Abstract

In the past decade, colleges and universities have seen a large increase in the number of students referred for the violation of alcohol policies. Stepped care assigns individuals to different levels of care according to treatment response, thereby maximizing efficiency. This pilot study implemented stepped care with students mandated to attend an alcohol program at a private northeastern university. High retention rates and participant satisfaction ratings suggest the promise of implementing stepped care with this population. Considerations for future applications of stepped care with mandated students are discussed.

Over the past decade, the number of college students required to attend mandated alcohol programs on their campuses nearly doubled, rising from 1.8% in 1993 to 3.5% in 2001.1 The events that result in mandated referrals range in severity from being in the presence of alcohol to requiring hospitalization for alcohol-related injury or intoxication.2 A variety of responses and interventions have been implemented with this population, including fines, computerized courses, and in-person interventions. Counseling sessions vary in type and intensity from individual session to multi-session groups.3 Given the identified variability in severity levels and the finding that many mandated students reduce their alcohol use without an intervention,4 it is possible that not all students require a clinical intervention of equal level and intensity.

Stepped care has been used with individuals exhibiting different levels of risk and treatment response. Stepped care is a dynamic, performance-based procedure in which individuals not responding to an initial level of treatment that is the least intensive are then provided a more intensive treatment.5,6 Within this framework, different levels of interventions are linked together, with clinical guidelines used to determine referrals to higher levels of care.

A stepped care approach is commonly used in clinical settings, and research has evaluated its efficacy to address a wide range of problems ranging from conduct disorder7 to bulimia.8 To date, however, only two published studies have implemented stepped care to reduce alcohol use. Breslin 9 empirically evaluated heavy drinking adults receiving standard alcohol treatment (four weekly hour-long sessions and two aftercare phone calls). Individuals who reported drinking 12 or more drinks per week during the first three weeks of treatment were identified as non-responders. Non-responders were randomized to receive (a) no additional treatment or (b) supplemental treatment, which consisted of additional readings, written exercises, and an additional 60-minute session intended to increase motivation to change. There were reductions in days abstinent and drinks per drinking day in both groups at six-month follow-up but no group differences. The authors hypothesized that the supplemental intervention was not intensive enough to facilitate greater change in this group; specifically, non-responders had already received a lengthy assessment and three hour-long sessions addressing their drinking. The second study, though not initially designed to evaluate stepped care specifically, did use a stepped care approach in one of the intervention conditions. In this study, Marlatt10 provided a brief motivational intervention (BMI) to incoming college students exhibiting risky alcohol use. One year later, students who continued to drink at risky levels (n=56) were contacted by phone and offered encouragement and assistance in reducing their alcohol use, and interested students received an additional intervention (n=34; 61%). Although the efficacy of these supplemental sessions was not evaluated, the willingness of the students to receive a subsequent intervention provides support for the potential feasibility of stepped care with college students.

This pilot study implemented stepped care with mandated college students. In accordance with the stepped care approach, the first step of should be the least intensive yet still likely to work.6 Minimal interventions, defined as the least intense activity that can have a therapeutic or preventative influence,11 are typically 5 to 15 minutes long and have resulted in significant reductions in alcohol use among adults.12,13 Although a minimal intervention has yet to be empirically evaluated with mandated students, its brevity and success with adults made it an appropriate first step intervention.

The second step intervention, reserved for those students who do not respond to a minimal intervention, should by nature be more intensive. Brief motivational interventions (BMIs) have been implemented successfully with mandated students.2,3,14 BMIs for college students typically incorporate motivational interviewing15 and consist of one to two sessions, each ranging from 30–60 minutes. Motivational interviewing (MI) is a directive, client-centered counseling style that facilitates motivation for change by encouraging individuals to explore and resolve their ambivalence about their current behaviors. Mandated students have been very receptive to BMIs in previous research, demonstrated by high intervention approval ratings and high ratings of willingness to recommend a similar session to a friend who is experiencing alcohol problems.2 In addition, mandated students have reported reductions in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems up to six months following a BMI.2,16

