Abstract

Oxidized and/or glycated LDL may mediate capillary injury in diabetic retinopathy. The mechanisms may involve pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant effects on retinal capillary pericytes. In this study, these effects, and the protective effects of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), were defined in a primary human pericyte model. Human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml of native LDL (N-LDL) or heavily oxidized glycated LDL (HOG-LDL) with or without PEDF at 10–160 nM for 24 h. To assess pro-inflammatory effects, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) secretion was measured by ELISA, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation was detected by immunocytochemistry. Oxidative stress was determined by measuring intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), peroxynitrite (ONOO−) formation, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and nitric oxide (NO) production. The results showed that MCP-1 was significantly increased by HOG-LDL, and the effect was attenuated by PEDF in a dose-dependent manner. PEDF also attenuated the HOG-LDL-induced NF-κB activation, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of PEDF on MCP-1 was at least partially through the blockade of NF-κB activation. Further studies demonstrated that HOG-LDL, but not N-LDL, significantly increased ONOO− formation, NO production, and iNOS expression. These changes were also alleviated by PEDF. Moreover, PEDF significantly ameliorated HOG-LDL-induced ROS generation through up-regulation of SOD1 expression. Taken together, these results demonstrate pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant effects of HOG-LDL on retinal pericytes, which were effectively ameliorated by PEDF. Suppressing MCP-1 production and thus inhibiting macrophage recruitment may represent a new mechanism for the salutary effect of PEDF in diabetic retinopathy and warrants more studies in future.

Keywords: PEDF, oxidized LDL, inflammation, oxidative stress

Diabetic retinopathy is a common microvascular complication of diabetes and the most frequent cause of vision loss in diabetic patients (Fong, et al. 2003). In recent years, accumulating evidence suggests that inflammation is a key event in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications (Abu El-Asrar, et al. 1997; Hernández, et al. 2005; Mitamura, et al. 2001). In early stages of diabetic retinopathy, expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and chemokines is significantly up-regulated in retina, in parallel with breakdown of blood-retina barrier and increased vascular permeability (Joussen, et al. 2004; Zhang, et al. 2006). Moreover, enhanced chemokine secretion into the retina and vitreous triggers recruitment and accumulation of monocyte/macrophage from blood to retina, contributing significantly to endothelial cell damage, capillary occlusion, non-perfusion, and neovascularization in the retina in diabetic retinopathy (Schröder, et al. 1991; Tashimo, et al. 2004).

Monocyte chemoattractant factor-1 (MCP-1) is a 14 kDa glycoprotein, commonly expressed in all vascular cells involved in inflammatory process (Hernández et al. 2005). MCP-1 belongs to the CC chemokine family and is a potent chemoattractant for monocytes. The critical role of MCP-1 in diabetic vascular complications has been intensively studied and established in cardiovascular (macrovascular) diseases in diabetes (Renier, et al. 2003; Sonoki, et al. 2002). In diabetic retinopathy, MCP-1 levels in the vitreous are significantly elevated in the patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (Abu El-Asrar et al. 1997; Hernández et al. 2005; Mitamura et al. 2001). In streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic animals, expression of MCP-1 is also up-regulated in retina, and correlates with increased retinal vascular permeability (Zhang et al. 2006). In oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy, a commonly accepted model for proliferative diabetic retinopathy, mRNA and protein levels of MCP-1 are increased in hypoxic inner retina at 3 h and 12 h, respectively after ischemia(Yoshida, et al. 2003). Moreover, administration of neutralizing antibodies against MCP-1 effectively reduced abnormal new vessel growth in the retina, suggesting a role of MCP-1 and monocyte/macrophage recruitment in retinal neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy (Davies, et al. 2006; Yoshida et al. 2003).

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is a major endogenous angiogenic inhibitor in the retina (Dawson, et al. 1999). Decreased PEDF levels in the retina have been shown to be implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic macular edema and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (Gao, et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2006). Previously we reported that PEDF is a potent anti-inflammatory factor, inhibiting expression of pro-inflammatory factors, i.e. vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), in retinal vascular endothelial cells (Zhang et al. 2006). Administration of PEDF into the vitreous significantly reduces retinal vascular leakage in diabetic animals(Zhang et al. 2006). Recent studies demonstrate that PEDF inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage activation and induces macrophage apoptosis, suggesting a potential role of PEDF in ameliorating macrophage-implicated inflammatory events in diabetic retinopathy (Ho, et al. 2008; Zamiri, et al. 2006).

Oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL)-mediated inflammation and vascular damage is recognized as central to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and to the accelerated atherosclerosis of diabetes (Renier et al. 2003; Sonoki et al. 2002). An important mechanism for the deleterious effect of oxidized LDL on vascular function is to induce MCP-1 production and monocyte/macrophage recruitment (Renier et al. 2003; Sonoki et al. 2002). In diabetic retina, the disrupted blood-retinal barrier and increased vascular permeability result in extravasation and accumulation of LDL in the perivascular space, where it undergoes additional glycation and extensive oxidation. In a recent immunohistochemistry study, we demonstrated the presence of apoB (the apolipoprotein of LDL) and of oxidized LDL in human retina from diabetic subjects in amounts increasing with the severity of diabetic retinopathy (Wu et al. 2008). In contrast, neither apoB nor oxidized LDL was detectable in normal retina. Our previous studies demonstrate that “heavily oxidized, glycated LDL” (HOG-LDL; i.e. normal, pooled human LDL that has been modified in vitro first by glycation, then by oxidation to simulate conditions present in diabetes) induces apoptosis in retinal pericytes (Lyons, et al. 2000). Moreover, HOG-LDL decreases the expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 (TIMP3) in retinal perictyes (Barth, et al. 2007). Here we hypothesize that HOG-LDL is a potent inducer of MCP-1 generation and oxidative stress in the retina, and that PEDF, an endogenous anti-inflammatory factor, suppresses HOG-LDL-induced MCP-1 production and thus inhibits monocyte/macrophage recruitment in diabetic retina. In the present study, we studied the effect of PEDF on HOG-LDL-induced MCP-1 production in retinal pericytes and explored the underlying mechanisms on nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway and oxidative stress.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagles Medium (DMEM with 5 mmol/L D-glucose), hydrocortisone, human fibroblast growth factor B (hFGF-B), VEGF, R3-IGF-1, ascorbic acid, human epidermal growth factor (hEGF) and gentamicin sulphate and amphotericin-B (GA-1000) were purchased from Clonetics, Inc.(Walkersville, MD). Fetal bovine serum and antibiotic/mycotic solution were purchased from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). Native LDL (N-LDL) was isolated from human plasma, and heavily oxidized glycated LDL (HOG-LDL) was prepared from native LDL (N-LDL); both were characterized as described previously (Song, et al. 2005). Human MCP-1 ELISA kit was purchased from Chemicon Inc. (Temecula, CA). NF-κB activation assay kit was purchased from Cellomics Inc., (Pittsburgh, PA). 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) and Greiss reaction kit were purchased from Molecular Probe, Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-3-Nitrotyrosine (3-NT) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Anti-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from ABcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA).

