Abstract

ThiI catalyzes the thio-introduction reaction to tRNA, and a truncated tRNA consisting of 39 nucleotides, TPHE39A, is the minimal RNA substrate for modification by ThiI from Escherichia coli. To examine the molecular basis of the tRNA recognition by ThiI, we have solved the crystal structure of TPHE39A, which showed that base pairs in the T-stem were almost completely disrupted, although those in the acceptor-stem were preserved. Gel shift assays and isothermal titration calorimetry experiments showed that ThiI can efficiently bind with not only tRNAPhe but also TPHE39A. Binding assays using truncated ThiI, i.e., N- and C-terminal domains of ThiI, showed that the N-domain can bind with both tRNAPhe and TPHE39A, whereas the C-domain cannot. These results indicated that the N-domain of ThiI recognizes the acceptor-stem region. Thermodynamic analysis indicated that the C-domain also affects RNA binding by its enthalpically favorable, but entropically unfavorable, contribution. In addition, circular dichroism spectra showed that the C-domain induced a conformation change in tRNAPhe. Based on these results, a possible RNA binding mechanism of ThiI in which the N-terminal domain recognizes the acceptor-stem region and the C-terminal region causes a conformational change of RNA is proposed.

Keywords: ThiI, binding, recognition, tRNA modification, thio introduction

INTRODUCTION

Post-transcriptional modification produces a diverse array of RNA molecules, and plays various cellular roles from stabilization of the structured RNA, fidelity control of translation, to metabolic response to the environment (Persson 1993; Curran 1998). More than 100 chemically modified nucleosides have been reported to date, and the largest numbers are found in tRNAs (Rozenski et al. 1999). In bacterial and archaeal tRNA, 4-thiouridyl modification (s4U) is found at position 8, which characteristically acts as a photosensor for near-UV (Favre et al. 1969; Favre et al. 1971; Bergstrom and Leonard 1972). By irradiation with near-UV light, s4U is photocross-linked with a cytidine at position 13 in the tRNA D-stem (Favre et al. 1971). This results in growth delay and a stringent response to amino acid starvation, as cross-linked tRNAs are poor substrates for aminoacylation (Thomas and Favre 1975; Kramer et al. 1988).

s4U modification is introduced at position 8 by the cooperative activity of two enzymes, ThiI and IscS, transferring a sulfur atom from cysteine to tRNA (Supplemental Fig. S1; Kambampati and Lauhon 2000). First, IscS removes a sulfur atom from cysteine, which results in the formation of alanine and IscS-bound persulfide (IscS-SSH). This persulfide sulfur of IscS is then transferred to a cysteine residue on ThiI, resulting in ThiI persulfide (ThiI-SSH). Finally, in the presence of ATP, the persulfide sulfur from ThiI-SSH is transferred to tRNA.

ThiI from γ-proteobacteria and archaea consists of four domains, i.e., an N-terminal ferredoxin-like domain (NFLD), thio uridine synthases RNA methyltransferases and pseudo-uridine synthases (THUMP), modified P-loop motif involved in pyrophosphate binding (PP-loop domain), and rhodanese-like domain (RLD) (Webb et al. 1997; Palenchar et al. 2000; Waterman et al. 2006). As the THUMP domain is common to several RNA binding proteins, it likely acts as an RNA recognition motif (Aravind and Koonin 2001; Gabant et al. 2006). The crystal structures of ThiI from Pyrococcus horikoshii and Bacillus anthracis, which did not contain RLD, revealed an elongated structure in which the THUMP domain and the PP-loop domain were separated, with NFLD located between them (Waterman et al. 2006). As AMP was found in the PP-loop domain of B. anthracis ThiI, the PP-loop domain was thought to be an active domain. The sulfur atom is transferred from ThiI to tRNA via a cysteine residue. Escherichia coli ThiI contains five cysteine residues, Cys108, Cys202, Cys207, C344, and Cys456. Among these, previous mutational analysis showed that Cys344 and Cys456 are important for the activity (Palenchar et al. 2000; Mueller et al. 2001).

Lauhon et al. (2004) examined the substrate specificity for s4U modification by deletion analysis of tRNAPhe, and showed that TPHE39A, consisting of 39 nucleotides (nt) including the acceptor-stem, a bulged loop, the T-stem, and the modified T-loop, was the minimal efficient substrate with activity nearly two-thirds that of full-length tRNAPhe, i.e., initial rate constant (kobs) and dissociation constant (Kd) of tRNAPhe and TPHE39A were 1.01 ± 0.13 min−1 and 1.9 ± 0.17 μM and 0.61 ± 0.06 min−1 and 8.2 ± 1.7 μM, respectively. It was also reported that: (1) the bulged loop must be at least 4 nt in length, and contain the target uridine as the first nucleotide; (2) the primary sequence in the T-loop is not a recognition element; and (3) a 3′-CCA overhang is required for activity. These discussions were based on the assumption that tertiary structures should be retained even in truncated RNA molecules, although no evidence for this was obtained.

