Abstract

We review recent work on DNA-linked gold nanoparticle assemblies. The synthesis, properties, and phase behavior of such DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies are described. These nanoparticle assemblies have strong optical extinction in the ultraviolet and visible light regions; hence, the technique is used to study the kinetics and phase transitions of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. The melting transition of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies shows unusual trends compared to those of free DNA. The phase transitions are influenced by many parameters, such as nanoparticle size, DNA sequence, DNA grafting density, DNA linker length, interparticle distance, base pairing defects, and disorders. The physics of the DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies can be understood in terms of the phase behavior of complex fluids, with the colloidal gold interaction potential dominated by DNA hybridization energies.

Keywords: DNA, Nanoparticle, Phase transition, Disorder

Introduction

DNA plays a crucial role in all living organisms because it is the key molecule responsible for storage, duplication, and realization of genetic information [1]. Since the discovery of DNA’s double-helix structure in 1953 [2], numerous disciplines have embraced this biomolecule –from biology, medicine, materials, chemistry, to physics. In particular, with recent rapid development in nanotechnology, the versatile DNA molecule has found many applications ranging from biology and medicine to biotechnology and computing.

DNA has shown a great potential in self-assembly of nanostructures and devices. A variety of DNA-based nanostructures have been successfully synthesized during the past several years, such as DNA-linked metal nanoparticles [3–6], semiconductor particles [7–10], fullerene molecules [11], DNA-directed nanowires [12–14], and DNA-functionalized carbon nanotubes [15–20]. The unique physical properties of nanoscale solids (dots, nanowires, nanotubes) in conjunction with the remarkable recognition capabilities of DNA molecules could lead to the development of miniaturization of biological electronics and optical devices to include probes and sensors. Such devices may exhibit advantages over existing technology not only in size but also in performance. There have been plenty of good examples that utilize nanostructured materials conjugated with DNA molecules as novel biosensors [21–31].

DNA-linked gold nanoparticle assembly is a prototype of DNA-based nanostructures (see Fig. 1). The optical properties and phase transition of this system have attracted considerable interest because understanding of these properties would provide essential information about DNA-based nanotechnology as well as phase transitions in colloidal systems [32]. These structures are assembled using individual strands of DNA modified at their ends with an alkanethiol group, creating a chemical affinity for gold nanoparticles. Adding a complementary linker DNA sequence induces hybridization of DNA into a double helix, resulting in self-assembly of gold nanoparticles and a visual change in the optical properties of the solution. The color change brought about by aggregation has generated the possibility that DNA-linked nanoparticles may become a tool for DNA detection technology, which has numerous applications in medical research, including diagnosis of genetic diseases, RNA profiling, and biodefense [33–37]. Furthermore, these assemblies may also be used as an alternative technology to genechips [38] and single-molecule sequencing [39]. It has been shown that this method can detect certain single-base defects, such as a one-base mismatch or deletion [40].

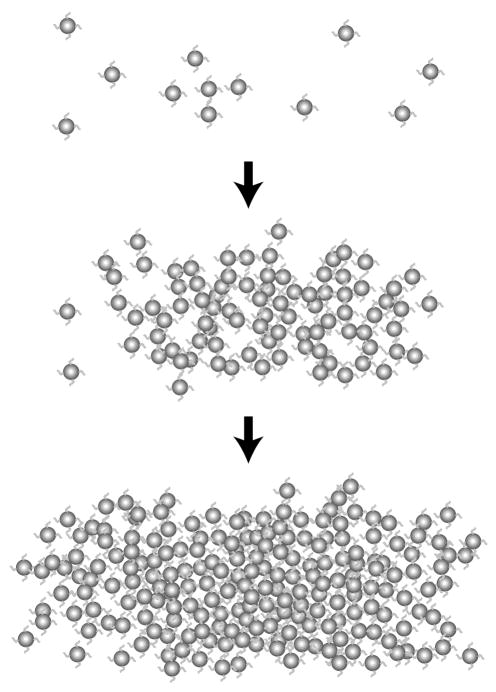

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the aggregation and network formation of DNA-linked gold nanoparticles in solution. Gold nanoparticles are dispersed in solution and self-assemble when linker DNA is introduced. The particles aggregate into amorphous, gel-like structures. Reprint from Kiang [41]