Cell culture

Primary human retinal pericytes were purchased from Clonetics, Inc. (Walkersville, MD). The cells were grown in medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.04% hydrocortisone, 0.4% hFGF-B, 0.1% VEGF, 0.1% R3-IGF-1, 0.1% ascorbic acid, 0.1% hEGF and 0.1% GA-1000 at 37°C in a 5% CO2, 95% air incubator. After reaching 85% of confluence, cells were treated in low-serum medium (containing 0.5% serum) for 24 h to obtain quiescence, and then exposed to desired treatment in triplicate. Cells in passages 3–6 were used for experiments.

Western blot analysis of 3-NT, iNOS, and SOD1 in pericytes

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Zhang, et al. 2004). Briefly, the cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing 50mM Tris-cl pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 1mM PMSF, protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor. Protein concentration was measured with the BioRad DC protein assay kit. Fifty µg of protein from total cell lysate was separately blotted with anti-3-NT (1:1000), anti-iNOS (1:1000), and anti-SOD1 (1:2000). The same membrane was stripped and reblotted with an anti-β-actin antibody (1:4000) as control.

Quantification of MCP-1 secretion in pericytes

MCP-1 secreted into the medium was determined using a sandwich enzyme immunoassay (EIA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the cell culture supernatant was collected after treatment and centrifuged to remove any visible particulate material. Standards or sample (100 µl) were added to the antibody pre-coated microtiter plate. Simultaneously 25 µl of rabbit anti-Human MCP-1 polyclonal antibody was dispensed into each well. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 3 h. After four washings, 50 µL of Goat anti-Rabbit conjugated alkaline phosphatase was added, followed by incubation for 45 min. Then substrate was added and incubated for 5 minutes, the plate was read immediately at 490 nm in a Victor microplate reader. The MCP-1 concentration was calculated according to the standard curve and normalized by cell numbers.

NF-κB activation assay

NF-κB activation was evaluated by an NF-κB activation assay kit based on immunofluorescein method. Briefly, cultured pericytes were seeded and grown to 80% confluence on 4-chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International Corp., Naperville, IL). After quiescence for 24h, the cells were treated with N-LDL or HOG-LDL at 100 µg/ml, in the presence or absence of PEDF for 24 hr. After fixation with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilization for 3 min, the cells were incubated with primary and secondary antibody for 1 h. The nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst dye. After extensive washing, the slides were visualized and photographed under a fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany).

Detection of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation

The cells were seeded in 96-well plate and grown to 85% confluence. After quiescence for 24 h, the cells were exposed to 100 µg/ml of N-LDL or HOG-LDL with or without PEDF for 24 h. The generation of intracellular ROS was detected by dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) method using carboxy-H2DCFDA, a cell-permeable indicator for ROS (Obrosova, et al. 2005). Briefly, the cells were gently washed with PBS and incubated with 2 µM carboxy-H2DCFDA in phenol red-free medium at 37 °C for 20 min. The medium was discarded and cells were washed with PBS. Fluorescence was measured by a fluorescence microplate reader with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 538 nm.

Measurement of nitric oxide (NO) production in pericytes

NO production was evaluated by measuring the accumulation of nitrites, a stable oxidative end product of NO metabolism, in the supernatant of cultured pericytes using the Greiss reagent kit following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the samples were incubated with 100 mIU/ml nitrate reductase and 20 µg/ml NADPH to convert nitrates to nitrites for analysis. Then 150 µl of sample was added to 20 µl of premixed Greiss reagent (containing sulphanilamide and N-[1-naphtyl]ethylendiamine) and 130 µl of deionized water in a 96-well microplate and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The optical density was measured with a Victor microplate reader at a wavelength of 546 nm. Nitrite concentrations in the supernatants were calculated according to the standard curve.

Statistical analysis

Data were calculated and expressed as group means±SD. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test, ANOVA, and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Statistical differences were considered significant at a P value of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

HOG-LDL induces MCP-1 secretion in retinal pericytes, and PEDF inhibits this effect

