Abstract

Objective To estimate the extent of overdiagnosis (the detection of cancers that will not cause death or symptoms) in publicly organised screening programmes.

Design Systematic review of published trends in incidence of breast cancer before and after the introduction of mammography screening.

Data sources PubMed (April 2007), reference lists, and authors.

Review methods One author extracted data on incidence of breast cancer (including carcinoma in situ), population size, screening uptake, time periods, and age groups, which were checked independently by the other author. Linear regression was used to estimate trends in incidence before and after the introduction of screening and in older, previously screened women. Meta-analysis was used to estimate the extent of overdiagnosis.

Results Incidence data covering at least seven years before screening and seven years after screening had been fully implemented, and including both screened and non-screened age groups, were available from the United Kingdom; Manitoba, Canada; New South Wales, Australia; Sweden; and parts of Norway. The implementation phase with its prevalence peak was excluded and adjustment made for changing background incidence and compensatory drops in incidence among older, previously screened women. Overdiagnosis was estimated at 52% (95% confidence interval 46% to 58%). Data from three countries showed a drop in incidence as the women exceeded the age limit for screening, but the reduction was small and the estimate of overdiagnosis was compensated for in this review.

Conclusions The increase in incidence of breast cancer was closely related to the introduction of screening and little of this increase was compensated for by a drop in incidence of breast cancer in previously screened women. One in three breast cancers detected in a population offered organised screening is overdiagnosed.

Introduction

Screening for cancer may lead to earlier detection of lethal cancers but also detects harmless ones that will not cause death or symptoms. The detection of such cancers, which would not have been identified clinically in someone’s remaining lifetime, is called overdiagnosis and can only be harmful to those who experience it.1 As it is not possible to distinguish between lethal and harmless cancers, all detected cancers are treated. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are therefore inevitable.2

It is well known that many cases of carcinoma in situ in the breast do not develop into potentially lethal invasive disease.1 In contrast, many find it difficult to accept that screening for breast cancer also leads to overdiagnosis of invasive cancer. Harmless invasive cancer is common, however, even for lung cancer, with 30% overdiagnosis after long term follow-up of patients screened by radiography.2 Autopsy studies have shown that invasive prostate cancer occurs in about 60% of men in their 60s, whereas the lifetime risk of dying from such cancer is only about 3%.2 Autopsy studies have also found inconsequential breast cancer lesions. Thirty seven per cent of women aged 40-54 who died from causes other than breast cancer had lesions of invasive or non-invasive cancer at autopsy, and half were visible on radiography.3 4

Overdiagnosis can be measured precisely in a randomised trial with lifelong follow-up if people are assigned to a screening or control group for as long as screening would be offered in practice, which in most countries is 20 years. Overdiagnosis would be the difference in number of cancers detected during the lifetime of the two groups, provided the control group or age groups not targeted are not screened. In the absence of overdiagnosis the initial increase in cancers in the screened age groups would be fully compensated for by a similar decrease in cancers among older age groups no longer offered screening, as these cancers would already have been detected.

The extent of overdiagnosis and overtreatment as a result of mammography screening was first quantified in reviews of randomised trials.5 6 The total number of mastectomies and lumpectomies increased by 31% and mastectomies by 20%.6 As these trials did not have lifelong follow-up the extent of overdiagnosis could have been overestimated. Underestimation is also possible, however, as the randomised design was maintained for only 4-9 years6 and as opportunistic screening occurred in the control groups.7

Screening programmes differ from randomised trials. Radiologists outside a rigorous trial setting may be less well trained than those in the trial, and technical developments resulting in higher resolution images may also affect outcomes. The basic premise of an unchanged lifetime risk of breast cancer in the absence of overdiagnosis is, however, the same.

To estimate the extent of overdiagnosis in organised screening programmes we compared trends in breast cancer incidence before and after screening, taking account of changes in the background incidence and any compensatory drop in incidence of breast cancer among older, previously screened women. We combined our results in a meta-analysis.

Methods

We included articles in any language with data on breast cancer incidence for both screened and older, non-screened age groups for at least seven years before screening and seven years after screening had been fully implemented, regardless of the time it took to implement screening. We reasoned that a long period after implementation was necessary to obtain an estimate of the trend in breast cancer incidence that was unaffected by the initial peak in prevalence when screening is introduced. Acquiring incidence data for age groups older than those screened allowed us to evaluate any compensatory declines in incidence among previously screened women.

When a country was described in several papers we selected the one with the most recent and best reported data as our core article, and we supplemented with other papers when relevant. When possible we also added data from the internet and supplied by authors. We did not search for articles published before 1990, as insufficient time would have elapsed after the initiation of screening.

Literature searches

Our searches in PubMed were developed iteratively and we tried several search strings. The final search, which identified all included articles, was: ((“Mammography”[MeSH] OR “Mass Screening”[MeSH]) AND ((“Breast Neoplasms/epidemiology”[MeSH]) OR (“Breast Neoplasms”[MeSH] AND incidence*[ti]))) OR (Breast cancer AND screening AND trend*[ti]) OR (Breast cancer AND screening AND overdiagnos*[ti]).

One author scanned titles and abstracts and retrieved the full text of potentially relevant articles for evaluation of eligibility, scanned the reference lists, and contacted authors. We compared the final search with an archive of all articles on breast cancer screening published in 2004, which we have used for another study,8 and found that we had not missed any potentially relevant papers. None of the four authors we contacted told us of additional studies but three provided unpublished data or referred us to internet resources.9 We did not find additional studies in the reference lists.

