Abstract

Background

Recent years have seen an increased amount of natural language processing (NLP) work on full text biomedical journal publications. Much of this work is done with Open Access journal articles. Such work assumes that Open Access articles are representative of biomedical publications in general and that methods developed for analysis of Open Access full text publications will generalize to the biomedical literature as a whole. If this assumption is wrong, the cost to the community will be large, including not just wasted resources, but also flawed science. This paper examines that assumption.

Results

We collected two sets of documents, one consisting only of Open Access publications and the other consisting only of traditional journal publications. We examined them for differences in surface linguistic structures that have obvious consequences for the ease or difficulty of natural language processing and for differences in semantic content as reflected in lexical items. Regarding surface linguistic structures, we examined the incidence of conjunctions, negation, passives, and pronominal anaphora, and found that the two collections did not differ. We also examined the distribution of sentence lengths and found that both collections were characterized by the same mode. Regarding lexical items, we found that the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the two collections was low, and was lower than the divergence between either collection and a reference corpus. Where small differences did exist, log likelihood analysis showed that they were primarily in the area of formatting and in specific named entities.

Conclusion

We did not find structural or semantic differences between the Open Access and traditional journal collections.

Background

For much of the modern period of biomedical natural language processing (BioNLP) research, work in text mining has focused on abstracts of journal articles. Free and widely available via PubMed/MEDLINE in numbers previously unseen in most statistical text mining work, abstracts enabled a mass of work that has grown remarkably quickly [1]. In recent years, however, there has been both a growing awareness that full text articles are important, and an increasing amount of work using the full text of articles. As early as 2001, Blaschke and Valencia examined recoverability of databased protein-protein interactions from text and concluded that the ability to handle full text would be essential to achieving high-coverage performance [2]. Shah et al. examined the location of biologically relevant words in journal articles and found that although the density of biologically relevant terms is higher in the abstract than in the body of the article, there is much more relevant information in the body of the article than in the abstract [3]. Corney et al. (2004) provided a careful quantification of the costs of failing to work with full text, finding that more than half of the information in molecular biology papers was in the body of the text and not in the abstract [4].

At the same time, it became clear very early on that full text poses challenges that are different from those of abstracts. For example, Tanabe and Wilbur (2002) found that some sections (particularly Materials and Methods) tend to produce much higher rates of false positives on information extraction tasks than others [5]. Furthermore, the substantial length of full text articles as compared to abstracts means that it is likely more difficult to identify individual entities or events, due to the increased linguistic complexity of the text, and the use of longer-distance references. Preprocessing requirements alone can be prohibitively time-costly with full text. Even issues of character encodings and how various journals deal with them – solutions range from inserted gifs to HTML character entities to Unicode – are sufficient to throw off character-offset-based systems, which are increasingly popular.

These problems notwithstanding, recent years have seen an increased emphasis on working with full text papers (see e.g. [6] and [7] for papers that review a substantial amount of work using full text). However, much of this work is done with Open Access journal articles, and with the availability of the PubMed Central Open Access subset [8] of close to 90K biomedical publications (and growing), we expect research on full text to further concentrate on Open Access publications. Such work will assume that the Open Access articles are representative of biomedical publications in general and that methods developed for analysis of Open Access full text publications will generalize to the biomedical literature as a whole. This assumption requires investigation due to the possibility that there exist significant differences in format or content. For instance, the majority of open access journals have to date been exclusively electronic publications, often without formal restrictions on article length (such as the BioMed Central journals), where the lack of strict space constraints could certainly impact the language authors use to present their findings. Furthermore there is at least a perception that these journals often have quicker turnaround on the time from submission to publication [9], and that open access publications have higher community impact [10], both of which could affect the sort of research results that are submitted to open access journals. Similarly, the cost of publication of open access articles may mean that authors tend to submit longer articles combining more research results. The effect of such differences on the textual characteristics of the publications has not to our knowledge been previously explored.

If the basic assumption of the representativeness of Open Access publications is wrong, the cost to the community will be large, including not just wasted resources but also flawed science. This paper sets out to examine that assumption. Our null hypothesis is that traditional and Open Access publications are the same; we seek to find differences between them.

Results and Discussion

Results

Text collections

We developed or assembled four text collections for comparison.

• CRAFT is the Colorado Rich Annotation of Full Text corpus. This is a true corpus in the linguistic sense of that word – a static set of documents with associated linguistic and semantic annotations. The document set was assembled from the PubMed Central Open Access subset [8] with input from the Mouse Genome Informatics group at the Jackson Laboratory to ensure biological relevance. It focuses on mouse genomics. The corpus comprises 97 open access articles containing nearly 750K words.

• TraJour (Traditional Journals corpus) is a document collection that we assembled from traditional subscription-based journals, with the intent of collecting a set of texts that topically parallels the CRAFT corpus as closely as possible. This parallelism was achieved via shared Gene Ontology annotations (see the Methods section). TraJour consists of 99 articles and almost 600K words.

• Reference is a corpus based on the the Wall Street Journal corpus. This is a collection of newspaper articles that has been extensively annotated in the course of the Penn Treebank [11] and PropBank [12] projects. We took the raw text version from the Penn Treebank distribution. It contains about 1.1 million words.

• BioReference is a document collection which aims to be representative of full text biomedical publications in general, rather than being tailored to mouse genomics. It was constructed from a random subsample of two document collections: the TREC Genomics Corpus [13], containing full text publications from primarily subscription-based traditional journals, and the PubMed Central Open Access subset, containing exclusively Open Access publications. It is comparable in size to CRAFT and TraJour, at 650K words in 163 articles.

