Abstract

The Fanconi anemia (FA) molecular network consists of 15 “FANC” proteins, of which 13 are associated with mutations in patients with this cancer-prone chromosome instability disorder. Whereas historically the common phenotype associated with FA mutations is marked sensitivity to DNA interstrand crosslinking agents, the literature supports a more global role for FANC proteins in coping with diverse stresses encountered by replicative polymerases. We have attempted to reconcile and integrate numerous observations into a model in which FANC proteins coordinate the following physiological events during DNA crosslink repair: (a) activating a FANCM-ATR-dependent S-phase checkpoint; (b) mediating enzymatic replication-fork breakage and crosslink unhooking; (c) filling the resulting gap by translesion synthesis (TLS) by error-prone polymerase(s); and (d) restoring the resulting one-ended double-strand break by homologous recombination repair (HRR). The FANC core subcomplex (FANCA, B, C, E, F, G, L, FAAP100) promotes TLS for both crosslink and non-crosslink damage such as spontaneous oxidative base damage, UV-C photoproducts, and alkylated bases. TLS likely helps prevent stalled replication forks from breaking, thereby maintaining chromosome continuity. Diverse DNA damages and replication inhibitors result in monoubiquitination of the FANCD2-FANCI complex by the FANCL ubiquitin ligase activity of the core subcomplex upon its recruitment to chromatin by the FANCM-FAAP24 heterodimeric translocase. We speculate that this translocase activity acts as the primary damage sensor and helps remodel blocked replication forks to facilitate checkpoint activation and repair. Monoubiquitination of FANCD2-FANCI is needed for promoting HRR, in which the FANCD1/BRCA2 and FANCN/PALB2 proteins act at an early step. We conclude that the core subcomplex is required for both TLS and HRR occurring separately for non-crosslink damages and for both events during crosslink repair. The FANCJ/BRIP1/BACH1 helicase functions in association with BRCA1 and may remove structural barriers to replication, such as guanine quadruplex structures, and/or assist in crosslink unhooking.

Keywords: DNA crosslinking, mutagenesis, crosslink repair, DNA replication forks, chromosomal instability, translesion synthesis, homologous recombination repair

1. Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a multigenic chromosomal instability disorder that is characterized by developmental abnormalities, progressive aplastic anemia, and cancer proneness [1–4]. Here we review our current understanding of how the proteins [5–8] of the FA “pathway”, or more appropriately, “network” [9] control DNA replication and mutagenesis responses to endogenous and exogenous DNA damage. The FANC protein network as detailed in recent reviews [5–7,10] is defined by five sets of interconnected proteins: (a) eight proteins (FANCA,B,C,E,F,G,L,FAAP100) that form an inactive core subcomplex; (b) the FANCM-FAAP24 heterodimer, which possesses DNA translocase activity [11–13] and interacts at damage sites with the core subcomplex to form the larger active core complex [14] containing FANCL E3 ubiquitin ligase activity [15–17]; (c) two physically associated proteins (FANCD2-FANCI heterodimer) that undergo coordinate monoubiquitination by this active core complex [18–20]; (d) two interacting proteins (FANCD1/BRCA2,FANCN/PALB2) that act subsequently to ubiquitination to help initiate homologous recombination repair (HRR) [21,22]; and (e) a BRCA1-interacting helicase (FANCJ/BRIP1/BACH1) [23–26]. The FAAP24 and FAAP100 proteins were identified as FANC-associated proteins [27,28] but have not been linked to mutations in FA patients. An initial study suggested that the FANCM-FAAP24 heterodimer was a constitutive component of the 10-member core complex [7,11], but this inference was based on the properties of the EUFA867 cell line, which may have an additional mutation since it has not been complemented by the FANCM gene. SiRNA depletion studies support the idea that FANCM and FAAP24 are not required for formation of the 8-member core subcomplex [14]. This FANC network of 15 proteins represents more than a simple linear sequence of molecular events and appears to be restricted to vertebrates since lower eukaryotes carry only a few or none of the homologs. It is interesting that the FANCD1, FANCN, and FANCJ, proteins are associated with hereditary breast cancer [21,23,29–31].

The focus of this review is on studies using human FA cells and vertebrate model systems. At the cellular level, the hallmark phenotype of FA cells is pronounced hypersensitivity to agents that produce DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs) such as mitomycin C, diepoxybutane, cisplatin, nitrogen mustard, melphalan, cyclophosphamide and furocoumarins in combination with ultraviolet radiation (UV) exposure [32,33]. Several of these compounds are commonly used in cancer chemotherapy. Early studies focused on the question of whether there is a crosslink repair defect in FA cells [34] with evidence being provided both for [35–38] and against [39,40] this hypothesis. It is noteworthy that the methods of alkaline elution of DNA from filters and gel electrophoresis of denatured-renatured DNA were commonly used to assess crosslink “unhooking” as the putative initial step in repair. These approaches have generally been replaced with more refined assays based on site-specific crosslinks in plasmids, detection of DNA breakage by gel electrophoresis, and immunocytochemical detection of repair protein trafficking in nuclear foci.

One of the themes of this review is that the FANC protein network contributes much more generally to genomic stability than is often appreciated, by overcoming most or all forms of replicational stress, with ICLs being the extreme case. With respect to DNA repair, most FANC proteins function during DNA replication to assist the replication machinery in coping with polymerase-blocking lesions and structural barriers to minimize the occurrence and persistence of double-strand breaks (DSBs) [41,42] that are manifest as chromatid breaks and exchanges at metaphase [43]. Two FANC proteins, FANCD1/BRCA2 and its FANCN/PALB2 partner protein, participate in HRR to mend broken replication forks. During normal DNA replication in untreated cells, a core complex null mutant (such as fancc) and a brca2 truncation mutant behave in an epistatic manner in avian DT40 cells, implying that their common function is to assist in restoring broken replication forks through HRR [44]. Thus, the FANC protein network can be considered a cell’s final defense against potentially mutagenic and carcinogenic damage that has not been removed by excision repair. All DNA base damages and single-strand breaks remaining as DNA replicates must be processed with the help of FANC proteins that both prevent DNA replication fork breakage and restore broken forks by HRR, a higher fidelity mode of DSB repair than nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) [45,46].

The protracted FA molecular saga began with the cloning of FANCC 16 years ago [47]. In 1998 there was no model for how FANC proteins maintain chromosome stability and little insight as to whether they should be viewed as DNA repair proteins [9]. A seminal finding by D’Andrea and coworkers in 2001 was the identification of FANCD2 monoubiquitination [18], a key intermediate step that was initially presumed to be generally required for “pathway function”. However, more recently FANCD2 was found to have a paralog binding and stabilizing partner, FANCI, which is also monoubiquitinated and phosphorylated in response to DNA damage [19,20,48]. FANCI monoubiquitination depends on FANCD2 monoubiquitination [19,20,48], and a converse dependence is seen in human cells [19]. FANCD2 monoubiquitination and focus formation in avian cells, as well as resistance of crosslinking damage, is largely independent of FANCI monoubiquitination [48].

The emerging picture of FANC protein function has become more complex with evidence for branching processes that can separately promote translesion synthesis (TLS) by low-fidelity polymerases [49,50] and HRR, events that require, respectively, core complex formation only [51] or also FANCI-FANCD2 monoubiquitination, which requires core complex formation (models are presented in Section 9). A second key discovery was the identification of FANCM as a DNA-binding protein containing helicase motifs [11,52], thereby providing a candidate protein for damage recognition when replication is blocked. More recent data provide an increasingly detailed picture describing how the FANC proteins mediate highly choreographed and integrated events that occur in response to various DNA damages or other blocks to replication. Specifically for crosslinking damage, FANC proteins also promote an S-phase checkpoint that helps coordinate crosslink repair through the processes of TLS and HRR. These three contributions explain why FA cells are consistently markedly sensitive to crosslinking damage. Moreover, mutagenesis studies in isogenic hamster CHO cells suggest a defect in NHEJ efficiency, as well as HRR, in fancg cells [42]. (Note that mutant genes are written in lower case italics and wild-type genes in uppercase italics.)

Certain FANC proteins have important cytoplasmic roles in redox metabolism [53], hematopoietic cell regulation [54], and probably the immune system [55], but these areas are outside the scope of this review on DNA damage, replication, and repair. However, since several of the core complex proteins are involved in redox metabolism and reducing oxidative stress [56–59], defects in these proteins may result in more spontaneous oxidative DNA damage, thereby impacting DNA replication. This role of FANC proteins might help explain the abnormal oxygen sensitivity of chromosomal aberrations in FA cells [60].

2. Cell survival in response to DNA damage

FA patient cells [33,61–63] and FA model systems invariably show substantial sensitivity to killing by agents producing ICLs, and sometimes show more modest sensitivity to various other DNA-damaging agents and inhibitors of DNA replication (e.g. IR, methylating agents, hydroxyurea) [64–69], suggesting the involvement of the FANC network in general damage mitigation during replication. Only studies using isogenic pairs of mutant and control cells provide an accurate measure of the relative sensitivity of FANC-defective cells to DNA damages. Many studies that addressed the sensitivity of FA cells to UV-C, ionizing radiation (IR), and other mutagens are difficult to interpret because isogenic cell lines were not available, and the inter-individual variability that exists among normal cell lines is a confounding factor [70]. For example, differences in sensitivity of 1.5- to 2-fold measured by cell survival assays between normal and FA cells may represent nothing more than normal population heterogeneity in the absence of overt repair defects. However, examples can be cited where larger differences in sensitivity argue for real biological disparity, for example, as when 3-to 5-fold sensitivity of two FA cell lines was reported for monoadducts produced by 4,5′,8-trimethylpsoralen and 405-nm radiation [37].

