Abstract

There is a growing need for cellular imaging with fluorescent probes that emit at longer wavelengths to minimize the effects of absorption, autofluorescence and scattering from biological tissue. In this paper a series of new environmentally-sensitive hemicyanine dyes featuring amino(oligo)thiophene donors have been synthesized via aldol condensation between a 4-methylpyridinium salt and various amino(oligo)thiophene carboxaldehydes, which were, in turn, obtained from amination of bromo(oligo)thiophene carboxaldehyde. Side chains on these fluorophores impart a strong affinity for biological membranes. Compared with benzene analogues, these thiophene fluorophores show significant red shift in the absorption and emission spectra, offering compact red and near-infrared emitting fluorophores. More importantly, both the fluorescence quantum yields and the emission peaks are very sensitive to various environmental factors such as solvent polarity or viscosity, membrane potential, and membrane composition. These chromophores also exhibit strong nonlinear optical properties, including two-photon fluorescence and second harmonic generation, which are themselves environmentally-sensitive. The combination of long wavelength fluorescence and nonlinear optical properties make these chromophores very suitable for applications that require sensing or imaging deep inside tissues.

Introduction

The ultimate goal in the field of biomedical imaging is to visualize cellular structures and functions with submicrometer spatial and submillisecond temporal resolutions. Fluorescence has been playing a leading role in this direction due to its high sensitivity and the ability to target specific molecules or cellular compartments.1 Imaging cells and biological tissues can often be complicated by the autofluorescence of natural chromophores such as NADH. Scattering and absorption are two other major interfering factors, especially in thick tissues. Probes, emitting in the so-called medical spectral window (650–900 nm), can potentially minimize these interferences and offer high signal/background ratios. Furthermore, because of the inverse 4th power relationship between light scattering and wavelength, long wavelength probes permit deep tissue detection of optical signals.2,3

The last decade has witnessed significant progress in long-wavelength bioprobes, from conventional organic dyes4–7 to fluorescent proteins,8,9 quantum dots,10,11 and lanthanide complexes.12,13 Cyanine dyes have been dominating Near-IR imaging applications and some of them even have been approved by the FDA (e.g., indocyanine green, Chart 1). The absorption peak of a symmetric cyanine red-shifts ~100 nm for every vinylene extension and can be calculated using a classical free electron gas model.14

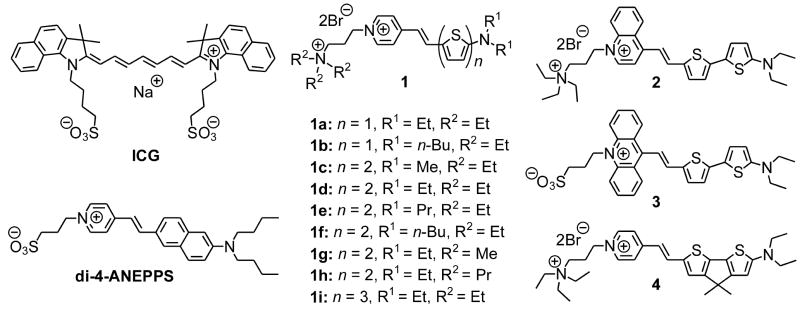

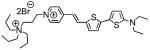

CHART 1.

Structures of Indocyanine green (ICG), di-4-ANEPPS, and amino(oligo)thiophene-based hemicyanines (1–4).

Hemicyanine chromophores (e.g., di-4-ANEPPS, Chart 1) have one quaternary nitrogen within a heterocycle and one acyclic tertiary nitrogen end group; they generally absorb at much shorter wavelengths than the corresponding cyanines, which typically have a pair of symmetrically arrayed heterocyclic end groups. Unlike symmetric cyanines, hemicyanines have distinct donor and acceptor groups so that there is significant electron shift from donor to acceptor ends of the chromophore upon photo-excitation; thus, they encompass an important class of push-pull chromophores. Our laboratory has been exploring the chemistry and photophysics of these hemicyanines (also called amino-styryl dyes) for many years.15–20 Their optical properties lead to many useful traits such as environmentally sensitive spectra,16,21 good nonlinear optical signals22,23 and voltage-sensitive fluorescence.16,20 These properties, largely absent in symmetrical cyanines, make the hemicyanine chromophores ideally suited for incorporation into biosensor probes. The development of longer wavelength hemicyanines with compact structures can therefore have significant impact in the field of biophotonics and live cell imaging.

