Abstract

The mitochondrion of the parasitic protozoon Trypanosoma brucei does not encode any tRNAs. This deficiency is compensated for by partial import of nearly all of its cytosolic tRNAs. Most trypanosomal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are encoded by single copy genes, suggesting the use of the same enzyme in the cytosol and in the mitochondrion. However, the T. brucei genome encodes two distinct genes for eukaryotic aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS), although the cell has a single tRNAAsp isoacceptor only. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the two T. brucei AspRSs evolved from a duplication early in kinetoplastid evolution and also revealed that eight other major duplications of AspRS occurred in the eukaryotic domain. RNA interference analysis established that both Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 are essential for growth and required for cytosolic and mitochondrial Asp-tRNAAsp formation, respectively. In vitro charging assays demonstrated that the mitochondrial Tb-AspRS2 aminoacylates both cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAAsp, whereas the cytosolic Tb-AspRS1 selectively recognizes cytosolic but not mitochondrial tRNAAsp. This indicates that cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAAsp, although derived from the same nuclear gene, are physically different, most likely due to a mitochondria-specific nucleotide modification. Mitochondrial Tb-AspRS2 defines a novel group of eukaryotic AspRSs with an expanded substrate specificity that are restricted to trypanosomatids and therefore may be exploited as a novel drug target.

In most animal and fungal mitochondria, the total set of tRNAs required for translation is encoded on the mitochondrial genome and thus of bacterial evolutionary origin. The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs)2 responsible for charging of mitochondrial tRNAs are always nuclear encoded and need to be imported into mitochondria. We therefore expect to find two sets of aaRSs, one for cytosolic aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis and a second one, of bacterial evolutionary origin, for aminoacylation of mitochondrial tRNAs (1, 2).

In most cells, however, some aaRSs are targeted to both the cytosol as well as to mitochondria (3). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for example, four aaRSs are double-targeted to both compartments, indicating that they are able to aminoacylate tRNAs of both eukaryotic and bacterial evolutionary origin (4–6). In plants, the situation is more complex, since protein synthesis occurs in three compartments: the cytosol, the mitochondria, and the plastids. A recent analysis in Arabidopsis has shown that, rather than having three unique sets of aaRSs specific for the three translation systems, more than 15 aaRSs were dually targeted to the mitochondria and the plastid (7). Moreover, there is at least one aaRS that is shared between all three compartments. In summary, these examples indicate that the overlap between the different sets of aaRSs used in the various translation systems is variable and can be extensive.

Most eukaryotes, except many animals and fungi, lack a variable number of mitochondrial tRNA genes. Mitochondrial translation in these organisms depends on import of a small fraction of the corresponding nucleus-encoded cytosolic tRNAs (8–10). As a consequence, imported tRNAs are always of eukaryotic evolutionary origin. An intriguing situation is found in trypanosomatids (such as Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania spp.), where all mitochondrial tRNA genes have apparently been lost and all mitochondrial tRNAs are imported from the cytosol. In these organisms, all mitochondrial tRNAs derive from cytosolic tRNAs (11). It is therefore reasonable to assume that trypanosomal aaRSs are dually targeted to the cytosol and the mitochondrion. For the T. brucei glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS) and the glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, the dual localization has been shown experimentally (12). Moreover, dual targeting of essentially all aaRSs is suggested by the fact that the genome of T. brucei and other trypanosomatids encodes only 23 distinct aaRSs, fewer than any other eukaryote that has a mitochondrial translation system (13). Unexpectedly, two distinct genes were found for the tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS), the lysyl-tRNA synthetase and the aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS). A recent study has shown that the two trypanosomal TrpRSs are required for cytosolic and mitochondrial tryptophanyl-tRNA formation (14). Trypanosomal tRNATrp is imported to the mitochondria, where it undergoes C to U editing at the wobble nucleotide and is thiolated at position 33. The RNA editing is required to decode the reassigned mitochondrial tryptophan codon UGA (14–16). Both nucleotide modifications are antideterminants for the cytosolic TrpRS (14). As we concluded previously (14), the presence of a second TrpRS with expanded substrate specificity is required to efficiently aminoacylate imported, mature tRNATrp in trypanosomal mitochondria.

The present study focuses on the characterization and functional analysis of another pair of duplicated trypanosomal aaRSs, the AspRSs. We show that the two enzymes are individually essential for normal growth of insect stage T. brucei. We also demonstrate that the two trypanosomal AspRSs are of eukaryotic evolutionary origin and that the aminoacylation of the cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAAsp species requires these two distinct AspRSs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Phylogenetic Analyses

Sequences were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant data base and the Integrated Microbial Genomes data base (17), and structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (18). Structure-based alignment was completed using the Multiseq 2.0 module in VMD 1.8.5 (19) and performed as described (20). The sequences were split into four subgroups (eukaryotic AspRSs, archaeal AspRSs, asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase, and bacterial/mitochondrial AspRSs), and each sequence group was aligned separately with the program MUSCLE (21). In a similar fashion as detailed previously (20), the subgroups were then aligned on the bases of a structural superposition and derived structure-based alignment of the solved AspRS crystal structures. Phylogenetic calculation began with an initial neighbor-joining tree (BIONJ) computed with the program PHYML version 3.0.1 (22). In the computation of the starting tree and in the subsequent maximum likelihood optimization of branch lengths, tree topology, and rate parameters, the JTT + Γ model of amino acid substitution was used with four evolutionary rate categories, and other parameters were computed from maximum likelihood estimates. The maximum likelihood tree search was performed with the subtree pruning and regrafting (SPR) algorithm in PHYML. Bootstrap analysis is from the Shimodaira-Hasegawa re-estimation of log likelihood local bootstrap proportions calculation implemented in PHYML.

