Abstract

Child and adolescent depression often go untreated with resulting adverse effects on academic success and healthy development. Depression screening can facilitate early identification and timely referral to prevention and treatment programs. Carried out in school settings, universal screening can reduce disparities in service utilization by extending the reach of detection and intervention to children who otherwise have limited access. However, unless confidentiality and informed choice are assured, benefits of universal screening may be offset by loss of individual rights. Implementation of a school-based depression screening program raises the controversial question of how to obtain informed parental consent. During implementation of a depression screening program in an urban school district in the Pacific Northwest, the district’s parental consent protocol changed from passive to active, providing a natural experiment to examine differences in participation under these two conditions. Compared to conditions of parent information with option to actively decline (passive consent), when children were required to have written parental permission (active consent), participation was dramatically reduced (85% to 66%). In addition, under conditions of active consent, non-participation increased differentially among student subgroups with increased risk for depression. Successful implementation of school-based mental health screening programs warrants a careful read of community readiness and incorporation of outreach activities designed to increase understanding and interest among target groups within the community. Otherwise, requiring active parental consent may have the unwanted effect of reinforcing existing disparities in access to mental health services.

Literature Review

Although childhood depression has been associated with poor school performance, failure to complete school, drug use, and suicide (1–3), most children with major depressive disorder or sub-threshold depressive symptoms do not receive treatment (4–6). School-based programs have great potential to reduce disparities in service utilization and health status by extending the reach of effective interventions to children who otherwise have limited access to treatment or preventive care (7–9). Many school-based programs that address adolescent depression or suicide-risk utilize universal or targeted screening to identify potential at risk students (7,10–13). There are a number of factors that make depression an appropriate screening target. The prevalence among children is high (2.5–8.3%) (14), and inexpensive, accurate, and easy to administer screening tools are available (15,16). Most importantly, early intervention can be beneficial (17–20). Early intervention is predicated upon early detection, and without active screening, detection of depression and other emotional health problems that manifest with internalizing symptoms is difficult, especially in younger children (21). A recent study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine named depression screening as among the top 25 preventive services offering the most health benefit for the health care dollar (22). Yet considerable backlash was generated by recommendations from the President’s New Freedom Commission to implement universal mental health screening in public schools (9).

