Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Age-associated insulin resistance may underlie the higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes in older adults. We examined a corollary hypothesis that obesity and level of chronic physical inactivity are the true causes for this ostensible effect of aging on insulin resistance.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We compared insulin sensitivity in 7 younger endurance-trained athletes, 12 older athletes, 11 younger normal-weight subjects, 10 older normal-weight subjects, 15 younger obese subjects, and 15 older obese subjects using a glucose clamp. The nonathletes were sedentary.

RESULTS

Insulin sensitivity was not different in younger endurance-trained athletes versus older athletes, in younger normal-weight subjects versus older normal-weight subjects, or in younger obese subjects versus older obese subjects. Regardless of age, athletes were more insulin sensitive than normal-weight sedentary subjects, who in turn were more insulin sensitive than obese subjects.

CONCLUSIONS

Insulin resistance may not be characteristic of aging but rather associated with obesity and physical inactivity.

There is a widespread assertion that aging leads to insulin resistance (1–3), which is in turn fundamental to the etiology and higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes in older adults (4–6). The evidence supporting the concept of age-associated insulin resistance, however, is contradicted by reports demonstrating that insulin resistance may not be associated with aging per se but rather with lifestyle patterns linked with aging, such as a reduced physical activity (7) and obesity (8). Thus, it is not clear whether insulin resistance is characteristic of aging or, alternatively, whether obesity and/or physical inactivity underlie this “aging” effect. The purpose of this study was to help detangle the effects of aging, obesity, and chronic exercise on insulin resistance by comparing younger and older subjects matched for level of obesity and chronic physical activity.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Men and women aged 35.4 ± 1.1 years (range 24–47) (“younger”) and 66.9 ± 0.8 years (range 60–75) (“older”) were recruited through advertisement in the Pittsburgh area. We studied 7 younger endurance-trained athletes (YA, 6 men/1 woman), 12 older athletes (OA, 10 men/2 women), and 11 younger normal-weight sedentary (YN, 6 men/5 women), 10 older normal-weight sedentary (ON, 5 men/5 women), 15 younger obese sedentary (YO, 7 men/8 women), and 15 older obese sedentary (OO, 7 men/8 women) subjects. The athletes were currently performing endurance exercise ≥5 days/week. Sedentary was defined as exercise ≤1 day/week. All subjects were weight stable for at least 6 months, were nonsmokers, and were in general good health. Subjects were excluded if they had type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or uncontrolled hypertension and if they were taking any chronic medications known to affect glucose homeostasis. All volunteers gave their informed written consent, and the protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Insulin sensitivity was measured as rate of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal (Rd) during a 4-h hyperinsulinemic (40 mU · m−2 · min−1)-euglycemic clamp performed during standardized conditions (i.e., after an overnight fast and period of no exercise; i.e., in the 36–48 h before the clamp), as described elsewhere (9). We used stable isotope dilution methods [6,6-2H2]glucose (0.22 μmol/kg, 17.6 μmol/kg prime) to account for residual hepatic glucose production. Fat-free mass (FFM) and fat mass were assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (GE Lunar Prodigy and Encore 2005 software version 9.30; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, MI). Peak aerobic capacity (Vo2peak) was measured using a graded exercise protocol as described previously (10).

Differences among the six study groups were analyzed with a between-subject one-way ANOVA. Post hoc tests were performed with the Tukey-Kramer HS adjustment. All analyses were done using JMP version 5.0.1.2 for Macintosh (SAS, Cary, NC) with an α level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Within each age-group, age was similar among athletes, normal-weight, and obese groups. BMI was higher in the obese groups (33.8 ± 0.6 and 33.7 ± 0.54 kg/m2 for YO and OO, respectively) compared with the normal- weight groups (23.5 ± 0.6 and 24.4 ± 0.7 kg/m2 for YN and ON, respectively) and the athletes (24.7 ± 0.8 and 23.6 ± 0.6 kg/m2 for YA and OA, respectively). Similar patterns were observed for the relative proportion of body fat, except that the ON had a higher (P < 0.05) proportion of body fat than the YN. Cardiorespiratory fitness (Vo2peak) was higher in YA (72.8 ± 3.7 ml · min−1 · kgFFM−1) than OA (54.0 ± 1.9 ml · min−1 · kgFFM−1), who were both higher than normal-weight sedentary (43.4 ± 1.92 for YN and 40.3 ± 2.0 ml · min−1 · kgFFM−1 for ON) and obese sedentary (39.6 ± 1.7 for YO and 30.7 ± 1.7 ml · min−1 · kgFFM−1 for OO) subjects.