This pilot study was a preliminary evaluation of the feasibility and initial efficacy of a stepped care approach with mandated students. The aims of this study correspond with Stage 1b in the stage model of therapy development. 17 Specifically, we sought to demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of implementing stepped care with two interventions, specify and evaluate our procedures for assigning students to different levels of care, evaluate our ability to recruit sufficient numbers of students, demonstrate the feasibility of our control condition, and calculate effect sizes to inform future research. Due to the small sample sizes involved, Stage 1b research often does not result in adequate statistical power to detect group differences.

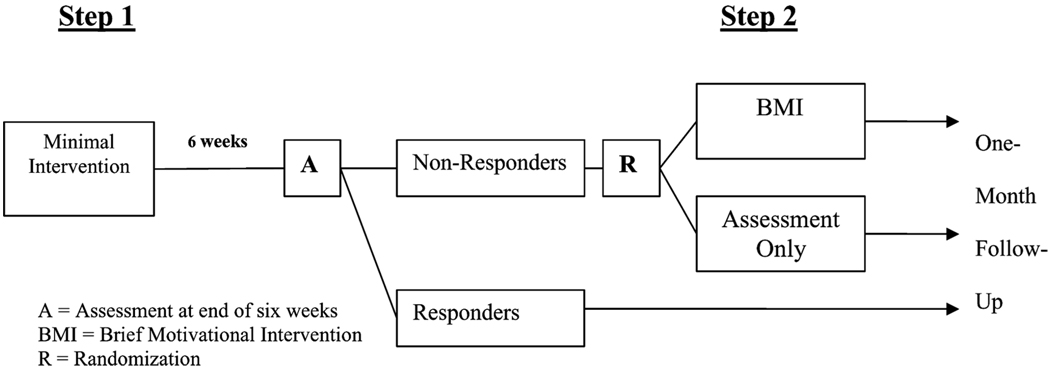

There were two steps of intervention in this project (see Figure 1). All students received Step 1, a baseline assessment and a 15-minute minimal intervention. Four weeks later, all participants were re-assessed using a brief Web-based survey. Students who reported continued risky alcohol use (labeled non-responders) received Step 2, randomization to a 45–60 minute BMI or an assessment control condition. Follow-up assessments at 10 weeks post-baseline (four weeks after stepped-care assignment) allowed comparisons between the three groups (ie, responders, non-responders assigned to receive a BMI, and non-responders assigned to receive assessment only). It was hypothesized that participants who reported low alcohol use at baseline would continue to report low alcohol use throughout the study. Second, it was hypothesized that participants continuing to exhibit risky alcohol use who received a BMI would exhibit greater reductions in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems than participants in an assessment control group. Satisfaction data were collected for both interventions.

FIGURE 1.

Stepped-Care Approach for Mandated College Students

METHOD

Sample and Recruitment

This study was conducted at a private, four-year, northeastern university (3,300 undergraduates; 51% female; 15% minority). All first time alcohol offenders are referred to the university’s Alcohol Incident Referral Program (AIRP) by resident hall advisors or campus security. In the spring semester of 2004–2005, students were given the option to participate in the study or receive treatment as usual from the AIRP, which consisted of a 15–30-minute individual discussion of their referral incident and alcohol use. Forty-three out of 50 students (86%), aged 18 years and older, agreed to participate and provided informed consent. All who refused to participate cited time constraints as their reason (the baseline assessment and intervention took 20–30 minutes longer than treatment as usual). The sample was primarily freshmen (67%) and sophomores (24%), Caucasian (94%), male (67%), and living on campus (95%). Offenses were drunk in public (n=3), being in the presence of alcohol (n=5), possession of alcohol (n=32), taken to the local emergency room for alcohol intoxication (n=2), and vandalism (n=1). Average elapsed time between the infraction and baseline assessment was 21 (±17) days. Participants were paid $ 10 at baseline and $15 for completing each follow-up assessment, for a total of $40. All procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Participants self-administered a baseline assessment including a demographics questionnaire and the Alcohol and Drug Use Measure,2,18 which measures the frequency of binge drinking in the past month (defined as five or more drinks on one occasion for men; four or more drinks on one occasion for women1). Typical Blood Alcohol Level (tBAL) was calculated as follows:

where consumption = number of drinks consumed in a typical drinking session; hours = number of hours over which the drinks were consumed; weight = weight in pounds; and GC = gender constant (9.0 for females and 7.5 for males19). Alcohol-related consequences were assessed by a 20-item version of the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST20). This version of the YAAPST measures a single dimension of alcohol problem severity, reflects a broad range of problems, and has superior distributional properties compared to the original YAAPST.21 It assessed the past year’s frequency of negative consequences of alcohol use at baseline, and during the past month at the 6- and 10-week follow-ups. The Event Description Measure is an open-ended interviewer-administered measure developed for use in BMIs that follow alcohol-related incidents14,22,23 which records the participants’ description of the alcohol-related infraction. Upon completion of both interventions, a seven-item Evaluation Form2,18 was used to evaluate participants’ satisfaction.

Implementation of Stepped Care Approach

To preserve the efficiency of stepped care, it is important to have stringent criteria determining which individuals should receive more intensive treatment. This criterion is established through the use of tailoring variables and decision rules.5,24 Ideally, tailoring variables are objective and identify which individuals would benefit from additional treatment. We employed two tailoring variables consistently associated with risky alcohol use in college students: heavy episodic drinking and scores on the YAAPST-20. Large-scale surveys of drinking- and alcohol-related consequences of mandated students are not available. However, research with non-mandated students indicates that 44% of college students report binge drinking 1–2 times in the past two weeks, an amount associated with increased risk for adverse consequences of drinking.1 In addition, 33% of college students reported five to nine alcohol-related problems over the previous year on the shortened YAAPST, a level that indicates that these students would benefit from brief, tailored intervention such as BMIs.21 Decision rules are highly operationalized and specify which individuals are “stepped up” to receive a more intensive treatment, based on the tailoring variables. After adjusting these two indices of risk to reflect the one-month follow-up period used in this study, we assigned students to Step 2 who reported three or more binge drinking episodes in the past 30 days and/or a cutoff score of two on the shortened YAAPST.

Interventions

Step 1: Minimal Intervention

The manualized minimal intervention was administered by the AIRP peer counselors. In previous research, peers have delivered considerably complex, multi-session BMIs found to be as effective4 or more effective25 than BMIs delivered by professionals. At the beginning of the session, the counselor completed the Event Description Measure to facilitate discussion of the events leading up to the incident, the reactions of friends and family, and any changes that the student had made to his or her drinking as a result. Prompts included asking the participant to describe the day that led up to the event, what and how much he/she drank, what happened during and after drinking, and others involved. The counselor then provided a 12-page booklet containing educational information on what constitutes a standard drink, guidelines for sensible drinking, indicators of risky drinking, information on what to expect should one decide to make a change in drinking, specific behavioral strategies to cut down on drinking, and a list of further resources for change. Throughout the session, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions or discuss their personal alcohol use with the counselor. The minimal intervention took 11 (± 3) minutes.

Trained and supervised interventionists were required to perform three role plays of the minimal interventions before beginning the study. Weekly supervision meetings addressed issues that arose during the course of the study. No participants required referral to more intensive treatment. In addition, all minimal interventions were tape recorded and reviewed to ensure treatment adherence. All sessions were consistent with the manual.

