Abstract

The rhythm of plasma melatonin concentration is currently the most accurate marker of the endogenous human circadian pacemaker. A number of methods exist to estimate circadian phase and amplitude from the observed melatonin rhythm. However, almost all of these methods are limited because they depend on the shape and amplitude of the melatonin pulse, which varies among individuals and can be affected by environmental influences, especially light. Furthermore, these methods are not based on the underlying known physiology of melatonin secretion and clearance, and therefore cannot accurately quantify changes in secretion and clearance observed under different experimental conditions. A published physiologically-based mathematical model of plasma melatonin can estimate synthesis onset and offset of melatonin under dim light conditions. We amended this model to include the known effect of melatonin suppression by ocular light exposure and to include a new compartment to model salivary melatonin concentration, which is widely used in clinical settings to determine circadian phase. This updated model has been incorporated into an existing mathematical model of the human circadian pacemaker and can be used to simulate experimental protocols under a number of conditions.

Keywords: Circadian Rhythm; drug effects; physiology; Computer Simulation; Humans; Light; Melatonin; pharmacokinetics; pharmacology; Models, Biological; Saliva; drug effects

Keywords: melatonin , mathematical models , sleep , circadian , suppression , plasma, saliva, ocular

Introduction

The activity of the endogenous circadian pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) within the hypothalamus cannot be measured directly in humans. In order to extract information about circadian phase or amplitude or other characteristics of the circadian system, overt marker rhythms must be used. A comparison of the plasma melatonin rhythm to two other marker rhythms, core body temperature and cortisol, revealed that phase markers measured by melatonin were the least variable under relatively constant conditions, and therefore are more precise markers of the endogenous circadian rhythm (1). Melatonin is also commonly used as a marker in circadian rhythms research because it can be assayed in blood, saliva or urine and because it is relatively unaffected by sleep-wake state or changes in posture (2).

Multiple mathematical methods have been published (for review, see (2) and (1)) by which circadian phase can be extracted from the plasma melatonin rhythm. Most of these methods depend on curve-fitting of the melatonin profile and/or the crossing of a threshold to determine phase. Thus, these methods assume certain characteristics about the shape and amplitude of the melatonin profile. For example, to calculate phase as the “quarter crossing of the fit” (DLMO25%), the amplitude of a melatonin pulse is calculated from a 3-harmonic fit of the data, which assumes that the shape of the melatonin pulse can be captured by a fundamental plus 2-harmonic (e.g., approximately 24, 12, and 8 hr) sinusoidal curve. Then, 25% of this fit amplitude is calculated and linear interpolation is used to estimate the time at which the plasma melatonin concentration crosses this value. This time is used as the phase marker (see Fig. 3 Fig. 3 of (3)).

Fig. 3.

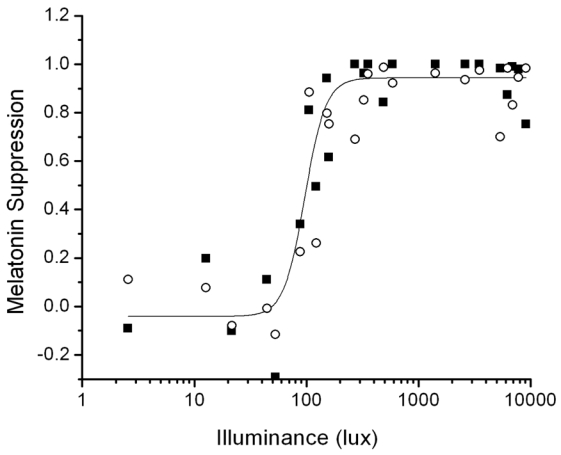

Predictions of the 1 Pulse Intensity Response Curve protocol (filled squares) fit by a 4-parameter logistic function (solid line) compared to the experimental data (open circles).

This or similar phase estimates may not be accurate for several reasons: a) There is large intra-individual variability in melatonin amplitude and shape across several days, especially during an experimental intervention such as a light pulse under different background lighting conditions (4); b) There is large inter-individual variability in melatonin amplitude (5), (6). Therefore, some threshold methods may not be accurate in individuals with low amplitude of melatonin concentration; c) Linear interpolation assumes that the change in melatonin concentration across the interpolation interval is linear, which may not be true, especially when sampling rate is infrequent.

There are two other problems with most current measures of melatonin phase and amplitude. Most investigators agree that the increase of melatonin secretion is a marker of circadian phase [need reference]. However, the different definitions of this increase – which depend on the threshold or fit used – make it difficult to compare results across studies, or even to associate the time of the change with the physiology. A second problem is that the error in the calculation is not reported. Some circadian rhythms experiments report phase shifts of as little as 30 minutes as significant. However, without knowledge of the error in the phase marker, the statistical significance of the results and the statistical power of the experiments may not be known.

The suppression of melatonin by ocular light exposure has been used to probe the sensitivity of the circadian pacemaker to light in blind persons (7), to varying intensities and durations of polychromatic light exposure, and to long-term changes in light exposure (4). This method is appropriate because the pathway for ocular light suppression of melatonin begins in the retina, travels via the single-synaptic retino-hypothalamic tract (RHT) to the SCN of the hypothalamus, through the paraventricular nuclei (PVN) and the superior cervical ganglion (SCG) and ends in the pineal (8). Intensity response curves (9) demonstrate that the half-maximum sensitivity to light estimated from plasma melatonin suppression occurs at approximately 100 lux, with maximum melatonin suppression occurring between 1000 and 10000 lux. For comparison, ordinary room light levels are approximately 100 lux; studies conducted in room light may inadvertently include melatonin suppression in addition to other specified experimental effects. More recent studies have also reported melatonin suppression by monochromatic light with peak sensitivity in the short-wavelength bands (10) (11) (12) (13).

In 1997, Brown et al. (14) introduced a method for calculating melatonin phase and amplitude using a physiologically-based differential equation model of the diurnal variation of plasma melatonin concentrations. Details of the model are included below, in the Methods section. This model can be used to estimate the onset (SynOn) and offset (SynOff) of plasma melatonin production, as well as the amount of melatonin secreted (amplitude). The onsets and offsets estimated by the model were comparable to assessments of melatonin phase based on threshold methods. This method also yields information about the infusion rates of melatonin into and clearance rates of melatonin out of the plasma, information that cannot be extracted using the other methods but that may be useful in understanding the physiology. A method to estimate melatonin phase that is based on physiology may be a much more useful tool for melatonin analysis because there are no intrinsic assumptions about the shape and amplitude of the melatonin pulse and because the parameters (e.g., synthesis onset and offset, infusion and clearance rates, amplitude) can be directly related to secretory processes. Such information may provide physiological insight into the differences in melatonin levels seen across individuals, and in different conditions.

