Abstract

We report a 13-year-old soccer player with osteonecrosis of the talus and a large carticular fragment. The defect was revitalized with curettage and drilling and filled with autologous bone graft followed by the fixation of the carticular fragment with two conventional lag screws. Screw placement was such that they could be removed arthroscopically. Healing was uneventful. Eighteen months postoperative hardware was indeed removed arthroscopically. He returned to his former competitive level without restrictions or complaints.

Keywords: Ankle, Arthroscopy, Osteonecrosis, Fragment fixation

Introduction

Osteochondral defects (OCDs) of the talus typically occur in young healthy active patients as an isolated lesion and is often associated with previous trauma [3, 14]. In addition to traumatic injury various etiologies, including embolic, hereditary, endocrine, developmental and idiopathic factors have been described [2, 4]. The latter lesions are referred to as osteochondritis dissecans (OD), and occur more often in younger patients [18]. Subchondral osteonecrosis may be present within the talus and this has been associated with sclerosis, deformity and in severe cases articular collapse and bone fragmentation [12].

Current treatment options include open or arthroscopic excision of the separated fragment followed by curettage and bone marrow stimulation of the defect [7, 15, 17]. Fixation of large necrotic fragments has been described for OD of the knee [10, 11]. For the ankle, however, reports in the literature are limited to the treatment of small talar osteochondral lesions using osteochondral grafting with or without fixation of the small separated fragment [1, 5, 8, 9, 13, 15]. We report a 13-year-old soccer player with osteonecrosis of more than 50% of the weight-bearing talar surface. This case provides an opportunity to discuss technical issues that might contribute to our understanding of this type of injury and its healing.

The purpose of this case report is to (1) describe not previously published results of fixation of a large necrotic talar fragment, (2) to discuss the use of conventional lag screws as opposed to the more commonly used Herbert screws for fixation of an OCD in the knee and ankle and (3) introduce a new concept for screw placement to allow for arthroscopic hardware removal with minimal iatrogenic damage to the surrounding cartilage.

Case report

A 13-year-old patient had deep ankle pain since 18 months and gradually increased swelling of his left ankle. His complaints were not precipitated by trauma. He was a very active soccer player. On examination, there was no swelling. The patient did not complain of locking or impingement. He had painful range of motion. Dorsiflexion of his left ankle was slightly impaired with 15° compared with 20° on the healthy side. Plantar flexion was unlimited. The anterior drawer test was negative. There was no pain on palpation. Neurologic and vascular examination was normal. On plain radiographs, a radiolucent area in the anterolateral part of the talus was seen. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a radiolucent multi-loculated defect on the central and lateral aspect of the talus with a large necrotic fragment and coexistent tarsal coalition (Fig. 1). Three-dimensional CT reconstructions showed an overlying fragment involving the entire lateral articular surface of the talar dome, extending medially to about 50% of total talar width (Fig. 2).

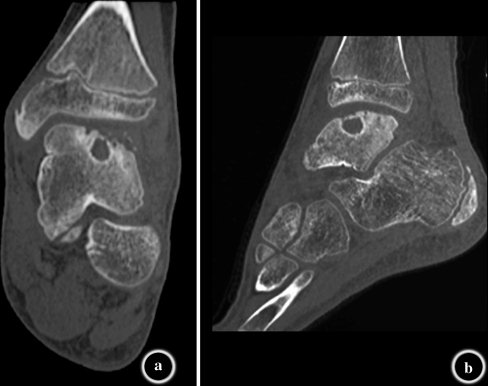

Fig. 1.

a, b Computed tomography show a radiolucent multi-loculated defect on the central and lateral aspect of the talus with a large necrotic fragment

Fig. 2.