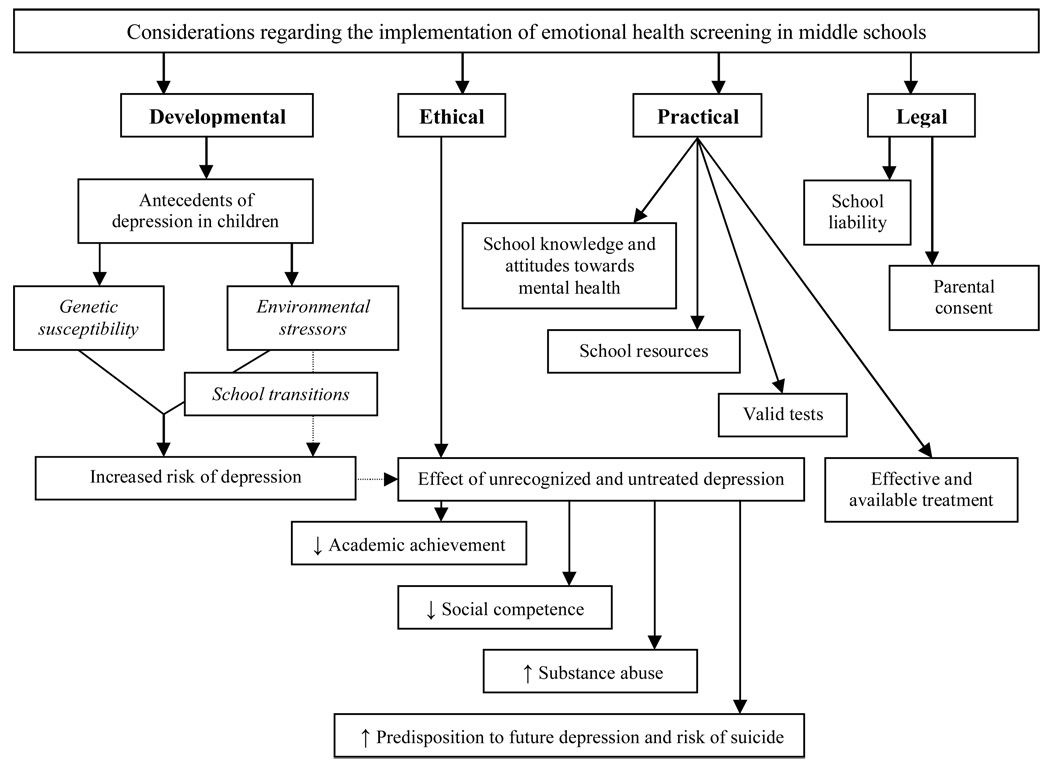

As illustrated in Figure 1, implementation of universal depression screening in a school setting is carried out within a complex contextual framework of developmental, ethical, practical and legal considerations. Ethically, untreated and undiagnosed depression and other emotional health conditions may have critical implications for a child’s development. Practical considerations include the degree to which the school district administration, school board and community recognize the role that emotional health plays in successful school performance. Other practical issues include the availability of local resources for the administration of screening tests and the provision of appropriate follow-up care. Finally, legal questions have been raised by the public and the press regarding voluntary participation in screening, the dissemination and use of screening results, and the interests and agendas of proponents and funders. Successful implementation of screening programs requires safeguards to assure confidentiality and informed choice, without which program benefits may be offset by loss of individual rights (23). Pivotal in debates about school-based screening is the issue of how parent and child consent/assent are obtained.

Figure 1.

Framework for Implementation of Universal Depression Screening in Middle Schools

In general, minors (legally defined as any person under the age of 18 in 47 states (24) are required to have parental permission to receive medical treatment. However, a child can be considered a minor in the eyes of the law, but still be allowed to consent for specific health services in a limited number of situations. Although ages vary by state, minors in most states may consent to reproductive health care (related to sexual assault, rape, pregnancy and STD services), HIV testing and counseling, mental health care, and drug or alcohol related services without parental notification (24). Boonstra, et. al have emphasized the importance of providing these types of confidential services to adolescents, since minors tend not to seek services for such sensitive health concerns, if they must notify their parents (25).

At present, consent for students to participate in school-based emotional health programs is obtained using different approaches, as dictated by the school district in which the program is being implemented (8,9,12–14,29,36–37). The choice of approach is generally based on a district’s interpretation of the Protection of Pupil Rights Act (PPRA), put into effect by the federal government in the 1970s. The PPRA states that, “No student shall be required … to submit to a survey, analysis or evaluation that reveals information concerning … mental or psychological problems of the student or the student’s family” (28). The Act states that these stipulations “do not apply to any physical examination or screening that is permitted or required by an applicable State law, including physical examinations or screening that are permitted without parental notification.” How this Act is to be applied with regard to depression screening or when students are asked questions about “feeling unhappy” or “thinking that bad things would happen” is open to interpretation.

Districts may decide to implement school-based health programs under conditions of passive parental consent, in which parents are provided with information and given the option to decline, or active parental consent, in which written parental permission is required before the child can participate. Under passive consent, parental non-response is interpreted as consent, whereas under active consent, non-response is interpreted as decline.

Studies that compare participation rates under differing conditions have shown that requiring active consent lowers student participation (29,30) and systematically excludes specific demographic and high risk groups (31–33). For example, in a trial of a gang prevention program delivered to middle-school students recruited from 18 schools across the U.S., active parental consent protocols affected student participation differentially with respect to race, parental education, family structure, and parental level of school commitment (31). Another study found that use of active parental consent for participation in a survey of adolescent alcohol use led to differential under-representation of target groups of adolescents at high risk for drinking (33). While these studies demonstrated that use of active consent led to systematic exclusion of students at risk of disruptive behavior problems from programs that target these conditions, little is known as to whether participation in programs targeting internalizing problems would be similarly affected.

Reported here are the results of a natural experiment that afforded an opportunity to examine participation in a school-based depression screening and early intervention program under differing consent procedures. Midway through implementation, a change in school district policy altered requirements for student participation from passive to active parental consent. This paper addresses the questions of how the requirement of active parental consent affected overall program participation and whether it led to differential exclusion of children who were at increased risk for depression.

