Abstract

Biosynthesis of surfactant protein C (SP-C) by alveolar type 2 cells requires proteolytic processing of a 21-kDa propeptide (proSP-C21) in post-Golgi compartments to yield a 3.7-kDa mature form. Scanning alanine mutagenesis, binding assays, and co-immunoprecipitation were used to characterize the proSP-C targeting domain. Delivery of proSP-C21 to distal processing organelles is dependent upon the NH2-terminal cytoplasmic SP-C propeptide, which contains a conserved PPDY motif. In A549 cells, transfection of EGFP/proSP-C21 constructs containing polyalanine substitution for Glu11–Thr18, 13PPDY16, or 14P,16Y produced endoplasmic reticulum retention of the fusion proteins. Protein-protein interactions of proSP-C with known WW domains were screened using a solid-phase array that revealed binding of the proSP-C NH2 terminus to several WW domains found in the Nedd4 family of E3 ligases. Specificity of the interaction was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation of proSP-C and Nedd4 or Nedd4-2 in epithelial cell lines. By Western blotting and reverse transcription-PCR, both forms were detected in primary human type 2 cells. Knockdown of Nedd4-2 by small interference RNA transfection of cultured human type 2 cells blocked processing of 35S-labeled proSP-C21. Mutagenesis of potential acceptor sites for ubiquitination in the cytosolic domain of proSP-C (Lys6, Lys34, or both) failed to inhibit trafficking of EGFP/proSP-C21. These results indicate that PPDY-mediated interaction with Nedd4 E3-ligases is required for trafficking of proSP-C. We speculate that the Nedd4/proSP-C tandem is part of a larger protein complex containing a ubiquitinated component that further directs its transport.

Surfactant protein C (SP-C)3 is a hydrophobic lung-specific protein that co-isolates with the biophysically active phospholipid fraction of pulmonary surfactant (1). The 3.7-kDa alveolar form of SP-C (SP-C3.7 or mature SP-C) is a 35-amino acid, valine-rich peptide that results from synthesis of a 197 amino acid precursor form (proSP-C21). Within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), proSP-C21 exists as a type II bitopic transmembrane protein (Ncyt/Clumen), which remains integrally membrane-associated while it is extensively processed by four post-translational endoproteolytic cleavages that take place in post-Golgi compartments (2–6). The resulting mature protein is transferred into the lumen of lamellar bodies for secretion into the alveolar space together with surfactant phospholipid and SP-B (7). Thus, the complete biosynthesis of SP-C3.7 is critically dependent upon oligomeric sorting and targeting of proSP-C21 to subcellular processing compartments distal to the ER/Golgi.

Using deletional mutagenesis, we had previously shown that the NH2-terminal propeptide flanking domain (NTP) of proSP-C, which is oriented into the cytosol, contained potential targeting motifs for post-Golgi trafficking (8, 9). The candidate region included the amino acid sequence Met10–Thr18 and, when present, was sufficient to direct transfected EGFP-proSP-C protein chimeras to post-ER, acidic vesicular compartments within A549 lung epithelial cells. Comparative analyses reveal that the primary sequence (MESPPDY) and its position within the proSP-C NTP is 100% conserved across all species (10–13). Subsequent to this initial report, proline-rich sequences (XPPXY) in other proteins were identified as important motifs facilitating trans-interactions with tryptophan-containing (WW domain) protein ligands (14, 15).

WW domains, named for structurally homologous, highly compact (35–45 amino acids) modular domains containing a pair of conserved tryptophan residues spaced 20–22 amino acids apart, adopt an antiparallel three stranded fold capable of interacting in trans with proline-rich recognition complexes (16). Based on their ligand predilection, WW domains fall into two major and two minor groups (15). Major Group I members bind polypeptides with the minimal core consensus sequence X-Pro-Pro-X-Tyr (XPPXY motif). Contained within Group I are a family of E3 ubiquitin ligases that include Nedd4, Nedd4-2 (= Nedd4-like or Nedd4-L), WWP1, and YAP. These members are highly evolutionarily conserved and can interact with a variety of cellular proteins, including the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), β2-adrenergic receptor, lysosome-associated transmembrane protein 5, and Commisureless (in Drosophila) suggesting a pivotal role in many diverse cellular signaling processes primarily through regulation of trafficking. For the majority of cases, the domain ligands are directly monoubiquitinated and targeted to either endosomal or degradative (lysosomal or proteasomal) compartments (17–21). Alterations in XPPXY motif-WW domain interactions have been shown to play a role in the molecular pathogenesis of human disease. For example, inherited forms of hypertension (Liddle syndrome) in which mutations in the PY (XPPXY) motif of the β-ENaC subunit produce alterations in ENaC trafficking from the cell surface (22). The role of Nedd4 or other Group I family members in mediating anterograde trafficking of secreted proteins is largely undefined.

On the basis of our previous data and many recent proteomic studies characterizing the potential role of proline-rich motifs in protein trafficking, we hypothesized that anterograde trafficking of proSP-C21 from proximal (ER-Golgi) compartments is dependent upon the interaction of its cytosolic PY (PPDY) motif with WW domain containing proteins. In the current report, utilizing scanning alanine mutagenesis, solid phase array binding, and co-immunoprecipitation, we demonstrate that proSP-C21 interacts with two members of the Group I WW domain family, Nedd4 and Nedd4-2, via its cytosolic PY motif. Both isoforms were found to be expressed in primary human alveolar type 2 cells. In gene silencing experiments using primary human type 2 cells in culture, Nedd4-2 exerted the dominant effect on proSP-C biosynthesis. Interestingly, although Nedd4 or Nedd4-2 binding is a necessary and sufficient requirement for trafficking, this translocation does not require direct proSP-C ubiquitination. Collectively these data offer the first detailed characterization of the role of E3 family ubiquitin ligases, typically reserved for the retrograde trafficking of proteins in the endosomal and degradative pathways, as a post-translational targeting paradigm for anterograde transport of a protein that is synthesized, processed, and released by the regulated secretory pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The pEGFP-C1 plasmid was purchased from Clontech. Tissue culture medium was produced by the Cell Center Facility, University of Pennsylvania. Trans-35S-label was purchased from ICN/Flow, Inc. (Irvine, CA). Precast gels and buffers for SDS-PAGE (Novex®) were obtained from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA). Except where noted, all other reagents were electrophoresis, tissue culture, or analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma or Bio-Rad.

Monospecific polyclonal antisera (NPROSP-C11–23 and NPROSP-C2–9) directed against distinct, non-overlapping regions of the NH2 propeptide flanking domain of rat proSP-C were previously produced in rabbits using synthetic peptide immunogens (6, 8). Anti-NPROSP-C11–23 (epitope = Glu11–Gln23) recognizes proSP-C21 and all major processing intermediates but does not recognize mature SP-C. Anti-NPROSP-C2–9 (epitope = Asp2–Leu9) also recognizes proSP-C21 and does not recognize mature SP-C.

Monoclonal anti-HA (clone 12CA5 recognizing a peptide epitope from the hemagglutinin protein of human influenza virus) was obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Polyclonal anti-calnexin NT antiserum was purchased from Stressgen, Inc. (Victoria, BC, Canada). A monoclonal anti-CD-63 antibody was obtained from Immunotech, Inc. (Marseilles Cedex, France). Monoclonal antisera against green fluorescent protein (GFP) was purchased form Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against the WW2 domain of rat Nedd4 was obtained from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). This antibody cross-reacts against the human Nedd4 isoform and also recognizes Nedd4-2 isoforms. Monoclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody was purchased from Chemicon, Inc. (Temecula, CA). Monoclonal anti-β-actin (clone AC-15) was obtained from Sigma. A monoclonal mouse anti-GST antibody (clone GST3-4C, Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) was used to detect GST fusion proteins. Texas Red-conjugated monoclonal and polyclonal secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Bio-Rad. EGFP/Nedd4 (ΔC2 clone) and EGFP/Nedd4-2 plasmids, previously characterized (17, 23), were the generous gift of Dr. Peter Snyder at the University of Iowa.

