Abstract

The abundance of retinoic acid (RA) is determined by the balance between its synthesis by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) and its degradation by CYP26. In particular, the dynamic expression of three CYP26 genes controls the regional level of RA within the body. Pregastrulation mouse embryos express CYP26 but not RALDH. We now show that mice lacking all three CYP26 genes manifest duplication of the body axis as a result of expansion of the Nodal expression domain throughout the epiblast. Mouse Nodal was found to contain an RA-responsive element in intron 1 that is highly conserved among mammals. In the absence of CYP26, maternally derived RA activates Nodal expression in the entire epiblast of pregastrulation embryos via this element. These observations suggest that maternal RA must be removed by embryonic CYP26 for correct Nodal expression during embryonic patterning.

Keywords: CYP26, Nodal, retinoic acid, RA-responsive element, embryonic patterning

The abundance of retinoic acid (RA) in the body is determined mainly by the balance between its synthesis by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) and its degradation by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP26 (Ross et al. 2000; Abu-Abed et al. 2001; Sakai et al. 2001; Duester 2008; Niederreither and Dolle 2008). Mice (and humans) possess three CYP26 genes: Cyp26a1, Cyp26b1, and Cyp26c1 (MacLean et al. 2001; Abu-Abed et al. 2002; Nebert and Russell 2002; Tahayato et al. 2003; Sirbu et al. 2005). Mutant mice lacking each of the three CYP26 genes individually have provided insight into the role of a restricted distribution of RA in various aspects of organogenesis. Cyp26a1 is expressed in the hindbrain and tail bud, and Cyp26a1−/− mice exhibit hindbrain patterning defects and caudal truncation, as do embryos exposed to excess RA (Abu-Abed et al. 2001; Sakai et al. 2001). Cyp26b1 is expressed in the distal region of the developing limb, where RA signaling is absent, and the lack of CYP26B1 results in the expansion of RA signaling toward the distal end of the developing limb and the induction of proximodistal patterning defects (Yashiro et al. 2004; Uehara et al. 2007). RA is a small molecule that can diffuse over a long distance. Transport of RA is also important as domains of RA signaling do not necessarily reflect simple patterns of synthesis and degradation.

One of the earliest roles of CYP26 isozymes in embryogenesis is apparent in anteroposterior (A–P) patterning of the developing brain (Ribes et al. 2007; Uehara et al. 2007). Cyp26a1 and Cyp26c1 are expressed in the anterior region of mouse embryos between embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) and E8.5, whereas Raldh2 and the RARE-hsplacZ transgene (which encodes β-galactosidase under the control of an RA-responsive element (RARE) and the Hsp68 promoter) are expressed in the posterior region. Mouse embryos lacking both Cyp26a1 and Cyp26c1 exhibit expansion of RA signaling toward the anterior side as well as A–P patterning defects of the developing brain. Before E7.5, expression of Raldh2 and RARE-hsplacZ was undetectable, whereas Cyp26a1 was highly expressed (Supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that CYP26-mediated restriction of the spatial distribution of the RA signal may also be required at earlier stages of development, during or even before gastrulation.

To determine the relevance of temporal and spatial regulation of RA signaling, we examined mutant mice that lack all three CYP26 genes. Our observations reveal unexpected roles of CYP26s in embryonic patterning and in regulation of Nodal, which encodes a transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-related protein that itself plays key roles in early embryogenesis.

Results

A–P patterning defects and aberrant Nodal expression in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− mice

Cyp26a1b1c1−/− mice exhibited defects that were more pronounced than those of Cyp26b1−/− or Cyp26a1c1−/− mice and proved lethal during early embryogenesis. At E9.25, 44% (11 out of 25) of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos were markedly deformed, showing complete or partial duplication of the body axis, whereas the remaining embryos exhibited only abnormal patterning in the developing brain, similar to that apparent in most Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos (Uehara et al. 2007). Embryos showing partial or complete duplication of the body axis will hereafter be referred to as “severely affected” (Supplemental Fig. S2), and the phenotype of these embryos will be described unless indicated otherwise. Two sets of neural tubes were observed in these Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos (Fig. 1B′,C′). At E9.0, the expression domain of Shh, which marks the axial midline in wild-type embryos (Fig. 1E′), was completely (Fig. 1F′) or partially (Fig. 1G′) duplicated in the Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos. The Shh expression in the midline was also duplicated at E8.25 (Supplemental Fig. S3B′). Furthermore, the expression domain of T (Brachury), which marks the primitive streak (Fig. 1I′; Supplemental Fig. S3C′), was duplicated partially (Fig. 1J′; Supplemental Fig. S3D′) or completely (Fig. 1K′; Supplemental Fig. S3E′) in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos. These observations thus revealed that Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos manifest duplication of the primitive streak.

Figure 1.

Duplication of the body axis in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− and Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos. (A–D) Lateral views of wild-type (A), Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (B,C), and Cyp26a1/c1−/− (D) embryos at E9.25. The anterior side is on the left. About two-fifths of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (B,C) or one-fourth of Cyp26a1/c1−/− (D) embryos were severely deformed, showing complete or partial duplication of the body axis. (A′–D′) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining of sections of the embryos shown in A through D, respectively. Two sets of neural tubes or grooves (red arrowheads) were apparent in the mutant embryos, compared with the single neural tube (black arrowhead) in the wild-type embryo. The planes of the sections are indicated by the horizontal lines through the embryos in A–D. The boxed region in C′ is shown at higher magnification in C″. Bars, 100 μm. (E–L) Lateral views of wild-type (E,I), Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (F,G,J,K), and Cyp26a1c1−/− (H,L) embryos at E9.0 (E–H) or E8.25 (I–L) that had been subjected to whole-mount in situ hybridization for analysis of the expression of Shh (E–H) or T (Brachury) (I–L). The anterior side is on the left. (E′–L′) Ventral (E′–H′) and posterior (I′–L′) views of the embryos in E–H and in I–L, respectively. The expression domain of Shh was partially or completely duplicated in the mutant embryos (red arrowheads in F′–H′). Mutant embryos expressed T in two distinct primitive streaks (red arrowheads in J′ and L′) or ectopically at the embryonic–extraembryonic boundary (red arrowheads in K′).

