Abstract

A functional collaboration between growth factor receptors such as platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and integrins is required for effective signal transduction in response to soluble growth factors. However, the mechanisms of synergistic PDGFR/integrin signaling remain poorly understood. Our previous work showed that cell surface tissue transglutaminase (tTG) induces clustering of integrins and amplifies integrin signaling by acting as an integrin binding adhesion co-receptor for fibronectin. Here we report that in fibroblasts tTG enhances PDGFR-integrin association by interacting with PDGFR and bridging the two receptors on the cell surface. The interaction between tTG and PDGFR reduces cellular levels of the receptor by accelerating its turnover. Moreover, the association of PDGFR with tTG causes receptor clustering, increases PDGF binding, promotes adhesion-mediated and growth factor-induced PDGFR activation, and up-regulates downstream signaling. Importantly, tTG is required for efficient PDGF-dependent proliferation and migration of fibroblasts. These results reveal a previously unrecognized role for cell surface tTG in the regulation of the joint PDGFR/integrin signaling and PDGFR-dependent cell responses.

Adhesion of cells to the extracellular matrix (ECM)2 regulates a wide range of cellular processes, including cell survival, growth, migration, and differentiation. A central paradigm in the field entails both physical association and functional collaboration between integrins and growth factor receptors (GFRs) in the regulation of cell responses to the ECM and soluble growth factors (1). In particular, the engagement of β1 and αvβ3 integrins with ECM ligands transiently activates platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor-tyrosine kinase even in the absence of its soluble ligands and promotes and sustains growth factor-initiated signaling by PDGFR (2). Despite a significance of this synergistic signaling, the molecular mechanisms underlying the cross-talk between the two receptor systems remain unknown. A direct or indirect association between these two types of signaling receptors may be enhanced by their co-sequestering in cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains (3). Because integrins and receptor-tyrosine kinases share many downstream signaling targets, integrin-ECM interaction may also increase availability of signal relay enzymes and adapter proteins to receptor-tyrosine kinases by promoting their recruitment from cytosol to the plasma membrane (4).

PDGF is a major survival factor, mitogen, and motogen for mesenchymal cells (5). This ligand-receptor pair is implicated in tumor-associated processes, including autocrine growth stimulation of tumor cells, tumor angiogenesis, and regulation of stromal fibroblasts (6). Atherosclerosis in the vessel wall and restenosis after angioplasty also involve hyperactivation of the PDGF-PDGFR signaling axis in vascular smooth muscle cells (7). Likewise, skin wound healing and liver, lung, and kidney fibrosis depend on PDGF-mediated signaling and cell responses (8). Importantly, ECM composition and cell-matrix interactions modulate cell responsiveness to PDGF (9).

Upon binding a dimeric PDGF molecule, PDGFR undergoes dimerization and autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues in trans because of the juxtaposition of cytoplasmic tails of the receptor. Phosphorylation of the conserved tyrosine residue in the kinase domain (Tyr-849 of PDGFRα and Tyr-857 of PDGFRβ) increases catalytic activity of the kinases, whereas autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues outside the kinase domain creates docking sites for signal transduction proteins containing Src homology 2 domains. The latter include various enzymes such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cγ, the Src family tyrosine kinases, the tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2, and the GTPase activating protein for Ras, RasGAP. Other PDGFR binding partners including Grb2, Grb7, Nck, Shc, and Crk lacking enzymatic activity but serve adapter functions in the downstream signaling pathways (10).

Previous studies revealed a transient PDGF-independent tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGFRβ in human fibroblasts during adhesion on fibronectin or collagen type I, whereas similar PDGFRβ activation response was reproduced by application of external strain to quiescent cells (2). Clustering of integrins with fibronectin-coated beads was shown to stimulate PDGFR phosphorylation in fibroblasts (11). Furthermore, fibronectin was found to promote PDGF-mediated signaling in fibroblasts by increasing association of phosphatase Shp-2 with PDGFR and limiting the time that the negative signaling regulator, RasGAP, interacts with the receptor (4). Whereas these results implicate cell-ECM interactions and integrin function in the regulation of PDGFR activity, many details of this functional cross-talk remain unknown.

Tissue transglutaminase (tTG) is a multifunctional protein that possesses Ca2+-dependent transamidating and GTPase activities (12). On the surface of various cells, all the tTG forms stable non-covalent complexes with β1 and β3 integrins and functionally collaborates with these receptors by acting as a co-receptor for fibronectin (13). This adhesive function of tTG is involved in the assembly of fibronectin matrices and cell migration on fibronectin (14–16). tTG broadly affects integrin signaling by promoting their clustering and increasing activation of focal adhesion kinase and RhoA (13, 17). Thus, we set to examine whether signaling mediated by GFRs, which depends on the integrin function, is altered by tTG.

Here we present a novel mechanistic insight into the cross-talk between integrin and PDGFR signaling pathways. We provide evidence that tTG interacts with PDGFR on the cell surface and mediates its physical association with integrins. In turn, the formation of stable integrin-tTG-PDGFR ternary complexes promotes PDGFR activation and downstream signaling, regulates the receptor turnover, and amplifies PDGFR-mediated cellular responses. These studies reveal a novel function of tTG in coupling the adhesion-mediated and growth factor-dependent signaling pathways. They suggest that this tTG activity might be involved in pro-inflammatory function of this protein in normal wound healing and tissue fibrosis (18), vascular remodeling (19), and tumor metastasis (20).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Expression Vectors

Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDFs) were from Clonetics/BioWhittaker. To generate NHDF cells with decreased tTG levels, they were infected with lentiviral vector pLKO.1 constructs harboring shRNAs against human tTG (Open Biosystems). The NIH3T3 cell lines in which expression of human tTG, tTG(C277-S), tTG deletion mutants, and FXIIIA is induced by mifepristone were described earlier (17).

Antibodies

mAbs CUB7402 and TG100 against tTG were from Neomarkers. The following antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (PDGFRβ, sc432; Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ, sc12906; Tyr(P)-716-PDGFRβ, sc19569; FGFR-1, sc123; epidermal growth factor receptor, sc03; β-tubulin, sc9104), Upstate Biotechnology (Tyr(P)-754-PDGFRα, 07-862), Cell Signaling Technology (PDGFRα, 3164; Tyr(P)-740-PDGFRβ, 3168; Tyr(P)-1009-PDGFRβ, 3124; Tyr(P)-1021-PDGFRβ, 2227; ubiquitin, 3936; Thr(P)-202-Tyr(P)-204-ERK1/2, 9101; Tyr(P)-418-src, 2113; Thr(P)-308-Akt1, 4056; Ser(P)-473-Akt1, 2337; Tyr(P)-542-Shp-2, 3751); R@D Systems (neutralizing antibody AF385 against the extracellular domains of human PDGFRβ is specific for the β isoform of the receptor and does not react with the α isoform; neutralizing antibody MAB765 against the extracellular domains of human FGFR-1); BD Pharmingen (rat anti-mouse/human β1 integrin, clone 9EG7, 553715; mouse mAb against human CD71 (transferrin receptor), 555534; c-Cbl, 610441); Sigma (Tyr(P)-397-focal adhesion kinase), and Millipore (β1-integrin cytoplasmic domain, AB1952). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Pierce. Cross-species-adsorbed donkey anti-mouse AlexaFluor 350, donkey anti-goat AlexaFluor 488, and donkey anti-rat AlexaFluor 594 antibodies were from Molecular Probes. 12-nm colloidal gold-labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG (715-205-150) and 6-nm colloidal gold-labeled donkey anti-goat IgG (705-195-147) were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories.