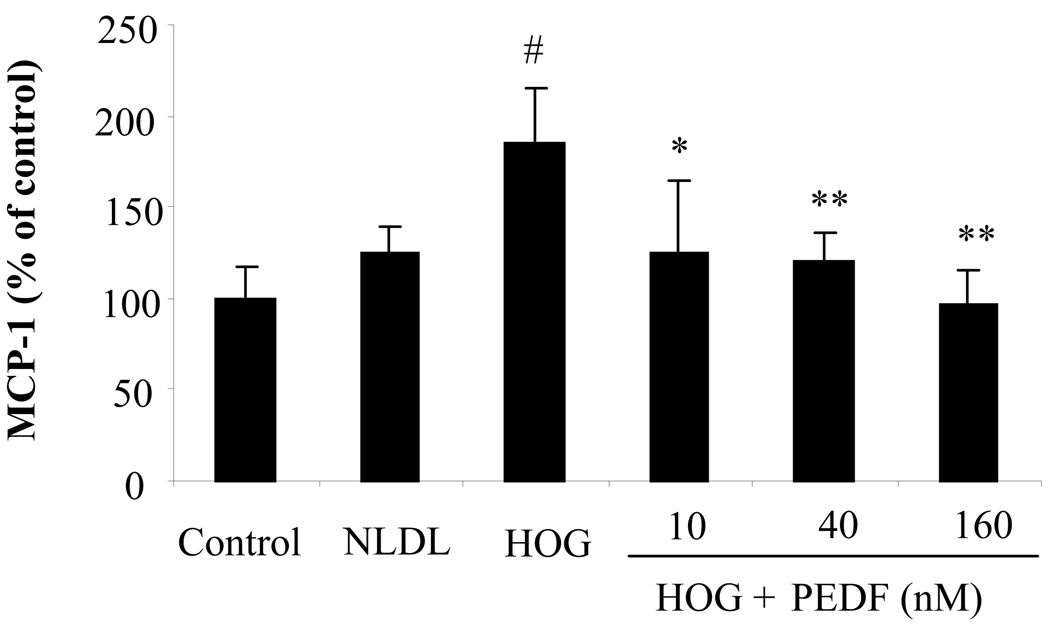

Oxidized LDL is a major inducer of MCP-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells, and plays a central role in diabetic macrovascular complications (Mamputu and Renier 2001). However, the effect of oxidized LDL on diabetic retinopathy is under-investigated. In the present study, we determined MCP-1 secretion induced by HOG-LDL in retinal pericytes. Cultured primary human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml of N-LDL or 100 µg/ml HOG-LDL for 24 h. MCP-1 secreted into the medium was measured by ELISA. The results showed that MCP-1 secretion from the pericytes exposed to HOG-LDL was significantly elevated when compared to those exposed to N-LDL or normal control (Fig. 1, p<0.01, ANOVA). No significant difference was observed in MCP-1 levels between the cells exposed to N-LDL and normal controls.

Figure 1. Blockade of oxidized LDL-induced MCP-1 secretion by PEDF in retinal pericytes.

Cultured human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml of N-LDL or 100 ug/ml HOG-LDL with or without different concentrations of PEDF at 10, 40, and 160 nM for 24 h. MCP-1 secreted into the medium was measured by ELISA (mean±SD, n=3). The values statistically different from untreated control and that treated with N-LDL are indicated by # P<0.05, from HOG-LDL as *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

To determine the effect of PEDF on oxidized LDL-induced MCP-1 production in retinal pericytes, we exposed cultured retinal pericytes to 100 µg/ml HOG-LDL with or without PEDF at 10, 40 and 160 nM for 24 h. MCP-1 level was measured in the medium. The results showed that PEDF significantly decreased MCP-1 production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1, P<0.05, ANOVA).

NF-κB activation in retinal pericytes was induced by oxidized LDL, and the effect was inhibited by PEDF