Salivary melatonin rhythms have also been used as markers of the endogenous circadian pacemaker. Saliva samples for melatonin assay are often collected when it is impossible or impractical to collect plasma samples. Phase estimates are usually calculated by the same curve-fitting and threshold methods used for plasma melatonin. However, in addition to the problems detailed above for analyzing plasma samples for circadian information, there are at least two additional problems with using saliva for this purpose: (a) Salivary melatonin concentrations are ~30% lower than plasma melatonin concentrations (15) which may make threshold methods even more difficult to apply and (b) often only the rising portion of the salivary melatonin pulse is collected, because most melatonin secretion occurs when an individual is asleep and therefore not available for producing saliva samples. The lack of data from the entire time of melatonin secretion makes it impossible to use any threshold calculation that depends on the overall amplitude of the pulse.

We developed two additions to the existing physiologically-based model of melatonin: (a) a photic effect to predict melatonin suppression by light and (b) a saliva compartment to predict salivary melatonin concentration. This model was then integrated with an existing mathematical model of the effect of light on the human circadian pacemaker (16) and used to estimate melatonin synthesis onset and offset, amplitude and infusion and clearance rates from data collected under a variety of conditions, including (a) a constant routine procedure (CR, described below); (b) exposures to continuous bright light, continuous dim light and intermittent bright light; and (c) conditions in which melatonin sampling rate was low or only included the rising portion of the melatonin curve. We compare these predictions to other known methods of melatonin phase estimation and discuss which methods are most accurate under a variety of experimental conditions.

Methods

Model Equations

The physiologically-based model of melatonin developed by Brown and colleagues (14) was based on the physiological data of melatonin synthesis, secretion and clearance from rats; it is assumed that the same or similar physiology exists for humans. The pathway for pineal melatonin synthesis includes the following steps: tryptophan is hydroxylated and then decarboxylated to form serotonin. Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT) converts serotonin to N-acetylserotonin (17), which is then O-methylated by hydroxindole-O-methyltransferase to produce melatonin (18). Melatonin is not stored in the pineal, which is on the body side of the blood brain barrier, and readily diffuses into the bloodstream (19), where it is transported through the blood, partially bound to albumin (20). The hormone is cleared by the liver and excreted through the urine (21). The mathematical model of this synthesis is a first-order kinetic process with two compartments: the pineal compartment and the plasma compartment. These two compartments are represented by two first-order differential equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where βI is the rate of infusion of melatonin into the plasma, βC is the rate of clearance of melatonin from the plasma, H1(t) is the concentration of melatonin in the pineal compartment and H2(t) is the concentration of melatonin in the plasma. A(t) is the AANAT activity at time t and is calculated by the following function:

| (3) |

where λ is the AANAT activity growth, α is the AANAT activity decline, ton is the onset time of increased AANAT activity and toff is the offset time of growth in AANAT activity and A is the maximum AANAT activity (pmol·l−1·min1). Although the original model was based on the assumption that AANAT activity is the rate limiting step of melatonin synthesis, more recent studies indicate that this may not be the case [Liu and Borjigin 2005 J. Pineal Research – need to add to refman].

Data Analysis

Several datasets were used to develop and test the additions to the physiologically-based model of melatonin. Fluorescent white light was used in all studies (see (22) for details, including light spectrum). For all protocols, circadian phase was assessed during constant routines (CRs) using a 2-harmonic plus noise fit of Core Body Temperature (CBTmin) (23) and melatonin as phase markers. During a CR, individuals remain awake in bed under dim light with frequent small meals; the CR is designed to minimize changes known to affect markers of the circadian pacemaker (24)(25). CBTmin was used as the phase marker during the experiment to time events because CBT data are available in real time and can be analyzed immediately, unlike melatonin which must first be assayed. A description of each dataset follows:

Intermittent Bright Light (IBL) dataset

Gronfier et al. (3) performed a series of experiments to determine the response of the circadian pacemaker to a sequence of intermittent bright light pulses compared to the response of the pacemaker to a continuous bright light or very dim light pulse. In these experiments, 20 subjects were scheduled to two 24.0-hr days in ~90 lux followed by a 26.2-hr CR. After the initial CR, subjects were scheduled to 8 hr of sleep in 0 lux. For the next wake episode, subjects were randomly assigned to a 6.5-hr stimulus, centered ~3.5hr before CBTmin, in one of three lighting conditions: (1) continuous bright light (CBL) at ~9500 lux (n = 6); (2) intermittent bright light (IBL) consisting of six 15-minute bright light pulses of ~9500 lux separated by 60 minutes of very dim light of < 1 lux (n = 7); (3) continuous very dim light (VDL) of <1 lux (n = 7). In each condition, the stimulus was preceded and followed by 30 minutes of <1 lux. The stimulus day was followed by a 64-hr CR. The light level during wakefulness was ~1.5 lux from the start of the initial CR until the end of the second CR, except during the light exposure session. Although the IBL stimulus represented only 23% of the total duration of the continuous light exposure, the phase shift of DLMO25%, their marker of melatonin phase, during IBL exposure was 74% as great as during a CBL stimulus. Melatonin suppression was observed in the CBL and IBL conditions (26), but was not reported in (3). The data from this study were used to introduce the effect of light in the pineal melatonin concentration equation (Equation 1). The plasma melatonin concentrations from the light exposure days were used to develop and test the addition of a light suppression effect to the melatonin model. The plasma melatonin concentrations from the initial CR were used to determine the entrained phase angles between CBTmin and SynOn and SynOff.

3-Pulse Phase-Resetting Protocol

Duffy et al. (27) performed a series of experiments in which 31 subjects were scheduled to two 24.0-hr days in ~90 lux followed by a 26 to 33-hr CR, depending on the desired center of the bright light stimulus. After the initial CR, subjects were scheduled to 8 hr of sleep in 0 lux. During the following three wake episodes, subjects were exposed to a 5-hr ~9500 lux pulse centered in the middle of the 16-hr wake episode, which occurred at different circadian phases to either phase-advance or phase-delay the pacemaker. The 3-cycle bright light stimulus was followed by a 40-hr CR. CBT and plasma melatonin rhythms were assessed throughout the protocol. The light level during wakefulness was ~10 lux from the start of the initial CR until the end of the second CR, except during the bright light stimuli. The plasma melatonin concentrations from the initial CR were used to determine the entrained phase angles between CBTmin and SynOn and SynOff.

