Abstract

The insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system regulates fetal and placental growth and development. In maternal diabetes, components of this system including insulin, IGF1, IGF2 and various IGF-binding proteins are deregulated in the maternal or fetal circulation, or in the placenta. The placenta expresses considerable amounts of insulin and IGF1 receptors at distinct locations on both placental surfaces. This makes the insulin and the IGF1 receptor accessible to fetal and/or maternal insulin, IGF1 and IGF2. Unlike the receptor for IGF1, the insulin receptor undergoes a gestational change in expression site from the trophoblast at the beginning of pregnancy to the endothelium at term. Insulin and IGFs are implicated in the receptor-mediated regulation of placental growth and transport, trophoblast invasion and placental angiogenesis. The dysregulation of the growth factors and their receptors may be involved in placental and fetal changes observed in diabetes, i.e. enhanced placental and fetal growth, placental hypervascularization and higher levels of fetal plasma amino acids.

Keywords: insulin, insulin-like growth factors, placenta, diabetes

Introduction

The placenta is a fetal organ located at the interface between the maternal and fetal circulation, fulfilling a spectrum of fundamental functions for pregnancy. Most central is the supply of nutrients and oxygen to the fetus and the production of a range of hormones and growth factors that, when released, may affect mother or fetus or both. In addition, placental processes may be controlled in a paracrine or autocrine fashion. Conversely, hormones, growth factors and substrate present in the maternal and the fetal circulation may tightly regulate placental development. Notably the insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system, i.e. insulin, IGF1, IGF2 and the IGF-binding proteins IGFBP1 and IGFBP3, are implicated in the regulation of fetal and placental growth and development. Such actions are mediated through their receptors, i.e. insulin and IGF1 receptors, which are expressed on distinct placental surfaces. Hence, dysregulation of insulin and IGFs may have profound effects on placenta and fetus.

The insulin/IGF system

The peptide hormones insulin, IGF1 and IGF2 mediate a variety of metabolic and mitogenic effects by binding to their specific receptor tyrosine kinases present on the surface of target tissues and cells. Because of their considerable structural homology, a distinct overlap exists in binding affinity between receptors on the one hand and insulin and IGFs on the other hand. However, at physiological concentrations, insulin and IGF1 exclusively bind to their cognate receptors, i.e. the insulin receptor (IR) and the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R), respectively. In contrast, IGF2 binds to the IGF1R and, in particular in embryonic and cancer tissues and cells, to an IR isoform that lacks exon 11 and is therefore denoted as IR 11– (Frasca et al. 1999). The affinity of IGF2 to IR 11– is only slightly lower than that of insulin (EC50 of 0.9 vs. 0.2 nm), whereas IGF1 binding to IR 11– has no physiological relevance (EC50 > 30.0 nm). The binding affinity of IGF2 to IGF1R is nearly comparable to that of IGF1 (EC50 0.6 vs. 0.2 nm), whereas insulin weakly binds (EC50 > 30.0 nm) (Pandini et al. 2002).

Placental IGF1 and IGF2 expression

IGF1 and IGF2 are important growth factors in fetal development. Both are synthesized in placenta and fetus with a considerable overlap in the location of both IGFs in the various placental cell types, in particular in the mesenchymal cells such as macrophages and endothelial cells, with little change throughout gestation. However, there is a clear difference and developmental change in the trophoblast compartment. Whereas IGF1 is present in syncytiotrophoblast and cytotrophoblast at all stages in gestation, IGF2 is not found in the syncytiotrophoblasts. Its expression in the villous and extravillous cytotrophoblasts in the first trimester becomes undetectable at term (Hill et al. 1993; Thomsen et al. 1997; Birnbacher et al. 1998; Han and Carter, 2000; Dalcik et al. 2001). It is unclear if the placenta-derived IGFs serve local purposes by paracrine or autocrine regulation, or if they are secreted into the maternal or fetal circulation.

IGFBPs

IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs) are further players in the IGF system. They are key modulators of the ligand–receptor interaction. The six human IGFBPs described so far circulate in the plasma and bind IGFs with a higher affinity than the receptors, thereby sequestering them from receptor binding (Hwa et al. 1999; Allan et al. 2001; Denley et al. 2005). This interaction facilitates endocrine IGF transport and prolongs the half-life of circulating IGFBP-bound IGFs (Hwa et al. 1999; Denley et al. 2005). In addition, IGFBPs can be associated with cell membranes or extracellular matrix. This allows them to maintain a local pool of IGFs. Because of similar affinities of IGFs for cell- or membrane-bound IGFBPs and for their receptors, the balance in the amount of both will be the main determinant of the prevailing binding site of IGFs (Han & Carter, 2000). Post-translational IGFBP modification by phosphorylation, glycosylation and specific proteolysis (Clemmons, 1998) can further modulate IGF binding. Phosphorylation and proteolysis are altered during pregnancy, resulting in a preponderance of IGFBPs with lowered affinities towards IGFs, thus increasing system-wide IGF bioavailability (Forbes & Westwood, 2008). In nonpregnant women, the majority of IGF1 is part of a ternary complex together with IGFBP3 and acid-labile subunit (Forbes & Westwood, 2008). The serum of pregnant women contains the placenta-derived IGFBP3 protease (Deal, 1992). It cleaves IGFBP3 into smaller fragments with lower affinities for IGFs, rendering IGFs available for binding to their receptors in mother and placenta (Giudice et al. 1990; Hossenlopp et al. 1990; Davenport et al. 1992). Placental alkaline phosphatase dephosphorylates serum IGFBP1 in pregnant women, reducing its affinity for IGF1 (Westwood et al. 1994), whereas IGFBP1 affinity for IGF2 remains unchanged. IGF2 binding to IGFBP1 is modulated by proteolytic cleavage of non-phosphorylated IGFBP1 by matrix metalloproteases MMP3 and MMP9 at the maternal–fetal interface (Coppock et al. 2004).