First Follow-Up and Determination of Responder Status

Four weeks after the baseline assessment and minimal intervention, participants (41/43; 95%) completed a follow-up assessment over the internet. Reminder emails that included a link to the Web survey were sent to participants on their due date. Thirty-two participants (78%) met the Step 2 criteria for risky drinking (n=5), YAAPST score (n=2), or both (n=25). Urn randomization,26 using gender and race as blocking variables, was used to randomly assign these participants to the BMI (n=14) or no-assessment control (n=18). Participants assigned to BMI received their intervention within 11 (± 5) days of their assignment.

Step 2: Brief Motivational Intervention

Adapted from previous interventions with college students,27 this BMI has resulted in significant reductions in alcohol use and problems with mandated and non-mandated students.2,18 BMIs were delivered by the first author, who has six years of experience conducting brief interventions with substance abusers. At the beginning of the BMI, the participant was given a personalized report that provided feedback from the participant’s responses to the baseline and six-week follow-up. The participant then engaged in a discussion of topics such as normative quantity/frequency of drinking, blood alcohol content (BAL) and tolerance, alcohol-related consequences, influence of setting on drinking, and alcohol expectancies. The participant was also provided with educational information related to their personal experiences (eg, discussing the relationship between BAL and alcohol-related consequences) and introduced to harm reduction as a way to minimize risky behaviors.28 If the participant was interested in making some changes to his/her drinking, options for change were discussed during the session. Throughout the BMI, the four principles of motivational interviewing were followed: express empathy, develop discrepancy, roll with resistance, and support self-efficacy for change.15 BMIs lasted 55–60 minutes.

Assessment Control

Students in the assessment control condition received only telephone or email reminders to complete follow-up assessments.

Ten-Week Follow-Up

Four weeks after random assignment to condition (10 weeks post-baseline), all participants received reminder emails to complete the follow-up assessment on the web. In all, 41 of the 43 participants (95%) completed this assessment.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

We examined the equivalence of the two groups of non-responders at the six-week assessment, when assignment to the BMI or assessment control conditions occurred (see Table 1). There were no significant differences between these two conditions on demographics or the key baseline variables (p > .10). The two participants who did not complete the six-week follow-up assessment were not significantly different from the other participants in demographics or the four outcome variables. Examination of the distributional properties of variables revealed no outliers greater than three standard deviations from the sample mean, and no variables were significantly skewed or kurtotic.29 A review of judicial records revealed that no participants received a second infraction during the course of the study.

TABLE 1.

Alcohol use and problems for responders (n = 9), non-responders who received a BMI (n = 14), and non-responders who received assessment-only (n = 14)

| Baseline M (SD) | Six-week M (SD) | Ten-week M (SD) | Effect sizes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dWG | dBG | ||||

| Binge drinking episodes | |||||

| Responders | 1.67 (2.50) | 1.00 (0.86) | 2.22 (2.68) | 0.44 | |

| Non-Responders, BMI | 6.67 (3.79) | 6.35 (4.29) | 4.57 (2.14) | 0.52 | 0.08 |

| Non-Responders, assessment | 7.05 (3.17) | 6.55 (2.33) | 5.06 (3.33) | 0.36 | |

| Drinks per week | |||||

| Responders | 10.11 (6.43) | 6.67 (5.93) | 8.56 (6.27) | 0.33 | |

| Non-Responders, BMI | 19.35 (8.34) | 19.5 (11.23) | 17.07 (9.77) | 0.50 | 0.57 |

| Non-Responders, assessment | 21.86 (9.96) | 23.83 (10.69) | 16.50 (9.57) | 0.66 | |

| Typical BAL | |||||

| Responders | 0.065 (.059) | 0.069 (.036) | 0.072 (.054) | 0.05 | |

| Non-Responders, BMI | 0.115 (.051) | 0.110 (.051) | 0.104 (.049) | 0.11 | 0.72 |

| Non-Responders, assessment | 0.115 (.059) | 0.144 (.052) | 0.101 (.067) | 0.78 | |

| YAAPST, 20-item version | Past year | Past month | Past month | ||

| Responders | 16.69 (1.00) | 0.22 (0.44) | 0.55 (0.88) | 0.39 | |

| Non-Responders, BMI | 19.35 (8.34) | 2.93 (1.94) | 1.50 (0.94) | 0.89 | 0.30 |

| Non-Responders, assessment | 15.88 (2.14) | 3.11 (1.91) | 2.22 (1.99) | 0.43 | |

Note. At six-week assessment, students who continued to drink in risky fashion were assigned to BMI or Assessment only.