Cells

Procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 (23) was grown in SDM-79 supplemented with 15% FCS, 25 μg/ml hygromycin, 15 μg/ml G-418 at 27 °C, and harvested at 1.5–3.5 × 107 cells/ml.

Production of Transgenic Cell Lines

As a tag to analyze the localization of Tb-AspRS1 (accession number Tb927.6.1880) and Tb-AspRS2 (accession number Tb10.70.6800), we used a 10-amino acid epitope of the major structural protein of yeast Ty1, which is recognized by the monoclonal antibody BB2 (24). The sequences corresponding to the carboxyl-terminal Ty1-tagged Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 were cloned into a derivative of pLew-100 (23) to allow tetracycline-inducible expression of the tagged proteins.

RNAi of Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspS2 was performed by using stem loop constructs containing the puromycin resistance gene. As inserts, we used a 409-bp fragment (nucleotides 313−721) of the Tb-AspRS1 gene and a 515-bp fragment (nucleotides 3−517) of the Tb-AspRS2 gene.

Transfection of T. brucei and selection with antibiotics, cloning, and induction with tetracycline were done as described in Ref. 25.

Cell Fractionation by Digitonin

Fractionation of Ty1 epitope-tagged Tb-AspRS1- and Tb-AspRS2-expressing cells was done as previously described (14).

Cloning, Overexpression, and Purification of Tb-AspRS1

The gene was PCR-amplified using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche Applied Science). Tb-AspRS1 was cloned into NcoI/BamHI in pET15b (Novagen), which encodes an NH2-terminal His tag. After sequence verification, the resulting plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL-21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene). Cells were grown at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml) and protein expression was autoinduced using the Overnight Express Autoinduction System (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After harvest, the cells were sonicated, and the protein was purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The desired fractions were pooled, dialyzed against 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 50% glycerol, and stored at −20 °C.

Preparation of RNA-free Cytosolic Fractions

Washed T. brucei (3 × 1010 cells) were lysed in 12 ml of SoTE buffer (0.6 m sorbitol, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 2 mm EDTA) by nitrogen cavitation (80 bars, 40 min). The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and supplemented with 25 mm KCl, 8 mm MgCl2, and 150 mm NaCl and subjected to ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 15 min at 4 °C). The resulting supernatant was applied on a DEAE-Sepharose column (1.7-ml bed volume) equilibrated in acylation buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 8 mm MgCl2, 25 mm KCl) containing 0.6 m sorbitol and 150 mm NaCl in order to remove the cytosolic tRNA. Approximately 4 ml of the flow-through fraction was collected and loaded onto a Sephadex G-100 column (25-ml bed volume; 25-cm length) equilibrated in acylation buffer. The column was developed in acylation buffer, and 10 fractions (4 ml each) were collected. Finally 100% glycerol (one-ninth volume) and dithiothreitol (to 5 mm) were added to the combined peak fractions (fractions 2 and 3). The resulting samples were aliquoted, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −70 °C.

Preparation of Mitochondrial Matrix Fractions

Mitoplasts were isolated as described previously (26). An aliquot containing 1.5 mg of mitoplast proteins was centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 6800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in acylation buffer (see above) containing 1% CHAPS. The resulting suspension was centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4 °C at a full 21,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was used as a source of enzyme in the in vitro aminoacylation reactions.

In Vitro Aminoacylation Assay

The charging assays were performed as described in Ref. 14. The substrate amino acids used were a mixture of 77 μm unlabeled and 3 μm [3H]aspartate (specific activity of stock solution: 32 Ci/mmol) or, as a control, 456 μm [14C]glutamine (specific activity of stock solution: 200 mCi/mmol). RNA-free cytosol or mitochondrial matrix extracts were used at 1:25 and 1:2.5 ratios of the total reaction volume, respectively. Native cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAs were extracted as described (14) and used at 0.6 and 1 μg/μl, respectively. At these concentrations, the amount of tRNAAsp in both fractions was identical, as determined by Northern analysis (data not shown). The aminoacylation reactions using recombinant Tb-AspRS1 were performed as described above except that 70 nm recombinant Tb-AspRS1 was used as a source of enzyme.

ATP Production Assays

ATP production assays were done as described in Ref. 27.

RESULTS

The T. brucei Genome Encodes Two Eukaryotic AspRSs

Unlike for most other aaRSs, the T. brucei genome encodes open reading frames for two putative AspRS homologs. The proteins have predicted molecular masses of 62.9 kDa (Tb-AspRS1; accession number Tb927.6.1880) and 60.8 kDa (Tb-AspRS2; accession number Tb10.70.6800). Bioinformatic analysis predicts a weak mitochondrial targeting signal for Tb-AspRS2. Tb-AspRS1 appears to be the ortholog of the cytosolic AspRS of other eukaryotes with which it shares 43–49% of sequence identity. Tb-AspRS2, on the other hand, is more similar to Tb-AspRS1 (43% of sequence identity) rather than to other cytosolic AspRSs (34–38% of sequence identity) of eukaryotes.

