Abstract

The variety of pulmonary infections encountered in HIV-infected individuals indicates that many components of the host defense network are impaired. In addition to depletion of CD4+ T cell numbers, HIV infection results in functional deficits in CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and natural killer cells. Although some components of macrophage defense are preserved, lack of activation signals from CD4+ T cells contributes to impaired defense by macrophages. There are few data examining the functional capabilities of neutrophils in the lung, but evidence from peripheral blood neutrophils indicates that defense by these cells is also impaired. An improved understanding of these events in the lung during HIV infection could lead to specific interventions aimed at restoration of deficient function.

Keywords: HIV infections; macrophages, alveolar; neutrophils; opportunistic infections; T-lymphocytes

The variety of pulmonary infections encountered in HIV-infected individuals demonstrates that HIV impairs lung host defenses significantly (1). Although most investigations focus on HIV's effects on systemic immunity, a significant body of literature examines pulmonary immune mechanisms during HIV infection. In some instances, immune defects documented in the periphery are reflected in the lungs. In other instances, effects of HIV on lung cells differ from those in the periphery. This article focuses on the effects of HIV infection on pulmonary host defenses to explain why serious pulmonary infections remain common in this immunocompromised patient population.

The accessibility of lung cells for study by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) provides an opportunity to study the effects of HIV and opportunistic pathogens on lung host defenses. Once impairments in pulmonary host defense are understood, novel strategies to correct these defects may be developed for treatment and prophylaxis of pulmonary infections (1).

There are several general mechanisms by which HIV infection can impair pulmonary host defense; the literature documents alterations in cell numbers and in cell function. First, HIV directly infects and kills cells directed against pathogens, leaving decreased numbers of cells available to participate in host defense. Second, HIV infection induces qualitative defects in the metabolic and secretory functions of effector cells. Third, HIV-infected cells may shift their repertoires from elaboration of immunostimulating to immunosuppressive products. Fourth, HIV infection could interfere with the capacity of circulating lymphocytes, monocytes, or neutrophils to migrate into the lungs and to clear pathogens from the alveolar spaces. Finally, coinfection by a second pathogen can contribute to a breakdown in the host defense cascade.

HIV INFECTION OF LUNG CELLS

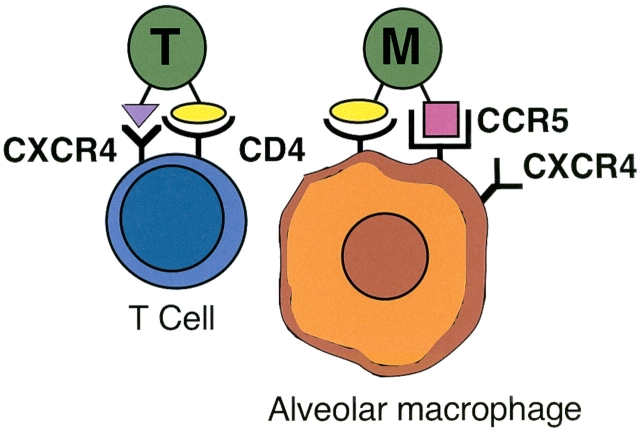

One important mechanism by which HIV alters lung host defense is by direct infection of pulmonary cells. Various HIV strains demonstrate tropism for lymphocytes or for monocytes/macrophages. The CD4 molecule, present on lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages, serves as the primary cellular receptor for HIV-1. In the lung, CD4 is the primary receptor for HIV on alveolar macrophages. Coreceptors are also needed for HIV entry into cells, and cellular coreceptors determine the tropism of HIV strains (Figure 1). Lymphocyte-tropic (T-tropic) strains interact with the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (fusin) to control entry into target cells. Infection with T-tropic strains can be blocked by the CXC chemokine SDF-1, which is a CXCR4 ligand.

Figure 1.

Tropism of HIV strains for lung cells. T-tropic strains infect T cells, using CD4 as the main receptor and CXCR4 as the coreceptor. M-tropic strains infect alveolar macrophages, using CCR5 as the coreceptor, although alveolar macrophages also express CXCR4.

