Abstract

Organocatalytic Mannich addition of aldehydes to a formaldehyde-derived iminium species catalyzed by proline-derived chiral pyrrolidines provides β-amino aldehydes with ≥ 90% ee. Mechanistic analysis of the proline-catalyzed reactions suggests that non-hydrogen-bonded ionic interactions at the Mannich reaction transition state can influence stereochemical outcome. The β-amino aldehydes from our process bear a substituent adjacent to the carbonyl and can be efficiently converted to protected β2-amino acids, which are important building blocks for β-peptide foldamers that display useful biological activities.

The Mannich reaction,1 in which an enol or enolate attacks an imine or an iminium ion, is a powerful tool for introducing aminoalkyl fragments into organic molecules. Imines derived from aryl aldehydes have been common substrates in recent efforts to develop asymmetric organocatalytic versions of this reaction; these substrates necessarily provide Mannich adducts containing aryl substituents adjacent to nitrogen.2 Our attention was drawn to formaldehyde-derived substrates, because β-amino aldehydes from such substrates can be used to generate β2-amino acids, which are valuable building blocks for β-peptide foldamers and other targets.3 Many routes to enantio-enriched β2-amino acids have been described; most involve chiral auxiliaries, and few are amenable to large-scale synthesis.4 Here we report an enantioselective organocatalytic method for aminomethylation of aldehydes, which leads to a new and efficient synthesis of β2-amino acids (Scheme 1). Our observations provide evidence that non-H-bonded ionic interactions at the Mannich reaction transition state can influence stereochemical outcome.

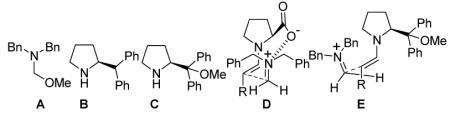

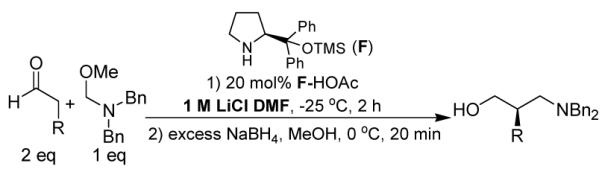

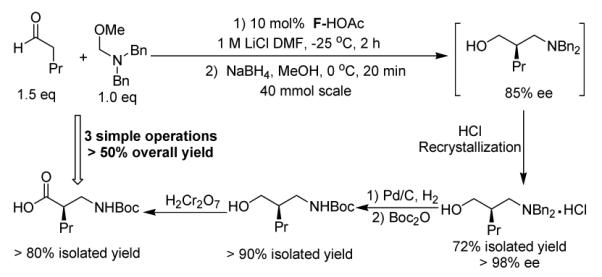

Scheme 1.

Aminomethylation of aldehydes and its application in β2-amino acid synthesis

Formaldehyde does not form stable imines,5 so we examined formaldehyde derivatives such as A that can generate a methylene iminium species in situ.6 We examined L-proline and chiral pyrrolidines as catalysts for nucleophilic activation of aldehyde reactants. The Mannich reaction products, α-substituted β-amino aldehydes, were immediately reduced to the corresponding β-substituted γ-amino alcohols to avoid epimerization. Initial studies involving pentanal revealed modest enantioselectivity when the reaction was carried out with 20 mol % catalyst in DMF at -25 °C for 24 hr. The enantiomeric preference observed with L-proline was opposite that observed with 2-alkyl-pyrrolidines derived from L-proline, such as B or C7 (used with equimolar acetic acid). A comparable switch in product configuration for organocatalytic Mannich reactions involving aryl imines and for α-amination of aldehydes has been observed by Barbas, Jørgensen, List, Córdova and others.2, 11c The commonly accepted rationale for this stereochemical preference switch involves hydrogen bonding:8 the carboxylic acid group of the L-proline-derived enamine is thought to H-bond to the electrophile at the transition state, while the substituent of a 2-alkyl-pyrrolidine sterically repels the electrophile, forcing it to approach the enamine from the opposite face. This hypothesis is reasonable but cannot explain our results with L-proline since our electrophile, an iminium ion, cannot accept a hydrogen bond. We propose instead that approach of the electrophile to the proline-derived enamine is controlled by an electrostatic attraction of iminium to carboxylate (D); the carboxylate is presumably generated by methoxide liberated upon iminium formation. We follow precedent in invoking steric repulsion to rationalize the results with 2-alkyl-pyrrolidines (E).