1-Pulse Intensity Response Curve Protocol

Zeitzer et al. (9) performed a series of experiments to determine the response of the pacemaker to light pulses of varying intensities. In these experiments, 21 subjects were scheduled to two 24.0-hr days in 150 lux followed by a ~50-hr CR. After the initial CR, subjects were scheduled to 8 hr of sleep in 0 lux. During the following wake episode, subjects were randomly assigned to receive a single 6.5-hr light pulse centered ~3.5 hr before CBTmin with intensities ranging from 3 lux to 9100 lux. The stimulus day was followed by a 30-hr CR. The light level during wakefulness was ~10 lux from the start of the initial CR until the end of the second CR, except during the stimulus. Melatonin suppression was calculated as the difference between the area under the curve (AUC) of the baseline melatonin pulse and the melatonin pulse during the light exposure divided by the baseline AUC. Baseline AUC was calculated from the 4-hr before the melatonin midpoint during the initial CR and the AUC during the light exposure was calculated using the same clock hours 24 hours later. AUC was calculated using the trapezoidal method. These data were used to validate the addition of a light suppression effect to the melatonin model.

Salivary Melatonin Concentration dataset

Both salivary and plasma samples were collected for melatonin assay from totally blind subjects scheduled to various inpatient protocols. The details of these protocols were described in Klerman et al. 1998 (28). Data from these totally blind subjects were not confounded by ocular light suppression of melatonin concentrations. The salivary melatonin data were used to test and validate the addition of a salivary compartment to the melatonin model.

Incorporation of an effect of light on melatonin

Previous Model

In 1999, Kronauer et al. (16) described a mathematical model of the effect of light on the human circadian pacemaker with a dynamic stimulus processor to represent the effect of light as a chemical reaction in which photons entering the retina activate “ready elements” (Process L) that are converted into a light drive that sends a signal to the circadian pacemaker in the SCN. Once the ready elements have been used, they are recycled back to a ready state to await reactivation. The dynamic stimulus processor assumes a prompt response occurring at the time the light source is turned on, with pseudosaturation occurring within 10–15 minutes before the drive returns to a lower steady state response until the light stimulus ends.

In this model, this light drive acts on the circadian pacemaker to produce phase shifts. The equations of Process L represent the physiological process by which light initiates a chemical reaction within the photo-pigments of the retinal photoreceptors that transmit a photic signal from the retina through the RHT to the circadian pacemaker within the SCN. This chemical reaction assumes a forward rate constant

| (4) |

where α0 = 0.05, I0 = 9500 and p = 0.5. Equation 4 converts ready elements into a drive B̂ onto the pacemaker such that

| (5) |

where G is a scaling constant and n is the fraction of elements in the system that are “used”. Used elements are recycled back into the ready state at a rate of β. In general, the rate at which elements are activated (processed from “ready” to “used”) in Process L is given at any time by the formula

| (6) |

The drive generated in Equation 5 acts onto the dynamic circadian pacemaker, Process P. Process P is divided into two components: the circadian pacemaker and the circadian sensitivity modulator. The coupled pacemaker equations are

| (7) |

| (8) |

Equations 7 and 8 represent a higher-order limit cycle oscillator, and the coefficients in Equation 7 were chosen so that the amplitude of the limit cycle would equal 1.00, as in previous iterations of the model (29).

B̂ enters Process P via the circadian sensitivity modulator, where it is converted into a direct drive, B, onto the pacemaker that is dependent on the state variables x and xc such that

| (9) |

to characterize the feature that the human circadian pacemaker has varying sensitivity to light throughout the circadian day (30).

To compare the results of the model to core body temperature (CBT) data in humans, a phase relationship was derived (31) such that

| (10) |

where CBTmin is as described above, φref = 0.97, and φxcx is defined as the polar phase angle between the state variables x and xc such that

| (11) |

Incorporation of light into melatonin model

To incorporate an effect of light into the melatonin model, the AANAT activity, A(t), in Equation 3 was redefined as:

| (12) |

where m is a constant whose value was determined by parameter fitting to the Intermittent Bright Light dataset and validated on the 1-Pulse Intensity Response Curve dataset.

A phase relationship was derived to compare the results of the model to melatonin and CBT data in humans. CBTmin and melatonin SynOn and SynOff were calculated from the initial CR data from the 3-Pulse Phase-Resetting Protocol and the Intermittent Bright Light dataset.

Parameter Fitting

Parameter fits to the data were derived by a similar method to the one described in the original publication (14). The following equation is used to relate the model predictions to plasma melatonin data:

| (13) |

where H2(ti) is the plasma melatonin level at time ti and εi is an approximate Gaussian random variable with mean 0 and variance determined by the melatonin immunoassay.

The objective is to estimate θ, where

| (14) |

The −2 log-likelihood of the model is

| (15) |

where

| (16) |

The maximum likelihood estimate of θ, θ̂, is computed by minimizing the likelihood. However, in the original model, a Bayesian analysis was used to calculate . This analysis was based on the counts per minute recorded from the immunoassay. These data were not available for this analysis, nor are they available for many clinical applications. Therefore, we derived from the intra-assay coefficient of variance obtained from the laboratory at which the melatonin immunoassays were run.

To integrate this model with an existing mathematical model of the effect of light on the human circadian pacemaker (16) so that it can predict synthesis onset and offset under a variety of simulated protocols, it is necessary to assign average parameter values to βIP, βCP, α, λ, and A. We used the CR data from the Intermittent Bright Light dataset and the 3-Pulse Phase-Resetting Protocol. The individual fits of these 51 subjects were calculated using the parameter fitting method described above and each parameter was averaged across subjects to determine the average parameter value. The final average parameter estimates (mean ± s.e.m.) are: βIP= 0.047 ± 0.004, βCP = 0.025 ± 0.002, α=0.067 ± 0.365, λ =0.588 ± 0.113, and A = 4.834 ± 0.038. The parameter value of m in Equation 12 was determined by a best-fit to the Intermittent Bright Light dataset. A value of m = 7 was found to provide the best fit for all subjects.