Data extraction

Both authors extracted data independently, with differences resolved by discussion. We extracted data on population size, screening uptake, length of time before and after the implementation of screening, and incidence of breast cancer for both screened and non-screened age groups. If data on carcinoma in situ were missing, we estimated overdiagnosis with these cases included, assuming that they would contribute 10% of the diagnoses in a population offered screening10 11—that is, we divided the incidence of invasive cancers by 0.9.

Selection of last prescreening year

The last prescreening year was usually the year before formal implementation of screening. If the levels of invasive breast cancer or carcinoma in situ appeared to increase abruptly in the years immediately before the introduction of screening, however, we excluded these years from estimates of trends before screening. Carcinoma in situ is rarely diagnosed without screening and such increases indicate opportunistic screening (screening outside the organised programme). Similarly, abruptly increased rates of invasive breast cancer immediately before formal implementation of screening likely indicate pilot programmes or extensive opportunistic screening.

Calculation of overdiagnosis in absence of compensatory drop

We used simple linear regression to estimate trends as we could not use Poisson regression because the denominators for the reported rates of breast cancer were not available. To compensate for changes in background incidence in the screened age group we carried out a linear regression analysis of the prescreening years and extended this regression line to the last observation year. We used the calculated value for this year to estimate what the expected incidence would have been in the absence of screening.

We did another linear regression analysis for the screened age group but used the observed incidence in that part of the screening period where the programme was fully implemented and past any prevalence peak. This was done to take account of annual fluctuations. The rate ratio between the result for the last observation year determined by linear regression and the expected incidence in that year (that is, the observed incidence in the last observation year divided by the expected incidence in the last observation year) constituted our estimate of overdiagnosis.

Calculation of overdiagnosis in presence of compensatory drop

In the age group that exceeded the age for screening, we studied whether the observed increase in the incidence of breast cancer in the screening period was lower than the expected increase, in both cases using linear regression. If this was the case, we considered that the difference between the observed and expected incidence was due to a compensatory drop. We calculated the size of this drop as a rate ratio, as above, using the last observation year.

From this rate ratio we calculated the absolute number of breast cancer cases per 100 000 women that corresponded to the drop in the older age groups (X). Similarly, for the screened age groups we calculated the number of extra cases of breast cancer (those above the expected number) per 100 000 women that corresponded to the increase (Y). We compensated for the many more women in the younger, screened age group (A) than in the older age group of previously screened women (B) using official population statistics to calculate a correction factor C=A/B.

We calculated (Y×C−X)/(Y×C), which is the percentage of breast cancer cases uncompensated for of the total percentage increase in incidence among screened women. Overdiagnosis was then the observed percentage increase in incidence multiplied by the percentage of uncompensated for breast cancers (see Manitoba under Results for a numerical example).

Women too young to be screened

If available we used the group of women who were too young to be screened as a control to see if our extrapolated prescreening trend for the screened age group was a reasonable estimate of the background incidence, if screening had not been introduced. We did a linear regression analysis using the prescreening incidence, extrapolated the trend into the screening period, as for the other age groups, and compared with the observed incidence.

Meta-analysis

We combined the estimates using Comprehensive Meta Analysis version 2.2.046 (random effects model). As we estimated overdiagnosis using only the last observation year, our estimate has wider confidence intervals than if we had used several observation years. We used population sizes and age distributions obtained from internet sources9 or as provided by the authors.

Results

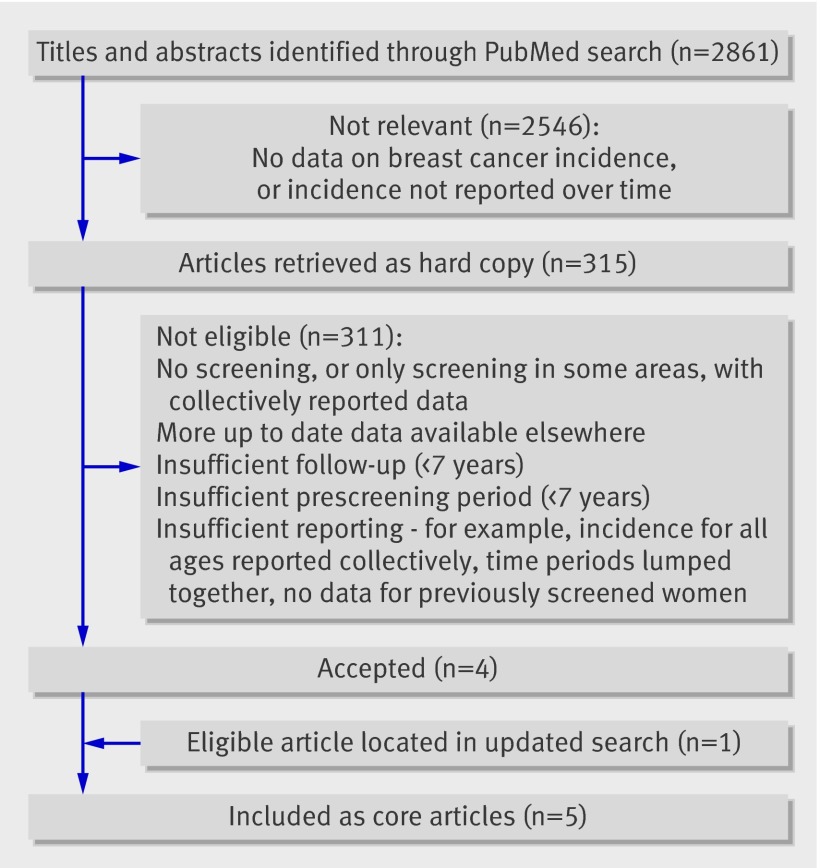

The PubMed search (May 2006) yielded 2861 titles, 2546 of which were not relevant (fig 1). The full text of the remaining 315 articles was evaluated for eligibility. Four were included as core articles and one was added when the search was updated in April 2007, presenting data from the United Kingdom; Manitoba, Canada; New South Wales, Australia; Sweden; and parts of Norway (table).12 13 14 15 16 (See web extra for data from an additional eight countries and reasons for exclusion.)