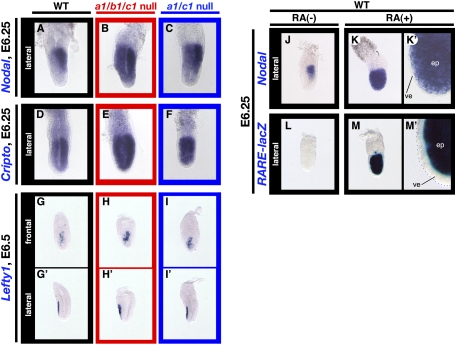

The patterning defects of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos resembled those of mutant mice lacking the Nodal antagonists Lefty1 and Cer1, which also show duplication of the primitive streak as a result of the up-regulation of Nodal activity at the pregastrulation stage (Perea-Gomez et al. 2002). We therefore examined embryonic patterning before gastrulation in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos. Whereas expression of Nodal is restricted to the posterior region of wild-type embryos at E6.0 to E6.25 (Fig. 2A), the Nodal expression domain occupied the entire region of the epiblast in 50% (three out of six embryos) of the Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos examined (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S4B,C). Similarly, whereas expression of Cripto, which encodes a coreceptor for Nodal, is most prominent in the posterior region of the epiblast in wild-type embryos (Fig. 2D), it was up-regulated and extended throughout the epiblast in 57% (four out of seven embryos) of the mutant embryos examined (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. S4G,H). The aberrant expression of Nodal in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos was not due to impaired function of the anterior visceral endoderm (AVE), which appeared to be formed normally. Expression of various AVE markers, including Hex, Dkk1, Cer1, and Lefty1, was thus maintained in the mutant (Fig. 2G,G′,H,H′; Supplemental Fig. S5). The level of Lefty1 expression was increased in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos (Fig. 2G,H), most likely as a result of increased Nodal activity, given that Lefty1 expression in the AVE is regulated by Nodal signaling (Yamamoto et al. 2004). These results thus suggested that expansion of Nodal expression throughout the epiblast of the mutant embryos was not secondary to impaired AVE function but rather was due to dysregulation of Nodal in the epiblast.

Figure 2.

Epiblast patterning defects in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− and Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos. (A–I,G′–I′) Expression of Nodal, Cripto, and Lefty1 in wild-type (A,D,G,G′), Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (B,E,H,H′), and Cyp26a1c1−/− (C,F,I,I′) embryos at E6.25 or E6.5, as indicated, was examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Lateral views with the anterior side on the left are shown, with the exception of the frontal views shown in G–I. Nodal was expressed in the posterior region of the wild-type embryo (A) but was expressed throughout the epiblast of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (B) or Cyp26a1c1−/− (C) embryos. Whereas Cripto expression was most prominent in the posterior region of the epiblast of the wild-type embryo (D), it was up-regulated and extended to the entire epiblast in the mutant embryos (E,F). The expression domain of Lefty1, which marks the AVE in wild-type embryos (G,G′), was maintained in the mutant embryos (H,H′,I,I′), although the level of Lefty1 expression was increased in the mutants (H,I). (J–M,K′,M′) Expression of Nodal (J,K,K′) and the RARE-hsplacZ transgene (L,M,M′) in untreated (J,L) or RA-treated (K,K′,M,M′) wild-type embryos at E6.25 was examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization or staining with the β-galactosidase substrate X-gal. Nodal was expressed in the posterior region of the epiblast in the untreated embryo (J) but was expressed in the entire epiblast of the RA-treated embryo (K,K′). Expression of RARE-hsplacZ was not detected in the untreated embryo (L) but was pronounced throughout the epiblast of the RA-treated embryo (M,M′). The images in K and M are shown at higher magnification in K′ and M′, respectively. (ep) Epiblast; (ve) visceral endoderm.