The degree of crosslink sensitivity among FANC mutants varies considerably across systems. In human lymphoblasts and fibroblasts, FANC mutants are typically 10- to 20-fold more sensitive [33,61–63], and similar results are seen with the avian DT40 system [52,67,68,71–73]. The CHO KO40 fancg mutant has 2- to 3-fold sensitivity to crosslinking agents compared to 4- to 5-fold sensitivity to methylnitrosourea, methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), and 6-thioguanine [66]. All of these sensitivities were corrected upon transfection of KO40 cells with the hamster Fancg gene. CHO NM3 fancg cells were also fully corrected for mitomycin C (MMC) and MMS sensitivity by hamster Fancg [74]. These results illustrate an important role for FANCG in resistance to various kinds of damage besides ICL damage.

As an instructive comparison of FANC mutants to HRR mutants, Rad51 paralog mutants (xrcc3, rad51d) of CHO cells are 50- to 100-fold sensitive to crosslinking agents (HRR being a necessary component of ICL repair) and 5-fold sensitive to MMS (reflecting the role of HRR in restoring broken replication forks caused by unrepaired damage during DNA synthesis) [75,76]. Similarly, the xrcc2 irs1 V79 hamster mutant is 100-fold sensitive to MMC [77], and this extreme sensitivity is fully complemented by the human gene [78]. It is notable that among numerous DT40 knockout mutants, the rev3 TLS mutant is more sensitive than FANC mutants or any other DNA repair mutants to crosslinking damage [73].

Increased sensitivity to killing by IR has sometimes been convincingly associated with various FANC mutants where isogenic control cells are available [17,66,67,69,72,79,80], although the degree of sensitivity is usually small (< or ≪ 2-fold). Interestingly, the modest IR sensitivity of FANCJ/BACH1-deficient human cells is associated with reduced DSB repair efficiency, based on delayed kinetics of γH2AX foci disappearance [80]. Moreover, IR-induced BRCA1 focus formation is attenuated in fancj cells, which suggests a role for FANCJ in recognizing DSBs arising from IR exposure.

Studies of non-isogenic human FANC mutant fibroblasts did not find IR sensitivity among several complementation groups, including FANCD1/BRCA2 [81,82]. Similarly, a brca2 truncation mutant in avian cells shows no IR sensitivity whereas it is highly sensitive to cisplatin [83]. These data suggest that BRCA2 is not important in HRR acting on direct DSBs produced by IR, but rather acts at broken replication forks.

3. Increased chromosomal instability

Fanconi anemia is one of three prominent classical chromosome instability disorders, which like ataxia telangiectasia and Bloom syndrome has elevated spontaneous chromosomal breakage and rearrangement [84,85]. These three syndromes have chromosomal phenotypes, respectively, of high sensitivity to breakage in response to crosslinking agents [32,86], high sensitivity to breakage by ionizing radiation (IR) [87], and greatly increased spontaneous sister chromatid exchange (SCE) [88]. More specifically, FA cells in mitosis show markedly increased spontaneous chromatid breaks and gaps combined with a modest increase in exchanges [84,86]. It should be noted that in immortalized cell lines, there are instances in which increased spontaneous aberrations are not associated with loss of a FANC protein as in fancg null CHO cells [66] and fancg EUFA143 human lymphoblasts (our unpublished data), which were each compared with isogenic control cells.

Prenatal and postnatal screening for FANC defects is performed using a diepoxybutane test for chromosomal damage [89]. Exposure of FA cells to low doses of MMC produces excessive triradial, quadriradial, and more complex chromosomal interchanges [90] that arise from misjoining of chromatid breaks between nonhomologous chromosomes. Fanca and fancg human fibroblasts are at least 10-fold more sensitive to radial formation than gene-complemented control cells [90].

A significant increase in chromatid breaks was also seen in FA cells treated with the simple alkylating agent ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) under conditions of chronic low-dose exposure [86]. This important observation supports the concept we have been developing that FANC proteins have a global role in chromosome stability that encompasses a broad spectrum of DNA damages or other impediments to DNA replication [42,91].

The accelerated erosion of telomeres seen in FANC mutants [92–94] might be explained by impaired replication [95,96] through structural barriers in telomeres, e.g. guanine quadruplexes [97,98], which can form during DNA replication [99].

4. Assessment of repair defects

4. 1 Crosslink repair assays

The fact that HRR mutants are highly sensitive to ICLs, whereas most mutants in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway exhibit much more modest sensitivity (except those deficient in the XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease, which is thought to be responsible for cleaving the DNA for crosslink unhooking; Fig. 1.5 below), argues that ICL repair in vivo proceeds primarily through a recombination-dependent mechanism that operates during S phase [73,100] (see discussion and references in [101,102]). In a study using the comet assay to assess ICL unhooking (uncoupling) after treatment of diploid human fibroblasts with photo-activated 4-hydroxymethyl-4,5,8-trimethylpsoralen (HMT), data were presented in support of a model in which unhooking can occur in G1 phase followed by further processing in S phase at blocked replication forks [103]. The unhooking was dependent on XPF-ERCC1 but not XPG. However, this model is difficult to reconcile with the known requirement for all NER proteins in ICL unhooking in the absence of DNA replication [101,104] and with the well established fact that only ercc1 and ercc4/xpf mutations confer high sensitivity to killing by crosslinking agents. Most evidence supports the concept that ICL recognition and repair in cycling cells occurs primarily in the context of DNA replication [6,100,105], with ICL unhooking in G1 cells making a minor or insignificant contribution (see below).

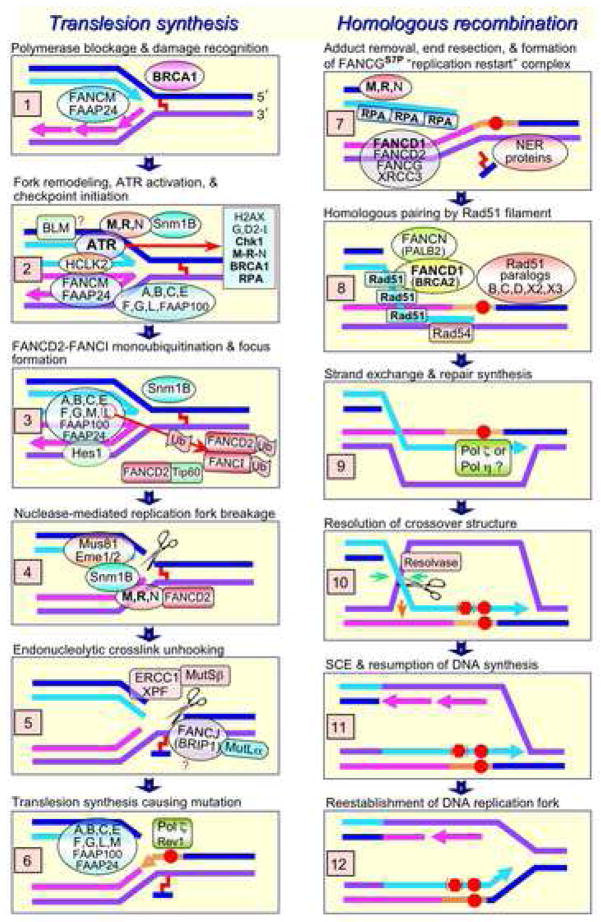

Fig. 1.

Heuristic model showing participation of the FANC proteins in the two components of ICL repair that occurs at blocked replication forks. Proteins written in bold font are known to be essential for the viability of proliferating vertebrate cells: ATR [268], Chk1 [269], Mre11 [270], RAD50 [271], BRCA1 [272], RPA [273], FANCD1/BRCA2 [274], and Rad51 [275]. (DT40 nbs1 null cells are viable but grow slowly [276]; in the mouse only nbs1 truncation mutants are viable [277].) Events may not occur exactly in the order shown. (1) ICLs can arise endogenously such as from the metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde [278] and are produced by many cancer chemotherapeutic agents. (2) The blocked replication fork with a possible requirement for RPA [279] activates the ATR kinase, which directly phosphorylates FANCG [214], the FANCI-FANCD2 complex, and Chk1 [19,183]; Chk1 subsequently phosphorylates FANCE [188]. Reversal of the blocked fork is proposed, based on the properties of the FANCM-FAAP24 translocase and BLM as discussed in the text. (3) FANCM-FAAP24 together with the FANC core subcomplex (A,B,C,E,F,G,L,FAAP100) (see Introduction) mediate the monoubiquitination of the FANCI-FANCD2 complex through the ubiquitin ligase activity of FANCL [15,17], an event that is necessary for replication-associated HRR to occur efficiently. The recently described Hes1 protein shares properties with core complex proteins and is also necessary for FANCI-FANCD2 monoubiquitination [219]. The chromatin remodeling protein Tip60 (a histone acetyltransferase) interacts with FANCD2, is epistatic with FANCC for MMC sensitivity, and is not required for FANCD2 monoubiquitination or focus formation [280]. (4) Repair of the ICL requires endonucleolytic cleavage on the 3′ side by the Mus81-Eme1 (and possibly Mus81-Eme2) complex [226,235]. (5) ICL release is enabled by endonucleolytic incision by XPF-ERCC1 on the 5′ side of the ICL, an event that is speculatively mediated by the helicase activity of FANCJ (also known as BRIP1 and BACH1). (6) The resulting gap provides a substrate for error-prone polymerases such as Pol ζ (Rev3-Rev7 complex) and the tightly associated Rev 1 [281]. The FANC core subcomplex is required for this mutagenic step and for Rev1 focus formation [51]. DNA synthesis likely produces a base substitution mutation (red circle). (7) The one-ended DSB is processed in preparation for HRR, an event that is thought to require the nuclease activity of the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex. The NER machinery can excise the monoadduct when it becomes physically accessible. The FANCGS7P putative ”replication restart” complex (FANCD1-FANCD2-FANCG-XRCC3) assembles to help initiate HRR [214]. (8) Rad51 nucleoprotein filament formation requires BRCA2 and PALB2 (FANCD1 and FANCN, respectively) and is followed by homologous pairing. (9) Strand exchange results in the formation of a D-loop, a substrate that can prime DNA synthesis, which perpetuates the mutation shown by the red circle. Since this synthesis may well be performed by a TLS polymerase (see text), another base substitution mutation (red hexagon) can arise with a much higher probability (i.e. 0.1–3%) than for a normal replicative polymerase (~10−9) [49,50]. (10) The crossover structure is processed by the nuclease activity of a resolvase, which results in a SCE if the crossover strands are incised as shown by the green arrows. Incision at the orange arrow would not cause SCE. (11–12) The replication fork is reestablished and replicative synthesis resumes.