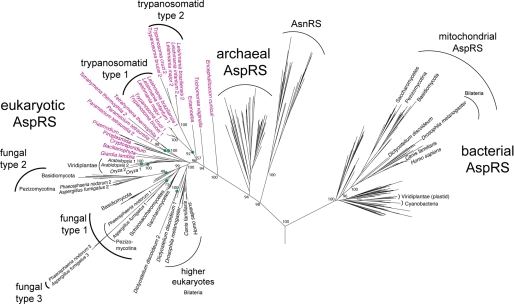

In order to investigate the relationship between the two trypanosomal AspRSs more precisely, we performed a detailed phylogenetic analysis of AspRSs from all three domains of life (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. 1). Nonplant eukaryotes are expected to have two distinct AspRSs, a cytosolic one of eukaryotic evolutionary origin and a mitochondrial one of bacterial descent. As is evident in the phylogeny in Fig. 1, most higher eukaryotes, fungi, and even slime mold follow this pattern. These organisms encode one AspRS that clusters with other eukaryotes on the archaeal-eukaryotic side of the tree, whereas the second (mitochondrial) AspRS groups with the bacterial AspRSs. In T. brucei and other trypanosomatids, there are also two AspRS, but both are of eukaryotic origin, resulting from a gene duplication event along the trypanosomatid line of descent (Fig. 1). Moreover, our analysis revealed eight other major duplications of eukaryotic AspRS in different taxons (see “Discussion”). Trypanosomatids lack a bacterial type AspRS. The same is true for many lower eukaryotes (Fig. 1, shown in red). This is no surprise, since this group includes genera (e.g. Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Entamoeba, and Encephalitozoon) that have mitosomes or hydrogenosomes (e.g. Trichomonas), which lack genomes and therefore do not require organellar aminacylation (28). Moreover, the genera in this group that have bona fide mitochondria (Plasmodium, Paramecium, and Tetrahymena) import most or even all of their mitochondrial tRNAs from the cytosol. Although Plasmodium encodes only a single AspRS, which must be dually targeted to cytosol and mitochondrion, separate AspRS duplications took place in the Paramecium and Tetrahymena lineages, resulting in two copies of the eukaryotic type AspRS in these organisms. It is plausible that, as is shown here for the trypanosomal AspRSs, one of the enzymes has adapted to function in mitochondria.

FIGURE 1.

A maximum likelihood phylogeny of AspRS sequences from all domains of life. The eukaryotic portion is shown in greater detail to show eight independent duplication events (at nodes marked by green circles) and other relationships described throughout. Species names colored purple highlight the eukaryotes that lack a bacterial type mitochondrial AspRS. Bootstrap proportions show statistical support for major branches and for those groups referred to under “Discussion.” A fully detailed tree, including all bootstrap values and species names, is displayed in supplemental Fig. 1.

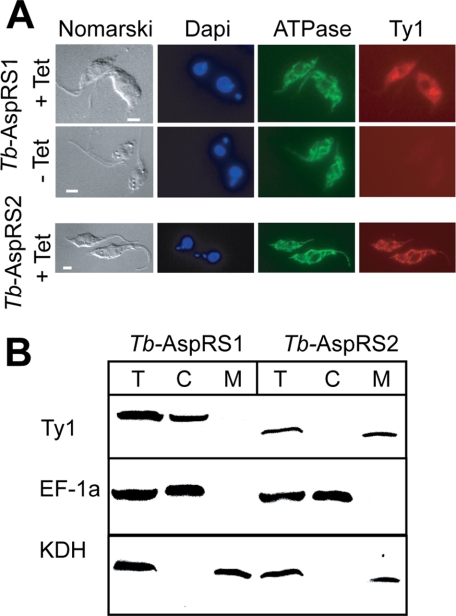

Intracellular Localization of Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2

In order to determine the localization of the two enzymes, we prepared transgenic cell lines allowing inducible expression of Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 versions carrying the 10-amino acid-long Ty1 peptide at their carboxyl termini (24). Immunofluorescence analysis using an anti-Ty1 antibody showed a tetracycline-inducible diffuse staining of the tagged Tb-AspRS1 consistent with a cytosolic localization (Fig. 2). For tagged Tb-AspRS2, on the other hand, a staining identical to the one seen with the mitochondrial marker was obtained. Furthermore, the two transgenic cell lines were subjected to a biochemical fractionation analysis, which showed that the tagged Tb-AspRS1 co-purifies with the cytosolic marker, whereas the tagged Tb-AspRS2 is recovered in the pellet together with the mitochondrial marker. Recently, the mitochondrial proteome of insect stage T. brucei has been comprehensively analyzed by mass spectroscopy. This analysis detected several AspRS2 peptides but none that corresponded to AspRS1 (29). In summary, these results show that the two trypanosomal AspRSs have a nonoverlapping intracellular distribution; Tb-AspRS1 is exclusively cytosolic, whereas Tb-AspRS2 is exclusively localized to the mitochondrion.

FIGURE 2.

Localization of trypanosomal AspRSs. A, top, double immunofluorescence analysis of a T. brucei cell line expressing Tb-AspRS1 carrying the Ty1 tag at its carboxyl terminus under the control of the tetracycline inducible (+Tet, −Tet) procyclin promoter. The cells were stained for DNA using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, for a subunit of the ATPase, serving as a mitochondrial marker and with a monoclonal antibody recognizing the Ty1 tag. Bottom, same as the top, but a cell line expressing carboxyl-terminally Ty1-tagged Tb-AspRS2 was analyzed. Bars, 10 μm. B, immunoblot analysis of total cellular (T), crude cytosolic (C), and crude mitochondrial extracts (M) for the presence of the Ty1-tagged Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2. Elongation factor 1a (EF-1a) served as a cytosolic marker, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KDH) served as a mitochondrial marker.