Decidual cells of the basal plate region express mRNA of all six IGFBPs in the second and third trimester, with IGFBP1 being the most abundant. In the placenta, IGFBP3 is expressed in the extravillous cytotrophoblasts (Hamilton et al. 1998). In maternal Type 1 diabetes (T1D), IGFBP3 mRNA is increased (Liu et al. 1996). Maternal serum and cord blood levels of IGFBP1 and -3 are altered in pregnancies complicated by diabetes. Studies examining IGFBP1 concentrations in offspring from T1D or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) mothers produced inconsistent results, with either elevated (Yan-Jun et al. 1996; Lindsay et al. 2007) or decreased (Culler et al. 1996; Lindsay et al. 2007) levels. An association between maternal diabetes and cord IGFBP1 phosphorylation state has been discussed as well (Loukovaara et al. 2005b). In the cord blood, increased IGFBP3 levels in pregnancies complicated by T1D correlate with IGF1 levels and the incidence of macrosomia (Nelson et al. 2008). This is consistent with the observation that IGF1 and IGFBP3 levels directly correlate with birth weight both in the healthy and in the diseased state (Osorio et al. 1996; Ong et al. 2004; Nelson et al. 2008).

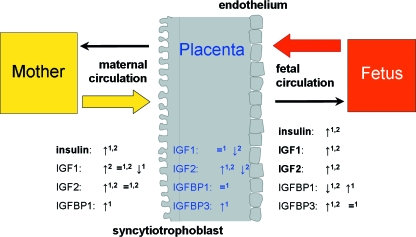

Diabetes in pregnancy and the insulin/IGF system

The placenta shows several alterations in maternal diabetes, and the insulin/IGF system has been implicated in several of these (Desoye & Shafrir, 1996; Desoye & Myatt, 2004; Desoye & Hauguel-de Mouzon, 2007; Desoye et al. 2008). GDM and T1D are characterized by dysregulation of various factors in the maternal, but also in the fetal, circulation, and in the placenta. These include components of the insulin/IGF system, i.e. insulin, IGF1, IGF2 and the IGF-binding proteins IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The placenta is exposed to metabolites and hormones of mother and fetus. Diabetes (T1D and GDM)-associated changes in levels of insulin, IGF1, IGF2, IGFBP1, IGFBP3 in maternal and fetal blood and in the placenta may influence placental function. Higher (↑), lower (↓) or similar (=) levels in T1D (1) or GDM (2) compared to normal pregnancies are indicated and taken from available references (Bhaumick et al. 1986; Desoye et al. 1992; Gelato et al. 1993; Hughes et al. 1995; Liu et al. 1996; Roth et al. 1996; Yan-Jun et al. 1996; Gibson et al. 1999; Homko et al. 2001; Lindsay et al. 2003, 2007; Radaelli et al. 2003; Loukovaara et al. 2005a; Westgate et al. 2006). Factors are printed in bold if the regulation in T1D and GDM is similar.

The placenta is richly endowed with IR and IGF1R, and serves as the tissue of origin for isolation of the receptor proteins. Both receptors are located on distinct placental surfaces, thus enabling maternal and/or fetal insulin, IGF1 and IGF2 to affect placental function and development. Therefore, in a pregnancy complicated by diabetes, altered insulin, IGF and IGFBP levels are most likely to influence placental cells in a manner different from normal pregnancies. These changes in the circulating levels of the growth factors may be superimposed by additional alterations in other components of the system such as IGFBPs, receptor expression, receptor activation and signalling.

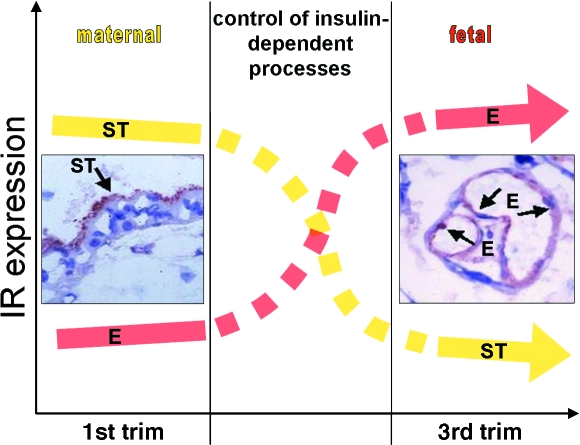

IR expression in the placenta

IR and IGF1R expression in the placenta is more complicated and restricted to special areas than has long been thought. Their location varies with gestational age. IR is expressed in a spatio-temporal manner. In the first trimester of pregnancy, IRs are predominantly expressed on the microvillous membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast, directed to the maternal circulation and, hence, maternal insulin. Some IRs are also present in the villous cytotrophoblasts. In contrast, IRs at term are mainly expressed on the placental endothelium directed to the fetal blood. Therefore, IR expression shifts throughout pregnancy from the surface facing the maternal circulation to that facing the fetal circulation (Desoye et al. 1994, 1997; Hiden et al. 2006). Tissue-resident macrophages (Hofbauer cells) also express IR.