Several experimental approaches have assessed repair in plasmids carrying site-specific crosslinks, initially with non-replicating plasmids. In a psoralen-crosslink repair-synthesis assay conducted in cell extracts with damaged plus undamaged donor plasmid, fanca, fancb, and fancc mutants, as well as the xpa, xpc, and xpg excision repair mutants, showed only modest (or no) reduction in repair capacity while ercc1, ercc4/xpf, and msh2 mutants showed substantial reductions [106,107]. Subsequent studies employed reporter gene reactivation assays in which a specific-site ICL was introduced into GFP- and luciferase-expressing plasmids in order to block transcription of the reporter gene, which contained an ICL between the promoter and open reading frame [101,104]. These studies showed that, in the absence of homologous donor sequence, repair of ICLs was accomplished by recombination-independent mechanisms that depend strongly on all NER factors.

In a recent study, Legerski and coworkers utilized a plasmid ICL repair assay with an ECFP reporter gene containing an inactivating psoralen crosslink flanked by a frameshift mutation, along with a promoterless inverted repeat of ECFP [108]. Gene expression only occurs when uncoupling of the ICL is followed by repair of the frameshift mutation via homology-dependent recombination. The psoralen ICL stimulated homologous recombination only when the plasmid was linearized by induction of a DSB located near the ICL, a configuration designed to mimic a broken replication fork. Stimulation of gene reactivation by the ICL was dependent on ERCC1-XPF endonuclease, MSH2, REV3, and the FANC proteins FANCA, G, and D2, as well as the HRR proteins XRCC2 and XRCC3. These results showed that the DSB stimulated ICL repair, suggesting that replication fork collapse is a necessary step for the efficient repair of these lesions. We note that the quantitative differences between mutant and control cell lines in this assay are only 2–4 fold, as compared with typical 10- to 20-fold differences in chromosomal and survival endpoints seen in FA cell lines. This quantitative discrepancy suggests that much of the reactivation activity detected in this assay is occurring through processes, such as intermolecular single-strand annealing, that are largely irrelevant to what happens at broken replication forks.

Lambert and co-workers developed an assay in which extracted chromatin-associated proteins are incubated with a 32P-labelled 140-bp substrate containing a site-specific 4,5′,8-trimethylpsoralen (TMP) cross-link [109]. Protein extracts from human FA-A, B, C, D2, F, or G lymphoblastoid cells showed a reduced efficiency of both 5′ (8–33% of normal) and 3′ (22–71% of normal) incisions made on the furan side of the ICL, with FA-G cells having the largest reductions [109,110]. Levels of incision were restored in corrected FA-A, C, and G cells, and antibodies against FANCA, FANCC and FANCG inhibited these incisions. It was proposed that the XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease mediates the incisions [111], that the FA proteins are involved in the initial recognition/incision process, and that the chromatin structural protein nonerythroid α-spectrin provides a scaffold to recruit the proteins involved [112]. FANCA and FANCF co-localize with α-spectrin in ICL-induced nuclear foci, several FA proteins co-immunoprecipitate with α-spectrin [112–114], and FANCG directly interacts α-spectrin in a yeast two-hybrid assay [115]. The significance of these dual incisions in cell extracts is unclear when one considers that only 3–4% of the total substrate is incised in normal extracts, and particularly in light of conflicting findings of proficient incision of ICLs in FA cells [103] and extracts [101]. However, Lambert argues that the induction of apoptosis might mask an incision defect in FA cells [110].

4. 2 Double-strand break repair assays

A provocative study measuring the rejoining of linearized plasmid in nuclear extracts reported a 4-fold reduced rejoining efficiency for FA cells in a reaction that was independent of the NHEJ protein XRCC4 [116]. The rejoined products from FA cell extracts also had a higher proportion of deletions. Subsequent cellular studies of DSB rejoining have yielded varied and sometimes conflicting results as follows.

Studies by Papadopoulo and coworkers examined the in vivo rejoining of transfected plasmids carrying DSBs produced by restriction enzymes [117,118]. Lymphoblasts derived from several FA complementation groups showed a normal frequency of rejoining, but the processing of blunt-ended DSBs was error-prone in the sense of having in a higher deletion frequency and larger average deletion size; the fidelity of cohesive end joining was not impaired in FA cells. In the case of FA-C cells, the defect in the quality of blunt-end rejoining was eliminated in FANCC-complemented cells [118]. In apparent conflict with these lymphoblast studies, Campbell and coworkers reported 5- to 10-fold reduced rejoining frequencies of transfected linearized plasmids (both cohesive- and blunt-ended) in FA fibroblasts compared with normal and cDNA-complemented control strains [119]. FA strains also consistently showed higher sensitivity to killing by chromosomal DSBs produced by transfected PvuII restriction enzyme [119]. Fancc and fancg rodent cell mutants showed similar high sensitivity to restriction enzyme-induced cell killing, but an attempt to reproduce this finding in isogenic fancg CHO cells gave negative results [91]. In immortalized mouse fibroblasts, a fancd2 knockout mutation showed sensitivity to killing by restriction enzymes when tested on a dna-pkcs/prkdc (scid) double-mutant genetic background, but the phenotype of fancd2 cells was not examined [120].

Campbell and coworkers also presented intriguing data showing highly elevated (~10-fold) levels of Rad51 and Mre11 proteins in fanca, fancc, and fancg (but not fancd2) fibroblasts [121]. The FANC mutants having elevated Rad51 protein also showed ~10-fold increased levels of HRR activity measured using transfected plasmids that detect intra-molecular recombination events [122]. These provocative results are difficult to reconcile with the many studies using chromosomally integrated substrates in both human cells [25,123] and model systems [67,71,72,124] that found either a reduced efficiency of HRR or no change in efficiency [52,125,126]. It is notable that a normal level of Rad51 protein was found in FA-A and FA-G fibroblasts by another laboratory [127], and in FA-C lymphoblasts in the absence or presence of DNA damage [128].

Subsequent work from Campbell’s laboratory using transfected plasmids and restriction enzymes implicated the FANCA, C, and G proteins in an alternative DSB rejoining pathway that requires the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex and the NHEJ protein LIG4 but not DNA-PK or XRCC4 [129]. The relevance of these observations using synthetic substrates that are not chromosomally integrated is unclear, but they are consistent with the report cited above that fanca mouse cells are hypersensitive to killing by transfected restriction enzyme in the absence of DNA-PK activity [120].

A defect in DSB rejoining measured by gel electrophoresis after 10–30 Gy IR exposure was reported for both FA lymphoblasts (fanca, fancc, fancg) and mouse fanca splenocytes [130]. However, surprisingly the survival of fanca lymphoblasts was normal, and mouse fanca bone marrow progenitor cells showed only slightly increased radiosensitivity in a clonogenic assay.

4.3 Rejoining efficiency and fidelity in V(D)J assays

Studies using V(D)J recombination assays suggest the possible involvement or influence of FANC proteins in this NHEJ-mediated recombination process. Papadopoulo and coworkers examined V(D)J coding and signal joint formation in lymphoblasts from normal and FA individuals of complementation groups C and D1 [131]. Control and mutant cells had similar rejoining frequencies, but the frequency of imprecise rejoining at coding joints was 5- to 9-fold elevated in FA cells. These aberrant junctions in FA cells were consistent with increased exonucleolytic degradation of DNA ends prior to ligation and possibly also abnormal cleavage by the Rag1-Rag2 complex [131]. The precision of signal joint formation in FA cells was not obviously altered.

Campbell and coworkers found that the frequency of signal joint formation was normal in fancc fibroblasts, but there was a 8-fold increase in the proportion of imprecise joints, which were often associated with deletions [132]. HT1080 tumor cells expressing a dominant negative FANC mutant allele had a similar phenotype, as did HT1080 cells transfected with FANCD2 antibody. However, the dominant negative mutant did not show a defect in the efficiency or precision of coding joint formation.

