Abstract

Objective To describe the long term costs, health benefits, and cost effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery compared with those of continued medical management for patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Design We estimated resource use and costs for the first year on the basis of data from the REFLUX trial. A Markov model was used to extrapolate cost and health benefit over a lifetime using data collected in the REFLUX trial and other sources.

Participants The model compared laparoscopic surgery and continued proton pump inhibitors in male patients aged 45 and stable on GORD medication.

Intervention Laparoscopic surgery versus continued medical management.

Main outcome measures We estimated quality adjusted life years and GORD related costs to the health service over a lifetime. Sensitivity analyses considered other plausible scenarios, in particular size and duration of treatment effect and the GORD symptoms of patients in whom surgery is unsuccessful.

Main results The base case model indicated that surgery is likely to be considered cost effective on average with an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £2648 (€3110; US$4385) per quality adjusted life year and that the probability that surgery is cost effective is 0.94 at a threshold incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £20 000. The results were sensitive to some assumptions within the extrapolation modelling.

Conclusion Surgery seems to be more cost effective on average than medical management in many of the scenarios examined in this study. Surgery might not be cost effective if the treatment effect does not persist over the long term, if patients who return to medical management have poor health related quality of life, or if proton pump inhibitors were cheaper. Further follow-up of patients from the REFLUX trial may be valuable.

Trial registration ISRCTN15517081.

Introduction

Around 25% of adults in Western society experience intermittent heartburn, one of the cardinal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).1 2 Once diagnosed with erosive (persistent) GORD, patients often require lifelong pharmacotherapy, usually proton pump inhibitors.3 Although considered effective, there are concerns about the long term side effects of proton pump inhibitors, and expenditure on these drugs remains considerable, despite recent reductions in prices. In general practice in England expenditure was £233m (€274m; US$386m) in 2007.4 Laparoscopic fundoplication is now an alternative way to treat GORD. In addition to potential clinical benefits laparoscopic surgery should lead to the avoidance of continual medication and its associated costs. Several studies have examined economic characteristics of laparoscopic surgery.5 6 7 8 Of those that compared surgery with GORD medication, Bojke8 found that surgery was cost effective, and Cookson6 concluded that laparoscopic surgery had similar costs to medical management after eight years and was cost saving thereafter. Arguedas evaluated the strategies in a United States setting and concluded that medical therapy dominated surgery using a 10 year time horizon, assuming a higher rate of symptom recurrence and re-operation after surgery than in the surgery groups in the UK based studies.5 None of these studies, however, used estimates of health related quality of life derived from a randomised clinical trial comparing laparoscopic fundoplication with medical management, which is of central importance to the evaluation of these treatments. This paper updates the economic study by Bojke8 to incorporate one year health related quality of life data from the REFLUX trial.9

The multicentre REFLUX trial compared a strategy of laparoscopic surgery with one of continued medical management for patients with reasonable symptom control on GORD medications.9 The clinical and patient assessed outcomes of the trial up to one year after surgery have recently been reported. Although these findings showed clear benefits of surgery at this time in terms of health related quality of life, decision makers are also interested in the costs and cost effectiveness of the two forms of management. GORD is usually a chronic condition and a key issue is the extent to which benefits are sustained. Surgery is costly in the short term, but these costs may be at least partly offset by reductions in lifetime use of GORD medication. Extrapolation of health benefits and costs are thus needed to provide a meaningful estimate of cost effectiveness.