Conventional vinylene extension met with only limited success in making long-wavelength hemicyanines and suffered from problems of product stability and synthetic difficulty.4,20 An alternative strategy is to use thienylene, which represents a good balance between stability and wavelength-shifting ability in comparison with phenylene and vinylene.24,25 Indeed, thienylene has proven effective in red-shifting voltage sensitive dyes (VSD) while preserving voltage sensitivities.4,26 In this paper, we describe a new group of hemicyanines featuring the amino(oligo)thiophene-pyridinium structure (Chart 1), including detailed syntheses, systematic structure-property relationships, environment sensitivities, and general applicability as long wavelength fluorescent sensors of cell membrane physiology.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

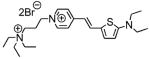

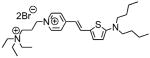

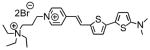

Unlike aniline, amino(oligo)thiophenes are extremely sensitive to air and mostly known in disubstituted forms. More often than not, there are electron-withdrawing groups attached to help stabilize them. In our series of dyes, the N-alkylpyridinium moiety serves this purpose and concomitantly supplies as π-electron acceptor to complete the push-pull chromophore. Shown in Scheme 1 is a general route for the synthesis of amino(oligo)thiophene-based hemicyanines from commercially available bromo(oligo)thiophene carboxaldehydes. The first step is an aromatic nucleophilic substitution (SNAr) reaction with a secondary amine, bypassing unstable primary amino(oligo)thiophenes. For n = 1 (see Scheme 1), direct amination in water27 proceeds well and is preferred for its simplicity; for higher homologs, CuI catalyzed amination28,29 is necessary to obtain the desired products. Here the aldehyde group not only facilitates the amination reaction but also stabilizes the product, which is the required intermediate for the subsequent aldol condensation reactions with appropriate salts, i.e., 4-methylpyridinium, 4-methylquinolinium, or 10-methylacridinium salts. The two-step yield critically depends on the bulkiness of substituent R1, ranging from ~70% for methyl to ~10% for n-butyl.

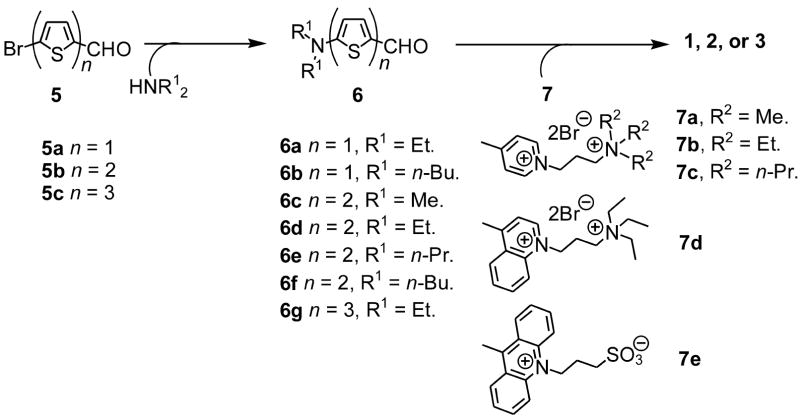

SCHEME 1.

A general route to amino(oligo)thiophene-based hemicyanines

It should be noted that (oligo)thiophene derivatives like 6 have been of considerable interest as donor moieties in organic nonlinear optical materials30 and photorefractive31 materials. However there are only a few reports on the synthesis of higher analogues (n = 2, 3)25,32–35 and all of them require 4–6 steps from commercially available starting materials. Our one-step route to these critical intermediates will greatly accelerate the discovery of new applications of amino(oligo)thiophene derivatives. Here the yields of Cu-catalyzed amination reaction, except for a dimethyl amine case, are still low due to a competing debromination process. Development of more selective amination catalysts is highly desirable.

A bridged version, 4, has also been prepared for comparison (see Scheme 2). Bridged bithiophene 8 was prepared from 3-bromothiophene according to literature methods.36–39 Subsequent methylation, formylation, and bromination afforded the properly functionalized 11 that can be used following the general route in Scheme 1.

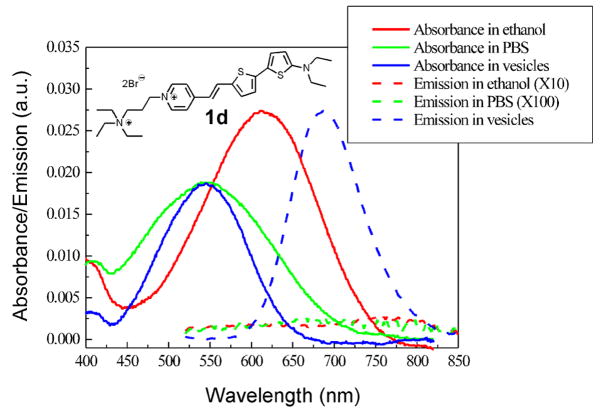

SCHEME 2.