Role of each CYP26 gene in embryonic patterning

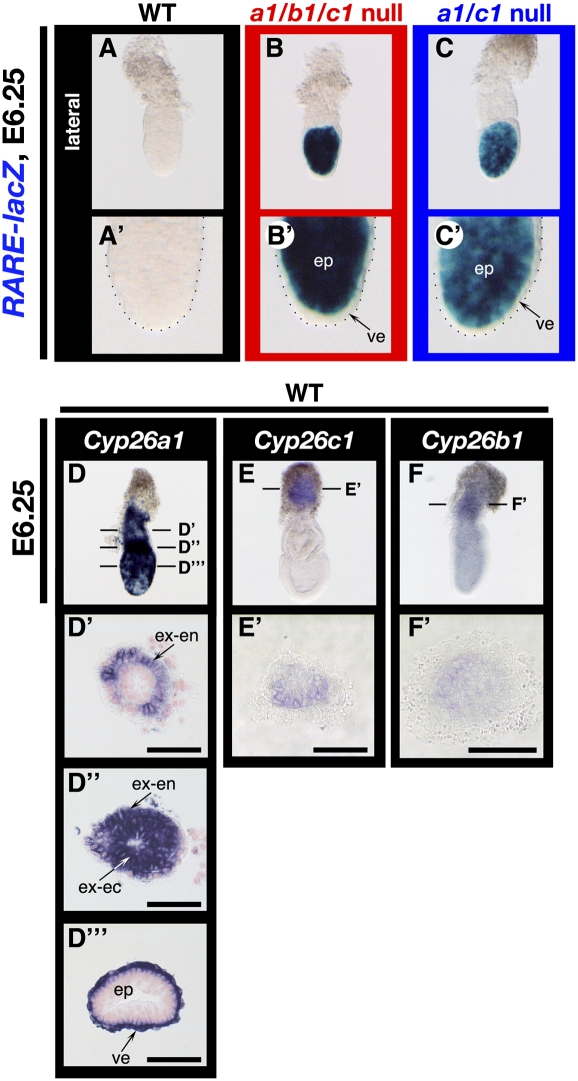

Mice lacking any one of the three CYP26 genes do not exhibit the early patterning defects observed in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos (Abu-Abed et al. 2001; Sakai et al. 2001; Yashiro et al. 2004; Uehara et al. 2007; data not shown). We examined the expression of each CYP26 gene between E5.5 and E6.5. All three genes were found to be expressed in the extraembryonic cell types that surround the embryo proper, although Cyp26a1 was the most prominently expressed gene at these stages. At E5.5 and E6.0, Cyp26a1 was thus highly expressed in the extraembryonic endoderm, extraembryonic ectoderm, and visceral endoderm, domains that surround the embryo proper (Fig. 3D–D′; Supplemental Fig. S1G,J). Cyp26c1 and Cyp26b1 were expressed in a different domain of the extraembryonic region, the ectoplacental cone, albeit at a lower level, with the expression level of Cyp26c1 being higher than that of Cyp26b1 (Fig. 3E,E′,F,F′). These results suggested that Cyp26a1 is the major CYP26 gene expressed at pregastrulation stages, although Cyp26b1 and Cyp26c1 are able to compensate for the loss of Cyp26a1 expression. Furthermore, consistent with the relative levels of Cyp26b1 and Cyp26c1 expression, a substantial proportion (26%, 18 of 70 embryos) of Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos showed gastrulation defects, including partial or complete duplication of the primitive streak (Fig. 1L′; Supplemental Fig. S3F′; Supplemental Table S1), similar to those of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos, whereas Cyp26a1b1−/− embryos did not exhibit such defects (data not shown). Furthermore, a portion of Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos displayed up-regulated expression of Nodal (two out of five embryos) and Cripto (three out of eight embryos) (Supplemental Fig. S4D,E,I,J).

Figure 3.

Contribution of each CYP26 isozyme to RA metabolism in pregastrulation embryos. (A–C,A′–C′) Expression of the RARE-hsplacZ transgene in wild-type (A), Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (B), and Cyp26a1c1−/− (C) embryos at E6.25 as revealed by X-gal staining. Lateral views are shown with the anterior side on the left. Each image is shown at higher magnification in A′–C′, respectively. Expression of the transgene was not detected in the wild-type embryo (A,A′) but was pronounced in the entire epiblast (ep) of the mutants (B,B′,C,C′). (D–F,D′–F′,D″,D″′) Expression patterns of Cyp26a1 (D), Cyp26c1 (E), and Cyp26b1 (F) in wild-type embryos at E6.25 as revealed by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Lateral views are shown with the anterior side on the left. The planes of sections shown in D′, D″, D″′, E′, and F′ are indicated by the horizontal lines through the embryos in D–F. Cyp26a1 was highly expressed in the extraembryonic endoderm (ex-en) (D′,D″), the extraembryonic ectoderm (ex-ec) (D″), and the visceral endoderm (ve) (D′″). Cyp26c1 and Cyp26b1 were expressed in the ectoplacental cone, albeit at a lower level (E,E′,F,F′). Bars, 50 μm.

Consistent with the expression patterns of the CYP26 genes, RA signaling, as revealed by the RA-responsive transgene RARE-hsplacZ, was not detected in wild-type embryos at E6.25 (Figs. 2L, 3A,A′) but was pronounced in the entire epiblast of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− (four out of eight) and Cyp26a1c1−/− (five out of 12) embryos (Fig. 3B,B′,C,C′).

Expansion of Nodal expression in the epiblast is responsible for the embryonic patterning defects in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos

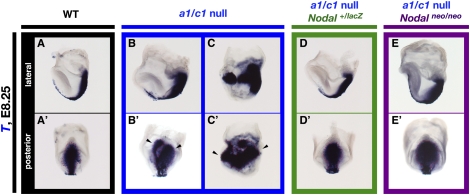

We next examined whether the expansion of Nodal expression in the epiblast is responsible for the observed patterning defects in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos. If such is the case, a reduction in the extent of Nodal expression would be expected to rescue the gastrulation defects of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− and Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos. We first examined the effect of the removal of one copy of Nodal by comparing the phenotypes of Nodal+/+, Cyp26a1c1−/−, and Nodal+/lacZ, Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos (Fig. 4). NodallacZ is a null allele, in which exon 1 of Nodal gene is replaced by lacZ (Collignon et al. 1996). Whereas 26% (18 out of 70) of the former embryos showed duplication of the body axis (Supplemental Table S1), only 6% (one out of 16) of the latter embryos did so at E8.25. We also examined the effect of a hypomorphic Nodal allele (Nodalneo). Nodalneo/neo embryos develop left–right patterning defects at E8.0 as a result of a marked reduction in the level of Nodal expression in the node (Saijoh et al. 2003). Nodal expression is also reduced in the epiblast at E6.5, but not as severely as in the node at E8.0 (Supplemental Fig. S6), which permits the Nodalneo/neo embryo to undergo normal gastrulation. None of the Nodalneo/neo, Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos examined at E8.25 (zero out of seven embryos) showed the embryonic patterning defects (Fig. 4E′) apparent in 35% of Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos (Supplemental Table S1). (For these experiments, mice were maintained on a special diet CRF that contains ∼30% higher vitamin A than a conventional diet) (see the Materials and Methods.) Finally, three Cyp26a1b1c1−/−, Nodal+/lacZ embryos that were recovered at E8.75 showed normal Shh expression in the midline (Supplemental Fig. S7B,B′). These results thus indicated that dysregulation of Nodal expression in the epiblast is responsible for the abnormal patterning of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos.

Figure 4.

Rescue of embryonic patterning defects in Nodal+/lacZ, Cyp26a1c1−/− and Nodalneo/neo, Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos. (A–E,A′–E′) Expression of T (Brachury) in wild-type (A,A′), Cyp26a1/c1−/− (B,B′,C,,C′), Nodal+/lacZ, Cyp26a1c1−/− (D,D′), and Nodalneo/neo, Cyp26a1c1−/− (E,E′) embryos at E8.25 was examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Lateral views with the anterior side on the left are shown in A through E, and posterior views are shown in A′ through E′. Exon 1 of Nodal is replaced by lacZ in the NodallacZ allele. Whereas ∼35% of Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos expressed T in two distinct primitive streaks (arrowheads in B′) or ectopically at the embryonic–extraembryonic boundary (arrowheads in C′), only 6% of the Nodal+/lacZ, Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos (not shown) did so. (E′) Furthermore, none of the Nodalneo/neo, Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos showed the embryonic patterning defects.

An RARE within the autoregulatory enhancer regulates Nodal expression in the epiblast

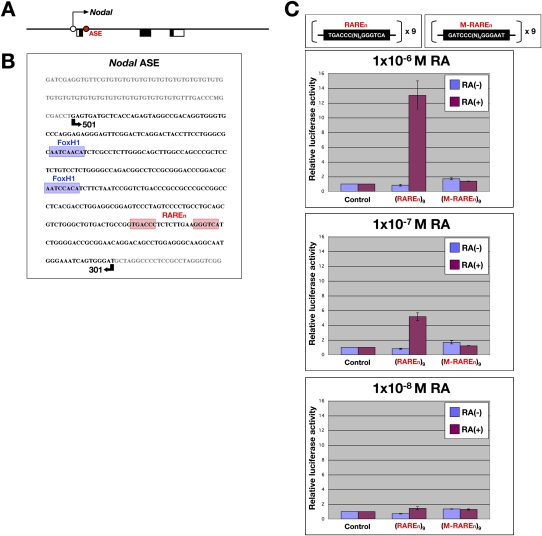

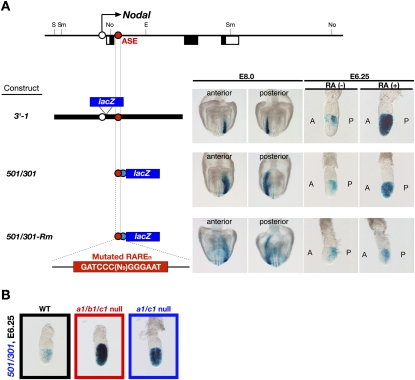

The patterning defects of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos suggested that Nodal expression in the epiblast might be directly controlled by RA and that an increased RA level in the epiblast of the mutant embryos may be responsible for up-regulation of Nodal expression. We found that such was the case. First, administration of exogenous RA to wild-type embryos at E6.0 induced expression of the RARE-hsplacZ transgene (Fig. 2M,M′) and Nodal (Fig. 2K,K′) throughout the epiblast, as observed for Nodal in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos (Fig. 2B). Second, expression of Nodal in the epiblast was found to be regulated by an RARE. A Nodal-responsive enhancer (referred to as ASE) located in intron 1 of Nodal contains a RARE-like sequence, TGACCCN9GGGTCA (hereafter referred to as RAREn), in addition to two FoxH1-binding sequences (Fig. 5A,B). While other RAREs have 1, 2, or 5 nucleotides (nt) between the two RXR-binding sites (Umesono et al. 1991), RAREn has 9 nt. ASE regulates Nodal expression in the epiblast at E6.0 to E6.5 as well as in the left lateral plate at E8.0 (Adachi et al. 1999; Norris and Robertson 1999). To examine whether RAREn responds to RA, we monitored expression of two lacZ transgenes: 3′-1, in which lacZ expression is driven by the lacZ promoter and a 3-kb genomic region containing ASE (Fig. 6A; Adachi et al. 1999) and 501/301 in which lacZ expression is driven by the heterologous Hsp68 promoter and a 200-base-pair (bp) region of ASE (Fig. 6A; Adachi et al. 1999). The RAREn sequence is included in both transgenes. Like Nodal, both lacZ transgenes were found to be expressed in the posterior region of the epiblast in wild-type embryos at E6.25 (Fig. 6A). However, administration of exogenous RA resulted in the expression of both transgenes in the entire epiblast (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, expression of the 501/301 transgene was markedly up-regulated in Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos (Fig. 6B). Mutation of the TGACCCN9GGGTCA sequence in the ASE of the 501/301 transgene to GATCCCN9GGGAAT (giving rise to the 501/301-Rm transgene) did not affect the expression pattern in wild-type embryos in the absence of exogenous RA; the mutant transgene was thus expressed in the posterior epiblast at E6.25 and the left lateral plate at E8.0 (Fig. 6A). However, 501/301-Rm failed to respond to exogenous RA administered at E6.0 (Fig. 6A). These results thus suggested that transcription of Nodal in the epiblast is controlled directly by RA signaling through RAREn in the ASE. A luciferase reporter assay performed with RA-responsive mouse embryonal carcinoma (P19) cells revealed that a reporter construct containing tandem repeats of TGACCCN9GGGTCA, but not one containing the mutated sequence GATCCCN9GGGAAT, responded to RA in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5C). These results thus supported the notion that RAREn indeed functions as an RARE.