5. Sister-chromatid exchange (SCE)

5.1 Spontaneous and induced

In vertebrate cells, SCEs are recombination events between parental DNA strands that are visualized in metaphase cells [133] and occur when broken DNA replication forks are restored by HRR [134] or possibly when gaps in synthesis of the lagging strand are repaired by HRR between sister chromatids [135]. In a literature review in 1982, Evans concluded that the rate of spontaneous SCE in cells from FA patients is normal [136], in marked contrast to Bloom syndrome in which they are greatly elevated [88]. Subsequent studies have largely confirmed that conclusion [137] although both modest increases [138] and decreases [139] in SCE frequency among FA cells have been reported, which likely reflects normal genetic variation in the human population. In hamster cells, there are two reports using mutants to analyze SCE. Two CHO fancg mutants [66,140] and a V79 brca2 mutant [141] did not differ from their gene-complemented controls in SCE frequency. We are unaware of any analogous studies using isogenic human FA cells.

The high sensitivity of FA cells to chromosomal aberrations and cell killing by DNA ICL agents such as MMC is distinct from their sensitivity to induced SCE. Some studies found no appreciable change in sensitivity to crosslink-induced SCEs in FA cells [82,137,142], but examples of both modestly decreased levels [139,142] and increased levels [138,143] are also noted. In a study by Latt and coworkers [142] FA lymphocytes and fibroblasts behaved differently; lymphocytes had a reduced MMC-induced SCE response while fibroblasts did not. Given the universally high cytotoxicity of FA cells in response to ICLs, there are inherent technical complexities and limitations in performing the SCE assay in which cells are generally required to reach the second mitosis after exposure to be scored (see comments in [141]).

Limited data are available for SCE induction in FA cells by other DNA damaging agents or inhibitors of DNA replication. In Latt’s study [142], FA lymphocytes consistently had lower levels of EMS-induced SCEs than control lines. A study using aphidicolin, an inhibitor of Polα, increased SCEs were seen in normal and FA lymphocytes to a similar extent whereas chromosomal breakage was increased 4-fold versus 20-fold, respectively [144]. Since aphidicolin presumably causes replication fork breakage, the normal response of FA cells to aphidicolin-induced SCE would seem inconsistent with a model in which the FANC protein network promotes the restart of broken forks by HRR, the molecular process presumably responsible for SCE [42,91]. This paradox is addressed in the next two sections.

5.2 Discordance between mammalian and avian systems

One of the consistent features of avian DT40 FANC mutants is a marked increase in spontaneous SCE [145]. Both fancc and fancd2 DT40 knockout mutants showed a ~2-to 4-fold increased spontaneous SCE [67,68]. In two studies, double mutants of FANCC and Rad51 paralogs (mutants fancc-xrcc2 and fancc-xrcc3) showed that the increased SCE in fancc cells was dependent on the HRR proteins Xrcc2 and Xrcc3 [68,72]. It is noteworthy that recombination pathways in the DT40 system [146] also differ from mammalian cells with respect to the SCE phenotype of Rad51 paralog mutants. For example, in studies using isogenic cell lines, hamster and mouse knockout rad51d mutants showed no change in spontaneous SCE rate [76,147] whereas the DT40 rad51d mutant had reduced SCE [148]. The differing SCE phenotypes of mammalian vs. DT40 fanc mutants is not yet understood but may be related to the fact that DT40 cells have very active homologous recombination as measured by gene targeting (~10% efficiency).

5.3 Implications of normal SCE for models of FANC protein function

In the models we have put forth [42,91,149] and refined in this review (Section 9), the role of the FANC protein network is both to promote TLS at stalled/blocked replication forks and to promote HRR at broken replication forks. A priori the defect in the latter process could reasonably be expected to result in reduced spontaneous SCE (assuming that SCEs result from restarting broken replication forks via HRR), which is not what is observed (as mentioned above the same conundrum applies to Rad51 paralog mutants.) This finding suggests there is more than one pathway of HRR that participates in restarting broken replication forks. A subpathway not resulting in SCE may be what is impaired in FANC mutant cells. An alternative explanation involves a compensatory change in FANC mutant cells that shifts the orientation of resolution of Holliday junctions in favor of more crossover products that represent SCEs. However, this possibility might seem unlikely because the compensatory change would have to occur exactly to the extent needed to keep the SCE level from changing [66]. A third possibility is that a higher rate of spontaneous fork breakage occurs in FANC mutants because of deficient TLS at blocking base damage and that this increase offsets the deficiency in HHR. This possibility could explain the increased SCE in avian FANC mutants mentioned above.

6. Spontaneous and induced mutagenesis

6.1 Human in vitro systems: HPRT, ATP1A1, PIG-A, and supF loci

The first suggestion of aberrant mutagenesis in FA cells was in a 1977 meeting Abstract in which FA fibroblasts reportedly showed no HPRT mutation induction by EMS [150], a potent base substitution mutagen. Milestone studies in 1990 by Papadopoulo and coworkers [151,152] found that fanca and fancd1 lymphoblasts were defective (≥ 3-fold reduced efficiency) in the induction of HPRT mutations by photo-activated psoralens. (Note: The lymphoblast line HSC62 used in these studies was reassigned from complementation group B [152] to group D1 [21,153].) In fanca cells, reductions in mutagenesis were seen with TMP and 8-methoxypsoralen treatments [151], and in fancd1 cells reductions were seen after treatment with both TMP plus 365-nm or 405-nm UV radiation, conditions which produce crosslinks plus monoadducts or only monoadducts, respectively [152]. Remarkably, at the Na+/K+–ATPase (α-subunit) (ATP1A1) locus, mutations detected by ouabain resistance, which is thought to specifically measure base substitution events, were essentially not induced at all in fanca cells treated with TMP plus 365-nm UV radiation [151].

Hprt mutants isolated from fancd1 cells showed a pronounced shift from point mutations (changes not detectable by Southern blotting, or specifically base substitutions in later sequencing studies) to intragenic deletions and gene rearrangements. After 365-nm irradiation, the percentage of point mutations among identifiable mutants was 84–90% in control cells compared to 22–38% in fancd1 cells [152,153]. After 405-nm irradiation (which produces only monoadducts) the values were 100% point mutations in controls versus 40–60% for fancd1 cells [152,154]. The types of base substitutions identified in fancd1 cells and their distribution with the HPRT gene were the same as those in the control cells [154]. Similarly, for spontaneous HPRT mutants the percentage of point mutations was 67% in control cells versus only 23% in fancd1 cells [152]. In these experiments FA cells were ~2-fold more sensitive than controls to killing (measured by colony formation) in response to both treatments [151,152]. This similarity helps emphasize that FA cells are not specifically sensitive to ICL damage. These studies do have notable experimental caveats, as they were performed with non-isogenic cell lines and a significant fraction of the mutants analyzed in mutagen treated populations were spontaneous in origin [154].

In an attempt to discern the mechanism underlying formation of HPRT intragenic deletions in FA cells, eleven independent mutants from spontaneous and induced cultures of fancd1 cells were found to have several interesting features [155]: (a) one or both breakpoints identical in two or more mutants; (b) the presence of a consensus heptamer sequence, normally associated with V(D)J recombination, close to the breakpoints; and (c) 2–4 bp sequence homologies usually at each breakpoint, one of which was retained in the mutant junction. The authors suggested that the FA defect causing chromosomal instability results in illegitimate (aberrant) site-specific cleavage activity [155]. It would be of interest to learn whether this pattern is seen in other FA lymphoblasts and cell types.

The X-linked PIG-A locus encodes a subunit of an enzyme essential for an early step in the biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) [156]. PIG-A mutant cells do not express the set of proteins that require GPI for attachment to the cell surface, resulting in cells with a “GPI-negative phenotype.” In cultured lymphoblasts the PIG-A spontaneous mutation rate, which can be measured by flow cytometry, was found to be elevated in six FA cell lines by a remarkable >30-fold on average [157]. This finding is consistent with the concept of increased rate of PIG-A deletion in FA cells, although the mutants have not yet been characterized.

In a pSP189 shuttle-vector-based SupF mutation assay, FA core complex proteins FANCA and FANCG, but apparently not FANCD2 or FANCI, were necessary for efficient spontaneous and UV-C induced mutagenesis in SV40 immortalized fibroblasts [51], a finding that is consistent with the conclusions from studies based on endogenous chromosomal loci. For example, the spontaneous SupF mutant frequency was 3-fold higher in FANCG-corrected cells than in fancg cells, which was a highly significant difference [51]. The loss of mutations in this assay can be attributed to a decreased rate of successful plasmid replication, and thus loss of a potential SupF mutant, in the absence of an intact core complex. In this study, core complex mutants also had impaired nuclear foci formation for the TLS polymerase Rev1. A study based on a psoralen-damaged pZP189 shuttle vector found no difference between FA and control cells for induced mutation frequency, but the two FA cell lines had a much higher percentage (50%) of deletions in the SupF target gene [158].