Fig 1 Selection of core articles

Overview of individual estimates of overdiagnosis for invasive breast cancer, excluding cases of carcinoma in situ except for Manitoba, Canada

| Variables | United Kingdom | Manitoba, Canada | New South Wales, Australia | Sweden | Norway (AORH counties) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period for estimation of prescreening trend | 1971-84 | 1970-8 | 1972-87 | 1971-85 | 1980-94 |

| Selection method for last prescreening year | Opportunistic screening starts | Opportunistic screening starts | Last year before screening | Last year before screening | Last year before screening |

| Period for estimation of postscreening trend | 1993-9 | 1995-2005 | 1996-2002 | 1998-2006 | 2000-6 |

| Breast cancer incidence in final year of observation (per 100 000 women) | |||||

| Screened age group: | |||||

| Observed (regression analysis) | 278 | 318/375* | 291 | 328 | 303 |

| Expected (regression analysis) | 197 | 236/236* | 211 | 242 | 213 |

| Observed/expected | 1.41 | 1.35/1.59 | 1.38 | 1.35 | 1.42 |

| Exceeded age for screening: | |||||

| Observed (regression analysis) | 278 | 401/442* | 317 | 303 (1998) | 246 |

| Expected (regression analysis) | 277 | 498/522* | 289 | 338 (1998) | 289 |

| Observed/expected | 1.01 | 0.81/0.85 | 1.10 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| Compensatory drop | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Overdiagnosis (%) with CIS | NA | 44 | NA | NA | NA |

| Estimated overdiagnosis (%), assuming 10% CIS | 57 | 53 | 46 | 52 | |

AORH=Akershus, Oslo, Rogaland, and Hordaland; NA=not available; CIS=carcinoma in situ.

*Without/with CIS.