The spatio-temporal change in receptor expression is paralleled by a change in total receptor activation, which results in accompanying changes in intracellular downstream effect as identified by insulin-induced gene expression. In isolated primary first trimester trophoblasts with high levels of IR, insulin altered the expression of 236 genes, whereas in primary term trophoblasts with lower IR levels, the effect of insulin expression was minimal (six regulated genes). At that time in gestation most IR are expressed on the placental endothelium, which readily responds to insulin stimulation (146 regulated genes). Hence, the shift in IR expression from the trophoblast to the endothelium represents also a shift in regulation of insulin effects from the mother to the fetus (Fig. 2) (Hiden et al. 2006).

Fig. 2.

The spatio-temporal change in placental insulin receptor (IR) expression suggests a shift in regulation of placental insulin effects from mother to fetus. In the first trimester, IRs are predominantly expressed on the syncytiotrophoblast (ST) facing the maternal circulation, whereas at term the placental endothelial cells (EC) facing the fetal circulation are the main expression site. The x-axis represents the amount of IR expression by visual inspection and the y-axis displays the course of gestation. Photographs of immunohistochemical stainings for the IR in first trimester (left) vs. term placental tissue (right) within the diagram are taken from Desoye et al. 1994 with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media.

Placental insulin effects

The impact of insulin on first trimester trophoblasts has not been studied beyond the general effect on gene expression (cf. above) in great detail. Results include effects on transport processes such as stimulation of deoxy-d-glucose uptake (Kniss et al. 1994) and α-isoaminobutyric acid (AIB) uptake (Guyda, 1991), but no effect on amino acid transport system A (Kniss et al. 1994) and O-methyl-glucose-uptake (Guyda, 1991). Despite the limited amount of data, two publications compare insulin effects on the trophoblasts between the first trimester and at term. Insulin inhibits hCG secretion in the first trimester, but not in term placental explants (Barnea et al. 1993). Moreover, insulin stimulates expression of the membrane-type matrix-metalloproteinase 1 (MT1-MMP, also MMP 14) (Hiden et al. 2008), a key regulator of cell invasion, migration and tissue remodelling. In vivo, these data are reflected by the correlation of MT1-MMP expression in the first trimester placental with maternal insulin in T1D, indicating that morphological and functional placental changes in pre-gestational diabetes may have their origin already in early pregnancy.

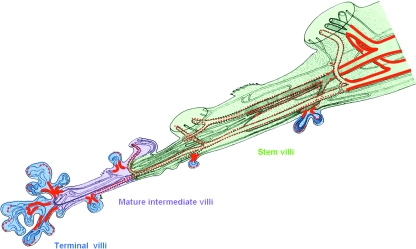

At term, the majority of placental IRs is located on the placental endothelium. A more detailed analysis of IR expression revealed that IRs are present particularly on the sites of villous and, hence, vascular branching (Fig. 3). The location of IRs correlates with staining for Ki-67, a cell-cycle dependent protein that is present in cells throughout the entire cell cycle, but not in resting cells (Desoye et al. 1997). The location of IRs at sites of proliferation suggests insulin involvement in vascular growth. This hypothesis is consistent with in situ data showing enhanced branching angiogenesis in GDM (Jirkovska et al. 2002), a condition accompanied by elevated fetal insulin levels as a result of maternal, and hence fetal, hyperglycaemia (Westgate et al. 2006). Therefore, elevated fetal insulin levels may stimulate endothelial cell proliferation and vascular branching by binding to IR present on the sites of villus ramification.

Fig. 3.

Location of insulin receptors (IR) in endothelium along the vascular tree in the human term placenta. Strong IR staining (thick red line) was restricted to arteries and veins of big stem villi and to capillaries at the site of branching of terminal villi from mature intermediate villi. Moderate IR staining (dotted red line) was found in arteries and veins of smaller stem villi. The sinusoids in terminal villi were also focally labelled. All other capillaries, arterioles and venules as well as the umbilical cord vessels were weakly stained if at all. Modified according to data in Desoye et al. (1994, 1997) from Fig. 4 published in Leiser et al. (1985) with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media.

The regulatory pathways of insulin-induced angiogenesis have been investigated in human umbilical venous endothelial cells (HUVEC) (Treins et al. 2002). Insulin activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) that further activates hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1). HIF-1 up-regulates expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), a well-known inducer of angiogenesis. VEGFR2, the most important receptor for VEGF, is abundantly expressed on the placental vasculature, especially on the arterial endothelial cells (Lang et al. 2008). It remains to be determined whether the above mechanism is operative in the human placenta. Human endothelial cells represent a heterogeneous cell type with significant differences among vascular beds (Aird, 2007) and pathways shown in one endothelial cell type are not necessarily the same for others.

Recent data suggest an effect of insulin on placental vascular function by altering expression of the endothelial junctional protein β-catenin (Lucas et al. 2008). These results of perfusion experiments may explain the in vivo findings in GDM with reduced levels of β-catenin in the placenta at term (Leach et al. 2004). Impaired expression of β-catenin results in increased vascular leakage and may ultimately lead to altered vascular integrity.

The most prominent function of insulin is the regulation and modulation of metabolic processes. Insulin also exerts its metabolic effects in the placenta. Differently from trophoblasts at term (Schmon et al. 1991), glycogen synthesis is up-regulated by insulin in endothelial cells (Desoye & Hauguel-de Mouzon, 2007). This is paralleled by the observation of increased glycogen deposit around the placental vessels in maternal diabetes (Jones & Desoye, 1993). The function of these glycogen deposits remains to be determined, although the supply of energy to cover local demands of endothelial cells and pericytes to perform transport and contractile functions may be hypothesized. Insulin was also reported to stimulate lipid deposition and the formation of lipid droplets in term trophoblasts (Elchalal et al. 2005). This may explain the increase in phospholipid and triglyceride content in placentas from GDM and T1D pregnancies (Diamant et al. 1982).

