Abstract

Background: Depressive disorders are a major source of disability among low-income mothers in developing countries.

Objectives: The objectives were to examine the association of maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth among infants in rural Bangladesh and to examine how the relation is affected by infant irritability and caregiving practices.

Design: Infant growth was measured among 221 infants at 6 and 12 mo. Mothers reported their depressive symptoms and perceptions of their infant's temperament, and a home observation of caregiving was conducted.

Results: At 6 mo, 18% of infants were stunted (length-for-age <−2 z scores). At 12 mo, 36.9% of infants were stunted; infants of mothers with depressive symptoms had a 2.17 higher odds of being stunted (95% CI: 1.24, 3.81; P = 0.007) than did infants of mothers with few symptoms (45.3% compared with 27.6%). In a multivariate regression analysis, maternal depressive symptoms were associated with 12-mo length-for-age, adjusted for 6-mo length-for-age, maternal education, infant sex, birth order, receipt of iron and zinc, months breastfed, maternal perception of infant temperament, and caregiving observations. Maternal depressive symptoms were not related to 12-mo weight-for-length. The relation between depressive symptoms and infant growth was not moderated by maternal perceptions of infant temperament, but was partially mediated by caregiving.

Conclusions: The finding that infants of mothers with depressive symptoms in Bangladesh experience poor linear growth may extend to other low-income countries with high rates of food insecurity. Interventions to promote growth in infants should include prevention or treatment of maternal depressive disorders and strategies to ensure adequate food security.

MATERNAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS AND INFANT GROWTH IN RURAL BANGLADESH

Maternal depressive disorders are a principal source of disability worldwide, particularly among women in low-income countries (1–3). The societal burden of maternal depressive disorders extends beyond women to the next generation by increasing the risk of problems related to growth and development among infants of depressed mothers (4–6). Infants are particularly vulnerable because they are completely dependent on their caregivers, and their nutritional demands are high to support their rapid growth and development. Not only do infants triple their birth weight by 12 mo of age but they experience rapid brain growth as they acquire specific skills that guide their early development. Infants who experience growth faltering early in life that is severe or prolonged enough to cause stunting (length-for-age < −2 z scores) are at risk of lasting cognitive and academic deficits (7, 8).

Despite the vulnerability that occurs during infancy, the evidence linking maternal depressive symptoms with infant growth is mixed. Studies from India (9–11), Pakistan (12, 13), Vietnam (10), Brazil (14, 15), and Nigeria (16) have shown worse growth among infants of mothers with depressive symptoms than in infants of mothers with few symptoms. In contrast, studies from South Africa (17), Peru (10), Ethiopia (10), and Jamaica (18) have shown no significant differences in infant growth related to maternal depressive symptoms. Comparisons across studies are difficult because the studies varied in design; only 4 of the 13 studies were longitudinal, several studies either did not adjust for potential confounders or had minimal adjustment, and there was limited attention to the potential mechanisms linking maternal depressive symptoms with poor infant growth.

The current investigation was conducted in a low-income, rural community in Bangladesh with relatively high rates of maternal depressive symptoms. In an earlier investigation, we found that depressive symptoms were related to poverty and to social and environmental conditions, such as low education, and that there was synergy between maternal depressive symptoms and mothers' perceptions of their infant as irritable. When both conditions existed, infants experienced delayed cognitive development from 6 to 12 mo, which was partially explained by a lack of responsive stimulation in the home (19). In the current investigation we examined whether the relations we found between maternal depressive symptoms and infant development extended to infant growth. We tested 3 hypotheses. First, we examined whether infants of mothers with depressive symptoms experienced slower growth from 6 to 12 mo than did infants of mothers with few depressive symptoms. Second, we examined whether infants of mothers who reported both depressive symptoms and infant irritability experienced worse growth from 6 to 12 mo than did infants of mothers who reported neither or only one condition. Finally, we examined whether caregiving practices observed in the home mediated the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants

The participants were a subset from a 6-mo, double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial of micronutrient supplementation conducted among infants in the Matlab field research area of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B) (20, 21). Most villages had limited access to electricity, safe water, and sanitary waste disposal; most houses had 1 or 2 rooms with external water, cooking facilities, and latrines.