Synthesis of a bridged hemicyanine

Absorption and fluorescence properties

A. General properties and effect of solvent environment

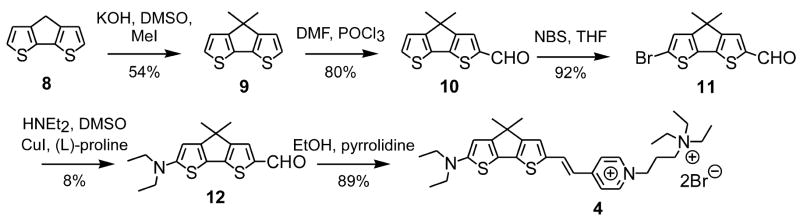

Hemicyanines containing aniline donor moieties,20 instead of amino-thiophene, have absorbance maxima in a range of 485–510 nm. The new amino(oligo)thiophene-based hemicyanines have absorbance maxima in ethanol in the 600 nm region and their solutions in ethanol are blue or green. As a typical example, absorption and emission spectra of 1d are shown in Figure 1. The absorption spectra in lipid vesicles and PBS buffer are blue-shifted by about 70 nm from that in ethanol; this can be explained by solvent stabilization of the positive charge in the ground state, but less effective solvation in the vertically excited states due to the migration of positive charge to the amino end of the chromophore.17 The fluorescence quantum yield of 1d is 0.10 when bound to lipid vesicles, but it is less than 0.001 in ethanol and PBS buffer. Such dramatic enhancement of fluorescence upon binding has long been known for traditional hemicyanine dyes and may be attributed to the shielding of excited states from polar-molecule-induced nonradiative pathways20 and slowing down of torsional relaxation pathways.40 This unique feature of hemicyanine dyes offers advantage of low background signals even in situations where the removal of excess dyes is too challenging, e.g. intracellular membrane studies. Furthermore, for most of the dyes, there is a large Stokes shift (Δλ ≈ 140 nm for 1d) that allows convenient filtering of the excitation and emission in fluorescence microscopic studies.

FIGURE 1.

Absorption and emission spectra of 1d in different solvent environments. The emission curves in ethanol and PBS buffer have been scaled 10 and 100 times respectively. Here lipid vesicles prepared from soybean phosphatidylcholine are used to represent the environment of cell membranes. Excitation wavelength: 480 nm.

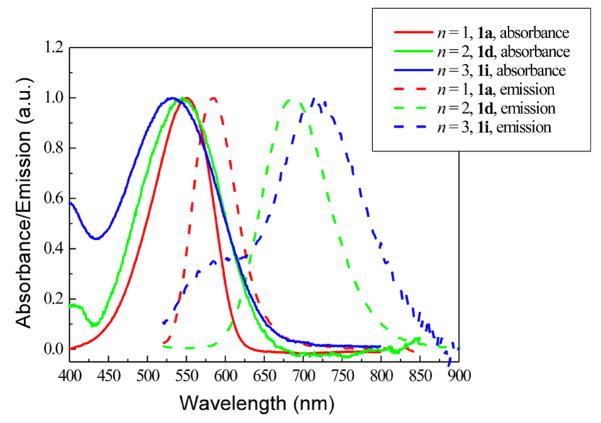

B. Effect of conjugation length

We assessed how the absorption and emission spectra changed as a function of the number of thienylene units. For comparison, the absorption and emission spectra, measured in vesicle suspensions, of dye 1a (n = 1), 1d (n = 2), and 1i (n = 3) are shown together in Figure 2. Although it is known that vinylene extension does not induce large bathchromic shift in absorption of hemicyanines,20 it is still surprising to find that thienylene extension actually produces small hypsochromic shift when the dyes are bound to lipid membranes (see Figure 2). However, when measured in ethanol the absorption peaks of 1d (λmax = 614 nm) and 1i (λmax = 588 nm) are indeed red-shifted relative to 1a (λmax = 569 nm) (Table 1). This trend can be understood by the larger charge separation in the vertical excited state of the more conjugated members of this family, causing them to display greater solvatochromism. On the other hand, when their fluorescence properties are compared, the longer the conjugation length, the longer the emission wavelength even for the lipid vesicle-bound dyes (see Figure 2 and Table 1). The fluorescence quantum yields of 1a and 1d are around 10%, but that of 1i is only 2%, discouraging further work on higher homologues. This low fluorescence quantum yield is most likely caused by torsional relaxation by rotation around intervening single bonds,40 which are most abundant in 1i.

FIGURE 2.

Normalized absorption and emission spectra of a series of dyes with different number of thienylene units, measured in vesicle suspensions containing 1 mg/mL soybean phosphatidylcholine in PBS buffer.

TABLE 1.

Spectroscopic properties of amino(oligo)thiophene-based hemicyanines

| Compound | ; logε | ; FQY | Fluorescence sensitivity to membrane potentiale ΔF/F per 100 mV Ex/Em (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