6.2 Human in vivo systems: HPRT and GPA loci

A few studies have measured mutation frequency in blood cells taken from FA patients [159,160]. FA and normal patients had similar frequencies of HPRT mutations assayed in vitro in T-lymphocytes although there were large variations in each group [159]. In contrast, mutant frequencies at the glycophorin-A (GPA) locus in FA erythrocytes were elevated 8- and 30-fold for NN allele conversion and NØ allele loss mutations, respectively [159]. The authors attributed this difference between the HPRT and GPA loci to diminished viability of FA HPRT deletion mutants in the colony formation assay. (Although differences in mutation frequency are likely to reflect differences in mutation rate, there will not be a simple correlative relationship between them.) In a subsequent study, the HPRT mutation spectrum was determined in T-lymphocytes from nine FA patients. A much higher percentage of deletions (74%) was seen for the FA patients compared with 36% for the healthy-donor controls [161]. Thus, both the GPA and HPRT assays provide in vivo confirmation of the elevated frequencies of deletions seen in FA cells in vitro [152].

6.3 Hamster CHO system: HPRT and ATP1A1 loci

CHO cells have the unique set of advantages of high plating efficiency, fast growth rate in both suspension and monolayer culture, lack of metabolic cooperation [162] in HPRT mutation assays, and rapid cell death under selective conditions at high cell density. The high experimental precision achievable with CHO cells enabled accurate determination of spontaneous mutation rates in fancg null versus gene-complemented control cells. In Luria-Delbrück fluctuation experiments [163] fancg mutant cells were found to have a >3-fold reduced HPRT mutation rate, which was attributed to increased lethality of cells undergoing multigenic deletions or other chromosomal rearrangements in the vicinity of HPRT [42]. The frequency of HPRT mutants induced by three diverse agents (γ-rays, UV-C radiation, and ethylnitrosourea) was also consistently reduced in fancg cells [91]. In marked contrast to the fancg mutant, an HRR-defective rad51d isogenic null mutant, had a 12-fold increased rate of spontaneous HPRT mutations [76] caused by increased deletions, many of which were intragenic events [42]. This enhanced mutagenesis phenotype in rad51d cells is attributed to efficient repair of DSBs by NHEJ following replication fork breakage and the completion of replicon synthesis. In fancg cells this compensatory NHEJ process appears to be defective because the modestly increased percentage of NHEJ-associated deletions did not compensate for the reduced rate of base substitution mutation [42].

There was a shift in the HPRT mutation spectrum from 40% deletions in Fancg-complemented control cells to 62% in fancg cells; base substitutions decreased from 31% to 21%, respectively [42]. This value of 31% is similar to the 38% base substitutions reported in the K1 strain of CHO cells [164]. A study of mutagenesis at the ATP1A1 locus found the spontaneous mutation rate in fancg cells to be reduced by ~2-fold, and the ENU-induced mutation frequency was also significantly diminished by <2-fold (J. Hinz and L. Thompson, unpublished results). This finding agrees qualitatively with that from human lymphoblasts discussed above and supports a model in which base-substitution mutagenesis is diminished in FANC core complex-defective cells (see Fig. 2A in Section 9). Thus, one role of the FANC proteins is to promote mutagenic TLS at a wide variety of lesions that block replicative polymerases. The much higher percentage of spontaneous base substitutions seen in human lymphoblasts versus CHO cells might be due to reduced efficiency or reliance on TLS in CHO cells or by differences in the level of spontaneous damage. We also note that CHO cells express mutant Tp53 protein [165,166] whereas the human lymphoblasts do not.

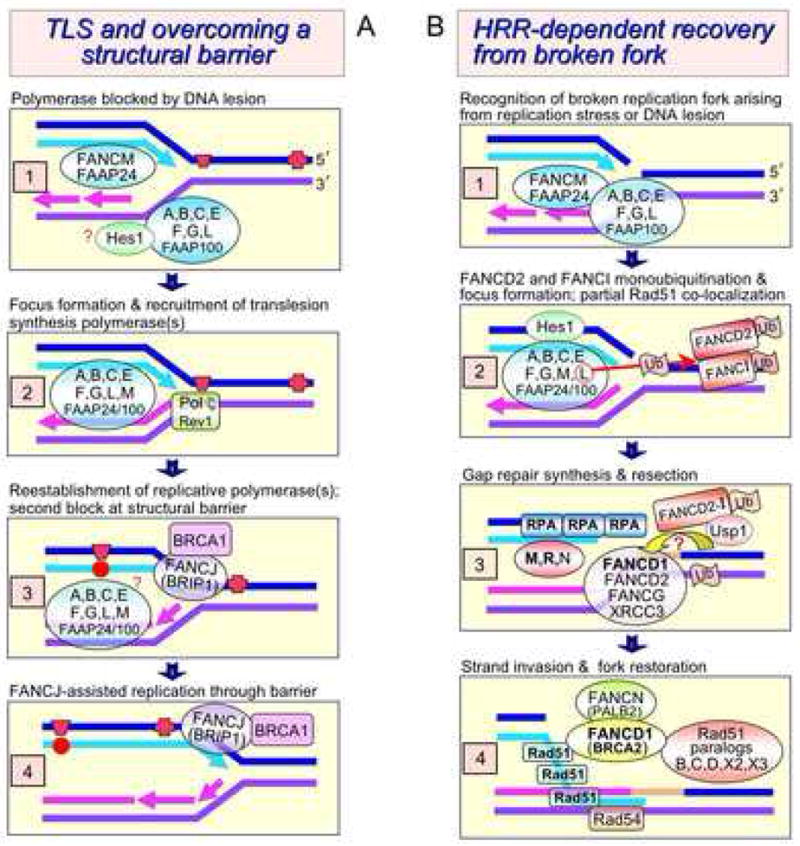

Fig. 2.

Models depicting the involvement of FANC proteins in TLS, resolving a structural barrier, and HRR. A. (1) A replication fork encounters a blocking lesion such as a chemically modified base other than a DNA crosslink (red trapezoid). (2) The FANC core complex recruits TLS polymerases. (3) The lesion is bypassed with likelihood of a base substitution (red circle). Then the replication fork independently encounters a structural barrier, such as a telomeric G4 or other secondary structural motif (red cross). (4) FANCJ helicase activity, acting alone or in concert with the core complex, alleviates this obstacle. B. (1) A replication fork has collapsed from enzymatic action [258] or spontaneous breakage as when encountering a nick or gap. (2) FANCM-FAAP24 senses the damage, and the active core complex monoubiquitinates FANCD2, which becomes associated with chromatin. (3) A putative “replication restart” FANC-HRR transition complex (same as shown in Fig. 1.7) containing FANCD1, FANCD2, FANCG, and XRCC3 forms [214]. We speculate this step is promoted by the deubiquitination of FANCD2-FANCI by Usp1 [282,283]. (4) HRR proceeds.

6.4 Gene amplification at CAD and DHFR loci in fancg CHO cells

Gene amplification is a form of mutation that occurs frequently in tumor cells in vivo and in vitro [167,168] and is likely a consequence of defective Tp53 function [169,170]. A recent study found 10 to 40 amplicons per cancer cell genome, indicating that this process contributes substantially to oncogene activation [171]. Gene amplification at the extensively studied dhfr locus (measured by methotrexate resistance) and the CAD (carbamyl-P-synthetase, aspartate transcarbamylase, dihydro-orotase) locus (measured by PALA resistance) was increased 3-fold in fancg CHO cells compared to wild type and gene-complemented control cells [42]. This finding is consistent with the idea that DSBs arising during DNA replication in fancg cells are aberrantly repaired. CHO cells defective in Rad51D [76] and DNA-PK [172] also have elevated gene amplification, suggesting that the increased amplification in fancg cells is a consequence of both diminished HRR, diminished NHEJ, or both.

7. Checkpoint defects

7.1 S phase

FA cells have well-documented abnormal cell-cycle parameters in which the percentage of cells having G2-phase DNA content is increased. (Whether the cells in this expanded compartment are really physiologically in G2 or very late S has not been addressed.) This expanded G2 may account for the reduced growth rate of FA cells [66,173,174]. In response to ICL damage FA cells consistently show increased accumulation in G2 [175–178], which reflects a functional G2 checkpoint that responds to the damage remaining after DNA replication.

Several studies show that DNA synthesis in FA lymphoblasts (groups A, B, C, D1, D2) is resistant (i.e. continues at a normal rate) after ICL damage [179–182] produced by diepoxybutane or psoralen + UV-A (PUVA), which gives a mixture of monoadducts and ICLs. FA lymphoblasts fail to exhibit the dose-dependent inhibition of DNA synthesis that occurs in normal cells, and they undergo accumulation in G2 as a consequence of unprocessed replication-associated damage [179,181]. The degree of G2-phase arrest of FA cells is proportional to the amount of crosslinking, as compared to monoadducts, as shown by the double UV-A exposure protocol in which the second dose converts monoadducts to ICLs after psoralen is removed from the medium [179]. Twenty-four hours after psoralen photo-treatment the fraction of S-phase-arrested cells was 4- to 15-fold lower in FA than in normal cells at equal or equitoxic doses of 4,5′,8-trimethylpsoralen + UV-A [179]. The damage specificity of the resistant DNA synthesis in FA cells was further shown by comparing the PUVA response to that of MMS, which resulted in the same degree of dose-dependent inhibition of synthesis in FA-C cells as in normal and gene-complemented control cells [180]. Another study, in which the size distribution of newly synthesized DNA was examined 3 hr after diepoxybutane treatment, found that the inhibition of thymidine incorporation in fancc cells was due to reduced DNA elongation, not replicon initiation [182]. Collectively, these studies suggest that FA cells defective in the core complex have a S-phase checkpoint defect that appears to be specific for ICL damage.