Methods

Subjects

Study setting

Universal depression screening was conducted by the University of Washington’s (UW) Developmental Pathways Project (DPP) in 6th grade classrooms in four public middle schools in the Seattle School District, during the fall semesters of 2002 and 2003. Students who screened positive for depression risk were evaluated at school by a child mental health professional who worked with students and parents to facilitate referrals to school and community-based programs.

A total of 1,000–1,100 6th grade students are enrolled annually across the four schools which are located in distinct geographic and demographic areas of the city. With respect to race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, students in participating schools were representative of students throughout the district. All 6th grade students enrolled when the screening program was offered were eligible for participation unless a disabling condition precluded their understanding and completion of the questionnaire. A more extensive discussion of the larger project and methodology is presented elsewhere (34). Study methods and recruitment strategies were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee and the Director of the Office of Research, Evaluation and Assessment of the Seattle Public Schools.

Conditions of the natural experiment

Due to a decision by the Seattle School District legal counsel, the passive parental consent protocol employed during implementation of screening in 2002 was changed in 2003 to an active protocol requiring written parental permission for participation.

Instruments

A screening questionnaire was administered to students under the supervision of trained DPP field staff. Basic demographic and family information was collected on the first page followed by 30 items from the Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (MFQ) (35) for 11–18 year olds, which has been well validated in community samples (36). MFQ questions were developed based on criteria for major depression and dysthymia in children in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (37). The MFQ covers affective, melancholic, vegetative, cognitive and suicidal aspects of depression as specified by DSM-III-R criteria in the two weeks prior to taking the survey. Three questions regarding suicide were removed due to their sensitive nature and the informality of a classroom setting.

Sources of Data for the Present Study

Data from the DPP screening questionnaire were used in the present study, from which a measurement of depression-vulnerability was derived based on an MFQ score of 20 or greater. Response values for missing MFQ items were imputed by assigning missing items the average value of all the completed MFQ items for that particular student. Additional information on all students was obtained from school records and included gender, race/ethnicity (from parent report to school) and program (regular education, gifted, Early Language Learner (ELL), and Special Education).

Procedures

The change from passive to active parental consent necessitated the use of somewhat different recruitment strategies. The unique and common recruitment elements across the two study years are described below.

Recruitment strategies consistent across both years

In both years, written assent was obtained from students. Colorful screening posters specific to each school were placed in classrooms and hallways. Every effort was made include students in ELL) and Special Education classrooms. A brief paragraph describing the project was translated into the primary non-English languages (e.g. Spanish, Somali, Vietnamese, Tagalog, Chinese) spoken by families at each school and was sent to parents. The project contracted with language interpreters to telephone non-English-speaking parents and address their questions. During the 2 weeks following official screening day, project staff returned to the school and made three attempts to screen students who had been absent.

YEAR 1 (2002): “Passive” consent, parental information with option to decline

Two weeks prior to the initial screening day an introductory letter from the school principal and an information sheet was sent home to parents of all eligible students. Parents who did not want their children to participate in screening were asked to return a self-addressed postcard included with the information packet. One week prior to screening day, DPP staff hosted a 6th grade assembly or presentations to 6th grade homerooms to announce the upcoming screening day and provide an opportunity for students to ask questions.

YEAR 2 (2003): “Active” consent, parental information with written parental permission

A letter of introduction from the school principal, an information sheet and a parental consent form were included in the school enrollment packets. Each year these packets are sent to parents of all students in the district and contain mandatory emergency contact information that must be updated and returned during the first week of the school year. In each of the four schools, study investigators attended the most important PTA meeting of the year or equivalent (e.g. 6th grade back to school night) in which they introduced the screening project to parents and described the opportunity for students to participate. DPP also placed announcements in school newsletters.

To discourage non-response, students who returned their consent form, regardless of the parent’s response (consent or decline), received a small prize. The week prior to screening day, DPP staff visited homerooms to redistribute parental consent forms and answer questions. All students who returned parental consent forms by screening day, regardless of response, were entered in a raffle for a larger prize. The weekend prior to screening DPP staff made phone calls to all parents who had not yet responded.