In contrast, monocyte-tropic (M-tropic) strains interact with the chemokine receptor CCR5 to control entry into target cells. HIV infection of human alveolar macrophages is preferentially mediated by the CCR5 receptor, although alveolar macrophages also express CXCR4. Infection with M-tropic strains can be blocked with the CC chemokines RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β, which are CCR5 ligands. As HIV infection progresses, T-tropic virus replaces M-tropic virus, and this change is accompanied by more rapid immunologic decline.

Alveolar macrophages are a primary reservoir of HIV in the lung. HIV reverse transcriptase can be detected in alveolar macrophages obtained by lavage from patients with AIDS, and alveolar macrophages can be infected with HIV in vitro (2). Reports comparing the HIV burden of alveolar macrophages and peripheral blood monocytes are discrepant. The relative importance of in situ HIV replication in the lung, compared with the influx of previously infected cells from bone marrow and blood, is unclear. The percentages of alveolar macrophages expressing HIV antigens have varied considerably in reports from different laboratories (3). Detection of HIV by polymerase chain reaction suggests that HIV infection of alveolar macrophages is common (4). Alveolar macrophages become infected with increasing frequency as HIV infection progresses (5). When direct comparisons of alveolar macrophages and peripheral blood monocytes have been made, the data suggest that viral burdens in these two cell populations are equivalent (6).

How highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) modulates HIV replication in the lung and pulmonary host defense is unknown. Isolation of HIV from BAL in asymptomatic individuals decreases when CD4+ T cell counts are greater than 200/μl, and when patients receive HAART (7), suggesting a beneficial effect. However, HIV strains may evolve independently in the lung and blood, as phylogenetic analysis of BAL strains may differ from blood strains in HIV-infected individuals (8). Zidovudine resistance may differ in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and alveolar macrophages of single individuals, suggesting that HAART may have different effects on HIV in lung cells (9). Recent work comparing resistance patterns of peripheral blood and BAL cells demonstrates that resistant HIV genotypes in the lung may be most widely divergent in individuals exposed to combination antiretroviral therapy (10). Further studies are needed to examine the viral load in the lung during HAART and to determine how HAART modulates pulmonary host defenses (11).

ALTERATIONS IN LUNG CELL NUMBERS AND PHENOTYPES DURING HIV INFECTION

Most of the data describing alterations in lung cell numbers and phenotypes were obtained during bronchoscopies to diagnose pulmonary infections, making the effects of HIV and of opportunistic pathogens difficult to distinguish. Additionally, these studies were conducted before the availability of HAART. These studies revealed that lymphocyte percentages or concentrations are increased in BAL from HIV-infected individuals compared with uninfected individuals. Examination of BAL lymphocyte subsets from patients with AIDS shows decreases in CD4+ T cells and increases in CD8+ T cells. Therefore, CD4/CD8 ratios in BAL specimens may be lower than the ratios in peripheral blood. Some HIV-infected individuals may manifest pulmonary symptoms as a result of CD8+ T-cell influx into the lung, clinically diagnosed as lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis. Late in the course of HIV infection, numbers of CD8+ T cells decline. Depletion of CD8+ T cells may be associated with the development of disseminated cytomegalovirus and Mycobacterium avium infections (12). As in peripheral blood, most T cells in the lung bear αβ T-cell receptors on their surfaces, but a minority of T cells expresses γδ T-cell receptors. Numbers of γδ T cells are reported to be decreased or increased in HIV-infected patients with opportunistic infections.

Macrophage numbers in BAL from patients with AIDS are probably normal, but percentages are decreased by influx of other cells. Several BAL series have reported increases in the concentrations or in the percentages of neutrophils obtained from patients with AIDS compared with uninfected control subjects. Presumably, HAART results in the repopulation of pulmonary host defense cells as in blood, but BAL studies are not available to compare individuals receiving and not receiving HAART.