Adhesion and Antibody Clustering Experiments

To study adhesion-mediated activation of PDGFRβ, quiescent NIH3T3-vector, NIH3T3-tTG, and NIH3T3-tTG(C277-S) cells in serum-free medium were plated on fibronectin-coated plates for 0–360 min. For antibody clustering experiments, quiescent NHDF cells at 4 °C were treated for 45 min with 10 μg/ml primary antibodies against PDGFRβ, tTG, β1 integrin, low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1, transferrin receptor, or FGFR1, washed, and then incubated for another 45 min with 10 μg/ml secondary antibodies. Cells were lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with phosphatase inhibitors, and PDGFRβ phosphorylation at Tyr-751 was examined by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Coimmunoprecipitation, Chemical Cross-linking, and in Vitro Binding Assays

To analyze the association between tTG, PDGFRβ, and β1 integrins, a non-denaturing immunoprecipitation was performed with antibodies against these proteins after lysis of cells at 4 °C in 1% Triton X-100, 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and was followed by analysis of the immune complexes by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies to PDGFRβ, the cytoplasmic tail of β1 integrin (Millipore AB1952), or tTG. To detect the association of c-Myc-tagged tTG or its deletion mutants with PDGFRβ, a pulldown with anti-PDGFRβ antibody was followed by detection of bound material by immunoblotting with the antibody against c-Myc.

Chemical cross-linking was performed by incubation of NHDF cells and treated with 0.8 nm PDGF-BB for 0–90 min and with 2 mm DSP or DTSSP cross-linkers (Pierce) as described (17). Then the cells were lysed in 1% SDS, and the extracts were boiled and then reconstituted with 1% Triton X-100 in 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl. PDGFRβ was immunoprecipitated with antibody sc432 against the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor.

In in vitro binding experiments, purified recombinant human tTG (20 μg/ml in 0.1% Triton X-100, 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA) was incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with 10 μg of PDGFRα/Fc or PDGFRβ/Fc chimeras (R@D Systems) bound to Protein A-Sepharose. The beads were washed, and bound material was analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence and Immunoelectron Microscopy

To simultaneously visualize tTG, PDGFRβ, and β1 integrins on the surface of NHDF fibroblasts, quiescent or PDGF-BB-treated live non-permeabilized cells were triple-labeled with mouse anti-tTG mAb CUB7402, goat antibody specific for the PDGFRβ receptor isoform (R@D Systems, AF385), and rat mAb 9EG7 against β1 integrins (each at 20 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4 °C. Then the cells were washed, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with a mixture of secondary anti-mouse AlexaFluor 350 IgG, donkey anti-goat AlexaFluor 488 IgG, and donkey anti-rat AlexaFluor 594 IgG. To examine cell surface distribution of PDGFRβ in cells with normal or depleted levels of tTG, NHDF and NHDF-shtTG cells were plated in mixed culture. Double staining for tTG and PDGFRβ was performed by co-incubation of PDGF-BB-treated live non-permeabilized cells with a combination of 20 μg/ml mouse anti-tTG mAb CUB7402, goat antibody to PDGFRβ for 30 min at 4 °C, fixing with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, and staining with secondary anti-mouse AlexaFluor 594 IgG and donkey anti-goat AlexaFluor 488 IgG. Cells were viewed and photographed with 100× objective using Zeiss/Bio-Rad 200 confocal microscope. Images were acquired and digitally merged with Volocity software (Improvision).

For immunogold labeling and electron microscopy, NHDF cells on glass coverslips were treated with 2 nm PDGF-BB for 5 min at 4 °C. Live non-permeabilized cells were incubated at 4 °C with 20 μg/ml mouse anti-tTG mAb CUB7402 and goat antibody to PDGFRβ for 45 min, washed, and incubated for another 45 min with 20 μg/ml donkey anti-mouse IgG labeled with 12-nm gold and donkey anti-goat IgG labeled with 6-nm gold. The samples were fixed with 0.2% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline with 1% sucrose, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and embedded in Embed 812 epoxy resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Pale purple ultrathin (∼160 nm) sections were cut with LKB ultramicrotome and picked up on bare 200 mesh copper grids. Electron micrographs were taken using a Zeiss EM10 transmission electron microscope at 80 kV.

Biosynthetic Labeling of PDGFRβ

Metabolic labeling of NHDF and NHDF-shtTG fibroblasts with Tran35S label (MP Biomedicals) was performed as described (13, 17). After labeling, the cells were chased with regular growth medium for 0–360 min, PDGFRβ was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts, and the immune complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. To quantify the relative PDGFRβ amounts in each sample, gel slices containing the 35S-labeled protein bands were dissolved in 30% H2O2, and 35S radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting.

Immunoblotting

Quiescent or PDGF-BB-treated cells were lysed directly in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Proteins (20 μg per sample) were separated on 4–12% Bis/Tris Novex gels (Invitrogen), electroblotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with antibodies to the cytoplasmic domain of PDGFRα or PDGFRβ, their individual Tyr(P) residues, or several downstream signaling targets of the receptor (ERK1/2, Akt1, Shp-2, Src, focal adhesion kinase). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) were used for signal detection. The signals were quantified with NIH Image 1.63f software and averaged for each individual phospho site. For quantitative measurement of PDGFRβ activation by immunoblotting, cell proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to low background Odyssey nitrocellulose membrane (LiCor Biosciences). Receptor activation was determined with primary antibodies to Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ, PDGFRβ, and infrared dye-labeled IRDye 800CW anti-mouse and IRDye 680CW anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (LiCor Biosciences). Imaging and signal intensity quantification were performed with Odyssey Infrared two-laser Imaging System (Licor Biosciences).

PDGF Binding Assays

A dose-dependent binding of 0–2 nm 125I-PDGF-BB (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, 2200Ci/mmol) to 5 × 104 adherent quiescent adherent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells was determined at 37 °C for 5 min. Cell-associated radioactivity was measured in a gamma counter. Co-incubation with an excess of unlabeled PDGF-BB was used to determine and subtract nonspecific background binding.

Proliferation and Migration Assays

To analyze the effects of tTG on PDGF-dependent cell proliferation, NIH3T3-vector, NIH3T3-tTG, NHDF, and NHDF-shtTG fibroblasts were plated at 5 × 103 cells per well in 96-well microtiter plates in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 h. Subconfluent cells were starved for 48 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 0.1% fetal bovine serum. PDGF-BB (0–4 nm with or without 20 μg/ml PDGFR inhibitor AG1296) was added, and cell proliferation was determined 72 h later by the addition of the CellTiter 96® AQueous MTS-based Reagent (Promega, G3580) during the last 4 h of culture. The quantity of formazan product proportional to the number of metabolically active living cells was measured by absorbance at 490 nm and converted to cell numbers.

Chemotactic migration of NIH3T3-vector, NIH3T3-tTG, NHDF, and NHDF-shtTG fibroblasts (5 × 104 cells/insert) under serum-free conditions toward PDGF-BB gradient was studied in Transwells with 8-μm pores (Costar). Before plating the cells into the inserts, they were metabolically labeled with Tran35S label. PDGF-BB (0–4 nm) was added to the lower chambers. In some wells AG1296 (20 μg/ml) was added to both upper and lower chambers to inhibit PDGFR activation. After incubation for 12 h at 37 °C, cells transmigrated to the membrane undersurface were detached, and radioactivity was counted in a scintillation counter and converted to cell numbers.