Data Analyses

A Chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of students who participated in the depression screening program across the two study years. Next, a series of analytic steps were taken to address the question of whether, under conditions of active consent, students with high depression risk were selectively excluded from participation. Within gender, racial, school, school program subgroups of students, the proportion decline in participation from 2002 to 2003 and the proportion of positive screens in 2002 were calculated, to assess whether subgroups that experienced a marked decline in participation also had a high proportion of positive screens. Second, incorporating information from students screened in 2002, logistic regression analyses were used to fit an equation that would predict each student’s probability of screening positive on the basis of her/his gender, race/ethnicity, school, and educational program. Finally, with the resulting equation the mean predicted probability of screening positive for depression among 2003 non-respondents, participants, and declines was calculated. One-way analysis of variance was conducted to test for significant differences among these subgroups.

Results

Of the 1,011 enrolled students who were eligible to participate in screening in the fall of 2002, the parents of 69 (6.8%) declined to allow their children to participate; 58 students (5.7%) declined participation; 12 (1.2%) were absent on screening day and on the subsequent make-up days; and 11(1.1%) of students were excluded because their parents did not receive the notification letter and therefore had no opportunity to decline. A total of 861 (85.2%) eligible students participated. Of the 1,021 students eligible for screening in 2003, the parents of 215 (21.1%) declined to allow their children to participate, 16 students (1.6%) declined participation; and 117 (11.5%) parents did not return a permission form. A total of 672 (65.8%) eligible students participated. A significantly lower proportion of students participated under conditions of active than under conditions of passive consent (65.8% vs. 85.2%; p < 0.001).

As shown in Table 1, the magnitude of decline in participation and the proportion of students who screened positive for depression differed by student race/ethnicity, by school, and by educational program. The subgroups with the highest proportion of positive screeners in Year 1 tended to be those with the greatest decline in participation in Year 2. For example, in Year 1 African American students were significantly more likely than Caucasian students to screen positive for depression (OR = 2.09; 95% CI = 1.18 – 3.70) and experienced a disproportionately greater decline in participation from Year 1 to Year 2 (a decrease of 30.1% among African American students, compared to a decrease of 9.8% among Caucasian students).

Table 1.

Screening Participation and Depression Screening Status, by School, Educational Program, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity, and Year (2002 & 2003).

| SCREENING PARTICIPATION |

DEPRESSION STATUS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2003 | 2002 | 2003 | ||||||

| N | % of eligible students screened |

N | % of eligible students screened |

change in % participation |

N | % screening positive for depression a |

N | % screening positive for depression a |

|

| Total | 861 | 85.2 | 672 | 65.8 | −19.4 | 118 | 13.7 | 99 | 14.7 |

| School | |||||||||

| A | 188 | 80.3 | 137 | 57.3 | −23 | 17 | 9.0 | 39 | 28.5 |

| B | 350 | 85.4 | 311 | 77.2 | −8.2 | 38 | 10.9 | 28 | 9 |

| C | 126 | 88.1 | 78 | 54.5 | −33.6 | 27 | 21.4 | 11 | 14.1 |

| D | 197 | 87.9 | 146 | 61.6 | −26.3 | 36 | 18.3 | 21 | 14.4 |

|

Educational program |

|||||||||

| Regular | 594 | 83.4 | 478 | 63.8 | −19.6 | 79 | 13.3 | 71 | 14.9 |

| Gifted | 98 | 89.9 | 83 | 76.9 | −13 | 3 | 3.1 | 12 | 14.5 |

| ESL | 71 | 91 | 45 | 69.2 | −21.8 | 14 | 19.7 | 5 | 11.1 |

| SBD b | 10 | 90.9 | 7 | 77.8 | −13.1 | 3 | 30 | 1 | 14.3 |

| Other special education |

88 | 87.1 | 59 | 64.8 | −22.3 | 19 | 21.6 | 10 | 16.9 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 394 | 84.2 | 329 | 66.6 | −17.6 | 56 | 14.2 | 54 | 16.4 |

| Male | 467 | 86 | 343 | 65 | −21 | 62 | 13.3 | 45 | 13.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Caucasian | 340 | 87.6 | 297 | 78.4 | −9.2 | 32 | 9.4 | 29 | 9.8 |

| African American | 225 | 83.6 | 139 | 53.5 | −30.1 | 43 | 19.1 | 41 | 29.5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 206 | 83.4 | 149 | 59.4 | −24 | 33 | 16 | 18 | 12.1 |

| Hispanic | 77 | 86.5 | 69 | 64.5 | −22 | 8 | 10.4 | 10 | 14.5 |

| Native American/ Alaska Native |

13 | 72.2 | 17 | 70.8 | −1.4 | 2 | 15.4 | 1 | 5.9 |

An MFQ score of 20 or higher was considered “positive” for depression

Seriously Behaviorally Disturbed (SBD)