Methods

Overview

We used a model comparing laparoscopic surgery and continued use of proton pump inhibitors in male patients aged 45 (the median age and predominant sex in the REFLUX trial9), and stable on anti-GORD medication. Over a lifetime horizon, health benefits were quantified in terms of quality adjusted life years and costs were assessed from the perspective of the United Kingdom’s NHS in 2008/2009 prices. Future costs and health benefits are discounted (adjusted to current values) at 3.5% per year, in accord with UK guidelines for economic evaluation.10

Model structure

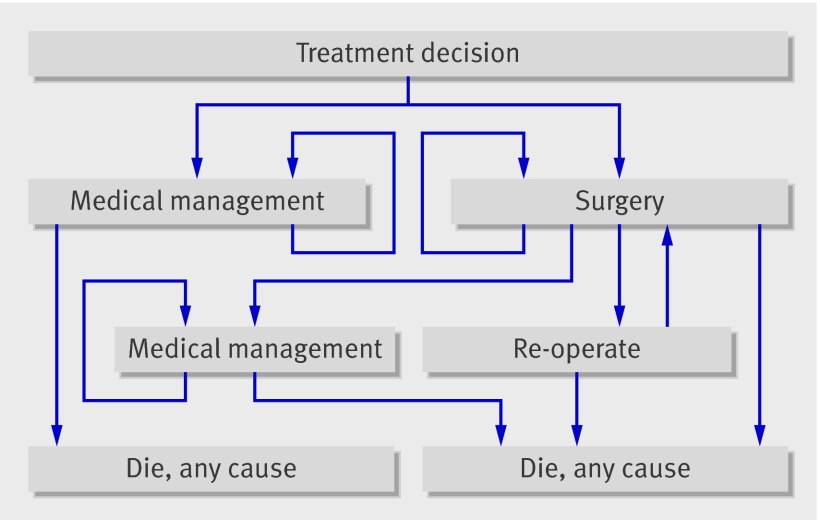

Figure 1 shows the model structure. It is a discrete time Markov cohort model with a cycle length of one year. Patients follow a strategy of either early laparoscopic surgery or continuation of medical management (without the option of surgery after failure of medical management).

Fig 1 Model structure

In the model, surgery may “fail” in one of two ways. Patients may need revision of surgery, either to improve symptom control or because of surgical complications, or they may return to use of long term medical management because of continued symptoms.11

This model assumes that patients in the medical management arm are stable on GORD medication. This assumption follows the inclusion criteria for the REFLUX trial. As a result “treatment failure” is not defined as a health state in the model. Annual costs of medical management are estimated using mean consumption of proton pump inhibitors during the REFLUX trial, incorporating any changes to dose or medication, and it is assumed that the estimate of health related quality of life includes, on average, remission or any side effects of medication. The base case assumes that, if surgical patients do not need to return to medical management or need revision of surgery, the relative difference in health related quality of life of surgery over medical management will be maintained over their lifetime. We used sensitivity analyses to consider other scenarios where the treatment effect (the difference in health related quality of life between medical management and those who do not fail surgery) only lasts for one, two, or five years. In these alternative scenarios, health related quality of life is the same in the surgery group as in the medical management group after the “treatment effect” ends, even in patients who do not return to the use of proton pump inhibitors.

Evidence used in the model

Costs for the first year in the model were estimated from the REFLUX trial.9 The trial collected data on use of health service resources up to one year, including inpatient days in hospital wards and high dependency units, diagnostic tests, duration in theatre, outpatient and general practitioner visits, re-admissions, and use of GORD medication. These resources were costed using routine NHS unit costs and prices (table 1).

Table 1.

Health related quality of life (HRQOL) estimates and rates of events used in model

| Parameter | Mean (SE)* | Distribution for PSA | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRQOL | |||

| HRQOL while on medical management, or return to medical management | 0.711 (0.018) | Gamma† | Baseline EQ5D of patients randomised in REFLUX trial12 |

| Additional HRQOL after successful laparoscopic surgery compared with medical management | |||

| Adjusted treatment received‡ | 0.068 (0.038) | Normal | REFLUX12 |

| Intention to treat§ | 0.047 (0.026) | Normal | REFLUX12 |

| Per protocol¶ | 0.076 (0.028) | Normal | REFLUX12 |

| HRQOL for general male population | |||

| Aged 45-55 | 0.84 | Kind 199919 | |

| Aged 55-65 | 0.78 | Kind 199919 | |

| Aged 65-75 | 0.78 | Kind 199919 | |

| Aged 75+ | 0.75 | Kind 199919 | |

| Rates of events | |||

| Return to medical management after surgery | 460 events, 9389 patient years | Gamma | Meta-analysis12 |

| Revision of surgery | 53 events, 6720 patient years | Gamma | Meta-analysis12 |

| Operative mortality | 4 deaths, 3397 patients | Beta | Meta-analysis8 |

SE=standard error, PSA=probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

*Unless otherwise indicated.