Procedures

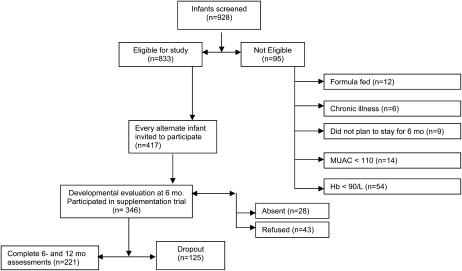

The procedures were approved by the ethical review boards of the ICDDR,B and the University of Maryland, Baltimore. On the basis of demographic information from a Health and Demographic Surveillance System, potentially eligible infants were identified and informed consent was obtained from parents. Research assistants collected socioeconomic and demographic data and measured the infants' weight, length, arm circumference, and hemoglobin concentration. Infants were eligible if they were 6 mo of age, were breastfed, were not severely malnourished or anemic (midupper arm circumference ≥110 mm and hemoglobin ≥90.0 g/L), and had no obvious neurological disorders, physical disabilities, or chronic illnesses. A subset of families was selected by inviting every alternate family to participate in a substudy; 43 families refused and 28 families were absent, which left a sample of 346 families (Figure 1). Infants were randomly assigned to a 5-cell micronutrient supplementation trial, and supplements were given weekly by fieldworkers from 6 to 12 mo (20, 21).

FIGURE 1.

Sample selection. MUAC, midupper arm circumference; Hb, hemoglobin.

Anthropometric data were collected when the infants were 6 and 12 mo of age, and the data were converted to length-for-age and weight-for-length z scores using World Health Organization references (22). At 12 mo, questionnaires on maternal depressive symptoms and infant temperament were administered to mothers orally in Bengali. A trained examiner conducted a 40-min home visit to score the Home Inventory (23). There were 125 families (36%) who did not complete the 12-mo assessment, which left a final sample of 221. Attrition did not vary by supplementation group, sex, maternal education, or anthropometric data.

Measures

Maternal depressive symptoms were measured by using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) (24), which addresses 6 aspects of depression: depressed mood, guilt/worthlessness, helplessness/hopelessness, lethargy/fatigue, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance. Respondents rate the frequency of symptoms from 0 (“rarely or never”) to 3 (“most or all the time”). Higher summed scores indicate more symptoms. The clinical cutoff of 16 was used in descriptive analyses, but because the cutoff has not been validated in Bangladesh, we used the CES-D as a continuous variable to test hypotheses. The internal consistency, measured by coefficient alpha, was 0.94.

Maternal perception of infant temperament was measured by adapting items from the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (25) and the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (26) that represented irritability, such as time crying and soothing difficulty. The language was changed to reflect the local environment and education of the mothers. To simplify response choices, the 7-point scales were shortened to 4 points, ranging from 0 “never” to 3 “all the time”. The items were factor analyzed, and one 9-item factor was extracted representing irritability and accounting for 69% of the variance. Scores for the irritability factor were standardized into z scores; low scores reflected high irritability and high scores reflected low irritability, referred to as easygoing. An early version of the scale administered to mothers of infants in a low-income community in India yielded adequate test-retest reliability (r = 0.68, P < 0.001) and internal consistency (coefficient α = 0.79) (27). Poverty was defined by household income divided by household size; low scores indicated a higher level of poverty. Breastfeeding duration, based on maternal report, was the months of exclusive breastfeeding. Stimulation and support in the home were measured by using the Home Inventory, an observation scale that has been widely used in international child development research and has shown a strong relation with subsequent intellectual and achievement scores (23, 28). In collaboration with an anthropologist, we adapted and tested the Home Inventory to ensure that items were culturally appropriate. Training and interrater reliability were conducted to ensure agreement.

Analysis plan

We conducted 3 descriptive analyses before hypothesis testing. First, we used repeated-measures analysis of variance to examine changes from 6 to 12 mo in length-for-age and weight-for-length between infants of mothers who reported depressive symptoms above and below the clinical range (CES-D > 16 compared with CES-D ≤ 16) at 12 mo (Table 1). Second, we conducted a logistic regression analysis to describe rates of stunting at 12 mo. Finally, we conducted a correlation matrix among the variables of interest: maternal depressive symptoms, infant anthropometric data at 6 and 12 mo, Home Inventory score, maternal perception of infant temperament, maternal education, and poverty (Table 2). All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

TABLE 1.