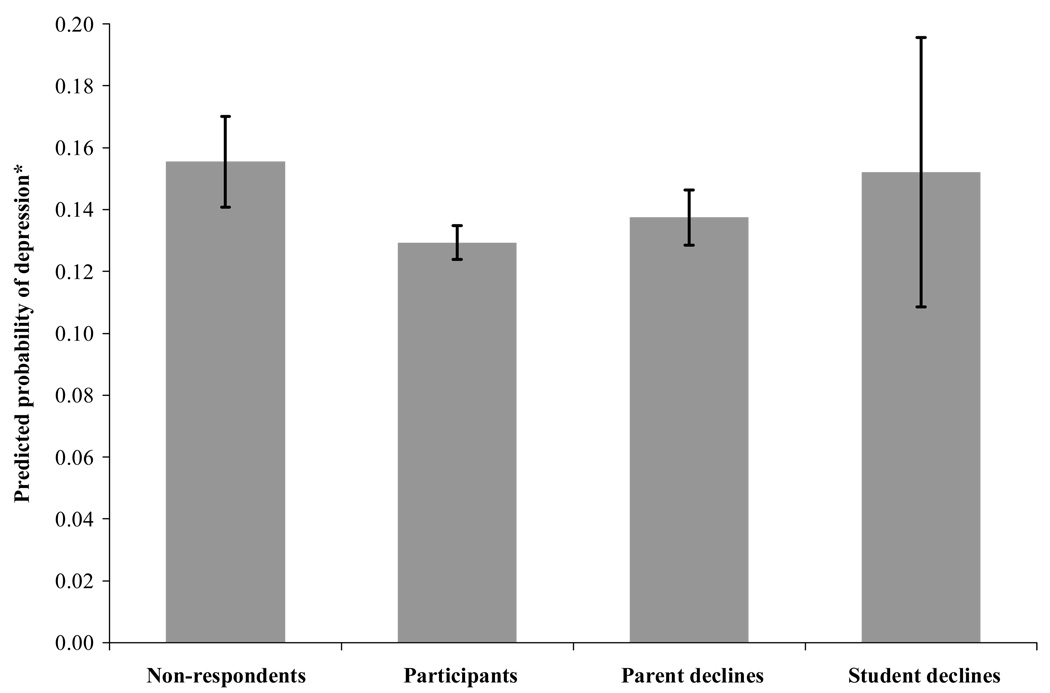

As shown in Figure 2, compared to other Year 2 participants and non-participants, the predicted probability of screening positive for depression was significantly higher for students who in Year 2 were excluded from participation due to non-response (F = 4.844, df = 3, p = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Predicted Probability of Depression, by Consent Status, 2003

* Percent predicted to score 20 or higher on the MFQ (and 95% confidence intervals) based on school, educational program, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Discussion

This natural experiment demonstrated that participation in a depression screening program fell markedly under conditions of active, as compared to passive parental consent, and that the decline in participation was not equivalent across subgroups of students or across schools. Under conditions of active consent, participation by groups of students with a higher likelihood of screening positive for depression was differentially reduced. These findings are consistent with other research showing differential exclusion of high risk students when active parental permission is required for participation in school-based programs (31–33).

A comment is warranted about a perplexing study finding. Despite the disproportionate reduction in participation in groups at increased risk of screening positive, the percentage of students who screened positive for depression did not, as might be expected, decrease from Year 1 to Year 2. Instead, it increased (though not significantly) from 13.7% to 14.7%. There are two plausible explanations for this finding, neither of which can be substantiated with the data available. One explanation is a cohort effect, (i.e., the 2003 6th grade cohort had worse emotional health than the 2002 6th grade cohort). The second explanation is a variation of “the ecological fallacy” in that, although subgroups of students at high risk of depression showed a more precipitous decline in participation, individual students at risk of depression within these subgroups may have selectively participated. The equivalence in the proportions of positive screens among participating students in Years 1 and 2 is consistent with Eaton, et. al.’s finding that despite general drops in participation under conditions of active, as compared with passive parental consent, the prevalence of adolescent risk behavior in surveyed students from 143 schools across the U.S. did not change (30).