Characteristics that we compared in the corpora

We compared the corpora according to various surface-level characteristics as well as several linguistic phenomena. We performed comparisons of the statistical properties of the vocabularies of the corpora in order to identify important variations of language use among them. The two corpora of primary interest are the two semantically comparable corpora – CRAFT, our open access publication corpus, and TraJour, our traditional journal corpus.

We examined the incidence of a number of morphosyntactic/semantic phenomena in the four sets of documents. We selected them because each is known to have consequences for natural language processing: in particular, all of the morphosyntactic phenomena that we examined make the text mining task more difficult by introducing complexity and variability in the linguistic structures found in the text. The linguistic phenomena that we examined were negation, passivization, conjunction, and pronominal anaphora.

To examine negation, we counted every instance of the words no, not, neither, and nor, as well as the affix n't. To examine passivization, we counted instances of the strings ed by, en by, and ound by. This clearly underestimates the number of passives. For example, conjoined passive verbs, as in eEF2 kinase is phosphorylated and inhibited by SAPK4/p38 delta [14], will be undercounted. Similarly, intervening adverbials, as in MAPK is activated primarily by FGF in this context [15], will cause undercounting, as will bare passives (i.e. those without a subsequent by-phrase indicating the agent). However, it yields a reasonable approximation of the number of passives, and the undercounting applies proportionally to all four document sets, so the intra-corpus comparison probably remains valid, although we would need to do a separate analysis to verify this. To examine conjunction, we counted every instance of and, or, and but not. Finally, to examine pronominal anaphora, we counted every instance of any pronoun. In each case, we normalized the counts by the number of words in the corpus.

Table 1 reports the ratio of each phenomenon to the number of words in the four corpora, along with the absolute counts of each. The ratios for the two semantically matched corpora CRAFT (Open Access) and TraJour are similar to each other, and are more similar to each other than they are to the general Reference corpus. When compared to the BioReference corpus, the CRAFT and TraJour corpora are more similar to each other than to the BioReference on the proportion of pronouns and passives in the text. On the proportion of coordination and negatives, the BioReference corpus numbers are about halfway between the CRAFT and TraJour values, though all differences are small. The proximity to the BioReference measures on all of the linguistic dimensions indicates that the differences among them are minor and likely within the range of normal variation for the biomedical literature.

Table 1.

Incidence of syntactic/semantic phenomena

| CRAFT | TraJour | Reference | BioReference | |

| Document count | 97 | 99 | 2,500 | 163 |

| Sentence count | 43,694 | 35,997 | 53,107 | 32,895 |

| Avg. Sentence count | 450 | 364 | 21 | 202 |

| Token count | 717,166 | 598,331 | 1,096,976 | 654,493 |

| Type count | 41,574 | 49,394 | 40,139 | 38,801 |

| Stopword count | 238,542 | 193,905 | 453,264 | 238,077 |

| Stopword % | 33.3% | 32.4% | 41.3% | 36.4% |

| Avg. Document length | 7,393 | 6,044 | 439 | 4,015 |

| Avg. Sentence length | 22.5 | 24.7 | 26.4 | 27.8 |

| Types/Tokens | 5.8% | 8.3% | 3.7% | 5.9% |

| Tokens/Types | 17.3 | 12.1 | 27.3 | 16.9 |

| Negatives | 3,273 | 2,587 | 7,605 | 2,961 |

| Negatives % | 0.46% | 0.43% | 0.69% | 0.45% |

| Coordination | 25,237 | 23,706 | 26,019 | 25,059 |

| Coordination % | 3.52% | 3.96% | 2.37% | 3.83% |

| Pronouns | 18,874 | 15,603 | 57,406 | 20,699 |

| Pronouns % | 2.63% | 2.61% | 5.23% | 3.16% |

| Passives | 2,783 | 2,587 | 2,661 | 3,172 |

| Passives % | 0.39% | 0.43% | 0.24% | 0.48% |

This table represents the counts of linguistic phenomena determined from our four document sets, CRAFT (open access), TraJour (traditional journals), Reference (Wall Street Journal), and BioReference (full text biomedical publications).

The directions of the differences with the reference corpus are mostly not surprising. Passives are more common in the two semantically matched corpora (0.39% and 0.43%) and in the BioReference (0.48%) than they are in the Reference corpus (0.24%). This accords with the observation that passives are almost caricatural of scientific writing and are quite common in biomedical language [16].

Conjunctions are more frequent in the scientific corpora than in the reference corpus. As Biber et al. [17] point out in their corpus-based study of the grammar of English, comparison of competing hypotheses is a dominant theme in scientific writing. Comparison is often realized by use of conjunctions and by asserting the competing hypotheses. Thus the results are in line with previous research in this area, although a separate analysis would be required to establish what proportion of the conjunctions link competing hypotheses.

The pattern of incidence of negations is also in line with other contrastive reports of negation in the academic and news registers [17]. Incidence of negatives in the two semantically matched corpora and the BioReference reference collection were quite similar – 0.46% for CRAFT, 0.43% for TraJour, and 0.45% for BioReference. However, they were much more common in the WSJ reference than in the three scientific corpora, at 0.69%. This is thought to be related to the use of other terms to express contrast in academic discourse, such as although, however, nevertheless, and on the other hand [17](81–82).