ALTERATIONS IN LYMPHOCYTE FUNCTION

CD4+ T Cells

Recent evidence demonstrates that, in addition to accelerated destruction of CD4+ T cells by HIV infection, production of T cells is also impaired. Underproduction can occur from infection-mediated death of progenitor cells and destruction of the hematopoietic stroma. In peripheral blood, T cells from patients with AIDS do not proliferate normally in response to mitogens. Even in patients with AIDS who show serologic evidence of prior infection with cytomegalovirus or herpes simplex virus, T cells fail to proliferate normally in response to these viral antigens. Failure to proliferate may be caused in part by impaired elaboration of IL-2. Peripheral blood T cells from patients with AIDS have impaired IL-2 secretion in response to a variety of stimuli. In vitro, recombinant IL-2 can restore some mitogenic responses of blood T cells in patients with AIDS (13). Clinical trials of IL-2 for HIV infection demonstrate that IL-2 increases CD4+ T cell counts in recipients without increasing HIV replication, particularly when given intermittently (14). IL-16 may prime mature CD4+ memory cells to respond to IL-2, and decreased IL-16 levels correlate with HIV progression. Therefore, IL-16 therapy may be useful in addition to IL-2 to restore CD4+ T-cell responses (15).

T cells from HIV-infected individuals do not produce IFN-γ normally in response to mitogens or antigens. The relative ability of peripheral lymphocytes to elaborate IFN-γ correlates with clinical status and CD4+ T cell count and predicts progression to AIDS (16). Experimental work suggests that progression from asymptomatic HIV infection to AIDS is accompanied by a switch from Th1-like responses to Th2-like responses. In theory, prevention of this switch in T-cell responses could prevent progression to AIDS. IL-12, a cytokine that favors Th1 development and inhibits Th2 development, has been shown to restore cell-mediated immunity in T cells obtained from HIV-infected individuals (17). Few data exist on the functional capabilities of lung CD4+ cells.

CD8+ T Cells

As with CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells in blood and lung can be infected with HIV. HIV infection also impairs the functional capacities of CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cells obtained from the lungs of HIV-infected individuals do not lyse appropriate targets in vitro (18). For example, CD8+ T cell–mediated cytotoxicity for influenza virus is decreased in HIV-infected individuals (19). Phenotypically, CD8+ T cells from patients with AIDS show increased expression of activation markers, compared with uninfected individuals, and increased percentages of activated cells predict progression of HIV-related disease. Peripheral CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected individuals may be poor effectors because they lack required maturation signals (20). An analogous situation likely exists in the lung.

CD8+ T-cell alveolitis occurs during HIV infection, but the functional capabilities of these cells and their intended targets require further investigation. Subpopulations of CD8+ T cells, obtained from HIV-infected individuals, are cytotoxic for macrophages or B-cell lines expressing HIV antigens (21). The intensity of CD8+ alveolitis correlates with HIV load, and the poor prognosis associated with alveolitis may be a result of the elevated viral burden (22). Unlike the periphery, local concentrations of IL-2 and IFN-γ may be increased in the lung during HIV infection due to activation of CD8+ T cells (23). The alveolitis may be driven by overproduction of IL-15, a cytokine with IL-2–like effects, by alveolar macrophages. Alveolar macrophages from HIV-infected individuals produce large quantities of IL-15, which enhances antigen presentation by alveolar macrophages and causes proliferation of lung CD8+ T cells (24).

NK Cells

Increased numbers of NK cells in BAL have been observed in HIV-infected individuals, but with progressive HIV disease, they lose functional capabilities. NK cells may be nonfunctional in HIV infection because they are dependent on signals from CD4+ T cells for optimal function (25). Biologic response modifiers such as recombinant IL-2 restore lytic ability in vitro (26), and IFN-γ may augment NK cell activity in early stages of HIV infection (27).

B Cells

Analysis of peripheral B cells from HIV-infected individuals shows elevated numbers of cells that spontaneously secrete immunoglobulins, and patients with AIDS have increases in serum IgA, IgG, and IgM. The IgG increase is predominantly due to IgG subtypes IgG1 and IgG3, with decreases in IgG2 and IgG4. Antibody to polysaccharides in bacterial cell walls is composed of IgG2, and patients with AIDS who have pyogenic infections have lower serum IgG2 than patients without bacterial disease. Concentrations of immunoglobulins in the lung may depend on the stage of HIV infection or the presence of pulmonary pathogens. Compared with uninfected individuals, measurement of immunoglobulins in BAL from patients with AIDS who have pulmonary symptoms shows increases in total amounts of IgG, IgM, and IgA. Local immunoglobulin synthesis may occur in the lung, as shown by increased numbers of IgG-, IgM-, and IgA-secreting cells (28). However, BAL from asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals contains decreased concentrations of IgG compared with uninfected control subjects (29). During HAART, IgG levels in asymptomatic, HIV-infected individuals are increased compared with uninfected volunteers (30).