Figure 5.

Direct regulation of Nodal expression by RA through an RARE in intron 1. (A) Localization of the ASE in intron 1 of Nodal. The arrow indicates the direction of transcription; open and closed boxes denote noncoding and coding regions of exons, respectively; the ASE is depicted by the red circle. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the Nodal ASE, which contains a RARE-like sequence, TGACCCN9GGGTCA (RAREn, red shading), in addition to two FoxH1-binding sequences (FASTs, blue shading). The region included in the 501/301 transgene (see Fig. 6A) is indicated by the arrows. (C) Luciferase reporter assay performed with P19 cells transiently transfected with reporter constructs containing tandem repeats of TGACCCN9GGGTCA [(RAREn)9] or the mutated sequence GATCCCN9GGGAAT [(M-RAREn)9] and treated with the indicated concentrations of RA or with dimethyl sulfoxide as vehicle. Data are means of triplicates from a representative experiment.

Figure 6.

Nodal as a target of RA signaling in pregastrulation embryos. (A) Structure of three lacZ constructs and their expression in mouse embryos. (E) EcoRI; (No) NotI; (S) SalI; (Sm) SmaI. The open black and closed blue circles indicate the proximal promoter of Nodal and the Hsp68 promoter, respectively. Staining with X-gal revealed that both 3′-1 and 501/301 transgenes were expressed in the posterior region of the epiblast (at E6.25) and in the left lateral plate (at E8.0) of untreated [RA(−)] wild-type embryos, whereas they were expressed in the entire epiblast of RA-treated wild-type embryos at E6.25. In contrast, the expression of 501/301-Rm in wild-type embryos was not affected by RA treatment. (B) Expression of the 501/301 transgene in wild-type, Cyp26a1b1c1−/−, and Cyp26a1c1−/− embryos at E6.25 as revealed by X-gal staining. Lateral views are shown for each embryo with the anterior side on the left. The transgene was expressed in the posterior region of the wild-type embryo but was expressed in the entire epiblast of the mutant embryos.

The RARE of Nodal is highly conserved among mammals

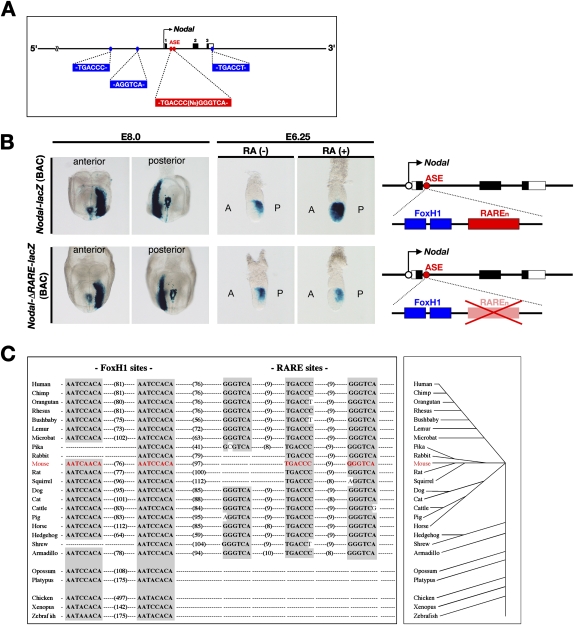

A search of the ∼70-kb genomic region encompassing mouse Nodal for the RARE-like sequence TGA(C/A)C(C/T)Nx(G/A)G(G/T)TCA (Ross et al. 2000) revealed RAREn to be the only copy, although half sites consisting of TGACCC, AGGTCA, or TGACCT were detected in the upstream region or 3′ untranslated region of the gene (Fig. 7A). To test whether RAREn in intron 1 is the only RA-responding element of Nodal, we generated a lacZ reporter construct [Nodal-lacZ (BAC)] from a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone containing an ∼200-kb genomic region including Nodal. The expression pattern of the Nodal-lacZ (BAC) construct in transgenic embryos mimicked that of endogenous Nodal (Fig. 7B; data not shown), and the transgene responded to administration of exogenous RA at E6.0 (Fig. 7B). However, a corresponding reporter construct [Nodal-ΔRARE-lacZ (BAC)] with a 25-bp deletion including RAREn failed to respond to exogenous RA (Fig. 7B), indicating that RAREn in intron 1 is the only functional RARE of mouse Nodal.

Figure 7.