1a

|

569; 4.8a | 606; 0.003a | 1.5% 530/>590 |

| 559; 4.7b | 612; 0.001b | ||

| 551; 4.6c | 586; 0.07c | ||

1b

|

571; 4.7a | 610; 0.005a | 1.5% 555/>610 |

| 564; 4.6b | 614; 0.002b | ||

| 536; 4.5c | 588; 0.10c | ||

1c

|

594; 4.4a | −d | 8.0% 640/>715 |

| 529; 4.3b | −d | ||

| 530; 4.3c | 676; 0.10c | ||

|

1d |

614; 4.3a | −d | 5.0% 625/>715 |

| 539; 4.1b | −d | ||

| 547; 4.2c | 686; 0.10c | ||

|

1e |

616; 4.3a | −d | 18% 640/>715 |

| 567; 4.2b | −d | ||

| 547; 4.2c | 692; 0.10c | ||

|

1f |

621; 4.4a | −d | 10% 635/>715 |

| 567; 4.1b | −d | ||

| 554; 4.2c | 694; 0.11c | ||

|

1g |

617; 4.3a | −d | 11% 640/>715 |

| 544; 4.1b | −d | ||

| 547; 4.2c | 690; 0.12c | ||

1h

|

612; 4.4a | −d | 7.9% 640/>715 |

| 545; 4.3b | −d | ||

| 556; 4.3c | 688; 0.10c | ||

|

1i |

588; 4.3a | −d | 4.2% 640/>715 |

| 508; 4.1b | −d | ||

| 535; 4.2c | 714; 0.020c | ||

2

|

734; 4.3a | −d | 3.9% 690/>780 |

| 640; 4.0b | −d | ||

| 620; 4.2c | 758; 0.015c | ||

|

3 |

830; 4.5a | −d | −f |

| 704; 4.3b | −d | ||

| 704; 4.2c | −d | ||

|

4 |

707; 4.7a | −d | 2.5% 655/>715 |

| 552; 4.5b | −d | ||

| 618; 4.4c | 704; 0.016c |

Ethanol.

PBS buffer.

Lipid vesicles.

FQY < 0.001.

Fluorescence changes for a 100mV step in membrane potential were measured with excitation through a monochromator (20 nm bandwidth) and emission through a long pass filter at the indicated wavelengths.

Sensitivity cannot be measured due to low fluorescence.

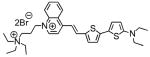

C. Effect of acceptor

Using a larger heterocyclic acceptor has proven effective in red-shifting the optical spectra of a hemicyanine dye.4 Shown in Figure 3 are the absorption and emission spectra of a series of dyes with different acceptors: pyridinium for 1d, quinolinium for 2, and acridinium for 3. For each additional fused benzo ring, there is ~75 nm red-shift in both absorption and emission spectra, but there is also a successive drop in fluorescence quantum yield, with acridinium salt 3 being not fluorescent at all. The mechanism might be due to steric hindrance induced by the fused benzo rings, which effectively prevents the chromophore from attaining a fluorescent planar conformation.

FIGURE 3.

Normalized absorption and emission spectra of a series of dyes with different acceptors, measured in vesicle suspensions containing 1 mg/mL soybean phosphatidylcholine in PBS buffer.

D. Effect of rigidification

Incorporating methine groups in a ring has been very successful in red-shifting the absorption peaks and improving the photostabilities of polymethine dyes.41 To test the effect of rigidification in our amino(oligo)thiophene-based dyes we synthesized a CMe2-bridged dye, 4 (see Scheme 2). Compared with the non-bridged 1d, 4 shows a large red-shift (Δλ = 65 nm) in the absorption spectrum and a small red-shift (Δλ = 18 nm) in the fluorescence spectrum, both of which were measured in vesicle suspensions.

E. Effect of side chains

Two series of dyes with varying alkyl substitutes, R1 on the hydrophobic side and R2 on the hydrophilic side, have been synthesized. The R1 series (1c–1f, see Table 1) show progressive red-shifts in both absorption and emission spectra when the alkyl chain increases from methyl to n-butyl. This trend may be understood in terms of the HOMO-LUMO gap: for hemicyanines the HOMO resides mostly on the amine side and the LUMO on the pyridinium side.15 The larger the size of the alkyl chain the more the amino nitrogen is shielded from hydrogen bonded solvation, destabilizing the ground state relative to the excited state and thus red shifts the absorption and emission maxima. It is not surprising that only minimal variations in absorption and emission spectra are observed for R2 series (1d, 1g, and 1h, see Table 1) since these alkyl chains are quite remote from the chromophore. Although the effects on spectra are not substantial, side chains do play critical roles in optimizing solubility, membrane binding kinetics and avidity, and even voltage sensitivities (vide infra).

Applicability assessment A: sensitivity to transmembrane potential

Historically hemicyanines are best known for their voltage sensitivities. A typical hemicyanine dye has a hydrophobic tail and a hydrophilic head that promote binding and alignment within cell membranes. Since optical excitation of a hemicyanine dye involves charge redistribution, the transmembrane potential has a measurable effect on the excitation energy, and indeed voltage sensitivities can be conveniently measured using a hemispherical lipid bilayer apparatus.18 The voltage sensitivities of these dyes, expressed in fluorescence change per 100 mV, are included in Table 1. A few points are clear from a glance at the table: first, the average sensitivity of monothiophene series (1a–b), 1.5%, is much lower than that of bithiophene series (1c–h), 10%; secondly, the side chains have significant effects on the sensitivity, i.e. 1d and 1e differ only in side chains but have very different sensitivities. Extensive optimization of side chains results in 1e with a sensitivity of 18%, which is among the highest reported for fast voltage sensitive dyes.26,42 On the other hand no attempts have been made to optimize other series (1i, 2, 3, and 4) due to their relatively low fluorescence quantum yields, (≤2%).