Abbreviations: BAL = blood alcohol level; YAAPST = Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test; BMI = Brief Motivational Intervention Within-group d calculated from six- to ten-week follow-ups.

Satisfaction Ratings

Both interventions were rated highly (see Table 2). The BMI received significantly higher ratings on the relevance of the provided information and whether the students would recommend a session to other students like themselves (p < .003; Bonferroni correction p = .01).

TABLE 2.

Intervention ratings of step 1 (n = 43) and step 2 (n = 14) interventions

| Item | Step 1 | Step 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you feel that the information provided to you was relevant to you personally? | 2.65 (0.80) | 3.50 (0.76)* |

| 2. Would you recommend a session such as this to other students like yourself? | 2.74 (0.92) | 3.50 (0.58)* |

| 3. If a friend was in need of help with his or her drinking, would you recommend a session such as this? | 3.39 (0.66) | 3.71 (0.61) |

| 4. The session was informative and helped me learn more. | 3.97 (1.16) | 4.35 (1.15) |

| 5. The session influenced my opinion about the topic. | 3.50 (1.41) | 3.85 (1.17) |

| 6. Influenced future drinking behaviors | 3.47 (1.40) | 3.57 (1.09) |

| 7. Met all of my expectations | 4.04 (1.03) | 4.21 (1.12) |

Note. Items 1–3 answered on a four-point Likert scale (1 = no, definitely not; 4 = yes, definitely). Items 4–7 answered on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true; 3 = neither true nor untrue; 5 = extremely true).

Unpaired t-test (df = 55), p < .05.

Outcome Analyses

Responders

To evaluate whether the alcohol use of the nine responders changed over the course of the study, we conducted three repeated-measures ANOVAs. Using a Bonferroni correction of p=.02 to control for Type I error,30 the time effects for all three models were non-significant on binge drinking episodes, F(2,16)=0.95, p=.40; drinks per week, F(2, 16)=1.78, p=.20; and typical BAL, F(2,16)=2.03, p=.16. The recall period for alcohol-related problems was the past month at the six- and ten-week follow-ups; a paired t-test did not indicate a significant change in alcohol-related problems, t (8)=0.8, p=.44.

Non-Responders

We conducted hierarchical regressions to assess treatment response of the non-responders on the four dependent variables: number of binge drinking episodes, drinks per week, typical BAL, and abbreviated YAAPST score. In each analysis, the dependent variable was change in the outcome variable (ie, ten-week follow-up minus six-week follow-up). In the first step, no predictors were included in the regression model (ie, an intercept-only model). In this model, the intercept represents the effect of time, and the results are equivalent to those that would be provided by a paired t-test. In the second step, the six-week scores (centered at 0) were added in order to evaluate time effects, controlling for regression to the mean. In the third step, group differences were evaluated by entering a dummy-coded variable (BMI=0; 0; assessment=1). Using a Bonferroni correction of p=.013 and controlling for regression to the mean, there were no group differences in the four dependent variables (p > .2). However, significant time effects were found for the number of binge drinking episodes, F(2,29)=12.88, p < .001; drinks per week, F(2,29)=7.60, p < .01; and abbreviated YAAPST score, F(2,29)=10.23, p < .001. In exploratory analyses, participant gender and days since infraction failed to predict reductions in use.

