with the dimerization of vitamin D3 receptor and retinoid X receptor affecting their transcriptional activity and in intact cells, NO was shown to inhibit IL-2 expression secondary to its S-nitrosation of zinc dependent transcription factors (86). These authors suggest that NO disruption of zinc fingers is an important aspect of the ability of NO to modify gene expression and outline a schema in which activation and/or inhibition may account for specificity of this novel pathway (86).

NO and Zinc Homeostasis

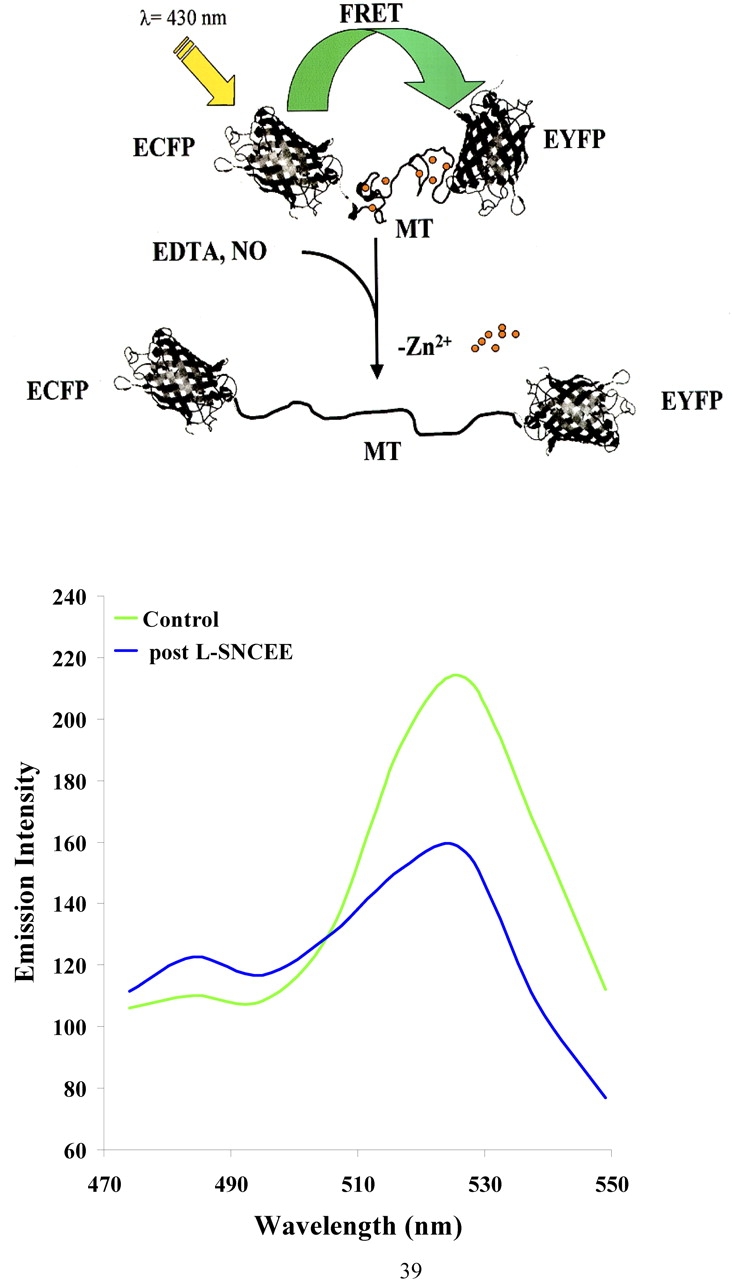

In addition to affecting gene expression, S-nitrosation of zinc sulfur clusters can affect intracellular metal ion homeostasis. The chemical biology underlying this process as well as other redox sensitive aspects of zinc-sulfur complexes has recently been reviewed (87). Kroncke and colleagues originally showed that NO could S-nitrosate the major intracellular zinc-binding protein, MT (84), and cause the release of zinquin-detectable changes in free zinc (6). The effect appeared to be cell-specific in that NO increased detectable labile zinc in endothelial cells, whereas it reduced this signal in cultured pancreatic islet cells (88). Subsequently, Spahl and coworkers (89) noted that iNOS-derived NO increased nuclear Zn and that this increase appeared to require the translocation of MT from cytoplasm to nucleus. We (90, 91) and others (92, 93) confirmed these observations and demonstrated that: (1) S-nitrosation caused conformational changes of MT (via fluorescence resonance energy transfer techniques; Figure 1) in intact pulmonary endothelium consistent with zinc release (4, 94); (2) NO caused an increase in free zinc in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (21, 95); and (3) MT was the requisite target for NO resulting in such changes in free zinc (5). The metal status of MT was critical for resultant NO-mediated changes in that: (1) NO did not cause release of zinc in a cell in which most of the MT was in its apo form (5); and (2) Cu-MT was also nitrosated and depending upon the copper status and the amount of NO exposure, CuMT served as a copper chaperone for apo-ZnSOD (96) or a source of Fenton reactive copper (91). S-nitrosation: (1) requires the presence of molecular oxygen (92, 97), (2) is modified by redox status of the environment (98), and (3) is more facile for the MT-III than other isoforms of MT (93). Collectively, it is apparent that S-nitrosation of zinc sulfur clusters is an important component of NO signaling and that metallothoinein appears to be a critical link between NO and intracellular zinc homeostasis (5, 99).