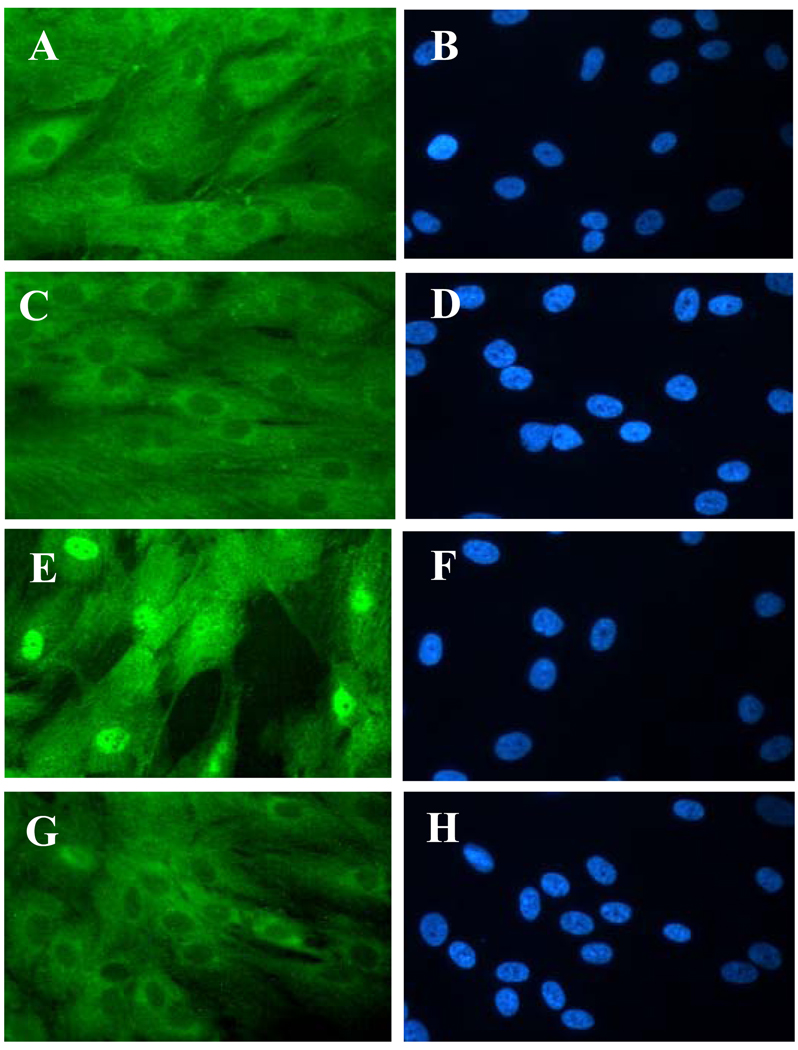

NF-κB activation is an important transcriptional factor regulating the expression of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, including MCP-1(Renier et al. 2003; Sonoki et al. 2002). Moreover, previous studies suggest that NF-κB activation is an essential step in the over-production of MCP-1 induced by oxidized LDL or glycated and oxidized LDL in vascular cells (Renier et al. 2003; Sonoki et al. 2002). Thus, we next determined if PEDF reduces HOG-LDL-induced MCP-1 secretion through the inhibition of NF-κB activation. Cultured human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml N-LDL or HOG-LDL in the presence or absence of 160 nM PEDF for 24 h. NF-κB activation was analyzed by the translocation of NF-κB from cytoplasm to nuclei using immunocytochemistry. The results showed that the signal of NF-κB was diffusely distributed in cytoplasm in control cells (Fig. 2A, 2B). After incubation with HOG-LDL (Fig. 2E, 2F) but not N-LDL (Fig. 2C, 2D) for 24 h, NF-κB translocated from cytoplasm to nuclei (Fig. 2C–2F), indicating that NF-κB was activated by HOG-LDL. The nuclear translocation of NF-κB was almost completely blocked by PEDF (Fig. 2G, 2H). These results indicated that the effect of PEDF on reducing MCP-1 production was at least partially through inhibition of NF-κB activation.

Figure 2. Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation by PEDF in retinal pericytes.

Cultured human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml N-LDL or HOG-LDL in the presence or absence of 160 nM PEDF for 24 h. The cells were fixed and stained by an anti-NF-κB antibody and visualized under a fluorescent microscope. Magnification: 400×. A, C, E, G: NF-κB staining; B, D, F, H: DAPI staining for visualizing of nuclei. The results showed that the signal of NF-κB was diffusely distributed in cytoplasm in untreated control cells (A), and translocated from cytoplasm to nuclei in the cells exposed to HOG-LDL (E), but not in those treated with N-LDL (C). PEDF at 160 nM effectively blocked HOG-LDL-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation (G).

HOG-LDL induced peroxynitrite formation in retinal pericytes; PEDF inhibits this effect