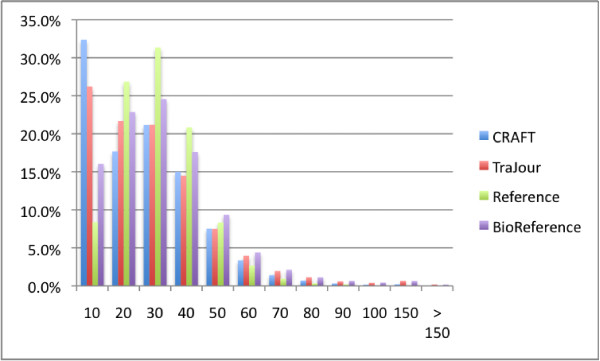

We measured the distribution of sentence lengths because sentence length has implications for syntactic parser performance. Parser accuracy falls as sentence length increases: thus, if there were a difference in sentence lengths between the CRAFT and TraJour corpora, that would indicate that one would present more challenges than the other for an important class of linguistic analysis. Figure 1 shows the histogram of sentence lengths in the four corpora. The mode for both CRAFT and TraJour is at the 0–10 words bin: they do not differ with respect to sentence lengths. In contrast, the WSJ reference differs markedly with respect to sentence length, showing a mode of 20–30 words. Surprisingly, the BioReference also has a mode of 20–30 words; we do not know why it should be more like the WSJ than like the other scientific documents.

Figure 1.

Sentence length distribution. Sentence length distributions for the four document sets, measured as the relative proportion of the sentences in the corpus of a particular length. The data here is binned – "10" means a sentence length of 1–10 tokens, "20" 11–20 tokens, etc.

The preceding measures are all concerned with linguistic (conjunction, passivization, etc.) or structural (sentence length) feature distributions and their implications for processing difficulty. We now turn to measures that are more reflective of the semantic content of the corpora.

To further explore the possibility of important differences between CRAFT and TraJour, we looked at two measures of lexical difference and similarity. The first of these is Kullback-Leibler divergence [18], or relative entropy, and the second is log likelihood [19].

Kullback-Leibler divergence measures the divergence between two probability distributions. Here, we consider the probability of each word w in the vocabulary V formed by combining the sets of unique words in two corpora c1 and c2. It is calculated as shown in equation (1), and it is converted to a symmetric distance with equation (2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

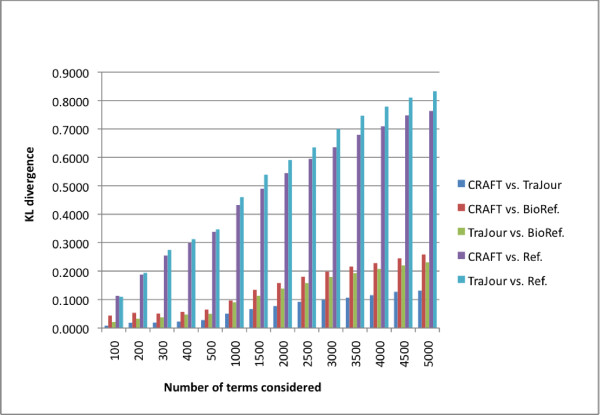

Intuitively, as two distributions become more different, the value for KL divergence increases. We assume a threshold value of 0.005 corresponds to near identity of the distributions. We calculated the KL divergence between CRAFT and TraJour and between each of the two and the reference corpora. We ordered words by frequency in the merged vocabulary of the corpora and then calculated the KL divergence for different values of the top n most frequent words, from the 100 most frequent words to the 10,000 most frequent words, comparing the probability distributions for those selected words in the two corpora. We employed Laplace (add-one) smoothing to accommodate for words which occurred in one corpus but not in the other.

Figure 2 shows the pattern of values; Table 2 shows actual values for a subset of the data points at the two extremes of the frequency list. For the top 500 words, CRAFT and TraJour are nearly identical. In fact we see that the KL-divergence numbers dip below zero in this case. KL-divergence has a theoretical lower bound of 0; the violation of the bound here is a result of error introduced by our smoothing method. This indicates that the two probability distributions have near-complete overlap in the vocabulary for the most frequent terms, and that the probabilities of the shared terms do not differ significantly in the two corpora. The probability distributions for CRAFT and TraJour do not differ above the assumed identity threshold of 0.005 until 500 words are considered, and then only slightly.

Figure 2.

Kullback-Leibler divergences. KL divergences at the top n terms for CRAFT (open access) versus TraJour (traditional journal) and for each target corpus against the Wall Street Journal reference corpus and the BioReference corpus.

Table 2.

KL divergence of term probability distributions, CRAFT versus TraJour

| n terms | CRAFT v. TraJour | CRAFT v. BioRef. | TraJour v. BioRef. | CRAFT v. Ref. | TraJour v. Ref. |

| 100 | -0.006925696 | 0.043712192 | 0.020944793 | 0.161024124 | 0.16794174 |

| 200 | -0.007124725 | 0.053331913 | 0.03214335 | 0.236587232 | 0.257485466 |

| 300 | -0.005614059 | 0.050666423 | 0.037185528 | 0.319120526 | 0.341360939 |

| 400 | -0.001556702 | 0.05700178 | 0.047472912 | 0.36994002 | 0.386699809 |

| 500 | 0.007515454 | 0.064545725 | 0.04958329 | 0.411526361 | 0.421816134 |

| 1000 | 0.041726207 | 0.096664283 | 0.089761915 | 0.513431974 | 0.548467754 |

| 1500 | 0.06325848 | 0.134310701 | 0.11321715 | 0.577868266 | 0.641503517 |

| 2000 | 0.078438422 | 0.158005507 | 0.138857184 | 0.642507317 | 0.69333303 |

| 2500 | 0.098753882 | 0.180169586 | 0.157642056 | 0.697711222 | 0.746388986 |

| 3000 | 0.108449436 | 0.19872906 | 0.179409293 | 0.746911394 | 0.817412333 |

| 3500 | 0.118474793 | 0.215904498 | 0.193018939 | 0.794260113 | 0.87476207 |

| 4000 | 0.132179627 | 0.228193197 | 0.207559096 | 0.830437495 | 0.904734502 |

| 4500 | 0.145510397 | 0.244716631 | 0.21989223 | 0.872842604 | 0.942379721 |

| 5000 | 0.152931092 | 0.258427849 | 0.230542781 | 0.89245553 | 0.969431637 |

This table shows the KL divergence of the probability distributions of words in the corpora. Each row in the table corresponds to the figure for the top n most frequent terms in the corpora.