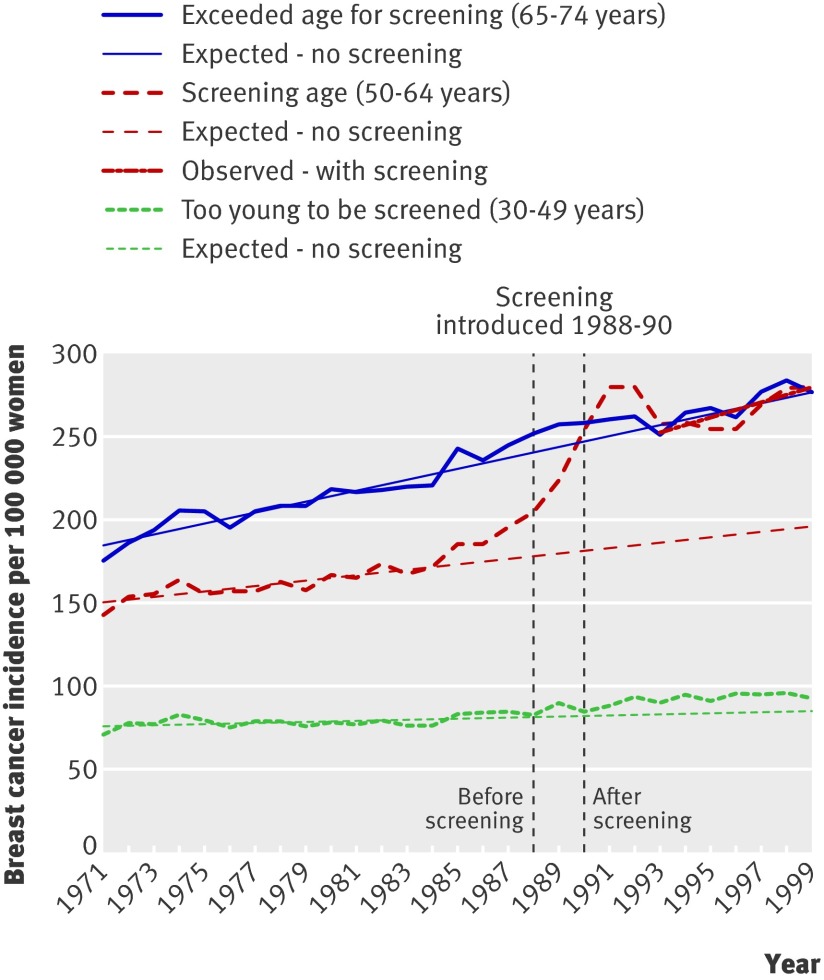

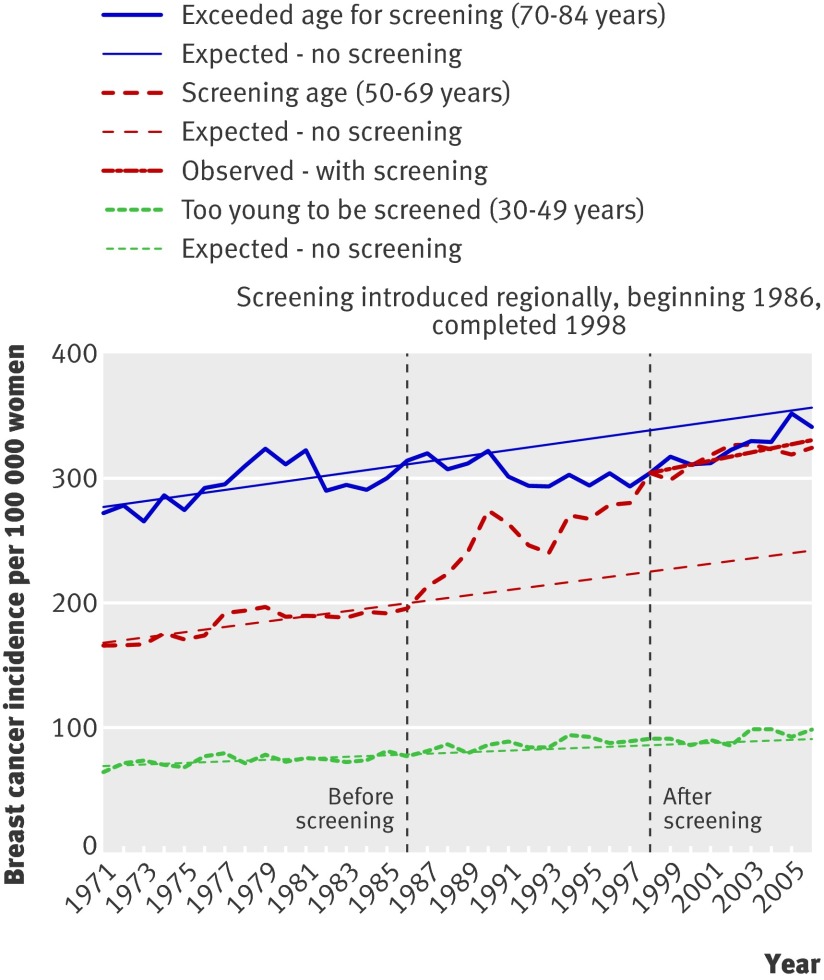

United Kingdom

Screening started in the UK in 1988 for women aged 50-64, with national coverage by 1990, and was expanded to women aged 65-70 in 2002.17 Data from England and Wales covered 1971-99 in graphs with five year age groups.12 These data were combined and the prescreening period defined as 1971-84, before opportunistic screening had influenced the background incidence (fig 2). The period 1993-9 was used to estimate the most recent trend. The increase in incidence of invasive cancer in women aged 50-64 was 41% above the expected rate, interpreted as overdiagnosis as there was no compensatory drop in the older age groups (fig 2). The incidence in younger age groups (30-49 years) increased by 7% over expected rates and in older age groups (65-74 years) by 1% over expected rates. No data were available for carcinoma in situ, but assuming that 10% of the diagnoses in a population offered screening are for carcinoma in situ,10 11 overdiagnosis would be 57% (table).

Fig 2 Incidence of invasive breast cancer per 100 000 women in UK

More recent data (1995-2003) have been published,17 but only for screened age groups. Incidence continues to increase.