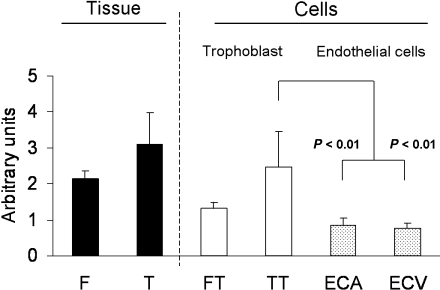

Novel data – IGF1R expression in the placenta

IGF1R mRNA is present in first trimester and term placental tissue. At the end of gestation, IGF1 expression is higher in the trophoblasts than in endothelial cells, independent of their venous or arterial origin (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Relative IGF1R mRNA abundance in first trimester (F) and term (T) placental tissue, isolated first trimester (FT) and term trophoblasts (TT), and term arterial (ECA) and venous (ECV) endothelial cells. Expression of mRNA was measured by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (mean ± SEM; n = 5). Total RNA was isolated using TriReagent (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). Primers were designed so as to include splicing sites within the amplicon. The ribosomal protein L30 (RPL30) was used as an internal control because of its stable expression within the investigated placental cell types and tissues. Sequences of forward (for) and reverse (rev) primers: RPL30 for: CCTAAGGCAGGAAGATGGTG; RPL30 rev: CAGTCTGTTCTGGCATGCTT; IGF1R for: GGATGCGGTGTCCAATAACT; IGF1R rev: TGGCAGCACTCATTGTTCTC. For RPL30, 25 cycles and for IGF1R, 29 cycles were used for the amplification of 100 ng RNA at an annealing temperature of 60 °C. PCR-products were electrophoresed on 2.5% agarose gels, documented with the Eagle-Eye™ system (Stratagene, CA, USA) and quantified using AlphaDigiDoc 1000 (Alpha Innotech, CA, USA) software. The optimal RT-PCR cycle number for RPL30 and IGF1R was determined to lie within the linear range of the amplification in preliminary experiments (not shown). Mann–Whitney rank sum test (SigmaPlot10; Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA, USA) was used for statistical data analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The location of IGF1R as analysed by immunohisto-chemistry differs from that of IR. In the first trimester a prominent staining of IGF1R was observed in the proliferating cytotrophoblasts especially of the cell columns, which is in line with IGF1 effects on cytotrophoblast proliferation (Maruo et al. 1995; Hills et al. 2004). At term of gestation sites with moderate IGF1R expression include tissue-resident macrophages and endothelial cells. The main IGF1R expression site, however, is the basal membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast and the villous cytotrophoblasts (Fig. 5). This raises the question of distinct functions that may be coupled with the special location of IGF1R.

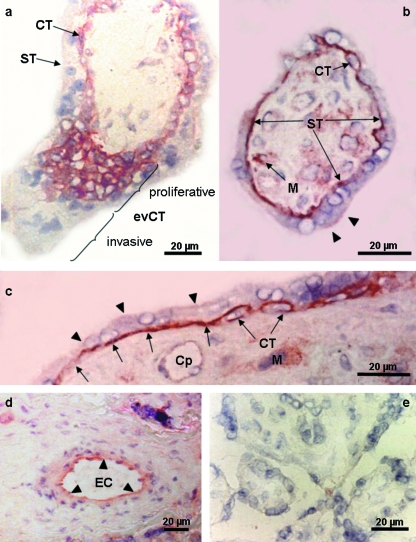

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical localization of IGF1R in the human placenta of the first trimester (a) and at term of gestation (b–d). (a) In the first trimester (week 10 post menstruation) the plasma membrane of the villous cytotrophoblast (CT) was strongly stained as was the basal membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast (ST); other cells in the stroma did not immunoreact. Among the extravillous cytotrophoblast (evCT) only three to five proximal cellular layers of the cell columns, representing the proliferative phenotype, were strongly labelled, whereas the more distal invasive evCTs were unlabelled. (b–d) Cross-sections of a mature intermediate villus (b) and stem villus (c,d). The basal plasma membrane of the ST and the villous CT are strongly and continuously stained. The microvillous ST membrane is weakly and discontinuously stained (arrowheads). Tissue macrophages (M) are also strongly labelled. Endothelial cells in capillaries (Cp in c) are weakly and discontinuously labelled, whereas in larger calibre vessels they are moderately and continuously stained (d). (e) Negative control by omission of primary antibody. Magnification bars represent 20 µm. To allow easier identification of key structures the surrounding villi were erased in (a–c) using photoshop software. The immunohistochemical staining method essentially followed an established protocol (Desoye et al. 1994). Labelling was detected with the LSAB-kit detection system (Dako, Vienna, Austria). The monoclonal antibody against the IGF1R (clone αIR3; dilution 1 : 10; Oncogene Science Inc, Cambridge, MA, USA) immunoprecipitates the α- and β-subunits of human IGF1R. The antibody blocks IGF1 binding to its receptor without affecting insulin receptors (Kull et al. 1983).