SP-C cDNA Expression Constructs

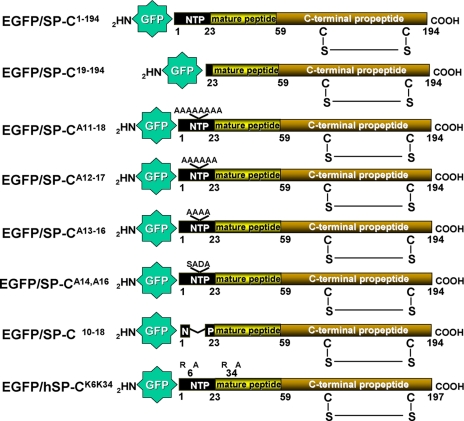

cDNA constructs synthesized, cloned, and utilized in this study are schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Where indicated, additional constructs produced previously were also utilized (8, 9, 24). All procedures involving oligonucleotide and cDNA manipulations were performed as previously described (8, 9, 24–27).

FIGURE 1.

EGFP/SP-C Constructs. Inserts containing wild-type, mutant rat SP-C, or mutant human SP-C were generated by PCR and subcloned into the EGFPC1 vector as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Amino acid nomenclature is based on published SP-C sequences (10). Top to bottom: EGFP/SP-C1–194 containing wild-type rat SP-C shown with putative intra-chain disulfide bonding between Cys186 and Cys122. “NTP” = N-terminal propeptide; EGFP/SP-C19–194 is a deletional construct produced by removal of amino acids 1–18 of the NTP; EGFP/SP-CA11–18, EGFP/SP-CA12–17, EGFP/SP-CA13–16, and EGFP/SP-CA14A16 each contain polyalanine (A) substitution at the indicated residues in the NH2-flanking propeptide; EGFP/SP-CΔ10–18 contains a deletion of the conserved sequence Met10–Thr18 in the cytoplasmic NTP; EGFP/hSP-CK6K34 represents full-length human SP-C for, which either arginine (R) or alanine (A) is substituted at lysine (K) residues 6 and/or 34.

pcDNA3-SP-C1–194

The vector for the expression of untagged wild-type proSP-C in eukaryotic cells was produced by subcloning of a full-length rat SP-C1–194 cDNA (816 bp) (10) insert into the pcDNA3 expression vector at the EcoRI site of the polylinker as described before (24).

HA-tagged proSP-C1–194

The hemagglutinin (HA) tag (YPYDVPDYA) was added to the NH2 terminus of rat SP-C1–194 by PCR using pcDNA-SP-C1–194 as a template, as previously described (25, 26). The 5′ (forward) primer was an 82-mer and contained a KpnI site (bold), a Kozak sequence, and the HA coding sequence (underlined): TAC AAG GGT ACC ATG GAC TAC CCA TAC GAT GTT CCA GAT TAC GCT GCT GAC ATG GGT AGC AAA GAG GTA CTG ATG GAG AGC. The 3′ (reverse) primer was a 21-mer that contained an XhoI site (bold): TCT AGA TGC ATG CTC GAG CG.

EGFP/proSP-C Fusion Proteins

A chimera consisting of EGFP fused to the NH2 terminus of wild-type rat SP-C (EGFP/SP-C1–194) was cloned into the EGFPC1 expression vector and has been previously characterized (9). Using this as template, EGFP-mutant SP-C chimeras containing an NH2-terminal truncation (SP-C19–194) or internal deletion (SP-CΔ10–18) were subsequently produced and characterized (8).

Scanning polyalanine mutagenesis of the NH2-terminal propeptide (SP-CA11–18, SP-CA12–17, SP-CA13–16, and SP-CA16A16) shown in Fig. 1 was performed using a three-step PCR amplification and subcloning strategy with oligonucleotide sets listed in supplemental Table S1. Oligonucleotides corresponding to rat SPC codons 1–18 (both + and − strands) or 1–17 (both + and − strands) were synthesized commercially (Sigma-Genosys) A Primary Annealing Reaction was performed with 10 μm of each complementary oligonucleotide strand by boiling and subsequent slow cooling in polystyrene insulation to permit complementary annealing yielding double-stranded mutant pieces. The second step involved Primary PCR (see supplemental Table S1) to yield products containing codons 18–194 or 19–194, respectively. A Secondary PCR to join the annealed oligonucleotide and Primary PCR products was performed by complementary and overlapping pairing of the extreme 3′ and 5′ ends, respectively, to yield a full-length cDNA containing the poly Ala mutations. Unique restriction sites were engineered at both the 5′ and 3′ ends to facilitate unidirectional cloning into EGFPC1 using BspEI and XhoI.

Site-directed mutagenesis to substitute alanine or arginine for one or both lysine residues contained within the NH2-terminal cytosolic domain of proSP-C21 (Lys6 and Lys34) was performed using a single two primer single PCR as previously described (27). The oligonucleotide primers are listed in supplemental Table S2, and the previously characterized pcDNAhSP-C(6+) expression vector (28) served as the template. Purified products were subcloned back into EGFPC1 using BglII and BamHI.

For all constructs generated, fidelity of the PCR reactions and cloning were demonstrated by automated DNA sequencing of the coding regions performed in both directions by the Core Facility in the Department of Genetics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Cell Models and Transfection

Cell Lines

The lung epithelial cell line A549 was originally obtained through the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and has been used in prior studies (9, 24, 27). Human embryonic kidney epithelial cells (HEK293) were also obtained through the ATCC and maintained in culture in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal calf serum. A549 or HEK293 cells grown to 50% confluence were transiently transfected with EGFP/SP-C constructs (10 μg/dish) or co-transfected with HA/SP-C1–194 and EGFP/Nedd4 constructs (5 μg/construct/dish) by CaPO4 precipitation or LipofectamineTM (Invitrogen) as previously described (9).

Mouse Type 2 Cells

Primary mouse type 2 pneumocytes, isolated from C57BL/6 mouse lungs using dispase, mesh filtration, and panning over IgG-coated and uncoated plates as described previously (29, 30), were kindly provided by Dr. Sandra Bates and the Cell Culture Core at the Institute for Environmental Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Cell pellets were prepared for Western blotting from freshly isolated cells by detergent lysis as previously published (2, 8).

Isolation, Culture, and siRNA Transfection of Primary Human Type 2 Cells

Enriched populations of epithelial cells were prepared from second-trimester human fetal lung from the Birth Defects Laboratory in the Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington Medical Center (Seattle, WA) or from Advanced Biosciences Resources, Inc. (Alameda, CA). All tissue was obtained and handled in compliance with state and federal law, and under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Fetal lung epithelial cells were prepared and cultured on tissue culture plastic in Weymouth medium in the presence or absence of 10 nm dexamethasone, 0.1 mm 8-Br-cAMP, and 0.1 mm isobutyl methylxanthine (DCI) to induce and maintain type 2 cell differentiation as described (31).