In contrast, if either corpus is compared against the reference corpus, they are drastically different, with KL divergences for the top 100 words of 0.161 and 0.167, respectively – far above the assumed identity threshold. Even compared with the BioReference corpus, the divergence is well above this threshold (0.044 and 0.021 @100 words), suggesting that there are significant lexical differences between the mouse genome corpora and general biomedical text, while there do not appear to be lexical differences simply due to the mode of publication of the text.

KL divergence scores indicate that CRAFT and TraJour differ very little with respect to semantic content; analysis of the log likelihood scores helps us understand where precisely the two scientific corpora do differ. It will be seen that much of the difference between them is due to formatting and to named entities. Log likelihood values uncover terms that distinguish one corpus from another, by identifying terms that have the most significant relative frequency difference [20]. For each term in the frequency lists derived from two corpora being compared, we calculate the log likelihood statistic. It is based on the expected value for a term t in corpus i, where Ni is the number of word types in corpus i and Oi is the number of occurrences of t in corpus i. It is calculated as shown in equations (3)–(4), with (3) representing the expected value for a term in corpus i, and (4) the log likelihood for that term. Ei tells us how many instances of the term we would expect to see in corpus i if the occurrences were evenly distributed across the two corpora. The Log Likelihood measures how far off from that ideal the actual occurrences are. This measure is argued by [19] to be preferable for corpus analysis to statistics that assume a normal distribution (such as the chi squared statistic), due to its ability to more accurately analyze rare events.

| (3) |

| (4) |

We see the results of the log likelihood analysis in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Table 3.

Log Likelihood analysis of terms in CRAFT vs. TraJour

| CRAFT | TraJour | LL |

| figure | 2318.9 | |

| doi | 1099.3 | |

| window | 854.6 | |

| fig | 756.7 | |

| text | 743.6 | |

| abstract | 721.9 | |

| mice | 678.2 | |

| pp | 608.5 | |

| hair | 601.8 | |

| 588.1 | ||

| x1 | 570.6 | |

| full | 550.8 | |

| pgc | 516.9 | |

| ?m | 502.3 | |

| e2 | 465.6 | |

| chm | 460.5 | |

| gp | 435.8 | |

| ephrin | 418.1 | |

| qtl | 381.5 | |

| view | 363.9 | |

| °c | 338.5 | |

| sam68 | 328.8 | |

| atrx | 322.0 | |

| bhlh | 320.2 | |

| ptds | 311.8 | |

| version | 305.1 | |

| olfactory | 301.0 | |

| ca | 294.9 | |

| mena | 294.3 | |

| ap | 292.2 | |

| rb | 292.0 | |

| sox1 | 288.2 | |

| null | 287.4 | |

| file | 278.4 | |

| p300 | 270.1 | |

| -catenin | 264.0 | |

| -1? | 262.1 | |

| kinase | 256.8 | |

| binding | 256.2 | |

| nk | 256.0 | |

| snail | 256.0 | |

| -1?? | 253.6 | |

| ited | 251.2 | |

| larger | 247.3 | |

| states | 244.0 | |

| 5? | 243.9 | |

| nxt1 | 241.7 | |

| strains | 240.3 | |

| articles | 239.6 | |

| wk | 239.4 | |

These are the results of log likelihood analysis of all terms in the CRAFT (open access publications) and TraJour (traditional journals) corpora, ranked by the largest difference.

Table 4.

Log Likelihood analysis of terms in CRAFT vs. BioReference

| CRAFT | BioReference | LL |

| mice | 3755.8 | |

| abstract | 1830.7 | |

| doi | 1650.5 | |

| mouse | 1489.8 | |

| window | 1229.4 | |

| free | 1183.7 | |

| embryos | 1151.8 | |

| figure | 1017.2 | |

| null | 922.5 | |

| embryonic | 657.2 | |

| hair | 611.3 | |

| pgc | 539.9 | |

| ?m | 536.9 | |

| e2 | 532.4 | |

| olfactory | 512.4 | |

| ephrin | 503.2 | |

| development | 492.1 | |

| mutant | 480.3 | |

| view | 471.3 | |

| wild | 465.8 | |

| allele | 455.9 | |

| expression | 451.1 | |

| qtl | 430.6 | |

| version | 424.9 | |

| gene | 416.4 | |

| type | 411.4 | |

| homozygous | 407.4 | |

| larger | 405.2 | |

| knockout | 394.6 | |

| shh | 387.8 | |

| heterozygous | 384.8 | |

| differentiation | 376.9 | |

| fig | 370.8 | |

| °c | 361.8 | |

| atrx | 356.7 | |

| sam68 | 351.5 | |

| sections | 341.2 | |

| new | 336.1 | |

| ptds | 333.3 | |

| ap | 332.3 | |

| es | 324.5 | |

| women | 322.5 | |

| sox1 | 320.3 | |

| targeted | 317.0 | |

| annexin | 316.8 | |

| defects | 312.0 | |

| limb | 311.4 | |

| targeting | 310.0 | |

| cleavage | 306.5 | |

| a7 | 298.7 | |

These are the results of log likelihood analysis of all terms in the CRAFT and BioReference corpora, ranked by the largest difference.