The tight junctions of endothelial cells in the placental vasculature do not seal the endothelium. The paracellular clefts between the endothelial cells allow the transfer of gases such as oxygen and small nutrients across the endothelial layer. This transfer is not unidirectional and may occur also from the fetal circulation into the placenta and even into the maternal circulation. IGF1R located on the basal syncytiotrophoblast membrane as well as on the villous cytotrophoblasts can, therefore, bind IGF1 and IGF2 that has been taken up from the fetal circulation. In addition, paracrine effects are possible. Because some IGF1Rs are also present on the microvillous syncytiotrophoblast membrane, both maternal and fetal IGF1 will affect the trophoblast compartment. In association with maternal diabetes, fetal IGF1 and IGF2 levels are elevated. Hence, in diabetes, fetal IGF1 may over-stimulate IGF1-dependent processes, although this may be counteracted or compensated by the lower placental IGF1 in GDM (Radaelli et al. 2003) (Fig. 1).

Placental IGF effects

Various effects of IGF1 and IGF2 on isolated trophoblasts have been described. A key process regulated by IGF1 and IGF2 throughout pregnancy is amino acid transport (Guyda, 1991; Bloxam et al. 1994; Karl, 1995), in line with their role as important growth factors for the fetus. The up-regulation of placental amino-acid transporters resulting from increased IGF1 and IGF2 is paralleled in vivo by elevated fetal amino acid levels in GDM (Cetin et al. 2005).

In vitro IGFs regulate proliferation and survival of cytotrophoblasts in a human first trimester explant model (Forbes et al. 2008). Both effects are mediated via two different signalling pathways, i.e. proliferation is stimulated via the MAPK pathway whereas rescue from apoptosis is signalled through the PI3 K pathway. These effects were induced by IGFs present in the culture medium and, therefore, a mechanism must be in place to either allow IGF passage across the syncytiotrophoblast or to deliver a signal across the syncytiotrophoblast to the cytotrophoblasts underneath. In vivo the location of IGF1R would also allow fetal and/or placentally derived IGFs to regulate the life cycle of trophoblasts in the first trimester.

In addition, in first trimester trophoblasts IGF1 and IGF2 stimulate various processes that are involved in trophoblast invasion into the maternal uterus such as invasiveness (Hamilton et al. 1998), migration (Irving and Lala, 1995; Kabir-Salmani et al. 2004), lamellipodia formation (Kabir-Salmani et al. 2002), MMP2 production, proliferation (Hills et al. 2004; Forbes et al. 2008), and MT1-MMP expression (Hiden et al. 2008).

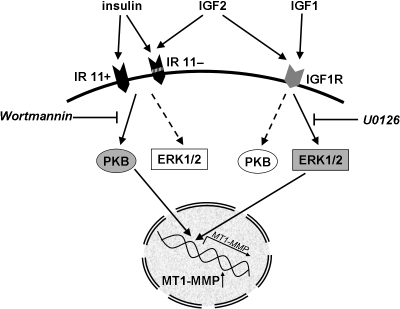

Thus, MT1-MMP is regulated by all three ligands of the insulin/IGF family. However, the intracellular signalling pathways differ, suggesting that different receptors are also activated. Inhibition of the main signalling pathways of IR and IGF1R, i.e. the PI3K/PKB pathway, which in general mediates the metabolic effects, and the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway as main signalling pathway for proliferation regulation, indicated that the IR induces MT1-MMP expression via PKB, whereas the IGF1R uses the ERK1/2 pathway. IGF2 requires and uses both pathways consonant with its ability to bind to both IGF1R and the IR 11– isoform (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

MT1-MMP expression in first trimester trophoblasts is stimulated by insulin, IGF1 and IGF2 by different signalling pathways. Insulin signals via the two isoforms of the insulin receptor, i.e. IR 11+ and IR 11−. IGF1 binds to the IGF1R, whereas IGF2 binds to IGF1R as well as to IR 11−. The pathways activated by the receptor tyrosine kinases ultimately inducing MT1-MMP transcription differ. Insulin receptor signalling is inhibited by Wortmannin, which blocks the PI3K/PKB pathway. In contrast, IGF1R signalling is abolished by U0126, an inhibitor of the MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. The IGF2-induced up-regulation of MT1-MMP is inhibited by both compounds (Hiden et al. 2008).

So far, there has only been one study of the effect of maternal diabetes on the placenta in the first trimester (Hiden et al. 2008). It is unknown whether trophoblast invasion is affected by maternal diabetes. This can be suspected because of the higher incidence in pregestational diabetes of pregnancy problems with underlying invasion defects such as intrauterine growth restriction, pre-eclampsia and spontaneous abortions. However, currently no evidence is available indicating enhanced or abnormally deep placental invasion in diabetes.

Regulation of placental growth by fetal insulin and IGFs

Insulin and the IGFs have long been implicated in the regulation of fetal growth and fat accumulation. There is also a growing body of evidence from various studies to suggest either a direct or an indirect effect of these growth factors on placental growth. Based on histochemical and morphometric evidence, villous growth in the third trimester, when placental growth is predominantly characterized by mass expansion, is driven by capillary growth and proliferation (Kaufmann et al. 1988; Mayhew, 2002), suggesting a regulatory influence by fetal factors. Because of the diabetes-associated alterations in the fetal insulin/IGF system (see Fig. 1) these growth factors may contribute.