Transfection of naïve lung epithelial cells with siRNA after isolation was done using the Amaxa Mammalian Epithelial Cell Nucleofector solution and Amaxa program M05 as previously described (32). siRNA (10–20 pmol) was added to 100 μl of Nucleofector solution prior to executing the transfection protocol. Cells were then plated into 2 ml of Weymouth media with 10% fetal calf serum. After culture overnight to allow recovery and attachment, medium was changed to Weymouth with DCI for 4 days without serum to induce differentiation of type 2 cells. Gene silencing of Nedd4 isoforms was achieved using combinations of commercially available siRNA (Silencer®, Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) for Nedd4 (siRNA no. 120777) and Nedd4-2 (siRNA no. 23570) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation of GST-SP-C Fusion Proteins for Screening Assays

For evaluation of protein-protein interactions, an inducible GST gene fusion system in Escherichia coli was used to express and create ligand domain specific protein fusions. The NH2 propeptide domain of wild-type (Asp2–Gln23) and polyalanine-mutagenized, PPDY-deficient (SP-CA11–18) proSP-C depicted in Fig. 1 were amplified by PCR (supplemental Table S3) and subcloned into the GST vector, pGEX-2TK (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) using the EcoR1 and BamH1 restriction enzyme sites in the vector. Transformed BL21 E. coli were grown to log phase and treated with isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (100 μm) × 4 h. Bacteria pelleted by centrifugation were resuspended, lysed by probe sonication, and cleared by centrifugation.

Solid Phase WW Protein Array Assay

To screen domain-ligand interactions, solubilized E. coli lysate containing either GST-SP-C2–23 (wild type) or GST-SP-CA11–18 were diluted to ∼1 mg/ml total protein and applied directly to TranssignalTM WW Domain Array I membranes (Panomics, Inc., Freemont, CA) per manufacturer's instructions. After washing, binding signals were detected by secondary probing with anti-NPROSP-C2–9 followed by goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase and development with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Amersham Biosciences).

Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence images were viewed on an Olympus I-70 inverted fluorescence microscope using a High Q FITC filter package for EGFP (excitation, 480 nm; emission, 535/550 nm; Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT). Where indicated, Texas Red-tagged immunostaining of permeabilized EGFP/SP-C-transfected cells, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, was performed and visualized with a High Q TR filter (excitation, 560/555 nm; emission, 645/675 nm) as described (8, 27). Image acquisition, processing, and overlay analysis were performed using Metamorph IMAGE1 (Molecular Devices, Inc., Downingtown, PA).

SDS-PAGE

Cell pellets collected by scraping and centrifugation at 300 × g were solubilized with 40 μl of solubilization buffer (50 mm Tris, 190 mm NaCl, 6 mm EDTA, 2% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.4). Following centrifugation at 8000 × g for 30 s to remove nuclei, proteins were separated by electrophoresis on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose (33).

Immunoprecipitation

Lysates prepared from either 35S-labeled human type 2 cells or transfected epithelial cell lines were immunoprecipitated using specific anti-GFP, -Nedd4, -NPROP-C, or -HA antiserum as previously published (8). Proteins were captured using either Protein A-agarose beads (Sigma) or MAGmol magnetic Protein A Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., Auburn, CA), separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose as described below. Membranes containing transferred protein were either probed for co-precipitating partners by Western blotting or subjected to autoradiography.

Western Blotting

Immunoblotting of transferred samples was done using successive incubations with primary immune sera and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies as previously described (25). The resulting fluorescence images visualized by ECL were captured either by exposure to film or by direct acquisition using the Kodak 2000 Image System. Specific band intensities were quantitated using Kodak1D software (Version 3.0).

Statistical Analysis

Parametric data were expressed as mean ± S.E., and experimental groups were compared utilizing unpaired two-tailed Student's t test or analysis of variance using Instat version 3.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Mutation of the NH2-flanking Propeptide to Remove a PPDY Motif Blocks Transport and Processing of proSP-C

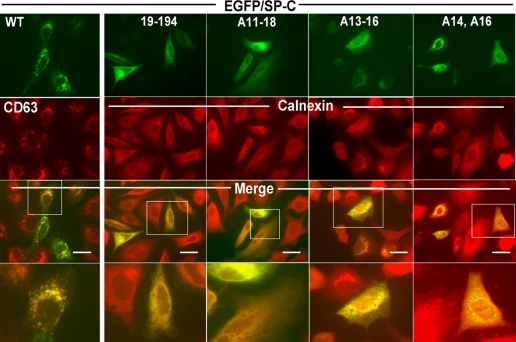

To characterize the role of NH2-flanking propeptide in SP-C trafficking, EGFP fusion proteins containing polyalanine substitutions of the proSP-C NH2 terminus were evaluated after transfection into A549 cells. Within 48 h of introduction of plasmid cDNA, expression of the EGFP/SP-C1–194 fusion protein was detected in cytoplasmic vesicles (Fig. 2), which co-localizes with CD63, a marker of lysosomal-like organelles (24, 25). By both deletion analysis (SP-C19–194) and polyalanine substitution (SP-CA11–18), EGFP/proSP-C fusion proteins each lacking the PDDY domain were expressed in a diffuse reticular pattern that co-localizes with calnexin consistent with ER retention (24, 25). The role of the PPDY domain in trafficking was then directly assessed by polyalanine substitution of only these four residues, which also resulted in disruption of normal trafficking of the EGFP fusion protein (Fig. 2). To exclude the possibility that these findings were the result of gross protein misfolding, missense mutation of only Pro14 and Tyr16 within the PPDY domain also produced similar ER retention (Fig. 2). Single substitutions of alanine for either Ser12 or Ser17 did not alter EGFP/proSP-C trafficking to cytosolic vesicles indicating that PPDY alone was required for targeting (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

The PPDY domain within Met10–Thr18 is critical for targeting of proSP-C. The subcellular distribution of wild-type and mutant EGFP/SP-C constructs transiently transfected into A549 cells was determined by fluorescence microscopy. Plasmid DNA encoding EGFP/SP-C1–194 (= WT), the NH2-terminal truncation mutant EGFP/SP-C19–194, polyalanine mutants EGFP/SP-CA11–18, EGFP/SP-CA13–16, or EGFP/SP-CA14A16 were introduced into A549 cells grown on coverslips (70% confluent) using LipofectamineTM as described under “Experimental Procedures.” 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed and stained for the lysosomal-like organelle marker CD63 or the ER marker calnexin using polyclonal antibodies and a Texas Red goat anti-rabbit secondary antiserum. Double label fluorescence images for EGFP (top panels) or Texas Red expression (second row) were acquired, and single images were digitally overlaid using Metamorph imaging software (version 7.5, Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). As shown in the merged images (third row), EGFP/SP-C1–194 (= WT) was found to co-localize with CD63 in cytosolic vesicles, whereas EGFP/SP-C19–194, EGFP/SP-CA11–18, EGFP/SP-CA13–16, and EGFP/SP-CA14A16 were each expressed in a diffuse cytosolic reticular pattern that co-localized with calnexin. Bar = 10 μm. Regions delineated by the solid boxes were enlarged to provide additional resolution (bottom row).