Moreover, it is becoming clear that DNA confined to surfaces behave differently from free DNA in solution. Experiments have so far demonstrated that phase transitions for this system are unique, making DNA-linked nanoparticles a new class of complex fluids [41–44]. These assemblies are formed from the non-covalent hydrogen bonding between single strands of DNA, making the aggregation process reversible. Unlike the broad melting transition for double- to single- stranded DNA, DNA-linked nanoparticle networks display a sharp transition from aggregated to diffuse phase, proving that melting of these assemblies is not simply a DNA duplex denaturation process. Therefore, DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies provide a model system for the study of surface-attached DNA melting and colloidal phase transition.

In this article, we review recent work on DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. The paper is organized as follows: The second section (“Synthesis of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies”) describes the methods of synthesizing DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. The third section (“Optical Properties”) introduces the basic optical properties of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. The fourth and fifth sections (“Effects of external variables on the phase transition” and “Effects of disorder and defects on the phase transition”) summarize the effects of various external parameters and disorders on the phase transition. The last section contains concluding remarks (“Conclusions”).

Synthesis Of Dna-Gold Nanoparticle Assemblies

In 1996, Mirkin and coworkers first described a method of assembling colloidal gold nanoparticles into macroscopic aggregates using DNA as linking elements [3]. This built up a base for the study of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. As illustrated in Fig. 2 (top), the preparation of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies usually involves two batches of gold particles that are functionalized, using thiol groups, with non-complementary DNA (probe) of sequences a and b, respectively. When another DNA (linker) with a complementary sequence a′b′ is introduced, the gold nanoparticles self-assemble into aggregates because of the hydrogen binding between DNA bases. This process can be reversed when the temperature is raised, which results in breaking of the hydrogen bonds, i.e. melting of the DNA double helix.

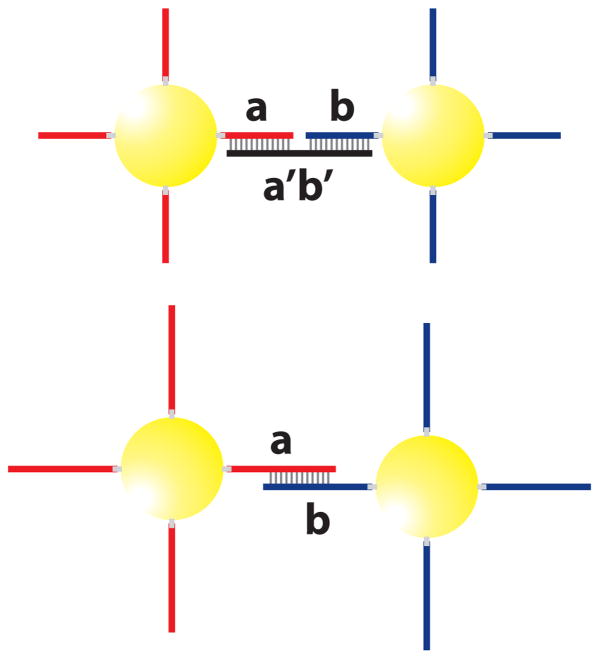

Fig. 2.

Top: Schematic of DNA-linked nanoparticle assembly formed from two non-complementary nanoparticle probes and a linker DNA sequence that is complementary to both probes. Bottom: An alternative method of DNA-nanoparticle network synthesis, in which no linker DNA is used, and the DNA attached to the gold particles are complementary to one another.

In addition to the linker method, the DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies can also be synthesized without a linker DNA [45]. Figure 2 (bottom) shows two batches of gold particles functionalized with DNA oligonucleotides with sequences a and b, respectively. Sequence a is complementary or partly complementary to sequence b. When these two batches are mixed, the direct hybridization between a and b results in self-assembly of gold particles that eventually form aggregates. Because of the molecular recognition properties associated with the DNA interconnects, the above strategies allow one to control interparticle distance, strength of the particle interconnects, and size and chemical identity of the particles in the targeted macroscopic structure.