Table 5.

Log Likelihood analysis of terms in TraJour vs. BioReference

| TraJour | BioReference | LL |

| mouse | 1260.6 | |

| mice | 1219.8 | |

| free | 911.8 | |

| embryos | 704.9 | |

| 690.2 | ||

| text | 688.1 | |

| pp | 569.5 | |

| full | 543.5 | |

| expression | 514.6 | |

| medline | 512.5 | |

| crossref | 497.6 | |

| embryonic | 479.8 | |

| development | 447.7 | |

| chm | 443.4 | |

| patients | 425.4 | |

| x1 | 422.4 | |

| risk | 372.3 | |

| bhlh | 357.7 | |

| gp | 356.8 | |

| slap-2 | 354.7 | |

| figure | 354.6 | |

| dpc | 331.1 | |

| jmj | 331.1 | |

| women | 329.3 | |

| tap | 326.3 | |

| pb | 310.7 | |

| nxt1 | 304.5 | |

| isi | 297.6 | |

| p300 | 295.8 | |

| mena | 286.7 | |

| endoderm | 285.6 | |

| hybridization | 275.7 | |

| exercise | 273.5 | |

| cited4 | 273.4 | |

| tbx2 | 270.5 | |

| zfp-57 | 266.0 | |

| otx2 | 264.6 | |

| neural | 263.8 | |

| orderarticleviainfotrieve | 261.3 | |

| sti | 258.9 | |

| abstract | 258.6 | |

| ko | 258.4 | |

| mznf8 | 257.2 | |

| heterozygous | 255.9 | |

| embryo | 252.2 | |

| gl | 249.8 | |

| domain | 249.5 | |

| -catenin | 246.6 | |

| mutants | 245.3 | |

| chl1 | 243.9 | |

These are the results of log likelihood analysis of all terms in the TraJour and BioReference corpora, ranked by the largest difference.

Table 6.

Log Likelihood analysis of terms in CRAFT vs. Reference

| CRAFT | Reference | LL |

| mice | 9705.6 | |

| 's | 9351.0 | |

| said | 7898.0 | |

| cells | 6565.1 | |

| million | 5684.6 | |

| expression | 5272.3 | |

| figure | 4528.4 | |

| 't | 4392.8 | |

| he | 4284.3 | |

| cell | 4224.9 | |

| mouse | 3914.6 | |

| mr | 3850.0 | |

| year | 3788.4 | |

| gene | 3766.7 | |

| company | 3362.6 | |

| protein | 3221.6 | |

| it | 3199.2 | |

| to | 2986.3 | |

| will | 2948.4 | |

| type | 2833.5 | |

| were | 2803.0 | |

| embryos | 2619.0 | |

| its | 2564.8 | |

| stock | 2475.9 | |

| genes | 2442.7 | |

| doi | 2431.4 | |

| mutant | 2383.2 | |

| wild | 2317.2 | |

| about | 2192.3 | |

| new | 2158.6 | |

| analysis | 2140.2 | |

| his | 2107.7 | |

| and | 1972.7 | |

| who | 1843.6 | |

| corp | 1769.0 | |

| they | 1696.4 | |

| null | 1689.1 | |

| dna | 1596.9 | |

| in | 1585.8 | |

| al | 1557.6 | |

| et | 1484.3 | |

| shares | 1477.7 | |

| inc | 1475.9 | |

| would | 1468.6 | |

| receptor | 1458.6 | |

| shown | 1396.3 | |

| differentiation | 1366.1 | |

| using | 1333.2 | |

| has | 1332.9 | |

| fig | 1326.0 | |

These are the results of log likelihood analysis of all terms in the CRAFT and the general Reference corpora, ranked by the largest difference.

Table 7.

Log Likelihood analysis of terms in TraJour vs. Reference

| TraJour | Reference | LL |

| 's | 8358.8 | |

| cells | 7680.7 | |

| said | 6854.5 | |

| expression | 5262.0 | |

| million | 4975.7 | |

| mice | 4833.1 | |

| mr | 4607.9 | |

| cell | 4285.6 | |

| protein | 4074.2 | |

| fig | 3881.0 | |

| 't | 3808.8 | |

| he | 3660.9 | |

| to | 3464.4 | |

| mouse | 3425.1 | |

| year | 3165.5 | |

| and | 3144.6 | |

| it | 2864.9 | |

| will | 2858.5 | |

| company | 2820.1 | |

| et | 2690.1 | |

| were | 2680.4 | |

| al | 2555.7 | |

| gene | 2389.7 | |

| stock | 2196.0 | |

| biol | 2180.8 | |

| proteins | 2163.8 | |

| binding | 2009.0 | |

| type | 1990.1 | |

| its | 1900.2 | |

| domain | 1897.9 | |

| shown | 1873.2 | |

| about | 1859.1 | |

| embryos | 1822.6 | |

| his | 1701.0 | |

| they | 1700.4 | |

| who | 1694.5 | |

| would | 1623.4 | |

| mutant | 1598.6 | |

| analysis | 1592.6 | |

| wild | 1591.2 | |

| abstract | 1560.2 | |

| corp | 1546.0 | |

| receptor | 1537.5 | |

| up | 1483.3 | |

| activity | 1404.0 | |

| in | 1385.2 | |

| expressed | 1375.6 | |

| genes | 1337.5 | |

| pp | 1316.4 | |

| on | 1304.3 | |

These are the results of log likelihood analysis of all terms in the TraJour and the general Reference corpora, ranked by the largest difference.