Figure 1.

A schema of a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) capable reporter molecule (MT) and full spectral report of a single sheep pulmonary artery endothelial cell exposed to the NO donor, L-S-nitrosocysteine ethyl ester (L-SNCEE). In the upper panel, a schema is shown describing the use of a chimera containing cDNA for human MT-IIA sandwiched between enhanced cyan fluorescence protein (ECFP) and enhanced yellow fluorescence protein (EYFP) at N- and C-termini, respectively. Exposure to NO or a metal chelator (EDTA) removes zinc from FRET-MT and causes a conformational change in which the molecule unfolds and the reporter molecules move more distant from each other. In the lower panel, full spectral report is shown by visualizing a single cultured pulmonary artery endothelial cell that was infected with an adenovirus containing cDNA to FRET-MT construct at control and 10 min after exposure to the membrane-permeant NO donor, L-SNCEE. Exposure to L-SNCEE resulted in a decrease in the acceptor and an unquenching of the donor peak. Full spectral reporting was accomplished via the use of a Zeiss 510Meta (Jena, Germany) confocal microscope.

NO and Apoptosis

The importance of NO-mediated cytotoxicity has been appreciated since the L-arginine–NO biosynthetic pathway was first identified in macrophages (100), and has lent credence to the concept of iNOS-derived NO as an important regulator and effector molecule during infection and inflammation affecting tumor cells, microorganisms, and host cells. In a cell-specific fashion, especially under conditions of oxidative stress (e.g., reduced levels of GSH, increased levels of peroxynitrite), NO has clearly been shown to be proapoptotic. In cells such as macrophages, thymocytes, pancreatic islet cells, and tumor cells, NO may be proapoptotic by: (1) activation of mitochondrial pathways (cytochrome c release through mitochondrial membrane potential loss), (2) induction of p53 expression (secondary to DNA damage, (3) activation of JNK/STAT and p38 kinase, or (4) activation of magnesium-dependent neutral sphingomyelinase and ceramide formation (101).

Nonetheless, since the initial observation by Mannick and coworkers (102) that iNOS expression or NO donors inhibited apoptosis in human B lymphocytes, it is now apparent that NO may be antiapoptotic (103) in a cell-specific fashion (hepatocytes, endothelial cells, neurons, eosinophils), especially when produced in low amounts and at moderate rates in a reduced cellular environment. The antiapoptotic effects of NO have been: (1) noted in vitro and in vivo (104), (2) operate in response to a variety of apoptic stimuli (105, 106), (3) can be the result of iNOS (as well as constitutive NOS)-derived NO, and (4) involve both cGMP-dependent and -independent pathways. In this latter regard, cGMP-dependent mechanisms for NO-mediated inhibition of apoptosis are likely to be cell specific and involve PKG-mediated phosphorylation that ultimately suppresses cytochrome c release, ceramide generation, caspase activation, enhanced BCL2 production, or activation of Akt/PKB pathways (101). Relevant to this review are the increasing number of reports suggesting that S-nitrosation of critical proteins (e.g., caspases [107]) and/or NO-mediated induction of antiapoptotic stress genes (e.g., HSP70, HSP32, metallothoinein [108]) are critical components of the ability of NO to inhibit apoptosis.

Important background for the current review were our original observations that direct gene transfer (retroviral or adenoviral-mediated) of iNOS or exposure to NO from chemical donors led to a time-dependent resistance of cultured pulmonary endothelial cells to LPS-induced apoptosis (109). We originally described the ability to stably infect cultured SPAEC with retroviral-mediated human iNOS (110) and not affect their baseline phenotype. Subsequently we showed that adenoviral-mediated iNOS-derived NO or chemical donors of NO reduced the sensitivity of cultured SPAEC (111) to LPS-induced apoptosis. This resistance took 48 h to occur and was associated with inhibition of LPS activation of caspase 3 (95, 105, 111). We were unable to identify the mechanism for such resistance, but it was likely to involve the effect of NO on cellular metabolism and perhaps new gene expression, as it required a minimum of 48 h to be apparent. It was not restricted to SPAEC, as cultured primary hepatocytes could be conditioned with NO to manifest a similar resistant phenotype to TNF-α (and actinomyin) induced apoptosis (112). A survey of 8,000 genes at mRNA level was undertaken under these latter conditions (108). Noteworthy were increases in several stress genes, including metallothionein. Support for a role for MT in mediating such resistance was recently noted (B. R. Pitt and colleagues, unpublished data) when exposure to an NO donor reduced the sensitivity to LPS (plus cycloheximide)-induced apoptosis in cultured pulmonary endothelial cells from wild-type, but not MT−/− mice.