In the present study, we investigated the RNA recognition mechanism using tRNAPhe and TPHE39A as RNA molecules, and ThiI from E. coli, N- and C-terminal domains of ThiI as proteins. Based on the results of X-ray crystallography, gel shift assay, isothermal titration calorimetry, and CD spectrometry, we propose a mechanism for the binding of ThiI with tRNA.

RESULTS

Crystal structure of TPHE39A

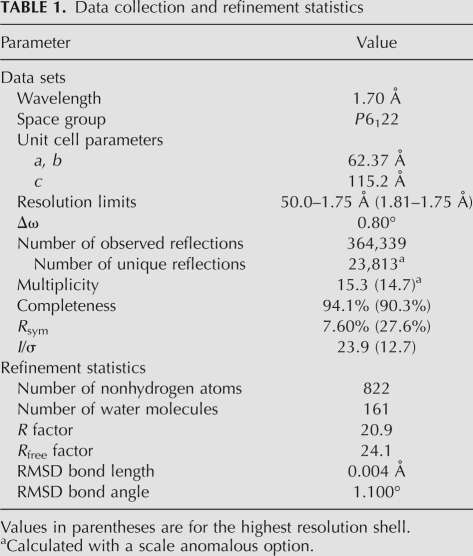

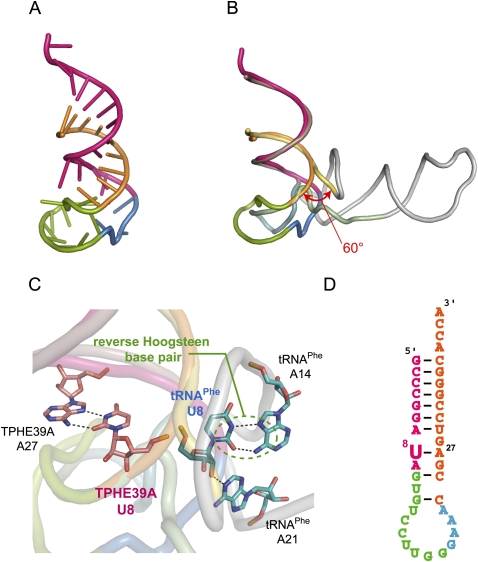

Previously, TPHE39A (Fig. 1) was shown to be the minimal RNA fragment that can be modified by ThiI, although its activity was decreased by about 40% compared with that of intact tRNAPhe. TPHE39A consists of the acceptor-stem and the T-arm with the T-loop substituted by the artificial GAAA sequence, which are connected together with a 7-nt loop. In this study, the crystal structure of TPHE39A was determined at a resolution of 1.75 Å by the SAD method using calcium ions and phosphate atoms as anomalous scatterers (diffraction data statistics are described in Table 1). The asymmetric unit contains one molecule of TPHE39A, one magnesium ion, one chloride ion, seven calcium ions, and 161 water molecules. Based on the intact tRNAPhe structure, it has been suggested that TPHE39A should have a conserved secondary structure as shown in Figure 1B. In contrast to this expectation, TPHE39A revealed substantial alterations in the secondary structure of the T-stem. Figure 2B shows the superposition between TPHE39A and the full-length tRNA, in which all atoms in G1–A9 were superposed. In tRNAPhe, the target uridine of ThiI, U8, forms a reverse Hoogsteen base pair with A14 and a hydrogen bond with A21 (Dirheimer et al. 1995). However, in TPHE39A, U8 flipped into the T-stem region and formed a base pair with A27, instead of U16, in the T-stem (Fig. 2C,D). This conformational change may be due to the absence of A14 and A21 in TPHE39A. As consequences of this unnatural U8–A27 base pair, other Watson–Crick base pairings in the T-stem region were mostly disrupted (Fig. 2D). G10–G19 in the T-stem of TPHE39A (corresponding to G44–G53 in tRNAPhe) together with the T-loop formed a large bulged loop structure, whereas this region forms the T-stem in tRNAPhe. By connecting to this large loop region, the 3′-end of the 5′ acceptor-stem region, i.e., the region of A7–A9, was distorted by about 60° to the direction of the T-stem region (Fig. 2B). Most of magnesium and calcium ions were located around this bulged loop. Moreover, C14 and C15 formed base pairs with G18 and G20 in the bulged loop of an adjacent RNA molecule in the crystal. These resulted in the stabilization of a loop conformation, and reduced the crystallographic B factors compared to those of the acceptor stem. The contact interface between two TPHE39A molecules was calculated to be 777.7 Å2, which is ∼10% of the whole surface area (7359 Å2). A native gel, as well as a gel filtration analyses, indicated the monomeric behavior of TPHE39A in the solution (data not shown). Since nucleotides in the bulged loop did not form intramolecular base pairs, it is possible that this loop has certain flexibility in solution. Several nucleotides exposed into solvent, i.e., C14, C15, G18, and G20, would be incidentally stabilized by base pairings in crystals.