Owing to the prevalence of placental IR at the endothelium in the third trimester and in particular at sites of high proliferative activity (see Fig. 2) insulin was proposed as one of these growth factors (Desoye et al. 1994, 1997). This notion is supported by studies in primates, in which insulin infusion into the fetal circulation resulted in a higher placental weight (Susa et al. 1984). The correlation of cord blood insulin levels with placental weight in human lends further support to this (Godfrey et al. 1996). More direct evidence comes from manipulations by nature such as genetic variations or a lack of fetal pancreas. In offspring with mutations in the glucokinase gene, placental weight is reduced. Glucokinase serves as the pancreatic glucose sensor. Mutations may result in loss of function, in an impairment of insulin secretion and, hence, in lower levels of fetal insulin (Shields et al. 2008). Moreover, in a case of fetal pancreas agenesis, placental weight at week 36 was lower than normal (195 g), which was associated also with a lower birth weight (1350 g) (Lemons et al. 1979). Hence, reduction in fetal insulin levels or even absence of the fetal pancreas both resulted in lower placental weight, which concurs with the hypothesis of fetal insulin serving as a growth factor for the placenta.

The pronounced expression of IGF1 receptors on the basal plasma membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast and on the endothelial cells argues for fetal IGF1 as a regulator of placental processes yet to be identified. Control of placental growth may be one candidate effect, as deletion of the fetal IGF1 gene resulted in placental weight that was 1.3 SD below the mean (Woods et al. 1996). Mutations of the IGF1R are associated with profoundly lower fetal weights (Abuzzahab et al. 2003), whereas the presence of three copies of the IGF1R gene was associated with a heavier and longer neonate (Okubo et al. 2003). Unfortunately, no information is available on the effects of such aberrations on placental growth or weight. The surprisingly small effect of lack of fetal IGF1 on placental weight may be explained by the compensatory increase in the levels of fetal IGF2 (Woods et al. 1996), which is a strong determinant of placental growth/weight as can be seen in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. This pathology is characterized by a duplication of the fetal IGF2 gene and leads to massive placental overgrowth with little effect on the fetal weight (Shapiro et al. 1982; Takayama et al. 1986). Collectively, these isolated data argue for a predominant role of insulin and IGF2 with some contribution of fetal IGF1 in the control of placental growth.

Acknowledgments

The authors are gratefully indebted to Peter Kaufmann for his continuous interest and support of our work, for stimulating and helpful discussions on every aspect of placental structure and development and for the permission to use Fig. 3, which he modified for the purpose of the present article. Moreover, Peter Kaufmann strongly helped us with the preparation of Fig. 5 and interpretation of the findings.

The work was supported by grants 11964 and 12601 from the Jubileefund of the Austrian National Bank (OeNB).

References

- Abuzzahab MJ, Schneider A, Goddard A, et al. IGF-I receptor mutations resulting in intrauterine and postnatal growth retardation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2211–2222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circ Res. 2007;100:174–190. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan GJ, Flint DJ, Patel K. Insulin-like growth factor axis during embryonic development. Reproduction. 2001;122:31–39. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea ER, Neubrun D, Shurtz-Swirski R. Effect of insulin on human chorionic gonadotrophin secretion by placental explants. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:858–862. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumick B, Danilkewich AD, Bala RM. Insulin-like growth factors (IGF) I and II in diabetic pregnancy: suppression of normal pregnancy-induced rise of IGF-I. Diabetologia. 1986;29:792–797. doi: 10.1007/BF00873218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbacher R, Amann G, Breitschopf H, Lassmann H, Suchanek G, Heinz-Erian P. Cellular localization of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA in the human fetus and the placenta: detection with a digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probe and immunocytochemistry. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:614–620. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloxam DL, Bax BE, Bax CM. Epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor I differently influence the directional accumulation and transfer of 2-aminoisobutyrate (AIB) by human placental trophoblast in two-sided culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:922–929. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin I, DE Santis MS, Taricco E, et al. Maternal and fetal amino acid concentrations in normal pregnancies and in pregnancies with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons DR. Role of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in controlling IGF actions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;140:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppock HA, White A, Aplin JD, Westwood M. Matrix metalloprotease-3 and -9 proteolyze insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:438–443. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culler FL, Tung RF, Jansons RA, Mosier HD. Growth promoting peptides in diabetic and non-diabetic pregnancy: interactions with trophoblastic receptors and serum carrier proteins. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1996;9:21–29. doi: 10.1515/jpem.1996.9.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalcik H, Yardimoglu M, Vural B, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor in the placenta of intrauterine growth-retarded human fetuses. Acta Histochem. 2001;103:195–207. doi: 10.1078/0065-1281-00580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport ML, Pucilowska J, Clemmons DR, Lundblad R, Spencer JA, Underwood LE. Tissue-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 protease activity during rat pregnancy. Endocrinology. 1992;130:2505–2512. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.5.1374007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal C. Possible decidual origin of human IGFBP-3 protease activity during pregnancy. Proceedings of the 74th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, 1992.