NO and Acute Lung Injury

Although iNOS (113) and reactive nitrogen oxide intermediates (114) are elevated in hyperoxia and may participate in hyperoxia-induced lung injury, it is apparent that under appropriate conditions NO (including iNOS-derived NO) may limit hyperoxic lung injury (115). In this regard: (1) inhalation of NO has been shown to reduce hyperoxia-induced apoptosis in lungs of intact animals (116), (2) pharmacologic inhibition of NO synthesis exacerbates hyperoxic injury (117), and (3) iNOS null mutant mice have enhanced inflammation (accumulation of neutrophils) early in the course of hyperoxia (118). Nonetheless, the potential of NO and its secondary nitrogen oxide intermediates (e.g., peroxynitrite) to contribute to lung injury is also apparent (114). Indeed, Zhu and coworkers (119) reported increased levels of nitrogen monoxides in bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with permeability edema compared to those with hydrostatic edema, and such elevations were associated with decreased alveolar fluid clearance and enhanced nitration of surfactant protein A (SP A). In addition to surfactant proteins (including SP A and B [120]), other targets for NO and/or peroxynitrite include respiratory epithelial sodium channel (121) and chloride channels including cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (122). As such, endogenous NO (or exogenous NO via inhalation of NO gas) has the potential to limit resolution of pulmonary edema and depress host defense of lung, thereby exacerbating acute lung injury.

CONCLUSIONS

The importance of activation of soluble guanylyl cylase in mediating the effects of NO emerged simultaneously with the discovery of the L-arginine–dependent NO biosynthetic pathway. Nonetheless, it is becoming increasingly apparent that non–cGMP-mediated events contribute to the bioactivity of NO. In this regard, an emerging role for S-nitrosation of regulatory proteins has been revealed, and indeed analogies of the importance of such post-translational modification in signaling to the better known pathways of phosphorylation are now well documented. NO and Zinc are two small molecules that contribute to the sensitivity of the lung to acute injury, and as such represent unique components of the pathogenesis of acute lung injury as well as potential therapeutic modalities. They appear linked via a process in which NO and its reactive species (nitrosonium) can S-nitrosate MT and result in increases in labile pool of zinc. Under a variety of conditions, all three molecules (NO, MT, and Zn) can reduce the sensitivity of lung to hyperoxic and LPS-induced injury, and thus there is a need to further evaluate the physiologic significance of NO-MT-Zn signaling pathway. We and others have provided some insight into potential functions that may be modified by this novel signaling pathway, including: (1) vasomotor tone, including myogenic reflex (4) and hypoxic vasoconstriction (B. R. Pitt and colleagues, unpublished observations) in systemic and pulmonary circulation; (2) gene regulation, especially among candidate genes that are regulated by zinc-associated transcription factors (87); and (3) pathways of cell death, including those within neurons of the central nervous system (15) and pulmonary endothelium (21). The molecular subtleties and overlap with existing signaling pathways of the NO-MT-Zn pathway remain to be elucidated.