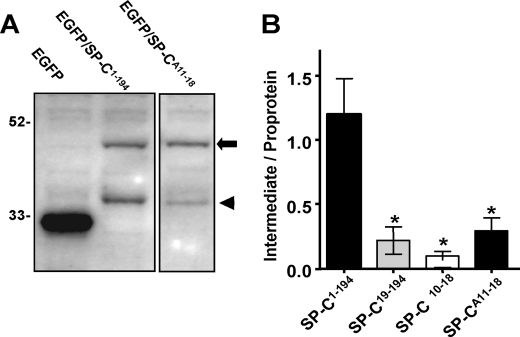

The successful export of proSP-C21 to CD63-positive cytoplasmic vesicles in A549 cells results in its partial proteolytic processing from removal of the COOH propeptide, which can be used as a quantitative surrogate of anterograde trafficking (24, 25). In Fig. 3, A549 cells transiently transfected with EGFP/SP-C isoforms were evaluated for processing by Western blotting. The successful transport of the wild-type EGFP/SP-C1–194 fusion protein from the ER was associated with appearance of a lower molecular weight intermediate due to removal of the COOH propeptide consistent with previously published data (25). In contrast, the polyalanine EGFP/SP-CA11–18 fusion protein that was retained in the ER underwent minimal processing. The relative degree of processing of wild-type proSP-C21 was compared with that of EGFP/SP-CA11–18 and 2 NH2-terminal deletion mutants by densitometric scanning of Western blots. In Fig. 3B, quantitative data from multiple independent experiments shows a markedly decreased ratio of intermediate/primary translation product consistent with inhibition of processing. The degree of processing of proSP-C NH2 mutants was only 10–15% that of the wild-type isoform. Collectively these data demonstrate that the NH2-terminal flanking domain of proSP-C contains a functional targeting motif required for its direction from proximal compartments.

FIGURE 3.

Processing of EGFP/SP-C mutants. A549 cells were transiently transfected with EGFP-C1, EGFP/SP-C1–194, EGFP/SP-C19–194, EGFP/SP-CΔ11–18, or EGFP/SP-CA11–18 using CaPO4. Nuclear-free lysates were prepared from cell pellets as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, 50% of each lysate was subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-GFP, and bands were visualized using ECL. EGFP-C1 was expressed as a major product with Mr 27,000. EGFP/SP-C1–194 was expressed as a primary translation product with Mr of 48,000 with a lower molecular weight band (Mr = 38,000–40,000) consistent with COOH propeptide processing. EGFP/SP-CA11–18 was expressed predominantly as a primary product of Mr 48,000 with minimal processing intermediate. B, for each condition, densitometry was performed on the primary translation product and processing intermediates, and the ratio of the processed intermediate/proprotein was calculated (n = 3 separate experiments; mean ± S.E.). At steady state, ∼50% of EGFP/SP-C1–194 is in the form of processed intermediates, whereas all NH2-terminal mutants were only ∼10–15% processed (*, p < 0.05 versus EGFP/SP-C1–194 by analysis of variance).

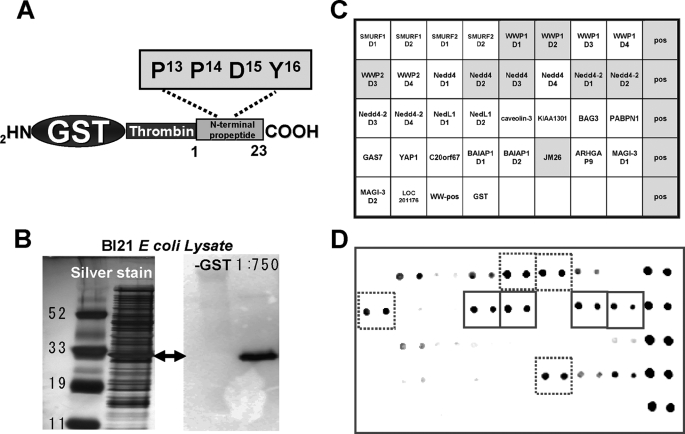

The proSP-C NH2 Terminus Is a Ligand for WW Domains

To test the hypothesis that the PPDY motif of proSP-C could interact with WW domain ligands, we created GST fusion proteins containing only the NH2-terminal propeptide (NTP) of proSP-C (Fig. 4A). Lysates of E. coli expressing the GST-NTPSP-C fusion (Fig. 4B) were used as probes in a membrane array to screen for WW domain binding. Fig. 4 (C and D) shows a representative array binding experiment and corresponding grid map. Using an antibody against the proSP-C NH2 terminus, specific and selective binding signals were visualized with ECL. In three separate experiments, we observed the strongest and most consistent binding of GST-NTPSP-C to WW domains located in Nedd4, Nedd4-2, and WWP1 (Nedd-4-like ubiquitin ligase, accession number NP_008944). Using an identical BL21 lysate containing a mutagenized GST-NTPSP- C1–23A11–18 (i.e. PPDY-deficient), no binding to any of the Nedd4/Nedd4-2 WW domains was observed (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 4.

A GST fusion protein containing the SP-C NTP is a ligand for WW domains. A, schematic diagram of the coding insert for expression of a GST-tagged NTP of proSP-C containing the PPDY motif amplified and subcloned into PGEX-2TK as described under “Experimental Procedures” and supplemental Table S1. B, expression of GST-SP-CNTP in BL21 bacterial cells upon induction with isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Lysate was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (left) or immunoblotting with α-GST (right). C, schematic diagram of WW Domain Array I (Panomics, Inc.) showing the positions of immobilized WW domain motifs (two spots per motif) used to screen for SP-CNTP/WW domain binding. Pos = positive control. D, dot immunoblot generated by incubation of WHOLE BL21 lysate containing GST/SP-CNTP with the WW Domain I membrane per the manufacturer's guidelines, and binding signals were visualized by secondary incubation with anti-NPROSP-C2–9 and ECL. Representative film shows selective binding to several WW domains contained in Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 E3 ligases (solid boxes) as well as other related proteins (dashed boxes).

Nedd4 Isoforms Interact with proSP-C in an PPXY-dependent Manner

Because Smurf E3 ligases have been shown to be important mainly for Smad targeting (34) and WWP1 is not expressed in distal airway epithelia (35) we hypothesized that Nedd4 and/or Nedd4-2 were essential for proSP-C21 transport from proximal compartments in lung epithelial cells. To address this, a series of studies was performed to characterize specific interactions of Nedd4 homologues with proSP-C.

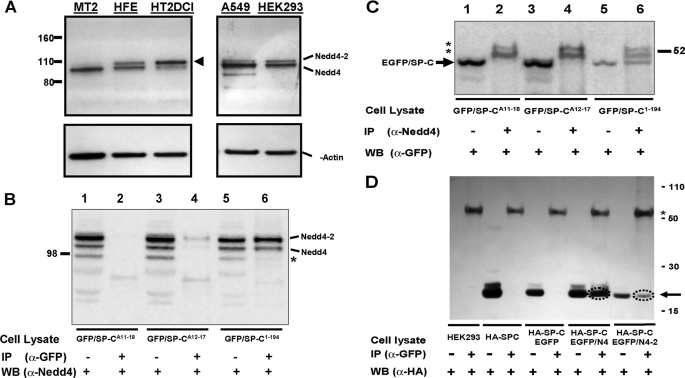

First, the spatial expression of Nedd4 isoforms was determined. Using primary isolates of human fetal lung epithelial cells and cultured human type 2 cells as well as two human epithelial cell lines previously utilized for the study of SP-C trafficking (A549 and HEK293), Western blotting with a polyclonal pan-Nedd4 antibody demonstrated that significant levels of Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 were each expressed in all three human lung cell lines as well as HEK293 cells (Fig. 5A). The expression of both isoforms was confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Using isoform-specific primers for Nedd4 and Nedd4-2, mRNA for both homologues was detected (supplemental Table S3).

FIGURE 5.

Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 are expressed in epithelial cells and interact with proSP-C. A, cell lysates from freshly isolated mouse alveolar type 2 cells (MT2), freshly isolated epithelial cells from second trimester human fetal lung (HFE), human alveolar type 2 cells induced by culture in DCI (HT2DCI), A549 cells and HEK293 cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with a panNedd4 antibody. Position of Novex Sharp Standards is shown at left. To control for loading, blots were re-probed for β-actin (lower panel). Human epithelial cell lines express both Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 homologues as indicated. Note the dramatic increase in Nedd4-2 expression in human lung epithelial cells cultured for 96 h in DCI to promote type 2 cell differentiation (arrowhead). B and C, endogenous Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 specifically interact with the NTP of EGFP/proSP-C. A549 cells were transiently transfected with either EGFP/SP-C1–194, or one of two NTP polyalanine mutants EGFP/SP-CA11–18 or EGFP/SP-CA12–17 using CaPO4 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, 72 h after transfection, A549 cell lysates expressing EGFP-tagged SP-C isoforms were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal α-GFP and immunoblotted with polyclonal α-Nedd4 (lanes 2, 4, and 6). To control for input, lanes 1, 3, and 5 represent 5% of the indicated total cell lysate that was directly immunoblotted with α-Nedd4. EGFP/SP-C1–194 captures two bands corresponding to Nedd-4 and Nedd4-2, which were not recognized by either EGFP/SP-CA11–18 or EGFP/SP-CA12–17. An additional band (*) present in A549 cell lysates was detected by the panNedd4 antibody by immunoblotting but not by immunoprecipitation. C, the identical lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal α-Nedd4 and immunoblotted with monoclonal α-GFP (lanes 2, 4, and 6). To control for input, lanes 1, 3, and 5 represent 5% of the indicated total cell lysate that was directly immunoblotted with α-GFP. Nedd4 isoforms interacted only with EGFP/SP-C1–194 (arrow). **, nonspecific doublet corresponding to IgG in the immunoprecipitated samples. D, exogenous Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 each interact with the NTP of wild-type EGFP/proSP-C. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with either HA-SP-C1–194 alone or in combination with the EGFP/Nedd4 (ΔC2 clone) or EGFP/Nedd4-2 plasmid. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal α-GFP, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with monoclonal α-HA. To control for input, 5% of the indicated total cell lysate was also directly immunoblotted with α-HA (the position of HA-SP_C is indicated by the arrow). Both EGFP/Nedd4 and EGFP/Nedd4-2 but not EGFP captured HA-SP-C1–194 (circle). “HEK293” = non-transfected controls. *, nonspecific band corresponding to IgG.

Next, the interaction of Nedd4 isoforms with the proSP-C NTP was further defined using co-immunoprecipitation studies. Transient transfection of two different NTP mutants EGFP/SP-CA12–17 or EGFP/SP-CA11–18 as well as EGFP/SP-C1–194 into A549 cells was performed, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP followed by Western blotting with a polyclonal pan-Nedd4 antiserum (Fig. 5B). By co-immunoprecipitation, EGFP/SP-C1–194 was capable of capturing both Nedd4 isoforms endogenously expressed by these cells. However, neither polyalanine mutant lacking the PPDY domain (EGFP/SP-CA12–17 nor EGFP/SP-CA11–18) was capable of interacting with Nedd4 isoforms. In Fig. 5C, the complimentary experiment was performed. By immunoblotting alone, lysates from transfected cells contained detectable levels EGFP/SP-C fusion proteins (wild-type or polyalanine mutants). Using anti-Nedd4, immunoprecipitation then captured a single band corresponding to wild-type EGFP/SP-C.

Finally, expression constructs containing EGFP-tagged Nedd4 isoforms (EGFP/Nedd4 (ΔC2 clone) and EGFP/Nedd4-2) were utilized to directly assess whether individual Nedd4 isoforms interacted with wild-type SP-C. When transfected into epithelial cells, EGFP/Nedd4 and EGFP/Nedd4-2 proteins were each detectable by Western blotting and expressed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm (supplemental Fig. S2). Following double transfection of HEK293 cells with HA-SP-C1–194 and either EGFP/Nedd4 or EGFP/Nedd4-2, immunoprecipitation of either lysate with anti-GFP captured HA-SP-C1–194 as demonstrated by the HA-reactive band with Mr 22,000 (Fig. 5D).

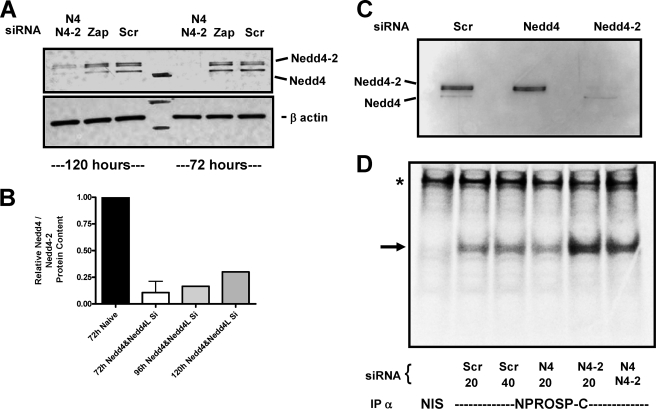

Nedd4-2 but Not Nedd4 Is Required for Trafficking and Processing of SP-C

To assess the role of Nedd4 interactions with proSP-C on SP-C biosynthesis, knockdown studies were performed in cultured primary human alveolar type 2 cells (Fig. 6). The time course Nedd4 protein knockdown was addressed by Western blotting following treatment with siRNA initially directed against both Nedd4 isoforms. In Fig. 6A, compared with a scrambled siRNA reagent, greater than 90% knockdown of both Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 proteins was achieved. Quantitative analysis of bands indicated that knockdown was maintained from 72 up to 120 h (Fig. 6B). Using individual Nedd4 siRNA treatments, selective knockdown of either Nedd4 or Nedd4-2 could also be achieved (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Knockdown of Nedd4 homologues inhibits SP-C processing in human type 2 cells. Freshly isolated epithelial cells from second trimester human fetal lung were electroporated with 20 nm Nedd4 siRNA (#120777), Nedd4-2 (#23570), a combination of both Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 (40 nm total), 20 nm to40 nm scrambled control siRNA, or buffer alone and then cultured in DCI for 72–120 h. A, representative Western blot analyses of cell lysates from siRNA treated, scrambled (Scr), and control (Zap) cells immunoblotted with polyclonal α-Nedd4 showing inhibition of expression of both Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 (upper doublet) homologues at 72 and 120 h. B, the time course of the knockdown of Nedd4/Nedd4-2 protein expression was determined by densitometry of immunopositive bands from Western blots. Data were normalized to 72 h untreated cells and expressed as range of mean ± range (n = 2 experiments). C, Western blot analyses with polyclonal α-Nedd4 of lysates from cells subjected to individual Nedd4 siRNA treatments showing specific inhibition of either Nedd4 or Nedd4-2 (doublet) at 120 h. D, cells in culture treated with siRNA for 120 h were continuously labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 2 h and immunoprecipitated with either non-immune serum (NIS) or NPROSP-C11–23 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Phosphorimaging acquired autoradiograph (representative of three separate experiments) showing accumulation of proSP-C primary translation product in cells treated with Nedd4-2 siRNA. The arrow depicts the position of proSP-C21 primary translation product; *, nonspecific band shown as a loading control.

To accurately assess the effect of Nedd4 silencing on SP-C transport, we used proSP-C21 as a surrogate marker of Nedd4-dependent transport. Importantly, the use of Nedd4/Nedd-2 siRNA did not affect the expression of SP-C mRNA as assessed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (supplemental Table S4). Fig. 6D shows that type 2 cells subjected to combined knockdown of Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 for 120 h accumulated greater amounts of proSP-C21 than cells pretreated with scrambled siRNA. Following immunoprecipitation with antiNPROSP-C11–23, SDS-PAGE, and autoradiography, lysates from cells continuously labeled with [35S]cysteine/methionine for 2 h had increased steady-state levels of 35S-proSP-C21 indicating impairment of transport from the ER. When cells were pretreated with siRNA to achieve selective knockdown of either Nedd4 or Nedd-2, only cells lacking Nedd4-2 demonstrated an increase in 35S-proSP-C21 indicating that SP-C transport was predominantly dependent upon Nedd4-2.