Effect Sizes

Consistent with Stage 1b research, we calculated effect sizes for both the responder and non-responder groups following the six-week assessment (see Table 1). As recommended by Cohen,31 effect sizes can be described as small (0–0.30), medium (0.30 to 0.80), or large (greater than 0.80). We calculated between-group (at ten-week follow-up) and within-group (six-week to ten-week follow-up) effect sizes (d). For the responder group, we observed small to medium within-group effect sizes (d from .05 to .44). For the BMI and assessment control, the magnitude of between-group differences was small to medium (d from .08 to .72). Due to the small sample size, only an enormous between-group difference would have been detectable (d=1.06, if power=0.80 at p=.05). Small to medium within-group effect sizes were evident for alcohol use variables, with a large within-group effect for the BMI group on alcohol-related problems (d=.89).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study of stepped care with mandated college students, and it accomplished the goals of Stage 1b pilot research:17 the majority of participants agreed to participate in the project and returned for subsequent interventions. This is especially promising, as one of the most challenging aspects of stepped care is having participants return for more intensive, or “stepped up” interventions. 32 Participants also rated both interventions positively. The project demonstrated the feasibility of an assessment-only control, as no students were referred again following the initial intervention nor refused to complete the scheduled follow-ups. All completed their Internet assessments promptly and did not appear to under-report their alcohol use; that is, participants continued to report risky drinking, which made them eligible for Step 2. There were no group differences detected between the BMI and assessment control conditions, which was not unexpected given the small sample size of a Stage 1b trial. However, small to moderate within-group effect sizes were detected for reductions in drinking- and alcohol-related problems. Perhaps most importantly, students who reported low levels of alcohol use at baseline maintained low-risk drinking throughout the study, highlighting the utility of stepped care with these students. Specifically, providing an intensive alcohol intervention to students consistently reporting low-risk drinking does not appear to be warranted and is likely an inefficient use of program resources.

Although this pilot project demonstrated the feasibility of implementing stepped care with mandated students, students receiving the BMI did not reduce their alcohol use and problems. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, the statistical tests were underpowered and could only have detected between-group differences of a large magnitude. Second, the single-session BMI may not have been intensive enough to reduce risky drinking in mandated college students who have already received a minimal intervention. Perhaps a multi-session intervention may be more effective for this subset of students. 33 Third, the timing of the assessments may have masked the source of the observed reductions in risky drinking. The follow-up for the majority of participants occurred during finals period or in the early summer. Alcohol use by students has been demonstrated to be higher during periods of low academic demand (eg, beginning of the semester) and lower during exam periods;34 thus, reductions observed in the assessment control condition may have been the result of external influences.

The findings of the study suggest that improvements could be made for future implementations of stepped care with mandated students. First, the brief follow-up limited our ability to evaluate the long-term changes in alcohol use and problems. Longer follow-up periods (eg, 3 to 12 months) could better evaluate the impact of the provided intervention(s) on alcohol use and problems. Second, we did not include a control group of mandated students who did not receive any intervention. As a result, we are not able to determine whether the reductions in drinking observed are due to the incident, the process of being referred, repeated assessments, or other factors. Future research could assign students to treatment as usual and a stepped care protocol. Third, future applications of stepped care should involve careful consideration of tailoring variables and decision rules, which specify the student who will receive more intensive treatment. Decision rules cannot be effective unless appropriate and well-measured tailoring variables are assessed.5 Future research may select different tailoring variables (eg, additional referrals) and/or decision rules (eg, five or more heavy drinking episodes in the past month) to identify the students who would most benefit from a subsequent intervention. Finally, all data were collected by participant self-report. Although the use of collateral information has provided little evidence that mandated students systematically under-report their alcohol use on self-report measures,35 it is possible that students may have misrepresented their alcohol use and problems. Therefore, the use of collateral informants may be worthwhile in future research, as demand characteristics may influence self-report (eg, under-reporting use to avoid receiving more intensive treatment).