Anthropometric data at 6 and 12 mo by maternal depressive symptoms measured at 12 mo1

| 6 mo |

12 mo |

||||

| Anthropometric data | Nondepressed2 (n = 105) | Depressed3 (n = 117) | Nondepressed2 (n = 105) | Depressed3 (n = 114) | P for depression × time |

| Length-for-age z score4 | −1.20 ± 0.775 | −1.23 ± 0.83 | −1.54 ± 0.85 | −1.82 ± 0.956 | 0.001 |

| Weight-for-length z score7 | 0.06 ± 0.79 | 0.06 ± 0.92 | −0.76 ± 0.81 | −0.82 ± 0.90 | NS |

There were no significant differences in length-for-age or weight-for-length z scores at 6 mo.

Defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale score <16.

Defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale score ≥ 16.

P = 0.001 for overall decline from 6 to 12 mo (repeated-measures ANOVA).

Mean ± SD (all such values).

Comparision with children of nondepressed mothers at the same time point, P = 0.001 (repeated-measures ANOVA).

P = 0.001 for overall decline from 6 to 12 mo (repeated-measures ANOVA).

TABLE 2.

Pearson's correlation coefficients among maternal depressive symptoms, infant anthropometric data at 6 and 12 mo, Home Inventory score, infant temperament, maternal education, and socioeconomic status1

| Length-for-age |

Weight-for-length |

|||||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 6 mo | 12 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | Home Inventory score | Infant temperament | Maternal Education | |

| Length-for-age at 6 mo | −0.01 | |||||||

| Length-for-age at 12 mo | −0.132 | 0.793 | ||||||

| Weight-for-length at 6 mo | −0.05 | −0.172 | 0.06 | |||||

| Weight-for-length at 12 mo | −0.10 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.543 | ||||

| Home Inventory score | −0.214 | 0.204 | 0.243 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |||

| Infant temperament | −0.234 | 0.05 | 0.132 | 0.10 | 0.184 | 0.194 | ||

| Maternal education | −0.224 | 0.194 | 0.263 | 0.17 | 0.172 | 0.433 | 0.152 | |

| Socioeconomic status | −0.132 | 0.263 | 0.184 | 0.02 | 0.142 | 0.363 | 0.10 | 0.413 |

n = 221.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

To test the first hypothesis that maternal depressive symptoms were related to poor infant growth from 6 to 12 mo, we used multivariate regression analyses to examine length-for-age and weight-for-length z scores at 12 mo, controlling for 6-mo scores and for covariates associated with depressive symptoms or growth, including maternal education, poverty status, infant sex, birth order, receipt of zinc or iron supplements, Home Inventory score, maternal perception of infant temperament, and months breastfed. To test the second hypothesis, that the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth varies by maternal perception of infant temperament, we reran the regression analysis including the interaction between depressive symptoms and maternal perception of infant temperament. To test the final hypothesis, that the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth is mediated by the home environment, we conducted a stepwise regression analysis to examine whether the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth was attenuated by the introduction of the Home Inventory score into the model (29).

RESULTS

At enrollment the mean (± SD) maternal age was 28.1 ± 5.8 y. Most mothers were married (98.2%), and 48.6% had <5 y of schooling. The mean household size was 6.4, and 72.5% of the children had older siblings. Eighteen percent of the infants were stunted (length-for-age <−2 z scores), and more than two-thirds (68%) were mildly anemic (hemoglobin < 110.0 g/L).

There were no differences in the infants' length-for-age or weight-for length at 6 mo based on their mothers' depression status at 12 mo (Table 1). The infants' relative position on both indexes worsened significantly over time. At 12 mo, there was a significant depression-by-time effect on length-for-age, which indicated worse growth for infants of mothers with depressive symptoms (Table 1). By 12 mo, 36.9% of the infants were stunted. Infants of mothers with depressive symptoms had a 2.17 higher odds of being stunted (95% CI: 1.24, 3.81; P = 0.007) than did infants of mothers with few symptoms (45.3% compared with 27.6%).