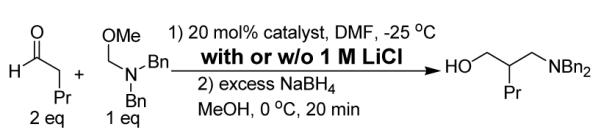

Our hypothesis is consistent with computational results of Houk et al. for Mannich reaction of imines, in which an ionic attraction between protonated imine and carboxylate was proposed.9 We tested our hypothesis by conducting the L-proline-catalyzed reaction in the presence of LiCl. If the putative iminium/carboxylate attraction determines the direction of iminium approach to the enamine, then the ionic additive should diminish enantioselectivity because lithium cation will compete with the iminium for ion pairing, and chloride will compete with the carboxylate. Indeed, the L-proline-catalyzed Mannich reaction showed little or no enantioselectivity in the presence of 1 M LiCl (Table 1), which supports transition state model D. However, 1 M LiCl leads to a moderate but reproducible enantioselectivity enhancement for the reaction catalyzed by 2-alkyl-pyrrolidine C; a similar result was observed for B.10 The origin of this enhancement is unclear.

Table 1.

Salt effect

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entrya | catalyst | salt | time | eeb | favored enantiomerc |

| 1 | L-proline | -- | 24 h | 49 | S |

| 2 | L-proline | LiCl | 24 h | <5 | -- |

| 3 | C-HOAc | -- | 2 h | 67 | R |

| 4 | C-HOAc | LiCl | 2 h | 80 | R |

Yield of all reactions > 80% as measured by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture before reduction; the reduction is quantitative.

Determined by chiral phase HPLC.

See supporting information for stereochemistry determination.

In our initial studies the reaction catalyzed by C gave better enantioselective than that of B. We attribute the improved enantioselectivity of catalyst C relative to B to the increased steric bulk of the 2-substituent in C. Jørgensen et al. Hayashi et al. and Córdova et al. have recently reported nucleophilic activation of aldehydes by F,11 in which the trimethylsilyl group provides a further increase in steric bulk relative to the methyl group in C. We found that F leads to an improvement in enantioselectivity relative to C.10 Table 2 shows that Mannich reactions of five aldehydes proceeded with > 90% ee when catalyzed by 20 mol % F (with 20 mol % acetic acid) in DMF containing 1 M LiCl.

Table 2.

Enantioselective aminomethylation of aldehydes

After column chromatography on silica gel.

Determined by chiral phase HPLC.

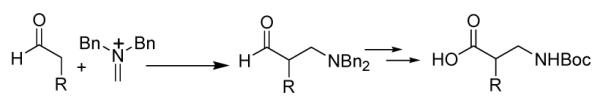

The β-substituted γ-amino alcohols generated via the Mannich/reduction sequence could be converted in a straightforward manner to appropriately protected β2-amino acids as illustrated in Scheme 2. Starting with 5.3 g pentanal 9.7 g A and 10 mol% catalyst F and recrystallizing the HCl salt of the γ-amino alcohol gave a 72% yield of material with > 98% ee. The benzyl groups were removed and replaced by Boc in an efficient one-pot operation. Jones oxidation12 then provided desired β2-amino acid product after simple extraction, with > 50% overall yield from A. The route is short, and purifications are simple; therefore, this protocol is amenable to large-scale synthesis.

Scheme 2.

Concise synthesis of Boc-β2-homonorvaline

We have described catalytic asymmetric Mannich reactions involving a formaldehyde-derived iminium electrophile. Mechanistic analysis of the proline-catalyzed versions suggests that non-H-bonded ionic interactions can be used as a stereochemistry-determining feature in organocatalytic reactions, although in our case a more conventional steric repulsion strategy proved to be more effective for achieving the desired goal. The new organocatalytic process constitutes the key step in an efficient synthesis of β2-amino acids. This contribution is significant because β2-amino acid residues are essential for the formation of certain β-peptide secondary structures (12/10-helix, β3/β2 reverse turn).13 β-Peptides containing β2-residues display useful biological activities, such as mimicry of somatostatin signaling14 and inhibition of viral infection.15 To date, utilization β2-amino acid building blocks has been limited by the cumbersome routes that are generally required to prepare them.4 Few β2-amino acids are commercially available. In contrast, many β3-amino acids (side chain adjacent to nitrogen) are commercially available, and such building blocks are readily prepared from the analogous α-amino acids.16 Our catalytic route offers large-scale access to β2-amino acids, as well as to other chiral molecules (α-substituted β-amino aldehydes, β-substituted γ-amino alcohols) of potential value.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by NIH grant GM56414 and NSF grant CHE-0551920. NMR equipment purchase was supported in part by grants from NIH and NSF, and X-ray equipment by NSF. We thank Dr. Ilia Guzei for analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and compound characterizations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Review: Arend M, Westermann B, Risch N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:1044. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980504)37:8<1044::AID-ANIE1044>3.0.CO;2-E.