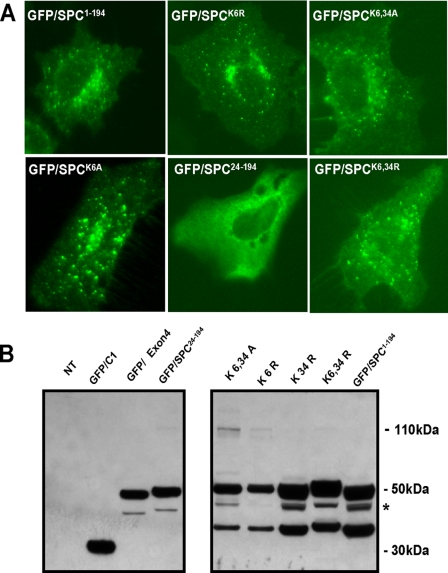

Nedd4-dependent Trafficking of proSP-C Does Not Require Ubiquitination

Because the interaction of Nedd4-2 with proSP-C is required for its processing, we next tested if direct ubiquitination of proSP-C21 was also necessary for trafficking. Mutant forms of proSP-C lacking each or both of two cytoplasmic lysine residues located in the NTP were generated to render proSP-C ubiquitination impaired (Fig. 1). To analyze the requirement for these motifs in SP-C transport, we tested the ability of the transfected ubiquitination mutants to translocate to cytosolic vesicles and be proteolytically processed. Transient transfection of GFP-tagged lysine mutants into epithelial cells produced expression in cytoplasmic vesicles (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, Western blotting for assessment of processing confirmed that single and double lysine-deficient proSP-C fusion proteins were capable of undergoing post-translational processing (Fig. 7B). In addition, using co-transfection of HA-tagged proSP-C1–194 and His-tagged ubiquitin, we were unable to detect specific mono- or di-ubiquitination of proSP-C (data not shown). Taken together these results suggest that interactions with Nedd4-2 rather than its direct ubiquitination serves as a transport signal for proSP-C to cytosolic processing compartments.

FIGURE 7.

Ubiquitination of proSP-C is not required for Nedd4- mediated trafficking. HEK293 cells transiently transfected with either EGFP/hSP-C1–197, or missense mutants containing substitution of cytosolic lysine (K) or arginine (R) at positions 6 and 34 of proSP-C as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Positive controls for ER retention or aggregation, EGFP/SP-C24–194or EGFP/hSP-CΔExon4 were also utilized. A, nuclear-free lysates prepared from cell pellets were immunoblotted with polyclonal α-GFP, and bands were visualized using ECL. EGFP-C1 was expressed as a major product with Mr 27,000. EGFP/SP-C1–194 was expressed as a primary translation product with Mr of 48,000 with a lower molecular weight band (Mr = 33,000) consistent with COOH propeptide processing. All K and R mutants were expressed and exhibited the same relative degree of COOH-terminal processing. In contrast, EGFP/SP-C24–194 and EGFP/hSP-CΔExon4 were expressed predominantly as primary products of Mr 48,000 and 45,000, respectively, with minimal processing. *, nonspecific cleavage product representing cleavage of a portion of EGFP. B, images for EGFP expression were acquired 72 h after transfection by fluorescence microscopy. In contrast to the ER retention mutants, EGFP/SP-C1–194 as well as all ubiquitin-deficient mutants were transported to cytosolic vesicles.

DISCUSSION

Due to its extreme hydrophobicity and avidity for lipid membranes, SP-C represents a structurally and functionally challenging protein that must be synthesized and trafficked through the regulated secretory pathway of the type 2 cell. In this study, we defined the targeting motif and structural requirements for the successful transport and initiation of post-translational processing of proSP-C. We had previously shown using epitope-specific antisera, immunogold electron microscopy, metabolic labeling, and chimeric fusion proteins that proteolytic processing of proSP-C21 is critically dependent upon its successful export from ER/Golgi compartments and that this event requires the presence of an intact NH2-terminal propeptide (2, 4, 8, 9, 25). The current data extends these findings by demonstrating that a specific amino acid sequence, PPDY, contained within the NH2-flanking propeptide (NTP) is required for proper anterograde transport of proSP-C from the ER to cytosolic, organellar processing compartments. This “PY” motif was found to specifically interact with two members of an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase family, Nedd4 and Nedd4-2, with Nedd4-2 exerting the dominant effect on SP-C transport in primary human type 2 cells.

Previous studies demonstrating a potential role for the NH2 terminus for targeting of proSP-C relied upon truncation or deletional mutagenesis (8, 9, 25, 36). In this study, scanning alanine mutagenesis was utilized to further narrow the targeting motif to the conserved cytosolic PDDY motif. Importantly, conservative alanine substitution of only two residues (Pro14 and Tyr16) within the PPDY motif was also sufficient to disrupt trafficking indicating that ER retention of all the constructs was due to the loss of a specific targeting motif and unlikely due to gross protein misfolding (Fig. 2). In addition, the alterations in SP-C trafficking are unlikely to be due to the EGFP tag. Previously, we have shown that both untagged proSP-C as well as an EGFP-tagged SP-C fusion proteins are successfully targeted to CD63 (+) cytosolic vesicles, whereas mutant SP-C isoforms are mistrafficked independent of the tags (HA, EGFP, or dsRed) utilized (25, 27, 52).

The observed alteration in subcellular expression patterns produced by SP-C NH2 mutants was also reflected by changes in their post-translational processing (Fig. 3). Densitometric evaluation of precursors and products by Western blotting was done to quantify degrees of processing. At steady state, 48 h after transfection, A549 cells expressed wild-type SP-C in two isoforms, a proprotein precursor and partially processed intermediate product that exist in approximately a 45:55 ratio. Although small amounts of the intermediate could still be detected after expression of the Ala11–18 mutant, when normalized to wild-type values, disruption of the NTP targeting domain results in over 85% inhibition in processing. We have observed similar values in previous published studies that examined the role of homomeric association on SP-C biosynthesis (25).

The PPDY motif initially identified within the rat proSP-C NTP is conserved across all known species (10, 12, 37–39). Protein data base queries (ELM Motif Search) had suggested the possibility that proSP-C could interact with WW domains via this motif. Using the SP-C NTP fused to GST as a ligand, screening for potential protein-protein interactions by solid phase protein arrays identified several possible WW domain-containing proteins, including several members of an E3 ubiquitin ligase family (Fig. 4). From this list, candidate proteins were further evaluated using Western blotting of lung epithelial cells and co-immunoprecipitation, and Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 were identified as proSP-C interacting proteins in alveolar type 2 cells.

Redundancy of Nedd4/Nedd4-2 binding is not a totally unexpected characteristic of HECT E3 ligase family members. Although Nedd4-2 is now felt to be critical to ENaC regulation (23, 40, 41), early studies had first implicated Nedd4 as a binding partner and regulator of cell surface ENaC density through modulation of its internalization to endosomes (17, 20). On a biochemical basis, the overlap in enzymatic function and substrate specificities for Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 also contributes to this redundancy of function (42). Despite this, it was eventually through the development of selective silencing strategies that a dominant effect of Nedd4-2 on ENaC trafficking could be ascertained (23). Based on this, we adopted a similar selective silencing strategy to demonstrate that, functionally, Nedd4-2 was shown to provide the dominant effect in the targeting of proSP-C to distal processing compartments in cultured human type 2 cells in vitro (Fig. 6). A potential confounder in this culture system is the presence of glucocorticoid and cAMP to facilitate in vitro differentiation. Indeed, Western blotting demonstrates a significant selective up-regulation of Nedd4-2 protein after culture in DCI when compared with freshly isolated naive lung epithelial cells (Fig. 5A). We have also noted previously a selective induction of Nedd4-2 in this in vitro system at the mRNA level using microarray analysis where a 3-fold increase in Nedd4-2 after 72 h occurred with culture in DCI (31). Nedd4 mRNA was unchanged under similar conditions. Thus, the dominant effect seen with the use of Nedd4-2 siRNA may have been due, in part, to the relevant abundance of Nedd4-2 versus Nedd4 in this culture system. Given the overlap observed with co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6D), preferential expression of one homologue could preclude our ability to detect any effect from single knockdown of the less prevalent homologue. Therefore, with the available in vitro models, we cannot exclude functional redundancy for Nedd4 homologues in SP-C biosynthesis.

Both Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 have been the subject of gene-targeting strategies in mice in vivo (43, 44). Transgenic mice homozygous for disruption of the NEDD4 gene are neonatal lethal (43). Although the lungs of the knockout mice are small, the phenotype of this model is dominated by defects in insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling (also Nedd4-dependent), which would preclude detection of ENaC trafficking/functional defects, alterations in SP-C biosynthesis, or disruption of any other PY-dependent phenotype in type 2 cells. NEDD4L null (i.e. Nedd4-2-deficient) mice are born and develop normally but have Na+-sensitive systemic hypertension due to abnormal ENaC trafficking in the kidney. A complete pulmonary phenotype of this model has not been described. Any mistrafficking of proSP-C due to Nedd4-2 deficiency resulting in selective SP-C deficiency may not be phenotypically dominant as the SP-C null mouse survives to adulthood (45, 46) due to redundancy in the biophysical activity provided by surfactant protein B. However, a preliminary report of a second independent Nedd4-2-deficient mouse indicated that perinatal lethality secondary to respiratory insufficiency can occur (47). Additional studies will be required to completely characterize the relative role of each Nedd-4 homologue in SP-C biosynthesis in vivo.

Mechanistically, the effects of Nedd4 ligases on intracellular protein trafficking are often mediated by trans-ubiquitination of the binding partner. Monoubiquitination of proteins has been well documented as a sorting signal within cells (48). Traditionally, the role of ubiquitin sorting signal has been shown to be both important for endocytosis of plasma membrane proteins. Down-regulation of the β-adrenergic receptor and ENaC as well as internalization of the EGFR have been shown to be mediated via trans-ubiquitination by E3 ligase family members (23, 40, 49–51). Although ubiquitination via E3 ligase has also been shown to facilitate trans-Golgi network sorting and transport of proteins to multivesicular bodies for degradation in yeast, the role of either Nedd4 or ubiquitination in sorting of a secreted protein within the classic regulated pathway of mammalian cells is less clear. Interestingly, we and others have shown that proSP-C is routed directly to multivesicular bodies and subsequently to the lamellar body, a lysosomal-like organelle in type 2 cells, prior to regulated secretion. Thus, the data presented here suggest a new role for Nedd4 homologues in anterograde protein trafficking.

Using inhibition of proSP-C processing as a quantitative surrogate for transport from ER/Golgi compartments, knockdown of Nedd4 isoforms has demonstrated their importance in proSP-C biosynthetic routing. Interestingly, in contrast to protein trafficked via the endosomal pathway, direct monoubiquitination of the cargo protein, proSP-C was not observed. This is not likely due to insensitivity of the standard methodology utilized. In previous studies we have shown that mutation in the COOH terminus of proSP-C, associated with human interstitial lung disease, result in aggregation and polyubiquitination of proSP-C, which can readily be detected in cells transfected with EGFP-tagged mutant forms (26, 27). To further confirm that ubiquitination of proSP-C was not required for its biosynthesis, we mutated the cytosolic domain of proSP-C to remove candidate monoubiquitination sites at lysine residues located at positions 6 and 34. When transfected, these lysine mutants were trafficked normally, appearing in lysosome-like organelles (Fig. 7). Our results do not exclude the possibility that Nedd4 might ubiquitinate SP-C at other molecular sites that could impact trafficking. Alternatively, the interaction of Nedd4/Nedd4-2 and proSP-C could also result in ubiquitination of another yet to be identified protein as part of a larger transport complex. A similar model has been shown for trafficking of the multispanning lysosomal-associated protein transmembrane 5 (LAPTM5). Similar to SP-C, Nedd4 is required for transport of LAPTM5 directly to lysosomes but neither Nedd4 nor LAPTM5 are directly ubiquitinated (19).

The present studies have expanded our understanding of SP-C trafficking and processing and have important relevance for the pathogenesis of interstitial lung disease. Previously, we and others have shown that mutations in the proSP-C primary sequence are associated with the development of interstitial lung disease in both pediatric and adult patients. To date, the known mutations fall into one of three categories (1). The first and largest category involves mutations in a region of the proSP-C termed BRICHOS which is associated with gross protein misfolding, aggregation, induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, and promotion of apoptosis and generation of proinflammatory cytokines (52). The second category of proSP-C mutations are also associated with the development of interstitial lung disease but are characterized by accumulation of mutant protein in endosomes and lysosomes (53, 54). The third set of mutations in the proSP-C NTP results in retention in the ER (55). It is possible, on the basis of these studies, that mutations in proSP-C NTP could alter its interactions with Nedd4-2/Nedd4 leading to ER retention resulting in lung disease from impaired trafficking. This paradigm has been previously described for the pathogenesis of Liddle syndrome in which altered amounts of ENaC expression on epithelial cell surfaces result from mutations in ENaC that disrupt its interaction with Nedd4-2. Conversely, alterations in the function or binding of proSP-C to Nedd4/Nedd4-2 through alterations in Nedd4 function itself might be expected to be associated with the pathogenesis of some forms of parenchymal lung disease.

In summary, our results indicate that proSP-C contains at least five of the “bells and whistles” that contribute to its complete biosynthesis. The mature SP-C domain (residues 24–59) functions as a non-cleavable signal peptide that is required both for its translocation to the ER membrane and its proper oligomeric self-association prior to trafficking (8, 25). In addition, juxtamembrane charged residues encoded by its primary sequence provide cues for its proper topographical orientation in the ER membrane (56). The current data extend these findings with novel results demonstrating that anterograde transport of SP-C can be mediated by a PPDY domain that modulates an interaction with Nedd4 E3 ligases, a first for a secreted protein. However, given the lack of direct monoubiquitination there are likely other factors acting in “trans” that further facilitate SP-C trafficking. Finally, while folding of SP-C has also been shown to be important in both normal anterograde trafficking and in disease, it now appears that alterations in the primary sequence of the NH2 propeptide terminus that may affect its interactions with Nedd4 should also be considered as a potentially significant contributing factor to the growing number of interstitial lung diseases associated with protein misfolding or mistrafficking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Peter Snyder at the University of Iowa for provision of the EGFP-tagged Nedd4 expression constructs and to Zhenguo Zhang and Dr. Linda Gonzalez at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia for assistance with isolation and electroporation of human type 2 cells.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-19737 (to M. F. B.), HL-059959 (to S. G.), and HL090732 (to S. M.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2 and Tables S1–S4.