The correlation matrix showed that maternal depressive symptoms were significantly related to length-for-age at 12 mo (r = −0.13, P = 0.05), but not to other anthropometric indexes at 6 or 12 mo (Table 2). Both depressive symptoms and length-for-age at 12 mo were related to the Home Inventory score, infant temperament, maternal education, and poverty—all in the expected direction, which indicated better growth for infants in stimulating homes, with easygoing temperaments, with better-educated mothers, and with lower rates of poverty. There were no differences in breastfeeding duration or mother-reported birth size by depressive symptoms. Weight-for-length at 12 mo was positively related to infant temperament, maternal education, and poverty, but not to the Home Inventory score.

The first hypothesis, that maternal depressive symptoms are associated with poor infant growth, was supported for change in length-for-age from 6 to 12 mo. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusting for 6-mo length-for-age, maternal depressive symptoms predicted 12-mo length-for-age (Table 3, model 1). The association remained significant after the covariates were introduced (Table 3, model 3). Maternal education was the only covariate that was a significant predictor of 12-mo length-for-age.

TABLE 3.

Multiple regression analysis of effects of maternal depressive symptoms, Home Inventory score, and infant temperament on 12-mo length-for-age and weight-for-length1

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||||

| B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | |

| Length-for-age at 12 mo | |||||||||

| Length-for-age at 6 mo | 0.89 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Maternal depressive symptoms | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.006 | −0.007 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.007 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Home Inventory score | 0.01 | 0.01 | NS | 0.01 | 0.01 | NS | |||

| Infant temperament | 0.13 | 0.10 | NS | ||||||

| R2 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Weight-for-length at 12-mo | |||||||||

| Weight-for-length at 6 mo | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.001 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 0.001 |

| Maternal depressive symptoms | −0.01 | 0.03 | NS | −0.01 | 0.01 | NS | −0.01 | 0.01 | NS |

| Home Inventory score | 0.01 | 0.01 | NS | −0.01 | 0.01 | NS | |||

| Infant temperament | 0.25 | 0.14 | NS | ||||||

| R2 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.32 | ||||||

n = 221. Adjusted for maternal education, infant sex, birth order, receipt of iron and zinc, and months breastfed.

The first hypothesis was not supported for weight-for-length. In a multivariate regression analysis that adjusted for 6-mo weight-for-length, maternal depressive symptoms did not predict 12-mo weight-for-length (Table 3). When the covariates were introduced, there were no significant predictors beyond weight-for-length at 6 mo.

The second hypothesis, that the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth is moderated by perceptions of infant temperament, was not supported. The interaction of depression by infant temperament did not account for significant variance in the prediction of either length-for-age or weight-for-length at 12 mo.

The third hypothesis, that the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth is mediated by the home environment, was partially supported. The first 2 criteria for mediation were met (30): 1) the home environment was related to both maternal depressive symptoms and to 12-mo length-for-age and 2) when the home environment was included in the model, the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth was attenuated. However, after introduction of the covariates into the model, particularly maternal education, the home environment was not a significant predictor of 12-mo length-for-age.

DISCUSSION

Children of mothers with depressive symptoms experienced poor linear growth from 6 to 12 mo of age. At 6 mo, there were no differences in infant weight or length related to maternal depressive symptoms. However, from 6 to 12 mo, infants of mothers with depressive symptoms experienced linear growth faltering severely or chronically enough to cause stunting. By 12 mo, almost one-half the infants (45%) of mothers with depressive symptoms were stunted, as opposed to just more than one-quarter (27%) of the infants of mothers with few depressive symptoms.

By 12 mo, infants are typically consuming the family diet and learning to self-feed, but they require substantial feeding assistance. They are inquisitive and mobile as they are learning to walk and talk. Caregiving demands at this age may be particularly difficult for mothers burdened by depressive symptoms. The symptoms that characterize maternal depression, including sadness, negative affect, loss of interest in daily activities, fatigue, difficulty thinking clearly, and bouts of withdrawal and intrusiveness may interfere with consistent and responsive caregiving (19). Even basic caregiving tasks may be overlooked (31, 32), potentially contributing to inconsistent caregiving related to feeding and the risk of problems in children's growth and health (33).

Maternal perceptions of infant temperament

The relation between depressive symptoms and infants' growth was not moderated by maternal reports of infant irritability. Perceptions of infant irritability were associated with 12-mo length-for-age and weight-for-length, favoring infants perceived to be easygoing. Infant temperament was negatively associated with depressive symptoms and positively associated with maternal education. In other words, mothers with depressive symptoms tended to view their infants as temperamentally difficult, and better-educated mothers viewed their infants as easygoing.