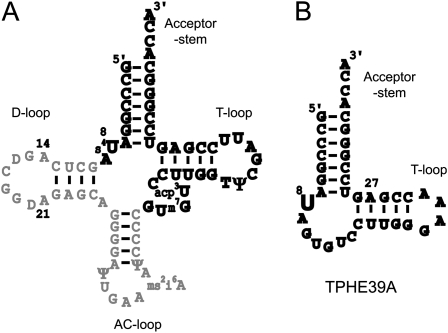

FIGURE 1.

(A) Secondary structure representation of tRNAPhe and (B) predicted structure of TPHE39A. Nucleotides included in TPHE39A are shown in bold in A.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of TPHE39A. (A) Overall structure of TPHE39A. The acceptor-stem regions are colored orange (G1–A9) and pink (C24–C38). Nucleotides corresponding to the T-stem and the T-loop in tRNAPhe are shown in green (G10–G19) and blue (G20–A23), respectively. (B) Superposition of TPHE39A and tRNAPhe. Atoms of G1–A9 are used for superposition. Nucleotides corresponding to the acceptor-stem (G1–A9), acceptor-stem (U66–A76), T-stem, T-loop, and others are colored pastel yellow, pastel pink, pastel green, pastel blue, and gray, respectively. (C) Close-up view around U8. U8 and its base-pairing nucleotides in TPHE39A and tRNAPhe are shown as pink and blue sticks, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are also shown as dotted lines. Colors of other regions correspond to those in B. (D) Secondary structure of TPHE39A according to the crystal structure.

Despite differences in the T-stem region, TPHE39A and tRNAPhe had quite similar structures in the acceptor-stem with a RSMD of 2.79 Å for the 297 atoms that were compared. In conclusion, TPHE39A possessed a rod-like structure with canonical base pairings in the acceptor-stem and distorted conformation of the T-stem including the U8–A27 base pair.

Binding assay with truncated ThiI and tRNA

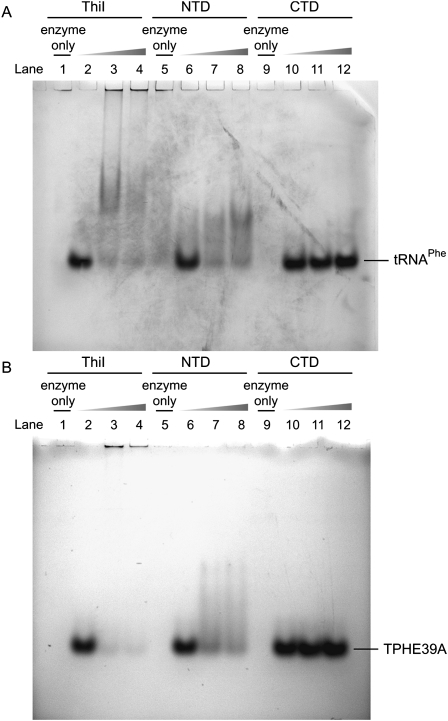

To explore the RNA recognition mechanism of ThiI, we prepared two truncated forms of ThiI containing the N-terminal domain (NTD) including NFLD and THUMP, and the C-terminal domain (CTD) including the PP-loop and RLD, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2), and subsequently verified their RNA binding ability by gel shift assay and the ITC method. Prior to the assays, their structural integrities were confirmed by CD spectra compared to that of the full-length protein (data not shown). Figure 3 shows the results of gel shift assays. In the cases of both intact ThiI and NTD, free RNA bands disappeared with the increase in protein concentration, suggesting that these proteins are capable of binding to tRNAPhe (Fig. 3A). In contrast, adding CTD did not affect the amount of tRNAPhe (Fig. 3A). Similar observations were also made in the case of TPHE39A (Fig. 3B). These results strongly suggest that NTD alone held the potential for RNA-binding activity. At the same time, the results also suggested that TPHE39A could be precisely recognized by ThiI regardless of the drastic structural changes in the T-stem as described above.

FIGURE 3.

Results of the gel shift assay. Interaction between (A) tRNAPhe and (B) TPHE39A: (lanes 1,5,9) 100 pmol protein; (lanes 2,6,10) 100 pmol RNA; (lanes 3,7,11) 100 pmol protein + 100 pmol RNA; and (lanes 4,9,12) 200 pmol protein + 100 pmol RNA.