RNAi-mediated Ablation of Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2

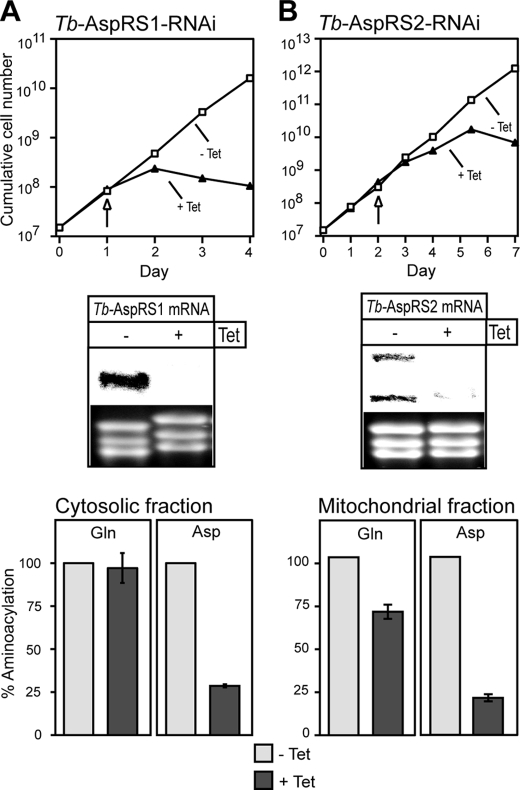

In order to determine the function of Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2, we established two stable transgenic cell lines that allow tetracycline-inducible RNAi-mediated ablation of each of the two enzymes independently. The Northern blots in the middle panels of Fig. 3, A and B, show that induction of RNAi in these two cell lines leads to specific degradation of the corresponding Tb-AspRS mRNAs. For the Tb-AspRS2 mRNA, we reproducibly detected two bands indicating that it might be alternatively polyadenylated, as has been observed for other trypanosomal mRNAs (30). Most importantly, following the depletion of the mRNAs, a growth arrest is observed 1–2 days (for Tb-AspRS1) and 3–4 days (for Tb-AspRS2) after the addition of tetracycline (Fig. 3, A and B, top). Thus, Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 are both essential for growth of insect stage T. brucei.

FIGURE 3.

Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 are essential and responsible for aspartyl-tRNAAsp formation in the cytosol and the mitochondria, respectively. A, top, growth curve in the presence and absence of tetracycline (+Tet, −Tet) of a representative clonal Tb-AspRS1 RNAi cell line. Middle, a Northern blot for Tb-AspRS1 mRNA. The time of sampling is indicated by the arrow. The rRNAs in the lower panel serve as loading controls. Bottom, in vitro aminoacylation reactions using RNA-free cytosolic fractions from uninduced (−Tet) and induced (+Tet) Tb-AspRS1 RNAi cells as a source of enzyme. Total tRNA of T. brucei and radioactive glutamine (left) or aspartate (right) were used as substrates. The background corresponding to the aminoacylation activity measured in the absence of added tRNAs (∼5% of the total activity) was determined for each reaction and subtracted. The net activity measured in uninduced cells was set to 100%. B, top and middle, growth curve of a representative clonal Tb-AspRS2 RNAi cell line and Northern blot (analogous to what is shown in A). Bottom, in vitro aminoacylation reactions using mitochondrial detergent extracts from uninduced (−Tet) and induced (+Tet) Tb-AspRS2 RNAi cells as a source of enzyme and total tRNA of T. brucei and radioactive glutamine (left) or aspartate (right) as substrates (analogous to what is shown in A).

In order to measure the biochemical phenotype of the Tb-AspRS1 RNAi cell line, we isolated RNA-free cytosolic fractions from uninduced and induced cells. The activities of AspRS and GlnRS (which serves as a control) in both cytosolic fractions were quantified by in vitro aminoacylation assays using labeled aspartate or glutamine and deacylated cytosolic tRNAs as substrates. Ablation of Tb-AspRS1 results in dramatic decrease of the cytosolic AspRS activity (Fig. 3A, bottom right) but does not affect GlnRS activity (Fig. 3A, bottom left).

To analyze the biochemical phenotype of the Tb-AspRS2 RNAi cell line, we isolated mitochondria from uninduced and induced cells. Detergent extracts of both mitochondrial fractions were then tested for in vitro AspRS and GlnRS activities using deacylated cytosolic tRNAs as substrate, as described above. Ablation of AspRS2 causes a dramatic decrease of mitochondrial AspRS activity (Fig. 3B, bottom right). Moreover, a 25% decrease of the mitochondrial GlnRS activity is also observed (Fig. 3B, bottom left). This decrease is most likely a pleiotropic effect caused by the growth arrest as observed before (12). These results show that, consistent with their intracellular localization, Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 are responsible for cytosolic and mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNAAsp formation, respectively.