- Denley A, Cosgrove LJ, Booker GW, Wallace JC, Forbes BE. Molecular interactions of the IGF system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:421–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. The human placenta in gestational diabetes mellitus. The insulin and cytokine network. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl. 2):S120–126. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Myatt L. The placenta. In: Reece EA, Coustan DR, Gabbe SG, editors. Diabetes in Women. Adolescence, Pregnancy and Menopause. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Williams; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Shafrir E. The human placenta in diabetic pregnancy. Diabetes Rev. 1996;4:70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Hofmann HH, Weiss PA. Insulin binding to trophoblast plasma membranes and placental glycogen content in well-controlled gestational diabetic women treated with diet or insulin, in well-controlled overt diabetic patients and in healthy control subjects. Diabetologia. 1992;35:45–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00400851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Hartmann M, Blaschitz A, et al. Insulin receptors in syncytiotrophoblast and fetal endothelium of human placenta. Immunohistochemical evidence for developmental changes in distribution pattern. Histochemistry. 1994;101:277–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00315915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Hartmann M, Jones CJ, et al. Location of insulin receptors in the placenta and its progenitor tissues. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:63–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970701/15)38:1/2<63::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G, Shafrir E, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. The placenta in diabetic pregnancy: placental transfer of nutrients. In: Hod M, Jovanovic L, Direnzo G-C, Deleiva A, Langer O, editors. Textbook Diabetes Pregnancy. 2nd edn. London: Informa Healthcare; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Diamant YZ, Metzger BE, Freinkel N, Shafrir E. Placental lipid and glycogen content in human and experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:5–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elchalal U, Schaiff WT, Smith SD, et al. Insulin and fatty acids regulate the expression of the fat droplet-associated protein adipophilin in primary human trophoblasts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1716–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes K, Westwood M. The IGF axis and placental function. A mini review. Horm Res. 2008;69:129–137. doi: 10.1159/000112585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes K, Westwood M, Baker PN, Aplin JD. Insulin-like growth factor I and II regulate the life cycle of trophoblast in the developing human placenta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1313–1322. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00035.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, et al. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3278–3288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelato MC, Rutherford C, San-Roman G, Shmoys S, Monheit A. The serum insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptor in normal and diabetic pregnancy. Metabol. 1993;42:1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90019-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JM, Westwood M, Lauszus FF, Klebe JG, Flyvbjerg A, White A. Phosphorylated insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 is increased in pregnant diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1999;48:321–326. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudice LC, Farrell EM, Pham H, Lamson G, Rosenfeld RG. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in maternal serum throughout gestation and in the puerperium: effects of a pregnancy-associated serum protease activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:806–816. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-4-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey KM, Hales CN, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Taylor KP. Relation of cord plasma concentrations of proinsulin, 32–33 split proinsulin, insulin and C-peptide to placental weight and the baby's size and proportions at birth. Early Hum Dev. 1996;46:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(96)01752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyda HJ. Metabolic effects of growth factors and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on cultured human placental cells of early and late gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72:718–723. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-3-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GS, Lysiak JJ, Han VK, Lala PK. Autocrine-paracrine regulation of human trophoblast invasiveness by insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II and IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-1. Exp Cell Res. 1998;244:147–156. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han VK, Carter AM. Spatial and temporal patterns of expression of messenger RNA for insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in the placenta of man and laboratory animals. Placenta. 2000;21:289–305. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiden U, Maier A, Bilban M, et al. Insulin control of placental gene expression shifts from mother to foetus over the course of pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2006;49:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiden U, Glitzner E, Ivanisevic M, et al. MT1-MMP expression in first-trimester placental tissue is upregulated in type 1 diabetes as a result of elevated insulin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels. Diabetes. 2008;57:150–157. doi: 10.2337/db07-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DJ, Clemmons DR, Riley SC, Bassett N, Challis JR. Immunohistochemical localization of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF binding proteins-1, -2 and -3 in human placenta and fetal membranes. Placenta. 1993;14:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(05)80244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills FA, Elder MG, Chard T, Sullivan MH. Regulation of human villous trophoblast by insulin-like growth factors and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1. J Endocrinol. 2004;183:487–496. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homko C, Sivan E, Chen X, Reece EA, Boden G. Insulin secretion during and after pregnancy in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:568–573. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossenlopp P, Segovia B, Lassarre C, Roghani M, Bredon M, Binoux M. Evidence of enzymatic degradation of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in the 150 K complex during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:797–805. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-4-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SC, Johnson MR, Heinrich G, Holly JM. Could abnormalities in insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins during pregnancy result in gestational diabetes? J Endocrinol. 1995;147:517–524. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1470517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa V, OH Y, Rosenfeld RG. The insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP) superfamily. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:761–787. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving JA, Lala PK. Functional role of cell surface integrins on human trophoblast cell migration: regulation by TGF-beta, IGF-II, and IGFBP-1. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:419–427. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirkovska M, Kubinova L, Janacek J, Moravcova M, Krejci V, Karen P. Topological properties and spatial organization of villous capillaries in normal and diabetic placentas. J Vasc Res. 2002;39:268–278. doi: 10.1159/000063692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CJ, Desoye G. Glycogen distribution in the capillaries of the placental villus in normal, overt and gestational diabetic pregnancy. Placenta. 1993;14:505–517. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(05)80204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir-Salmani M, Shiokawa S, Akimoto Y, et al. Characterization of morphological and cytoskeletal changes in trophoblast cells induced by insulin-like growth factor-I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5751–5759. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir-Salmani M, Shiokawa S, Akimoto Y, Sakai K, Iwashita M. The role of alpha(5)beta(1)-integrin in the IGF-I-induced migration of extravillous trophoblast cells during the process of implantation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:91–97. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl PI. Insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulates amino acid uptake by the cultured human placental trophoblast. J Cell Physiol. 