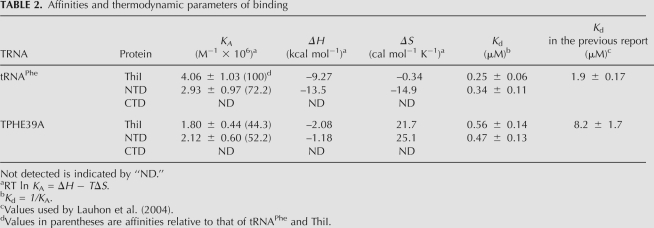

Next, we measured the affinity of each protein with RNAs by ITC (Table 2). The association constants of ThiI against tRNAPhe and TPHE39A were (4.02 ± 1.03) × 106 and (1.80 ± 0.44) × 106 M−1, respectively. While the value decreased to about 44% of the intact tRNA, TPHE39A possessed a certain binding capacity to ThiI. The affinity constants of NTD against tRNAPhe and TPHE39A were calculated to be (2.93 ± 0.97) × 106 and (2.12 ± 0.60) × 106 M−1, respectively, which were 72.2% and 52.2% those of ThiI, respectively. The dissociation constants of ThiI against tRNAPhe and TPHE39A calculated from association constants determined by ITC were 0.25 ± 0.06 and 0.56 ± 0.14 μM, respectively, which were markedly smaller than those previously reported using a filter binding assay (1.9 ± 0.17 and 8.2 ± 1.7 μM, respectively) (Table 2; Lauhon et al. 2004). This would be due to the difference of the methods used. These values accord with each other in that Kd between ThiI and tRNAPhe is smaller than that between ThiI and TPHE39A. On the other hand, neither tRNAPhe nor TPHE39A bound to CTD in ITC experiments, consistent with the results of the gel shift assay (Fig. 3). Taken together, the substrate selectivity between ThiI and tRNA is likely governed by the specific interactions between the NTD and the acceptor-stem, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Affinities and thermodynamic parameters of binding

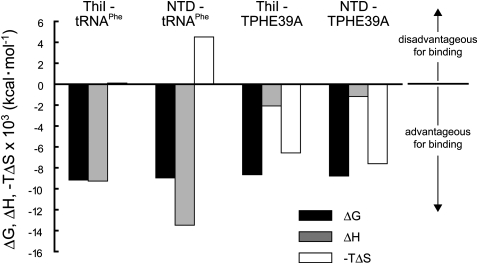

Whereas the RNA affinity was not markedly affected, the thermodynamic parameters were remarkably altered by truncation of tRNA (Table 2). The enthalpy contribution on binding (ΔH) decreased from –9.27 to –2.08 kcal mol−1 in the case of ThiI, and from –13.5 kcal mol−1 to –1.18 kcal mol−1 for NTD. On the other hand, the entropy contribution increased from –0.34 to 21.7 cal mol−1 K−1 for ThiI, and from –14.9 to 25.1 cal mol−1 K−1 for NTD. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of each interaction. These experimental values imply that interactions with tRNAPhe are enthalpy-driven in both cases of ThiI and NTD, whereas those with TPHE39A are mainly entropy-driven. In addition, deletion of the C-terminal domain of ThiI also caused significant changes in enthalpy and entropy contributions. Focusing on binding with tRNAPhe, the enthalpic contribution increased but that of entropy decreased. However, no such marked changes were observed in binding with TPHE39A.

FIGURE 4.

Breakdowns of thermodynamic parameters in each interaction pair. Gibbs energy, enthalpy change, and entropy change are shown as black, gray, and white bars, respectively.

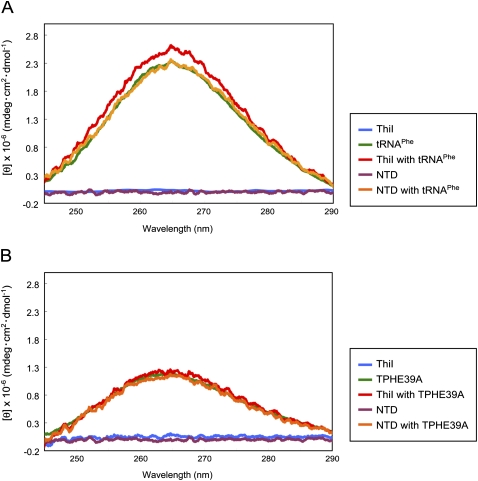

Circular dichroism spectra of tRNAPhe and TPHE39A in the presence or absence of proteins

To confirm that structural changes of RNAs accompany ThiI binding, we measured circular dichroism (CD) spectra of RNAs in the presence or absence of ThiI and NTD. Figure 5A shows the results for tRNAPhe. Without ThiI, tRNAPhe gave positive CD between 245 and 290 nm with a peak around 265 nm, which was not observed for the proteins. Therefore, this peak likely reflected the conformation of tRNAPhe. Interestingly, the CD intensity of this region increased slightly, but significantly when ThiI was added to tRNAPhe, suggesting that ThiI induced a structural change in tRNAPhe. In contrast, no spectral changes were detected when NTD was added, indicating that the N-terminal domain itself did not induce a conformation change of tRNAPhe, although it can bind with tRNAPhe. Taken together, it is possible that the C-terminal domain of ThiI has some important roles in the structural change of bound substrate tRNAPhe.

FIGURE 5.

CD spectra of (A) tRNAPhe and (B) TPHE39. Spectra of RNA, RNA with ThiI, and RNA with NTD are shown as green, red, and orange lines, respectively, and those of ThiI and NTD are shown in blue and purple, respectively.

Similar experiments were also performed for TPHE39A (Fig. 5B). In analogy with tRNAPhe, TPHE39A also showed positive CD between 245 and 290 nm with a peak around 265 nm, although the intensity was weaker than that of tRNAPhe. It should be noted that no spectral changes were observed with addition of proteins, although intact ThiI was used, suggesting that the structure of TPHE39A was unaffected by protein binding. Taken together, these results lead to the conclusion that the structural change induced by the C-terminal domain should occur in regions that exist in tRNAPhe, but not in TPHE39A, or in those where the structure has deviated between tRNAPhe and TPHE39A.

DISCUSSION

Deduced RNA recognition mechanism of ThiI

Despite a significant conformational change of the T-stem region, ThiI could bind to TPHE39A without a significant decrease in the affinity (Table 2). CD spectra showed that no significant structural change occurred in TPHE39A on binding with ThiI, which allowed us to discuss the binding mechanism between ThiI and TPHE39A based on the determined structure of TPHE39A. Taken together, these results indicate that the acceptor-stem region plays an important role in binding with ThiI, which is in good agreement with a previous report by Lauhon et al. (2004), indicating that deleting nucleotides in the acceptor-stem and/or 3′-terminal nucleotides markedly impaired modification activity. On the other hand, Lauhon et al. (2004) also reported that replacing sequences of the T-loop by a GAAA sequence in truncated tRNA significantly increased the activity. In TPHE39A, the T-stem was disrupted and formed a large bulged loop together with the T-loop sequences (Fig. 2). It is possible that the sequences of this region in TPHE39A can incidentally possess a conformation that does not disturb binding with ThiI. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that the T-loop in truncated tRNA must contain at least 4 nt to be efficiently modified by ThiI (Lauhon et al. 2004). The length of this region would significantly affect the conformation of the large loop, and thus the activity.

Binding assays with domain-truncated ThiIs showed that NTD contributes strongly to the RNA binding. To date, there have been no reports confirming the interaction between the THUMP domain and RNA, although it is found in several RNA modification enzymes and is therefore likely to serve as a general module for interaction with RNA (Aravind and Koonin 2001; Gabant et al. 2006). The present study is the first to confirm this. Considering the structural identity in the acceptor-stem between tRNAPhe and TPHE39A, it is possible that NTD binds RNA by recognizing the acceptor-stem. The interaction between a minimal molecule pair, i.e., TPHE39A and NTD, was calculated as entropy-driven (Fig. 4; Table 2). Many nucleic acid–protein interactions are assigned as entropy-driven, to which dehydration of nucleic acids makes a contribution (Jen-Jacobson et al. 2000; Privalov et al. 2007). The interaction between NTD and the acceptor-stem may also involve a dehydration effect. However, the breakdown of enthalpy and entropy contributions changed markedly upon truncation of tRNA (Fig. 4), i.e., the enthalpy driven interaction for tRNAPhe changed to an entropy-driven interaction in TPHE39A, suggesting that some regions other than the acceptor-stem also participate in binding. These regions may have enthalpic advantages but entropic disadvantages. It is remarkable that the interaction between NTD and tRNAPhe is enthalpically advantageous and entropically disadvantageous as compared with ThiI and tRNAPhe (Fig. 4). These changes must be derived from CTD. As the binding affinity did not decrease markedly and CTD could bind neither tRNAPhe nor TPHE39A, these enthalpic and entropic effects by CTD would be offset by each other almost completely.

Taken together, we concluded that: (1) NTD is necessary for ThiI–tRNA binding, (2) NTD recognizes the acceptor-stem; (3) a region(s) other than the acceptor-stem is also recognized by NTD; and (4) CTD can also affect the interaction by favorable enthalpy and unfavorable entropy, but they are canceled out by each other.

Structural changes in RNA over binding with ThiI

CD spectra showed that CTD induces a conformational change in some region other than the acceptor-stem in tRNA (Fig. 5A). Spectral changes in this region were reported to indicate conformational changes of nucleic acid molecules (Connor et al. 1994; Gray et al. 1995; Nejedly et al. 2005; Saito et al. 2008). Gabant et al. (2006) reported for ThiI and other tRNA modification enzymes that some conformational rearrangement, such as base flipping in the substrate tRNA, must occur to expose the target nucleoside and place it in the active site. The crystal structure of ThiI from B. anthracis showed that CTD contains the catalytic core (Waterman et al. 2006). The conformational change detected on CD spectra may correspond to these rearrangements, i.e., base flipping of U8. In several DNA or RNA modification enzymes, base flipping upon enzyme–DNA or enzyme–RNA interaction was observed (Roberts and Cheng 1998; Ishitani et al. 2008). It is also likely that larger conformational change such as the λ-form tRNA can occur upon ThiI binding (Ishitani et al. 2008). In either case, we cannot conclude this exactly at the present stage. CTD is necessary for the structural change; however, this domain requires NTD for binding to tRNA. As described above, CTD has some favorable enthalpic and unfavorable entropic effects for tRNA binding. These effects may contribute to the structural changes of tRNA. As the modification activity of TPHE39A by ThiI is almost two-thirds that of tRNAPhe, this significant decrease in modification efficiency may be due to the loss of conformational change by CTD.