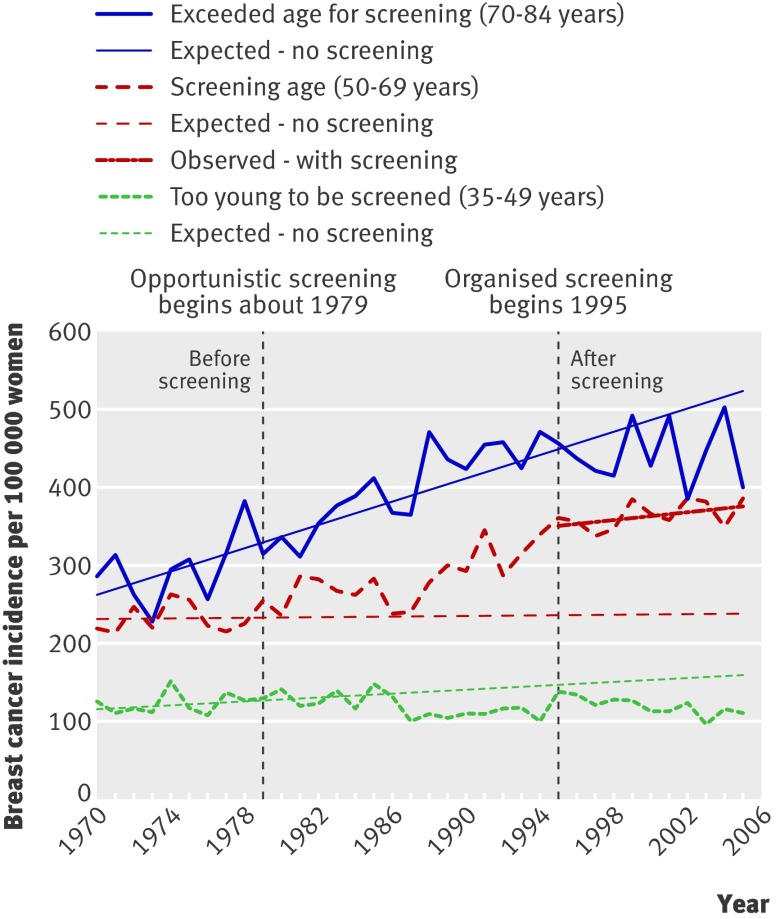

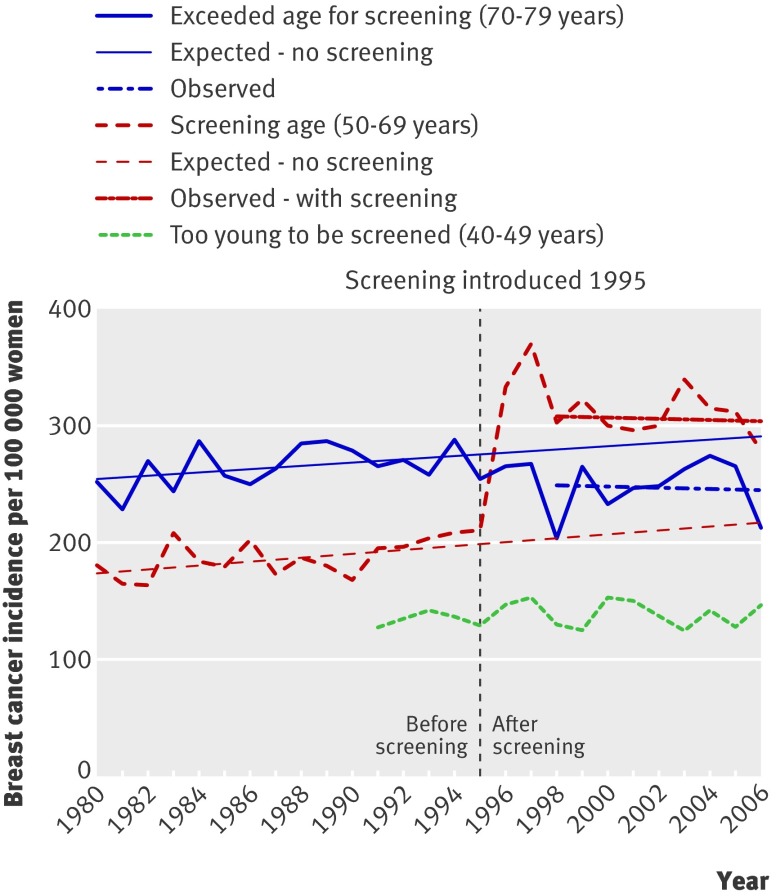

Manitoba, Canada

No national data were found for Canada. In Manitoba, elective screening has been available since the late 1970s, with formal implementation in 1995 for women aged 50-69.13 A study compared incidence up to 1999.13 More recent data were received from the author (fig 3). As the incidence of carcinoma in situ started to increase in 1979, corresponding to the availability of elective screening, the prescreening period was defined as 1970-8. The period 1995-2005 was used to estimate the trend after screening. In the invited age group the incidence for invasive cancer was 35% above the expected rate, and when carcinoma in situ was included it was 59% higher. The total rate for the age group 70-84 was 15% below expected, but for the age group 35-49 it was 32% below expected, which suggests that causes other than screening could have contributed to the drop among previously screened women.

Fig 3 Incidence of invasive breast cancer and carcinoma in situ per 100 000 women in Manitoba, Canada

In the last observation year the 59% increase (including carcinoma in situ) in women aged 50-69 corresponds to 140 extra breast cancer diagnoses per 100 000 women, and the 15% decline in women aged 70-84 corresponds to 80 fewer breast cancer diagnoses per 100 000 women. In Manitoba, 2.3 times as many women are aged 50-69 than are aged 70-84,9 and 75% (=(140×2.3-80)/(140×2.3)) of the increase is therefore uncompensated. A conservative estimate of overdiagnosis is therefore 59%×75%=44%.

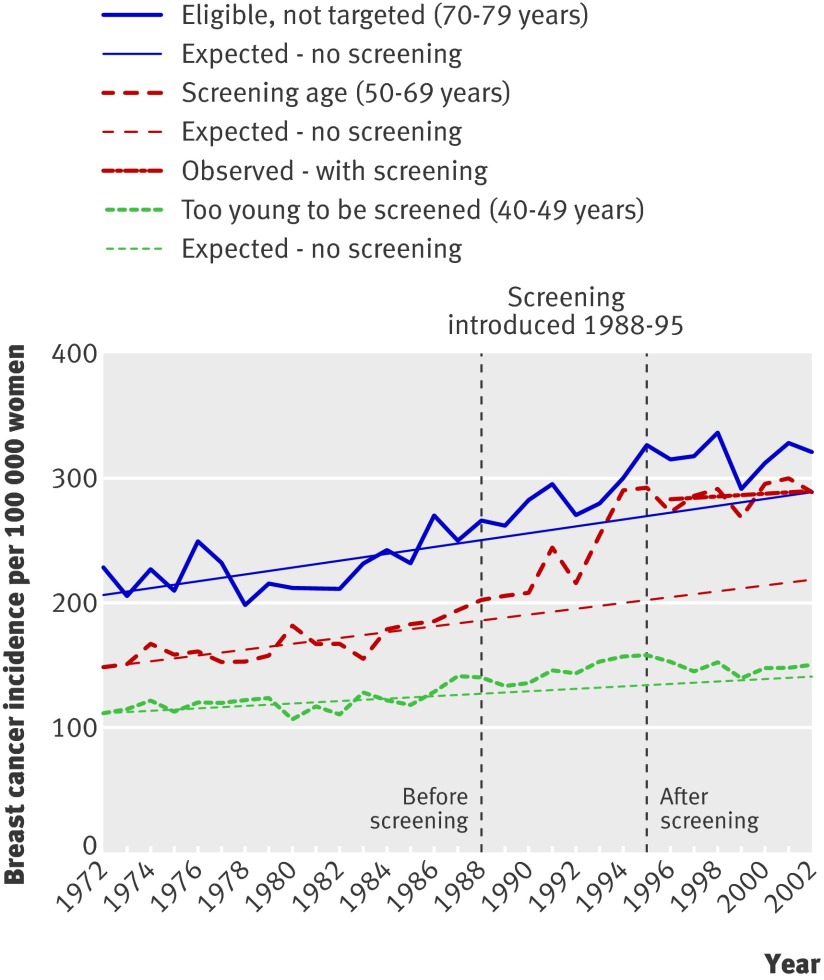

New South Wales, Australia

National data on prescreening rates were not presented for Australia.18 The introduction of screening varied from state to state, and follow-up was short.