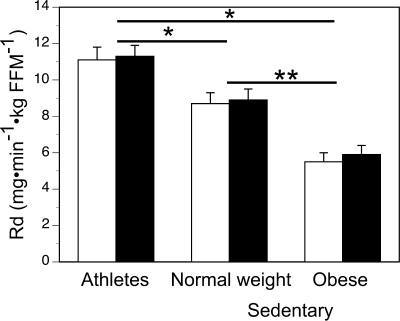

Among athletes, normal-weight subjects, or obese subjects, insulin sensitivity (Rd) was not different according to age (Fig. 1 ). Regardless of age, athletes were more insulin sensitive than normal-weight sedentary subjects, who in turn were more insulin sensitive than obese subjects, even after adjusting for fat mass or the proportion of body fat. Similar to peripheral insulin sensitivity, hepatic insulin sensitivity (that is, residual hepatic glucose production) during the clamp was similar in older and younger subjects within athlete, normal-weight, and obese groups (data not shown). Both younger and older obese subjects, however, had greater (P < 0.01) residual hepatic glucose production.

Figure 1.

Insulin sensitivity in athletes and sedentary normal-weight and obese, young, and old individuals. Bars are mean rates of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal (Rd), and error bars are SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer HS adjustment: *difference (P < 0.05) between athletes and either normal-weight or obese, **significant difference (P < 0.05) between normal weight and obese. □, younger; ■, older.

CONCLUSIONS

The key finding was that insulin resistance is not an inherent feature of older age, but that obesity and physical inactivity underlie the purported insulin resistance of aging. While previous studies have examined whether insulin resistance is associated with older age (11,12), they either limited their observations to only normal-weight subjects, or they did not objectively account for physical fitness or physical activity. Therefore, our results significantly expand on these studies by comparing, for the first time, insulin resistance in younger and older subjects across groups of normal-weight, obese, and athletic subjects, who were expected to have a wide range of insulin sensitivity.

We clearly demonstrate that after accounting for both obesity and high level of chronic physical activity, aging per se is not associated with insulin resistance. Moreover, hepatic insulin resistance, measured by residual hepatic glucose production during the clamp, was also similar between younger and older subjects. Thus, the similar peripheral insulin sensitivity between older and younger subjects was not confounded by residual hepatic glucose production.

Our study was not designed to determine potential mechanisms for insulin resistance associated with age, obesity, or physical inactivity, nor does it rule out possible differences in the etiology of insulin resistance between older and younger individuals. While the study of highly trained athletes is useful to compare younger and older subjects at high levels of both physical activity and insulin sensitivity, it does not allow us to extrapolate these findings to subjects with more moderate physical activity levels that correspond to current physical activity recommendations (13). However, these data are consistent with studies demonstrating significant improvements in insulin sensitivity induced by moderate exercise in older subjects (7). Therefore, although more modest levels of physical activity can improve insulin sensitivity in this population, further investigations are needed to determine whether older and younger obese adults experience similar improvements in insulin sensitivity with weight loss and moderate exercise programs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the following grants: American Diabetes Association Clinical Research Award (B.H.G.), NIH RO1 AG20128 (B.H.G.), NIH GCRC (5M01RR00056), and Obesity Nutrition Research Center (1P30DK46204).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Parts of this work were submitted for presentation at the annual scientific meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine in May 2009.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1. Defronzo RA: Glucose intolerance and aging: evidence for tissue insensitivity to insulin. Diabetes 1979; 28: 1095– 1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fink RI, Kolterman OG, Griffin J, Olefsky JM: Mechanisms of insulin resistance in aging. J Clin Invest 1983; 71: 1523– 1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, Dziura J, Ariyan C, Rothman DL, DiPietro L, Cline GW, Shulman GI: Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science 2003; 300: 1140– 1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reaven GM: Banting lecture 1988: Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988; 37: 1595– 1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS, Goldstein DE, Little RR, Wiedmeyer HM, Byrd-Holt DD: Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 518– 524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H: Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1047– 1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dube JJ, Amati F, Stefanovic-Racic M, Toledo FG, Sauers SE, Goodpaster BH: Exercise-induced alterations in intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance: the athlete's paradox revisited. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294: E882– E888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelley DE, Goodpaster B, Wing RR, Simoneau JA: Skeletal muscle fatty acid metabolism in association with insulin resistance, obesity, and weight loss. Am J Physiol 1999; 277: E1130– E1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amati F, Dube JJ, Stefanovic-Racic M, Toledo FG, Goodpaster BH: Improvements in insulin sensitivity are blunted by subclinical hypothyroidism. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009; 41: 265– 269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amati F, Dube JJ, Shay C, Goodpaster BH: Separate and combined effects of exercise training and weight loss on exercise efficiency and substrate oxidation. J Appl Physiol 2008; 105: 825– 831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lanza IR, Short DK, Short KR, Raghavakaimal S, Basu R, Joyner MJ, McConnell JP, Nair KS: Endurance exercise as a countermeasure for aging. Diabetes 2008; 57: 2933– 2942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrannini E, Vichi S, Beck-Nielsen H, Laakso M, Paolisso G, Smith U: Insulin action and age: European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabetes 1996; 45: 947– 953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA, 1996 [Google Scholar]