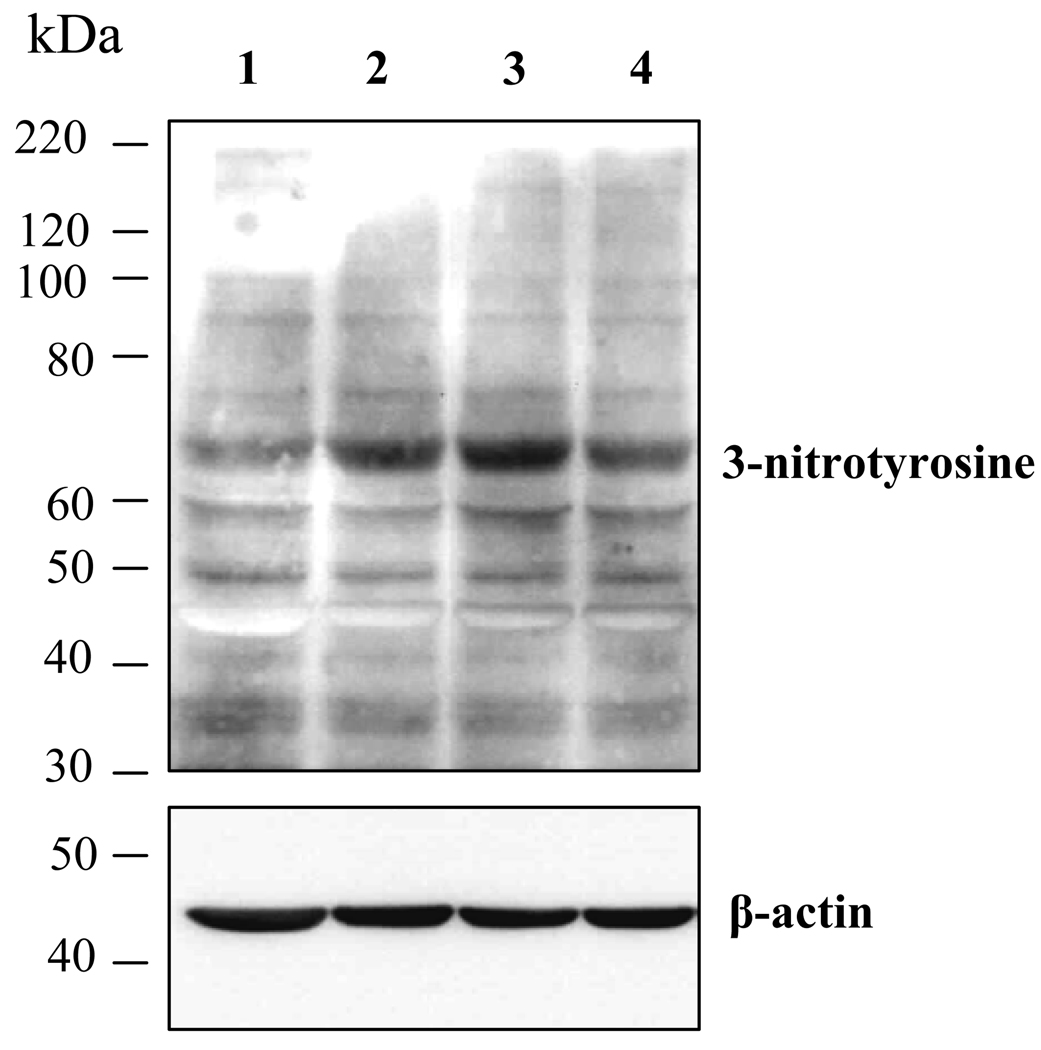

Oxidative stress has been recognized as a critical mediator for inflammation and NF-κB activation induced by oxidized LDL (Renier et al. 2003). Peroxynitrite (ONOO−) is a potent oxidant, which initiates both nitrosative and oxidative reactions affecting cellular proteins, lipids and DNA, and resulting in an increase of oxidative stress and a decrease of antioxidant defenses (Zou, et al. 2002). Scavenging of ONOO− effectively diminishes diabetes-induced retinal vascular leakage, suggesting a crucial role of ONOO− in diabetic retinopathy (El-Remessy, et al. 2003). We hypothesize that PEDF inhibits HOG-LDL-induced NF-κB activation via suppressing oxidant generation in retinal pericytes. To test this hypothesis, we determined the formation of peroxynitrite in cultured retinal pericytes exposed to HOG-LDL in the presence or absence of PEDF. Peroxynitrite was detected by western blot analysis of 3-nitronyrosine (3-NT)-positive proteins, which has been commonly accepted as a “footprint” of ONOO− in cell culture (Obrosova et al. 2005; Zou et al. 2002). The results showed that 100 µg/ml HOG-LDL induced an increase of 3-NT levels (Fig. 3). N-LDL at the same concentration did not increase 3-NT formation. The addition of PEDF (160 nM) partially inhibit HOG-LDL-induced 3-NT formation, but did not restore control levels (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Peroxynitrite formation in retinal pericytes exposed to oxidized-LDL.

Cultured human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml N-LDL or HOG-LDL in the presence or absence of 160nM PEDF for 24 h. Peroxynitrite levels were determined by 3-nitronyrosine (3-NT)-positive proteins in the whole cell lysate measured by western blot analysis. The same membrane was stripped and reblotted with an anti-β-actin antibody. Lane 1: untreated control cells; Lane 2: 100 µg/ml N-LDL; Lane 3: 100 µg/ml HOG-LDL; Lane 4: 100 µg/ml HOG-LDL + 160 nM PEDF.

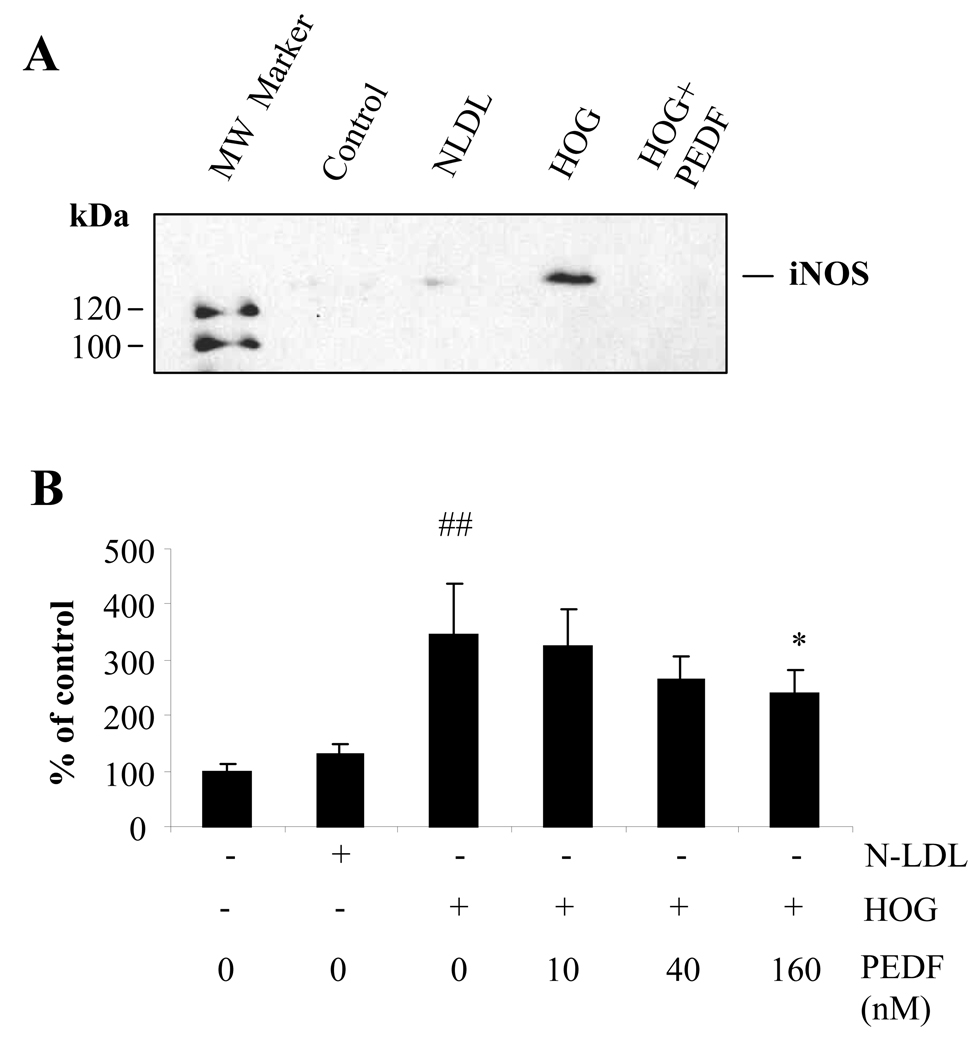

HOG-LDL induced iNOS expression and NO production in retinal pericytes, and effects were blocked by PEDF

ONOO− is formed via the reaction of O2.− with NO (Zou et al. 2002). The over-production of NO not only provides an essential precursor for ONOO− generation, but also contributes to pericyte loss in diabetic retinopathy (Miller, et al. 2006). In this study, we determine the effects of HOG-LDL on NO production and iNOS expression in retinal pericytes in the presence and absence of PEDF. The results showed that the levels of iNOS expression (Fig. 4A) and NO production (Fig. 4B) were very low in control cells. HOG-LDL, but not N-LDL, significantly increased iNOS expression and correspondent NO production, which were significantly reduced by 160 nM PEDF (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Inhibitory effect of PEDF on oxidized LDL-induced iNOS expression and NO production in retinal pericytes.