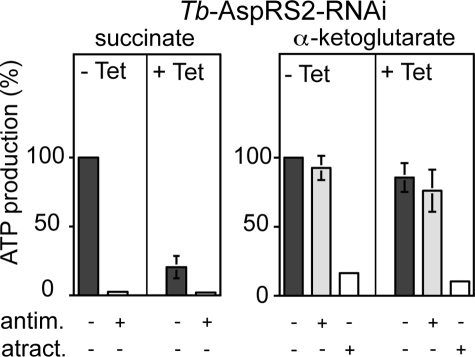

Effect of RNAi-mediated Ablation of Tb-AspRS2 on Mitochondrial ATP Production

Ablation of Tb-AspRS2 should selectively impair mitochondrial translation. However, mitochondrial translation in trypanosomatids is notoriously difficult to measure (31). Most of the proteins encoded in the mitochondrion of T. brucei function either directly in oxidative phosphorylation or as components of the mitochondrial translation machinery that produces them (32). Any interference with mitochondrial translation will ultimately also affect oxidative phosphorylation but not substrate level phosphorylation, for which all proteins are encoded in the nucleus. Thus, assessing the state of oxidative phosphorylation can be used as a proxy for the functionality of the mitochondrial translation system. The mitochondrion of procyclic T. brucei produces ATP by oxidative phosphorylation as well as by substrate level phosphorylation linked to the citric acid cycle (33, 34). Using isolated mitochondria, we have established an assay that allows quantitation of both modes of ATP production. In these assays, antimycin-sensitive oxidative phosphorylation is induced by the addition of succinate. Mitochondrial substrate level phosphorylation in the citric acid cycle, which is resistant to antimycin, is induced by the addition of α-ketoglutarate. Isolated mitochondria of T. brucei are depleted for nucleotides; therefore, ADP has to be added in all assays. Atractyloside treatment prevents mitochondrial import of the added ADP and therefore will abolish any type of mitochondrial ATP production (27, 33).

Fig. 4 shows that ablation of Tb-AspRS2 results in a loss of succinate-induced oxidative phosphorylation but does not affect mitochondrial substrate level phosphorylation assayed by α-ketoglutarate. These results are in line with the reduced mitochondrial AspRS activity observed in Tb-AspRS2-ablated cells and reinforce the essential function of Tb-AspRS2 in mitochondrial translation.

FIGURE 4.

Mitochondrial ATP production in the Tb-AspRS2 RNAi cell line. Uninduced cells (−Tet) are shown on the left, and induced cells (+Tet) are shown on the right of each panel. The substrate tested is indicated at the top, and the additions of antimycin (antim.) and atractyloside (atract.) are shown at the bottom of each panel. ATP production in mitochondria isolated from uninduced cells tested without antimycin or atractyloside is set to 100%. The bars represent means expressed as percentages from three independent inductions. S.E. values are indicated.

Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 Have Distinct Substrate Specificities

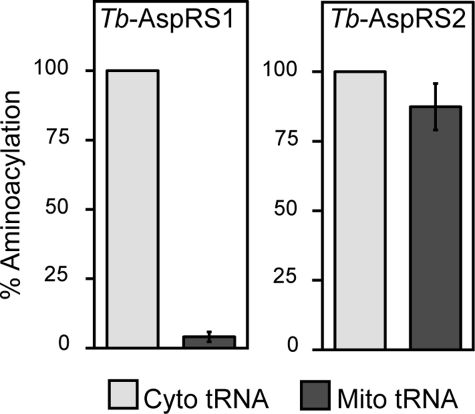

To address the question why T. brucei needs distinct cytosolic and mitochondrial AspRSs, we investigated the substrate specificities of the two enzymes. Recombinant Tb-AspRS1 was expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity. The activity of the recombinant enzyme was tested by in vitro aminoacylation assays using either cytosolic or mitochondrial tRNA fractions that contained identical amounts of tRNAAsp as substrate. The results in Fig. 5 show that recombinant Tb-AspRS1 efficiently aminoacylates the cytosolic tRNAAsp but cannot recognize the tRNAAsp present in the mitochondrial fraction.

FIGURE 5.

Tb-AspRS1 and Tb-AspRS2 have distinct substrate specificities. Left, in vitro aminoacylation using purified recombinant Tb-AspRS1 as a source of enzyme and isolated cytosolic or mitochondrial tRNAs, containing equal amounts of tRNAAsp, and radioactive aspartate as substrates. The background corresponding to the aminoacylation activity measured in the absence of added tRNAs (∼5% of the total activity) was determined for each reaction and subtracted. The net activity measured with cytosolic tRNA was set to 100%. Right, same as left, but mitochondrial detergent extract was used as a source of Tb-AspRS2 activity. 100% corresponds to 22–30 pmol or 5–7 pmol of added aspartate for AspRS1 and AspRS2, respectively.

It was not possible to perform the same analysis for Tb-AspRS2, since we were not able to produce recombinant enzyme in an active form. However, as shown before (Fig. 3B, bottom), Tb-AspRS2 activity can be measured in mitochondrial detergent extracts. Using these extracts, we could show that Tb-AspRS2, unlike Tb-AspRS1, is able to aminoacylate both the cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAsAsp with essentially the same efficiency. Hence, compared with Tb-AspRS1, Tb-AspRS2 has an expanded substrate specificity.

These experiments also show that cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAAsp must be physically different. We know that their sequence is identical, since they derive from the same nuclear gene; the difference must therefore be due to posttranscriptional nucleotide modifications. There are two principal possibilities; the postulated modification could either be mitochondria-specific, in which case it would act as an antideterminant for Tb-AspRS1, or it could be cytosol-specific, in which case it would be an identity determinant for Tb-AspRS1 that would not be required for Tb-AspRS2.

We believe the first scenario to be more likely for the following reasons. The identity elements on tRNAsAsp that are recognized by eukaryotic AspRSs consist of the anticodon and the discriminator nucleotide and do not require modified nucleotides (35). The same identity elements are probably also operational in T. brucei, since both the tRNAAsp and the Tb-AspRS1 are very similar to their counterparts in other eukaryotes. Moreover, we have analyzed the anticodon loop of the cytosolic tRNAAsp and did not find any evidence for nucleotide modification in that region (data not shown).