- SP-C

- pulmonary surfactant protein C (3.7 kDa)

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- Nedd

- neuronal precursor-cell expressed developmentally down-regulated

- YAP

- yes-associated protein

- ENaC

- epithelial Na+ channel

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- HA

- hemagglutinin antigen

- E3

- ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- siRNA

- small interference RNA

- NTP

- NH2-terminal propeptide flanking domain

- LAPTM5

- lysosomal-associated protein transmembrane 5.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beers M. F., Mulugeta S. ( 2005) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 663– 696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beers M. F., Lomax C. ( 1995) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 269, L744– 753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasch F., ten Brinke A., Johnen G., Ochs M., Kapp N., Müller K. M., Beers M. F., Fehrenbach H., Richter J., Batenburg J. J., Bühling F. ( 2002) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 26, 659– 670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beers M. F. ( 1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14361– 14370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vorbroker D. K., Voorhout W. F., Weaver T. E., Whitsett J. A. ( 1995) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 269, L727– 733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beers M. F., Kim C. Y., Dodia C., Fisher A. B. ( 1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20318– 20328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voorhout W. F., Weaver T. E., Haagsman H. P., Geuze H. J., Van Golde L. M. ( 1993) Microsc. Res. Tech. 26, 366– 373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson A. L., Braidotti P., Pietra G. G., Russo S. J., Kabore A., Wang W. J., Beers M. F. ( 2001) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24, 253– 263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russo S. J., Wang W. J., Lomax C., Beers M. F. ( 1999) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 277, L1034– 1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher J. H., Shannon J. M., Hofmann T., Mason R. J. ( 1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 995, 225– 230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akinbi H. T., Breslin J. S., Ikegami M., Iwamoto H. S., Clark J. C., Whitsett J. A., Jobe A. H., Weaver T. E. ( 1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9640– 9647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glasser S. W., Korfhagen T. R., Perme C. M., Pilot-Matias T. J., Kister S. E., Whitsett J. A. ( 1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 10326– 10331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warr R. G., Hawgood S., Buckley D. I., Crisp T. M., Schilling J., Benson B. J., Ballard P. L., Clements J. A., White R. T. ( 1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84, 7915– 7919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay B. K., Williamson M. P., Sudol M. ( 2000) Faseb J 14, 231– 241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudol M., Hunter T. ( 2000) Cell 103, 1001– 1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X., Poy F., Zhang R., Joachimiak A., Sudol M., Eck M. J. ( 2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 634– 638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snyder P. M., Olson D. R., McDonald F. J., Bucher D. B. ( 2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28321– 28326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ing B., Shteiman-Kotler A., Castelli M., Henry P., Pak Y., Stewart B., Boulianne G. L., Rotin D. ( 2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 481– 496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pak Y., Glowacka W. K., Bruce M. C., Pham N., Rotin D. ( 2006) J. Cell Biol. 175, 631– 645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry P. C., Kanelis V., O'Brien M. C., Kim B., Gautschi I., Forman-Kay J., Schild L., Rotin D. ( 2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20019– 20028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myat A., Henry P., McCabe V., Flintoft L., Rotin D., Tear G. ( 2002) Neuron 35, 447– 459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staub O., Dho S., Henry P., Correa J., Ishikawa T., McGlade J., Rotin D. ( 1996) EMBO J. 15, 2371– 2380 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder P. M., Steines J. C., Olson D. R. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5042– 5046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beers M. F., Lomax C. A., Russo S. J. ( 1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15287– 15293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W. J., Russo S. J., Mulugeta S., Beers M. F. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19929– 19937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W. J., Mulugeta S., Russo S. J., Beers M. F. ( 2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 683– 692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabore A. F., Wang W. J., Russo S. J., Beers M. F. ( 2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 293– 302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solarin K. O., Ballard P. L., Guttentag S. H., Lomax C. A., Beers M. F. ( 1997) Pediatr. Res. 42, 356– 364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guttentag S. H., Akhtar A., Tao J. Q., Atochina E., Rusiniak M. E., Swank R. T., Bates S. R. ( 2005) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 33, 14– 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bortnick A. E., Favari E., Tao J. Q., Francone O. L., Reilly M., Zhang Y., Rothblat G. H., Bates S. R. ( 2003) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 285, L869– L878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzales L. W., Guttentag S. H., Wade K. C., Postle A. D., Ballard P. L. ( 2002) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 283, L940– L951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerson K. D., Foster C. D., Zhang P., Zhang Z., Rosenblatt M. M., Guttentag S. H. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10330– 10338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli U. K. ( 1970) Nature 227, 680– 685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi W., Chen H., Sun J., Chen C., Zhao J., Wang Y. L., Anderson K. D., Warburton D. ( 2004) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 286, L293– L300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malbert-Colas L., Fay M., Cluzeaud F., Blot-Chabaud M., Farman N., Dhermy D., Lecomte M. C. ( 2003) Pflugers Arch. 447, 35– 43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conkright J. J., Bridges J. P., Na C. L., Voorhout W. F., Trapnell B., Glasser S. W., Weaver T. E. ( 2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14658– 14664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasser S. W., Korfhagen T. R., Bruno M. D., Dey C., Whitsett J. A. ( 1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 21986– 21991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glasser S. W., Korfhagen T. R., Weaver T. E., Clark J. C., Pilot-Matias T., Meuth J., Fox J. L., Whitsett J. A. ( 1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 9– 12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore K. J., D'Amore-Bruno M. A., Korfhagen T. R., Glasser S. W., Whitsett J. A., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G. ( 1992) Genomics 12, 388– 393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabra R., Knight K. K., Zhou R., Snyder P. M. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6033– 6039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou R., Patel S. V., Snyder P. M. ( 2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20207– 20212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fotia A. B., Cook D. I., Kumar S. ( 2006) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 38, 472– 479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao X. R., Lill N. L., Boase N., Shi P. P., Croucher D. R., Shan H., Qu J., Sweezer E. M., Place T., Kirby P. A., Daly R. J., Kumar S., Yang B. ( 2008) Sci. STKE 1, ra5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi P. P., Cao X. R., Sweezer E. M., Kinney T. S., Williams N. R., Husted R. F., Nair R., Weiss R. M., Williamson R. A., Sigmund C. D., Snyder P. M., Staub O., Stokes J. B., Yang B. ( 2008) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295, F462– 470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glasser S. W., Burhans M. S., Korfhagen T. R., Na C. L., Sly P. D., Ross G. F., Ikegami W., Whitsett J. A. ( 2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 6366– 6371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glasser S. W., Detmer E. A., Ikegami M., Na C. L., Stahlman M. T., Whitsett J. A. ( 2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14291– 14298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar S., Boase N., Yang B., Daly R., Townley S., Dinudom A., Cook D. I., Poronnik P., Rychkov G. Y.Proc. Australian Physiol. Soc. 39, 11P. 11-30-2008 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staub O., Rotin D. ( 2006) Physiol. Rev. 86, 669– 707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shenoy S. K., Xiao K., Venkataramanan V., Snyder P. M., Freedman N. J., Weissman A. M. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22166– 22176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snyder P. M., Olson D. R., Thomas B. C. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5– 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li T., Koshy S., Folkesson H. G. ( 2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 293, L1069– 1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulugeta S., Nguyen V., Russo S. J., Muniswamy M., Beers M. F. ( 2005) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32, 521– 530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brasch F., Griese M., Tredano M., Johnen G., Ochs M., Rieger C., Mulugeta S., Müller K. M., Bahuau M., Beers M. F. ( 2004) Eur. Respir. J. 24, 30– 39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevens P. A., Pettenazzo A., Brasch F., Mulugeta S., Baritussio A., Ochs M., Morrison L., Russo S. J., Beers M. F. ( 2005) Pediatr. Res. 57, 89– 98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nogee L. M., Dunbar A. E., 3rd, Wert S., Askin F., Hamvas A., Whitsett J. A. ( 2002) Chest 121, 20S– 21S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mulugeta S., Beers M. F. ( 2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47979– 47986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.