Although irritability was not related to breastfeeding duration, other investigators have reported associations between infant irritability and both shortened duration of breastfeeding and feeding problems (16, 34). In contrast with our findings, investigators in high-income countries have found that irritable infants are heavier than easygoing infants (35, 36); caregivers may provide more food either because they interpret irritability as hunger or to placate irritability. Thus, maternal perceptions of infant temperament may influence feeding behavior and should be considered in subsequent investigations of infant growth and development.

Home environment

The association between maternal depressive symptomatology and low Home Inventory scores suggests that infants of mothers with depressive symptoms also experienced a home environment with limited stimulation. Across cultures, infants with few opportunities for exploration and social engagement at home are at risk of delays in the acquisition of developmental skills (28). The slow linear growth and high rates of stunting among infants of mothers with depressive symptoms are of concern because they suggest that infants are not receiving either the nutrients or caregiving that they need to grow and develop. Poor growth early in life places children at risk of academic and behavioral problems during their school-age years (7, 8).

Environmental context and food insecurity

In low-income countries, such as Bangladesh, growth faltering begins early in life (37). On the basis of the World Health Organization Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition, which includes 39 nationally representative datasets from low-income countries, length starts to falter shortly after birth and weights start to falter at ≈3 mo of age (38). Both indexes continue to decline, especially in the first year of life. Infants may be particularly vulnerable to maternal depressive symptoms early in life, when both their dependency and nutritional needs are high.

Depressive symptoms were relatively common among rural Bangladeshi mothers of infants. Consistent with previous reports (39–44), mothers with depressive symptoms were the most impoverished in the sample and had multiple environmental risks, including low income and low education levels.

In low-income societies, such as Bangladesh, food insecurity, defined as limited or uncertain availability of enough food for an active and healthy life (45), is high (46, 47). The US Agency for International Development estimates that approximately one-half of Bangladesh's 140 million inhabitants are below the poverty line and are food-insecure (48). Food insecurity can interfere with feeding practices. For example, one study found that food-secure families in Bangladesh were more likely to provide age-appropriate feeding practices (eg, provide semisolid foods) in the second 6 mo of life than were less food-secure families (49).

In addition to inadequate food, food insecurity has been associated with depressive symptoms in low-income countries such as Tanzania and Ethiopia (50, 51) and in high-income countries such as the United States (52, 53). The situational aspects of the relation between food insecurity and depression were shown in a recent study in which seasonal changes in food insecurity predicted corresponding changes in symptoms of maternal anxiety and depression (51). Seasonal variation in the availability of food is common (46). Indeed, in Bangladesh, rates of low birth weight are highest during seasons when food supplies are limited (55). Thus, maternal depressive symptoms may at least partially reflect the instability that occurs when families do not have enough food to feed their children (51).

Methodologic considerations

Several methodologic issues should be considered when interpreting these data. First, our interpretation suggests that mothers with depressive symptoms at 12 mo experienced mood disorders earlier in their parenting (4). Although data from India (39, 42) and Pakistan (56) have shown stability of maternal depressive symptoms during early parenting, we have no evidence regarding the stability of depressive symptoms among mothers in Bangladesh. Second, although the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and linear growth was significant, the effects were small, which suggests that multiple factors influence early growth. We adjusted for multiple personal and environmental factors, but we did not control for possible differences in maternal health, nutritional status, or life events—factors known to affect mother-child interactions (57) and possibly early growth. Finally, the time sequence of the measurements limited our ability to draw inferences beyond associations. It is plausible that mothers may have reacted to their infants' poor linear growth with symptoms of depression.

Implications for programs and policy

The relatively high prevalence of depressive symptoms among women in Bangladesh and the poor growth among their infants indicates that the global burden of disease associated with maternal depressive disorders extends to the next generation. These data contribute to the evidence that the association between maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth occurs in the context of extreme poverty (58), probably exacerbated by food insecurity (51).