Role of RAREn in regulation of Nodal expression in the epiblast and its structural conservation among mammals. (A) Relative positions of RAREn (red) and three RARE-like half sites (blue) in mouse Nodal. (B) X-gal staining of E8.0 and E6.25 embryos harboring the indicated lacZ (BAC) constructs. The expression pattern of Nodal-lacZ (BAC) mimicked that of endogenous Nodal and responded to the administration of exogenous RA at E6.0. Expression of Nodal-ΔRARE-lacZ (BAC) failed to respond to exogenous RA. (C, left panel) Evolutionary conservation of RARE-like and FoxH1-binding sequences in intron 1 of vertebrate Nodal genes; numbers in parentheses indicate nucleotide spacing. The vertebrate evolutionary tree is shown in the right panel.

Finally, we searched Nodal genes from 25 different vertebrates for RARE-like sequences as well as for the ASE and FoxH1-binding sequences (Fig. 7C). FoxH1-binding sequences act as an autoregulatory element that is required to amplify Nodal expression (Saijoh et al. 2000; Brennan et al. 2001). The ASE was found in intron 1 of all vertebrate Nodal genes examined. Two copies of the FoxH1-binding sequence, AAT(C/A)(C/A)ACA, were also detected in most of the vertebrate genes, whereas only one copy was found in the Nodal genes of pika, rabbit, and shrew. As suggested by mutational analysis of mouse Nodal ASE (Saijoh et al. 2000), a single FoxH1-binding site may be sufficient for autoregulation of the Nodal gene. A RARE-like sequence was found in the corresponding region (∼100 bp downstream from the FoxH1-binding sequences) of Nodal genes from all the mammals examined with the exception of opossum and platypus. Whereas rat, rabbit, and squirrel, like mouse, possess two half sites separated by 8 or 9 bp, the remaining mammalian species have three half sites each separated by 8, 9, or 10 bp. A RARE-like sequence was not detected in the corresponding region of Nodal or Nodal-related genes from nonmammalian vertebrates such as chicken, Xenopus, and zebrafish. RAREn is thus an RA-responsive transcriptional cis-element that is highly conserved among mammals, while FoxH1-binding sites are conserved among vertebrates.

Discussion

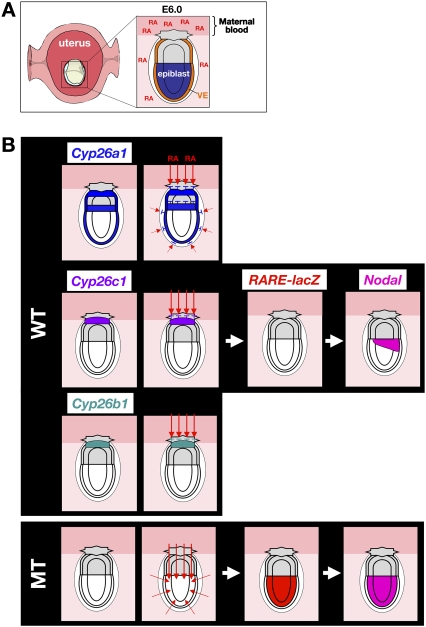

RA in the pregastrulation mouse embryo is likely of maternal origin, given that RALDH genes are not expressed within the embryo at this stage (Supplemental Fig. S1; Duester 2008; Niederreither and Dolle 2008). Raldh2 is highly expressed in the deciduas (Vermot et al. 2000), and RA is present in mouse serum at a concentration of ∼5 nM (Fig. 8A; Kane et al. 2008a,b). However, expression of CYP26 genes in the extraembryonic regions of the embryo prevents the epiblast from being exposed to RA (Fig. 8B), with the result that Nodal expression in the epiblast is maintained without activation of RAREn. Indeed, RA signaling as visualized with the RARE-hsplacZ transgene was not detected in embryos at E5.5 to E6.5 (Fig. 8B; Supplemental Fig. S1I,L), even though the epiblast expresses genes for intracellular components (including RA receptors [RARs] and retinoid X receptors [RXRs]) necessary for RA signaling (Supplemental Fig. S8) and is competent to respond to the RA signal (Fig. 2M). In the absence of CYP26s, however, maternally derived RA is able to reach the embryo proper and induces Nodal expression in the entire epiblast via RAREn (Fig. 8B). CYP26s thus act in a non-cell-autonomous manner to maintain the epiblast free of RA.

Figure 8.

Model for the role of CYP26 genes in early embryonic patterning. (A) In the pregastrulation mouse embryo, RA appears to be of maternal origin. Raldh2 is expressed in the decidua and RA is present in serum. (VE) Visceral endoderm. (B) The expression domains of the three CYP26 genes in the wild-type embryo at E6.25 are shown in the top panels. (Bottom panels) In mutant (MT) embryos lacking all three CYP26 genes, maternally derived RA activates Nodal expression in the entire epiblast via RAREn. Red arrows indicate the route of maternally derived RA. The removal of maternal RA by embryonic CYP26 is thus required for correct Nodal expression during embryonic patterning. See the text for details.

We found that the level of vitamin A in the diet influences the phenotype of Cyp26a1c1−/− and Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos (Supplemental Table S1). The conventional diet on which pregnant mice were maintained for the present experiments contains 3222 IU of vitamin A per 100 g of chow. An increase in the amount of vitamin A in chow to 4250 or 6000 IU/100 g resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in the frequency of the severe phenotype for both Cyp26a1c1−/− and Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos, consistent with the notion that the phenotypic variation among Cyp26a1c1−/− and Cyp26a1b1c1−/− embryos reflects a variable level of maternal RA. We also examined how much RA would be sufficient to induce early patterning defects in wild-type embryos by administering various doses of exogenous RA to pregnant wild-type mice at E5.5. The defects were not induced by oral administration of RA at 10, 20, or 40 mg per kilogram of body weight but were apparent in 57% (eight out of 14) of embryos exposed to RA at a dose of 50 mg/kg (Supplemental Fig. S9). Given that a dose of 50 mg/kg represents an amount of RA much higher than that contained in a conventional diet, the embryo is effectively protected by CYP26s under normal conditions. However, the administration of RA-containing drugs (such as tretinoin and isotretinoin for acne) or agents that inhibit the activity or expression of CYP26s (such as triazole antifungal agents) (Pautus et al. 2006) during early pregnancy might increase the risk of embryonic patterning defects.