RESULTS

tTG Promotes the PDGFR-integrin Association and Interacts with PDGFR on the Cell Surface

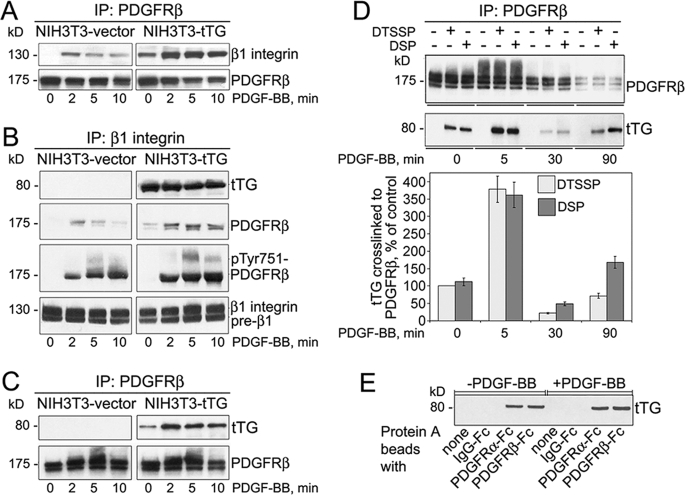

Integrins potentiate activation of several receptor-tyrosine kinases including PDGFR by soluble growth factors (1). tTG stably interacts with a significant fraction of integrins, causing their clustering on the membrane (17). Hence, we examined whether tTG modulates physical interaction between PDGFR and integrins in adherent fibroblasts in response to PDGF (Fig. 1, A and B). Earlier we described NIH3T3 fibroblasts lacking endogenous tTG in which expression of this protein is induced by mifepristone (17). No association of PDGFRβ with β1 integrins was revealed by co-immunoprecipitation in NIH3T3-vector cells, whereas PDGF induced a weak transient association between the two receptors (Fig. 1A, left panels). In contrast, significant amounts of β1 integrins were detected in the association with PDGFRβ in quiescent NIH3T3-tTG cells, whereas the formation of PDGFRβ-β1 integrin complexes was further increased by PDGF (Fig. 1A, right panels). Similar results were obtained in reciprocal experiments with pulldown of β1 integrins and detection of the associated PDGFRβ (Fig. 1B). Again, the association between PDGFRβ and β1 integrins was detected in quiescent NIH3T3-tTG but not in NIH3T3-vector cells, reflecting that the tTG-β1 integrin interaction did not depend on PDGF (Fig. 1B, right panels, 0 min). Moreover, a significant increase in the levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated (activated) PDGFRβ in association with β1 integrins was observed in PDGF-treated cells expressing tTG. These results indicate that tTG promotes complex formation between PDGFR and integrins and may regulate the joint PDGFR-integrin signaling.

FIGURE 1.

Cell surface tTG interacts with PDGFR and facilitates its association with integrins. A and B, cell surface tTG promotes the association of β1 integrins with PDGFR. Quiescent adherent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells were treated with 0.8 nm PDGF-BB for 0–10 min. PDGFRβ (A) or β1 integrins (B) were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell extracts, and the immune complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting for PDGFRβ and β1 integrin (A and B) as well as tTG and Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ, (B). C, PDGF stimulates the association of tTG with PDGFR. Association of tTG with PDGFRβ in quiescent and PDGF-BB-treated NIH3T3 cells was tested by immunoprecipitation of PDGFRβ from cell extracts and probing the immune complexes for tTG and PDGFRβ by immunoblotting. D, tTG interacts with PDGFR on the cell surface. Quiescent NHDF cells that express endogenous tTG were treated with 0.8 nm PDGF-BB for 0–90 min and at the end of this treatment incubated with membrane-impermeable DTSSP or membrane-permeable DSP cross-linkers. PDGFRβ was immunoprecipitated from SDS-denatured cell extracts, and the immune complexes were probed by immunoblotting for PDGFRβ and tTG. The amounts of tTG chemically cross-linked to PDGFRβ at different time points of PDGF treatment were expressed as percentages relative to that in unstimulated cells in the presence of DTSSP. E, tTG binds to the extracellular domains of PDGFR in vitro. Protein A beads alone, with bound human IgG-Fc, or with bound PDGFRα/Fc or PDGFRβ/Fc chimeras were incubated with 20 μg/ml purified tTG and washed, and bound tTG was detected by immunoblotting. Shown are the representatives of three independent experiments (A–E).

Because tTG binds to integrins and facilitates the PDGFR-integrin association, we examined whether tTG directly interacts with PDGFR (Fig. 1, C–E). Immunoprecipitation of PDGFRβ from extracts of NIH3T3-tTG fibroblasts showed its association with tTG in the quiescent cells, whereas the formation of complexes between the two proteins was significantly enhanced by PDGF-induced receptor activation (Fig. 1C).

Next, we evaluated whether this interaction occurs on the cell surface. Treatment of quiescent or PDGF-induced NHDFs that express endogenous tTG, PDGFRβ, and β1 integrins with membrane-impermeable DTSSP or membrane-permeable DSP chemical cross-linkers was followed by SDS denaturation of proteins and immunoprecipitation of PDGFRβ under denaturing conditions (Fig. 1D). It showed that tTG can be chemically cross-linked to this receptor, whereas no association between these proteins was seen upon denaturation without the cross-linkers. Notably, DTSSP was as efficient as DSP in the cross-linking of the two proteins, indicating that this interaction involves cell surface tTG and the extracellular region of PDGFRβ.

Finally, purified recombinant tTG was able to bind in vitro to the extracellular parts of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ fused to the Fc fragment of human IgG in the absence or presence of PDGF (Fig. 1E). Thus, tTG directly interacts with the extracellular domains of PDGFR and may promote the formation of ternary integrin-tTG-PDGFR complexes on the cell surface.

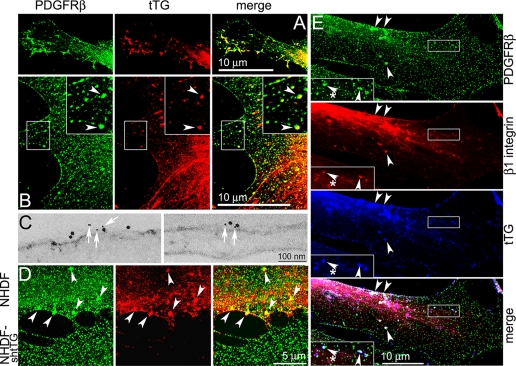

tTG Co-localizes with PDGFR on the Cell Surface and Causes Receptor Clustering

The above findings prompted us to compare localization patterns of tTG and PDGFRβ in PDGF-treated live non-permeabilized NHDF cells by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (Fig. 2, A–E). Although both proteins exhibited mostly uniform distribution over the surface of quiescent fibroblasts, they occasionally co-localized in small clusters in the lamellae (not shown). Early after PDGF stimulation, a robust co-localization of tTG and PDGFRβ was observed in numerous filopodia formed around cell edges (Fig. 2A). PDGF also induced a formation of distinct clusters that contained both PDGFRβ and tTG throughout the lamellae in NHDF fibroblasts (Fig. 2B, insets, arrowheads) and in NIH3T3 cells expressing exogenous tTG (supplemental Fig. 1). A close co-distribution of tTG and PDGFRβ on the plasma membrane of PDGF-stimulated cells was confirmed by immunogold labeling and electron microscopy (Fig. 2C). Therefore, tTG and PDGFR co-localize on the cell surface.

FIGURE 2.

A co-localization of tTG and PDGFR on the cell surface. Quiescent NHDF (A–E) and NHDF-shtTG (D) fibroblasts were treated with 2 nm PDGF-BB for 5 min. A, B, D, and E, immunofluorescence staining of live non-permeabilized cells and confocal microscopy. Images show co-localization of PDGFRβ and tTG in nascent filopodia (A) and in distinct large clusters throughout lamellae (B, insets, merged in yellow, arrowheads). C, Immunogold labeling of live non-permeabilized cells and electron microscopy. Note the proximity of small gold particles marking PDGFRβ (white arrows) to larger ones marking tTG on the plasma membrane of PDGF-treated NHDF cells. D, shRNA-mediated down-regulation of tTG leads to disappearance of large PDGFR clusters. NHDF cells that express endogenous tTG and their transfectants in which this protein was depleted by stable shRNA expression (NHDF-shtTG) were plated in mixed culture. Note a number of large PDGFR clusters containing tTG in the lamellae of NHDF fibroblasts (arrowheads, cell on the top) and the lack thereof in the tTG-deficient NHDF-shtTG fibroblasts (cell on the bottom). E, a co-localization of tTG with PDGFRβ and β1 integrins on the cell surface. Note distinct clusters containing all the three proteins on the dorsal cell surface (insets, merged in white, arrowheads). Bars: 10 μm (A, B, and E), 100 nm (C), or 5 μm (D).