Thus, we predict that the inability of Tb-AspRS1 to aminoacylate mitochondrial tRNAAsp is due to a mitochondria-specific nucleotide modification that acts as an antideterminant for the cytosolic Tb-AspRS1. This is reminiscent of the trypanosomal Tb-TrpRS1, which cannot recognize imported tRNATrp due to RNA editing of the wobble nucleotide and thiolation of U33 (14). The location and nature of modified nucleotides in the mitochondrial tRNAAsp are currently unknown. However, the postulated modification in the imported tRNAAsp that prevents recognition by AspRS1 must be different from the ones found in the mitochondrial tRNATrp, since tRNAAsp is neither thiomodified nor subject to RNA editing (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The AspRS phylogeny (Fig. 1) reflects in large part the 16 S rRNA tree. Major features of the AspRS phylogeny have been documented previously, including instances of horizontal gene transfer (1) that do not obscure the evident pattern of vertical descent among the AspRSs with most species grouping in accord with accepted taxonomy. Plastid and mitochondrial AspRSs are clearly of bacterial origin. Asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase, a known late addition to protein synthesis that only partially displaced the earlier two-step route to Asn-tRNAAsn formation (36), evolved from a duplication of AspRS before the divergence of the archaeal and eukaryotic domains.

The tree shows that the eukaryotic AspRS evolutionary history was punctuated by several independent gene duplication events. A single duplication event among the mesophilic crenarchaea is also observed. As depicted in the phylogeny, early in the evolution of the trypanosomatid lineage, a duplication of the cytosolic (i.e. eukaryotic type) AspRS occurred. The duplicated gene was then retained in all extant trypanosomatids, resulting in the two eukaryotic type AspRS observed in T. brucei and other trypanosomatids.

A similar duplication pattern is also observed among several fungal lineages, from the taxonomic groups Basidiomycota and Pezizomycotina and also in Dictyostelium, Paramecium, Tetrahymena, and higher plants. Again here a less (shorter branch) and more divergent copy (longer branch) of AspRS is observed in each genome. The type 1 and 2 fungal AspRSs diverged early in the evolution of the fungal groups, before the divergence of the Basidiomycota and the Pezizomycotina clades. Two fungal species even encode a third yet more rapidly evolving AspRS that evolved from a more recent duplication of the type 1 fungal AspRS. Unlike the trypanosomatids and many of the deeply branching eukaryotes (see Fig. 1), these fungal groups, in addition to the two eukaryotic AspRSs, encode a mitochondrial AspRS, as does Dictyostelium, which are shown grouping on the bacterial side of the tree. Although in extant trypanosomes both AspRSs have clearly defined essential functions (one is responsible for cytosolic and the other for the mitochondrial AspRS activity), some eukaryotes and archaea have evolved as yet unknown uses for a second and even a third AspRS.

The endosymbiotic association between the progenitor of the eukaryotic lineage and a α-proteobacterium, endowed early eukaryotes (at least temporarily) with two complete sets of aaRSs. One set of aaRSs remained responsible for cytosolic translation, whereas the other set maintained the genetic code in the endosymbiont. During the evolutionary transition from endosymbiont to organelle, most of the genes from the original endosymbiont were lost or transferred to the nuclear genome. The mitochondrial aaRS genes were probably lost as some host aaRSs became dually targeted to the cytosol and the mitochondrion, thus eliminating the need to encode two sets of aaRSs.

In trypanosomatids, however, the loss of aaRS genes was extensive, and essentially all organellar aaRSs were replaced by dually targeted cytosolic aaRSs. This extensive loss can be explained by co-evolution of dual targeting of aaRSs with mitochondrial tRNA import. Many mitochondrial genomes have an incomplete set of tRNA genes and therefore import a fraction of cytosolic tRNAs. The trypanosomatid mitochondrion is unique in that it imports all of its tRNAs from the cytosol (11). A bioinformatic analysis suggests that the pattern of disappearance of distinct mitochondrial tRNA genes across eukaryotes might be due to the differential capabilities of mitochondrial aaRSs to charge imported eukaryotic type tRNAs (37). In line with this idea, mitochondrial import of cytosolic tRNAs may favor dual targeting of aaRSs or vice versa. Indeed, essentially all imported tRNAs in trypanosomatids and the single imported tRNALys in marsupials are aminoacylated by dually targeted aaRSs (14, 38). Moreover, all aaRSs of A. thaliana that are dually targeted to the mitochondria and the cytosol aminoacylate imported tRNAs (7). However, the fact that there are dually targeted aaRSs that aminoacylate mitochondrially encoded tRNAs, as well as imported tRNAs that are aminoacylated by organelle-specific aaRSs shows that there is no preset order of events.

However, there are two trypanosomal aaRSs, from which distinct cytosolic and mitochondrial forms are found, although their cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNA substrates derive from the same nuclear genes. These are the TrpRSs, which have been analyzed in detail, and the AspRSs, the subject of the present study. T. brucei also encodes two distinct LysRSs; however, their intracellular localization has not yet been experimentally analyzed, and they will therefore not be discussed here.

How do the two Tb-AspRSs and the two Tb-TrpRSs fit into this picture? All four enzymes are of the eukaryotic type, and the mitochondrial versions represent paralogues of the cytosolic enzymes. Thus, it is reasonable to consider the mitochondrial Tb-AspRS2 and Tb-TrpRS2 as relatively new additions to the set of trypanosomal aaRSs. This means that after an initial loss of all organelle-specific aaRSs, there was an expansion of the number of aaRSs by two novel, eukaryotic type enzymes that are exclusively mitochondrially localized.