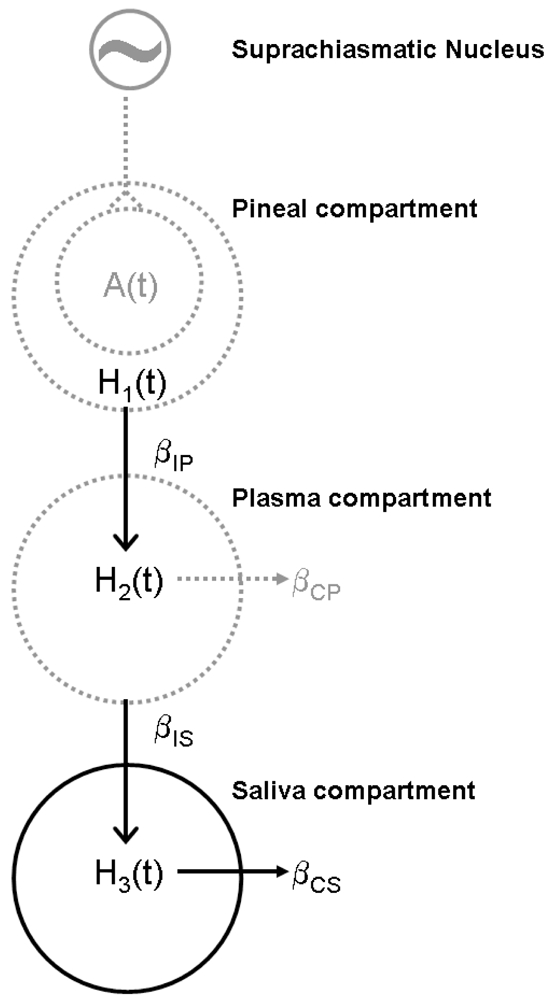

Saliva Compartment

The design of the saliva compartment was modeled by the same principles as the pineal and plasma compartments were created in the original mathematical model of melatonin. It is assumed that all melatonin is released from the pineal gland into the plasma (32). In the plasma, melatonin partially binds to albumin and is eventually cleared through the liver. Melatonin that does not become bound to albumin readily diffuses into the saliva (33). Melatonin in the saliva is eventually cleared through unknown processes. A third equation is added to account for the infusion of melatonin from the plasma into the saliva compartment and for the clearance from saliva. This equation is:

| (17) |

where βIS is the rate of infusion from the plasma to the saliva compartment and βCS is the rate of clearance from the saliva. The plasma compartment equation (Equation 1) has also been modified to include the infusion from the plasma to the saliva. This equation is:

| (18) |

A schematic of the model including the saliva compartment is in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the melatonin model adapted from Brown et al. 1997.

Comparison of Model Simulations to Data

To determine which model fit the experimental data better, both the adjusted R2 (R2adj) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) were calculated. R equals the covariance between the experimental data and the model divided by the product of the standard deviation of the experimental data and the standard deviation of the model predictions; R2 therefore has the same units as variance. R2adj is calculated as

| (19) |

where n is the number of samples and k is the number of parameters estimated for each model. The inclusion of “k” in the calculation imposes a penalty for adding new parameters to the model. A higher R2adj indicates a better fit to the experimental data. When the degrees of freedom n − k − 1 was less than or equal to zero, R2 was reported in place of R2adj. The AIC was calculated as n log (σ̂2) + 2k, where σ̂2 is the residual sum of squares, and n and k are defined as in the R2adj calculation (34). Similarly to the R2adj calculation, the “2k” term in the AIC formula imposes a penalty for adding new parameters to a model. A lower AIC indicates a better fit to the experimental data. For the original model (Equations 1–3), k = 7. With the addition of the light suppression term (Equation 12), the number of parameters fit increases to 8. For the salivary melatonin model (Equation 18), two additional parameters were added to the model; therefore, k = 10.

Results

For the 51 subjects from the Intermittent Bright Light dataset and the 3-Pulse Phase-Resetting Protocol, SynOn occurred 8.26 ± 1.58 hr before CBTmin while SynOff occurred 1.28 ± 3.33 hr before CBTmin on average. Thus the time of SynOn is defined as:

| (19) |

where SynOn is the synthesis onset, φref = 0.97, and φxcxon is defined as the polar phase angle between the state variables x and xc of the circadian model such that

| (20) |

Similarly, the time of SynOff is defined as:

| (21) |

where SynOff is the synthesis offset, φref = 0.97, and φxcxoff is defined as the polar phase angle between the state variables x and xc such that

| (22) |

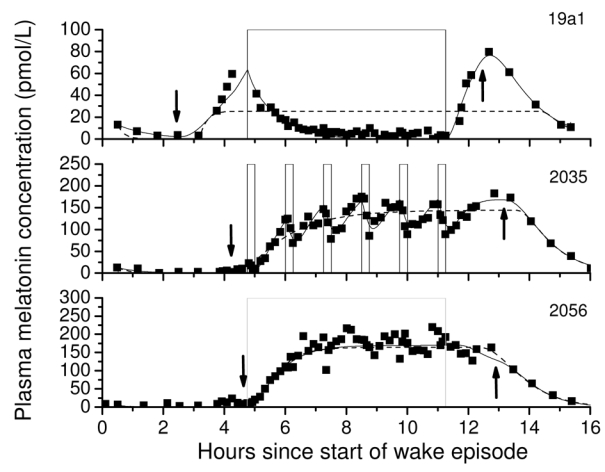

The model was fit to data from the Intermittent Bright Light dataset with CBL, IBL and VDL conditions. While both the original melatonin model and that with the incorporated light effect can predict the data from the continuous VDL condition (Fig. 2, bottom panel), only the latter model can simulate the melatonin suppression of the CBL or IBL conditions (Fig. 2, top and middle panels). Table 1 compares the R2 and AIC of both models with respect to the experimental data for each subject in each condition. SynOn indicates the time when melatonin synthesis onset occurred and SynOff indicates the time when melatonin synthesis offset occurred. A indicates the maximum N-acetyltransferase activity. R2 and AIC are two goodness of fit measures; a higher R2 and a lower AIC indicate a better fit to the data. For subjects in the CBL and IBL conditions, the R2 values increase and the AIC values decrease from the original melatonin model to the model with the incorporated light effect, indicating that the model with the incorporated light effect is a better fit to the data. For the VDL condition, the R2 values are approximately equal for both models, while the AIC increases for the model with the incorporated light effect. Because the light level in this condition is low, the light suppression is not activated; the AIC values increase due to the “2k” parameter penalty in the AIC equation.

Fig. 2.

The melatonin concentration of a subject exposed to a 6.5-hr continuous bright light (CBL) pulse (top panel, ~9500 lux), six 15-min intermittent bright light (IBL) pulses during a 6.5 hour interval (middle panel, ~9500 lux pulses separated by 60-min of <1 lux) and a 6.5-hr continuous dim light (VDL) pulse (bottom panel, <1 lux) compared to the model with the effect of light suppression incorporated (solid lines) and without (dashed lines). Arrows pointing down indicate when predicted SynOn occurs and arrows pointing up indicate when predicted SynOff occurs.

Table 1.