The impact of tTG on PDGFRβ distribution was examined in a mixed culture of NHDF fibroblasts that either express or lack this protein (Fig. 2D). NHDFs harboring control scrambled shRNA contained large PDGFRβ clusters on their surface (NHDF, cell on the top, merged in yellow, arrowheads), whereas the cells in which endogenous tTG was depleted by shRNA (NHDF-shtTG, cell on the bottom), were devoid of prominent receptor clusters. Hence, tTG promotes PDGFR clustering on the cell surface.

Triple immunofluorescence labeling of live non-permeabilized PDGF-treated NHDF cells for PDGFRβ, β1 integrin, and tTG combined with confocal microscopy revealed partially overlapping localization of all the three proteins in small and large clusters on the dorsal surface (Fig. 2E, insets, merged in white, arrowheads). Notably, some membrane sites containing β1 integrins but no tTG were also lacking PDGFRβ (insets, merged in white, asterisks).

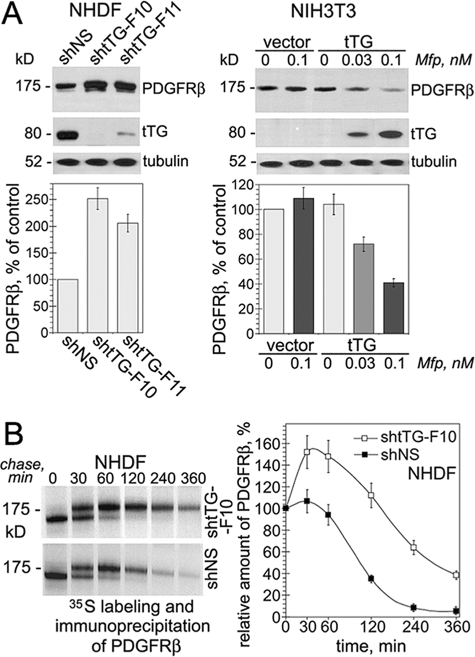

tTG Down-regulates Cellular PDGFR Levels Due to Accelerated Receptor Turnover

Next we examined the effects of tTG on the PDGFRβ levels (Fig. 3A). Stable expression of tTG shRNA in NHDF fibroblasts either abolished (shtTG-F10) or markedly decreased (shtTG-F11) the expression of endogenous tTG compared with its levels in the cells with control virus containing scrambled sequence (shNS, Fig. 3A, left panels). Importantly, the PDGFRβ levels were raised at least 2-fold in both NHDF populations expressing no or little tTG compared with that in the cells with control virus. To confirm that tTG regulates PDGFRβ levels, further experiments were performed with NIH3T3 fibroblasts in which tTG expression was induced by mifepristone (Fig. 3A, right panels). The induction of tTG in NIH3T3 fibroblasts caused a concentration-dependent decrease in steady state levels of PDGFRβ. The accumulation of tTG in these cells decreased the total and surface levels of the receptor, and this effect was independent of serum or PDGF (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). Thus, we concluded that tTG down-regulates steady state levels of PDGFR.

FIGURE 3.

Cell surface tTG down-regulates PDGFR levels by increasing receptor turnover. A, tTG decreases steady state levels of PDGFRβ. NHDF cells harboring shRNAs for tTG (shtTG-F10, shtTG-F11) or scrambled shNS sequence (upper left panels) and NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells treated with 0–0.1 nm mifepristone (upper right panels) were tested for the levels of tTG and PDGFRβ by immunoblotting with samples containing equal amounts of tubulin. The PDGFRβ levels in the transfectants were expressed as percentages of that in NHDF-shNS cells (lower left panel) or that in untreated NIH3T3-vector cells (lower right panel). B, effects of tTG expression on the turnover of PDGFRβ. NHDF cells expressing shtTG-F10 shRNA or scrambled shNS sequence were pulse-labeled with 200 μCi of Tran35S label for 30 min without PDGF-BB and then chased for the indicated times in the absence of growth factors. PDGFRβ was immunoprecipitated from SDS-denatured cell extracts containing 200 μg of total cell protein. The immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by fluorography. The amounts of PDGFRβ were defined by 35S scintillation counting and presented as percentages of those in the cells before the start of the chase. A and B, shown are the means ± S.D. for three independent experiments.

No difference in the PDGFRβ mRNA levels was observed between the fibroblasts lacking or expressing tTG (not shown). To study mechanisms of tTG-mediated PDGFRβ down-regulation, metabolic labeling and pulse-chase assays were performed in the absence of exogenous PDGF with NHDF fibroblasts lacking or expressing tTG (Fig. 3B). Immunoprecipitation of 35S-labeled PDGFRβ from cell extracts showed that tTG decreased the amounts of de novo synthesized PDGFRβ as early as 30 min after the start of the chase, and the receptor levels continued to decline faster thereafter. These results indicate that tTG promotes PDGFR turnover. Additional experiments showed that tTG accelerates PDGFR internalization from the cell surface and stimulates receptor degradation by promoting its ubiquitinylation, thereby down-regulating steady state cellular receptor levels (supplemental Fig. 3, A and B).

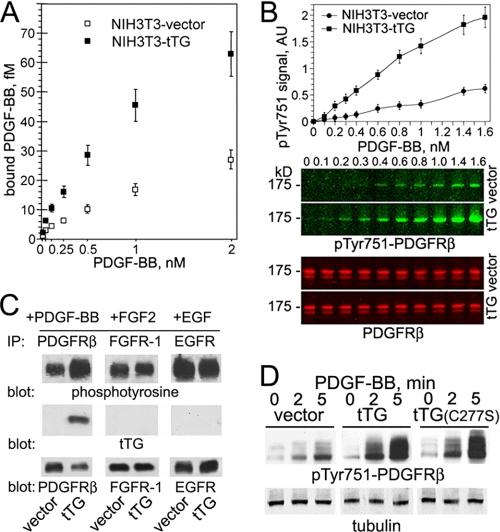

tTG Amplifies PDGF-mediated PDGFR Activation and Downstream Signaling

The ongoing results prompted us to test whether tTG affects the PDGFR interaction with the soluble ligand (Fig. 4A). Analysis of the 125I-PDGF-BB binding to quiescent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells revealed that cell surface tTG markedly increases the interaction of this growth factor with PDGFRβ (these cells express no PDGFRα).

FIGURE 4.