In sum, the problems associated with alcohol use in college highlight the need for innovative intervention strategies,36 especially when providing care to the increasing numbers of mandated students. The findings of this pilot project indicate the promise of stepped care in helping college alcohol programs determine the most effective allocation of their resources. A considerable proportion of mandated students may not require intensive intervention, permitting alcohol programs to devote more resources to students who continue to exhibit risky drinking. For example, students who are experiencing severe problems from alcohol (eg, dependence) may benefit from more intensive treatments such as detoxification, relapse prevention programs, and/or pharmacoptherapy (eg, naltrexone). Challenges for future implementation of stepped care include the selection of appropriate tailoring variables and decision rules and the identification of interventions of appropriate intensity that will facilitate reductions in alcohol use and problems in this high-risk subgroup of mandated students.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Research Excellence Award from the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, as well as by grant R01-AA015518 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, Md. (Dr. Borsari).

The authors wish to thank the director of the Alcohol Incident Referral Program, Donna Darmody, and her staff, Nicolette Faro, Nicole Guercia, Meaghan Landrigan, and Matthew O’Brien for their support on this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Kuo M. Underage college students’ drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50:223–236. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett NP, Read JP. Mandatory alcohol intervention for alcohol-abusing college students: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004;5:185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Stepped care as a heuristic approach to the treatment of alcohol problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Initial impact of the fast track prevention trial for conduct problems: I. The high-risk sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;7:631–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treasure J, Schmidt U, Troop N, Tiller J, Todd G, Turnbull S. Sequential treatment for bulimia nervosa incorporating a self-care manual. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:94–98. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslin FC, Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, Sdao-Jarvie K, Borsoi D. Problem drinkers: evaluation of a stepped-care approach. J Subst Abuse. 1999;10:217–232. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high risk college student drinkers: results from a two-year follow-up assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babor TF. Avoiding the horrid and beastly sin of drunkenness: does dissuasion make a difference? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:1127–1140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97:279–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilk AI, Jensen NM, Havighurst TC. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials addressing brief interventions in heavy alcohol drinkers. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:274–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012005274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnett NP, Fromme K, O’Leary Tevyaw T, et al. Brief alcohol interventions with mandated or adjudicated students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:966–975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128231.97817.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. Second edition. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tevyaw TO, Borsari B, Colby SM, Monti PM. Peer enhancement of a brief motivational intervention with mandated college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:114–119. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: two computer programs and their application in therapy and research. Addict Behav. 1979;4:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. J Am Coll Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahler CW, Read JP, Strong DR, Palfai TP, Wood MD. Mapping the continuum of alcohol problems in college students: a Rasch model analysis. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:322–333. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett NP, Monti PM, Spirito A, et al. Alcohol use and related harm among older teenagers treated in an emergency room: the importance of alcohol and college status. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:342–349. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:989–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borsari B, O’Leary Tevyaw T. Stepped care: a promising treatment strategy for mandated college students. NASPA Journal. 2005;42:381–397. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, et al. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;12 Suppl.:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students: A Harm Reduction Approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention and treatment. Addict Behav. 2002;27:867–886. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidell LS, Tabachnick BG. Preparatory data analysis. In: Schrinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of Psychology: Research Methods in Psychology. Vol. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grove WM, Andreason NC. Simultaneous tests of many hypotheses in exploratory research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170:3–8. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. Second edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKay JR. Is there a case for extended interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders? Addiction. 2005;100:1594–1610. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller ET, Kilmer JR, Kim EL, Weingardt KR, Marlatt GA. Alcohol skills training for college students. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens through Brief Interventions. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 183–215. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.La Forge R, Borsari B, Baer JS. The utility of collateral informant assessment in college alcohol research: results from a longitudinal prevention trial. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:479–487. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Task Force on College Drinking. Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2001. Use Proven Strategies, Fill Research Gaps. Final report on the panel on contexts and consequences. [Google Scholar]