This study of participation in a depression screening program has a number of limitations. Parental attitudes towards emotional health screening and consent differ by state and school district such that these findings may have limited external validity. Also the internal validity of our findings is limited by the naturalistic (non-randomized) conditions under which the study was conducted. Factors other than the change in consent procedure could have influenced student participation between the 2 years of the study. For example, there was a change in principals at Schools B and C which could have influenced school policy and attitudes towards screening. School B, which did not experience a decline in participation, was exceptional for a number of reasons. School administration and parents demonstrated a clear interest in the issue of childhood depression. In 2003 the primary investigators were invited to lead a mental health workshop for all faculty and staff and to make a presentation on adolescent emotional development at a well-attended 6th Grade Parent Night. A summary of these talks was published in the school newsletter. This experience underscores the importance of active efforts to foster community readiness, regardless of the requirements for parental consent.

In examining factors related to participation in screening and to emotional health status, the classification system used for race/ethnicity may have been too crude, as it made distinct between immigrant and native-born families. Nearly 27% of students screened reported both parents being born outside of the U.S. Combining African immigrants with native-born African Americans and Asian immigrants with native-born Asian Americans within the same racial categories may be inappropriate. The emotional health status and likelihood of participation in emotional health screening of immigrants and non-immigrants of the same race is likely to differ (38).

Reasons for parental response or non-response were not assessed. Lack of information about and appreciation of the role of emotional health in academic performance, fear of stigma, mistrust of mental health interventions, and language barriers may have contributed to decisions or lack thereof. Just as different strategies may be needed to encourage participation among families from different races, additional targeted outreach is needed for families who are not native English speakers and for families from cultural groups that adhere to specific attributions about and interventions for childhood emotional health problems.

In conclusion, implementation of school-based emotional health screening programs warrants careful consideration of community readiness to apply public health solutions to children’s emotional health problems. Questions regarding consent procedures for emotional health screening in students, the use of screening results, and the interests and agendas of funders should be addressed openly. School districts planning to implement mental health programs should be aware that requiring active parental consent may run at cross purposes to the goal of extending the reach of mental health care to underserved populations and may have the unwanted effect of reinforcing existing disparities in access to mental health services. Alternatives to active parental consent, such as an active/passive consent protocol have been proposed. This approach uses active consent during round one and passive consent in round two, allowing students whose parents did not respond to choose to participate while allowing parents who do not want their children to participate multiple opportunities to decline (39).

Increased awareness of how academic success “rests on a foundation of social-emotional competencies” (p. 303) (40) should be fostered among children themselves, their parents, school administrators, and policy makers. Effective social marketing strategies that are tailored to the needs and attitudes common in specific cultural subgroups of the population and that engender interest among key school leaders are critical to furthering this process. Child and adolescent depression are prevalent, and school-based programs have great potential to address social and economic disparities in access to interventions designed to improve children’s emotional health status and academic success.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by R01-MH63711 from the National Institutes of Mental Health and Drug Abuse. The authors wish to thank the Seattle children and parents who participated in the Developmental Pathways Project.