3D CT reconstructions show an overlying fragment involving the entire lateral articular surface of the talar dome, extending medially to about 50% of total talar width

The lesion was approached via anterolateral arthrotomy with the patient in lateral decubitus under general anesthesia. The anterior fibulotalar ligament (ATFL) was detached from the fibula. The talar fragment could be identified with ankle plantar flexion and anterior subluxation of the talus. Clinically, the extent of the defect was identical to the radiological findings. The cartilage covering of the defect was intact. The anterior margin of the fragment could be determined by probing the cartilage with a hook. The anterior margin was cut to explore the undersurface of the necrotic fragment. The fragment was lifted using the intact posterior cartilage as a hinge. After curetting and microfracturing of the talus and the undersurface of the necrotic bony fragment, the cysts and bone bed were filled with spongious bone harvested from the distal tibia. Following repositioning of the fragment, it was checked whether sufficient cancellous bone graft was applied to obtain a perfect fit. The fragment was fixed with two 2.7 mm lag screws (24 mm). The screws were positioned in such a way that they could be removed through a routine anterolateral portal with the talus in forced plantar flexion later on (Fig. 3). Re-fixing the ATFL was performed by means of transosseous sutures. The patient was immobilized in a cast for 12 weeks. Immunohistopathology of the lesion obtained intraoperatively showed fragmented necrotic osteochondral bone and reactive hyaline cartilage proliferation as commonly seen in OCDs.

Fig. 3.

Stable fixation was achieved with two 2.7 mm conventional lag screws (24 mm) on the lateral ridge of the talar fragment in a medio-caudal direction to allow for arthroscopic hardware removal

After 18 months, the index surgery postoperative radiographs show complete healing and revascularization of the fragment. The patient was planned for hardware removal by means of a standard anterior ankle arthroscopic procedure [16]. The hyaline cartilage covering the former lesion had completely remained intact and was congruent with the surrounding talar cartilage. The screws could easily be removed (Fig. 4a–f). Postoperatively, the patient was allowed full mobilization. Postoperative radiographs showed complete healing of the fragment (Fig. 5). Two years after the index surgery, the AOFAS ankle score [6] was 90 points out of 100, with some mild residual pain after a day of heavy work on his secondary job in a large garden center. The patient had no functional limitations. He returned to his former competitive level without restrictions or complaints.

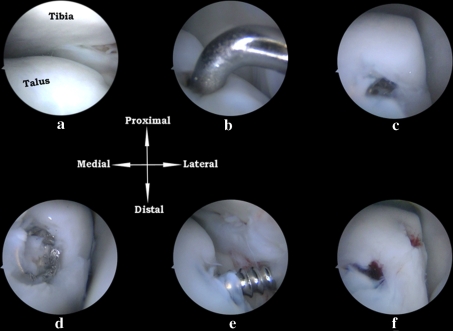

Fig. 4.

The talar dome was identified and radiographic alignment of the fragment was arthroscopically confirmed. Hyaline cartilage had completely regenerated over the fixed fragment (a). Hardware was removed through the lateral portal after careful identification of the screwheads with a probe (b–e). There was no iatrogenic damage to the regenerated cartilage in between the screw defects (f)

Fig. 5.

a, b Postoperative radiographs show reduction of the fragment

Discussion

We report a patient with a large osteochondral lesion on the lateral aspect of the talar dome with a carticular necrotic fragment involving more than 50% of the total talar articular surface. Systematic reviews of treatment strategies for OCDs of the talar dome not exceeding 15 mm reveal that excision, curettage and bone marrow stimulation for OCDs is the treatment of choice [15, 17]. In case of large osteochondral lesions exceeding 15 mm, fixation must be considered [18].

Although excision, curettage and bone marrow stimulation is the treatment of choice for most osteochondral lesions, every case has to be evaluated individually. In the case presented here, there was a partial osteonecrosis of the talus. Conservative treatment would probably have led to the collapse of the talus resulting in deformation. Therefore, this young patient was treated by means of open anatomical reduction and fixation of the large fragment. Rigid fixation with two screws provided the necessary stability to result in union and revascularization of the articular fragment from underneath.

Advantages of this direct open approach are (1) restoring the contour of the talus by adding bone graft after removing the fibrotic layer and necrotic tissue; (2) creating multiple perforations into the talar ‘bone bed’ under direct vision thus making it possible to apply these openings into the bone marrow along the margins as well as in the center of the ‘bone bed’; and (3) direct bone healing is only possible in case of absolute stability obtained by compression. In case of a thin carticular fragment like in our patient, this can best be achieved by applying the screws from above. The screw head finds fulcrum on the thin hard subchondral bone plate and is thus able to exert its function as a proper lag screw.