Antibody responses to specific antigens are impaired in HIV-infected individuals. B-cell abnormalities begin early in HIV infection, with failure to produce antibody in response to mitogen at the time of HIV seroconversion, before T-cell function is affected. B cells from patients with AIDS show impaired proliferation in response to mitogens and do not initiate normal antibody synthesis in response to newly encountered antigens. Decreased IgG concentrations in the lung may be a result of impaired ability of alveolar macrophages to induce IgG secretion from B cells, likely as a result of transforming growth factor-β secretion (29).

ALTERATIONS IN MACROPHAGE FUNCTION

Phagocytosis, Respiratory Burst, and Killing of Organisms

Peripheral blood monocytes from patients with AIDS are reported by some investigators to be defective in chemotaxis to several chemoattractants, but other investigators find unimpaired chemotaxis. Alveolar macrophages from asymptomatic, HIV-infected subjects demonstrate enhanced phagocytosis for Staphylococcus aureus (31). BAL cells from HIV-infected individuals demonstrate increased fungistatic activity against Cryptococcus neoformans compared with cells from uninfected control subjects (32). The magnitude of the respiratory burst of alveolar macrophages from patients with AIDS in vitro is not different from uninfected control subjects, and IFN-γ enhances the response in cells from both groups equivalently (33). Alveolar macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages do not kill Toxoplasma gondii or Chlamydia psittaci, whether obtained from patients with AIDS or from uninfected individuals (33). When exposed in vitro to IFN-γ, alveolar macrophages obtained from patients with AIDS increase their killing of these organisms in a manner equivalent to uninfected individuals' cells (33). In contrast, HIV infection may impair phagocytosis of organisms that commonly cause pulmonary infections in susceptible individuals. For example, alveolar macrophages from HIV-infected individuals demonstrate decreased binding and phagocytosis of Pneumocystis in vitro, and this defect correlates with decreased expression of alveolar macrophage mannose receptors (34).

Antigen Presentation

During HIV infection, blood monocytes do not present antigens to T cells normally (35). In comparison to blood monocytes, alveolar macrophages are considered to be relatively poor antigen-presenting cells. However, alveolar macrophages from HIV-infected patients have enhanced ability to present antigen compared with alveolar macrophages from uninfected control subjects (36). Dendritic cells are also important antigen-presenting cells in the lung. HIV infection of dendritic cells is cytopathic for these cells, and the numbers of dendritic cells are decreased in asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals and in patients with AIDS (37). Dendritic cells from HIV-infected individuals exhibit defective antigen presentation and may facilitate HIV infection of T cells (38).

Tumor Necrosis Factor Elaboration

Some patients with AIDS are reported to have elevated serum levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF). When peripheral blood monocytes are examined, they are reported to have high spontaneous release of TNF (39) or suboptimal release after appropriate stimulation (40). Other investigators have found that HIV infection of monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro does not induce TNF release (41). Alveolar macrophages from asymptomatic, HIV-seropositive individuals have increased spontaneous TNF release, which correlates with extent of HIV expression (42). BAL cells from smokers release less TNF than BAL cells from nonsmokers, suggesting that smoking and HIV interact to suppress macrophage function (43). In the lung, TNF decreases HIV replication in alveolar macrophages by inducing production of RANTES and by decreasing CCR5 expression (44).

ALTERATIONS IN NEUTROPHIL FUNCTION

Although patients with AIDS may have increased numbers of neutrophils at the time of BAL, little is known about the host defense capabilities of these cells. In several studies, peripheral neutrophils from some patients with AIDS who had frequent localized infections showed decreased chemotaxis in vitro. Neutrophils from HIV-infected individuals have decreased expression of CD88, the ligand for C5a, which could contribute to increased susceptibility to bacterial infections (45). Recently, pulmonary neutrophils from HIV-infected individuals have been shown to express decreased immunoglobulin G Fc-γ receptor 1 expression compared with neutrophils from uninfected volunteers (46).