Evidence from the current study in combination with other data linking symptoms of maternal depressive disorders with infant growth and development suggest that a multilevel approach is needed to ensure the health and well-being of infants in low-income countries (1, 59). Families need consistent access to adequate food, thereby reducing the anxiety and depression associated with food insecurity. Women need education, opportunities, and support for their roles as society members and mothers, including screening and treatment of depressive disorders. Infants and young children need integrated programs that include nutrition and early child development. Although successful interventions exist at each level (1, 59), investments have been slow and few integrated programs exist. However, the evidence from existing intervention trials designed to promote early mother-child interaction is encouraging and may serve as a model for interrupting the intergenerational consequences associated with maternal depressive disorders (59). (Other articles in this supplement to the Journal include references 60–65.)

Acknowledgments

The authors' responsibilities were as follows—MMB: analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; AHB: secured the funds, oversaw the entire study, and contributed to the design; KZ and SEA: supervised the data collection; and REB: assisted in securing the funds and contributed to the design. All authors made contributions to the manuscript and approved the final draft. None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahman A, Patel V, Maselko J, Kirkwood B. The neglected ‘m’ in MCH programmes—why mental health of mothers is important for child nutrition. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:579–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007;370:859–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Mental health: new understanding new hope. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA. Intergenerational transmission of depression: test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:511–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray L, Fiori Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper P. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Dev 1996;67:2512–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissman MM, Wickramaraine P, Nomura Y, et al. Families at high and low risk for depression: a 3-generation study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkman DS, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, Lopez SL, Black MM. Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet 2002;359:564–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez MA, Adair LS. Severity and timing of stunting in the first two years of life affect performance on cognitive tests in late childhood. J Nutr 1999;129:1555–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anoop S, Saravanan B, Joseph A, Cherian A, Jacob K. Maternal depression and low maternal intelligence as risk factors for malnutrition in children: a community based case-control study from South India. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:325–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harpham T, Huttly S, De Silva MJ, Abramsky T. Maternal mental health and child nutrition status in four developing countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:1060–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, DeSouza N, Rodrigues M. Postnatal depression and infant growth and development in low-income countries: a cohort study from Goa, India. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:34–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Bunn J, Lovel H, Harrington R. Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:946–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahman A, Lovel H, Bunn J, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Mothers' mental health and infant growth: a case-control study from Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Child Care Health Dev 2004;30:21–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Miranda CT, Turecki G, Mari Jde J, et al. Mental health of the mothers of malnourished children. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:128–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surkan P, Kawachi I, Ryan LM, Berkman LF, Carvalho VL, Peterson KE. Maternal depressive symptoms, parenting self-efficacy, and child growth. Am J Public Health 2008;98:125–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adewuya AO, Ola BO, Aloba OO, Mapayi BM, Okeniyi JAO. Impact of postnatal depression on infants' growth in Nigeria. J Affect Disord 2008;108:191–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomlinson M, Cooper PJ, Stein A, Swartz L, Molteno C. Post-partum depression and infant growth in a South African peri-urban settlement. Child Care Health Dev 2006;32:81–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker Henningham H, Powell C, Walker S, Grantham McGregor S. Mothers of undernourished Jamaican children have poorer psychosocial functioning and this is associated with stimulation provided in the home. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:786–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black MM, Baqui AH, Zaman K, et al. Depressive symptoms among rural Bangladeshi mothers: implications for infant development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007;48:764–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baqui AH, Zaman K, Persson LA, et al. Simultaneous weekly supplementation of iron and zinc is associated with lower morbidity due to diarrhea and acute lower respiratory infection in Bangladeshi infants. J Nutr 2003;133:4150–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black MM, Baqui AH, Zaman K, et al. Iron and zinc supplementation promote motor development and exploratory behavior among Bangladeshi infants. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:903–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization, Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group WHO Child Growth Standards: methods and development: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/technical_report/en/index.html (cited 8 June 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caldwell B, Bradley R. Home observation for measurement of the environment. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates JF, Friedland CA, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Dev 1979;50:794–803 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldsmith HH. Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Dev 1996;67:218–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black MM, Sazawal S, Black RE, Khosla S, Kumar J, Menon V. Cognitive and motor development among small-for-gestational-age infants: impact of zinc supplementation, birth weight, and caregiving practices. Pediatrics 2004;113:1297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley R, Corwyn R, Whiteside Mansell L. Life at home: same time, different places—an examination of the HOME Inventory in different cultures. Early Dev Parenting 1996;5:251–69 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlational analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leiferman J. The effect of maternal depressive symptomatology on maternal behaviors associated with child health. Health Educ Behav 2002;29:596–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLennan JD, Kotelchuk M. Parental prevention practices for young children in the context of maternal depression. Pediatrics 2000;105:1090–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman A, Bunn J, Lovel H, Creed F. Maternal depression increases infant risk of diarrhoeal illness: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:24–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galler JR, Harrison R, Ramsey F, Chawla S, Taylor J. Postpartum feeding attitudes, maternal depression, and breastfeeding in Barbados. Infant Behav Dev 2006;29:189–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carey WB. Temperament and increased weight gain in infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1985;6:128–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells J, Stanley M, Laidlaw A, Day J, Stafford M, Davies P. Investigation of the relationship between infant temperament and later body composition. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997;21:200–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saha KK, Frongillo EA, Alam DS, Arifeen SE, Persson LA, Rasmussen KM. Appropriate infant feeding practices result in better growth of infants and young children in rural Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1852–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shrimpton R, Victora CG, de Onis M, Lima RC, Blossner M, Clugston S. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: implications for nutritional interventions. Pediatrics 2001;107:E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India. Incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colla J, Buka S, Harrington D, Murphy JM. Depression and modernization: a cross-cultural study of women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 2006;41:271–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Husain N, Creed F, Tomenson B. Depression and social stress in Pakistan. Psychol Med 2000;30:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:43–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichenheim ME, Harpham T. Maternal mental health in a squatter settlement in Rio de Janeiro. Br J Psychiatry 1991;159:683–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolf A, De Andraca I, Lozoff B. Maternal depression in three Latin American samples. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 2002;37:169–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nord M, Hopwood H. Recent advances provide improved tools for measuring children's food security. J Nutr 2007;137:533–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.FAO The state of food insecurity in the world. Rome, Italy: FAO, United Nations, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Agency for International Development Concurrent conditions: food security. Dhaka (Bangladesh). Available from: http://www.usaid.gov/bd/programs/food_sec.html (cited November 2008)