Estimates of the original melatonin model and the model with incorporated light effect to plasma melatonin data from subjects scheduled to a 6.5-hr continuous bright light (CBL), intermittent bright light (IBL) or very dim light (VDL) exposure.

| Original melatonin model | Model with incorporated light effect | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | SynOn (clock hour) | SynOff (clock hour) | A(t) (pmol·L−1· min−1) | R2adj | AIC | SynOn (clock hour) | SynOff (clock hour) | A(t) (pmol·L−1· min−1) | R2adj | AIC |

| Condition BL | ||||||||||

| 19a1v | 20.87 | 8.11 | 1.19 | 0.13 | 3892.12 | 20.2 | 6.10 | 1.29 | 0.96 | 1844.38 |

| 2006v | 20.09 | 21.91 | 7.70 | 0.38 | 5420.69 | 20.01 | 4.17 | 11.28 | 0.98 | 3238.42 |

| 2012v | 5.44 | 7.87 | 3.71 | 0.99 | 3536.74 | 22.96 | 8.03 | 3.71 | 0.99 | 3541.13 |

| 2036v | 4.39 | 8.30 | 4.37 | 0.99 | 3279.80 | 4.43 | 5.78 | 2.06 | 0.99 | 2912.51 |

| 2041v | -- | 20.51 | 1003.11 | −0.30 | 6266.01 | 18.55 | 5.69 | 5.40 | 0.99 | 3172.92 |

| 2043v | 0.76 | 3.16 | 4.05 | 0.82 | 2789.14 | -- | 6.55 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 1958.00 |

| Condition IBL | ||||||||||

| 19b9v | 21.42 | 7.45 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 2376.36 | 22.23 | 7.59 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1852.74 |

| 19c4v | 20.8 | 8.09 | 2.83 | 0.71 | 5178.28 | 20.95 | 7.29 | 8.53 | 0.90 | 4480.78 |

| 2004v | 23.6 | 8.01 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 5752.39 | 23.16 | 8.69 | 11.52 | 0.97 | 4589.86 |

| 2024v | 21.3 | 8.37 | 4.00 | 0.94 | 4631.57 | 21.79 | 7.37 | 3.98 | 0.98 | 3893.72 |

| 2035v | 20.54 | 5.78 | 3.84 | 0.91 | 4035.70 | 20.42 | 5.42 | 3.06 | 0.98 | 3019.08 |

| 19c9v0t2 | 20.62 | 6.72 | 5.66 | 0.81 | 4562.74 | 20.58 | 6.17 | 4.01 | 0.90 | 4151.10 |

| 2042v | 21.76 | -- | 1.14 | 0.93 | 4213.36 | 21.7 | -- | 2.15 | 0.96 | 3783.21 |

| Condition VDL | ||||||||||

| 19b1v | 22.17 | 6.38 | 6.04 | 0.90 | 4507.15 | 22.08 | 7.27 | 3.42 | 0.88 | 4636.21 |

| 19c3v | 22.13 | 5.88 | 4.05 | 0.81 | 5032.53 | 21.84 | 7.25 | 4.26 | 0.82 | 4995.12 |

| 2008v | 21.41 | 2.71 | 2.86 | 0.92 | 3942.86 | 21.31 | 2.17 | 2.68 | 0.92 | 3913.54 |

| 2018v | 22.50 | 7.26 | 4.44 | 0.94 | 4410.99 | 22.3 | 7.83 | 3.85 | 0.93 | 4547.55 |

| 2038v | 19.68 | 20.66 | 11.77 | 0.96 | 3601.56 | 20.33 | 6.45 | 10.81 | 0.87 | 4474.42 |

| 2039v | 20.09 | 23.39 | 1.59 | 0.94 | 3665.99 | 20.21 | 5.16 | 4.42 | 0.90 | 3988.82 |

| 2056v | 23.10 | 6.55 | 3.49 | 0.96 | 3710.22 | 22.97 | 7.14 | 2.94 | 0.96 | 3697.57 |

“--“ indicates that data were missing or that an accurate value could not be obtained.

This model was validated by fitting the model to data from the 1-Pulse Intensity Response Curve Protocol with m = 7 as found by fits to the Intermittent Bright Light dataset as described above. Fig. 3 plots the melatonin suppression calculated from the model fits as a function of light intensity. The predicted melatonin suppression data for each subject were fit with a 4-parameter logistic function. The original experimental data reported in (9) has been superimposed onto Fig. 3 for comparison. Zeitzer et al. reported a half-maximal light intensity of 106 lux with saturation of the melatonin suppression response occurring at ~200 lux and minimal suppression occurring below 80 lux, with variable response between these two lux levels. Similarly, the model predicts a half-maximal response at 96 lux with saturation of the melatonin suppression response at ~200 lux.

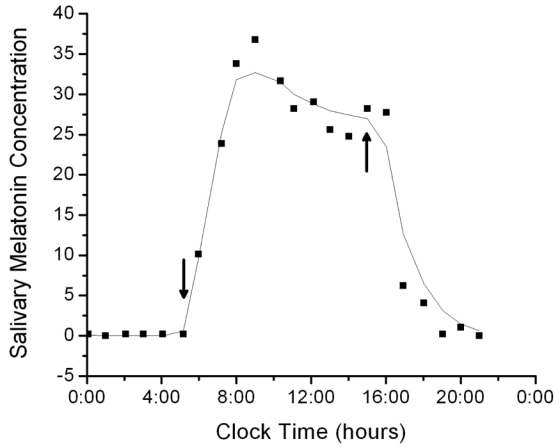

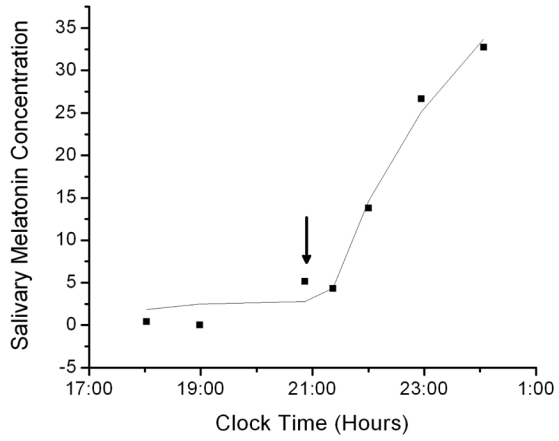

The data from one blind subject from the Salivary Melatonin Concentration dataset are plotted in Fig. 4 against model predictions. Table 2 reports the R2, SynOn and SynOff for each subject in whom a full salivary melatonin profile was available. Table 2 also reports the SynOn and SynOff values for each subject calculated from plasma melatonin, when available. In general, the AIC values are lower for the salivary than for plasma melatonin data. This does not indicate that the fits by the salivary melatonin model are better; the difference in values may be due to difference in sampling rates of saliva and plasma melatonin concentrations. The salivary melatonin data were also more variable than the plasma data, which may also explain why the R2 values are lower in the salivary melatonin fits.