For New South Wales, where screening was introduced during 1988-95, a graph showed an increase of 55% for invasive cancer over expected rates in women aged 50-69.14 When the prescreening period was defined as 1972-87 and the period 1996-2002 was used to estimate the trend after screening, this age group showed an increase of 38% over expected rates (fig 4). Among women too young to be screened the increase in incidence was constant (fig 4). Women aged more than 70 were eligible but not targeted. No compensatory drop was observed; the incidence was in fact larger than expected. Overdiagnosis including carcinoma in situ was therefore estimated at 53% (table).

Fig 4 Incidence of invasive breast cancer per 100 000 women in New South Wales, Australia

A similar development was seen in South Australia, but the prescreening period was indicated as one data point, which precluded estimation of prescreening trends.19

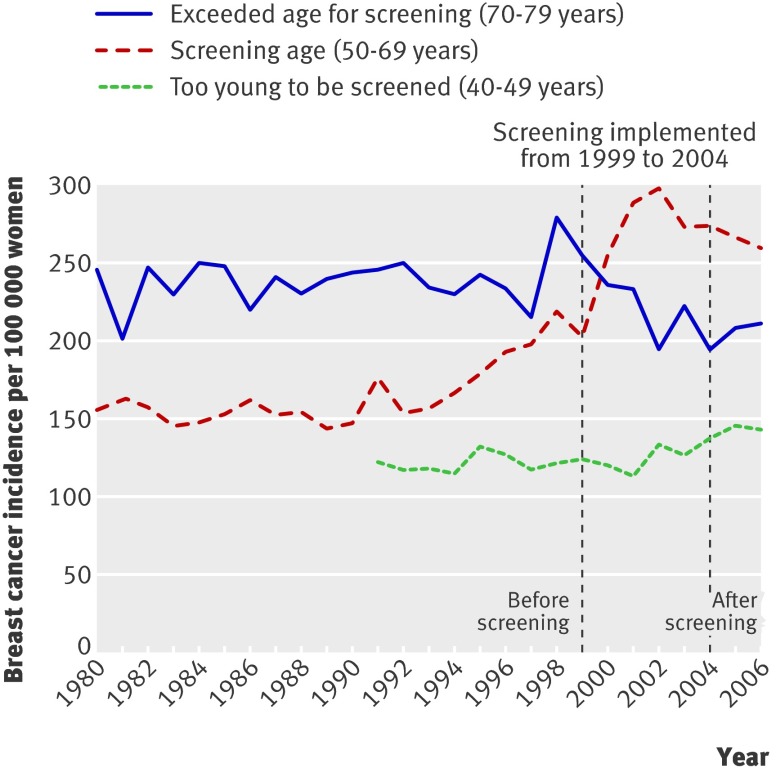

Sweden

Women in a few areas of Sweden participated in screening trials from 1969; nationwide screening started in 1986, and in 1998 almost all eligible women had been offered screening.20 For various counties in 1999, eight different targeted age ranges were described20; the broadest was 40-74 years and the most common was 50-69 years. A study reported an increase in invasive cancer after screening of 69% above expected rates in women aged 50-59 and 27% in women aged 60-69.15 After adjustment for lead time, with estimates varying from 1.6 to 3.0 years, the increases in 2000 were 54% and 21%, respectively.15 Another report21 showed similar increases, without a compensatory drop in older age groups, whereas a third report noted a drop in incidence of 12% in those aged more than 75, and no change for women aged 70-74.22

Data up to 2006 were received from one of the authors (fig 5).22 The meta-analysis focused on the age group 50-69, as this is the only group offered screening in all regions. Using the prescreening period as 1971-85 and the period 1998-2006 to estimate the trend after screening, the estimated increase for invasive cancer over expected rates was 35%, or 86 additional breast cancers per 100 000 women in the last observation year. A constant increase in incidence was seen among women too young to be screened (fig 5). A drop occurred among women aged 70-84, but incidence approached the expected rate at the end of the observation period (fig 5). In the middle of the interval after screening had started in 1998, 10% fewer invasive breast cancers were detected than expected, or 35 fewer cancers per 100 000 women. Eighty eight per cent of the increase was therefore uncompensated. Despite using data when the compensatory decline was largest (rather than from the last observation year), this adjustment only changed the estimate of overdiagnosis for invasive breast cancer from 35% to 31%. When carcinoma in situ was included overdiagnosis was 46% (table).