Mechanistic insight into how the FANC proteins participate in an S-phase checkpoint for ICL damage is emerging. The inhibition of DNA synthesis in response to crosslinking is mediated by the ATR kinase [183]. An analysis based on mutant cell lines and siRNA knockdowns led to the conclusion that the ICL-induced replication checkpoint has two components, one mediated by ATR-Chk1 and the other mediated by ATR-Nbs1-FANCD2 [183]. It is noteworthy in this regard that a previous study had found that Nbs1 of the MRN complex interacts constitutively with FANCD2 [184]. The ATR-Nbs1-FANCD2 branch of the ICL checkpoint requires FANCC, G, and D2 (and probably other core complex proteins) [183]. In addition to being monoubiquitinated in response to crosslinking damage, the FANCD2 protein is phosphorylated by ATR in a reaction that also requires the FANC core complex as well the phosphorylation of Nbs1 at Ser343 [185]. Importantly, the localization of MRN complex into nuclear foci after ICL formation was reported to require the FANC core complex (based on analyzing fanca, fancc, and fancg lymphoblasts) [128].

A new participant in the replication checkpoint in response to crosslinking damage (but not IR) is Snm1B [186,187], which also mediates replication fork collapse as discussed in Section 9. Snm1B-depleted cells lack the normal suppression of DNA synthesis in response to MMC, have normal FANCD2 monoubiquitination, show defective phosphorylation of Nbs1S343, but curiously have normal Chk1S317 phosphorylation [187].

There is evidence that FANC core complex proteins may participate in the replication checkpoint evoked by ICL damage. The ATR target Chk1 phosphorylates the FANCE subunit on two conserved sites (threonine 346 and serine 374). These modifications were reported to be required for MMC resistance through a function that is independent of FANCD2 monoubiquitination in human cells [188] although we note that in avian DT40 cells the loss of these phosphorylation sites did not influence sensitivity to crosslinking damage (M. Takata, personal comm.).

An insightful study by Boulton and colleagues implicates the helicase/translocase activity of FANCM as being essential for efficient ATR-Chk1 signaling in response to inhibition of replication, i.e. spontaneous damage, hydroxyurea arrest, or UV-C photoproducts [189] (crosslinking was not studied). This checkpoint function of the FANCM-FAAP24 complex depends on its translocase activity and its constitutive interaction with the HCL2K checkpoint protein within chromatin, and is independent of the FANC core subcomplex and FANCD2 monoubiquitination [189,190]. Thus FANCM-FAAP24 appears to have two separate roles: (1) sensing damage and facilitating ATR-Chk1 checkpoint activation, perhaps by structural remodeling of blocked replication forks, and (2) recruiting the FANC core subcomplex onto chromatin [14,191], where it can monoubiquitinate FANCD2-FANCI [14].

In studies of SV40-immortalized FA fibroblasts, it was concluded that phosphorylation of FANCD2 at specific residues is required for the IR-induced S-phase checkpoint that causes inhibition of replicon initiation [192,193]. A study of fancd2 lymphoblasts and a FANCD2-corrected derivative found similar results [194]; it also reported increased sensitivity of fancd2 cells to killing by IR and restoration of resistance in gene-complemented cells. Since the FANCC protein is not required for this S-phase IR checkpoint [182,192,195], the checkpoint must not require FANCD2 monoubiquitination. An IR-induced S-phase checkpoint defect was also seen in vivo in Drosophila fancd2 cells using an eye-specific RNAi knockdown procedure [196]. In C. elegans, fancd2 mutants were normal for a hydroxyurea-induced replication checkpoint assessed by the reduced number and enlargement of mitotic nuclei in the germline [197].

Contrary to the preceding observations on IR sensitivity and checkpoint deficiency in immortalized cells, as mentioned in Section 2, three diploid fancd2 fibroblast strains showed IR sensitivity (measured by loss of colony-forming ability) within the range of the normal strains [82]. Moreover, there was no defect in the ATM-mediated S-phase checkpoint in primary mouse fancd2 embryonic fibroblasts [198]. Both the IR sensitivity and the intra-S checkpoint defect seen in SV40-immortalized PD20 fancd2 cells may well be an artifact of the immortalization process in which the SV40 T antigen attenuates Mre11 focus formation [199]. Thus, the putative existence of an intra-S checkpoint defect in fancd2 cells requires confirmation in diploid human cells. Furthermore, the biological significance of this checkpoint remains hypothetical since a case was reported for ATM-defective cells in which restoration of radioresistance to killing was uncoupled from radioresistant DNA synthesis [200].

7.2 G2 phase

Several FANC proteins are reported to participate in the G2 checkpoint. The FANCM-FAAP24 complex discussed above was shown to be necessary for minimizing nuclear abnormalities, supernumerary centrosomes, and γH2AXS139-P and RPA32T21-P foci that arise from spontaneous DNA damage during DNA replication [189]. FANCM- or FAAP24-depleted cells also fail to execute a G2 checkpoint in response to IR [189].

FANCC is implicated in maintaining the G2 checkpoint induced by high doses of IR (5-10 Gy) in both mouse and human cells and is needed for persistent phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc2 required to maintain activation of this checkpoint [195]. These results are intriguing because a physical interaction between FANCC and Cdc2 was reported earlier, and this interaction was abolished in an FA patient-associated FANCC L554P mutant protein [201]. However, another study concluded FA cells had a normal G2 checkpoint in response to IR and hydroxyurea [202]. Thus, the biological significance of a putative FANCC-dependent checkpoint function remains to be established by evaluating cell survival or chromosomal endpoints at low, physiologically relevant doses of IR in G2-exposed cells.

BRCA1 is required for the G2 checkpoint in response to IR [203–205]. BRCA1’s interacting partner, FANCJ/BACH1, is also required for optimal checkpoint activation, which depends on the phosphorylation-dependent interaction between the two proteins [205].

8. Insights from FANCD2 and RAD51 nuclear foci analysis

8.1 Differential capacity of FA cells to form Rad51 foci

Rad51 focus formation, which is generally presumed to reflect the formation of a Rad51 nucleoprotein filament, has been used to address the question of whether FA cells are defective in HRR. After DNA is damaged, nuclear Rad51 foci form over a period of several hours [206,207] in a BRCA2-dependent [126,208,209], BRCA1-independent manner during an HRR process that may be an underlying cause of G2 delay [210]. In one IR study, focus formation (based on percentage of cells having ≥1 focus) was substantially reduced in fibroblasts of eight FA complementation groups in comparison to control cells [127]. However, other investigators analyzing fibroblasts and lymphoblasts as percentage of cells having ≥5 foci did not confirm these results, but rather found that only the FA-D1 complementation group had a defect, which was very pronounced for both IR and MMC exposure [126,211,212]. However, these results with MMC [211,212] are at odds with an analysis of MMC-induced Rad51 foci in FA-C lymphoblasts and their gene-corrected control [128]. In this case, in which the number of foci per cell was scored, FA-C cells had a greatly attenuated MMC-induced foci response but an essentially normal IR-induced response.

The conflicting results with regard to the capacity of fancd2 mutant cells to form Rad51 foci in response to IR [127,211,213] deserves further comment since FANCD2 associates with BRCA2 in chromatin [213] and was recently identified within a complex containing BRCA2, FANCG, and XRCC3 [214]. Defective Rad51 focus formation in PD20 fancd2 SV40-immortalized cells [213] was not confirmed in four other studies that included this cell line, other SV40-immortalized cells, primary fancd2 fibroblasts, and mouse fancd2 knockout cells [44,126,198,212]. Similarly, Rad51 focus formation is normal in fancd2 (and fancc) avian DT40 cells in response to both IR and MMC [44,67], and Rad51 foci co-localized with the phosphorylated form of histone variant H2AX, called γH2AX [44], which is produced at DSB sites. D’Andrea and coworkers also reported defective BRCA2 focus formation in fancd2 cells, as well as in fanca and fance cells [213]. However, a defect in BRCA2 focus formation would be inconsistent with a phenotype of normal Rad51 focus formation found in most studies using several fancd2 and core complex mutants. Finally, their conclusion of a deficiency in the loading of BRCA2 onto chromatin in fancd2 SV40-immortalized mutant cells in response to MMC treatment [213] differs from a subsequent report in the DT40 system showing normal loading of Rad51 onto chromatin in fancc and fancd2 mutant cells [44].

Some of the above conflicting findings may be reconciled by considering limitations of experimental design. A shortcoming of most studies is the failure to determine the distribution (or even the mean) of foci per cell. This consideration might explain why the MMC-induced Rad51 foci response appeared normal in FA-C cells in one laboratory [211] but not another that measured the foci distribution [128]. The expectation according to our previous work [42,91,149] and the model in Fig. 1 (Section 9) is that MMC-induced Rad51 foci will be attenuated in most or all FA complementation groups in accord with a reduced efficiency of HRR. In fact a reduction in Rad51 and BRCA2 foci induced by MMC was reported for mouse fanca knockout cells based on scoring percentage of cells having more than four foci [124]. Information on the kinetics of focus formation and disappearance should also be revealing but is not yet well reported.