Fig. 4.

The 24-hr salivary melatonin profile of a blind subject fit by the salivary melatonin model. For these data, the fit had R2 = 0.975 and AIC = 37.009. Arrows pointing down indicate when predicted SynOn occurs and arrows pointing up indicate when predicted SynOff occurs.

Table 2.

Estimates of the model with an incorporated salivary melatonin component to full salivary melatonin profiles compared to estimates of the original plasma melatonin model to full plasma melatonin profiles in the same subjects.

| Salivary | Plasma | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Day of Protocol | SynOn (clock hour) | SynOff (clock hour) | A(t) (pmol·L−1· min−1) | R2adj | AIC | SynOn (clock hour) | SynOff (clock hour) | A(t) (pmol·L−1· min−1) | R2adj | AIC |

| 1138U1T3 | 2 | 5.23 | 7.48 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 27.32 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 1415U7T6 | 4 | 5.14 | 14.9 | 0.28 | 0.96 | 37.01 | 5.93 | 14.48 | 6.85 | 0.94 | 75.52 |

| 10 | 4.98 | 8.99 | 0.3 | 0.49 | 36.53 | 6.01 | 15.49 | 5.61 | 0.96 | 69.34 | |

| 11 | 6.14 | 15.58 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 40.09 | 7.12 | 16.64 | 3.5 | 0.93 | 71.65 | |

| 17 | 6.96 | 10.02 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 45.53 | 6.99 | 17.02 | 3.49 | 0.76 | 80.63 | |

| 18 | 7.91 | 15.43 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 36.76 | 7.1 | 15.6 | 3.35 | 0.92 | 62.22 | |

| 20 | 6.98 | 15.48 | 0.36 | 0.92 | 44.91 | 6.11 | -- | 3.19 | 0.05 | 102.53 | |

| 46 | -- | 11.34 | 0.56 | 0.76 | 53.83 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| 1451U4T4 | 3 | 0.06 | -- | 0.15 | 0.89 | 26.43 | 2.1 | 7.48 | 2.56 | 0.71 | 81.46 |

| 13 | 1.96 | -- | 0.13 | 0.93 | 19.89 | 2 | 7.95 | 6.49 | 0.96 | 83.85 | |

| 1459U4T4 | 6 | 20.09 | 21.12 | 0.4 | 0.32 | 48.6 | 18.03 | 2.95 | 6.22 | 0.98 | 55.12 |

| 1459U5T6 | 2 | 20.02 | 22.97 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 35.46 | 21.06 | 3.56 | 3.96 | 0.96 | 65.87 |

| 6 | 22.49 | 5.35 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 37.75 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| 7 | -- | -- | 0.7 | 0.11 | 64.97 | 22.07 | 3.2 | 6.25 | 0.92 | 61.48 | |

| 1459U5T7 | 5 | -- | 6.75 | 0.2 | 0.93 | 28.08 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 1531U6T6 | 7 | -- | 19 | 3.71 | 0.60 | 72 | 18.01 | 23.93 | 7 | 0.95 | 85.5 |

| 1573U6T2 | 2 | 18.16 | 2.55 | 0.4 | 0.95 | 35.37 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

“--“ indicates that data were missing or that an accurate value could not be obtained.

When only a portion of a melatonin pulse is available for analysis, relative threshold methods such as DLMO25% cannot be used to estimate circadian phase. Often under clinical settings, only the rising portion of a salivary melatonin pulse is obtained, because collecting samples throughout the night would require interrupting the sleep episode. Only the rising portion of the melatonin profile was analyzed for 14 melatonin profiles from 4 subjects in the Salivary Melatonin Concentration dataset. These data were fit by the model to determine whether an accurate estimate of SynOn could be extracted. Since SynOff cannot be estimated from the data, an arbitrary SynOff, equal to the time at which the final available data point was measured, was used in the model, since solving Equation 3 requires toff. Therefore, only θ = (βIP, βCP, βIS, βCS, α λ, A, Synon)was estimated.

The data from one subject are plotted in Fig. 5 against model predictions. Table 3 reports the R2, AIC and SynOn for each subject in which the rising portion of the salivary melatonin concentration was available. In some cases, the SynOn value predicted was not a reasonable estimate of the true clock time at which SynOn would be estimated to occur based on other methods. The possible reasons for this include a poor fitting procedure, a bad choice of initial parameters, data that are too noisy, or not enough data points.

Fig. 5.

The salivary melatonin concentration in a blind subject in which data from the rising portion of the curve only was available fit by the salivary melatonin model with a fixed SynOff value equal to the time of the last recorded concentration. For these data, the fit had R2 = 0.983 and AIC = 18.912. Arrows pointing down indicate when predicted SynOn occurs and arrows pointing up indicate when predicted SynOff occurs.

Table 3.

Estimates of the model with an incorporated salivary melatonin component to the rising portion of the salivary melatonin concentration.

| Subject | Day of Protocol | SynOn (clock hour) | R2 | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1415U7T6 | 7 | 4.30 | 1.00 | 11.56 |

| 8 | 5.60 | 1.00 | 17.42 | |

| 9 | 3.02 | 0.80 | 40.10 | |

| 15 | 5.98 | 0.92 | 39.18 | |

| 16 | 7.05 | 0.97 | 32.48 | |

| 21 | 8.03 | 0.98 | 15.90 | |

| 30 | -- | 0.97 | 23.60 | |

| 31 | -- | 1.00 | 14.00 | |

| 33 | -- | 1.00 | 6.76 | |

| 38 | 3.15 | 1.00 | 9.82 | |

| 1459U5T6 | 5 | -- | 0.79 | 24.23 |

| 1459U5T7 | 10 | 20.87 | 0.98 | 22.91 |

| 11 | -- | 1.00 | 10.12 | |

| 1531U6T6 | 8 | 18.97 | 0.99 | 24.49 |

“--“ indicates that data were missing or that an accurate value could not be obtained.

Another way to assess the model’s ability to calculate SynOn when only the rising portion of a curve is available is to truncate full plasma and salivary melatonin curves and fit the model. A total of 16 full salivary melatonin curves were available for this analysis from the Salivary Melatonin Concentration dataset. The curves were truncated at the peak value of melatonin obtained. Again, an arbitrary SynOff, equal to the time at which the final available data point was measured, was used. Table 4 reports the R2 and the SynOn values estimated from the truncated curves compared to the SynOn values estimated from the full curves. There is larger variability between the two SynOn values, which suggests that a full curve may be necessary to obtain an accurate SynOn.

Table 4.