1995;165:83–88. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Luckhardt M, Leiser R. Three-dimensional representation of the fetal vessel system in the human placenta. Trophoblast Res. 1988;3:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kniss DA, Shubert PJ, Zimmerman PD, Landon MB, Gabbe SG. Insulinlike growth factors. Their regulation of glucose and amino acid transport in placental trophoblasts isolated from first-trimester chorionic villi. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kull FC, Jr, Jacobs S, Su YF, Svoboda ME, Van Wyk JJ, Cuatrecasas P. Monoclonal antibodies to receptors for insulin and somatomedin-C. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6561–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Schweizer A, Hiden U, et al. Human fetal placental endothelial cells have a mature arterial and a juvenile venous phenotype with adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential. Differentiation. 2008;76:1031–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach L, Gray C, Staton S, et al. Vascular endothelial cadherin and beta-catenin in human fetoplacental vessels of pregnancies complicated by Type 1 diabetes: associations with angiogenesis and perturbed barrier function. Diabetologia. 2004;47:695–709. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser R, Luckhardt M, Kaufmann P, Winterhager E, Bruns U. The fetal vascularisation of term human placental villi. I. Peripheral stem villi. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1985;173:71–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00707305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons JA, Ridenour R, Orsini EN. Congenital absence of the pancreas and intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatrics. 1979;64:255–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RS, Walker JD, Halsall I, et al. Insulin and insulin propeptides at birth in offspring of diabetic mothers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1664–1671. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RS, Westgate JA, Beattie J, et al. Inverse changes in fetal insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and IGF binding protein-1 in association with higher birth weight in maternal diabetes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Tsushima T, Onoda N, et al. Expression of messenger RNA of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF binding proteins (IGFBP1–6) in placenta of normal and diabetic pregnancy. Endocr J. 1996;43(Suppl):S89–91. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.43.suppl_s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukovaara S, Immonen IJ, Koistinen R, et al. The insulin-like growth factor system and Type 1 diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy. J Diabetes Complications. 2005a;19:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukovaara S, Kaaja RJ, Koistinen RA. Cord serum insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 and -3: effect of maternal diabetes and relationships to fetal growth. Diabetes Metab. 2005b;31:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas J, Thomas R, Ikram A, Leach L. The effect of fetal hyperinsulinemia on human placental vascular function: Perfusion of fetal microvascular bed with high insulin results in increased vascular leakage and loss of junctional beta-catenin. Microcirculation. 2008 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Maruo T, Murata K, Matsuo H, Samoto T, Mochizuki M. Insulin-like growth factor-I as a local regulator of proliferation and differentiated function of the human trophoblast in early pregnancy. Early Pregnancy. 1995;1:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew TM. Fetoplacental angiogenesis during gestation is biphasic, longitudinal and occurs by proliferation and remodelling of vascular endothelial cells. Placenta. 2002;23:742–750. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(02)90865-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SM, Freeman DJ, Sattar N, Lindsay RS. Role of adiponectin in matching of fetal and placental weight in mothers with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1123–1125. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo Y, Siddle K, Firth H, et al. Cell proliferation activities on skin fibroblasts from a short child with absence of one copy of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF1R) gene and a tall child with three copies of the IGF1R gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5981–5988. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CY, Lao TT, Spencer K, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum level of placental growth factor in diabetic pregnancies. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio M, Torres J, Moya F, et al. Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF binding proteins-1, -2, and -3 in newborn serum: relationships to fetoplacental growth at term. Early Hum Dev. 1996;46:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(96)01737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandini G, Frasca F, Mineo R, Sciacca L, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. Insulin/insulin-like growth factor I hybrid receptors have different biological characteristics depending on the insulin receptor isoform involved. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39684–39695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli T, Varastehpour A, Catalano P, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Gestational diabetes induces placental genes for chronic stress and inflammatory pathways. Diabetes. 2003;52:2951–2958. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Abernathy MP, Lee WH, et al. Insulin-like growth factors I and II peptide and messenger RNA levels in macrosomic infants of diabetic pregnancies. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1996;3:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmon B, Hartmann M, Jones CJ, Desoye G. Insulin and glucose do not affect the glycogen content in isolated and cultured trophoblast cells of human term placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:888–893. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-4-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro LR, Duncan PA, Davidian MM, Singer N. The placenta in familial Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1982;18:203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields BM, Spyer G, Slingerland AS, et al. Mutations in the glucokinase gene of the fetus result in reduced placental weight. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:753–757. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susa JB, Neave C, Sehgal P, Singer DB, Zeller WP, Schwartz R. Chronic hyperinsulinemia in the fetal rhesus monkey. Effects of physiologic hyperinsulinemia on fetal growth and composition. Diabetes. 1984;33:656–660. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Watanabe T, Akiyama Y, et al. Reproductive toxicity of ofloxacin. Arzneimittelforschung. 1986;36:1244–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen BM, Clausen HV, Larsen LG, Nurnberg L, Ottesen B, Thomsen HK. Patterns in expression of insulin-like growth factor-II and of proliferative activity in the normal human first and third trimester placenta demonstrated by non-isotopic in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical staining for MIB-1. Placenta. 1997;18:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)90086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Semenza GL, Van Obberghen E. Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27975–27981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204152200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgate JA, Lindsay RS, Beattie J, et al. Hyperinsulinemia in cord blood in mothers with type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus in New Zealand. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1345–1350. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood M, Gibson JM, Davies AJ, Young RJ, White A. The phosphorylation pattern of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 in normal plasma is different from that in amniotic fluid and changes during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1735–1741. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.6.7527409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods KA, Camacho-Hubner C, Savage MO, Clark AJ. Intrauterine growth retardation and postnatal growth failure associated with deletion of the insulin-like growth factor I gene. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1363–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610313351805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan-Jun L, Tsushima T, Minei S, et al. Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP-1, -2 and -3) in diabetic pregnancy: relationship to macrosomia. Endocr J. 1996;43:221–231. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.43.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]