We can analyze this data in terms of two characteristics: the magnitude of the differences, and the semantic nature of the words in terms of which the various pairs of corpora differ.

With respect to the magnitude of differences, we see that the most different words in the two content-matched corpora, CRAFT and TraJour, are far less different than the most different words between either of those corpora and either of the reference corpora: the most different word between CRAFT and TraJour is figure, with a log likelihood of 2318.9, while the most different word between CRAFT and BioReference is mice with a log likelihood of 3755.8. The most different word between TraJour and BioReference is mouse, with a log likelihood of 1260.6. (The differences between the two content-matched corpora and the WSJ reference corpus are considerably higher, but we omit them from consideration here because the comparison against the BioReference corpus is a much more stringent comparison.) With respect to the semantic content of the words in terms of which the various pairs of corpora differ, we see clear patterns. The six most different words between the two semantically matched corpora CRAFT and TraJour all reflect formatting: figure and doi, which are overrepresented in CRAFT as compared to TraJour, and window, fig, text, and abstract, which are overrepresented in TraJour. In fact, of the 50 most different terms between the two corpora, at least a quarter of them reflect formatting differences and artifacts of the text conversion routines – the preceding six terms, plus pp, ?m, °c, null, -1?, -1??, and 5?. Many of the remaining differences are due to the specific named entities that occur in each corpus. However, when we compare either of the two semantically matched corpora CRAFT and TraJour against BioReference, we see content words such as mice, mouse, and embryos ranked much higher, and we see more overlap among the most significant terms. In Table 8 the top 50 terms, by TF*IDF (Term Frequency * Inverse Document Frequency) calculated with respect to the Reference corpus term document frequencies, are shown and the significant overlap in the vocabularies of CRAFT and TraJour is clear. This indicates that not only are the Open Access and traditional documents similar in terms of surface linguistic phenomena, but that authors talk about the same things in them (in this case, mouse genomics), as compared against a set of documents selected from across all of biomedicine.

Table 8.

TF*IDF-ranked terms in the corpora

| CRAFT | TraJour | Reference | BioReference | ||||

| mice | 0.435821989 | cells | 0.336961638 | mr | 0.121256579 | cells | 0.320612568 |

| cells | 0.270086285 | mice | 0.23486562 | says | 0.118389148 | fig | 0.205308437 |

| expression | 0.216037704 | expression | 0.23159711 | that | 0.118092658 | cell | 0.20214811 |

| mouse | 0.178144406 | fig | 0.220320662 | he | 0.102566064 | abstract | 0.190193446 |

| cell | 0.172290914 | protein | 0.195781243 | market | 0.091669921 | medline | 0.188483175 |

| gene | 0.163204203 | cell | 0.187501368 | 's | 0.088505453 | protein | 0.177454065 |

| embryos | 0.151251462 | mouse | 0.167860719 | million | 0.08479812 | fulltext | 0.140623811 |

| protein | 0.14510293 | biol | 0.135330482 | is | 0.083961293 | expression | 0.138198756 |

| figure | 0.12789903 | et | 0.120455574 | as | 0.081560405 | orderarticle... | 0.119943839 |

| doi | 0.122095859 | gene | 0.117032939 | his | 0.081293607 | genes | 0.109091523 |

| genes | 0.120878869 | al | 0.1166477 | on | 0.079143554 | proteins | 0.106029999 |

| mutant | 0.119701823 | embryos | 0.113119754 | stock | 0.078988492 | gene | 0.098232094 |

| null | 0.097585044 | proteins | 0.110513285 | they | 0.078407133 | were | 0.096137225 |

| type | 0.093527187 | domain | 0.093587827 | at | 0.075765418 | binding | 0.094229295 |

| wild | 0.085050648 | binding | 0.093519941 | but | 0.075548004 | window | 0.085695981 |

| differentiation | 0.078946407 | mutant | 0.086691778 | billion | 0.073818895 | induced | 0.085566187 |

| analysis | 0.076546987 | receptor | 0.085026763 | have | 0.073662149 | biol | 0.085231028 |

| receptor | 0.075227992 | pp | 0.081740644 | are | 0.072364352 | ml | 0.083458459 |

| dna | 0.073316012 | mutants | 0.077608416 | be | 0.071025302 | min | 0.083015317 |

| pcr | 0.073162003 | abstract | 0.077359299 | with | 0.068584195 | al | 0.078391977 |

| biol | 0.072197936 | antibody | 0.076735615 | it | 0.067830211 | et | 0.077346227 |

| fig | 0.070585942 | cdna | 0.076317095 | was | 0.067707989 | analysis | 0.076920249 |

| were | 0.070224935 | genes | 0.07615871 | 't | 0.066475036 | mm | 0.073266187 |

| allele | 0.069948445 | membrane | 0.075929698 | in | 0.065890951 | mice | 0.072205176 |

| al | 0.067582502 | transcription | 0.073863584 | trading | 0.065657748 | shown | 0.070980579 |

| mutants | 0.066734887 | type | 0.073860554 | would | 0.06509097 | data | 0.06877046 |

| embryonic | 0.0644353 | were | 0.072302222 | said | 0.064915624 | ph | 0.067550112 |

| et | 0.06344436 | sequence | 0.070485632 | to | 0.064419151 | activation | 0.06720991 |

| staining | 0.061271839 | kinase | 0.070118752 | has | 0.064175458 | receptor | 0.066788269 |