Cultured human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml N-LDL or HOG-LDL without or with PEDF at 10, 40, 160 nM for 24 h. Expression of iNOS in pericytes exposed to HOG-LDL without or with PEDF (160 nM) was determined by western blot analysis (A). NO production was measured by Griess reaction and expressed as percentage of control (B). The values statistically different from untreated control and N-LDL are indicated by ## P<0.01, from HOG-LDL as *P<0.05.

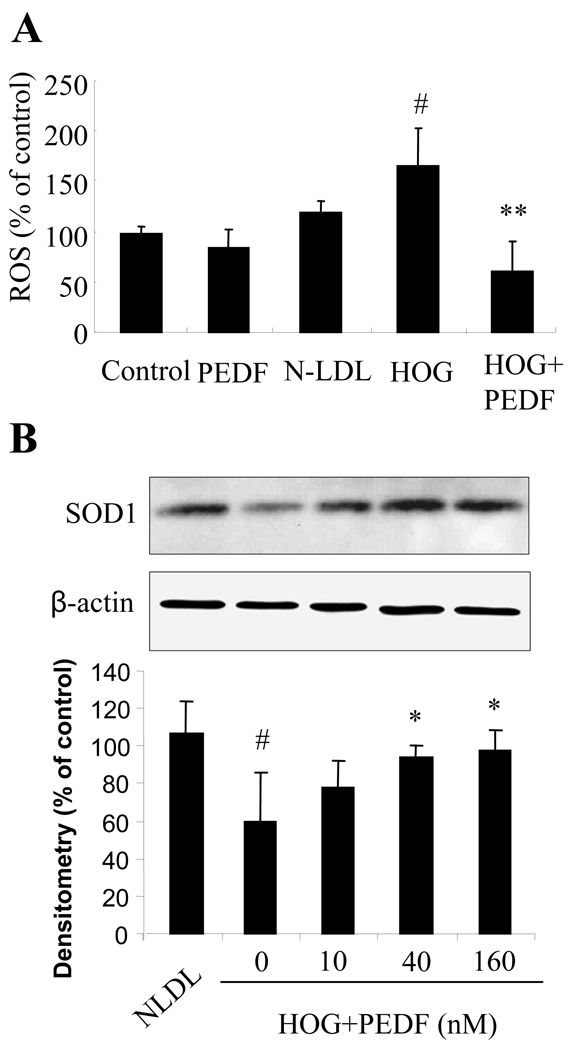

PEDF reduced ROS production through up-regulation of SOD1 expression in retinal pericytes

We determined if HOG-LDL induced ROS generation in pericytes, and the effects of PEDF. Cultured retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml HOG-LDL or N-LDL in the presence or absence of PEDF at 160 nM for 24 hrs, and intracellular ROS generation was measured. The results showed that HOG-LDL significantly increased, and the addition of PEDF significantly decreased, ROS generation (Fig. 5A). To further elucidate how PEDF inhibits ROS generation, we determined the effect of PEDF on expression of SOD1 in retinal pericytes exposed to HOG-LDL in the presence or absence of PEDF at 10, 40 and 160 nM. The results showed that HOG-LDL treatment for 24 h drastically decreased SOD1 expression in retinal pericytes, and that this was restored by PEDF in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Reduction of ROS generation via up-regulation of SOD1 expression by PEDF in retinal pericytes.

A). Cultured human retinal pericytes were exposed to 100 µg/ml N-LDL or HOG-LDL with or without PEDF 160 nM for 24 h. Intracelluar ROS generation was measured by the DCF method and expressed as percentage of control (mean±SD, n=3). The values statistically different from N-LDL are indicated by # P<0.05, from HOG-LDL as ** P<0.01. B). Human retinal pericytes were treated with 100 µg/ml N-LDL or HOG-LDL in the presence or absence of PEDF at 10, 40 and 160 nM for 24 h. Expression of SOD1 was determined by western blot analysis. The same membrane was stripped and reblotted with the anti-β-actin antibody. Upper panel: representative image of western blot of SOD1. Lower panel: SOD1 expression quantified by densitometry and expressed as % of control (mean±SD, n=4). The values statistically different from N-LDL are indicated by # P<0.05, from HOG-LDL as * P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that oxidized, glycated LDL increased ROS generation, nitric oxide production and peroxynitrite formation, which subsequently activated NF-κB pathway, leading to over-production of MCP-1 in retinal pericytes. PEDF ameliorates oxidative stress and suppresses NF-κB activation and thus, reduces MCP-1 production. The inhibitory effect of PEDF on MCP-1 production contributes to its salutary role in reducing vascular leakage and inhibiting neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy.

Pericytes and endothelial cells are the two major cell components of retinal blood capillaries. Pericytes are traditionally believed not to be in direct contact with the circulation because of the inner blood retinal barrier. However, capillary leakage occurs early in diabetic retinopathy, and extravasation and entrapment of LDL in the sub-endothelial space may allow for continuing glycation and oxidation (processes already started in the circulation), leading to local accumulation of various concentrations of severely modified particles (Qaum, et al. 2001; Zhang, et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2006). In a recent study, using immunostaining we showed that both apoB and oxidized LDL are present in human retina in the presence of diabetes, in amounts proportional to the severity of diabetic retinopathy, but are entirely absent in non-diabetic retina (Wu et al. 2008). Consistent with this, Qaum et al. (Qaum et al. 2001) demonstrated that in rats, after induction of diabetes, the retinal vasculature is permeable to microspheres as large as 100nm in diameter, whereas by comparison, LDL particles are much smaller with a diameter of ~20nm. Further, accumulation of LDL in the vessel wall may be particularly high, as evidenced by the finding of a >2-fold higher level of LDL within the intima of normal human aortas than in plasma (Smith and Staples 1982), suggesting retention of the particles. Also in human arteries, the concentration of oxidized LDL in atherosclerotic plaques was found to be 70 times higher than in plasma (Nishi, et al. 2002). Given the complexity of this situation, we chose the LDL concentration of100µg protein/ml for our studies. We believe that this reflects a conservative estimate of conditions in the retina in vivo in the presence of diabetes, since the concentration range of apoB in normal plasma is 700–1200 µg/ml (Nishi et al. 2002).