With regard to the physiological role of RAREn, a transcriptional regulatory element of Nodal that is highly conserved among mammals, we found that the Nodal-lacZ-ΔRARE (BAC) transgene, which lacks RAREn, was expressed in mouse embryos in a manner similar to that of endogenous Nodal at least at E6.25 and E8.0. Consistent with this, loss of RA synthesis in the Raldh2 mutant mouse does not affect early Nodal expression (Niederreither et al. 2001). Although it may thus appear that the presence of RAREn only increases the risk of embryonic patterning defects, Nodal plays essential roles in other events, such as left–right patterning, at later stages of development. Given the highly conserved nature of RAREn, RAREn-mediated regulation of Nodal may play a key role in such events. Although the expression and function of Nodal have been studied extensively during early embryogenesis, they have not been examined in detail at later developmental stages or in the adult. It will be important to search for RAREn-dependent expression domains of Nodal at later developmental stages and to study their role in development and physiology.

Materials and methods

Generation of Cyp26a1b1c1−/− mice

Cyp26a1b1c1−/− mice were obtained by intercrossing Cyp26a1b1c1+/− mice, which were generated by mating Cyp26a1c1+/− mice (Uehara et al. 2007) with Cyp26b1+/− mice (Yashiro et al. 2004). All mice were maintained on a conventional diet (NMF; Oriental Yeast Co.) containing 3222 IU of vitamin A per 100 g of chow, unless indicated otherwise. Where indicated, mice were fed a special diet containing higher concentrations (4250 or 6000 IU/100 g) of vitamin A (CRF and NMF2, respectively; Oriental Yeast Co.).

RA treatment

RA treatment was performed as described previously (Yashiro et al. 2004) with minor modifications. Pregnant ICR mice at E6.0 or the indicated embryonic stages were thus administered all-trans RA (10 mg per kilogram of body weight unless indicated otherwise; Sigma) in sesame oil (Sigma) by oral gavage. Control females received sesame oil only.

Histological analysis

Mouse embryos were staged on the basis of their morphology. In situ hybridization was performed with whole-mount preparations as described previously (Sakai et al. 2001). To detect the RA signal in embryos, we crossed Cyp26a1b1c1+/− mice harboring the RARE-hsplacZ transgene (Rossant et al. 1991) with Cyp26a1b1c1+/− mice and subjected the resulting embryos to genotyping and staining with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal).

Transgenic reporter assay

Permanent transgenic lines harboring the 3′-1 or 501-301 lacZ transgenes have been described previously (Adachi et al. 1999). The Nodal-lacZ (BAC) transgene consists of the Nodal BAC clone RP23-55A6, with exon 1 of Nodal replaced by lacZ. The recombinant BAC clone was constructed with the use of the highly efficient recombination system in Escherichia coli (Copeland et al. 2001). To generate the Nodal-ΔRARE-lacZ (BAC) transgene, we replaced a 25-bp region including the TGACCCN9GGGTCA sequence with the FRT sequence. BAC DNA was prepared for microinjection (Gong et al. 2003), and transgenic mice were generated (Saijoh et al. 1999) as described previously.

Luciferase assay

The reporter assay was performed as described previously (Loudig et al. 2005). P19 (mouse teratocarcinoma) cells were cultured under 5% CO2 at 37°C in minimal essential medium (pH 7.2). The cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates 12 h before transfection with a total of 0.5 μg of DNA with the use of the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). After transfection for 24 h, the cells were exposed to all-trans RA in dimethyl sulfoxide for 24 h in the dark. The cells were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 100 μL of Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) for 15 min, after which the cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity with a Luciferase Assay System (Promega). All experiments were repeated three times.