| neurons | 0.059343704 | pcr | 0.070118752 | by | 0.063766297 | sequence | 0.066026426 |

| proteins | 0.058555579 | shown | 0.069422034 | shares | 0.063615252 | antibody | 0.065025557 |

| mm | 0.057094213 | X1 | 0.068956563 | company | 0.063043995 | human | 0.064973329 |

| olfactory | 0.056987095 | activation | 0.065599127 | their | 0.062731731 | using | 0.064071093 |

| transcription | 0.056130146 | wild | 0.065140388 | for | 0.062641744 | dna | 0.063146568 |

| signaling | 0.055582376 | analysis | 0.06314115 | bonds | 0.061745073 | crossref | 0.062926201 |

| phenotype | 0.052916588 | wt | 0.062499956 | will | 0.061422042 | activity | 0.058794757 |

| observed | 0.05206838 | dna | 0.060635915 | year | 0.061329696 | rna | 0.058294133 |

| e2 | 0.051952521 | chem | 0.060606544 | new | 0.060716109 | observed | 0.05785548 |

| shown | 0.050532729 | 0.060433841 | were | 0.06062604 | with | 0.057545637 | |

| homozygous | 0.050131504 | mrna | 0.060175577 | or | 0.060257745 | these | 0.057379774 |

| function | 0.049871842 | rna | 0.059552487 | an | 0.060255469 | study | 0.056368432 |

| muscle | 0.049628485 | ca | 0.055251655 | from | 0.059225401 | free | 0.056039813 |

| data | 0.049494253 | differentiation | 0.055139424 | we | 0.059174038 | mediated | 0.055983639 |

| antibody | 0.048131217 | insulin | 0.05440163 | index | 0.059103846 | serum | 0.05494964 |

| chromosome | 0.048033587 | activity | 0.053267608 | some | 0.058883875 | actin | 0.054506498 |

| we | 0.047444291 | expressed | 0.053108054 | one | 0.058690763 | kinase | 0.053029357 |

| sequence | 0.047236181 | embryonic | 0.052726312 | more | 0.058586253 | ?c | 0.052586215 |

| transgenic | 0.046764407 | signaling | 0.052369358 | stocks | 0.058457121 | we | 0.051671671 |

| using | 0.046658651 | molecular | 0.052281469 | sales | 0.058224908 | figure | 0.051378087 |

| pgc | 0.045739642 | amino | 0.052137849 | this | 0.05791668 | amino | 0.050216424 |

These are the top 50 terms in each corpus, by TF*IDF (Term Frequency * Inverse Document Frequency). Terms highlighted in bold in the CRAFT and TraJour columns indicate terms that are shared among these two corpora within the top 50 terms of each corpus; terms highlighted in bold in the BioReference column are shared among all three corpora in the top 50 terms. There is clearly significant overlap between CRAFT and TraJour in their contentful terms.

Discussion

In terms of linguistic phenomena such as conjunction, passivization, negation, and pronominal anaphora, the content-matched Open Source and traditional publications do not differ from each other. They also do not differ in terms of sentence length. When compared against reference corpora, they do differ from these more general document sets, indicating that if the Open Source and traditional journals did differ from each other, our methods would have uncovered those differences.

The two target corpora analyzed (CRAFT and TraJour) are both in the molecular biology domain, and more specifically mouse genomics. As such, the results and conclusions, strictly interpreted, apply only to the particular datasets we examined. Based on the analysis of the factors that might lead to textual variation (see Background), it would be conservative to assume that these results generalize to the molecular biomedical literature as a whole. We believe that generalizing these results to the entire biomedical literature, or even all peer reviewed scientific publications, is reasonable, although additional testing may be warranted for areas with substantially different cultures of scientific practice.

Conclusion

We tried hard to find differences between the CRAFT and TraJour document sets. We mostly failed. Research on Open Access documents applies to traditional, subscription-only journals.

Methods

Construction of the TraJour corpus

The document set was selected by collecting the set of Gene Ontology annotations with an evidence code of Traceable Author Statement (see Gene Ontology 2000 for an explanation of evidence codes) from the Mouse Genome Institute's Gene Ontology annotation file [21] for documents in the CRAFT corpus, eliminating two annotations that were overly generic (GO:0005515 "protein amino acid binding" and GO:0005634, "cell nucleus"), and then randomly selecting 100 articles from other articles associated with those Gene Ontology terms. These were all identified as coming from traditional subscription-based journals. One of the selected articles was discarded due to our inability to access the full text of the article. The remaining 99 articles form our corpus, and contain over 650K words. Most of these articles were obtained as full text HTML from the individual publisher's websites, though 14 articles were only available as PDFs. To convert those PDFs to plain text, we used a conversion tool from the USC Information Sciences Institute. The HTML files were (imperfectly) processed to handle character entities and to remove javascript, frames, HTML tags and other non-contentful text prior to the analysis.

Construction of the BioReference corpus

One hundred PubMed identifiers were selected at random from each of two sources: the 2006 TREC Genomics Corpus [13] and the PubMed Central Open Access subset [8]. These two sources were used because they are the only two large collections of full textpublications that we have access to. The TREC Genomics Corpus was collected originally for the Genomics Track of the Text Retrieval Conference. The 2006 corpus contains over 162K articles from 49 journals, ranging from the American Journal of Epidemiology to several American Journal of Physiology journals (e.g. Heart and Circulatory Physiology), and as such the corpus has quite broad coverage of biomedicine despite the "Genomics" name. Our selection included 41 articles from The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 12 from Blood, 4 each from Human Reproduction, Human Molecular Genetics, and the Journal of Applied Physiology, and 1–3 each from 20 other journals.