- 48.Faisal IM, Parveen S. Food security in the face of climate change, population growth, and resource constraints: implications for Bangladesh. Environ Manage 2004;34:487–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saha KK, Frongillo EA, Alam DS, Arifeen SE, Persson LA, Rasmussen KM. Husehold food security is associated with infant feeding practices in rural Bangladesh. J Nutr 2008;138:1383–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadley C, Paril CL. Food insecurity in rural Tanzania is associated with maternal anxiety and depression. Am J Hum Biol 2006;18:359–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hadley C, Patil CL. Seasonal changes in household food insecurity and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Am J Phys Anthropol 2008;135:225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casey P, Goolsby S, Berkowitz , et al. Maternal depression, changing public assistance, food security, and child health status. Pediatrics 2004;113:298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitaker RC, Philips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics 2006;118:e859–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaslow M, Bronte-Tinkew J, Capps A, Horowitz A, Moore KA, Weinstein D. Food security during infancy: implications for attachment and mental proficiency in toddlerhood. Matern Child Health J 2009;13:66–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hort KP. Seasonal variation of birthweight in Bangladesh. Ann Trop Paediatr 1987;7:66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rahman A, Creed F. Outcome of prenatal depression and risk factors associated with persistence in the first postnatal year: prospective study from Rawalpindi, Pakistan. J Affect Disord 2007;100:115–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez EM, Hendricks MK, Beard JL, et al. Mother-infant interactions and infant development are altered by maternal iron deficiency anemia. J Nutr 2005;135:850–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stewart RC. Maternal depression and infant growth: a review of recent evidence. Matern Child Nutr 2007;3:94–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman J, et al. Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet 2007;369:229–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Black MM, Ramakrishnan U. Introduction. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):933S–4S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wachs TD. Models linking nutritional deficiencies to maternal and child mental health. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):935S–9S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DiGirolamo AM, Ramirez-Zea M. Role of zinc in maternal and child mental health. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):940S–5S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Iron deficiency and child and maternal health. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):946S–50S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramakrishnan U, Imhoff-Kunsch B, DiGirolamo AM. Role of docosahexaenoic acid in maternal and child mental health. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):958S–62S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Engle PL. Maternal mental health: program and policy implications. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):963S–6S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]