We reported recently that PEDF is a potent endogenous anti-inflammatory factor(Zhang et al. 2006). Decreased intraocular PEDF levels have been observed in patients with diabetic retinopathy and in animal models of type 1 diabetes and spontaneous uveitis (Boehm, et al. 2003; Hauck, et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2006). Administration of PEDF into the vitreous significantly inhibits leukostasis and reduces vascular permeability in the retina in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, suggesting a potential role of PEDF on leukocyte/monocyte activation and infiltration in diabetic retinopathy(Yamagishi, et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006). Recent in vitro and in vivo studies showed that PEDF substantially suppresses macrophage activation and induces macrophage apoptosis and necrosis(Ho et al. 2008; Zamiri et al. 2006). Our results demonstrated that PEDF significantly decreases HOG-LDL-induced MCP-1 production in retinal pericytes. Moreover, we previously showed that a single dose intravitreal injection of PEDF drastically decreases MCP-1 expression in the retina of diabetic animals (Zhang et al. 2006). These results indicate that in addition to inhibiting macrophage activation and inducing macrophage death, PEDF is likely able to ameliorate monocyte/macrophage recruitment into the retina by suppressing MCP-1 production. Recent studies showed that over-production of MCP-1 in the retina and recruitment of hematogenous macrophages into the retina plays a causative role in retinal neovascularization in ischemia-induced retinopathy (Davies et al. 2006; Shen, et al. 2007). Thus, future studies are warranted to determine if inhibition of monocyte/macrophage recruitment and activation is a novel mechanism responsible the anti-angiogenesis effect of PEDF in diabetic retinopathy.

NF-kappa B is activated by a variety of stimuli and plays a critical role in the regulation of multiple cytokines, such as ICAM-1 and MCP-1 (Kowluru and Koppolu 2002; Renier et al. 2003; Sonoki et al. 2002), although other transcriptions factors, e.g. activator protein-1 (AP-1) have been shown to be partially responsible for MCP-1 regulation (Chen, et al. 2004). Previous studies have demonstrated that oxidized LDL and glycoxidized LDL are potent inducers of NF-kappa B activation in vascular cells and monocyte/macrophages (Do carmo, et al. 1998; Sonoki et al. 2002). Moreover, results from electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) assays showed that oxidized glycated LDL- and oxidized LDL induced MCP-1 expression via NF-kappa B activation. In the present study, we demonstrated that HOG-LDL caused translocation of NF-κB from cytoplasm to nucleus, which was blocked by PEDF. Although nuclear translocation of NF-κB does not represent direct evidence of NF-kappa activation, translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus is an essential step for subsequent DNA binding and transcription activation. Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation by PEDF would thus suppress subsequent NF-κB DNA binding and activation. Interestingly, previous studies showed that activation of NF-κB in neurons is responsible for the neuroprotective activity of PEDF(Yabe, et al. 2001). In our present study, we did not observe a protective effect of PEDF on HOG-LDL-induced apoptosis of pericytes nor activation of NF-κB by PEDF (data not shown), suggesting that the effect of PEDF on NF-κB activation is cell-type specific.

Taken together, the present study demonstrates that PEDF alleviated HOG-LDL-induced MCP-1 overproduction through blockade of NF-κB activation. The inhibitory effect of PEDF on oxidative stress was attributed to its anti-inflammatory activity on macrophage recruitment, and thus may contribute to the anti-angiogenesis effect of PEDF in diabetic retinopathy.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grant P20RR024215, JDRF grants 5-2007-793 and 18-2007-860, and a research award from OCAST.