References

- 1.Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(1):133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(11):1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vander Stoep A, Weiss NS, Kuo ES, Cheney D, Cohen P. What proportion of failure to complete secondary school in the US population is attributable to adolescent psychiatric disorder? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2003;30(1):119–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02287817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, Moore RE, Cohen P, Alegria M, et al. Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(9):1081–1090. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00010. discussion 1090–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angold A, Costello EJ, Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Erkanli A. Impaired but undiagnosed. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(2):129–137. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute of Mental Health. Blueprint for change: research on child and adolescent mental health. Washington, DC: National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgoup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shochet IM, Dadds MR, Holland D, Whitefield K, Harnett PH, Osgarby SM. The efficacy of a universal school-based program to prevent adolescent depression. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30(3):303–315. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spielberger J, Haywood T, Schuerman J, Richman H. Third-year implementation and second-year outcome study of the Children's Behavioral Health Initiative. Palm Beach County, Florida: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago; 2004. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final Report. Rockville, MD: 2003. DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3832. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson EA, Eggert LL, Randell BP, Pike KC. Evaluation of indicated suicide risk prevention approaches for potential high school dropouts. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:742–752. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCauley E, Vander Stoep A, Pelton J. The High School Transition Study: Preliminary Results of a School-based Randomized Controlled Trial. A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base; Paper presented at the 17th Annual Research Conference; 2004; Tampa, FL: University of South Florida; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spence SH, Sheffield JK, Donovan C. Preventing adolescent depression: An evaluation of the Problem Solving for Life Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):3–13. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowalenko N, Rapee RM, Simmons J, Wignall A, Hoge R, Whitefield K, et al. Short-term effectiveness of a school-based early intervention program for adolescent depression. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;10(4):493–507. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services. Additional DHHS Protections for Children Involved as Subjects in Research. 1983. In; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeBlanc JC, Almudevar A, Brooks SJ, Kutcher S. Screening for adolescent depression: Comparison of the Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale with the Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2002;12(2):113–126. doi: 10.1089/104454602760219153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(6):726–737. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington R, Rutter M, Fombonne E. Developmental pathways in depression: Multiple meanings, antecedents, and endpoints. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:610–616. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Roth C, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(9):877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: Psychopharmacological treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1082–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaycox LH, Reivich KJ, Gillham J, Seligman ME. Prevention of depressive symptoms in school children. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32(8):801–816. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vander Stoep A, Pelton J, Kuo E. Methodological considerations in identification of a target group for preventive interventions. Society for Research in Child Development; Paper presented in the symposium Methodological Considerations in Implementing Preventive Interventions to Reduce Risk for Depression in Adolescence; 2005; Atlanta, GA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maciosek VM, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities Among Effective Clinical Preventive Services: Results of a Systematic Review and Analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyne J, Thompson R, Palmer S, Kagee A, Maunsell E. Should we screen for depression? Caveats and potential pitfalls. Applied & Preventative Psychology. 2000;9:101–121. [Google Scholar]

- 24.English A. Guidelines for adolescent health research: legal perspectives. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17(5):277–286. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(95)00183-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boonstra H, Nash E. Minors and the right to consent to health care. Issues Brief (Alan Guttmacher Inst) 2000;2:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aseltine RH, Jr, DeMartino R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):446–451. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(CPPRG) CPPRG. Merging universal and indicated prevention programs: the Fast Track model. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:913–927. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.20 USCA § 1232h. Protection of pupil rights

- 29.Pokorny SB, Jason LA, Schoeny ME, Townsend SM, Curie CJ. Do participation rates change when active consent procedures replace passive consent. Eval Rev. 2001;25(5):567–580. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eaton DK, Lowry R, Brener ND, Grunbaum JA, Kann LP. assive versus active parental permission in school-based survey research: Does the type of permission affect prevalence estimates of risk behaviors? Evaluation Review. 2004;28:564–577. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04265651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esbensen F, Miller MH, Taylor TJ, He N, Freng A. Differential attrition rates and active parental consent. Evaluation Review. 1999;23(3):316–335. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9902300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tigges BB. Parental consent and adolescent risk behavior research. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(3):283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frissell KC, McCarthy DM, D'Amico EJ, Metrik J, Ellingstad TP, Brown SA. Impact of consent procedures on reported levels of adolescent alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vander Stoep A, McCauley E, Thompson K, Kuo ES, Herting J, Stewart DG, Anderson CA, Kushner S. Universal screening for emotional distress during the middle school transition. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2005;13(4):213–223. doi: 10.1177/10634266050130040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angold A, Costello EJ. Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (MFQ) Durham, NC: Developmental Epidemiology Program, Duke University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thepar A, McGuffin P. Validity of the shortened Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in a community sample of children and adolescents: a preliminary research note. Psychiatry Res. 1998;81(2):259–268. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messer SC, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kushner S, Vander Stoep A. Mental Health of Sixth Grade Children of Immigrants in Seattle, WA. Seattle: University of Washington; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esbensen FA, Deschenes EP, Vogel RE, West J, Arboit K, Harris L. Active parental consent in school-based research. An examination of ethical and methodological issues. Eval Rev. 1996;20(6):737–740. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9602000605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias MJ, Zins JE, Graczyk PA, Weissberg RP. Implementation, sustainability, and scaling up of social-emotional and academic innovations in public schools. School Psychology Rev. 2003;32(3):303–320. [Google Scholar]