Expression of tTG in NIH3T3 fibroblasts increases PDGF-BB binding to cells and up-regulates PDGFR activation and signaling. A, cell surface tTG enhances the PDGF-PDGFR association. The binding of 0–2 nm 125I-PDGF-BB to 5 × 104 quiescent adherent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells was determined by measuring cell-associated radioactivity and expressed as the means ± S.D. with each measurement performed in triplicates. B, cell surface tTG amplifies PDGF-mediated PDGFRβ activation. Quiescent adherent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells were treated with 0–1.6 nm PDGF-BB for 2 min. Cell extracts containing equal amounts of PDGFRβ were analyzed for receptor activation by quantitative immunoblotting using rabbit antibody to PDGFRβ and mouse antibody to Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ. Infrared dye-labeled anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW IgG and anti-mouse IRDye 680CW IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Imaging and signal intensity quantification for Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ were performed with Odyssey infrared two-laser imaging system (LiCor). AU, fluorescence intensity, arbitrary units. C, tTG selectively binds and increases activation of PDGFR, but not of FGFR1 or epidermal growth factor receptor, in NIH3T3 cells. Quiescent adherent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells were treated with 2 nm PDGF-BB, FGF2 or epidermal growth (EGF) factor for 5 min. PDGFRβ (left panels), FGFR1 (middle panels), or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, right panels) was immunoprecipitated (IP) from 200 μg of cell extracts, and the immune complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting for phosphotyrosine (upper panels), tTG (middle panels), or these receptors (lower panels). D, the protein cross-linking activity of tTG is not required for its ability to promote PDGFR activation. Quiescent adherent NIH3T3-vector, NIH3T3-tTG, and NIH3T3-tTG(C277-S) fibroblasts were treated with 0.8 nm PDGF-BB for 0–6 min. Cell extracts normalized for equal amounts of tubulin were analyzed for PDGFRβ activation by immunoblotting using antibodies to Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ. A–D, shown are representatives of three independent experiments.

Because tTG co-localizes and interacts with PDGFR on the cell surface, increases PDGF binding, and down-regulates the receptor levels, we examined how it affects PDGFR signaling. PDGF-mediated activation of PDGFRβ in quiescent NIH3T3 fibroblasts lacking or expressing tTG was studied by detecting Tyr-751 phosphorylation with infrared dye-labeled secondary antibodies and quantitative imaging (Fig. 4B). A linear dose response was observed in both cell lines over a wide range of PDGF concentrations, yet when normalized to the total receptor levels, NIH3T3-tTG cells displayed a ∼4-fold increase in PDGFRβ activation compared with their counterparts lacking tTG. Further analysis of receptor activation showed a comparable increase in phosphorylation of several other PDGFRβ residues (Tyr-716, Tyr-740, Tyr-1009, and Tyr-1021) in NIH3T3-tTG compared with NIH3T3-vector cells (supplemental Fig. 4). Because induction of tTG in NIH3T3 fibroblasts did not alter the ligand-induced activation of FGFR-1 and GFR, this effect of tTG appeared to be specific for PDGFR (Fig. 4C). The catalytically inactive Cys-277-Ser tTG mutant was equally capable of increasing PDGF-BB-mediated receptor activation, thus indicating that the cross-linking activity does not contribute to this tTG function (Fig. 4D). Therefore, tTG amplifies ligand-dependent PDGFRβ activation because of increased receptor sensitization to soluble ligands.

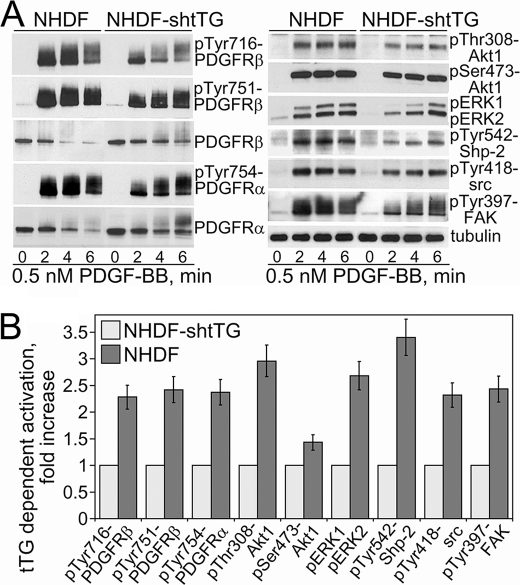

To prove that these alterations of PDGFR signaling are not caused by nonspecific effects of tTG overexpression, we examined the impact of tTG down-regulation in NHDFs on PDGF-mediated activation of PDGFR (Fig. 5). Evaluation of the early time course of PDGFRβ phosphorylation at Tyr-716 and Tyr-751 showed that tTG depletion in NHDF cells delayed and inhibited maximal receptor activation (Fig. 5, A, left panels, and B). Similar effects were observed with another PDGFR isoform, PDGFRα, which is co-expressed with PDGFRβ in these cells and is also activated by PDGF-BB. The changes in the activation of some PDGFR downstream targets essentially mirrored those of receptor activation (Fig. 5, A, right panels, and B). The activation of selected PDGFR signaling targets Akt1, ERK1/2, Shp-2, Src, and focal adhesion kinase was attenuated and inhibited by tTG down-regulation. Quantitative analysis with NHDF cells showed that some of them were highly sensitive to the tTG levels, with phosphorylation levels of Shp-2 phosphatase at Tyr-542 and Akt1 at Thr-308 decreasing the most in the absence of tTG (Fig. 5, A, right panels, and B). This suggests that the associated signaling pathways are primarily affected by tTG. Therefore, tTG depletion in NHDF fibroblasts down-regulates PDGF-dependent PDGFR activation and inhibits its downstream signaling. Together, these results indicate that tTG increases the PDGF-PDGFR association, raises the magnitude of PDGFR activation by the soluble ligand, PDGF, and amplifies the receptor downstream signaling.

FIGURE 5.

Down-regulation of tTG in NHDF fibroblasts attenuates and inhibits PDGFR signaling. Quiescent adherent cells expressing control scrambled shRNA (NHDF) or tTG shRNA (NHDF-shtTG) were treated with 0.5 nm PDGF-BB for 0–6 min. A, activation levels of PDGFR (left panels) and its downstream signaling targets (right panels) were determined by immunoblotting with antibodies to Tyr(P)-716-PDGFRβ, Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ, Tyr(P)-754-PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, PDGFRα, and Thr(P)-308-Akt1, Ser(P)-473-Akt1, pERK1/2, Tyr(P)-542-Shp-2, Tyr(P)-418-src, and Tyr(P)-397-focal adhesion kinase. All samples were normalized for equal amounts of tubulin. B, phospho-site signals were quantified, averaged, and expressed for NHDF cells as -fold activation over those in NHDF-shtTG cells. Shown are the means ± S.D. for three independent experiments.