Genome information from various vertebrates

The nucleotide sequence of intron 1 of Nodal was recovered for various vertebrates from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes) and was searched for the FoxH1-binding sequence AAT(C/A)(C/A)ACA and the RARE-like sequences TGACCC and GGGTCA.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Rossant for RARE-hsplacZ mice; E.J. Robertson for Nodal+/lacZ mouse; S. Aizawa, P. Koopman, and I. Matsuo for sharing reagents; as well as S. Ohishi, K. Yamashita, Y. Ikawa, K. Mochida, H. Nishimura, and A. Fukumoto for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and by CREST.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1776209.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Abu-Abed S, Dolle P, Metzger D, Beckett B, Chambon P, Petkovich M. The retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1, is essential for normal hindbrain patterning, vertebral identity, and development of posterior structures. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:226–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.855001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Abed S, MacLean G, Fraulob V, Chambon P, Petkovich M, Dolle P. Differential expression of the retinoic acid-metabolizing enzymes CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 during murine organogenesis. Mech Dev. 2002;110:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi H, Saijoh Y, Mochida K, Ohishi S, Hashiguchi H, Hirao A, Hamada H. Determination of left/right asymmetric expression of nodal by a left side-specific enhancer with sequence similarity to a lefty-2 enhancer. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1589–1600. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J, Lu CC, Norris DP, Rodriguez TA, Beddington RS, Robertson EJ. Nodal signalling in the epiblast patterns the early mouse embryo. Nature. 2001;411:965–969. doi: 10.1038/35082103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon J, Varlet I, Robertson EJ. Relationship between asymmetric nodal expression and the direction of embryonic turning. Nature. 1996;381:155–158. doi: 10.1038/381155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Court DL. Recombineering: A powerful new tool for mouse functional genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:769–779. doi: 10.1038/35093556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, Losos K, Didkovsky N, Schambra UB, Nowak NJ, Joyner A, Leblanc G, Hatten ME, et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MA, Folias AE, Napoli JL. HPLC/UV quantitation of retinal, retinol, and retinyl esters in serum and tissues. Anal Biochem. 2008a;378:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MA, Folias AE, Wang C, Napoli JL. Quantitative profiling of endogenous retinoic acid in vivo and in vitro by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008b;80:1702–1708. doi: 10.1021/ac702030f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudig O, Maclean GA, Dore NL, Luu L, Petkovich M. Transcriptional co-operativity between distant retinoic acid response elements in regulation of Cyp26A1 inducibility. Biochem J. 2005;392:241–248. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean G, Abu-Abed S, Dolle P, Tahayato A, Chambon P, Petkovich M. Cloning of a novel retinoic-acid metabolizing cytochrome P450, Cyp26B1, and comparative expression analysis with Cyp26A1 during early murine development. Mech Dev. 2001;107:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Russell DW. Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet. 2002;360:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K, Dolle P. Retinoic acid in development: Towards an integrated view. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:541–553. doi: 10.1038/nrg2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K, Vermot J, Messaddeq N, Schuhbaur B, Chambon P, Dolle P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for heart morphogenesis in the mouse. Development. 2001;128:1019–1031. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DP, Robertson EJ. Asymmetric and node-specific nodal expression patterns are controlled by two distinct cis-acting regulatory elements. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1575–1588. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautus S, Yee SW, Jayne M, Coogan MP, Simons C. Synthesis and CYP26A1 inhibitory activity of 1-[benzofuran-2-yl-(4-alkyl/aryl-phenyl)-methyl]-1H-triazoles. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:3643–3653. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Gomez A, Vella FD, Shawlot W, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Chazaud C, Meno C, Pfister V, Chen L, Robertson E, Hamada H, et al. Nodal antagonists in the anterior visceral endoderm prevent the formation of multiple primitive streaks. Dev Cell. 2002;3:745–756. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribes V, Fraulob V, Petkovich M, Dolle P. The oxidizing enzyme CYP26a1 tightly regulates the availability of retinoic acid in the gastrulating mouse embryo to ensure proper head development and vasculogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:644–653. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SA, McCaffery PJ, Drager UC, De Luca LM. Retinoids in embryonal development. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1021–1054. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossant J, Zirngibl R, Cado D, Shago M, Giguere V. Expression of a retinoic acid response element-hsplacZ transgene defines specific domains of transcriptional activity during mouse embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:1333–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijoh Y, Adachi H, Mochida K, Ohishi S, Hirao A, Hamada H. Distinct transcriptional regulatory mechanisms underlie left–right asymmetric expression of lefty-1 and lefty-2. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:259–269. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijoh Y, Adachi H, Sakuma R, Yeo CY, Yashiro K, Watanabe M, Hashiguchi H, Mochida K, Ohishi S, Kawabata M, et al. Left–right asymmetric expression of lefty2 and nodal is induced by a signaling pathway that includes the transcription factor FAST2. Mol Cell. 2000;5:35–47. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijoh Y, Oki S, Ohishi S, Hamada H. Left–right patterning of the mouse lateral plate requires nodal produced in the node. Dev Biol. 2003;256:160–172. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Meno C, Fujii H, Nishino J, Shiratori H, Saijoh Y, Rossant J, Hamada H. The retinoic acid-inactivating enzyme CYP26 is essential for establishing an uneven distribution of retinoic acid along the anterio–posterior axis within the mouse embryo. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:213–225. doi: 10.1101/gad.851501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirbu IO, Gresh L, Barra J, Duester G. Shifting boundaries of retinoic acid activity control hindbrain segmental gene expression. Development. 2005;132:2611–2622. doi: 10.1242/dev.01845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahayato A, Dolle P, Petkovich M. Cyp26C1 encodes a novel retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme expressed in the hindbrain, inner ear, first branchial arch and tooth buds during murine development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:449–454. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara M, Yashiro K, Mamiya S, Nishino J, Chambon P, Dolle P, Sakai Y. CYP26A1 and CYP26C1 cooperatively regulate anterior–posterior patterning of the developing brain and the production of migratory cranial neural crest cells in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2007;302:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umesono K, Murakami KK, Thompson CC, Evans RM. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell. 1991;65:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermot J, Fraulob V, Dolle P, Niederreither K. Expression of enzymes synthesizing (aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 and reinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2) and metabolizaing (Cyp26) retinoic acid in the mouse female reproductive system. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3638–3645. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Saijoh Y, Perea-Gomez A, Shawlot W, Behringer RR, Ang SL, Hamada H, Meno C. Nodal antagonists regulate formation of the anteroposterior axis of the mouse embryo. Nature. 2004;428:387–392. doi: 10.1038/nature02418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K, Zhao X, Uehara M, Yamashita K, Nishijima M, Nishino J, Saijoh Y, Sakai Y, Hamada H. Regulation of retinoic acid distribution is required for proximodistal patterning and outgrowth of the developing mouse limb. Dev Cell. 2004;6:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]