The phagocytic capacity of neutrophils during HIV infection is controversial and may depend on the stage and severity of HIV infection. For example, neutrophils from individuals with early HIV infection demonstrate enhanced phagocytosis (47). Phagocytosis of opsonized S. aureus is decreased in the peripheral blood neutrophils of some, but not all, patients with AIDS (48). The defect in phagocytosis can be corrected by in vivo administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (49). Other investigators find decreased phagocytosis and intracellular killing of Candida albicans by neutrophils obtained from intravenous drug-using patients with AIDS, whereas cells from homosexual AIDS patients function normally (50). The authors postulate that these defects are associated with intravenous drug use rather than HIV infection because cells from seronegative intravenous drug users were also abnormal.

The neutrophil possesses potent oxygen-dependent mechanisms to kill intracellular organisms. Peripheral neutrophils from patients with AIDS are reported to produce subnormal, normal, or supernormal amounts of superoxide when stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate. The ability of pulmonary neutrophils from HIV-infected individuals to produce superoxide is unknown.

CONCLUSION

HIV infection impairs many aspects of host defense in the lung and in the periphery. In addition to depletion of CD4+ T cell numbers, HIV results in functional deficits in CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells. Although some components of macrophage defense are preserved, lack of activation signals from CD4+ T cells contributes to impaired defense by macrophages. There are few data examining the functional capabilities of neutrophils in the lung, but evidence from peripheral blood neutrophils indicates that defense by these cells is also impaired. An improved understanding of these events in the lung during HIV infection can lead to specific interventions aimed at restoration of deficient function.