Fig 5 Incidence of invasive breast cancer per 100 000 women in Sweden

Norway

Screening was introduced in Norway in 1995-6 for women aged 50-69, but only in 40% of the population (Akershus, Oslo, Rogaland, and Hordaland counties; fig 6), and in the rest of Norway from 1999, gaining national coverage in 2004 (fig 7).16 Attendance was good (75-77%).16 22 As screening was fully implemented in the other counties in 2004, overdiagnosis was not estimated for these areas, although the data are presented graphically for comparison (fig 7). In Akershus, Oslo, Rogaland, and Hordaland, a peak in prevalence for invasive breast cancer was followed by stable levels, above prescreening rates in the screened age group.16 22 Screening is generally offered to women aged 50-69, but about 50% of those aged 70-74 were probably screened,23 and incidence initially increased by 30% in this age group and then decreased to prescreening levels. The incidence in women aged 20-50 and more than 74 was stable. Another study reported similar increases but had shorter follow-up.22

Fig 6 Incidence of invasive breast cancer per 100 000 women in Akershus, Oslo, Rogaland, and Hordaland counties in Norway

Fig 7 Incidence of invasive breast cancer per 100 000 women in counties other than Akershus, Oslo, Rogaland, and Hordaland in Norway

Additional data were received from one of the authors.22 The age group 50-69 years was considered as screened. The prescreening period was defined as 1980-94 and the period 2000-6 was used to estimate the trend after screening. The increase in invasive breast cancer was estimated as 42% above expected rates, or 90 additional breast cancers per 100 000 women in the last observation year. Among women too young to be screened the increase in incidence was constant, but data for this group were only available divided into counties from 1991 (fig 6). A 15% drop was seen among women aged 70-79, but a similar drop was also observed in the rest of Norway before screening was fully implemented (fig 7). The drop was conservatively considered as compensatory. The 15% fewer invasive breast cancers correspond to 43 fewer cancers per 100 000 women. This means that 86% of the increase was uncompensated for, or that overdiagnosis was 37%. When carcinoma in situ was included overdiagnosis was 52% (table).

Meta-analysis

The total overdiagnosis of breast cancer in publicly available mammography screening programmes (including carcinoma in situ) was 52% (95% confidence interval 46% to 58%; fig 8). Heterogeneity was moderate (I2=59%).

Fig 8 Meta-analysis of overdiagnosis of breast cancer (including carcinoma in situ) in publicly available mammography screening programmes

Discussion

In populations offered organised screening for breast cancer, overdiagnosis (the detection of cancers that do not cause death or symptoms) was 52%. Carcinoma in situ was included in this estimate, as it is generally treated in the same way as invasive breast cancer1 2 24; the overdiagnosis for invasive breast cancer only was 35% (95% confidence interval 29% to 42%).

We took account of the increasing background incidence by comparing the observed rates of breast cancer with the expected rates for the last year of observation, using projected incidence rates from prescreening trends. Our assumption of a constant, linear increase in the background incidence was supported by data from age groups that were too young to be screened, as agreement between projected and observed rates was good (figs 2-5). Another indication that our assumption was reasonable is that the incidence of breast cancer only deviated from a linear increase around the time of the introduction of screening. This was the case in all included areas, even though screening was introduced at different times (from 1979 in Manitoba to 1995 in Norway). It is therefore unlikely that changes in risk factors or cohort effects could explain the non-linear increases in incidence of breast cancer that occurred with the introduction of screening.

Manitoba had substantial opportunistic screening before organised screening was introduced,13 but we avoided this bias by estimating the prescreening trends from periods when there were few diagnoses of carcinoma in situ.

The trend after implementation of screening was estimated under the assumption that screening leads to a higher incidence level that increases at about the same rate as the background incidence did before screening.25 Our data support this assumption (figs 2-6).

As we have data on long follow-up it is unlikely that the increasing incidence in the screened age group will be compensated for later on. Screening theory implies that a compensatory drop would be apparent shortly after women leave the screening programme and thus after comparatively short follow-up.25

Not all women in all areas passed from the screened age group to the previously screened age group within our observation period. In England and Wales, however, practically all women aged 65-74 would have been offered screening previously at the end of our observation period, but we did not find a compensatory drop in incidence of breast cancer (fig 2).

Some authors use statistical models to adjust their estimate of overdiagnosis for lead time (increased incidence because of advancement of the time of diagnosis).26 27 28 29 30 This approach is problematic as all models carry a high risk of bias31 because they are based on unverified assumptions, and as the choice of variables is crucial—for example, high estimates of lead time result in low estimates of overdiagnosis.31 Estimates of lead time varied between 1.6 and 4 years and even differed in articles by the same authors.15 26 27 29 30

The recent decline in the use of hormone replacement therapy after evidence that it causes breast cancer32 is a possible explanation for the reduction in incidence observed in the United States from 2002, in particular as such a decline did not occur in women below 50 years of age.33 We did not, however, see similar declines in the countries we examined, and the declining use of mammography screening in the United States has also been suggested as an explanation.34

In Norway the effect of screening was separated from that of hormone replacement therapy use, as incidence trends in regions with and without screening could be compared at the same calendar times. Although use of hormone replacement therapy is likely to be similar, a noticeable increase occurred in invasive cancer with the introduction of screening, both in the Akershus, Oslo, Rogaland, and Hordaland counties and in the remaining counties of Norway (figs 6 and 7), and in the other regions we examined (figs 2-4).

Conclusion

We estimated 52% overdiagnosis of breast cancer in a population offered organised mammography screening—that is, one in three breast cancers is overdiagnosed.