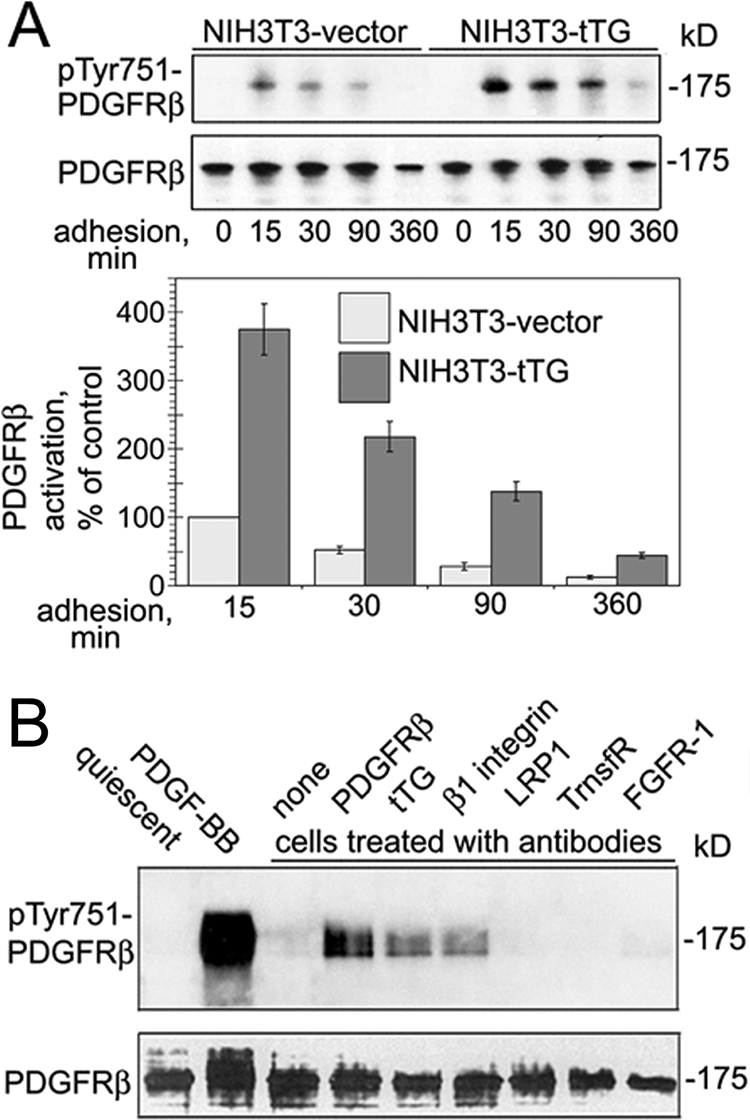

Cell Surface tTG Stimulates Integrin-mediated PDGFR Activation

Because cell surface tTG enhances integrin-dependent adhesion on fibronectin (13) and PDGFR is transiently activated by integrins in the absence of growth factors (2), we hypothesized that tTG may stimulate adhesion-mediated PDGFR activation in a ligand-independent manner. To provide a support for this concept, we tested the impact of tTG overexpression on adhesion-dependent PDGFRβ activation. As shown in Fig. 6A, PDGFRβ phosphorylation was markedly increased and prolonged upon adhesion of quiescent NIH3T3-tTG cells on fibronectin compared with that in NIH3T3-vector cells lacking tTG. Therefore, tTG amplifies integrin-mediated PDGF-independent activation of PDGFR.

FIGURE 6.

Clustering of cell surface tTG promotes PDGFR activation. A, Quiescent NIH3T3-vector and NIH3T3-tTG cells were plated on fibronectin for 0–360 min in serum-free medium without PDGF. The levels of integrin-dependent ligand-independent activation PDGFRβ in these cells at various times of adhesion were tested by immunoblotting for Tyr(P)-751-PDGFR, β and compared with that in NIH3T3-vector cells at 15 min of adhesion. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown. B, antibody-mediated clustering of tTG on the cell surface induces PDGFR activation. Quiescent adherent NHDF cells were treated at 4 °C with 20 μg/ml purified IgGs against PDGFRβ, tTG, β1 integrin, low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1), transferrin receptor (TrnsfR), and FGFR-1, washed, and then incubated with secondary IgGs. Alternatively, the cells were treated with 2 nm PDGF-BB for 2 min. None marks secondary IgGs alone. PDGFRβ activation was tested by immunoblotting for PDGFRβ and Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ in two independent experiments.

Clustering of Cell Surface tTG Triggers PDGFR Activation

To unequivocally prove a direct functional link between cell surface tTG and PDGFR signaling, we treated quiescent NHDF cells with antibodies to tTG, PDGFRβ, β1 integrins, and several other membrane receptors (Fig. 6B). Analysis of PDGFRβ activation revealed that clustering of either tTG or β1 integrins on the cell surface triggered tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGFRβ, albeit at lower levels than that caused by antibody-mediated receptor clustering. In contrast, no PDGFRβ activation was seen in the cells treated with antibodies to other receptors, including low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1), transferrin receptor (TrnsfR), or FGFR-1, all of which are abundantly expressed in these cells (Fig. 6B). The activation of PDGFR by antibody-mediated clustering of integrins or integrin-associated tTG indicates a physical association and functional interactions among PDGFR, tTG, and β1 integrins on the cell surface.

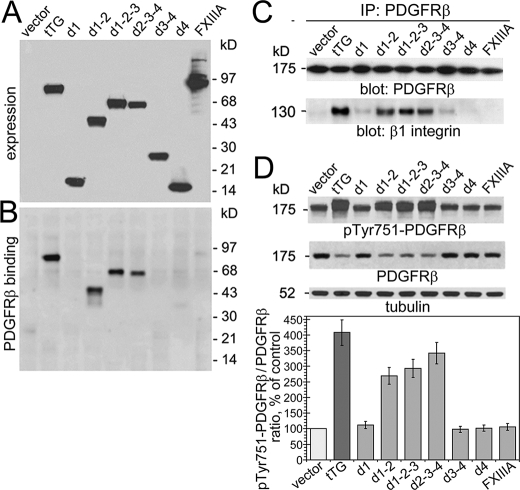

Interaction with the Second Domain of tTG Mediates the Association of PDGFR with Integrins and the Regulation of PDGFR Expression and Signaling

To test whether the tTG-mediated alterations of PDGFR signaling are because of direct interaction of the receptor with tTG on the cell surface, we employed a set of previously characterized tTG deletion mutants (22) to compare their binding to PDGFR, impact on the association of PDGFR with integrins, and effects on receptor expression and activation (Fig. 7). Pulldown experiments with purified recombinant PDGFRβ/Fc chimera and extracts of NIH3T3 cells containing the tTG deletion mutants showed that only the ones containing the second (catalytic) domain of tTG bind the receptor (Fig. 7, A and B). Moreover, co-immunoprecipitation experiments with extracts of NIH3T3 cells expressing tTG mutants showed that only those that contained the second domain of tTG were capable of mediating the PDGFRβ-β1integrin association (Fig. 7C). Finally, the same set of tTG mutants displayed the capacity to promote PDGFRβ activation and down-regulate the receptor levels (Fig. 7D). Altogether, these data suggest that the tTG-dependent effects on PDGFR activation and signaling are because of bridging the PDGFR and β1 integrins by tTG. Therefore, the interaction of PDGFR with tTG via its second domain mediates the formation of ternary complexes with integrins and regulates the receptor function.

FIGURE 7.

The interaction with the second (catalytic) domain of tTG mediates its effects on PDGFR expression and signaling. A, expression of tTG deletion mutants with COOH-terminal c-Myc tags in NIH3T3 fibroblasts. The expression levels of full-length tTG, its domains, and FXIIIA transglutaminase were examined by immunoblotting with antibody to c-Myc. B, the interaction of tTG deletion mutants with PDGFR. Extracts of NIH3T3 transfectants that express tTG, its deletion mutants, or FXIIIA were incubated with PDGFRβ-Fc chimeric protein immobilized on protein A beads. The material bound to the beads was analyzed by immunoblotting with antibody to c-Myc. C, the interaction with the second domain of tTG mediates the PDGFR/integrin association. PDGFRβ was immunoprecipitated (IP) from the extracts of PDGF-BB-treated NIH3T3 transfectants that express tTG or its deletion mutants, and the resulting immune complexes were probed by immunoblotting for PDGFRβ or β1 integrin. D, the effects of tTG deletion mutants on PDGFR expression and activation. Quiescent adherent cells were treated with 1.6 nm PDGF-BB for 2 min. Extracts of NIH3T3 transfectants were normalized for tubulin levels and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to Tyr(P)-751-PDGFRβ and PDGFRβ. The relative PDGFRβ activation levels were defined as the ratios of receptor phosphorylation at Tyr-751 and the receptor levels and expressed as percentages of that in NIH3T3-vector cells. A–D, shown are representative results of three independent experiments.