A technical issue of this case is the use of conventional lag screws as an alternative for Herbert screws to fix the fragment. We feel that conventional lag screws provide a more stable fixation. In case of a conventional lag screw, the surgeon himself controls the amount of compression as opposed to the compressive biomechanical properties of the Herbert screw itself that are limited by its design. In addition, we would like to emphasize the direction of placement of the screws in order to facilitate subsequent arthroscopic removal aiming for minimal iatrogenic damage to the residual and regenerated viable cartilage. Two 24 mm 2.7 mm lag screws were placed with their heads on the lateral edge of the talar dome just frontal to the distal fibula in a medio-caudal direction in a way that they could be removed through a standard anterolateral portal in a subsequent procedure.

Conclusion

This case illustrates that viable hyaline cartilage regeneration can be anticipated, even after the reduction of a necrotic fragment that involves the entire lateral articular surface of the talar dome and extends medially to about 50% of total talar width. Technical notes involve the use of conventional lag screws in a fashion that facilitates arthroscopic hardware removal to avoid iatrogenic damage with this minimally invasive technique.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Baltzer AW, Arnold JP (2005) Bone–cartilage transplantation from the ipsilateral knee for chondral lesions of the talus. Arthroscopy 21:159–166. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2004.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Berndt AL, Harty M (1959) Transchondral fractures (osteochondritis dissecans) of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 41-A:988–1020 [PubMed]

- 3.Canale ST, Belding RH (1980) Osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 62:97–102 [PubMed]

- 4.Davidson AM, Steele HD, MacKenzie DA et al (1967) A review of twenty-one cases of transchondral fracture of the talus. J Trauma 7:378–415 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gautier E, Kolker D, Jakob RP (2002) Treatment of cartilage defects of the talus by autologous osteochondral grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84:237–244. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.84B2.11735 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelaar RS et al (1994) Clinical rating systems for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot, hallux and lesser toes. Foot Ankle 15:349–353 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kumai T, Takakura Y, Higashiyama I et al (1999) Arthroscopic drilling for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:1229–1235 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kumai T, Takakura Y, Kitada C et al (2002) Fixation of osteochondral lesions of the talus using cortical bone pegs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84:369–374. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.84B3.12373 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lee CH, Chao KH, Huang GS et al (2003) Osteochondral autografts for osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. Foot Ankle Int 24:815–822 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Miniaci A, Martineau PA (2007) Technical aspects of osteochondral autograft transplantation. Instr Course Lect 56:447–455 [PubMed]

- 11.Miura K, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E et al (2007) Results of arthroscopic fixation of osteochondritis dissecans lesion of the knee with cylindrical autogenous osteochondral plugs. Am J Sports Med 35:216–222. doi:10.1177/0363546506294360 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pearce DH, Mongiardi CN, Fornasier VL et al (2005) Avascular necrosis of the talus: a pictorial essay. Radiographics 25:399–410. doi:10.1148/rg.252045709 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Sammarco GJ, Makwana NK (2002) Treatment of talar osteochondral lesions using local osteochondral graft. Foot Ankle Int 23:693–698 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schuman L, Struijs PA, van Dijk CN (2002) Arthroscopic treatment for osteochondral defects of the talus: results at follow-up at 2 to 11 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84:364–368. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.84B3.11723 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Tol JL, Struijs PA, Bossuyt PM et al (2000) Treatment strategies in osteochondral defects of the talar dome: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Int 21:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.van Dijk CN, Scholte D (1997) Arthroscopy of the ankle joint. Arthroscopy 13:90–96. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(97)90215-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Verhagen RA, Struijs PA, Bossuyt PM et al (2003) Systematic review of treatment strategies for osteochondral defects of the talar dome. Foot Ankle Clin 8:233–242. doi:10.1016/S1083-7515(02)00064-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Zengerink M, Szerb I, Hangody L et al (2006) Current concepts: treatment of osteochondral ankle defects. Foot Ankle Clin 11:331–359. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed]