Abstract

The neurocircuitry mediating the emetic reflex is still incompletely understood, and a key question is the degree to which central and/or peripheral components contribute to the overall vomiting mechanism. Having previously found a significant peripheral component in neurokinin NK1-receptor mediated emesis, we undertook this study to examine the putative central component. Adult least shrews were injected intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) with saline or the blood-brain barrier impermeable toxin, Stable Substance P-saporin (SSP-SAP), which ablates cells expressing NK1 receptors. After three days, shrews were challenged intraperitoneally (i.p.) with the emetogenic NK1 agonist GR73632 at different doses and vomiting and scratching behaviors quantified. Ablation of NK1-bearing cells was verified immunohistochemically. Although SSP-SAP injection reduced emesis at 2.5 and 5 mg/kg GR73632 doses, no injections completely eliminated emesis. These data demonstrate that there is a major central nervous system component, and minor peripheral nervous system component, to tachykinin-mediated vomiting. Side effects of the current generation of antiemetics could potentially be reduced by improving bioavailability of the drugs in the more potent central nervous system compartment while reducing bioavailability in the less potent peripheral compartment.

Keywords: Emesis, Saporin, Solitary Tract Nucleus, Substance P, Tachykinin, Vagus

INTRODUCTION

Emesis is an anatomically complex reflex which prevents intoxication through gastrointestinal (GI) absorption. The emetic reflex arc is responsive to a wide variety and time-course of perturbations, and thus requires extensive integration of sensory afferents to generate one complex motor pattern – a retroperistaltic contractile wave in the GI tract, followed by relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and finally a powerful contraction of intracostal and diaphragmatic muscles which expel the toxins (Travagli, Hermann, Browning, & Rogers, 2006; Veyrat-Follet, Farinotti, & Palmer, 1997). Despite significant work, major gaps exist in our knowledge of the emetic control circuits which are partly responsible for the incomplete ability of current clinical antiemetics to block chemotherapy-induced vomiting (CIV) (Jordan, Schmoll, & Aapro, 2007; Roila & Fatigoni, 2006; Hesketh, 2008) when compared to animal model studies of the same compounds.

CIV is also pharmacologically complex. Serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), Substance P (SP), and certain prostanoids are proemetic (Cubeddu, Hoffmann, Fuenmayor, & Malave, 1992; Darmani et al., 2008; Darmani, Zhao, & Ahmad, 1999; Hesketh et al., 2003; Kan, Jones, Ngan, & Rudd, 2002). Although SP is a well-known primary neurotransmitter in signaling of various noxious stimuli via NK1 receptors (NK1R’s) (Andrews & Rudd, 2004), it has emerged as an emetic modulator over the past two decades. NK1R’s are found throughout the brain and GI tract, especially in anatomical substrates of emesis, including the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) of the medulla, enteric nervous system (ENS), and intestinal enterochromaffin (EC) cells (Holzer & Holzer-Petsche, 1997a, 1997b; Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000; Yip & Chahl, 2001).

The DVC is a key central mediator of CIV. This area includes the area postrema (AP), the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNX), which produces outputs to the ENS and GI tract, and the medial solitary tract nucleus (NTS), where emetic signals from numerous brain nuclei and the vagus nerve are integrated. However, central control of CIV is not exclusive. Peripherally-localized components modulate CIV, including 5-HT release from EC cells (Hawthorn, Ostler, & Andrews, 1988; Wang, Martinez, Kimura, & Tache, 2007). Indeed, peripherally administered, brain-impenetrant quaternary analogs of 5-HT will induce vomiting in shrews (Darmani, 1998). Although current thought suggests CNS penetration is required for NK1R antagonist antiemetic efficacy (Andrews & Rudd, 2004), some CNS-impermeant variants can prevent emesis produced by systemic cisplatin (Minami et al., 1998), and reduce peripherally-mediated discharge of vagal afferents (Minami et al., 1998; Minami et al., 2001). As mentioned, Minami et al. (1998) noted that the modified peptide and NK1R antagonist sendide behaved like similar medium sized, charged molecules, and did not seem to cross the blood-brain barrier. SP itself is also a moderately charged peptide, and has been shown to require active transport to cross the barrier (Freed, Audus, & Lundte, 2002). SSP-SAP is a modified, charged variation on the SP peptide also, and should thus be restricted to the biological compartment into which it is injected without active transport. Indeed, SSP-SAP is based on the SP analogue Sar-Met-SP, which is unable to bind the SP transporter (Chappa, Audus, & Lunte, 2006). Interestingly, systemically administered NK1R antagonists were effective antiemetics in ferrets, but did not reduce centrally-mediated foot-tapping behavior produced by SP analogs in gerbils (Rupniak et al., 1997). Thus, the question of central vs. peripheral tachykinin modulation of CIV remains clouded.

We have previously published data (Darmani et al., 2008) demonstrating a significant rightward shift of the dose-response curve for an NK1R agonist (GR73632) challenge when intestinal NK1R’s were specifically ablated with an intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered cytotoxic analog of SP, Stable Substance P-Saporin (SSP-SAP), in the least shrew. This emesis model organism (Cryptotis parva) has been validated in our lab for a wide variety of emetic stimuli, and is notable for its small size (5g at adulthood) and human-like emetic reactions (e.g. Darmani, 1998; Darmani et al., 2008; Darmani, Zhao, & Ahmad, 1999). To further study the relative contributions of peripheral and central components to the emetic reflex, we selectively ablated NK1R-containing cells in the CNS of the least shrew with SSP-SAP, and then quantified the emetic responses to a GR73632 challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures were performed according to approved Western University IACUC protocols and NIH guidelines. Female least shrews (5g average weight, N=38) were housed in a 14:10 L:D cycle and given food and water ad lib. Four groups of 6–9 shrews were injected i.c.v. using a 2 µl Hamilton syringe attached to a 1 cm long, 32 gauge steel tube with a sharpened end. The shrew was anesthetized with isoflurane and laid flat, ventral side down, next to a ruler. Previously published studies (Darmani, Mock, Towns, & Gerdes, 1994) determined that coordinates of 13 mm back from the tip of the nose, and on the midline, produced a reliable intraventricular injection in the rostromedial portion of the lateral ventricle. Each shrew was injected with 500 nl of either physiological saline or 1.2 mg/ml SSP-SAP (0.6 µg; Advanced Targeting Systems; San Diego, CA) over approximately 20–25 sec, and the needle then held in place for another 20 seconds. The wound was dabbed with antibiotic ointment, and the shrew returned to its cage and allowed to recover. In addition, one group was injected with SSP-SAP i.c.v., as well as receiving an injection of 4 µl (4.8 µg) SSP-SAP (diluted in 50 µl saline) i.p. on the same day. The i.p. injection was directed towards the jejunal intestine as described previously (Darmani et al., 2008). Finally, 2 shrews each were injected i.c.v. with unconjugated saporin (U-SAP; 1.3 mg/ml) or SAP conjugated to a nonspecific peptide sequence (blank-SAP; 1.2 mg/ml) as controls for specificity of SSP-SAP targeting and toxicity.

Initial studies indicated that i.p. injections of SSP-SAP were lethal (lack of fresh feces in the cage suggested a loss of intestinal motility, but this was not confirmed by necropsy) on or about the latter portion of the 5th day post-injection, so all studies were conducted on the third day post-SSP-SAP injection. Mortality came rapidly such that by day 6, all (100%) i.p. SSP-SAP injected animals in the pilot studies had either died, or were demonstrating behavioral signs of severe sickness and were euthanized. However, no i.c.v. SSP-SAP or control animals showed signs of illness or died. Also, on days 3 and 4, behavioral observation by trained observers could detect no differences (i.e. behavioral signs of illness) between groups, nor was there significant weight loss (or gain) by day 4. SSP-SAP injected (i.p.) shrews weighed 5.2 ± 1.1g on day 0 vs. 5.0 ± 1.3g on day 4. For comparison, vehicle injected (i.p.) shrews weighed 5.0 ± 0.8g on day 0 vs. 5.1 ± 0.9g on day 4. In this study, immediately following behavioral testing, animals were euthanized with pentobarbital for tissue recovery (see below), so no animals had progressed to signs of illness.

The dose-response relationship of the NK1R agonist GR73632 (0, 1, 2.5 or 5 mg/kg dissolved in saline, i.p., N = 6–9 per group) was generated for shrews pretreated with i.c.v. saline. The responses of SSP-SAP-pretreated shrews to the same doses of GR73632 were then quantified. Thus, individual shrews received one pair of injections – saline or SSP-SAP, then one dose of GR73632. The SSP-SAP and saline-injected shrews were divided into different groups on day 3 post-injection, and each group injected i.p. with one of the above doses of GR73632. Thirty minutes prior to injection, shrews were placed in individual testing boxes and fed 4 mealworms (Tenebrio sp.). Following injection, each shrew was monitored for 30 min, and vomiting and scratching behaviors quantified as described previously (Darmani et al., 2008). Shrews were then perfused as described below for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, and brain and gut harvested. U-SAP-injected and blank-SAP-injected shrews were perfused three days post-injection, and brain and gut harvested.

After behavioral quantification, shrews were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). Fixative (4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was transcardially perfused for 10 min, then the brain was excised from the cranium and placed in 30% sucrose in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB) overnight. A 2 cm length of small intestine approximately 1.5 cm from the stomach was removed and cleaned with saline. A 0.5 cm segment of the distal end of the small intestine was also removed and cleaned. Both segments were cryoprotected with the brain in sucrose/PB. Tissue pieces were embedded in blocks of 12% gelatin/30% sucrose in PB, then cut on a Leica freezing benchtop microtome into 5 sagittal series of 30 µm sections and stored in PB with 0.05% sodium azide.

IHC was performed for mouse anti-NK1 receptor monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; 1:600). IHC for NK1R was also done on the U-SAP- and blank-SAP-injected shrews to verify the targeting specificity of the SSP-SAP lesion. The protocol utilized the avidin-biotin-complex technique, with diaminobenzidine as the chromogen, and has been described elsewhere (Darmani et al., 2008; Ray & Darmani, 2007). A few brain sections from a coronally-sectioned naïve animal were processed together with each brain utilized in this study to serve as a positive IHC control. Sections were mounted on gelatin-subbed slides, air-dried, dehydrated in ascending alcohols and xylene, and coverslipped under DEPEX (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Sections were analyzed by an observer blind to the condition of the slide, and the DVC was identified using an atlas produced in lab (Ray & Darmani, 2007). The presence of any NK1R immunoreactivity (NK1R-IR) in the DVC was considered an incomplete lesion and grouped separately from complete lesions. However, the 500 nl volume caused complete lesions in all but 2 shrews, which subsequent analysis had shown to have intrastriatal and not i.c.v. SSP-SAP injections. These animals’ data were discarded from their respective groups prior to behavioral analysis. Intestine sections were analyzed for intact cell bodies with NK1R-IR, whose processes extended into the luminal layers of the intestine. Animals in which at least the proximal section of small intestine, if not both sections, showed lost cell bodies and minimal numbers of swollen processes, were considered lesioned for behavioral purposes. Subsequent analysis showed no animals had damage in the distal segment, so success of the lesion was measured using only the proximal small intestine segment.

Sections were analyzed and photomicrographs taken at 1600x1200 pixel digital resolution with a SPOT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments) attached to a PC running version 4.0 of the SPOT software, and mounted to a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope. Images were exported to Adobe Photoshop 7 for addition of overlays, and adjustment of brightness or contrast for printing.

Dose dependence of GR73632-induced vomiting was analyzed using a chi-square analysis of variance (ANOVA). Pairwise comparisons between SSP-SAP groups and the saline control group were made via Fisher’s exact test. Both the proportion of animals vomiting and the frequencies of vomiting and scratching were tested. A p value below 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

RESULTS

IHC following injection of SSP-SAP

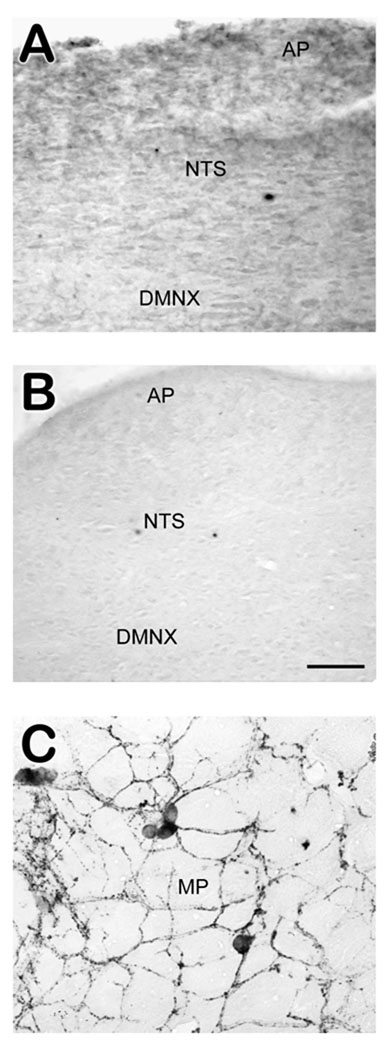

Intracranial injection of SSP-SAP, and not saline, eliminated NK1R-IR in the brainstem, including the DVC (figure 1A–B), but did not affect immunoreactivity in the small intestine (figure 1C). Our previously published report demonstrated that intraperitoneal injections of SSP-SAP resulted in unaffected brainstem NK1R-IR, and eliminated large swaths of NK1R-IR from the small intestine (jejunum) (Darmani et al., 2008). Combined i.p./i.c.v. injections of SSP-SAP replicated the lesions produced by their individual administration (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunolabeling of NK1R-IR following intracerebroventricular injection of saline or SSP-SAP. A) Photomicrograph of the DVC from a shrew given i.c.v. saline. Numerous NK1R-IR labeled cells and dense neuropil were present in the DVC. B) The DVC of a shrew injected with SSP-SAP i.c.v. No immunoreactivity for NK1R-IR was present. C) A segment of the small intestine from the same animal (SSP-SAP injected i.c.v.). Cells are well-stained, morphologically uniform, and demonstrate extensive NK1R-immunopositive fibers, as seen in saline-injected controls. Abbreviations: AP – area postrema; DMNX – dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; MP – myenteric plexus; NTS – nucleus of the solitary tract. Scale bar for all sections = 50 µm.

GR73632-induced emesis and scratching with and without i.c.v. SSP-SAP

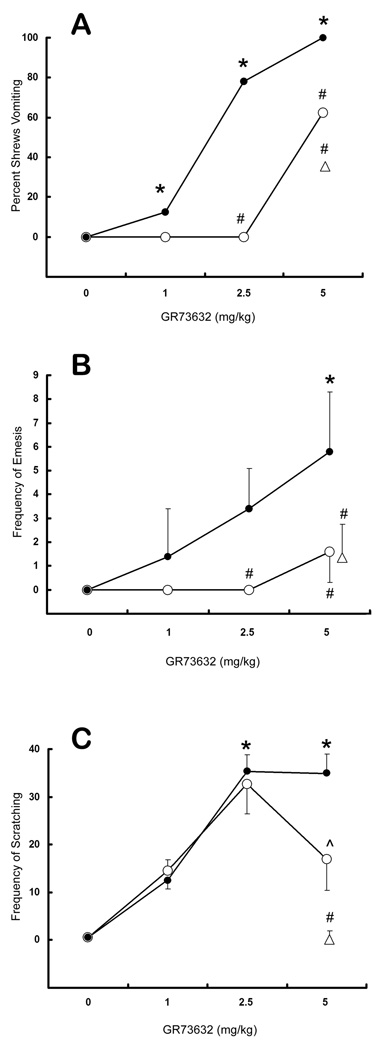

Relative to the vehicle-injected group, injection of GR73632 (i.p.) caused significant (p < .001), dose-dependent increases in vomiting and scratching (figure 2A–C, filled circles) in i.c.v. saline-pretreated controls. Compared to i.c.v. saline injection, intracranial SSP-SAP injection (0.6 µg) significantly reduced (p < .05) the percentage of animals vomiting in response to the 2.5 mg/kg (78% vomiting vs. 0%, respectively) and 5 mg/kg (100% vs. 62.5%, respectively) doses of GR73632 (figure 2A, open circles). The proportion of animals pre-injected with both i.c.v. and i.p. SSP-SAP which vomited in response to 5 mg/kg GR74362 (35.5%) was also significantly reduced compared to i.p. (100%; see Darmani et al., 2008) or i.c.v. (100%) saline-injected controls (figure 2A, open triangle). The frequency of vomiting in response to GR73632 (1, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg) was also significantly (p < .05) attenuated by i.c.v. SSP-SAP at doses of 2.5 mg/kg (0.0 ± 0.0 vomits vs. 3.4 ± 1.7) and 5 mg/kg (1.6 ± 1.3 vs. 5.8 ± 2.5), relative to their corresponding i.c.v. vehicle-injected control groups (figure 2B). In addition, combined i.c.v. and i.p. injections of SSP-SAP significantly reduced vomiting frequency following a 5 mg/kg dose of GR73632 (1.4 ± 1.4 vomits) relative to their i.c.v. (5.8 ± 2.5) or i.p. (13.6 ± 9.2; see Darmani et al., 2008) vehicle-injected control groups (figure 2B, triangle).

Figure 2.

Vomiting and scratching following administration of GR73632 to i.c.v. saline (filled circles) or SSP-SAP (open circles) pre-injected shrews. The open triangles represent a dose of 5 mg/kg GR73632 tested against the combined (i.p./i.c.v.) SSP-SAP injections. In all cases, * represents a statistically significant increase in vomiting or scratching relative to the 0 mg/kg (vehicle) control group (p < 0.05), and # represents a statistically significant decrease in vomiting or scratching relative to the corresponding dose of GR73632 in saline pre-injected controls. (A) The percentage of animals vomiting in response to the various doses of GR73632. (B) The frequency of vomiting (mean ± SEM) in response to GR73632. (C) The frequency of scratches (mean ± SEM) in response to GR73632. The ^ indicates a trend towards a significant decrease in scratching (p < 0.1) relative to the saline pre-injected control group.

No significant effects on scratching were noted for i.c.v. SSP-SAP injections, although a trend (0.05 < p < 0.1) towards reduced scratching was found with 5 mg/kg GR73632 (figure 4C, caret). At the same dose of GR73632, the combined i.c.v./i.p. SSP-SAP injections did significantly reduce the frequency of scratching (0.2 ± 0.14 scratches) relative to both the i.c.v. (34.9 ± 4.1) and i.p. (33.8 ± 3.8) control groups (figure 2C, triangle).

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to help clarify one of the central questions regarding tachykinin-induced emesis: Is the induced vomiting mediated entirely by the CNS, or is there a peripheral component as well? It is already known that serotonin mediates emesis through a mechanism primarily involving peripherally located 5-HT3 receptors (Darmani, 1998), whereas serotonin-mediated scratching and its homologues are mediated centrally via 5-HT2A receptors (Darmani, Mock, Towns, & Gerdes, 1994; Fone, Johnson, Bennett, & Marsden, 1989; Willins & Meltzer, 1997). However, the mechanism of tachykinin-induced vomiting does not completely overlap that of serotonin. In both peripheral (Darmani et al., 2008) and central (this study) injections of the targeted toxin, a rightward shift of the dose-response curve for the percentage of animals vomiting in response to GR73632 was evident. This shift was somewhat greater following central injections, where emesis was completely blocked in all but the highest dose of GR73632. The short survival time following administration of peripheral SSP-SAP, but not central SSP-SAP, or blank- or U-SAP by either administration route, suggests there is a critical role of peripheral SP in the normal GI physiology of the shrew. Further biochemical and physiological studies will be needed to determine the specific role(s) of peripheral SP and the mechanism of lethality related to loss of these tachykinergic elements. Thus, the data presented here and in our previous study (Darmani et al., 2008) suggest that there is indeed a peripheral component to tachykinergic mediation of vomiting, although the central component appears much more influential in the overall process.

SSP-SAP has been demonstrated to be both specific and effective as a targeted ablation tool (Nattie & Li, 2006; Wiley & Lappi, 1999). The inherent advantage of the very small size of our emetic animal model, the least shrew, and of the impermeability of the blood-brain barrier to large peptides/proteins, provided a route to lesion only the peripheral NK1R-containing cells in the GI tract, while still being able to lesion only the central NK1R-containing elements as well. The dose-dependence of GR73632-induced emesis in the saline-injected control animals, and the lack of effect of saline injections (even i.c.v.), demonstrated that emesis was being induced physiologically and not through a nonspecific pharmacological effect.

The specificity of the lesion to the periphery, and effectiveness of the central lesion, was verified by immunohistochemical labeling and by quantifying scratching behavior, which is analogous to foot-tapping in gerbils (see Introduction) and mediated centrally by NK1 receptors (Darmani et al., 2008; Ravard, Betschart, Fardin, Flamand, & Blanchard, 1994). As mentioned, previous work has shown that SP requires active transport across the blood-brain barrier, and that some analogues including SSP cannot bind this transporter (see Introduction). Based on our immunohistochemical labeling results, in which there was no visual evidence of lost NK1R’s in the uninjected compartment, SSP-SAP cannot bind the transporter either. Furthermore, scratching was not significantly affected by peripheral SSP-SAP injection (Darmani et al., 2008), supporting the specificity of the peripheral lesion. Although centrally-injected SSP-SAP did not significantly suppress scratching without co-injection of SSP-SAP intraperitoneally (which obliterated the behavior), there was a trend towards reduced scratching. It is possible that the poor central suppression was related to the anatomical loci mediating scratching being too distant from the i.c.v. injection site to be fully lesioned. Indeed, evidence implicates a spinal locus for scratching behavior (Fone et al., 1989), which would be difficult to fully lesion without intrathecal injections. In addition, the fact that scratching was eliminated by co-injection of SSP-SAP in both physical “compartments”, but not in either compartment alone, suggests that a peripheral component to tachykinin-induced scratching behavior is present. This component could be related to the well-known role of SP in nociception. Specific ablation of NK1 receptors in brain or spinal nuclei involved in nociceptive transmission may potentially clarify the scratching data presented here.

Based on our actual lesions, the loss of NK1R elements in the CNS was a much more potent antiemetic than the loss of peripheral elements. Despite the complexity of the reflex, many studies have converged on the medullary DVC as a critical locus for SP emesis mediation (Andrews et al., 2000; Ito et al., 2003; Miller & Ruggiero, 1994; Reynolds, Barber, Grahame-Smith, & Leslie, 1991; Van Sickle, Oland, Mackie, Davison, & Sharkey, 2003). Thus, it was expected that ablation of central NK1R elements in the DVC would inhibit SP-mediated emesis. While this was indeed the case, central delivery of SSP-SAP still failed to completely eliminate emesis, even though vomiting was induced with an NK1R-specific agonist. This finding correlates with recently published data from our lab which demonstrated increased levels of SP in both the CNS and jejunum following cisplatin-induced vomiting (Darmani, Crim, Janoyan, Abad, & Ramirez, 2009), suggesting a combined central/peripheral mechanism for SP-mediated emesis. However, it has also been shown that SP can be actively transported across the blood-brain barrier (Darmani et al., 2008; Freed, Audus, & Lundte, 2002), so there remains the possibility that SP produced peripherally as a consequence of vomiting is still acting centrally. Furthermore, it is also possible that although most immunoreactivity was eliminated following toxin administration, there was a small but functional proportion of surviving NK1R-containing cells. Interestingly, combined central and peripheral injections were hardly more effective than their individually-administered counterparts. While this would at first glance conflict with the data suggesting a facilitatory role for peripheral NK1 receptor activation, it is equally likely that the peripheral NK1R mediation is secondary to, and possibly dependent on, the central NK1R mediation.

Finally, it should be noted that the relative strength of the central effects seen in this study are specific to tachykininergic modulation of emesis, and could be specific to the least shrew as well. Emesis mediated by serotonin, as mentioned, contains both peripheral and central components. In that case, though, the peripheral component is much more influential than the central component (Darmani, 1998; Darmani & Johnson, 2004). Although there is evidence for colocalization of SP with serotonergic neurons (Elliott, Mason, Graham, Turpin, & Hagan, 1992; Thor & Helke, 1989), the behavioral and pharmacological data presented in this study and in our previous work (Darmani et al., 2008) strongly suggest that the relative influence of the central and peripheral components are reversed in tachykininergic mediation of vomiting. A question remains, however, in the degree to which any emesis model can be extrapolated to human vomiting behavior. Species differences are important in emesis – rodents, for example, do not even have an emetic reflex. Previous studies have used various larger animals, including musk shrews, dogs, and ferrets, but each animal model has its own deviations from the comparable emetic responses seen in human behavior (Andrews and Rudd, 2004; Carpenter, Briggs, & Strominger, 1984; Gardner et al., 1994; Ito et al., 1995). In spite of these differences, much of the work done in other animal models has been successfully translated into the clinic, as evidenced by the effective prevention of emesis caused by the moderately emetogenic chemotherapeutic agents when a new-generation “setron” 5-HT3R antagonist is added to the treatment regimen (for review, see Hesketh, 2008). Thus far and despite its small size, the least shrew has demonstrated sensitivities and emetic responses in line with those seen in humans (e.g. Darmani, 1998; Darmani et al., 2008; Darmani, Zhao, & Ahmad, 1999), suggesting that while some species differences may eventually be found, the least shrew can serve at least as well as, if not better than, the currently available animal emesis models.