Funded in part by NIH HL-70807, HL-65697, GM53789, and the American Heart Association. C.M.S. is a Parker B. Francis Fellow and received support from the Giles F. Filley Foundation.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Perkowski S, Sun J, Singhal S, Santiago J, Leikauf GD, Albelda SM. Gene expression profiling of the early pulmonary response to hyperoxia in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;28:682–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piedboef B, Johnston CJ, Watkins RH, Hudak BB, Lazo JS, Cherian MG, Horowitz S. Increased expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP-I) and metallothionein in murine lungs after hyperoxic exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1994;10:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmiter RD. The elusive functions of metallothioneins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:8428–8430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearce LL, Gandley RE, Han W, Wasserloos K, Stitt M, Kanai AJ, McLaughlin MK, Pitt BR, Levitan ES. A role for metallothionein in physiological nitric oxide signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:477–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.St. Croix CM, Wasserloos K, Dineley K, Reynolds I, Levitan ES, Pitt BR. Nitric oxide mediated changes in zinc homeostasis are regulated by metallothionein/thionein. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L185–L193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berendji D, Kolb-Bachofen V, Meyer KL, Grapenthin O, Weber H, Wahn V, Kroncke KD. Nitric oxide mediates intracytoplasmic and intranuclear zinc release. FEBS Lett 1997;405:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Irie Y, Keung WM, Maret W. S-nitrosothiols react preferentially with zinc thiolate clusters of metallothionein III through transnitrosation. Biochemistry 2002;41:8360–8367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang CJ, Jaworski J, Nolan EM, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. A tautomeric zinc sensor for ratiometric fluorescence imaging: application to nitric oxide-induced release of intracellular zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:1129–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraker PJ, Welford WG. A reappraisal of the role of zinc in life and death decisions of cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1997;215:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YH, Park JH, Hong SH, Koh JY. Nonproteolytic neuroprotection by human recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Science 1999;284:647–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virag L, Szabo C. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase (PARS) and protection against peroxynitrite induced cytotoxicity by zinc chelation. Br J Pharmacol 1999;126:769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai F, Truong-Tran AQ, Ho LH, Zalewski PD. Regulation of caspase activation and apoptosis by cellular zinc fluxes and zinc deprivation: a review. Immunol Cell Biol 1999;77:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JY, Kim JH, Palmiter RD, Koh JY. Zinc released from metallothonein-iii may contribute to hippocampal CA1 and thalamic neuronal death following acute brain injury. Exp Neurol 2003;184:337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chimienti F, Aouffen M, Favier A, Seve M. Zinc homoeostasis-regulating proteins: new drug targets for triggering cell fate. Curr Drug Targets 2003;4:323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossy-Wetzel E, Talantova MV, Lee WD, Scholzke MN, Harrop A, Mathews E, Perkins GA, Lipton SA. Crosstalk between nitric oxide and zinc pathways to neuronal cell death involving mitochondrial dysfunction and p38-activated K+ channels. Neuron 2004;41:351–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liuzzi JP, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters. Annu Rev Nutr 2004;24:151–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of human genome. Nature 2001;409:860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdette SC, Lippard SJ. Meeting of the minds: metalloneurochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:3605–3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finney LA, O'Halloran TV. Transition metal speciation in the cell: insights from the chemistry of metal ion receptors. Science 2003;300:931–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truong-Tran AQ, Ruffin RE, Zalewski PD. Visualisation and function of labile zinc in primary and ciliated airway epithelial cells and cell lines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000;279:L1172–L1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Z-L, Wasserloos K, St. Croix CM, Pitt BR. Role of zinc in pulmonary endothelial cell response to oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;281:L243–L249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truong-Tran AQ, Carter J, Ruffin R, Zalewski PD. New insights into the role of zinc in the respiratory epithelium. Immunol Cell Biol 2001;79:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulisz D. Efficacy of zinc against common cold viruses: an overview. J Am Pharm Assoc 2004;44:594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKeever TM, Britton J. Diet and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zsembery A, Fortenberry JA, Lian L, Bebok Z, Tucker TA, Boyce AT, Braumstein GM, Welt E, Bell PD, Sorscher EJ, et al. Extracellular zinc and ATP restore chloride secretion across cystic fibrosis airway epithelia by triggering calcium entry. J Biol Chem 2004;279:10720–10729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantin AM. Potential for antioxidant therapy of cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2004;10:531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bortner CD, Oldenburg NBE, Cidlowski