REFERENCE

- Abu El-Asrar AM, Van Damme J, Put W, Veckeneer M, Dralands L, Billiau AL, Missotten L. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in proliferative vitreoretinal disorders. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth JL, Yu Y, Song W, Lu K, Dashti A, Huang Y, Argraves WS, Lyons TJ. Oxidised, glycated LDL selectively influences tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 gene expression and protein production in human retinal capillary pericytes. Diabetologia. 2007 Oct;50(10):2200–2208. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0768-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm BO, Lang G, Volpert O, Jehle PM, Kurkhaus A, Rosinger S, Lang GK, Bouck N. Low content of the natural ocular anti-angiogenic agent pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) in aqueous humor predicts progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 2003;46:394–400. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YM, Chiang WC, Lin SL, Wu KD, Tsai TJ, Hsieh BS. Dual regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells by nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1: modulation by type III phosphodiesterase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:978–986. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick M, Chew EY, Chan CC, Kruth HS, Murphy RP, Ferris FL., 3rd Histopathology and regression of retinal hard exudates in diabetic retinopathy after reduction of elevated serum lipid levels. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2126–2133. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MH, Eubanks JP, Powers MR. Microglia and macrophages are increased in response to ischemia-induced retinopathy in the mouse retina. Mol Vis. 2006;12:467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, Crawford SE, Xu H, Benedict W, Bouck NP. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science. 1999;285:245–258. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do carmo A, Ramos P, Reis A, Proenca R, Cunha-vaz JG. Breakdown of the inner and outer blood retinal barrier in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Experimental Eye Research. 1998;67:569–575. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Remessy AB, Behzadian MA, Abou-Mohamed G, Franklin T, Caldwell RW, Caldwell RB. Experimental diabetes causes breakdown of the blood-retina barrier by a mechanism involving tyrosine nitration and increases in expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1995–2004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong DS, Aiello L, Gardner TW, King GL, Blankenship G, Cavallerano JD, Ferris FL, 3rd, Klein R, American DiabetesA. Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:226–229. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Li Y, Gee S, Dudley A, Fant J, Crosson C, Ma JX. Down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and up-regulation of pigment epithelium-derived factor: a possible mechanism for the anti-angiogenic activity of plasminogen kringle 5. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:9492–9497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck SM, Schoeffmann S, Amann B, Stangassinger M, Gerhards H, Ueffing M, Deeg CA. Retinal Mueller glial cells trigger the hallmark inflammatory process in autoimmune uveitis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2121–2131. doi: 10.1021/pr060668y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández C, Segura RM, Fonollosa A, Carrasco E, Francisco G, Simó R. Interleukin-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and IL-10 in the vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med. 2005;22:719–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TC, Yang YC, Chen SL, Kuo PC, Sytwu HK, Cheng HC, Tsao YP. Pigment epithelium-derived factor induces THP-1 macrophage apoptosis and necrosis by the induction of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Le ML, Koizumi K, Esser C, Janicki H, Schraermeyer U, Kociok N, Fauser S, Kirchhof B, et al. A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J. 2004;18:1450–1452. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1476fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Koppolu P. Diabetes-induced activation of caspase-3 in retina: effect of antioxidant therapy. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:993–999. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000006572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons TJ, Li W, Wojciechowski B, Wells-Knecht MC, Wells-Knecht KJ, Jenkins AJ. Aminoguanidine and the effects of modified LDL on cultured retinal capillary cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamputu JC, Renier G. Gliclazide decreases vascular smooth muscle cell dysfunction induced by cell-mediated oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Metabolism. 2001;50:688–695. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.23297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Smith DG, Bhat M, Nagaraj RH. Glyoxalase I is critical for human retinal capillary pericyte survival under hyperglycemic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11864–11871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitamura Y, Takeuchi S, Matsuda A, Tagawa Y, Mizue Y, Nishihira J. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2001;215:415–418. doi: 10.1159/000050900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi K, Itabe H, Uno M, Kitazato KT, Horiguchi H, Shinno K, Nagahiro S. Oxidized LDL in carotid plaques and plasma associates with plaque instability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1649–1654. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000033829.14012.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrosova IG, Pacher P, Szabó C, Zsengeller Z, Hirooka H, Stevens MJ, Yorek MA. Aldose reductase inhibition counteracts oxidative-nitrosative stress and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in tissue sites for diabetes complications. Diabetes. 2005;54:234–242. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qaum T, Xu Q, Joussen AM, Clemens MW, Qin W, Miyamoto K, Hassessian H, Wiegand SJ, Rudge J, Yancopoulos GD, et al. VEGF-initiated blood-retinal barrier breakdown in early diabetes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:2408–2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renier G, Mamputu JC, Desfaits AC, Serri O. Monocyte adhesion in diabetic angiopathy: effects of free-radical scavenging. J Diabetes Complications. 2003;17:20–29. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder S, Palinski W, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Activated monocytes and granulocytes, capillary nonperfusion, and neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:81–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Xie B, Dong A, Swaim M, Hackett SF, Campochiaro PA. In vivo immunostaining demonstrates macrophages associate with growing and regressing vessels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4335–4341. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EB, Staples EM. Plasma protein concentrations in interstitial fluid from human aortas. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;217:59–75. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Barth JL, Lu K, Yu Y, Huang Y, Gittinger CK, Argraves WS, Lyons TJ. Effects of modified low-density lipoproteins on human retinal pericyte survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:390–395. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoki K, Yoshinari M, Iwase M, Iino K, Ichikawa K, Ohdo S, Higuchi S, Iida M. Glycoxidized low-density lipoprotein enhances monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: relation to lysophosphatidylcholine contents and inhibition by nitric oxide donor. Metabolism. 2002;51:1135–1142. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashimo A, Mitamura Y, Nagai S, Nakamura Y, Ohtsuka K, Mizue Y, Nishihira J. Aqueous levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med. 2004;21:1292–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Chen Y, Wilson K, Chirindel A, Ihnat M, Yu Y, Boulton ME, Szweda LI, Ma JX, Lyons TJ. Intra-retinal Leakage and Oxidation of LDL in Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008 Mar 24; doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1440. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe T, Wilson D, Schwartz JP. NFkappaB activation is required for the neuroprotective effects of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) on cerebellar granule neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43313–43319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Nakamura K, Takeuchi M, Imaizumi T. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) prevents diabetes- or advanced glycation end products (AGE)-elicited retinal leukostasis. Microvasc Res. 2006;72:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Yoshida A, Ishibashi T, Elner SG, Elner VM. Role of MCP-1 and MIP-1alpha in retinal neovascularization during postischemic inflammation in a mouse model of retinal neovascularization. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:137–144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0302117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamiri P, Masli S, Streilein JW, Taylor AW. Pigment epithelial growth factor suppresses inflammation by modulating macrophage activation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3912–3918. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SX, Ma J-X, Sima J, Chen Y, Hu MS, Ottlecz A, Lambrou GN. Genetic difference in susceptibility to the blood-retina barrier breakdown in diabetes and oxygen-induced retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:313–321. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62255-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SX, Sima J, Shao C, Fant J, Chen Y, Rohrer B, Gao G, Ma J-x. Plasminogen kringle 5 reduces vascular leakage in the retina of rat model of the oxygen-induced retinopathy and diabetes. Diabitologia. 2004;47:124–131. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SX, Wang JJ, Gao G, Shao C, Mott R, Ma J-x. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is an endogenous anti-inflammatory factor. FASEB J. 2006;20:323–325. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4313fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou MH, Shi C, Cohen RA. High glucose via peroxynitrite causes tyrosine nitration and inactivation of prostacyclin synthase that is associated with TP receptor-mediated apoptosis and adhesion molecule expression in cultured human aortic endothelial cells. Diabetes. 2002;51:198–203. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]