What is already known on this topic

Screening for cancer detects inconsequential cancers and leads to overdiagnosis and overtreatment

A Cochrane review of the randomised trials of mammography screening documented 30% overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis in publicly organised mammography screening programmes has not been evaluated systematically

What this study adds

Overdiagnosis of breast cancer in a population offered organised mammography screening was 52%

This extent of overdiagnosis equates to one in three breast cancers being overdiagnosed

We thank Alain Demers (Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Registry, CancerCare Manitoba) for supplying data for Manitoba, Per-Henrik Zahl (Folkehelseinstituttet, Oslo) for supplying data for Sweden and Norway, and Gilbert Welch for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Contributors: PCG and KJJ conceived the study, developed the methods, extracted data and carried out the analyses. KJJ did the searches, contacted authors, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was revised by PCG. Both authors are guarantors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2587

References

- 1.Vainio H, Bianchini F. IARC handbooks of cancer prevention vol 7: breast cancer screening. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002.

- 2.Welch GH. Should I be tested for cancer? California: University of California Press, 2004.

- 3.Nielsen M, Thomsen JL, Primdahl S, Dyreborg U, Andersen JA. Breast cancer atypia among young and middle-aged women: a study of 110 medicolegal autopsies. Br J Cancer 1987;56:814-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch HG, Black WC. Using autopsy series to estimate the disease “reservoir” for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gøtzsche PC, Olsen O. Is screening for breast cancer with mammography justifiable? Lancet 2000;355:129-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD001877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson I, Aspegren K, Janzon L, Landberg T, Lindholm K, Linell F, et al. Mammographic screening and mortality from breast cancer: the Malmö mammographic screening trial. BMJ 1988;297:943-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jørgensen KJ, Klahn A, Gøtzsche PC. Are benefits and harms in mammography screening given equal attention in scientific articles? A cross-sectional study. BMC Med 2007;5:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics Canada. 2008. www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/topics/RetrieveProductTable.cfm?Temporal=2006&PID=88984&GID=838031&METH=1&APATH=3&PTYPE=88971&THEME=66&AID=&FREE=0&FOCUS=&VID=0&GC=99&GK=NA&RL=0&TPL=RETR&SUB=0&d1=0.

- 10.Lindgren A, Holmberg L, Thurfjell E. The influence of mammography screening on the pathological panorama of breast cancer. APMIS 1997;105:62-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS. Screening for breast cancer in England: past and future. Publication No 61. Department of Health: NHS cancer screening programmes, 2006. www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbsp61.html.

- 12.Johnson A, Shekhdar J. Breast cancer incidence: what do the figures mean? J Eval Clin Pract 2005;11:27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demers AA, Turner D, Mo D, Kliewer EV. Breast cancer trends in Manitoba: 40 years of follow-up. Chronic Dis Can 2005;26:13-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu C, Morrell S, Page A, Rickard M, Brassil A, Taylor R. Population-based mammography screening and breast cancer incidence in New South Wales, Australia. Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:153-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonsson H, Johansson R, Lenner P. Increased incidence of invasive breast cancer after the introduction of service screening with mammography in Sweden. Int J Cancer 2005;117:842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofvind S, Sorum R, Haldorsen T, Langmark F. [Incidence of breast cancer before and after implementation of mammography screening]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2006;126:2935-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre. Breast screening programme, England: 2004-05. www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/breast-statistics-bulletin-2004-05.pdf.

- 18.Giles G, Amos A. Evaluation of the organised mammographic screening programme in Australia. Ann Oncol 2003;14:1209-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luke C, Priest K, Roder D. Changes in incidence of in situ and invasive breast cancer by histology type following mammography screening. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006;7:69-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjönell G, Ståhle L. [Health checks with mammography do not reduce breast cancer mortality]. Läkartidningen 1999;96:904-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemminki K, Rawal R, Bermejo JL. Mammographic screening is dramatically changing age-incidence data for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4652-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahl PH, Strand BH, Mæhlen J. Incidence of breast cancer in Norway and Sweden during introduction of nationwide screening: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2004;328:921-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Møller B, Weedon-Fekjær H, Hakulinen T, Tryggvadottir L, Storm HH, Talback M, et al. The influence of mammographic screening on national trends in breast cancer incidence. Eur J Cancer Prev 2005;14:117-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Douek M, Baum M. Mass breast screening: is there a hidden cost? Br J Surg 2003;90:44-5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boer R, Warmerdam P, de Koning H, van Oortmarssen G. Extra incidence caused by mammographic screening. Lancet 1994;343:979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svendsen AL, Olsen AH, von Euler-Chelpin M, Lynge E. Breast cancer incidence after the introduction of mammography screening: what should be expected? Cancer 2006;106:1883-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paci E, Miccinesi G, Puliti D, Baldazzi P, De Lisi V, Falcini F, et al. Estimate of overdiagnosis of breast cancer due to mammography after adjustment for lead time. A service screening study in Italy. Breast Cancer Res 2006;8:R68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen AH, Jensen A, Njor SH, Villadsen E, Schwartz W, Vejborg I, et al. Breast cancer incidence after the start of mammography screening in Denmark. Br J Cancer 2003;88:362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsen AH, Agbaje OF, Myles JP, Lynge E, Duffy SW. Overdiagnosis, sojourn time, and sensitivity in the Copenhagen mammography screening program. Breast J 2006;12:338-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paci E, Warwick J, Falini P, Duffy SW. Overdiagnosis in screening: is the increase in breast cancer incidence rates a cause for concern? J Med Screen 2004;11:23-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahl PH, Jørgensen KJ, Mæhlen J, Gøtzsche PC. Biases in published estimates of overdetection due to screening with mammography. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:199-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ, et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorat MA. What caused the decline in US breast cancer incidence? Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2008;5:314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]