Conclusions

In this study, we examined the interaction between ThiI and tRNA on the basis of the crystal structure of TPHE39A, binding assays, and CD spectra. We demonstrated an RNA binding mechanism of ThiI in which NTD binds to the acceptor-stem region of tRNA, and CTD causes some conformational changes of tRNA. Our results showed that truncation of RNA causes some unexpected structural changes, and therefore RNA molecules should be designed carefully when using truncated molecules. A high-resolution structure of ThiI in complex with tRNA is essential to determine the precise binding and/or modification mechanism of ThiI. We now are attempting to prepare co-crystals of ThiI and RNA molecules. The present study provided some critical clues to understand the precise modification mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of expression vector for ThiI and truncated proteins

The gene encoding ThiI was amplified using KOD-Plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo), with E. coli genomic DNA as the template and the following primers:

ThiI-S (5′-AGCTATCCATATGAAGTTTATCATTAAATTGTTC-3′); and

ThiI-AS (5′-ATCAGATCTTACGGGCGATATACCTTCACAT-3′).

Restriction enzyme sites for digestion and ligation are underlined. The PCR products were inserted into the NdeI and BglII sites of the pET-Duet vector (Merck). To achieve a uniform reductive state of active cysteine residues in ThiI, i.e., C344 and C456, IscS, the sulfur atom donor for ThiI, was co-expressed with the pET-Duet vector. ThiI was expressed without any tags, but a hexahistidine tag was attached at the N-terminus of IscS for ease of isolation from ThiI on Ni-affinity resin.

According to the crystal structure of ThiI from Bacillus anthracis, the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal domain of E. coli ThiI were defined as follows: NTD, Met1-Gln177; and CTD, Glu178-Pro482. Each gene was amplified from the ThiI expression vector with the following primer sets:

For NTD:

ThiI-N-domain-S (5′-GGAATTCCATATGAAGTTTATCATTAAATTGTTCCCG-3′), and

ThiI-N-domain-AS (5′-ACGCGTCGACCTGGGTGCCGATCGGGAA-3′).

For CTD:

ThiI-C-domain-S (5′-GGAATTCCATATGGAAGATGTGCTGTCGCTCATTTCC-3′), and

ThiI-C-domain-AS (5′-ACGCGTCGACCGGGCGATATACCTTCACATTG-3′).

After digestion with NdeI and XhoI, each gene was introduced into the pET-28b vector. A His6 tag was fused at the C-termini of both fragments for the purpose of purification. The correctness of the DNA sequences was confirmed using an ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Expression and purification of ThiI and truncated ThiI

ThiI was expressed in E. coli strain B834(DE3) at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin. To induce ThiI expression, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at the early stationary phase of culture to a final concentration of 1 mM, and culture was continued for another 3 h. Truncated ThiIs were expressed in E. coli strain B834(DE3) harboring pT-RIL (Stratagene) in LB medium containing 25 μg mL−1 kanamycin and 34 μg mL−1 chloramphenicol. The expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG at the early stationary phase of culture and processed for 18 h at 25°C.

The procedure for purification of tag-free intact ThiI was as follows. Harvested cells were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and disrupted with a sonicator (Branson). The soluble fraction was loaded onto a HiTrap Chelating HP column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) to remove co-expressed IscS. The flow-through fractions containing soluble ThiI were collected, and further purified by HiTrap Heparin HP, Resource Q, and HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200-pg (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). After confirmation of the purity by SDS-PAGE, the purified proteins were used for further experiments.

NTD and CTD were purified on a HiTrap Chelating HP column with a linear gradient of 0–500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing the desired protein were further purified on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200-pg column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences).

Preparation of tRNAPhe and TPHE39A

RNAs were prepared as described previously by Nakamura et al. (2006). Double-stranded DNA transcription templates for in vitro transcription to produce RNA molecules were amplified with Taq DNA polymerase using three overlapping oligo-DNAs, respectively, as follows:

For tRNAPhe:

5′-primer: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGCCCGGATAGCTCAGTCGGTAG-3′;

Mid-primer: 5′-GGATAGCTCAGTCGGTAGAGCAGGGGATTGAAAATCCCCGTGTCCTTGGTTCGATTCCG -3′; and

3′-primer: 5′-TGmGTGCCCGGACTCGGAATCGAACCAAGGAC-3′.