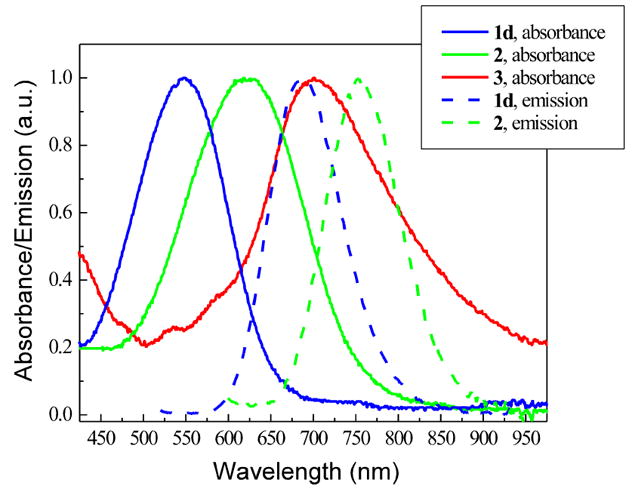

Applicability assessment B: sensitivity to lipid compositions

Even in the absence of proteins, the cell membrane is a highly heterogeneous 2-dimensional liquid phase. “Rafts”, domains enriched in cholesterol and saturated lipids, floating in a fluidic lipid bilayer have been proposed as a feature of cell membrane structure.43 Rafts play important roles in cellular functions such as signal transduction and membrane trafficking.44 Fluorescence imaging of domains in model biomembranes can be realized using two dyes having complementary staining preferences45 or one dye with domain-sensitive fluorescence characteristics (polarization, wavelength, lifetime, etc.).21,46–49 The large Stoke shifts and solvatochromic effects of these new hemicyanines prompted us to assess the sensitivity to membrane composition. Model membranes for liquid disordered phase and liquid ordered phase were prepared from 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), and 7:3 1,2-dipalmitoylsn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC)/cholesterol respectively. Figure 4 shows the emission spectra of two representative hemicyanines, 1b and 1d, in two types of vesicle suspensions. 1d shows increased and blue-shifted (30 nm) fluorescence in 7:3 DPPC/cholesterol vesicles relative to DOPC vesicles; in contrast, 1b shows decreased and red-shifted (20 nm) fluorescence in 7:3 DPPC/cholesterol vesicles. All monothiophene and bithiophene derivatives tested show similarly contrasting lipid composition dependent emission spectra. Although we cannot provide a detailed explanation for the sensitivity of these dyes to membrane environment, it is important to note that only the emission spectra are sensitive, not the absorption spectra. Therefore, any explanation would have to involve the detailed interactions of the relaxed excited state structure with its lipid environment. These lipid compositions do produce very different intramembrane electric potential; in particular, cholesterol imparts a very strong dipole electric field at the membrane surface.50,51 Furthermore, cholesterol is known to produce a liquid ordered phase that is more rigid than the liquid disordered phase associated with DOPC.43 The relatively large shifts of fluorescence peak, together with long emission wavelengths, make them very promising probes for the detection of lipid variation in cell membranes.

FIGURE 4.

Emission spectra of 1b and 1d in vesicle suspensions prepared from DOPC or 7:3 DPPC/cholesterol in PBS buffer. Lipid concentration = 0.017 mg/mL.

Applicability assessment C: nonlinear optical imaging

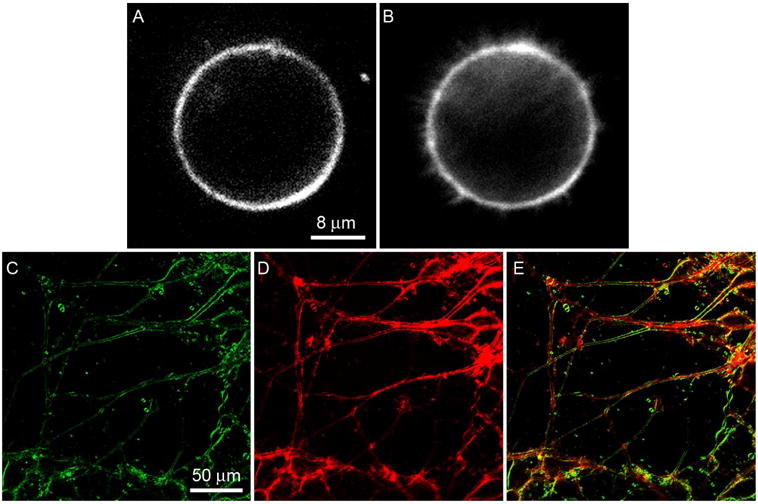

Two-photon fluorescence (2PF)52–55 and second harmonic generation (SHG)56,57 are two useful nonlinear optical phenomena for biomedical imaging. Since such phenomena occur only at the diffraction-limited focal point, nonlinear optical microscopy has intrinsic 3D sectioning capability and minimal out-of-focus photo-bleaching. Furthermore, in nonlinear microscopy, near-IR lasers can be used even for fluorophores that are traditionally used with UV/Vis sources. Recent advances in diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) lasers have made near-IR lasers extremely compact and affordable, with green laser pointer (532 nm) as the most common product utilizing DPPS laser (1064 nm) through an SHG process. To our delight, most of the dyes (1a–1i) have a significant absorbance at 532 nm, making them perfect for 2PF and SHG excited with mode locked 1064 nm lasers. Although the SHG process does not involve absorption of photons, it is resonance-enhanced when the frequency-doubled light is close to the absorption peak. The bithiophene series (1c–1h) shows strong nonlinear optical properties and high quality 2PF and SHG images are readily obtained. Figure 5A and 5B show SHG and 2PF images of the same neuroblastoma cell before differentiation. Filopodia, filamentous structures emanating from the round cell, can be seen clearly in the 2PF image, but are absent in the SHG image. This is because SHG requires a non-centrosymmetric distribution of harmonophores on the scale of the optical coherence length, and thus is unable to image highly symmetric or tiny structures like filopodia. The images of differentiated neuroblastoma cells, Figure 5C and 5D, illustrate another interesting phenomenon: internal membranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum are not imaged in SHG (5C) even when the dye has apparently been internalized to an extent that the 2PF contrast pattern is dominated by interior fluorescence (5D). This is particularly apparent in the color overlay image of Figure 5E, where many of the neurites display red interiors from the 2PF channel and green peripheries from the SHG channel. This is because the highly convoluted fine structure of the endoplasmic reticulum has the effect of randomly orienting the dye molecules on the spatial scale of the optical coherence length. The use of chiral dyes has been shown to relax the requirement of structural asymmetry.57