A second limitation is that IR is not an appropriate agent to test for an HRR defect in most FA mutants because most FANC proteins act in the context of stalled/blocked replication forks in damaged DNA rather than directly induced DSBs. Rad51 focus formation after IR exposure partially or exclusively reflects HRR events occurring between sister chromatids rather than at broken replication forks. Rad51 foci form efficiently in G2 cells in response to IR [215].

In the isogenic fancg CHO system, Rad51 foci induction by IR was normal as expected, but in synchronized S-phase cells, the level of spontaneous foci per cell was ~2-fold higher in the fancg cells than the parental control [66]. We interpret this elevation as reflecting a larger number of broken replication forks requiring HRR in fancg cells since a reduced efficiency of TLS (Fig. 2, discussed below) is expected to result in more broken forks. However, in keeping with a reduced efficiency of HRR in fancg cells based on mutation analysis [42], we infer that the observed increased number of Rad51 foci may not reflect bona fide repair.

8.2 Dynamics of FANCD2 focus formation and relationship to BRCA2 and Rad51 foci

The initial discovery of FANCD2 nuclear foci showed that they form only in cells in which FANCD2 is monoubiquitinated [18], and substantial co-localization of FANCD2 with Rad51 is observed [216,217]. FANCD2 foci are assumed to reflect the sites on DNA at which replication fork progression has stalled. FANCD2 foci are produced by diverse kinds of DNA damages and replication inhibitors (MMC, γ-rays, UV-C, hydroxyurea), and the FANCD2K561R mutant protein, which is not ubiquitinated, does not form foci [18,217]. FANCD2 foci do not form in mutants that are deficient in: (a) the FANC core complex [17,18,188,218]; (b) FANCD2’s partner protein, FANCI [19]; (c) Hes1, a core-complex-interacting protein involved in stem cell function and developmental processes [219]; (d) ATR kinase [190,220] (one conflicting report notwithstanding [183]); or (e) the ATR-interacting checkpoint protein HCLK2 [190].

Efficient FANCD2 focus formation also requires γH2AX focus formation [221], an intact BRCA1 protein [18], and normal proteosome function [222]. FANCD2 and BRCA1 foci co-localize, suggesting that the physical interaction observed by immunoprecipitation is functionally important [18]. There is no disagreement concerning the ability of rad51 or brca2 mutant cells to form FANCD2 foci at normal, or nearly normal, efficiency in response to IR and MMC damage [44,126,213,217]. Other proteins shown to co-localize with FANCD2 in response to DNA damage include its interacting partner FANCI [19], core complex proteins (e.g. FANCE [188]), and the ATR kinase [183]. SiRNA-mediated depletion of ERCC1 in human fibroblasts was reported to eliminate focus formation of FANCD2 and reduce its monoubiquitination in response to crosslinking damage [223], but this finding is discordant with studies of ercc1 and xpf human and rodent cell mutants, which showed reduced FANCD2 focus formation and normal monoubiquitination (L. Niedernhofer and P. McHugh, personal comm.)

The independence of FANCD2 and Rad51 with respect to focus formation led to the following conclusion [126]: “On the basis of these data we propose a model in which FANCD2 mediates repair of IR-induced and other DNA damage through a pathway that is independent of the Rad51 homologous recombination repair pathway”. On the contrary, our view [42,91], which is supported by epistasis analysis [68,72] and further detailed in Section 9, is that ubiquitinated FANCD2 promotes Rad51-dependent HRR and thereby determines the efficiency at which HRR occurs. We emphasize again that the formation of Rad51 foci per se does not imply that HRR occurs since focus formation can reflect the early steps of Rad51 recruitment and filament formation.

FANCD2 focus formation may be necessary for efficient recruitment of repair and checkpoint proteins, but conditions were identified under which resistance to ICL damage was seen without focus formation in the DT40 system [224]. A FANCD2(KR)-ubiquitin fusion protein that complemented efficiently, though not completely, did not produce foci upon MMC treatment.

In summary, nuclear foci studies have often been confusing and contradictory, but they can be informative when done with experimental precision, which includes obtaining the distribution of foci per cell. Caveats of these studies include the choice of DNA-damaging agent, the way in which foci are enumerated, and attempts to infer function based solely on the presence or absence of foci such as Rad51.

9. Molecular models

In this section we have attempted to integrate the information discussed above into working models of how the FANC protein network maintains chromosomal continuity when DNA replication is inhibited or faced with virtually any kind of damage or structural impediment. Our view is that these proteins act within a highly coordinated network to initiate the obligatory steps of TLS and HRR during ICL repair (Fig. 1). Moreover, FANC proteins promote these two processes independently under conditions of replication stress to bypass damaged bases or structural barriers and to restore broken replication forks, respectively (Fig. 2).

9.1 Crosslink repair: Coordination of S-phase checkpoint, TLS, and HRR

Here we extend and refine our previous models [42,91,225], as well as those of others [5,226,227], describing how the FANC proteins promote ICL repair, including implementation of an ATR-dependent replication checkpoint specific for crosslink damage [179,180,183]. An ICL represents a formidable block to the DNA replication machinery and is unique in requiring both TLS and HRR for its efficient repair. The FANCM-FAAP24 heterodimer is the only core subcomplex-associated factor known to have DNA binding activity [11,27], which is independent of ATP [13]. FANCM-FAAP24 belongs to the XPF-ERCC1/Mus81-EME1 family of nucleases [228], in which one subunit has catalytic activity, and FANCM possesses both N-terminal helicase-ATPase motifs and a degenerate C-terminal endonuclease domain [11,27,228]. FANCM binds tightly to DNA structures that mimic replication forks and Holliday junctions and promotes their “branch point translocation” [12,13,27], as distinguished from branch migration occurring during HRR [13]. Moreover, FANCM can perform reversal of model replication forks [229], making FANCM-FAAP24 a strong candidate damage-recognition factor that senses DNA replication forks blocked at crosslinks. Thus, this complex may remodel the crosslink-blocked replication intermediate through fork reversal to allow access of checkpoint and repair proteins [12,13,189] and create a substrate that is recognized by Mus81-Eme1 nuclease. This reversed-fork structure, which arises through what was originally termed “branch migration” in a model for replication repair in mammalian cells in 1976 [230], is often referred to as a “chickenfoot.” FANCM-FAAP24 could work in concert with the BLM protein, which is associated with core-complex proteins [231] and is also capable of producing fork regression, creating a 4-way junction [232] (Fig. 1.2). Because the ATP-dependent branch-point translocation activity of FANCM is required for cellular resistance to crosslinking damage but is unnecessary for FANCD2-FANCI monoubiquitination [13,189], one can infer FANCM has at least two distinct functions as discussed above in Section 7.2. FANCM is constitutively associated with chromatin, independent of exposure to MMC or hydroxyurea [14]. FANCM-depleted cells appear to have an intact FA core subcomplex but are defective in its chromatin localization [14].

Activation of the ATR kinase precedes monoubiquitination of FANCI-FANCD2 [220], leading to phosphorylation of many proteins including the FANCD2-FANCI complex itself [19,183], BRCA1 [233], Chk1 [183], FANCG [214], and the MRN complex [183] (see Fig. 1.2). Phosphorylation at six clustered sites on FANCI is necessary and sufficient for resistance to crosslinking damage [48,234], but the importance of FANCD2 phosphorylation is in dispute [48,193]. FANCM-FAAP24 may recruit the other members of the core subcomplex into chromatin [14,224], along with functionally related Hes1 [219], resulting in activation of the FANCL ubiquitin ligase [15] and conjugation of ubiquitin to FANCD2-FANCI Fig. 1.3). Certain phosphorylation events, e.g. Nbs1, and the ICL checkpoint require Snm1B [187].

An elegant series of experiments in the avian DT40 system has shown that the FA inactive core subcomplex has additional functions in ICL repair besides the monoubiquitination of FANCD2-FANCI [48,224]. Core subcomplex proteins (i.e. FANCC,G,L) are necessary both for targeting of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 to chromatin and for a repair function that helps confer MMC resistance [224], such as ATP-dependent processing activities of FANCM that initiate ICL removal [13,189].

Replication fork collapse at a crosslink, measured under conditions of chronic exposure to MMC, is an enzymatically-mediated process requiring Mus81-Eme1 [235] and Snm1B [187]. (Note that this Mus81 dependence of DSB induction was not seen for short 1–3 hr exposures [235,236]). Snm1B was found to interact (indirectly) with FANCD2 and directly with Mus81-Eme1 and the MRN complex [187], which interacts constitutively with FANCD2 [184] (Fig. 1.4). Biochemical and genetic evidence indicates that Mus81-Eme1 plays a major, but not exclusive role, in cleaving the parental strand on the 3′ side of the ICL to produce a one-ended DSB [235]. Mus81 null cells are moderately sensitive to killing by MMC (3-5-fold) [235,237], and eme1 null cells are only modestly sensitive [238] whereas ercc1 null cells are exquisitely sensitive (~50-fold) [235]. The extraordinarily high sensitivity of ercc1 and ercc4/xpf rodent mutants to killing by MMC and other crosslinking agents [239,240], combined with the ability of the XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease to incise crosslinked DNA in the form of Y-shaped structures [241], implicates the XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease in the incision step on the 5′ side of the ICL (Fig. 1.5). We note that a recent, very different model [242] invokes XPF-ERCC1 at a late step in HRR, and not in ICL unhooking. However, a need for XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease activity in the HRR step of ICL repair is not apparent as it is in the case of gene targeting [243].