For TPHE39A:

5′-primer: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGCCCG-3′;

Mid-primer: 5′-CTCACTATAGCCCGGATAGTGTCCTTGGGAAACCGAGTCCG-3′; and

3′-primer: 5′-TGmGTGCCCGGACTCGGTTTCCC-3′.

The amplified DNA fragments were purified on a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) equilibrated with water. The in vitro transcription was performed in a solution containing 40 mM HEPES–NaOH, pH 7.8, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermine, 5 mM DTT, 100 mM KCl, 0.05 mg/mL BSA, 0.01% Triton X-100, 1 mM NTPs, 5 mM GMP, 4 μg/mL transcription template, and 0.02 mg/mL T7 RNA polymerase at 37°C for 12 h. Transcribed tRNAPhe was subsequently precipitated in 50% isopropanol, and loaded onto a denaturing urea-polyacrylamide gel. RNAs of the correct size were extracted from the gel, and then refolded with 500 mM NH4 acetate (pH 6.0), 5 mM Mg acetate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS at 37°C for 6 h. Transcribed TPHE39A was further purified to homogeneity on a Resource Q and HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200-pg column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). Purified RNAs were precipitated with isopropanol, and then stored at –30°C until use.

Crystallization of TPHE39A

Initially, we attempted to prepare TPHE39A–ThiI complex crystals; however, only TPHE39A alone was crystallized. The purified TPHE39A pellet was dissolved with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 300 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol at a concentration of 12 mg mL−1, and then mixed with concentrated ThiI (10 mg mL−1) solution in the same buffer with a molar ratio of 1.5:1 for TPHE39A:ThiI. The protein–RNA mixture was used for crystallization after incubation at 4°C for 12 h. Crystals of TPHE39A were grown by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method from the well solution containing 0.2 M calcium acetate, 0.2 M sodium chloride, 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.0), and 40% (v/v) MPD.

X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction was performed on the beamline NW12 at PF-AR, Photon Factory under cryogenic conditions (100 K). For single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) phasing utilizing phosphate atoms in the backbone of RNA molecules, a wavelength of 1.70 Å was chosen. A diffraction data set was collected up to a resolution of 1.75 Å with a Quantum 210 detector (ADSC). The TPHE39A crystal belonged to the space group P6122 with unit cell parameters a = b = 62.37 Å and c = 115.2 Å. The diffraction data were indexed, integrated, scaled, and merged using the HKL2000 program package (Otwinowski and Minor 1997).

Structure solution and refinement

The initial phasing was achieved by SAD with the program SHELX (Sheldrick 2008). SHELXD identified 46 anomalous scatterer sites, including phosphate atoms and calcium ions using the substructure structure factors calculated by SHELXC. The initial electron density map was obtained after phase calculation and its improvement by density modification with the solvent contents of 0.45 using the program SHELXE. Twenty-seven of 39 nt were built automatically by the PHENIX package (Adams et al. 2002), and all bases except A39 were built manually using the graphical program Coot (Emsley and Cowtan 2004), based on the initial electron density map. Positional and individual B factor refinement of the TPHE39A model was carried out with the program REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al. 1997), using reflections ranging from 50 to 1.75 Å. A random 4.9% of all observed reflections were set aside for cross-validation analysis and used for monitoring throughout the refinement by calculating the free R value (Rfree). The final model consisted of 39 nt, one magnesium ion, one chloride ion, seven calcium ions, and 161 water molecules with crystallographic R and Rfree values of 20.9% and 24.1%, respectively. The crystallographic parameters and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Gel shift assay

Procedures to confirm interactions between protein and RNA molecules were, in principle, those followed by Nakamura et al. (2006). Gel shift assays were performed in 10-μL reaction mixtures containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 300 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and the desired amounts of tRNA and protein. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 15 min, and then immediately loaded onto a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel composed of 25 mM Tris-MES (pH 6.8), 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM magnesium acetate, and 20 mM ammonium acetate. Electrophoresis conditions were as follows: temperature, 4°C; power voltage, 60 V; and time, 4 h.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

All ITC measurements were carried out with a VP-ITC System (MicroCal). Proteins and RNAs were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.6) containing 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and then their concentrations were calculated from the absorptions at 280 and 260 nm, respectively. The cell was filled with ∼10 μM protein solution, and a syringe was filled with ∼100 μM RNA. The protein solution was injected 25 times in portions of 10 μL over 20 s. The data obtained were analyzed with the program ORIGIN (MicroCal). Thermograms and calculated thermodynamic parameters are shown in Supplemental Fig. S3 and Table 2. Breakdowns of Gibbs free energy, enthalpy, and entropy contributions are also shown in Figure 4.

Circular dichroism measurements

CD spectra were measured on a JASCO J-720 spectropolarimeter (JASCO) in a quartz cell with an optical path length of 2 mm. The CD spectra were obtained by taking the average of four scans made from 400 to 190 nm and normalized to molar ellipticities by protein or RNA concentrations determined from absorption at 280 and 260 nm, respectively.