JA. The role of DNA fragmentation in apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol 1995;5:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perry DK, Smyth MJ, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Duriez P, Poirier GG, Hannun YA. Zinc is a potent inhibitor of the apoptotic protease, caspase-3: a novel target for zinc in the inhibition of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1997;25:18530–18533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morana SJ, Wolf CM, Li J, Reynolds JE, Brown MK, Eastman AJ. The involvement of protein phosphatases in the activation of ICE/CED-3 protease, intracellular acidification, DNA digestion, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1996;271:18263–18271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf CM, Eastman A. The temporary relationship between protein phosphatase, mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation in apotosis. Exp Cell Res 1999;247:505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn YH, Kim YH, Song SH, Koh JY. Depletion of intracellular zinc induces protein synthesis-dependent neuronal apotosis in mouse cortical culture. Exp Neurol 1998;154:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shumacker DK, vann LR, Goldberg MW, Allen TD, Wilson KL. TPEN, Zn2+/Fe2+ chelator with low affinity for Ca2+ inhibits lamin assembly, destabilizes nuclear architecture and may independently protect nuclei from apoptosis in vitro. Cell Calcium 1998;23:151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zalewski PD, Forbes IJ, Seamark RF, Borlinghaus R, Betts WH, Lincoln SF, Ward AD. Flux of intracellular labile zinc during apoptosis (gene-directed cell death) revealed by a specific chemical probe, Zinquin. Chem Biol 1994;3:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter JE, Truong-Tran AQ, Grosser D, Ho L, Ruffin RE, Zalewski PD. Involvement of redox events in caspase activation in zinc-depleted airway epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002;297:1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Truong-Tran AQ, Grosser D, Ruffin RE, Murgia C, Zalewski PD. Apoptosis in the normal and inflamed airway epithelium: role of zinc in epithelial protection and procaspase-3 regulation. Biochem Pharmacol 2003;66:1459–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi DW, Koh JY. Zinc and brain injury. Annu Rev Neurosci 1998;21:347–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frederickson CJ, Hernandez MD, McGinty JF. Translocation of zinc may contribute to seizure-induced death of neurons. Brain Res 1989;480:317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YH, Kim EY, Gwag BJ, Sohn S, Koh JY. Zinc-induced cortical neuronal death with features of apoptosis and necrosis: mediation by free radials. Neurosci 1999;89:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Homma S, Jones R, Qvist J, Zapol WM, Reid L. Pulmonary vascular lesions in the adult respiratory distress syndrome caused by inhalation of zinc chloride smoke: a morphometric study. Hum Pathol 1992;23:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kodavanti UP, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Hauser R, Christiani D, Samet JM, McGee J, Richards JH, Costa DL. Pulmonary and systemic effects of zinc-containing emission particles in three rat strains: multiple exposure scenarios. Toxicol Sci 2002;70:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adamson IY, Prieditis H, Hedgecock C, Vincent R. Zinc is the toxic factor in the lung response to an atmospheric particulate sample. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2000;166:111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adamson IY, Vincent R, Bakowska J. Differential production of metalloproteinases after instilling various urban air particle samples to rat lung. Exp Lung Res 2003;29:373–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gavett SH, Haykal-Coates N, Copeland LB, Heinrich J, Gilmour MI. Metal composition of ambient PM2.5 influences severity of allergic airways disease in mice. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111:1471–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor CG, Towner RA, Janzen EG, Bray TM. MRI detection of hyperoxia-induced lung edema in Zn-deficient rats. Free Radic Biol Med 1990;9:229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor CG, McCutchon TL, Boermans HJ, DiSilvestro RA, Bray TM. Comparison of Zn and vitamin E for protection against hyperoxia induced lung damage. Free Radic Biol Med 1997;22:543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anttinen H, Oikarinen A, Puistola U, Paakko P, Ryhanen L. Prevention by zinc of rat lung collagen accumulation in carbon tetrachloride injury. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;132:536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klaassen CD, Liu J, Choudhuri S. Metallothionein: an intracellular protein to protect against cadmium toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1999;39:267–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campagne M, Thidodeaux H, van Bruggen N, Cairns B, Gerlai R, Palmer JT, Williams SP, Lowe DG. Evidence for a protective role of metallothionein-1 in focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:12870–12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carrasco J, Penkowa M, Hadberg H, Molinero A, Hidalgo J. Enhanced seizures and hippocampal neurodegeneration following kainic acidinduced seizures in metallothionein-I and II-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci 2000;12:2311–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma SK, Ebadi M. Metallothionein attenuates 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) induced oxidative stress in dopaminergic neurons. Antioxidant Redox Signal 2003;5:251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penkowa M, Quintana A, Carrasco J, Girlat