The portion of the BioReference corpus randomly selected from the PubMed Central Open Access included publications from Nucleic Acids Research (23 articles), Environmental Health Perspectives (9 articles), Ulster Medical Journal (4 articles), BMC Genomics (4 articles), Medical History (4 articles) and 44 other journals contributing 1 or 2 articles each.

Three of the articles selected for the PubMed Central dataset were missing from that set. After selecting the files and pre-processing them to extract the plain text, two files from the TREC Genomics collection were found to be empty. The corpus thus consists of 195 files containing content, 97 from the PubMed Central Open Access dataset and 98 from the TREC Genomics dataset. We then eliminated any files less than 1 kb (1024 bytes) in length, as those did not represent full text files. The remaining 163 files comprise a reference set which can be considered to be a balanced sample of both full text Open Access and traditional journal publications indexed in PubMed, and are not oriented on the topics relevant to mouse genomics on which CRAFT and TraJour are focused.

Computational methods

All the computations described here were implemented in Java within the UIMA (Unstructured Information Management Architecture) [22,23] framework.

Statistical methods

We have not performed significance testing of the statistical results provided in this paper as we are mostly interested in the qualitative differences that could impact text mining applications, and minor variations will always exist between any particular document corpora. This is a limitation of the approach.

Authors' contributions

KV conceived the lexical distribution measures, collected and pre-processed the corpora, and designed and carried out the KL divergence, frequency, and log likelihood experiments. KBC conceived, designed, and carried out the linguistic/syntactic experiments. LH contributed to the design of the experiments. KV, KBC, and LH analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The work of all three authors was supported by grants G08LM009639, R01LM009254, and R01LM008111 to Lawrence Hunter. We gratefully acknowledge the NIH scientific review author who originally suggested that we undertake this project and the reviewers of this paper for their thoughtful comments.

Contributor Information

Karin Verspoor, Email: karin.verspoor@ucdenver.edu.

K Bretonnel Cohen, Email: kevin.cohen@gmail.com.

Lawrence Hunter, Email: larry.hunter@ucdenver.edu.

References

- Verspoor K, Cohen KB, Mani I, Goertzel B. Linking natural language processing and biology: towards deeper biological literature analysis. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2006. Introduction to BioNLP'06; pp. iii–iv.http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W/W06/W06-3300.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke C, Valencia A. Can bibliographic pointers for known biological data be found automatically? Protein interactions as a case study. Comparative and Functional Genomics. 2001;2:196–206. doi: 10.1002/cfg.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PK, Perez-Iratxeta C, Bork P, Andrade MA. Information extraction from full text scientific articles: Where are the keywords? BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corney DP, Buxton BF, Langdon WB, Jones DT. BioRAT: extracting biological information from full-length papers. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3206–3213. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe L, Wilbur WJ. Tagging gene and protein names in full text articles. Proceedings of the ACL'02 workshop on Natural language processing in the biomedical domain. 2002. pp. 9–13.http://www.aclweb.org/anthology-new/W/W02/W02-0302.pdf

- Krallinger M, Leitner F, Rodriguez-Penagos C, Valencia A. Overview of the protein-protein interaction annotation extraction task of BioCreative II. Genome Biology. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s2-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh W, Voorhees E. TREC genomics special issue overview. Information Retrieval. 2008;12:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10791-008-9076-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The PubMed Central Open Access subset http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/about/openftlist.html

- Swan A, Brown S. Authors and open access publishing. Learned Publishing. 2004;17:219–224. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/alpsp/lp/2004/00000017/00000003/art00007 [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. Citation Advantage of Open Access Articles. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus MP, Marcinkiewicz MA, Santorini B. Building a large annotated corpus of English: the Penn Treebank. Computational Linguistics. 1993;19:313–330. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/J/J93/J93-2004.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Palmer M, Kingsbury P, Gildea D. The Proposition Bank: an annotated corpus of semantic roles. Computational Linguistics. 2005;31:71–106. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/J/J05/J05-1004.pdf [Google Scholar]

- TREC Genomics Track website http://ir.ohsu.edu/genomics/

- Knebel A, Morrice N, Cohen P. A novel method to identify protein kinase substrates: eEF2 kinase is phosphorylated and inhibited by SAPK4/p38 delta. The EMBO Journal. 2001;20:4360–4369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran K, Grainger R. Expression of activated MAP kinase in Xenopus laevis embryos: Evaluating the roles of FGF and other signaling pathways in early induction and patterning. Developmental Biology. 2000;228:41–56. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen KB, Palmer M, Hunter L. Nominalization and alternations in biomedical language. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biber D, Johansson S, Leech G, Conrad S, Finegan E. Longman grammar of spoken and written English Pearson. 1999.

- Kullback S, Leibler RA. On information and sufficiency. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1951;22:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. Accurate methods for the statistics of surprise and coincidence. Computational Linguistics. 1993;19:61–74. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology-new/J/J93/J93-1003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rayson P, Garside R. Comparing corpora using frequency profiling. Proceedings of the Workshop on Comparing Corpora, held in conjunction ACL 2000 October 2000, Hong Kong. 2000. pp. 1–6.http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W/W00/W00-0901.pdf

- Mouse Genome Institute's Gene Ontology annotation file http://cvsweb.geneontology.org/cgi-bin/cvsweb.cgi/go/gene-associations/gene_association.mgi.gz?rev=HEAD

- Ferrucci D, Lally A. Building an example application with the unstructured information management architecture. IBM Systems Journal. 2004;43:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- The Unstructured Information Management Architecture http://incubator.apache.org/uima