FIGURE 5.

(A) SHG, (B) 2PF images of the same undifferentiated neuroblastoma cell; (C) SHG, (D) 2PF, and (E) merged images of differentiated neuroblastoma cells. The samples were stained with 5 μM 1d and excited at 1064 nm. A bandpass filter (615–665 nm) was used in 2PF imaging. SHG was collected in the transmitted light path at 532 nm.

On the other hand, the monothiophene dyes (1a–1b) generally show signals that are more than an order of magnitude lower. An example of weak 2PF and SHG images of neuroblastoma cells stained with 1b is provided in Figure S1 in the supporting information; these images were obtained with the same settings on our non-linear microscopy apparatus as the images in Figure 5. The inferior nonlinear optical properties of the monothiophene series may be attributed to their different donor-acceptor distances.

Conclusions

A series of hemicyanines based on amino(oligo)thiophene donors have been developed. Owing to thiophene’s balanced stability and wavelength-shifting ability, these hemicyanines show fluorescence in the red and near infrared region but are still compact and readily synthesized. Every element of a hemicyanine structure—donor, acceptor, bridge, and even side chains—has been varied to study the structure-property relationship and to identify the most promising probes. Some of these dyes have shown superior sensitivities to trans-membrane potentials and membrane lipid compositions. In addition they have demonstrated strong nonlinear optical properties and, due to their absorption peaks around 532 nm, inexpensive and compact diode-pumped solid-state fiber laser (1064 nm) can be employed in two photon fluorescence and second harmonic generation imaging. The relatively compact structure, facile synthesis, high environment sensitivity, long wavelength fluorescence, and strong nonlinear optical properties make them promising probes for a wide range of biological applications.

Experimental Procedures

General

4H-cyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b′]dithiophene (8) was synthesized according to the literature methods.36–39

5-Diethylamino-thiophene-2-carboxaldehyde (6a)

5-Bromothiophene-2-carboxaldehyde (380 mg, 2.0 mmol), diethylamine (440 mg, 6.0 mmol), and 10 mL H2O were stirred at 100 °C in a pressure vessel for 41 h. After cooling down, the organic compounds were separated by extraction with CH2Cl2, and purified by column chromatography (SiO2, solvent gradient: CH2Cl2 to 1:1 CH2Cl2/EtOAc) to furnish 192 mg product (52%). Rf (silica gel, 1:1 CH2Cl2/EtOAc) = 0.63; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ1.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6 H), 3.42 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4 H), 5.92 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.46 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 9.48 (s, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.1, 47.6, 102.7, 125.3, 140.8, 166.4, 179.6; MS (EI): m/z = 183 [M]+.

5′-Dimethylamino-2,2′-bithiophene-5-carboxaldehyde (6c)

5′-Bromo-2,2′-bithiophene-5carboxaldehyde (100 mg, 0.37 mmol), dimethylamine (40% solution in H2O, 1 g, 8.9 mmol), CuI (13.9 mg, 0.073 mmol), Cu (4.7 mg, 0.074 mmol), K3PO4·H2O (155.4 mg, 0.73 mmol) and 1 mL N,N-dimethylethanolamine were stirred at 80 °C in a pressure vessel for 87 h. Solution turned red during the reaction. After cooling down, the reaction mixture was filtered through a short column of silica gel and eluted with more EtOAc. The eluent was concentrated under vacuum and was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, CH2l2) to furnish 74.8 mg red solid (86%). The product shows strong green fluorescence when dissolved in CH2C12. R/(silica gel, CH2C12) = 0.36; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDC13): δ 3.00 (s, 6 H), 5.81 (d, J= 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.95 (d, J= 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.13 (d, J= 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.57 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 9.75 (s, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDC13): δ 42.6, 102.9, 119.5, 120.7, 127.8, 138.2, 138.6, 149.8, 161.3, 182.0; MS (EI): m/z = 237 [M]+.