M, Molinero A, Hildago J. Metallothionein prevents neurodegeneration and central nervous system cell death after treatment with gliotoxin 6-aminonicotinamide. J Neurosci Res 2004;77:35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penkowa M, Florit S, Giralt M, Quintana A, Molinero A, Carrasco J, Hidalgo J. Metallothionein reduces central nervous system inflammation, neurodegeneration, and cell death following kainic acid-induced epileptic seizures. J Neurosci Res 2004;79:522–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki JS, Nishimura N, Zhang B, Nakatsuru Y, Kobayashi S, Satoh M, Tohyama C. Metallothionein deficiency enhances skin carcinogenesis induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and 12-O-tetradecanolyphorbol-13-acetate in metallothionein null mice. Carcinogenesis 2003;24:1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang WH, Li LF, Zhang BX, Lu XY. Metallothionein null mice exhibit reduced tolerance to ultraviolet B injury in vivo. Exp Dermatol 2004;29:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fu K, Tomita T, Sarras MP, DeLisle RC, Andrews GK. Metallothionein protects against cerulein induced acute pancreatitis: analysis using transgenic mice. Pancreas 1998;17:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takano H, Satoh M, Shimada A, Sagai M, Yoshikawa T, Tohyama C. Cytoprotection by metallothionein against gastroduodenal mucosal injury caused by ethanol in mice. Lab Invest 2000;80:371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tran CD, Huynh H, van den Berg M, van der Pas M, Campell MA, Philcox JC, Coyle P, Rofe AM, Butler RN. Helicobacter-induced gastritis in mice not expressing metallothionein I and II. Helicobacter 2003;8:533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li X, Chen H, Epstein PN. Metallothionein protects islets from hypoxia and extends islet graft survival by scavenging most kinds of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 2004;279:765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oliver JR, Mara TW, Cherian MG. Impaired hepatic regeneration in metallothionein-I/II knockout mice after partial hepatectomy. Exp Biol Med 2005;230:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kang YJ, Chen Y, Yu A, Voss-McCowan M, Epstein PN. Overexpression of metallothionein in the heart of transgenic mice suppresses doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. J Clin Invest 1997;100:1501–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang GW, Schuschke DA, Kang YJ. Metallothionein overexpressing neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes are resistant to H2O2 toxicity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1999;276:H167–H175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kang YJ, Li G, Saari JT. Metallothionein inhibits ischemia reperfusion injury in mouse heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1999;276:H993–H997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang GW, Kang YJ. Inhibition of doxorubicin toxicity in cultured neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes with elevated metallothionein levels. J Pharm Exp Ther 1999;288:938–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang YJ, Li Y, Sun X, Sun X. Antiapoptotic effect and inhibition of ischemia reperfusion induced myocardial injury in metallothionein overexpressing transgenic mice. Am J Pathol 2003;163:1579–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takano H, Inoue K, Yanagisawa R, Sato M, Shimada A, Morita T, Sawada M, Nakamura K, Sanbongi C, Yoshikawa T. Protective role of metallothionein in acute lung injury induced by bacterial endotoxin. Thorax 2004;59:1057–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Inoue K-I, Takano H, Yanagisawa R, Sakurai M, Ichinose T, Sadakane K, Hiyoshi K, Sato M, Shimada A, Inoue M, et al. Role of metallothionein in antigen related airway inflammation. Exp Biol Med 2005;230:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pitt BR, Brookens MA, Steve AR, Atlas AB, Davies P, Kuo SM, Lazo JS. Expression of pulmonary metallothionein genes in late gestational lambs. Pediatr Res 1992;32:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hart BA, Cherian MG, Angel A. Cellular localization of metallothionein in the lung following repeated cadmium inhalation. Toxicology 1985;37:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bauman JW, Liu J, Liu YP, Klassen CD. Increase in metallothionein produced by chemicals that induce oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1991;110:347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Veness-Meehan KA, Cheng ERY, Mercier CE, Blixt SL, Johnston CJ, Watkins RH, Horowitz S. Cell-specific alterations in expression of hyperoxia-induced mRNAs of lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1991;5:516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wagenaar GT, ter Horst SA, van Gasten MA, Leijser LM, Mauad T, van der Velden PA, de Heer E, Hiemstra PS, Poorthuis BJ, Walther FJ. Gene expression profile and histopathology of experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia induced by prolonged oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;36:782–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yanagisawa R, Takano H, Inoue K, Ichinose T, Yoshida S, Sadakane K, Takeda K, Yoshino S, Yamaki K, Kumagai Y, et al. Complementary DNA microarray analysis in acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide and diesel exhaust particles. Exp Biol Med 2004;229:1081–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simon BA, Ye SQ, Easley RB, Lavoie T, Gregovey D, Garcia JGN. Microarray analysis of regional cellular responses to mechanical stress in canine ventilator associated lung injury (VALI). HOPGENE; Applied Genomics to Cardiopulmonary Disease. [2005.] Available from: www.hopkins-genoimcs.org/ali/ali009/100up.html. [Last accessed June 2005]