Data deposition

The atomic coordinates for TPHE39A have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 2ZY6.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. N. Hirano of Hokkaido University for her technical assistance. We also thank Dr. K. Makabe of the National Institutes of Natural Sciences, Okazaki Institute for Integrative Bioscience, and Dr. K. Matsuo of Hiroshima University for their helpful suggestions, and Dr. S. Takeda for his help in ITC analysis. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Younger Scientists (Y.T. and S.C.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. It was supported in part by the Exchange Program for East Asian Young Researchers from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1614709.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Koonin EV. THUMP—a predicted RNA-binding domain shared by 4-thiouridine, pseudouridine synthases and RNA methylases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01826-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom DE, Leonard NJ. Photoreaction of 4-thiouracil with cytosine. Relation to photoreactions in Escherichia coli transfer ribonucleic acids. Biochemistry. 1972;11:1–9. doi: 10.1021/bi00751a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor F, Cary PD, Read CM, Preston NS, Driscoll PC, Denny P, Crane-Robinson C, Ashworth A. DNA binding and bending properties of the post-meiotically expressed Sry-related protein Sox-5. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3339–3346. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.16.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran JF. Modification and editing of RNA. American Society for Microbiology Press; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dirheimer G, Keith G, Dumas P, Westhof E. tRNA: Structure biosynthesis and function. American Society for Microbiology Press; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre A, Yaniv M, Michelson AM. The photochemistry of 4-thiouridine in Escherichia coli t-RNA Val1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969;37:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre A, Michelson AM, Yaniv M. Photochemistry of 4-thiouridine in Escherichia coli transfer RNA1Val. J Mol Biol. 1971;58:367–379. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabant G, Auxilien S, Tuszynska I, Locard M, Gajda MJ, Chaussinand G, Fernandez B, Dedieu A, Grosjean H, Golinelli-Pimpaneau B, et al. THUMP from archaeal tRNA:m22G10 methyltransferase, a genuine autonomously folding domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2483–2494. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DM, Hung SH, Johnson KH. Absorption and circular dichroism spectroscopy of nucleic acid duplexes and triplexes. Methods Enzymol. 1995;246:19–34. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)46005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani R, Yokoyama S, Nureki O. Structure, dynamics, and function of RNA modification enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen-Jacobson L, Engler LE, Jacobson LA. Structural and thermodynamic strategies for site-specific DNA binding proteins. Structure. 2000;8:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambampati R, Lauhon CT. Evidence for the transfer of sulfane sulfur from IscS to ThiI during the in vitro biosynthesis of 4-thiouridine in Escherichia coli tRNA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10727–10730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer GF, Baker JC, Ames BN. Near-UV stress in Salmonella typhimurium: 4-Thiouridine in tRNA, ppGpp, and ApppGpp as components of an adaptive response. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2344–2351. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2344-2351.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauhon CT, Erwin WM, Ton GN. Substrate specificity for 4-thiouridine modification in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23022–23029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller EG, Palenchar PM, Buck CJ. The role of the cysteine residues of ThiI in the generation of 4-thiouridine in tRNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33588–33595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Yao M, Chimnaronk S, Sakai N, Tanaka I. Ammonia channel couples glutaminase with transamidase reactions in GatCAB. Science. 2006;312:1954–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.1127156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejedly K, Chladkova J, Vorlickov M, Hrabcova I, Kypr J. Mapping the B-A conformational transition along plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palenchar PM, Buck CJ, Cheng H, Larson TJ, Mueller EG. Evidence that ThiI, an enzyme shared between thiamin and 4-thiouridine biosynthesis, may be a sulfurtransferase that proceeds through a persulfide intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8283–8286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson BC. Modification of tRNA as a regulatory device. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1011–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privalov PL, Dragan AI, Crane-Robinson C, Breslauer KJ, Remeta DP, Minetti CA. What drives proteins into the major or minor grooves of DNA? J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ, Cheng X. Base flipping. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:181–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenski J, Crain PF, McCloskey JA. The RNA Modification Database: 1999 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:196–197. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Yokoyama T, Aizawa T, Kawaguchi K, Yamaki T, Matsumoto D, Kamijima T, Kamiya M, Kumaki Y, Mizuguchi M, et al. Structural properties of the DNA-bound form of a novel tandem repeat DNA-binding domain, STPR. Proteins. 2008;72:414–426. doi: 10.1002/prot.21939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G, Favre A. 4-Thiouridine as the target for near-ultraviolet light induced growth delay in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;66:1454–1461. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman DG, Ortiz-Lombardia M, Fogg MJ, Koonin EV, Antson AA. Crystal structure of Bacillus anthracis ThiI, a tRNA-modifying enzyme containing the predicted RNA-binding THUMP domain. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb E, Claas K, Downs DM. Characterization of thiI, a new gene involved in thiazole biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4399–4402. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4399-4402.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]