1-(3-Triethylammoniopropyl)-4-methylpyridinium dibromide (7b)

4-Methylpyridine (307 mg, 3.3 mmol), (3-bromopropyl)triethylammonium bromide (1.0 g, 3.3 mmol), and 4 mL DMF were stirred at 100 °C in a pressure vessel for 41 h. Precipitates formed during the reaction. After cooling down, the precipitates were filtered out and washed with CH2Cl2 to give 7b as a light pink solid (750 mg, 57%), which was used in the next aldol condensation without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 1.34 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 9 H), 2.50 (m, 2 H), 2.70 (s, 3 H), 3.35–3.47 (m, 8 H), 4.73 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.99 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2 H), 8.98 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 8.0, 22.1, 25.2, 54.4, 54.5, 58.3, 130.1, 145.2, 161.9; HRMS (FAB+): m/z = 315.1428 [M-Br]+ (calcd for C15H28BrN2: 315.1430).

Hemicyanine 1a

5-Diethylamino-thiophene-2-carboxaldehyde (18 mg, 0.10 mmol), 1-(3-triethylammoniopropyl)-4-methylpyridinium dibromide (40 mg, 0.1 mmol), 0.1 mL pyrrolidine, and 5 mL ethanol were stirred at 100 °C in a pressure vessel for 16 h. The solution turned red during the reaction. After cooling down, the solvent was evaporated under vacuum and the residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2-amino, 2:98 MeOH/CH2Cl2 to elute impurities; 1:4 MeOH/CH2Cl2 to elute a purple product) to give 1a as a purple solid (47.0 mg, 84%). Rf (silica gel, 24:4:16:6:6 CHCl3/i-PrOH/MeOH/H2O/AcOH) = 0.30; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 1.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6 H), 1.33 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9 H), 2.40 (m, 2 H), 3.34–3.43 (m, 8 H), 3.52 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4 H), 4.44 (t, 2 H), 6.11 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.36 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.33 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.70 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 7.98 (d, J =15.0 Hz, 1 H), 8.43 (br, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.9, 12.6, 24.9, 54.4, 54.5, 56.5, 105.5, 112.6, 121.8, 124.9, 138.4, 140.7, 143.3, 156.1, 165.6; HRMS (FAB+): m/z = 480.2054 [M-Br]+ (calcd for C24H39BrN3S: 480.2048).

Imaging System

For full details of our non-linear imaging microscope, we refer the reader to previously published descriptions.58 Our microscope combines a Fluoview (Olympus) scan-head and an Axiovert (Zeiss) inverted microscope. For excitation we use a Femtopower (Fianium) fiber laser operating at 1064 nm and an IR-Achroplan (Zeiss) 40×, 0.8 NA water-immersion objective. 2PF is collected back through the objective, passed through a 50-nm wide band-pass filter centered at 640 nm (Chroma) and detected by a Hamamatsu R3896 photo-multiplier tube with an original Fluoview I-to-V converter. SHG is collected in the forward direction by a 0.55 NA (Zeiss) condenser, filtered through a 20-nm wide band-pass filter centered at 532 nm (Newport) and detected by a Hamamatsu H7421-40 photon-counting head.

Lipid Vesicle Preparations

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-dipalmitoylsn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), and cholesterol were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids; soybean phosphatidylcholine was obtained from Sigma Chemical Company. At first lipids were dissolved in chloroform, and then the solvent was removed using an argon stream to yield a lipid film. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was added to hydrate the film and the mixture was sonicated to clarity with a Branson W-185 probe-type sonicator.