‡Adjusted treatment received is estimated by linear model using treatment received indicator variable as a covariable. The residual of regression of treatment received on the randomisation indicator variable is included as another covariable to adjust for confounders.17 This is the base case used in the model.

§Intention to treat is the mean difference between randomised groups adjusting for body mass index, age, sex, and baseline score.

¶Per protocol is the difference between the randomised groups using only participants who received their allocated GORD management adjusting for BMI, age, sex, and baseline score.

†The decrement in HRQOL (utility) on medical management compared with the general age-matched population is parameterised in the stochastic model by a gamma distribution with a mean of 1-0.711 and a standard error of 0.018.

We calculated rates of return to medical management and revision of surgery using data from the REFLUX trial and studies identified through a literature search.8 12 The average rate of return to medical management overall was 4.9 per 100 person years and the average rate of revision of surgery was 0.8 per 100 person years, although rates seemed to vary considerably between studies. As we did not find evidence that this variation was related to length of follow-up, we assumed that the annual rate of surgical failure was constant over time. Details of the literature searches and meta-analyses are available in the Health Technology Assessment monograph.12 Sensitivity analyses were undertaken assuming higher and lower rates of failure.

After the first year, all patients require an annual visit to their general practitioner. It was assumed that patients who fail surgery need an additional visit to their general practitioner and to a hospital specialist. No hospital admissions or outpatient visits for GORD related reasons were included after one year for patients with successful surgery.13

Patients can die of other causes,14 and the model assumed the same age and sex specific risk of mortality as the UK general population. Although no deaths from surgery or revision occurred in the REFLUX trial, a small additional risk of operative mortality was assumed, estimated by a meta-analysis (four deaths in 4000 procedures).8

Estimating quality adjusted life years

The REFLUX trial measured health status using the generic EuroQol EQ-5D instrument.15 Each of the possible 243 health states was mapped to a preference based value (or “utility”) where zero represents a state equivalent to death and one represents full health.16 Table 1 shows the mean differences in utility between treatments at one year estimated by the REFLUX trial.12 No other randomised trials have compared surgery with medication using a preference based measure of health related quality of life.

We assumed that the “adjusted treatment received” analysis of the REFLUX trial12 was the most appropriate measure of the effect of surgery on health related quality of life to use in the base case model. This approach identifies the efficacy of surgery in patients who are most likely to comply with their clinicians’ recommendations for treatment.17 18 We also used intention to treat and per protocol estimates in sensitivity analyses.

In the model, we use the term “treatment effect” to refer to the difference in health related quality of life between medical management and those who do not fail surgery. This value differs from the estimates calculated in the trial, which measured the mean difference in health related quality of life between medical management and surgery, whether failed or not. As those who fail surgery would be expected to have lower health related quality of life than those who do not, this approach estimates a lower bound for the benefits of surgery by the model.

We estimated the health related quality of life of the 15 patients in the surgery group of the REFLUX trial who required proton pump inhibitors at one year to be 0.68 (standard error 0.048) using the EQ5D, a decrease of 0.04 from baseline. In view of the small sample of patients and short follow-up, it was assumed in the base case analysis that patients who needed proton pump inhibitors after surgery returned to their baseline (pre-surgery) health related quality of life, consistent with clinical opinion (Robert Heading, personal communication, 2008) that proton pump inhibitors are just as effective after surgery as before, provided they are being used to treat reflux symptoms. This assumption was varied in sensitivity analysis.

To account for the decline in health related quality of life with age, the mean utility for medical management observed at the end of the REFLUX trial was compared with the average utility for the general population aged 45-5519 to calculate a proportionate decrement in utility for that health state. It was assumed that this proportionate decrement was constant as the cohort aged (table 1).

Analysis

We did calculations using Excel. The model estimated mean costs and quality adjusted life years in each treatment cohort. Where one treatment did not dominate the other, the incremental cost effectiveness ratio was calculated as the ratio of the difference in expected costs to the difference in expected quality adjusted life years. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was done by assigning probability distributions to the model inputs, rather than treating them as point estimates.20 This analysis calculated the overall uncertainty in the treatment decision as the proportion of simulations where laparoscopic surgery is cost effective, given threshold values for the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £20 000 and £30 000 per quality adjusted life year as used by the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence.10

Results

Table 2 shows the use of health service resources and cost for GORD related causes during the first year of follow-up in the REFLUX trial,12 for patients receiving their randomised treatment per protocol. Total costs were £370 per patient in the medical management arm and £2709 in the surgical arm, a difference of £2339 (95% confidence interval 2147 to 2558; calculated with bias corrected accelerated bootstrap).21

Table 2.

Mean use of healthcare resources and costs for GORD related causes in REFLUX trial12 for patients receiving their randomised treatment per protocol and followed up for one year

| Unit cost (£) |

Source* | Unit of measure | Medical (n=155) | Surgery (n=104) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any use (%) | Mean use | Mean cost (£) | SD (£) | Any use (%) | Mean use | Mean cost (£) | SD (£) | |||||

| Endoscopy | 172 | a | Tests | — | — | — | — | 88 | 0.88 | 151 | 57 | |

| pH tests | 64 | a | Tests | — | — | — | — | 70 | 0.70 | 45 | 29 | |

| Manometry | 61 | a | Tests | — | — | — | — | 66 | 0.66 | 40 | 29 | |

| Operation time | 4 | a | Minutes | — | — | — | — | 100 | 114.5 | 420 | 137 | |

| Consumables | 825 | a | — | — | — | — | — | 100 | 1.00 | 825 | 0 | |

| Ward | 264 | b | Days | — | — | — | — | 100 | 2.34 | 619 | 354 | |

| High dependency | 657 | b | Days | — | — | — | — | 1 | 0.05 | 32 | 322 | |

| Total surgery | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2132 | 475 | |

| Visit to GP | 36 | c | Visits | 44 | 1.16 | 42 | 71 | 44 | 1.14 | 42 | 60 | |

| Visit from GP | 58 | c | Visits | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 0.02 | 1 | 8 | |

| Outpatient | 88 | b | Visits | 14 | 0.30 | 27 | 76 | 43 | 0.54 | 47 | 64 | |

| Day case | 896 | b | Admit | 10 | 0.14 | 127 | 426 | 42 | 0.47 | 422 | 572 | |

| Inpatient | 1259 | b | Admit | 3 | 0.03 | 32 | 200 | 4 | 0.04 | 48 | 243 | |

| Subsequent costs | — | — | — | — | — | 229 | 632 | — | — | 560 | 728 | |

| Medication costs | — | d | — | — | — | 141 | 144 | — | — | 16 | 52 | |

| Total costs | — | — | — | — | — | 370 | 638 | — | — | 2709 | 941 | |

*Sources of unit costs used in the analysis: (a) Mean unit costs of a survey of five participating centres, 2003, updated for inflation,8 (b) mean hospital costs for England and Wales, 2006/07,25 (c) Curtis et al, 2008,26 (d) British National Formulary, 200924 and REFLUX.12

Under base case assumptions, the model predicts that, for example, by five years 17.7% of surgery patients will have returned to medical management, 2.9% will have undergone a re-operation, and 0.1% will have died during surgery. The average discounted lifetime cost per patient of surgery was £5026, made up of the initial cost of the cost of surgery (£2132), repair of surgery (£746), return to medical management (£1360) and other health care (£788). The discounted lifetime cost of the medical management group was £3411. Therefore, surgery had an additional mean cost of £1616. The mean difference in quality adjusted life years was 0.61, equating to an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £2648 per quality adjusted life year (table 3, scenario 1). In the base case, the probability that surgery is cost effective at a cost effectiveness threshold of £20 000 is 0.94.

Table 3.

Results of base case economic model and sensitivity analyses. Expected costs and QALYs per patient in each scenario were calculated as mean of 1000 simulations using probabilistic model

| Scenario | Key input values | Model results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of effect | Utility difference for successful surgery | Utility after failure of surgery | QALY differ-ence | Cost differ-ence (£) | ICER (£/QALY) | P (20k) | P (30k) | |

| (1) Base case | 20 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.61 | 1616 | 2648 | 0.944 | 0.953 |

| Univariate (one way) sensitivity analyses | ||||||||

| (2) ITT estimate of treatment effect | 20 | 0.047 | 0.711 | 0.42 | 1616 | 3876 | 0.918 | 0.935 |

| (3) Per-protocol estimate of treatment effect | 20 | 0.076 | 0.711 | 0.68 | 1616 | 2363 | 0.989 | 0.992 |

| (4) Treatment effect lasts 1 year | 1 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.05 | 1616 | 32 534 | 0.204 | 0.429 |

| (5) Treatment effect lasts 2 years | 2 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.11 | 1616 | 14 807 | 0.659 | 0.788 |

| (6) Treatment effect lasts 5 years | 5 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.26 | 1616 | 6232 | 0.88 | 0.899 |

| (7) Worse HRQOL after failure of surgery than MM group | 20 | 0.068 | 0.680 | 0.37 | 1616 | 4405 | 0.768 | 0.792 |

| (8) Higher annual probability of return to MM (11.2%) than base case (4.9%) | 20 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.42 | 1978 | 4744 | 0.899 | 0.928 |

| (9) Higher annual probability of repair of surgery (4%) than base case (0.8%) | 20 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.63 | 3890 | 6189 | 0.87 | 0.905 |

| (10) Higher probability of operative mortality of surgery or repair (1%) than base case (0.1%) | 20 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.46 | 1579 | 3425 | 0.878 | 0.888 |

| (11) 100% increase in cost of surgery | 20 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.61 | 3927 | 6437 | 0.877 | 0.909 |

| (12) 50% reduction in annual expenditure on PPIs compared with base case | 20 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.61 | 2392 | 3921 | 0.91 | 0.931 |

| Multivariate (two-way and three-way) sensitivity analyses | ||||||||

| (13) Duration of treatment effect is for five years and worse HRQOL if fail surgery | 5 | 0.068 | 0.680 | 0.02 | 1616 | 101 290 | 0.383 | 0.428 |

| (14) ITT estimate and duration of treatment effect is for five years | 5 | 0.047 | 0.711 | 0.17 | 1616 | 9269 | 0.807 | 0.859 |

| (15) ITT estimate and duration of treatment effect is for five years and worse HRQOL if fail surgery | 5 | 0.047 | 0.680 | −0.07 | 1616 | Dom | 0.213 | 0.248 |

| (16) 50% reduction in annual expenditure on PPIs and duration of treatment effect is two years | 2 | 0.068 | 0.711 | 0.11 | 2392 | 21 923 | 0.455 | 0.683 |

Dom=surgery is dominated with higher costs and lower QALYs than MM (and no ICER is calculated); HRQOL=health related quality of life, ICER=incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ITT=intention to treat analysis; MM=medical management; PPI=proton pump inhibitors; P(20k)=probability surgery is cost effective at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000; P(30k)= probability surgery is cost effective at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £30 000.

We explored several scenarios regarding the size and duration of treatment effect, GORD symptoms of those who fail surgery and costs (table 3). Use of intention –to treat and per protocol estimates of effect did not change the conclusion that surgery is cost effective assuming a threshold of £20 000 per quality adjusted life year gained. The probability that surgery is cost effective decreases to 0.77 if patients who return to proton pump inhibitors have worse GORD symptoms than before surgery (scenario 7). Surgery is unlikely to be cost effective if it is assumed that its benefits (in terms of health related quality of life relative to medical management) are not maintained beyond one year (scenario 4).

Surgery might also not be cost effective in some multivariate sensitivity analyses. For example, the incremental cost effectiveness ratio increases to about £22 000 if proton pump inhibitors can be effectively delivered at half the cost estimated here—perhaps due to greater use of lower cost drugs—and there is no difference in health related quality of life after two years (scenario 16).

Discussion

Principal findings

Under base case assumptions, surgery is cost effective on average with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £2648 per quality adjusted life year. The probability of surgery being cost effective is high given a threshold of £20 000 per quality adjusted life year and assuming the treatment effect lasts for at least five years and patients who fail surgery do not have worse symptoms than before surgery.

The results of this analysis are similar to those of Bojke8 who also found surgery to be cost effective. That model was constructed using baseline utility data from the REFLUX trial but did not include the treatment effect of surgery at one year.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

We have compared the cost effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery with that of medical management using randomised data on the effect of treatment on health related quality of life.

The REFLUX trial was a pragmatic study and the results, in terms of symptom control and health related quality of life, are expected to be generalisable to patients in the UK who are stable on GORD medication and suitable for surgery.22 Nevertheless, because rates of surgical reintervention and return to medical management in clinical practice might differ from the trial or with longer follow-up,23 we have used mean rates from a literature review to inform this analysis.

In the base case we used the “adjusted treatment” received estimate of the treatment efficacy. Intention to treat and per protocol estimates were also used in sensitivity analyses. The intention to treat analysis is an unbiased estimate of effectiveness but is diluted by the high proportion (38%) of patients in the REFLUX trial who were randomised to surgery but did not receive it.12 The most common reason given for non-compliance was patient choice, which was thought to be affected by long waiting times.12 Given that waiting times vary between centres and over time, the intention to treat estimate in the REFLUX trial might not be generalisable to current practice in the NHS. The per protocol analysis adjusting for baseline age, sex, body mass index, and EQ-5D score is another measure of the efficacy of surgery12 but using regression to adjust for observed baseline characteristics may not adequately control for selection bias. Regardless of whether an adjusted treatment received, intention to treat or per protocol analysis is conducted, surgery appears to be cost effective at the thresholds used by NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence), if it is assumed that health related quality of life is maintained over the long term.

Costs of medication were calculated using current pack prices24 applied to the prescribing pattern observed in REFLUX.12 Some evidence indicates that prescribers have been switching to lower cost proton pump inhibitors such as lansoprazole or omeprazole following sharp reductions in their prices in recent years, and consequently the current cost of medical management may be lower than estimated here.4 However, surgery remains cost effective even if the annual cost of medication is half that in the base case, other considerations being equal. Nevertheless, in some scenarios surgery is unlikely to be cost effective, particularly where costs of medical management are lower than calculated in the base case and the health related quality of life benefit of surgery is not maintained over the long term.

The duration of the treatment effect is, therefore, an important but uncertain assumption. To inform this question, follow up of REFLUX trial patients has been extended to five years. Given the results of the trial so far and the assumptions made in the decision model, extending the follow up of the trial from one year (scenario 4) to five years (scenario 6) would increase the probability that surgery is cost effective at a threshold of £20 000 per quality adjusted life year from 0.20 to 0.88. However, under more pessimistic assumptions about health related quality of life of patients who return to medical management, then even five years of follow-up would still leave considerable uncertainty about the value of surgery.

Conclusions

Although surgery seems likely to be cost effective in terms of expected (mean) costs and health effects, uncertainty remains about the duration of the treatment effect and the severity of GORD symptoms after failure of surgery. Furthermore, a number of practical issues need to be considered before the NHS could offer surgery to all patients who are currently stable on medical management. In particular, surgical capacity and availability of trained surgeons are potential barriers to implementation that would need to be addressed.

What is already known on this topic

Laparoscopic surgery is an efficacious treatment of stable GORD that would otherwise require medical management

Surgery is costly in the short term, but these costs may be at least partly offset by less lifetime use of anti-GORD medication

What this study adds

This study compared the cost effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery and medical management using randomised data on the effect of treatment on health related quality of life

The findings indicate that laparoscopic surgery is cost effective provided that clinical benefits are sustained in the medium to long term

Trial team: Aberdeen—Marion Campbell, Adrian Grant, Craig Ramsay, Samantha Wileman; York—Garry Barton (1999-2002), Laura Bojke, David Epstein, Sue Macran, Mark Sculpher. Trial steering group: Wendy Atkin (independent chair), John Bancewicz, Ara Darzi, Robert Heading, Janusz Jankowski, Zygmunt Krukowski, Richard Lilford, Iain Martin (1997-2000), Ashley Mowat, Ian Russell, Mark Thursz. Data monitoring committee: Jon Nicholl, Chris Hawkey, Iain MacIntyre. Wendy Atkin, Janusz Jankowski, Richard Lilford, Jon Nicholl, Chris Hawkey, and Iain MacIntyre were independent of the trial. Members of the reflux trial group responsible for recruitment in the clinical centres were as follows. Aberdeen Royal Infirmary: A Mowat, Z Krukowski, E El-Omar, P Phull, T Sinclair, L Swan. Belfast Victoria Hospital: B Clements, J Collins, A Kennedy, H Lawther, B Mulvenna. Royal Bournemouth Hospital: D Bennett, N Davies, M McCullen, S Toop, P Winwood. Bristol Royal Infirmary: D Alderson, P Barham, K Green, R Mountford, S Tranter, R Mittal. Princess Royal University Hospital, Bromley: M Asante, L Barr, S El Hasani. Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh: A De Beaux, R Heading, L Meekison, S Paterson-Brown, H Barkell. Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford: G Ferns, M Bailey, N Karanjia, TA Rockall, L Skelly, M Smith. Hull Royal Infirmary: M Dakkak, J King, C Royston, P Sedman. Raigmore Hospital, Inverness: K Gordon, I McGauran, LF Potts, C Smith, PL Zentler-Munro, A Munro. General Infirmary at Leeds: A Axon, B Chanley, S Dexter, M McMahon, P Maoyeddi. Leicester Royal Infirmary: DM Lloyd, A Palmer-Jeffrey, B Rathbone. St Mary’s Hospital, London: V Loh, M Thursz, A Darzi. Whipps Cross Hospital, London: A Ahmed, R Greaves, A Sawyerr, J Wellwood, T Taylor. Poole Hospital: S Hosking, T Karlowski, S Lowrey, N Sharer, J Snook. Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth: H D Duncan, P Goggin, T Johns, A Quine, S Somers, S Toh. Hope Hospital, Salford: SEA Attwood, C Babbs, J Bancewicz, M Greenhalgh, W Rees, A Robinson. North Staffordshire Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent: T Bowling, Dr Brind, CVN Cheruvu, M Deakin, S Evans, R Glass, J Green, F Leslie, JB Elder. Morriston Hospital, Swansea: JN Baxter, P Duane, MM Rahman, M Thomas, J Williams. Princess Royal Hospital, Telford: J Bateman, D Maxton, N Moreton, A Sigurdsson, MSH Smith, G Townson. Yeovil District Hospital: N Beacham, C Buckley, S Gore, RH Kennedy, ZH Khan, J Knight, L Martin. York District Hospital: D Alexander, S Kelly, G Miller, D Parker, A Turnbull, J Turvill, W Wong, L Delaney.

Contributors: All authors took part in the REFLUX trial and have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript. MS was responsible for the economic evaluation section of the grant application and protocol, and LB and DE conducted the economic analysis for the paper.