- 74.Gerhardinger C, Costa MB, Coulombe MC, Toth I, Hoehn T, Grosu P. Expression of acute-phase response proteins in retinal muller cells in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laframboise WA, Bombach KL, Dhir RJ, Muha N, Cullen RF, Pogozelski AR, Turk D, George JD, Guthrie RD, Magovern JA. Molecular dynamics of the compensatory response to myocardial infarct. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2005;38:103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson CJ, Stripp BR, Piedbeouf B, Wright TW, Mango GW, Reed CK, Finkelstein JN. Inflammatory and epithelial responses in mouse strains that differ in sensitivity to hyperoxic injury. Exp Lung Res 1998;24:189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hart BA, Voss GW, Shatos MA, Doherty J. Cross tolerance to hyperoxia following cadmium aerosol pretreatment. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1990;103:255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hart BA, Eneman JD, Gong Q, Durieux-Lu CG. Increased oxidant resistance of alveolar epithelial type II cells isolated from rats following repeated exposure to cadmium aerosols. Toxicol Lett 1985;81:131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hart BA, Gong Q, Eneman JD, Duieux-Lu CC, Kimberly P, Hacker MP. Increased oxidant resistance of alveolar macrophages isolated from rats repeatedly exposed to cadmium aerosols. Toxicology 1996;107:163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Courtade M, Carrera G, Paternain JL, Marel S, Carre PC, Folch J, Pipy B. Metallothoinein expression in human lung and its varying levels after lung transplantation. Chest 1998;113:371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pitt BR, Schwarz M, Woo ES, Yee E, Wasserloos K, Tran S, Weng W, Mannix RJ, Watkins SA, Tyurina YY, et al. Overexpression of metallothionein decreases sensitivity of pulmonary endothelial cells to oxidant injury. Am J Physiol 1997;273 (Lung Cell Mol Physiol 17):L856–L865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Nudelmann R, Stamler JS. S-nitrosylation: spectrum and specificity. Nat Cell Biol 2001;3:E1–E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jaffrey SR, Erdjumeni-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Temps P, Snyder SH. Protein nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol 2001;3:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kroncke KD, Fehsel K, Schmidt T, Zenke FT, Dasting I, Wesener JR, Betterman H, Breunig KD, Kolb-Bachofen V. Nitric oxide destroys zinc-sulfur clusters inducing zinc release from metallothionein and inhibition of the zinc finger-type yeast transcription activator LAC9. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994;200:1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berendji D, Kolb-Bachofen V, Zipfel PF, Skerka C, Carlberg C, Kroncke KD. Zinc finger transcription factors as molecular targets for nitric oxide-mediated immunosuppression: inhibtion of IL-2 gene expression in murine lymphocytes. Mol Med 1999;5:721–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kroncke KD. Zinc finger proteins as molecular targets for nitric oxide mediated gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2001;3:565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maret W. Zinc and sulfur: a critical biological partnership. Biochemistry 2004;43:3301–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tartler U, Kroncke KD, Meyer KL, Suschek CV, Kolb-Bachofen V. Nitric oxide interferes with islet cell zinc homeostasis. Nitric Oxide 2000;4:609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Spahl DU, Berendji-Grün D, Suschek CV, Kolb-Bachofen V, Kröncke, KD. Regulation of zinc homeostasis by inducible NO synthase-derived NO: nuclear metallothionein translocation and intranuclear Zn2+ release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:13952–13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fabisiak JP, Tyurin VA, Tyruina YY, Borisenko GG, Korotaeva A, Pitt BR, Lazo JS, Kagan VE. Redox regulation of copper-metallothionein. Arch Biochem Biophys 1999;363:171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu S-X, Kawai K, Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Borisenko GG, Fabisiak JP, Quinn PJ, Pitt BR, Kagan VE. Nitric oxide-dependent pro-oxidant and pro-apoptotic effect of metallothionein in HL-60 cells challenged with cupric nitrilotriacetate. Biochem J 2001;354:397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aravindakymar CT, Ceulemans J, DeLey M. Nitric oxide induces Zn2+ release from metallothionein by destroying zinc sulphur clusters without concomitant formation of S-nitrosothiol. Biochem J 1999;344:253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen Y, Irie Y, Keung WM, Maret W. S-nitrosothiols react preferentially with zinc thiolate clusters of metallothionein III through transnitrosation. Biochemistry 2002;41:8360–8367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.St. Croix CM, Stitt MS, Leelavanichkul K, Wasserloos KJ, Pitt BR, Watkins SC. Nitric oxide mediated signaling in endothelial cells as determined by spectral fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;15:785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tang ZL, Wasserloos K, Liu X, Reynolds IJ, Pitt BR, St. Croix CM. Roles for metallothionein and zinc in mediating the protective effects of nitric oxide on lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem 2002;234–235:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu S-X, Fabisiak JP, Tyurin VA, Borisenko GG, Pitt BR, Lazo JS, Kagan VE. Reconstitution of apo-superoxide dismutase by nitric oxide-induced copper transfer from metallothionein. Chem Res Toxicol 2000;13:922–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schwarz MA, Lazo JS, Yalowich JC, Allen WP, Whitmore M, Bergonia HA, Tzeng E, Billiar TR, Robbins PD, Lancaster JR Jr, et al. Metallothionein protects against the cytotoxic and DNA damaging effects of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:4452–4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Khatai L, Goessler W, Lorencova H, Zangger K. Modulation of nitric-oxide-mediated metal release from metallothionein by the redox state of glutathione in vitro. Eur J Biochem 2004;271:2408–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gow A, Ischiropoulos H. NO running on MT: regulation of zinc homeostasis by interaction of nitric oxide with metallothionein. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L183–L184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hibbs JBL, Taintor RR, Vavrin, Z. Macrophage cytotoxicity: role for L-arginine deiminase and imino nitrogen oxidation to nitrite. Science 1987;235:473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chung HT, Pae HO, Choi BM, Billiar TR, Kim YM. Nitric oxide as a bioregulator of apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001;282:1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mannick JB, Asano K, Izumi K, Kieff E, Stamler JS. Nitric oxide produced by human B lymphocytes inhibits apoptosis and Epstein Barr virus reactivation. Cell 1994;79:1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim YM, Bombeck CA, Billiar TR. Nitric oxide as a bifunctional regulator of apoptosis. Circ Res 1999;84:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim PK, Zamora R, Peterosko P, Billiar TR. The regulatory role of nitric oxide in apoptosis. Int Immunopharmacol 2001;1:1421–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim YM, de Vera ME, Watkins SC, Billiar TR. Nitric oxide protects cultured rat hepatocytes from TNFα-induced apoptosis by inducing heat shock protein 70 expression. J Biol Chem 1997;272:1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim YM, Talanian RV, Billiar TR. Nitric oxide inhibits apoptosis by preventing increases in caspase-3-like activity via two distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem 1997;272:31138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mannick JB, Hausladen A, Liu L, Hess DT, Zeng M, Miao QX, Kane LS, Gow AJ, Stamler JS. Fas-induced caspase denitrosylation. Science 1999;284:651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zamora R, Vodovotz Y, Aulak KS, Kim P, Kane JM, Alarcon L, Stuehr D, Billiar TRA. DNA mircoarray study of nitric oxide induced genes in mouse hepatocytes: implications for hepatic heme oxgyenase-I in ischemia/reperfusion. Nitric Oxide 2002;7:165–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ceneviva GD, Tzeng E, Hoyt DG, Yee E, Gallagher A, Englehardt JF, Kim Y-M, Billiar TR, Pitt BR. Nitric oxide inhibits lipopolysaccharide induced apoptosis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 1998;19:L717–L728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tzeng E, Shears LL, Robbins PD, Pitt BR, Geller D, Watkins SC, Simmons RL, Billiar TR. Vascular gene transfer of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene: characterization of activity and effects on myointimal hyperplasia. Mol Med 1996;2:211–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tzeng E, Kim Y-K, Pitt BR, Lizonova A, Kovesdi I, Billiar TR. Adenoviral transfer of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene blocks endothelial cell apoptosis. Surgery 1997;122:255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tzeng E, Billiar TR, Williams DL, Li J, Lizonova A, Kovesdi I, Kim Y-M. Adenoviral mediated iNOS gene transfer inhibits hepatocyte apoptosis. Surgery 1998;124:278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Steudal W, Watanabe M, Dirkranian K, Jacobson M, Jones RC. Expression of nitric oxide synthase isoforms (NOS II and NOS III) in adult rat lung in hyperoxic pulmonary hypertension. Cell Tissue Res 1999;295:317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Haddad IY, Pataki YG, Hu P, Galliani C, Beckman JS, Matalon S. Quantitation of nitrotyrosine levels in lung sections of animals and patients with acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 1994;94:2407–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gutierrez HH, Nieves B, Chumley P, Rivera A, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide regulation of superoxide-dependent rat lung injury: oxidant protective actions of endogenously produced and exogenously administered nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med 1996;21:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Howlett CE, Hutchinson JS, Veinot JP, Chiu A, Merchant P, Fliss H. Inhaled nitric oxide protects against hyeroixa induced apoptosis in rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 1999;277:L5960–L605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Garat C, Jayr C, Eddahibi S, Laffon M, Meignan M, Adnot S. Effects of inhaled nitric oxide or inhibition of endogenous nitric oxide formation on hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1957–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kobayashi H, Hataishi R, Mitsufuji H, Tanaka M, Jacobson M, Tomita T, Zapol WM, Jones RC. Antiinflammatory properties of inducible nitric oxide synthase in acute hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;24:390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhu S, Ware LB, Geiser T, Matthay MA, Matalon S. Increased levels of nitrate and surfactant protein A nitration in the pulmonary edema fluid of patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baron RM, Carvajal IM, Fredenbrugh LE, Liu X, Porrata Y, Cullivan ML, Haley KJ, Sonna LA, DeSanctis GT, Ingenito EP, et al. Nitric oxide synthase-2 down regulates surfactant protein B expression and enhances endotoxin induced lung injury in mice. FASEB J 2004;18:1276–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hardiman KM, McNicholas-Bevensee CM, Fortenberry J, Myles CT, Malik B, Eaton DC, Matalon S. Regulation of amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport by basal nitric oxide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Jilling T, Haddad IY, Cheng SH, Matalon S. Nitric oxide inhibits heterologous CFTR expression in polarized epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 1999;277:L89–L96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]