Cell Preparations and Staining Protocol

N1E-115 mouse neuroblastoma cells were cultured using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic and maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Dye solutions (1–10 μM) were prepared by diluting stock solutions in ethanol with Earle’s balanced salt solution, followed by vigorous sonication. After removing the culture medium from a dish of cells, 3 mL of dye solution was added and the cells were imaged at excitation wavelength of 1064 nm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health via grant Nos. EB001963 and U54RR022232.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Synthesis and characterization of 6b, 6d, 6e, 6f, 6g, 7a, 7c, 7d, 7e, 9, 10, 11, 12, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e, 1f, 1g, 1h, 1i, 2, 3, 4; SHG and 2PF images of neuroblastoma cells using 1b as the staining reagents; 1H NMR spectra of all new compounds; 13C NMR spectra of representative intermediates and products (6a, 6c, 7b, 1a, 1c, 1d). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Giepmans BNG, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. Science. 2006;312:217. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissleder R. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;79:316. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frangioni JV. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wuskell JP, Boudreau D, Wei MD, Jin L, Engl R, Chebolu R, Bullen A, Hoffacker KD, Kerimo J, Cohen LB, Zochowski MR, Loew LM. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;151:200. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mujumdar SR, Mujumdar RB, Grant CM, Waggoner AS. Bioconjug Chem. 1996;7:356. doi: 10.1021/bc960021b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki E, Kojima H, Nishimatsu H, Urano Y, Kikuchi K, Hirata Y, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3684. doi: 10.1021/ja042967z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umezawa K, Nakamura Y, Makino H, Citterio D, Suzuki K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1550. doi: 10.1021/ja077756j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matz MV, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov SA. BioEssays. 2002;24:953. doi: 10.1002/bies.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Campbell RE, Ting AY, Tsien RY. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:906. doi: 10.1038/nrm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim YT, Kim S, Nakayama A, Stott NE, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Mol Imaging. 2003;2:50. doi: 10.1162/15353500200302163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raschke G, Brogl S, Susha AS, Rogach AL, Klar TA, Feldmann J, Fieres B, Petkov N, Bein T, Nichtl A, Kurzinger K. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1853. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halim M, Tremblay MS, Jockusch S, Turro NJ, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7704. doi: 10.1021/ja071311d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Badger PD, Geib SJ, Petoud S. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:2508. doi: 10.1002/anie.200463081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn H. J Chem Phys. 1949;17:1198. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loew LM, Bonneville GW, Surow J Biochemistry. 1978;17:4065. doi: 10.1021/bi00612a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loew LM, Scully S, Simpson L, Waggoner AS. Nature. 1979;281:497. doi: 10.1038/281497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loew LM, Simpson L, Hassner A, Alexanian A. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:5439. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loew LM, Simpson LL. Biophys J. 1981;34:353. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassner A, Birnbaum D, Loew LM. J Org Chem. 1984;49:2546. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fluhler E, Burnham VG, Loew LM. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5749. doi: 10.1021/bi00342a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin L, Millard AC, Wuskell JP, Dong XM, Wu DQ, Clark HA, Loew LM. Biophys J. 2006;90:2563. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang YA, Lewis A, Loew LM. Biophys J. 1988;53:665. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marder SR, Cheng LT, Tiemann BG, Friedli AC, Blancharddesce M, Perry JW, Skindhoj J. Science. 1994;263:511. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5146.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roncali J Chem Rev. 1997;97:173. doi: 10.1021/cr950257t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Effenberger F, Würthner F, Steybe F. J Org Chem. 1995;60:2082. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salama G, Choi BR, Azour G, Lavasani M, Tumbev V, Salzberg BM, Patrick MJ, Ernst LA, Waggoner AS. J Membr Biol. 2005;208:125. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prim D, Kirsch G, Nicoud JF. Synlett. 1998:383. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Z, Twieg RJ. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:903. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Cai Q, Ma DW. J Org Chem. 2005;70:5164. doi: 10.1021/jo0504464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breitung EM, Shu CF, McMahon RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1154. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Würthner F, Yao S, Schilling J, Wortmann R, Redi-Abshiro M, Mecher E, Callego-Gomez F, Meerholz K. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2810. doi: 10.1021/ja002321g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raposo MMM, Fonseca AMC, Kirsch G. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:4071. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raposo MMM, Kirsch G. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:4891. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikemoto N, Estevez I, Nakanishi K, Berova N. Heterocycles. 1997;46:489. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedworth PVYC, Jen A, Marder SR. J Org Chem. 1996;61:2242. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraak A, Wiersema AK, Jordens P, Wynberg H. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:3381. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beyer R, Kalaji M, Kingscote-Burton G, Murphy PJ, Pereira V, Taylor DM, Williams GO. Synth Met. 1998;92:25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nenajdenko VG, Baraznenok IL, Balenkova ES. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6132. doi: 10.1021/jo980079e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amer A, Burkhardt A, Nkansah A, Shabana R, Galal A, Mark HB, Zimmer H. Phosphorus, Sulfur, Silicon. 1989;42:63. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva GL, Ediz V, Yaron D, Armitage BA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5710. doi: 10.1021/ja070025z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds GA, Drexhage KH. J Org Chem. 1976;42:885. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhn B, Fromherz P. J Phys Chem. 2003;107:7903. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simons K, Ikonen E. Nature. 1997;387:569. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simons K, Toomre D. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:31. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumgart T, Hess ST, Webb WW. Nature. 2003;425:821. doi: 10.1038/nature02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parasassi T, Gratton E, Yu WM, Wilson P, Levi M. Biophys J. 1997;72:2413. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78887-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owen DM, Lanigan PMP, Dunsby C, Munro I, Grant D, Neil MAA, French PMW, Magee AI. Biophys J. 2006;90:L80. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Margineanu A, Hotta JI, Van der Auweraer M, Ameloot M, Stefan A, Beljonne D, Engelborghs Y, Herrmann A, Muellen K, De Schryver FC, Hofkens J. Biophys J. 2007;93:2877. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HM, Jeong BH, Hyon JY, An MJ, Seo MS, Hong JH, Lee KJ, Kim CH, Joo T, Hong SC, Cho BR. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4246. doi: 10.1021/ja711391f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starke-Peterkovic T, Turner N, Vitha MF, Waller MP, Hibbs DE, Clarke RJ. Biophys J. 2006;90:4060. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latorre R, Hall JE. Nature. 1976;264:361. doi: 10.1038/264361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW. Science. 1990;248:73. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HM, Jung C, Kim BR, Jung SY, Hong JH, Ko YG, Lee KJ, Cho BR. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:3460. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim HM, Kim BR, Hong JH, Park JS, Lee KJ, Cho BR. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:7445. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HM, An MJ, Hong JH, Jeong BH, Kwon O, Hyon JY, Hong SC, Lee KJ, Cho BR. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:2231. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campagnola PJ, Loew LM. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1356. doi: 10.1038/nbt894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan P, Millard AC, Wei M, Loew LM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11030. doi: 10.1021/ja0635534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millard AC, Jin L, Wei M, Wuskell JP, Lewis A, Loew LM. Biophys J. 2004;86:1169. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74191-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.