Optical Properties

It is well known that DNA bases have a strong optical absorption in the ultraviolet region (~260 nm). Meanwhile, the surface plasmon of gold nanoparticles causes a strong extinction in the visible light region (~520 nm). The extinction coefficient of a collection of gold particles is dependent on the size of the aggregates. The change in the extinction reflects the aggregation of the gold nanoparticles. Thus, optical absorption spectroscopy is used to study the melting properties of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. The kinetics of aggregation of DNA-linked gold nanoparticles is studied by measuring the optical absorption spectrum as a function of time at room temperature [41], as illustrated in Fig. 3 (top).

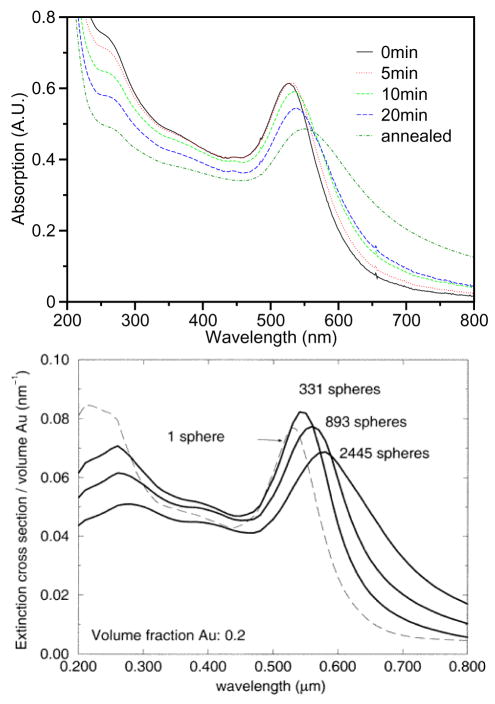

Fig. 3.

Top: Optical absorption spectra during DNA-linked gold nanoparticle aggregation. Adding linker DNA to the system results in a shift and broadening of the gold surface plasmon peak at 520 nm. Reprint from Kiang [41]. Bottom: Calculated extinction spectra for DNA-linked metal nanosphere assemblies of increasing size. The match between theory and experiments helps us to understand the particle aggregation process. Reprint from Lazarides and Schatz [46].

Upon adding linker DNA, the DNA hybridization leads to aggregation of gold nanoparticles, as demonstrated in the gold surface plasmon peak (520 nm) shift of the DNA-modified gold nanoparticles [46,47]. The calculated spectra of the assembly process is shown in Fig. 3 (bottom). The assembly starts with the wavelength shift of the plasmon band, followed by broadening and more shifting of the peak as hybridization continues. These results indicate that initial aggregation is accompanied by increasing volume fraction, followed by increasing network size [41,42].

Optical absorption spectrum is also used to monitor the melting properties of the DNA-gold aggregates. Due to hypochromism, which results from unpaired DNA bases absorbing light more efficiently than paired DNA bases, the absorption intensity at 260 nm increases as a result of DNA melting. Meanwhile, the melting also results in sharp changes in the gold nanoparticle extinction coefficient due to the dissociation of the aggregate. Therefore, the melting can be monitored as a function of temperature at either 260 or 520 nm. The melting curves at both wavelengths are observed to be similar, demonstrating that these melting processes are closely correlated [41].

Effects Of External Variables On The Phase Transition

Much like other colloidal suspensions [48–50], DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies have been shown to exhibit unique phase behavior. The aggregation and melting of these assemblies are sensitive to several experimental parameters, including nanoparticle size [41], DNA grafting density [51], DNA length, interparticle distance, and electrolyte concentrations.

Figure 4 (top) displays the melting curves for 10-, 20-, and 40-nm gold particle assemblies with linker DNA [41]. The melting transition width is about 5 K, compared to 12 K for melting of free DNA. The transition width, as well as the melting temperature, has been modified by the binding to gold particles. It is also evident that the melting properties depend on the gold nanoparticle size. For bigger gold particles, the melting temperature is higher. Figure 4 (bottom) shows the melting curves from theoretical calculations, which are consistent with the experimental observations and provides insight into the aggregation mechanism.

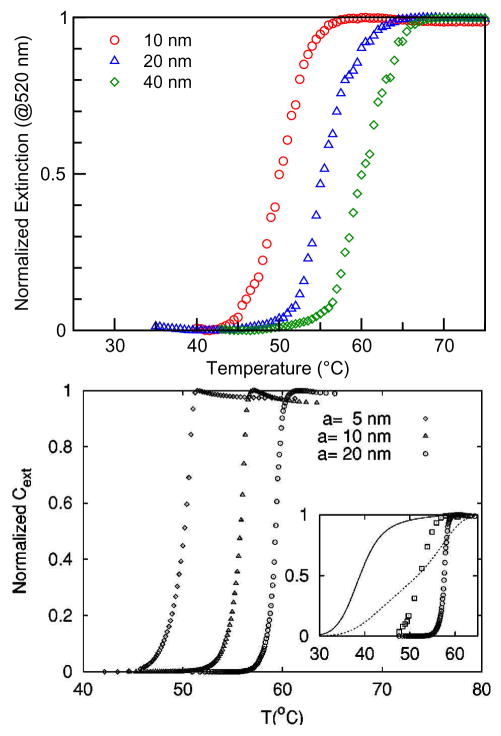

Fig. 4.

Top: Normalized experimental melting curves from extinction spectra taken at 520 nm for DNA-linked gold nanoparticle assemblies with various particle sizes. Reprint from Kiang [41]. Bottom: Melting curves from calculated extinction spectra at 520 nm as a function of particle size. The inset shows the melting curves for free DNA duplexes and particle-attached DNA with different aggregated structures. The shape and relative shifts of melting temperature calculated from a reaction-limited cluster-cluster aggregation cluster of 1000 particles resembles the experimental melting curves. Reprint from Park and Stroud [52].

A high DNA grafting density on the gold nanoparticle is expected to provide an advantage in increasing hybridization efficiency. Experimental results [51] show that, for temperature below 70 °C, the melting temperature is proportional to the DNA grafting density when the nanoparticle and target concentrations are kept constant. Also, a slight broadening of the melting transition was observed as DNA density decreases.

The interparticle distance is another parameter to control the melting properties. As gold nanoparticles are linked together via DNA hybridization, the amount of extinction due to scattering is influenced by the interparticle spacing. Interparticle distance also influences van der Waals and electrostatic forces between the particles, weakly affecting duplex DNA stability and hybridization properties. Experimental results show that the melting temperature increases with the length of the interparticle distance for temperatures below 70 °C, and there is a linear relationship between the two [51].

The melting behavior of DNA-linked nanoparticle assemblies also depends on the salt concentration. The melting temperature increases as salt concentration is increased from 0.05 to 1.0 M while keeping the nanoparticle and linker DNA concentration constant [51]. Moreover, increasing salt concentration also results in larger aggregates, as evidenced by a larger absorption change during melting. It is believed that the salt brings about a screening effect that minimizes electrostatic repulsion between the DNA-DNA bases and between the nanoparticles, hence, strengthening the effect of the linker bond.

Effects Of Disorder And Defects On The Phase Transition

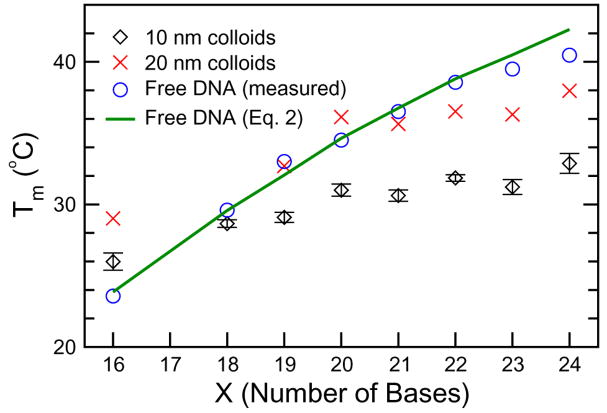

The melting temperature of the DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies depends not only on many external experimental parameters, but also on disorder and defects in the DNA base-pairing. Experimental results show an unusual trend in the melting temperature of DNA-nanoparticle assemblies brought about by the disorder introduced when using linkers that result in DNA duplexes of unequal length [53]. It was observed that, in DNA-nanoparticle assemblies with a fixed interparticle distance, the melting temperature does not increase monotonically with DNA linker length, unlike that of analogous free DNA duplexes, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Trends in melting temperature with respect to DNA linker length for DNA-linked nanoparticle assemblies. Experimental data for 10- and 20-nm gold nanoparticles, as well as free DNA in solution, are shown. The solid line represents melting temperatures for free DNA predicted from an empirical equation. Reprint from Harris and Kiang [53].

As the length (measured in number of bases) of linker DNA increases, the melting temperature of nanoparticle assemblies increases more when DNA linkers are composed of an even number of bases and increases less or decreases otherwise. For example, in a DNA-nanoparticle system with two noncomplimentary 12-base probes, a 22-base linker was observed to have a higher melting temperature than a 23-base linker. Note that a DNA linker with an even number of bases forms DNA duplexes of equal length, whereas a linker with an odd number of bases creates unequal duplex lengths. Continuing from the above example, a 22-base linker forms an 11-base duplex on each probe, while a 23-base linker forms an 11-base duplex on one probe and a 12-base duplex on the other. Despite the binding energy gain that results from increasing DNA linker length from 22 to 23 by a single base, DNA linkers with an odd number of bases result in DNA probe sets with unequal duplex lengths and, thus, different binding energies, thereby introducing disorder into the assembly and lowering the system’s overall stability.

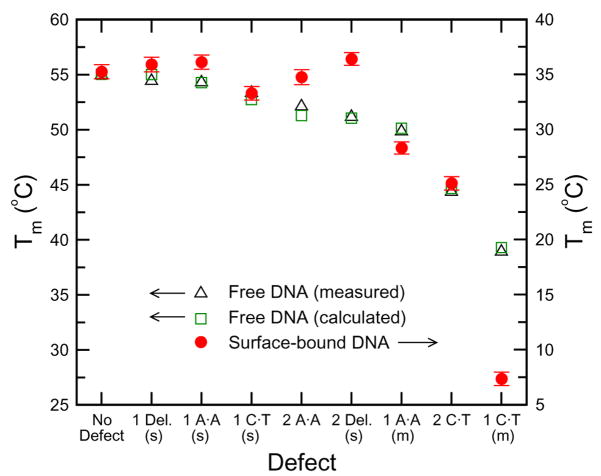

The melting temperature of DNA-linked nanoparticle aggregates also depends on the types and locations of base-pairing defects within the linker DNA sequence. While it has been suggested that the DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies can distinguish single base defects using change in melting temperature, it has also been shown that not all base-pairing defects result in a decrease in melting temperature for an aggregate [54]. In a study of different defects, to include base pair mismatches and deletions of different types, number, and location, the surface-bound DNA in nanoparticle assemblies was observed to have different hybridization behavior than free DNA, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Melting temperatures for nanoparticle assemblies with various linker DNA defects. The melting temperature for analogous sequences of free DNA is always lower with the presence of defects, whereas the melting temperature of surface-attached DNA sometimes increases when there is a defect in DNA base-pairing. Reprint from Harris and Kiang [54].

It is found that some single base mismatches and deletions near the surface of the probe particles increase melting temperature of the DNA-nanoparticle assembly. Specifically, one- and two-base deletions at the ends of certain linker DNA sequences are shown to increase the melting temperature of the DNA-nanoparticle system. It is concluded that deletions at the end of the linker, or at the particle surface, tend to increase melting temperature because they decrease electrostatic repulsion between the particle surface and the nearby paired base. Particular single base defects, such as a single AA base pair mismatch at the end of the linker sequence, increase the melting temperature of DNA-nanoparticle aggregates. This is because different DNA bases have different levels of affinity for gold particle surfaces. The cases where single base mismatches at the surface of a probe particle increase the melting temperature of the assembly can be attributed to nonspecific binding between the surface and the unpaired, dangling base. These results demonstrate that melting temperature of DNA-nanoparticle systems can be used to distinguish single base defects within linker DNA sequences; however, hybridization behaviors for surface-bound DNA differ from those of free DNA, and this should be considered when using this system for detection purposes.

Conclusions

Due to its unique recognition capabilities, physicochemical stability, mechanical rigidity, and high precision processibility, DNA is a promising material for biomolecular nanotechnology. The study of DNA-based nanostructures is, hence, an attractive topic. This review describes a model system of such DNA-based nanostructures, i.e., the DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies. The preparation and the optical properties investigated using optical absorption spectroscopy are described in detail. The melting transition of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies differs from that of free DNA. The phase transitions are influenced by many parameters, such as nanoparticle size, DNA sequence, density, length, interparticle distance, and electrolyte concentration. The change in optical property due to self-assembly of DNA-linked nanoparticles demonstrates that the system has potential to be used as a novel technology for DNA detection. In addition, the DNA-gold nanoparticle network is a system with experimentally tunable parameters that can be used to study the properties of complex fluids. The organization and structure of the system will allow us to explore compelling science that is not found in other less ordered systems like a gel. Understanding of the phase behavior of such a novel nanoparticle system may lead to the development of improved sensitivity and accuracy in DNA detection that can take advantage of the unique behavior of DNA-gold nanoparticle assemblies.

Acknowledgments

We also thank NSF DMR-0505814, NIH 1T90DK70121-01, Hamill Innovation Fund, and Welch Foundation C-1632 for support.

References

- 1.Frank-Kamenetskii MD. Biophysics of the DNA molecule. Phys Rep. 1997;288:13–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson JD, Crick FHC. Molecular structure of nucleic acids. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. doi: 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirkin CA, et al. A DNA-based method for rationally assembling nanoparticles into macroscopic materials. Nature. 1996;382:607–609. doi: 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alivisatos AP, et al. Organization of nanocrystal molecules using DNA. Nature. 1996;382:609–611. doi: 10.1038/382609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mucic RC, et al. DNA-directed synthesis of binary nanoparticle network materials. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12674–12675. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda Y, et al. Two-dimensional assembly of gold nanoparticles with a DNA network template. Appl Phys Lett. 2001;79:1181–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffer JL, et al. Dictation of the shape of mesoscale semiconductor nanoparticle assemblies by plasmid DNA. Appl Phys Lett. 1996;69:3851–3853. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torimoto T, et al. Fabrication of CdS nanoparticle chains along DNA double strands. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8799–8803. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell G, et al. Programmed assembly of DNA functionalized quantum dots. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8122–8123. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pathak S, et al. Hydroxylated quantum dots as luminescent probes for in situ hybridization. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4103–4104. doi: 10.1021/ja0058334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassell AM, et al. Assembly of DNA/fullerene hybrid materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1528–1531. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980619)37:11<1528::AID-ANIE1528>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun E, et al. DNA-templated assembly and electrode attachment of a conducting silver wire. Nature. 1998;391:775–778. doi: 10.1038/35826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin BR, et al. Orthogonal self-assembly on colloidal gold-platinum nanorods. Adv Mater. 1999;11:1021–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan H, et al. DNA-templated self-assembly of protein arrays and highly conductive nanowires. Science. 2003;301:1882–1884. doi: 10.1126/science.1089389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsang SC, et al. Immobilization of platinated and iodinated oligonucleotides on carbon nanotubes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1997;36:2197–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Z, et al. Immobilization and visualization of DNA and proteins on carbon nanotubes. Adv Mater. 1998;10:701–703. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen RJ, et al. Noncovalent sidewall functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes for protein immobilization. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3838–3839. doi: 10.1021/ja010172b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shim M, et al. Functionalization of carbon nanotubes for biocompatibility and biomolecular recognition. Nano Lett. 2002;2:285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker SE, et al. Covalently bonded adducts of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) oligonucleotides with single-wall carbon nanotubes: Synthesis and hybridization. Nano Lett. 2002;2:1413–1417. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwyer C, et al. DNA-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotechnology. 2002;13:601–604. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elghanian R, et al. Selective colorimetric detection of polynucleotides based on the distance-dependent optical properites of gold nanoparticles. Science. 1997;277:1078–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storhoff JJ, et al. One-pot colorimetric differentiation of polynucleotides with single base imperfections using gold nanoparticle probes. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:1959–1964. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan WCW, Nie S. Quantum dot bioconjugates for ultrasensitive nonisotopic detection. Science. 1998;281:2016–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He L, et al. Colloidal Au-enhanced surface plasmon resonance for ultrasensitive detection of DNA hybridization. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9071–9077. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SJ, et al. Array-based electrical detection of DNA with nanoparticle probes. Science. 2002;295:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1067003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, et al. Magnetically-induced solid-state electrochemical detection of DNA hybridization. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4208–4209. doi: 10.1021/ja0255709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao YC, et al. Nanoparticles with raman spectroscopic fingerprints for DNA and RNA detection. Science. 2002;297:1536–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5586.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxwell DJ, et al. Self-assembled nanoparticle probes for recognition and detection of biomolecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9606–9612. doi: 10.1021/ja025814p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weizmann Y, et al. Amplified DNA sensing and immunosensing by the rotation of functional magnetic particles. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3452–3454. doi: 10.1021/ja028850x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerion D, et al. Sorting fluorescent nanocrystals with DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7070–7074. doi: 10.1021/ja017822w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Y, Kiang CH. Nanobiotechnology. Vol. 2. American Scientific Publishers; Stevenson Ranch, CA, USA: 2005. Handbook of Nanostructured Biomaterials and Their Applications; pp. 224–246. chap. VII. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson VJ, Lekkerkerker HNW. Insights into phase transition kinetics from colloid science. Nature. 2002;416:811–815. doi: 10.1038/416811a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kushon SA, et al. Detection of single nucleotide mismatches via fluorescent polymer superquenching. Langmuir. 2003;19:6456–6464. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lockhart DJ, Winzeler EA. Genomics, gene expression and DNA arrays. Nature. 2000;405:827–836. doi: 10.1038/35015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill AA, et al. Genomic anlaysis of gene expression in C. elegans. Science. 2000;290:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou B, et al. Human antibodies against spores of the genus Bacillus: A model study for detection of and protection against anthrax and the bioterrorist threat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5241–5246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082121599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Lu Y. Adenosine-dependent assembly of aptazyme-functionalized gold nanoparticles and its application as a coloimetric biosensor. Anal Chem. 2004;76:1627–1632. doi: 10.1021/ac0351769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipshutz RJ, et al. High density synthetic oligonucleotide arrays. Nature Genet. 1999;21:20–24. doi: 10.1038/4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Austin RH, et al. Stretch genes. Phys Today. 1997;50:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taton TA, et al. Scanometric DNA array detection with nanoparticle probes. Science. 2000;289:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiang CH. Phase transition of DNA-linked gold nanoparticles. Physica A. 2003;321:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, et al. The reversible phase transition of DNA-linked colloidal gold assemblies. Physica A. 2005;354:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukatsky DB, Frenkel D. Phase behavior and selectivity of DNA-linked nanoparticle assemblies. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92:068302-1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.068302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drukker K, et al. Model simulations of DNA denaturation dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:579–590. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Y, et al. Melting transition of directly-linked gold nanoparticle DNA assembly. Physica A. 2005;350:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lazarides AA, Schatz GC. DNA-linked metal nanosphere materials: Structural basis for the optical properties. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Spectral properties and relaxation dynamics of surface plasmon electronic oscillations in gold and silver nanodots and nanorods. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8410–8426. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen I, et al. Shear-induced configurations of confined colloidal suspensions. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:046001-1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.046001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schall P, et al. Visualization of dislocation dynamics in colloidal crystals. Science. 2004;305:1944–1948. doi: 10.1126/science.1102186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manley S, et al. Limits to gelation in colloidal aggregation. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:108302-1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.108302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin R, et al. What controls the melting properties of DNA-linked gold nanoparticle assemblies? J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1643–1654. doi: 10.1021/ja021096v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park SY, Stroud D. Theory of melting and the optical properties of gold/DNA nanocomposites. Phys Rev B. 2003;67:212202-1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris NC, Kiang CH. Disorder in DNA-linked gold nanoparticle assemblies. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95:046101-1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.046101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris NC, Kiang CH. Defects can increase the melting temperature of DNA-nanoparticle assemblies. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:16393–16396. doi: 10.1021/jp062287d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]