In conclusion, this study has provided evidence for both central and peripheral modulation of the emetic reflex by NK1 receptors in the least shrew. This network is organized in such a way that the central components have primacy over the peripheral components, and little to no additive or synergistic effects occur upon lesion of both parts of the network. Further research will be necessary to determine whether this is true for all proemetic neurotransmitter networks, or only for the tachykininergic network. However, determining the relative contribution of peripheral versus central modulation will be useful in developing antiemetics that are more potent and/or easier to administer, or that are effective faster and with fewer side effects than current treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant #R01CA115331 from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Darmani.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/bne.

REFERENCES

- Andrews PL, Okada F, Woods AJ, Hagiwara H, Kakaimoto S, Toyoda M, Matsuki N. The emetic and anti-emetic effects of the capsaicin analogue resiniferatoxin in Suncus murinus, the house musk shrew. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;130(6):1247–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PLR, Rudd JA. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 164. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2004. The role of tachykinins and the tachykinin NK1 receptor in nausea and emesis; pp. 359–440. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter DO, Briggs DB, Strominger N. Behavioral and electrophysiological studies of peptide-induced emesis in dogs. Federation Proceedings. 1984;43(15):2952–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappa AK, Audus KL, Lundte SM. Characteristics of substance P transport across the blood-brain barrier. Pharmaceutical Research. 2006;23(6):1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-0068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubeddu LX, Hoffmann IS, Fuenmayor NT, Malave JJ. Changes in serotonin metabolism in cancer patients: its relationship to nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. British Journal of Cancer. 1992;66(1):198–203. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA. Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists prevent cisplatin-induced emesis in Cryptotis parva: a new experimental model of emesis. Journal of Neural Transmission. 1998;105(10–12):1143–1154. doi: 10.1007/s007020050118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Crim JL, Janoyan JJ, Abad J, Ramirez J. A re-evaluation of the neurotransmitter basis of chemotherapy-induced immediate and delayed vomiting: Evidence from the least shrew. Brain Research. 2009;1248:40–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Johnson JC. Central and peripheral mechanisms contribute to the antiemetic actions of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol against 5-hydroxytryptophan-induced emesis. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;488(1–3):201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Mock OB, Towns LC, Gerdes CF. The head-twitch response in the least shrew (Cryptotis parva) is a 5-HT2- and not a 5-HT1C-mediated phenomenon. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1994;48(2):383–396. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Wang Y, Abad J, Ray AP, Thrush GR, Ramirez J. Utilization of the least shrew as a rapid and selective screening model for the antiemetic potential and brain penetration of substance P and NK(1) receptor antagonists. Brain Research. 2008;1214:58–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Zhao W, Ahmad B. The role of D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in the mediation of emesis in Cryptotis parva (the least shrew) Journal of Neural Transmission. 1999;106(11–12):1045–1061. doi: 10.1007/s007020050222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott PJ, Mason GS, Graham EA, Turpin MP, Hagan RM. Modulation of the rat mesolimbic dopamine pathway by neurokinins. Behavioural Brain Research. 1992;51(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fone KC, Johnson JV, Bennett GW, Marsden CA. Involvement of 5-HT2 receptors in the behaviours produced by intrathecal administration of selected 5-HT agonists and the TRH analogue (CG 3509) to rats. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;96(3):599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed AL, Audus KL, Lundte SM. Investigation of substance P transport across the blood-brain barrier. Peptides. 2002;23(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner CJ, Bountra C, Bunce KT, Dale TJ, Jordan CC, Twissel DJ, Ward P. Antiemetic activity of neurokinin receptor antagonists is mediated centrally in the ferret. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;112:516. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorn J, Ostler KJ, Andrews PL. The role of the abdominal visceral innervation and 5-hydroxytryptamine M-receptors in vomiting induced by the cytotoxic drugs cyclophosphamide and cis-platin in the ferret. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 1988;73(1):7–21. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1988.sp003124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh PJ, Van Belle S, Aapro M, Tattersall FD, Naylor RJ, Hargreaves R, Carides AD, Evans JK, Horgan KJ. Differential involvement of neurotransmitters through the time course of cisplatin-induced emesis as revealed by therapy with specific receptor antagonists. European Journal of Cancer. 2003;39(8):1074–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh PJ. Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(23):2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P, Holzer-Petsche U. Tachykinins in the gut. Part I. Expression, release and motor function. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1997a;73(3):173–217. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P, Holzer-Petsche U. Tachykinins in the gut. Part II. Roles in neural excitation, secretion and inflammation. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1997b;73(3):219–263. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito C, Isobe Y, Kijima H, Kiuchi Y, Ohtsuki H, Kawamura R, Tsuchida K, Higuchi S. The anti-emetic activity of GK-128 in Suncus murinus. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;285(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00372-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Nishibayashi M, Kawabata K, Maeda S, Seki M, Ebukuro S. Induction of Fos protein in neurons in the medulla oblongata after motion- and X-irradiation-induced emesis in musk shrews (Suncus murinus) Autonomic Neuroscience. 2003;107(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(03)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Schmoll HJ, Aapro MS. Comparative activity of antiemetic drugs. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2007;61(2):162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan KK, Jones RL, Ngan MP, Rudd JA. Actions of prostanoids to induce emesis and defecation in the ferret. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;453(2–3):299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone SB, Geraghty DP. Characterization and regulation of tachykinin receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2000;27(11):939–942. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Ruggiero DA. Emetic reflex arc revealed by expression of the immediate-early gene c-fos in the cat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14(2):871–888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00871.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M, Endo T, Kikuchi K, Ihira E, Hirafuji M, Hamaue N, Monma Y, Sakurada T, Tan-no K, Kisara K. Antiemetic effects of sendide, a peptide tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist, in the ferret. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;363(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M, Endo T, Yokota H, Ogawa T, Nemoto M, Hamaue N, Hirafuji M, Yoshioka M, Nagahisa A, Andrews PL. Effects of CP-99, 994, a tachykinin NK(1) receptor antagonist, on abdominal afferent vagal activity in ferrets: evidence for involvement of NK(1) and 5-HT(3) receptors. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;428(2):215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie E, Li A. Neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons in the ventral medulla are essential for normal central and peripheral chemoreception in the conscious rat. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2006;101(6):1596–1606. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00347.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravard S, Betschart J, Fardin V, Flamand O, Blanchard JC. Differential ability of tachykinin NK-1 and NK-2 agonists to produce scratching and grooming behaviours in mice. Brain Research. 1994;651(1–2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90698-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AP, Darmani NA. A histologically derived stereotaxic atlas and substance P immunohistochemistry in the brain of the least shrew (Cryptotis parva) support its role as a model organism for behavioral and pharmacological research. Brain Research. 2007;1156:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DJ, Barber NA, Grahame-Smith DG, Leslie RA. Cisplatin-evoked induction of c-fos protein in the brainstem of the ferret: the effect of cervical vagotomy and the anti-emetic 5-HT3 receptor antagonist granisetron (BRL 43694) Brain Research. 1991;565(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91654-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roila F, Fatigoni S. New antiemetic drugs. Annals of Oncology. 2006;17 Suppl 2:ii96–ii100. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupniak NM, Tattersall FD, Williams AR, Rycroft W, Carlson EJ, Cascieri MA, Sadowski S, Ber E, Hale JJ, Mills SG, MacCoss M, Seward E, Huscroft I, Owen S, Swain CJ, Hill RG, Hargreaves RJ. In vitro and in vivo predictors of the anti-emetic activity of tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonists. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;326(2–3):201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)85415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor KB, Helke CJ. Serotonin and substance P colocalization in medullary projections to the nucleus tractus solitarius: dual-colour immunohistochemistry combined with retrograde tracing. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 1989;2(3):139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Hermann GE, Browning KN, Rogers RC. Brainstem circuits regulating gastric function. Annual Review of Physiology. 2006;68:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle MD, Oland LD, Mackie K, Davison JS, Sharkey KA. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol selectively acts on CB1 receptors in specific regions of dorsal vagal complex to inhibit emesis in ferrets. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2003;285(3):G566–G576. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00113.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrat-Follet C, Farinotti R, Palmer JL. Physiology of chemotherapy-induced emesis and antiemetic therapy. Predictive models for evaluation of new compounds. Drugs. 1997;53(2):206–234. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Martinez V, Kimura H, Tache Y. 5-Hydroxytryptophan activates colonic myenteric neurons and propulsive motor function through 5-HT4 receptors in conscious mice. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2007;292(1):G419–G428. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00289.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley RG, Lappi DA. Targeting neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons with [Sar9,Met(O2)11 substance P-saporin. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;277(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willins DL, Meltzer HY. Direct injection of 5-HT2A receptor agonists into the medial prefrontal cortex produces a head-twitch response in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;282(2):699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J, Chahl LA. Localization of NK1 and NK3 receptors in guinea-pig brain. Regulatory Peptides. 2001;98(1–2):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]