Supported in part by a Merit Review Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs and R01 HL08342 from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Statement: J.M.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Beck JM, Rosen MJ, Peavy HH. Pulmonary complications of HIV infection: report of the fourth NHLBI workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:2120–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salahuddin SZ, Rose RM, Groopman JE, Markham PD, Gallo RC. Human T lymphotropic virus type III infection of human alveolar macrophages. Blood 1986;68:281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agostini C, Trentin L, Zambello R, Semenzato G. HIV-1 and the lung: infectivity, pathogenic mechanisms and cellular immune responses taking place in the lower respiratory tract. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;147:1038–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose RM, Krivine A, Pinkston P, Gillis JM, Huang A, Hammer SM. Frequent identification of HIV-1 DNA in bronchoalveolar lavage cells obtained from individuals with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143:850–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sierra-Madero JG, Toossi Z, Hom DL, Finegan CK, Hoenig E, Rich EA. Relationship between load of virus in alveolar macrophages from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons, production of cytokines, and clinical status. J Infect Dis 1994;169:18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewin SR, Kirihara J, Sonza S, Irving L, Mills J, Crowe SM. HIV-1 DNA and mRNA concentrations are similar in peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages in HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS 1998;12:719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood KL, Chaiyarit P, Day RB, Wang Y, Schnizlein-Bick CT, Gregory RL, Twigg HL III. Measurements of HIV viral loads from different levels of the respiratory tract. Chest 2003;124:536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itescu S, Simonelli PF, Winchester RJ, Ginsberg HS. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains in the lungs of infected individuals evolve independently from those in peripheral blood and are highly conserved in the C-terminal region of the envelope V3 loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:11378–11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gates A, Coker RJ, Miller RF, Williamson JD, Clarke JR. Zidovudine-resistant variants of HIV-1 in the lung. AIDS 1997;11:702–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White NC, Israël-Biet D, Coker RJ, Mitchell DM, Weber JN, Clarke JR. Different resistance mutations can be detected simultaneously in the blood and the lung of HIV-1 infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy. J Med Virol 2004;72:325–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White NC, Agostini C, Israël-Biet D, Semenzato G, Clarke JR. The growth and the control of human immunodeficiency virus in the lung: implications for highly active antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Clin Invest 1999;29:964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiala M, Herman V, Gornbein J. Role of CD8+ in late opportunistic infections of patients with AIDS. Res Immunol 1992;143:903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheridan JF, Aurelian L, Donnenberg AD, Quinn TC. Cell-mediated immunity to cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) antigens in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: interleukin-1 and interleukin-2 modify in vitro responses. J Clin Immunol 1984;4:304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sereti I, Lane HC. Immunopathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus: implications for immune-based therapies. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1738–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center DM, Kornfeld H, Ryan TC, Cruikshank WW. Interleukin 16: implications for CD4 functions and HIV-1 progression. Immunol Today 2000;21:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray HW, Hillman JK, Rubin BY, Kelly CD, Jacobs JL, Tyler LW, Donelly DM, Carriero SM, Godbold JH, Roberts RB. Patients at risk for AIDS-related opportunistic infections: clinical manifestations and impaired gamma interferon production. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1504–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clerici M, Lucey DR, Berzofsky JA, Pinto LA, Wynn TA, Blatt SP, Dolan MJ, Hendrix CW, Wolf SF, Shearer GM. Restoration of HIV-specific cell-mediated immune responses by interleukin-12 in vitro. Science 1993;262:1721–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Semenzato G. Immunology of interstitial lung diseases: cellular events taking place in the lung of sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis and HIV infection. Eur Respir J 1991;4:94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shearer GM, Bernstein DC, Tung KSK, Via CS, Redfield R, Salahuddin SZ, Gallo RC. A model for the selective loss of major histocompatibility complex self-restricted T cell immune response during the development of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). J Immunol 1986;137:2514–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman J, Shankar P, Manjanath N, Andersson J. Dressed to kill? A review of why antiviral CD8 T lymphocytes fail to prevent progressive immunodeficiency in HIV-1 infection. Blood 2001;98:1667–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Autran B, Plata F, Guillon JM, Joly P, Mayaud C, Debré P. HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed against alveolar macrophages in HIV-infected patients. Res Virol 1990;141:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Twigg HL, Soliman DM, Day RB, Knox KS, Anderson RJ, Wilkes DS, Schnizlein-Bick CT. Lymphocytic alveolitis, bronchoalveolar lavage viral load, and outcome in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1439–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twigg HL III, Spain BA, Soliman DM, Knox K, Sidner RA, Schnizlein-Bick C, Wilkes DS, Iwamoto GK. Production of interferon-gamma by lung lymphocytes in HIV-infected individuals. Am J Physiol 1999;276:L256–L262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agostini C, Zambello R, Facco M, Perin A, Piazza F, Siviero M, Basso U, Bortolin M, Trentin L, Semenzato G. CD8 T-cell infiltration in extravascular tissues of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: interleukin-15 upmodulates costimulatory pathways involved in the antigen-presenting cells-T-cell interaction. Blood 1999;93:1277–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agostini C, Poletti V, Zambello R, Trentin L, Siviero F, Spiga L, Gritti F, Semenzato G. Phenotypical and functional analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage lymphocytes in patients with HIV infection. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;138:1609–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agostini C, Zambello R, Trentin L, Feruglio C, Masciarelli M, Siviero F, Poletti V, Spiga L, Gritti F, Semenzato G. Cytotoxic events taking place in the lung of patients with HIV-1 infection: evidence of an intrinsic defect of the major histocompatibility complex-unrestricted killing partially restored by the incubation with rIL-2. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poli G, Introna M, Zanaboni F, Peri G, Carbonari M, Aiuti F, Lazzarin A, Moroni M, Mantovani A. Natural killer cells in intravenous drug abusers with lymphadenopathy syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 1985;62:128–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rankin JA, Walzer PD, Dwyer JM, Schrader CE, Enriquez RE, Merrill WW. Immunologic alterations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Am Rev Respir Dis 1983;128:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Twigg HL III, Spain BA, Soliman DM, Bowen LK, Heidler KM, Wilkes DS. Impaired IgG production in the lungs of HIV-infected individuals. Cell Immunol 1996;170:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fahy RJ, Diaz PT, Hart J, Wewers MD. BAL and serum IgG levels in healthy asymptomatic HIV-infected patients. Chest 2001;119:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musher DM, Watson DA, Nickeson D, Gyorkey F, Lahart C, Rossen RD. The effect of HIV infection on phagocytosis and killing of Staphylococcus aureus by human pulmonary alveolar macrophages. Am J Med 1990;299:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reardon CC, Kim SJ, Wagner RP, Koziel H, Kornfeld H. Phagocytosis and growth inhibition of Cryptococcus neoformans by human alveolar macrophages: effects of HIV-1 infection. AIDS 1996;10:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray HW, Gellene RA, Libby DM, Rothermel CD, Rubin BY. Activation of tissue macrophages from AIDS patients: in vitro response of AIDS alveolar macrophages to lymphokines and interferon-γ. J Immunol 1985;135:2374–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koziel H, Eichbaum Q, Kruskal BA, Pinkston P, Rogers RA, Armstrong MY, Richards FF, Rose RM, Ezekowitz RA. Reduced binding and phagocytosis of Pneumocystis carinii by alveolar macrophages from persons infected with HIV-1 correlates with mannose receptor downregulation. J Clin Invest 1998;102:1332–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rich EA, Toossi Z, Fujiwara H, Hanigosky R, Lederman MM, Ellner JJ. Defective accessory function of monocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-related disease syndromes. J Lab Clin Med 1988;112:174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twigg HL III, Lipscomb MF, Yoffe B, Barbaro DJ, Weissler JC. Enhanced accessory cell function by alveolar macrophages from patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: potential role for depletion of CD4+ cells in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1989;1:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macatonia SE, Lau R, Patterson S, Pinching AJ, Knight SC. Dendritic cell infection, depletion and dysfunction in HIV-infected individuals. Immunology 1990;71:38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spiegel H, Herbst H, Niedobitek G, Foss HD, Stein H. Follicular dendritic cells are a major reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in lymphoid tissues facilitating infection of CD4+ T-helper cells. Am J Pathol 1992;140:15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright SC, Jewett A, Mitsuyasu R, Bonavida B. Spontaneous cytotoxicity and tumor necrosis factor production by peripheral blood monocytes from AIDS patients. J Immunol 1988;141:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ammann AJ, Palladino MA, Volberding P, Abrams D, Martin NL, Conant M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and beta in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. J Clin Immunol 1987;7:481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munis JR, Richman DD, Kornbluth RS. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of macrophages in vitro neither induces tumor necrosis factor (TNF)/cachectin gene expression nor alters TNF/cachectin induction by lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest 1990;85:591–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agostini C, Zambello R, Trentin L, Garbisa S, Di Cella PF, Bulian P, Onisto M, Poletti V, Spiga L, Raise E, et al. Alveolar macrophages from patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex constitutively synthesize and release tumor necrosis factor alpha. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wewers MD, Diaz PT, Wewers ME, Lowe MP, Nagaraja HN, Clanton TL. Cigarette smoking in HIV infection induces a suppressive inflammatory environment in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1543–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lane BR, Markovitz DM, Woodford NL, Rochford R, Strieter RM, Coffey MJ. TNF-alpha inhibits HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages by inducing the production of RANTES and decreasing C–C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) expression. J Immunol 1999;163:3653–3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meddows-Taylor S, Pendle S, Tiemessen CT. Altered expression of CD88 and associated impairment of complement 5a-induced neutrophil responses in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients with and without pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2001;183:662–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armbruster C, Krugluger W, Huber M, Stephan K. Immunoglobulin G Fc(gamma) receptor expression on polymorphonuclear cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of HIV-infected and HIV-seronegative patients with bacterial pneumonia. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004;42:192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bandres JC, Trial J, Musher DM, Rossen RD. Increased phagocytosis and generation of reactive oxygen products by neutrophils and monocytes of men with stage 1 human immunodeficiency virus infections. J Infect Dis 1993;168:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baldwin GC, Gasson JC, Quan SG, Fleischmann J, Weisbart R, Oette D, Mitsuyasu RT, Golde DW. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor enhances neutrophil function in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988;85:2763–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Pizzo PA, Rubin M. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances the phagocytic and bactericidal activity of normal and defective human neutrophils. J Infect Dis 1991;163:579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lazzarin A, Uberti Foppa C, Galli M, Mantovani A, Poli G, Franzetti F, Novati R. Impairment of polymorphonuclear leucocyte function in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and with lymphadenopathy syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 1986;65:105–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]