Funding: This study was commissioned and funded by the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA). The funder of this study, other than the initial peer review process prior to funding and six-monthly progress reviews, did not have any involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NCCHTA or the funders that provide institutional support for the authors of this report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Approval for this study was obtained from the Scottish Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and the appropriate local research ethics committees.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2576

References

- 1.Kennedy T, Jones R. The prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in a UK population and the consultation behaviour of patients with these symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:1589-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Pinxteren B, Numans MME, Bonis P, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews 2006;3:CD002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDougall NI, Johnston BT, Kee F, Collins J, McFarland R, Love AH. Natural history of reflux oesophagitis: a 10 year follow up of its effect on patient symptomatology and quality of life. Gut 1996;38:481-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris L. Update on growth in prescription volume and cost in the year to December 2007. London: NHS Business Services Authority, 2008:1-13. www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk.

- 5.Arguedas MR, Heudebert GR, Klapow JC, Centor RM, Eloubeidi MA, Wilcox CM, et al. Re-examination of the cost-effectiveness of surgical versus medical therapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: the value of long-term data collection. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cookson R, Flood C, Koo B, Mahon D., Rhodes M. Short term cost effectiveness and long term cost analysis comparing laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with proton-pump inhibitor maintenance for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. B J Surg 2005;92:700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romagnuolo J, Meier MA, Sadowski DC. Medical or surgical therapy for erosive reflux esophagitis: cost-utility analysis using a Markov model. Ann Surg 2002;236:191-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bojke L, Hornby E, Sculpher M. A comparison of the cost effectiveness of pharmacotherapy or surgery (laparoscopic fundoplication) in the treatment of GORD. Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:829-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant A, Wileman S, Ramsay C, Mowat A, Krukowski Z, Heading R, et al. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: UK collaborative randomised trial. BMJ 2008;337:a2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: NICE, 2008. [PubMed]

- 11.Lundell L, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, et al. Comparing laparoscopic antireflux surgery with esomeprazole in the management of patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a 3-year interim analysis of the LOTUS trial. Gut 2008;57:1207-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant A, Wileman S, Ramsay C, Bojke L, Epstein D, Sculpher M, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of minimal access surgery amongst people with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—a UK collaborative study. The REFLUX Trial. Health Technol Assess 2008;12:1-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myrvold HE, Lundell L, Miettinen P, Pedersen S, Liedman B, Hatlebakk J, et al. The cost of long term therapy for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a randomised trial comparing omeprazole and open antireflux surgery. Gut 2001;49:488-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Statistics. KS02 age structure: census 2001, key statistics for local authorities. London: Office for National Statistics, 2005.

- 15.Kind P. The EuroQoL instrument: an index of health related quality of life. In: Spiker B, ed. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.

- 16.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. A social tariff for EuroQol: results from a UK general population survey (discussion paper 138). York: University of York: Centre for Health Economics, 1995.

- 17.Nagelkerke N, Fidler V, Bernsen R, Borgdor M. Estimating treatment effects in randomized clinical trials in the presence of non-compliance. Stat Med 2000;19:1849-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imbens G, Angrist J. Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica 1994;62:467-75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK population norms for EQ5D: Discussion paper 172. York (UK): Centre for Health Economics, 1999.

- 20.Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- 21.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1993.

- 22.Blazeby JM, Barham CP, Donovan JL. Commentary: Randomised trials of surgical and non-surgical treatment: a role model for the future. BMJ 2008;337:a2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieske B, Gordon A. Rapid responses: Evaluation of long term outcomes after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/337/dec15_2/a2664. BMJ 2008;337:a2664.19074946 [Google Scholar]

- 24.British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary 57. London, UK: British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009.

- 25.Department of Health. National schedule of reference costs 2006-07 for NHS trusts. London: Department of Health, 2008.

- 26.Curtis L, Netten A. Unit costs of health and social care 2008. Canterbury: University of Kent, 2008.