- (2)(a).Reviews: Cordova A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:102. doi: 10.1021/ar030231l. Notz W, Tanaka F, Barbas CF., III Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:580. doi: 10.1021/ar0300468.List B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:548. doi: 10.1021/ar0300571. Early studies:List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9336.List B, Porjalev P, Biller WT, Martin HJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:827. doi: 10.1021/ja0174231.Notz W, Sakthivel K, Bui T, Zhong G, Barbas CF., III Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:199.Cordova A, Notz W, Zhong G, Betancort JM, Barbas CF., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:1842. doi: 10.1021/ja017270h. Recent examples: Mitsumori S, Zhang H, Cheong P. Ha-Yeon, Houk KN, Tanaka F, Barbas CF., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1040. doi: 10.1021/ja056984f.Taylor MS, Tokunaga N, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6700. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502277.Poulsen TB, Alemparte C, Saaby S, Bella M, JØrgensen KA. Amgew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:2896. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500144.Lou S, Taoka BM, Ting A, Schaus SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11256. doi: 10.1021/ja0537373.

- (3).Cheng RP, Gellman SH, DeGrado WF. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3219. doi: 10.1021/cr000045i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Reviews: Lelais G, Seebach D. Biopolymers. 2004;76:206. doi: 10.1002/bip.20088.Juaristi E. In: Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Amino Acids. 2nd ed. Soloshonok V, editor. Wiley-VCH; New-York: 2005.

- (5).Cordova et. al. reported formaldehyde derived imine generated in situ with aniline derivatives for aminomethylation of ketones catalyzed by proline, but such strategy is not applicable to aminomethylation of aldehydes. See: Ibrahem I, Casas J, Córdova A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:6528. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460678.Ibrahem I, Zou W, Casas J, Sundén H, Córdova A. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:357.Ibrahem I, Zou W, Engqvist M, Xu Y, Córdova A. Chem.-Eur. J. 2005;11:7024. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500746.

- (6).Examples of using iminium precursors: Hosomi A, Iijima S, Sakurai H. Tetrahedron. Lett. 1982;23:547.Enders D, Ward D, Adam J, Raabe G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:981.Rehn S, Ofial AR, Mayr H. Synthesis. 2003:1790.

- (7).Chi Y, Gellman SH. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4253. doi: 10.1021/ol0517729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hydrogen bonding catalysis: Taylor MS, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1520. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503132.Miller SJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:601. doi: 10.1021/ar030061c.Takemoto Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:4299. doi: 10.1039/b511216h.Pihko PM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2062. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301732.Schreiner PR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003;32:289. doi: 10.1039/b107298f.Pihko PM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2062. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301732.Krattiger P, Kovasy R, Revell JD, Ivan S, Wennemers H. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1101–1103. doi: 10.1021/ol0500259.

- (9).Bahmanyar S, Houk KN. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1249. doi: 10.1021/ol034198e. and ref. 2b.

- (10).See supporting information for details

- (11)(a).Marigo M, Fielenbach D, Braunton A, Kjaersgaard A, JØrgensen KA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:3703. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hayashi Y, Gotoh H, Hayashi T, Shoji M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:4212. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ibrahem I, Córdova A. Chem. Comm. 2006:1760. doi: 10.1039/b602221a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Oxidation of chiral α-substituted aldehydes and alcohols without epimerization: Rangaishenvi MV, Singaram B, Brown HC. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:3286. and ref.7.

- (13)(a).Hintermann T, Seebach D. Synlett. 1997:437. [Google Scholar]; (b) Seebach D, Abele S, Gademann K, Jaun B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:1595. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1595::AID-ANIE1595>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Seebach D, Abele S, Gademann K, Jaun B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:1595. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1595::AID-ANIE1595>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gademann K, Kimmerlin T, Hoyer D, Seebach D. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:2460. doi: 10.1021/jm010816q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).English EP, Chumanov RS, Gellman SH, Compton T. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508485200.Also see: Stephens OM, Kim S, Welch BD, Hodsdon ME, Kay MS, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13126. doi: 10.1021/ja053444+.

- (16).Guichard G, Abele S, Seebach D. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1998;81:187. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.