Estimates of the model with an incorporated salivary melatonin component to the rising portion of full salivary melatonin profiles.

| Subject | Day of Protocol | SynOn (clock hour) estimated from rise only | R2 | AIC | SynOn (clock hour) estimated from full curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1415U7T6 | 4 | 5.15 | 1.00 | 14.04 | 5.14 |

| 10 | 6.27 | 0.97 | 24.08 | 4.98 | |

| 11 | -- | 0.99 | 22.49 | 6.14 | |

| 17 | 6.68 | 0.91 | 32.12 | 6.96 | |

| 18 | -- | 0.91 | 26.78 | 7.91 | |

| 20 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 16.46 | 6.98 | |

| 46 | 8.50 | 1.00 | 20.06 | -- | |

| 1451U4T4 | 3 | 22.98 | 0.96 | 18.73 | 0.06 |

| 13 | 0.19 | 0.96 | 20.05 | 1.96 | |

| 1459U4T4 | 6 | 17.08 | 0.98 | 22.04 | 20.09 |

| 1459U5T6 | 2 | 20.03 | 0.99 | 19.08 | 20.02 |

| 6 | 21.00 | 0.95 | 23.01 | 22.49 | |

| 7 | 20.88 | 0.80 | 32.28 | -- | |

| 1459U5T7 | 5 | -- | 0.99 | 21.96 | -- |

| 1531U6T6 | 2 | 11.42 | 1.00 | 14.24 | -- |

| 7 | 17.02 | 0.98 | 33.47 | -- |

“--“ indicates that data were missing or that an accurate value could not be obtained.

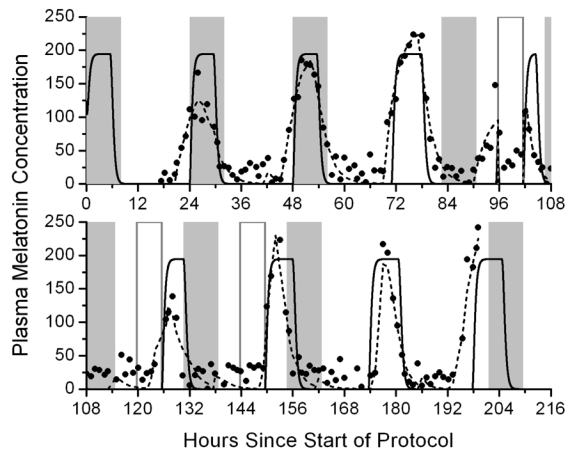

The existing mathematical model of the human circadian pacemaker uses CBTmin as a phase marker of the circadian system, although the CBT rhythm itself is not an output of the model. By incorporating melatonin as both a phase marker and an output rhythm of the circadian pacemaker, the model can predict both phase and melatonin suppression. Fig. 6 is an example of the output of the melatonin model generated by simulating the 3-Pulse Phase-Resetting Protocol, as described above. The phase response to the light stimulus is determined by subtracting initial phase found during the initial pre-stimulus CR from the final phase found during the post-stimulus CR. Additionally, melatonin suppression is observed on the three light exposure days, which affects the estimate of melatonin phase. By incorporating melatonin into our existing model of the circadian pacemaker, the model can predict both melatonin phase and melatonin suppression under a number of experimental protocols.

Fig. 6.

Predictions of the plasma melatonin concentration (solid line, based on average parameter values in the melatonin model equations) in response to a 3-pulse phase resetting protocol. Filled squares indicate measured melatonin concentrations and dashed lines indicate best-fits to the experimental data. Gray bars indicate when scheduled sleep occurs. Open bars indicate scheduled bright light exposure.

Discussion

The original physiologically-based mathematical model of melatonin was able to estimate synthesis onset, offset and amplitude from plasma melatonin samples collected under dim light conditions. We have updated this model to include an effect of ocular light exposure. This model can be used to estimate synthesis onset, offset and amplitude from plasma melatonin samples collected under a variety of lighting conditions, including exposure to intermittent bright light pulses. Phase estimates are often not calculated on light exposure days because threshold methods cannot account for the change in shape and amplitude of the melatonin profile that is observed during the light exposure. However, the model with an incorporated light effect can account for the changes in melatonin concentration observed in response to a light pulse. Furthermore, the additional parameters of the model, including infusion rate of melatonin into the plasma and clearance rate from the plasma, may provide useful information about the dynamics of melatonin suppression by light.

We also added a salivary melatonin compartment to the existing model. The structure of the salivary melatonin compartment is similar to the plasma melatonin compartment and includes rates of infusion from the plasma to saliva and clearance from the saliva. Thus, this model can be used to estimate synthesis onset, offset and amplitude from salivary melatonin samples when plasma melatonin samples have not been collected. Because full salivary melatonin profiles are not always available, we additionally tested whether the model was able to predict accurately the synthesis onset from the rising portion of salivary melatonin only. As can be seen in Table 4, the results of this analysis were inconclusive: for some melatonin pulses analyzed, the SynOn estimates obtained from the rising portion of the curve were within 2 minutes of the SynOn estimates obtained from the full curve. For other melatonin pulses, this was not the case. Further analysis with a larger set of data is necessary. The updated melatonin model was incorporated into an existing model of the circadian pacemaker. The original model of the circadian pacemaker reported CBTmin as the phase marker; however, melatonin is the preferred marker rhythm and most experimental results are reported using melatonin. Therefore, the addition of this melatonin model to the circadian pacemaker model facilitates comparisons of experimental results to model predictions. Additionally, melatonin suppression by light is often used to evaluate the sensitivity of the pacemaker to varying durations, timings and intensities of light. This model of the circadian pacemaker can predict melatonin suppression as well as phase shifts of the melatonin rhythm.

In the original publication of the melatonin model (14), it was reported that estimates of synthesis onset and offset were comparable to melatonin phase markers estimated by threshold methods. Because existing threshold methods depend on the shape and amplitude of the melatonin pulse, they are not adequate measures to estimate phase under experimental conditions in which the shape and amplitude of the melatonin profiles changes. We propose that a physiologically-based method to estimate melatonin phase is more appropriate because these changes in shape and amplitude are considered in the parameters of the model. Furthermore, this method of analysis can provide additional information about the melatonin profile that cannot be measured with threshold-based methods.

Many studies have shown that melatonin suppression by light (10) (11) (12) (13), as well as circadian phase-shifting measured from the melatonin rhythm (12) (35) (36) (37), is differentially sensitive to light wavelength. In particular, action spectra that have been constructed from melatonin suppression data reveal peak sensitivity around 460 nm (10) (11) Future work on the circadian model will include the incorporation of wavelength of light information to predict the effect of narrowband and broadband monochromatic light stimuli on melatonin suppression and melatonin phase shifts.