The role of FANCJ/BRIP1 helicase [96,244] in ICL repair has not been established, and one possibility is that it assists in removing the ICL-containing oligonucleotide. If FANCJ acts at a late step in HRR as suggested [25], fancj cells could be expected, like rad54 cells [245], to be noticeably sensitive to killing by IR and MMS, but they are not [125]. The function of FANCJ in ICL repair was recently reported to require an interaction with the mismatch repair protein MutL [246], which together with Pms2 forms the MutLα complex [247]. However, these results seem to conflict with studies from another laboratory that implicated only the MutSβ (Msh2-Msh3) complex in ICL repair in plasmid-based assays [107,108]. Further evidence for the involvement of MutSβ comes from the findings of a physical interaction between ERCC1 and Msh2 with an epistatic relationship between them [248]. Parenthetically, we note that one study concluded that FANCC was not required for either DSB formation or ICL unhooking following MMC treatment, as measured by gel electrophoresis and the comet assay, respectively [128].

The gap resulting from ICL unhooking is filled by TLS polymerases Pol ζ (Rev3-Rev7 subunits) and Rev1 (part of the Rev3-Rev7 complex [249]), likely producing a base substitution mutation (Fig. 1.6). The finding that depletion of Rev1 in human fibroblasts results in high sensitivity to MMC-induced chromosomal aberrations [51] supports the involvement of Rev1 in the TLS step. In the avian DT40 system rev1, rev3, and rev7 mutants are extremely sensitive to cisplatin [72,73,250], more so than fancc cells [72,73]. Epistasis analysis of double mutants (rev1/fancc and rev3/fancc) showed that they have the same cisplatin sensitivity as rev1 and rev3 single mutants [72,73]. These results of differential sensitivity imply that some ICL repair occurs in the absence of FANCC.

Epistasis studies in the DT40 system have also indicated that FANCC and FANCG have overlapping roles with Rad51 paralogs in repairing ICLs [68,72,214]. HRR of a one-ended DSB is initiated by resection, producing a 3′ end of single-stranded DNA that is converted into a Rad51 nucleoprotein filament (Fig. 1.7) capable of catalyzing strand exchange with the intact duplex DNA (Fig. 1.8), creating a D-loop structure (Fig. 1.9). The polymerase performing HRR synthesis has not been identified, but recent evidence from avian cells suggests that the HRR utilizes low-fidelity TLS polymerases [251,252]. Resolution of the exchange intermediate and re-establishment of the replication fork (Fig. 1.10–1.12) are further detailed in the legend.

9.2 Core complex promotion of TLS and contribution of FANCJ to overcoming blockage

Fig. 2 depicts contributions of FANC proteins to TLS and HRR. In addition, the FANCM-FAAP24 heterodimer contributes to a replication checkpoint in response to conditions (UV-C and hydroxyurea) that elicit TLS and HRR, respectively [189]. See Fig. 1 for ATR and other checkpoint components.

TLS, one way in which cells cope with a wide variety of DNA lesions during a normal S phase [253], occurs at damaged bases and abasic sites (Fig. 2A1). The mutagenesis studies discussed in Section 6 provided strong genetic evidence that FANC core-complex proteins are needed for efficient base substitution mutagenesis produced by TLS polymerases. These experiments were based on fanca, fancb, and fancg mutants. Since human fancd2 fibroblasts and human fibroblasts treated with FANCI siRNA showed normal spontaneous and UV-C induced mutation frequencies in the SupF shuttle vector assay [51], one infers that an intact core subcomplex, but not FANCD2-FANCI monoubiquitination is required for efficient TLS (Fig. 2A.2). These findings highlight the concept of multiple functions of the core subcomplex discussed earlier.

FANCJ/BRIP1 helicase activity is manifest in S phase and is required for normal S phase progression, suggesting that FANCJ removes structural barriers to replication [254] (Fig. 2A.3) such as guanine quadruplexes [96]. In CHO cells, FANCJ shows both S-phase dependent expression and UV-C inducibility [255,256]. Importantly, in both human cells and in C. elegans the phenotype of fancj mutants is excessive deletions in chromosomal regions containing DNA sequences that match the G4 signature motif [95,99,257]. The interaction of FANCJ with BRCA1 is essential for normal progression through S phase, as inferred from the phenotype of an interaction-defective FANCJ mutant [254]. In summary, the FANC core subcomplex proteins, together with FANCJ, promote efficient TLS and replication past structural barriers, thereby maintaining chromosome continuity and cell viability (reproductive capacity).

9.3 FANC protein facilitation of HRR at broken replication forks

There is accumulating evidence that FANC proteins generally promote HRR at broken replication forks in response to various types of replication stress. Importantly, in the absence of a DNA-damaging agent, monoubiquitinated FANCD2 partially colocalizes with BRCA1 and Rad51 in nuclear foci during S phase in (aneuploid) human cells [216,217], strongly suggesting that FANCD2 promotes repair of broken replication forks by HRR. Thus, the FANC protein network is critical for maintaining chromosomal continuity in the face of spontaneous oxidative damage and other lesions that lead to replication fork breaks (Fig. 2B).

Several studies provide evidence that FANC proteins participate in the response to replication stress produced by aphidicolin (which inhibits replicative polymerases) and hydroxyurea, which inhibits ribonucleotide reductase leading to depletion of dNTP pools and causes Mus81-Eme1-mediated broken replication forks upon prolonged exposure [258]. Both drugs efficiently elicit FANCD2 monoubiquitination and focus formation [217,220,259] with substantial co-localization of Rad51 [217]. In fancd2 and core complex mutants aphidicolin exposure causes increased levels of chromosomal breaks and gaps, including increased breakage at classical fragile sites [259]. In human Nalm-6 lymphoblasts, a fancb null mutant was ~2-fold sensitive to killing by hydroxyurea, compared with >10-fold sensitivity to MMC [69] whereas the fancg null CHO mutant was only slightly sensitive to hydroxyurea (1.2-fold compared to 3-fold for MMC) [66].

Genetic evidence for the promotion of HRR by FANC core complex proteins in response to spontaneous DNA damage comes from the HPRT mutation rate and spectrum obtained with the fancg CHO cells and their control lines (Section 6). The simplest lesion that can give rise to a broken replication fork is a nick or gap (or the resulting repair intermediate), which might result in “run-off” of the replication machinery from the DNA template. This class of lesion appears to be relatively frequent during replication since HRR-defective cells are exquisitely sensitive (100- to 1000-fold) to killing by inhibitors of PARP1 [260,261], a sensor of single-strand breaks and major participant in their repair [262,263]. The FANC proteins are also implicated in dealing with this simple class of damage. Mouse fanca, fancc, and fancd2 embryonic fibroblasts, compared to wild type, showed pronounced sensitivity (5- to 20-fold) to killing by two PARP1 inhibitors [264]. (We note that these mutants showed normal induction of Rad51 foci in response to PARP1 inhibition, leading the authors to conclude that “the Fanconi anemia genes are either downstream of RAD51 focus formation or they act in another parallel pathway.” We discussed earlier in Section 8.2 why this interpretation appears incongruent with our model in Fig. 2A.) There are also observations of inhibitor sensitivity in virally immortalized isogenic human fanca, fancd2, and fancg fibroblasts [265,266]. In contrast to the above data, human RKO adenocarcinoma fancc and fancg knockout mutants did not show increased sensitivity to another PARP1 inhibitor, NU1025 [267], which is known to sensitize brca2 mutant cells [261]. Moreover, fancg knockout CHO cells [66] treated with the PARP1 inhibitor KU0058684 showed no enhanced cytotoxicity whereas rad51d HRR-defective CHO cells tested in parallel were 100-fold more sensitive than gene-complemented control cells (J. Hinz, unpublished results). Further studies with diploid human cells are clearly needed to extend the inhibitor studies and to define the overall role of FANC proteins in restoring broken forks by HRR.

10. Future directions

10.1 Need for isogenic diploid cell lines

Many studies have emphasized the normal population variability that is present for endpoints pertaining to DNA repair and other damage responses. We advocate that studies of FANC protein function should be conducted with isogenic cell lines prepared by correcting FA cells with the human gene or cDNA. Correction using cDNAs is less than optimal because many expression plasmids and retroviruses may result in an abnormal level of expression that produces untoward effects. It seems likely that many of the differences reported and reviewed herein between FA mutant versus normal cells, and between different FA mutants, are not exclusively/primarily a consequence of the specific FANC mutations.

Similarly, virus immortalized normal and FA cell lines that deviate from a normal diploid karyotype should be avoided in favor of hTERT-immortalized fibroblasts and EBV-transformed lymphoblasts that are karyotypically normal. Much FA-related research has used model systems of human, rodent, and avian origin in which Tp53 function is defective, an abnormality that may influence experimental outcomes. This limitation can be avoided in immortalized diploid human cell lines. Such isogenic mutant and control cell lines are needed to further test the validity of the models in Figs. 1 & 2. In particular, the quantitative influence of FANC proteins on spontaneous mutagenesis should be determined in fluctuation experiments using chromosomal loci such as HPRT and ATP1A1 loci that efficiently or specifically detect base substitution mutations. Likewise, prototypical DNA-damaging agents that are potent inducers of base substitution mutations, such as ethylnitrosourea and UV-C, can establish the degree to which FANC proteins are required for TLS.

10.2 Limitations of using synthetic repair substrates