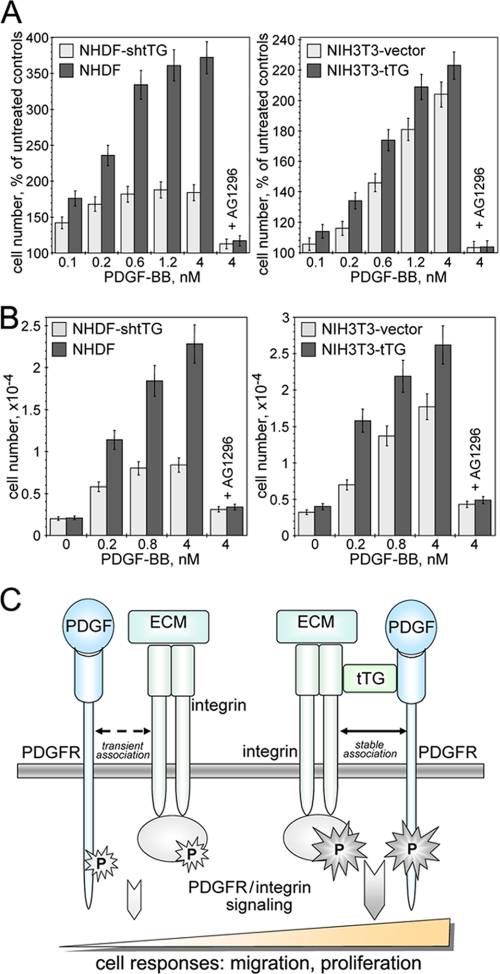

tTG Promotes PDGF-mediated Proliferation and Migration of Fibroblasts

PDGF acts as a powerful mitogen and motogen for mesenchymal cells (5). Because our studies show the ability of tTG to amplify PDGFR signaling, we examined the effects of this protein on the key PDGF-mediated cell responses such as proliferation and migration (Fig. 8). Analysis of NIH3T3 and NHDF cell proliferation revealed that tTG significantly enhanced the mitogenic action of PDGF for both types of fibroblasts (Fig. 8A). Likewise, PDGF-mediated chemotactic migration was markedly increased for both types of tTG-expressing fibroblasts compared with their counterparts lacking tTG (Fig. 8B). Importantly, the observed stimulatory effects of tTG on PDGF-dependent growth and migration of fibroblasts were blocked by specific and potent inhibitor of PDGFR tyrosine kinase activity AG1296. Consequently, tTG promotes the migration and proliferation of fibroblasts driven by PDGF/PDGFR-mediated signaling.

FIGURE 8.

tTG is required for efficient PDGF-mediated proliferation and migration of fibroblasts. A and B, quiescent adherent NIH3T3 and NHDF cells lacking or expressing tTG were treated with 0–4 nm PDGF-BB. Some samples contained 10 μm specific PDGFR inhibitor AG1296. A, PDGF-dependent cell proliferation over 72 h was quantified with CellTiter™ 96-well MTS-based assay (Promega). The cell numbers were expressed as percentages of those for untreated cells. B, PDGF-dependent chemotactic migration of 5 × 104 35S-labeled cells through 8-μm membrane pores was studied in Transwells™. After 12 h, transmigrated cells were removed from the bottoms of the filters; radioactivity was counted and converted to cell numbers. A and B, shown are the means ± S.D. for two independent experiments performed with each measurement performed in triplicate. C, a proposed role for integrin-associated cell surface tTG in the regulation of PDGFR signaling function. Integrins and PDGFR transiently interact, and their association is required for efficient signal transduction after PDGFR activation by PDGF and some other growth factors (left panel). tTG promotes the interaction of PDGFR with integrins by bridging the two receptors on the cell surface and stabilizing their association (right panel). The formation of stable ternary integrin-tTG-PDGFR complexes alters PDGFR membrane distribution and turnover, enhances its activation because of increased receptor clustering and ligand binding, and up-regulates downstream signaling, resulting in amplification of the key PDGFR-dependent cell responses.

DISCUSSION

Cell-matrix adhesion and integrin function emerged as an essential controller of PDGFR and other receptor-tyrosine kinases; however, the molecular details of this regulation remain elusive (1, 2). In this work, we present evidence that integrin-associated tTG acts as a physical link between integrins and PDGFR as well as a potent activator of both adhesion-mediated and growth factor-induced PDGFR signaling. We propose a unifying model that implicates tTG in the regulation of PDGFR function (Fig. 8C). It implies that tTG facilitates the transient association of PDGFR with integrins by bridging the two receptors on the cell surface and amplifies joint PDGFR/integrin signaling from the membrane to cell interior. Our previous work showed that on the surface of various cells all tTG is present within stable 1:1 complexes with integrins (13). Although it is not easy to ascertain stoichiometry within the ternary PDGFR-tTG-β1 integrin complexes, our results indicate that upon stimulation with PDGF, ≥95% of total cellular PDGFR becomes associated with β1 integrins in NIH3T3-tTG cells, whereas this fraction does not exceed ∼30% of the receptor levels in NIH3T3 cells lacking tTG. Together with other results, these data strongly suggest that the association of PDGFR with β1 integrins via tTG on the cell surface sensitizes the cells to PDGF and possibly other soluble ligands of this receptor, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (21). Importantly, this modulation of PDGFR function by tTG promotes PDGF-dependent cell migration and proliferation and is likely to stimulate other cell responses driven by synergistic PDGFR/integrin signaling, such as cell survival and differentiation.

It has to be noted that we were unable to reproduce the effects of tTG expression on the PDGFR function with exogenous purified tTG added to cultured cells. This is likely because of the inability of exogenous tTG to bind to cell surface integrins (13). Because the association with integrins is important for the regulation of PDGFR function, the lack of binding to β1 integrins prevents the ability of exogenous tTG to bridge these two receptors and activate PDGFR. Yet, we showed previously that that tTG interacts with under-glycosylated precursors of the β1 integrins, which have yet to be exported to the cell surface, indicating that these complexes are formed inside the cells, likely during integrin biosynthesis (13). Alternatively, tTG might interact with integrins present inside the endosomal vesicles undergoing recycling to the cell surface. Our unpublished results show an association of cytoplasmic tTG with endosomes and enrichment of tTG within the perinuclear recycling endosomal compartments. Together, these observations suggest an importance of currently undefined co-exportation mechanism(s) in the functioning of β1 integrin-tTG complexes on the cell surface.

The molecular details underlying the PDGFR activation by integrin-associated tTG remain to be determined. Nonetheless, we envision that direct interactions of tTG with integrins (13) and PDGFR (this study) together with the propensity of tTG to oligomerize (22) increase the avidity of PDGFR by clustering the receptor and enhance ligand binding. A physical proximity of integrins and PDGFR due to their bridging by tTG should facilitate the recruitment of numerous signaling and adapter proteins involved in the joint signaling and thereby stimulate the response to PDGF. Initial analysis of selected PDGFR signaling targets revealed that their activation is affected by tTG. Several lines of evidence suggest that the function of Src homology 2 domain-containing Shp-2 phosphatase, a key upstream regulator of both integrin- and PDGFR-mediated signaling (4), might be altered because of increased association of PDGFR with integrins mediated by tTG. First, our results indicate a greater PDGF-dependent increase in Shp-2 phosphorylation compared with other targets in the cells expressing tTG. Furthermore, Shp-2 regulates PDGFR signaling by acting as a sensor of cell-matrix interactions (2, 23, 24), and cell surface tTG enhances cell-ECM adhesion. Finally, forced Shp-2 targeting to lipid rafts, the membrane domains in which tTG is present (25, 26) and integrins and PDGFR accumulate, promotes cell adhesion, and spreading and activates focal adhesion kinase and RhoA (27), all reported features of tTG overexpression phenotype (13). Therefore, by mediating the integrin-PDGFR association, tTG is likely to activate the integrin-SHPS1-Shp2-PDGFR-RasGAP-Ras signaling cascade. Unbiased phosphoproteomic approach and targeting selected components of this pathway will help to test this hypothesis.