A user-friendly version of the model detailed in this paper is available for download at: http://dsm.bwh.harvard.edu/bmu/melatonin/ or can be obtained directly from the author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jeanne F. Duffy and Charles A. Czeisler for the use of their data. This work was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Cooperative Agreement NCC9-58 with the National Space Biomedical Research Institute HPF 00203 and HPF 00405 and by NASA Grant NAG69-1035. The experimental studies were performed in a General Clinical Research Center supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant MO1-RR02635, NIA-1-R01-AG06072 from the National Institute on Aging and NIMH-1-R01-MH45130 from the National Institute of Mental Health. EBK is supported by NIH K02-HD045459. CG is supported by FP6-EUCLOCK

References

- 1.Klerman EB, Gershengorn HB, Duffy JF, Kronauer RE. Comparisons of the variability of three markers of the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:181–193. doi: 10.1177/074873002129002474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendt J. Melatonin: characteristics, concerns, and prospects. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20(4):291–303. doi: 10.1177/0748730405277492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gronfier C, Wright KP, Jr, Kronauer RE, Jewett ME, Czeisler CA. Efficacy of a single sequence of intermittent bright light pulses for delaying circadian phase in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E174–E181. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith KA, Schoen MW, Czeisler CA. Adaptation of human pineal melatonin suppression by recent photic history. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3610–3614. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Coevorden A, Mockel J, Laurent E, et al. Neuroendocrine rhythms and sleep in aging men. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:E651–E661. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.4.E651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeitzer JM, Daniels JE, Duffy JF, et al. Do plasma melatonin concentrations decline with age? Am J Med. 1999;107:432–436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klerman EB, Shanahan TL, Brotman DJ, et al. Photic resetting of the human circadian pacemaker in the absence of conscious vision. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:548–555. doi: 10.1177/0748730402238237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein DC, Moore RY. Pineal N-acetyltransferase and hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase: Control by the retinohypothalamic tract and the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res. 1979;174:245–262. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90848-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeitzer JM, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE, Brown EN, Czeisler CA. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: Melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J Physiol (Lond) 2000;526(3):695–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brainard GC, Hanifin JP, Greeson JM, et al. Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: Evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21(16):6405–6412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06405.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thapan K, Arendt J, Skene DJ. An action spectrum for melatonin suppression: Evidence for a novel non-rod, non-cone photoreceptor system in humans. J Physiol. 2001;535(1):261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright HR, Lack LC. Effect of light wavelength on suppression and phase delay of the melatonin rhythm. Chronobiol Int. 2001;18(5):801–808. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100107515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cajochen C, Munch M, Kobialka S, et al. High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1311–1316. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown EN, Choe Y, Shanahan TL, Czeisler CA. A mathematical model of diurnal variations in human plasma melatonin levels. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E506–E516. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.3.E506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voultsios A, Kennaway DJ, Dawson D. Salivary melatonin as a circadian phase marker: Validation and comparison to plasma melatonin. J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12(5):457–466. doi: 10.1177/074873049701200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronauer RE, Forger DB, Jewett ME. Quantifying human circadian pacemaker response to brief, extended, and repeated light stimuli over the photopic range. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14(6):500–515. doi: 10.1177/074873099129001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissbach H, Redfield BG, Axelrod J. Biosynthesis of melatonin: enzymic conversion of serotonin to N-acetylserotonin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960;43:352–353. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelrod J, Weissbach H. Enzymatic O-methylation of N-acetylserotonin to melatonin. Science. 1960;131:1312. doi: 10.1126/science.131.3409.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollag MD, Morgan RJ, Niswender GD. Route of melatonin secretion in sheep. <None Specified>. 1978;673(684):2048–28416. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardinali DP, Lynch HJ, Wurtman RJ. Binding of melatonin to human and rat plasma proteins. Endocrinology. 1972;91:1213–1218. doi: 10.1210/endo-91-5-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopin IJ, Pare CMB, Axelrod J, Weissbach H. The fate of melatonin in animals. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:3072–3075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gronfier C, Wright KP, Jr, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Entrainment of the human circadian pacemaker to longer-than-24h days. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(21):9081–9086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702835104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown EN, Czeisler CA. The statistical analysis of circadian phase and amplitude in constant-routine core-temperature data. J Biol Rhythms. 1992;7:177–202. doi: 10.1177/074873049200700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy JF. Constant Routine. In: Carskadon MA, editor. Encyclopedia of Sleep and Dreaming. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1993. pp. 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffy JF, Wright KP., Jr Entrainment of the human circadian system by light. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20(4):326–338. doi: 10.1177/0748730405277983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gronfier C, Wright KP, Jr, Czeisler CA. Time course of melatonin suppression in response to intermittent bright light exposure in humans. Journal of Sleep Research. 2002 Jun;11(Supplement 1):86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy JF, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Phase-shifting human circadian rhythms: Influence of sleep timing, social contact and light exposure. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;495(1):289–297. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klerman EB, Rimmer DW, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE, Rizzo JF, III, Czeisler CA. Nonphotic entrainment of the human circadian pacemaker. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R991–R996. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.r991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kronauer RE. A quantitative model for the effects of light on the amplitude and phase of the deep circadian pacemaker, based on human data. In: Horne J, editor. Sleep ‘90, Proceedings of the Tenth European Congress on Sleep Research; Dusseldorf: Pontenagel Press; 1990. pp. 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jewett ME, Rimmer DW, Duffy JF, Klerman EB, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Human circadian pacemaker is sensitive to light throughout subjective day without evidence of transients. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1800–R1809. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.r1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May CD, Dean DA, II, Jewett ME. A new mathematical definition of CBTmin improves model predictions of the effect of light on the circadian pacemaker in amplitude suppression protocols. Society for Research on Biological Rhythms. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iguchi H, Kato KI, Ibayashi H. Melatonin serum levels and metabolic clearance rate in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;54:1025–1027. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-5-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennaway DJ, Voultsios A. Circadian rhythm of free melatonin in human plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1013–1015. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson DR, Burnham KP, Thompson WL. Null hypothesis testing: problems, prevalence, and an alternative. J Wildl Dis. 2000;64:912–923. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lockley SW, Brainard GC, Czeisler CA. High sensitivity of the human circadian melatonin rhythm to resetting by short wavelength light. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(9):4502–4505. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warman VL, Dijk DJ, Warman GR, Arendt J, Skene DJ. Phase advancing human circadian rhythms with short wavelength light. Neurosci Lett. 2003;342:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright HR, Lack LC, Kennaway DJ. Differential effects of light wavelength in phase advancing the melatonin rhythm. J Pineal Res. 2004;36(2):140–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-079x.2003.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]