For the trypanosomal TrpRSs, a plausible scenario is that nucleus-encoded unedited tRNATrp was imported into mitochondria and initially aminoacylated by a dually targeted Tb-TrpRS1-like enzyme. Then the mitochondrial stop codon UGA was reassigned to tryptophan, and the anticodon of the tRNATrp became edited to be able to recognize the UGA codon (15). The order of the two events is unknown; however, it is clear that RNA editing of the tRNATrp abolished charging by the Tb-TrpRS1-like enzyme, since it removed one of its essential identity determinants. Thus, decoding of the UGA required a modified version of the Tb-TrpRS1 that had an expanded substrate specificity (14). Gene duplication of Tb-TrpRS1 provided the raw material for the selection of such a protein, and one copy evolved to the Tb-TrpRS2 we observe today.

We envision a similar evolutionary scenario for the trypanosomal AspRSs in which the imported tRNAAsp was originally the substrate of a dually targeted Tb-AspRS1-like enzyme. Then the imported tRNAAsp was subjected to a nucleotide modification that interfered with the recognition by the Tb-AspRS1-like enzyme. Therefore, a novel mitochondrial AspRS was required that had an expanded substrate specificity that could accommodate the modified tRNA. This is supported by the fact that the branches leading to the type 2 trypanosomatid AspRSs are significantly longer than those tracing the evolution of the type 1 enzymes (Fig. 1). At the time of duplication, one copy was under an evolutionary constraint to continue functioning as a cytosolic AspRS. The evolutionary rate of the second copy was no longer constrained, and the gene must have been placed under selective pressure to take over the role of the mitochondrial AspRS. Thus, the increased evolutionary rate among the type 2 AspRSs is probably a signature of their adaptation from cytosolic to mitochondrial enzymes.

We do not know the nature of the mitochondria-specific nucleotide modification that affects recognition by Tb-AspRS1. However, since it is predicted to affect an identity element of Tb-AspRS1, it is most likely found in the anticodon loop. Mitochondria-specific modifications in imported tRNAs of trypanosomatids are widespread. Examples include the already discussed thiolation and anticodon editing of the tRNATrp (16), a bulky modification at the “universally unmodified” uridine at position 32 in the tRNATyr and modification of the penultimate cytidine before the anticodon in many if not all imported tRNAs (39). Mitochondrial translation in trypanosomatids is as in all mitochondria of the bacterial type. Thus, translation initiation and elongation factors, the rRNAs as well as ribosomal proteins, are of bacterial descent. The exception is the tRNAs, which, due to their import, are of eukaryotic type. Although in many cases, mitochondrial nucleotide modifications do not interfere with aminoacylation of the tRNA, certain modifications are critical for the formation of Trp-tRNATrp and Asp-tRNAAsp in trypanosomal mitochondria.

T. brucei is the causative agent of human sleeping sickness, a devastating disease that occurs in sub-Saharan Africa. Both prevention and treatment of sleeping sickness are still in a very unsatisfactory state (40). The significant evolutionary divergence between the human AspRS and TrpRS and the Tb-AspRS2 and Tb-TrpRS2, respectively, as well as the expanded substrate specificity of these enzymes make them attractive novel drug targets. It should be possible to exploit these differences for the development of drugs that selectively inhibit the mitochondrially localized enzymes of trypanosomes rather than the human ones in the cytosol. Moreover, Tb-AspRS2 and the Tb-TrpRS2 are sufficiently similar to their cytosolic orthologues that it is possible to model their structures by using the solved structures of yeast AspRS (41) and human TrpRS (42, 43) as templates. These structures could then provide a platform for rational drug design.

There is growing evidence that although oxidative phosphorylation does not occur in the bloodstream form of T. brucei, mitochondrial translation is nevertheless essential (44, 45). These results strongly suggest that the same is true for mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. However, drug target validation requires experimental evidence. Developing inhibitors of mitochondrial Tb-AspRS2 and Tb-TrpRS2 should await a determination of whether the two enzymes are essential for bloodstream forms of T. brucei cultured in vitro and in the animal model.

This work was supported by Swiss National Foundation Grant 3100A0_121937 (to A. S.) and by a grant from the VELUX Foundation (to F. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- aaRS

- aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- GlnRS

- glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase

- TrpRS

- tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase

- AspRS

- aspartyl-tRNA synthetase

- RNAi

- RNA interference.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woese C. R., Olsen G. J., Ibba M., Söll D. ( 2000) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 202– 236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donoghue P., Luthey-Schulten Z. ( 2003) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 550– 573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small I., Wintz H., Akashi K., Mireau H. ( 1998) Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 265– 277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatton B., Walter P., Ebel J. P., Lacroute F., Fasiolo F. ( 1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 52– 57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Natsoulis G., Hilger F., Fink G. R. ( 1986) Cell 46, 235– 243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinehart J., Krett B., Rubio M. A., Alfonzo J. D., Söll D. ( 2005) Genes Dev. 19, 583– 592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duchêne A. M., Giritch A., Hoffmann B., Cognat V., Lancelin D., Peeters N. M., Zaepfel M., Maréchal-Drouard L., Small I. D. ( 2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 16484– 16489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salinas T., Duchêne A. M., Maréchal-Drouard L. ( 2008) Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 320– 329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider A., Maréchal-Drouard L. ( 2000) Trends Cell Biol. 10, 509– 513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharyya S. N., Adhya S. ( 2004) RNA Biol. 1, 84– 88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider A. ( 2001) Int. J. Parasitol. 31, 1403– 1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rinehart J., Horn E. K., Wei D., Soll D., Schneider A. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1161– 1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berriman M., Ghedin E., Hertz-Fowler C., Blandin G., Renauld H., Bartholomeu D. C., Lennard N. J., Caler E., Hamlin N. E., Haas B., Böhme U., Hannick L., Aslett M. A., Shallom J., Marcello L., Hou L., Wickstead B., Alsmark U. C., Arrowsmith C., Atkin R. J., Barron A. J., Bringaud F., Brooks K., Carrington M., Cherevach I., Chillingworth T. J., Churcher C., Clark L. N., Corton C. H., Cronin A., Davies R. M., Doggett J., Djikeng A., Feldblyum T., Field M. C., Fraser A., Goodhead I., Hance Z., Harper D., Harris B. R., Hauser H., Hostetler J., Ivens A., Jagels K., Johnson D., Johnson J., Jones K., Kerhornou A. X., Koo H., Larke N., Landfear S., Leech C. L., Line A., Lord A., Macleod A., Mooney P. J., Moule S., Martin D. M., Morgan G. W., Mungall K., Norbertczak H., Ormond D., Pai G., Peacock C. S., Peterson J., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Rajandream M. A., Reitter C., Salzberg S. L., Sanders M., Schobel S., Sharp S., Simmonds M., Simpson A. J., Tallon L., Turner C. M., Tait A., Tivey A. R., Van Aken S., Walker D., Wanless D., Wang S., White B., White O., Whitehead S., Woodward J., Wortman J., Adams M. D., Embley T. M., Gull K., Ullu E., Barry J. D., Fairlamb A. H., Opperdoes F., Barrell B. G., Donelson J. E., Hall N., Fraser C. M., Melville S. E., El-Sayed N. M. ( 2005) Science 309, 416– 42216020726 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charrière F., Helgadóttir S., Horn E. K., Söll D., Schneider A. ( 2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 6847– 6852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfonzo J. D., Blanc V., Estévez A. M., Rubio M. A., Simpson L. ( 1999) EMBO J. 18, 7056– 7062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crain P. F., Alfonzo J. D., Rozenski J., Kapushoc S. T., McCloskey J. A., Simpson L. ( 2002) RNA 8, 752– 761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markowitz V. M., Szeto E., Palaniappan K., Grechkin Y., Chu K., Chen I. M., Dubchak I., Anderson I., Lykidis A., Mavromatis K., Ivanova N. N., Kyrpides N. C. ( 2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D528– D533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutta S., Burkhardt K., Swaminathan G. J., Kosada T., Henrick K., Nakamura H., Berman H. M. ( 2008) Methods Mol. Biol. 426, 81– 101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts E., Eargle J., Wright D., Luthey-Schulten Z. ( 2006) BMC Bioinformatics 7, 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donoghue P., Sethi A., Woese C. R., Luthey-Schulten Z. A. ( 2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 19003– 19008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edgar R. C. ( 2004) BMC Bioinformatics 5, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guindon S., Gascuel O. ( 2003) Syst. Biol. 52, 696– 704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wirtz E., Leal S., Ochatt C., Cross G. A. ( 1999) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99, 89– 101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastin P., Bagherzadeh Z., Matthews K. R., Gull K. ( 1996) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 77, 235– 239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCulloch R., Vassella E., Burton P., Boshart M., Barry J. D. ( 2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 262, 53– 86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider A., Charrière F., Pusnik M., Horn E. K. ( 2007) Methods Mol. Biol. 372, 67– 80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider A., Bouzaidi-Tiali N., Chanez A. L., Bulliard L. ( 2007) Methods Mol. Biol. 372, 379– 387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Giezen M., Tovar J., Clark C. G. ( 2005) Int. Rev. Cytol. 244, 175– 225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panigrahi A. K., Ogata Y., Zíková A., Anupama A., Dalley R. A., Acestor N., Myler P. J., Stuart K. D. ( 2009) Proteomics 9, 434– 450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vassella E., Braun R., Roditi I. ( 1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 1359– 1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horváth A., Nebohácova M., Lukes J., Maslov D. A. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7222– 7230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feagin J. E. ( 2000) Int. J. Parasitol. 30, 371– 390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bochud-Allemann N., Schneider A. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32849– 32854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Besteiro S., Barrett M. P., Rivière L., Bringaud F. ( 2005) Trends Parasitol. 21, 185– 191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giegé R., Sissler M., Florentz C. ( 1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 5017– 5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheppard K., Söll D. ( 2008) J. Mol. Biol. 377, 831– 844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider A. ( 2001) Trends Genet. 17, 557– 559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dörner M., Altmann M., Pääbo S., Mörl M. ( 2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2688– 2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider A., McNally K. P., Agabian N. ( 1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 3699– 3705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lüscher A., de Koning H. P., Mäser P. ( 2007) Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 555– 567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sauter C., Lorber B., Cavarelli J., Moras D., Giegé R. ( 2000) J. Mol. Biol. 299, 1313– 1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang X. L., Otero F. J., Skene R. J., McRee D. E., Schimmel P., Ribas de Pouplana L. ( 2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 15376– 15380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen N., Guo L., Yang B., Jin Y., Ding J. ( 2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 3246– 3258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnaufer A., Clark-Walker G. D., Steinberg A. G., Stuart K. ( 2005) EMBO J. 24, 4029– 4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnaufer A., Panigrahi A. K., Panicucci B., Igo R. P., Jr., Wirtz E., Salavati R., Stuart K. ( 2001) Science 291, 2159– 2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]