The occurrence of distinct PDGFR clusters co-localized with β1 integrins in the cells expressing tTG indicates that formation of stable ternary integrin-tTG-PDGFR complexes alters the membrane distribution of PDGFR. The enhancement of integrin-PDGFR association by tTG might regulate the partitioning of PDGFR between integrin-containing focal complexes and other membrane microdomains, including lipid rafts/caveolae and non-raft fractions. In turn, this tTG-mediated redistribution of PDGFR on the surface is likely to affect receptor turnover. The endocytosis/ubiquitinylation machinery may preferentially recognize PDGFR complexes with integrins and tTG, thereby down-regulating PDGFR levels by accelerated internalization and degradation. Finally, the increased PDGF binding to cells expressing tTG and elevated magnitude of receptor activation upon exposure to soluble ligand indicate that the interaction with tTG on the cell surface increases PDGFR affinity to soluble ligands. Therefore, integrin-associated tTG profoundly affects several principal aspects of the PDGFR signaling function. Upcoming studies should characterize the tTG-PDGFR interaction, delineate the tTG-binding site on the receptor and define the impact of this interaction on its ligand binding affinity.

The identified functional interactions among β1 integrins, PDGFR, and tTG are not likely to operate in development. Although the former two receptors are critical for multiple developmental processes (5, 28), and the corresponding knock-outs are early embryonic lethal, tTG appears late in development, and the protein is dispensable for embryogenesis (12). Yet, we envision that the physical and functional interactions of these proteins are essential not only in cultured cells but also in vivo in various pathologic processes, particularly in the vasculature. Notably, up-regulation of PDGFR signaling function (29) and increased expression of the α5β1 integrin (30) are the hallmarks of vascular inflammation and smooth muscle neoplasia. Intriguingly, recent studies also show a robust up-regulation of tTG during vasculo-proliferative conditions in the vessel wall (18). Thus, we expect that tTG might serve as a potent amplifier of PDGFR signaling function and associated cell responses in vascular smooth muscle during vascular remodeling, atherogenesis, and restenosis.

Our findings also provide significant mechanistic insights into recently recognized involvement of tTG in several other pathophysiologic processes, including tissue fibrosis, inflammation, and tumor metastasis. Sensitization of cells to the action of PDGF and other growth factors that signal through PDGFR may represent a major novel function of tTG during inflammation. In addition, up-regulation of tTG biosynthesis and surface expression by PDGF and other growth factors (12) might be an essential part of the stimulatory autocrine/paracrine signaling axis operating via PDGFR. Accordingly, the reported contribution of tTG to dermal wound healing and angiogenesis (31) could be explained at least in part by the activation of PDGFR signaling via cell surface tTG. Furthermore, a significant increase in tTG expression during liver and renal fibrosis (32), atherosclerosis (18, 33), and in metastatic cancer cells of diverse tissue origin (19) all suggest an essential role of this protein in the in vivo processes that involve hyperactivation of PDGFR signaling and promote cell survival, proliferation, and migration leading to inflammation and tissue fibrosis (5). Finally, the ability of autoantibodies to PDGFR, found in patients with systemic sclerosis (34) and chronic graft-versus-host disease (35), to stimulate receptor activation, downstream signaling, and promote fibrosis due to enhancement of collagen synthesis may be mimicked by autoantibodies to tTG present in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis (36). Impending analysis of the tTG function in the regulation of PDGFR signaling in vivo should provide important information regarding the role of this protein in inflammatory responses.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM62895 (to A. M. B.) and HL50784 and HL54710 (to D. K. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- GFR

- growth factor receptor

- PDGFR

- platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor

- tTG

- tissue transglutaminase

- NHDF

- normal human dermal fibroblasts

- DSP

- dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate)

- DTSSP

- dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidyl) propionate

- Bis/Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FGFR

- fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamada K. M., Even-Ram S. ( 2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 75– 76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundberg C., Rubin K. ( 1996) J. Cell Biol. 132, 741– 752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron W., Decker L., Colognato H., ffrench-Constant C. ( 2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 151– 155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMali K. A., Balciunaite E., Kazlauskas A. ( 1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19551– 19558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heldin C. H., Westermark B. ( 1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 1283– 1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostman A. ( 2004) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15, 275– 286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferns G. A., Raines E. W., Sprugel K. H., Motani A. S., Reidy M. A., Ross R. ( 1991) Science 253, 1129– 1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn T. A. ( 2008) J. Pathol. 214, 199– 210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raines E. W., Koyama H., Carragher N. O. ( 2000) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 902, 39– 51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tallquist M., Kazlauskas A. ( 2004) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15, 205– 213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto S., Teramoto H., Gutkind J. S., Yamada K. M. ( 1996) J. Cell Biol. 135, 1633– 1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorand L., Graham R. M. ( 2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 140– 156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akimov S. S., Krylov D., Fleischman L. F., Belkin A. M. ( 2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 825– 838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akimov S. S., Belkin A. M. ( 2001) Blood 98, 1567– 1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akimov S. S., Belkin A. M. ( 2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 2989– 3000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belkin A. M., Akimov S. S., Zaritskaya L. S., Ratnikov B. I., Deryugina E. I., Strongin A. Y. ( 2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18415– 18422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janiak A., Zemskov E. A., Belkin A. M. ( 2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1606– 1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verderio E. A., Johnson T. S., Griffin M. ( 2005) Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 38, 89– 114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakker E. N., Pistea A., Vanbavel E. ( 2008) J. Vasc. Res. 22, 271– 278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verma A., Guha S., Diagaradjane P., Kunnumakkara A. B., Sanguino A. M., Lopez-Berestein G., Sood A. K., Aggarwal B. B., Krishnan S., Gelovani J. G., Mehta K. ( 2008) Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2476– 2483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball S. G., Shuttleworth C. A., Kielty C. M. ( 2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 489– 500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S., Cerione R. A., Clardy J. ( 2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 2743– 2747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rönnstrand L., Arvidsson A. K., Kallin A., Rorsman C., Hellman U., Engström U., Wernstedt C., Heldin C. H. ( 1999) Oncogene 18, 3696– 3702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekman S., Kallin A., Engström U., Heldin C. H., Rönnstrand L. ( 2002) Oncogene 21, 1870– 1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zemskov E. A., Janiak A., Hang J., Waghray A., Belkin A. M. ( 2006) Front. Biosci. 11, 1057– 1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zemskov E. A., Mikhailenko I., Strickland D. K., Belkin A. M. ( 2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 3188– 3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacalle R. A., Mira E., Gomez-Mouton C., Jimenez-Baranda S., Martinez-A. C., Manes S. ( 2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 277– 289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheppard D. ( 2000) Matrix Biol. 19, 203– 209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boucher P., Gotthardt M., Li W. P., Anderson R. G., Herz J. ( 2003) Science 300, 329– 332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barillari G., Albonici L., Incerpi S., Bogetto L., Pistritto G., Volpi A., Ensoli B., Manzari V. ( 2001) Atherosclerosis 154, 377– 385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haroon Z. A., Hettasch J. M., Lai T. S., Dewhirst M. W., Greenberg C. S. ( 1999) FASEB J. 13, 1787– 1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grenard P., Bresson-Hadni S., El Alaoui S., Chevallier M., Vuitton D. A., Ricard-Blum S. ( 2001) J. Hepatol. 35, 367– 375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haroon Z. A., Wannenburg T., Gupta M., Greenberg C. S., Wallin R., Sane D. C. ( 2001) Lab. Invest. 81, 83– 93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baroni S. S., Santillo M., Bevilacqua F., Luchetti M., Spadoni T., Mancini M., Fraticelli P., Sambo P., Funaro A., Kazlauskas A., Avvedimento E. V., Gabrielli A. ( 2006) N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2667– 2676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svegliati S., Olivieri A., Campelli N., Luchetti M., Poloni A., Trappolini S., Moroncini G., Bacigalupo A., Leoni P., Avvedimento E. V., Gabrielli A. ( 2007) Blood 110, 237– 241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molberg Ø., Sollid L. M. ( 2006) Trends Immunol. 27, 188– 194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.