Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans frequently causes fungal meningitis in immunocompromised patients, whereas the related species Cryptococcus gattii is restricted to tropical/subtropical regions, usually infecting immunocompetent individuals. A C. gattii outbreak that began in 1999 on Vancouver Island is now endemic, causing numerous human and veterinary infections, and has spread to mainland British Columbia. The outbreak isolates are molecular type VGIIa/major or VGIIb/minor. Since 2006, human and veterinary cases have emerged in Washington and Oregon. Multilocus sequence typing demonstrates C. gattii VGIIa and VGIIb spread from Vancouver Island to the Pacific Northwest. Clinical strains from Oregon represent a unique VGIIc genotype.

Keywords: outbreak, fungal pathogen, meningitis, pneumonia, emerging infectious disease

Introduction

Cryptococcus gattii is a basidiomycetous yeast within the Cryptococcus pathogenic species complex [1]. Unlike C. neoformans, which is distributed worldwide, and predominantly infects immunosuppressed patients [1], C. gattii is usually associated with tropical/subtropical climates, and generally causes disease in immunocompetent individuals [1]. C. gattii is subdivided into two serotypes (B and C), and Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) reveals four major C. gattii lineages (VGI-VGIV) [2, 3]. No or limited genetic exchange appears to occur between VG groups, indicating these likely represent cryptic species [2, 3].

C. gattii emerged as a pathogen when it precipitated an outbreak of cryptococcosis on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, which began in 1999 and is ongoing [4, 5]. C. gattii infections on Vancouver Island are caused almost exclusively by two isolates of the VGII molecular genotype (∼90–95%-VGIIa, ∼5–10%-VGIIb) [3, 6]. Although VGII occurs in well-established endemic regions, such as Australia, the most common genotype (in Australia and elsewhere) is VGI [7]. C. gattii can be isolated in endemic areas, and airborne particles have been isolated using air sampling [8, 9]. A recent study reported cases of C. gattii VGII on mainland British Columbia in patients and animals with no Vancouver Island travel history, indicating the outbreak genotype has spread beyond the island [10]. In February 2006, the first confirmed US case of C. gattii caused by the outbreak VGIIa genotype was reported in a patient from Washington [11]. Environmental sources from which C. gattii has been isolated in British Columbia and the US Pacific NW include trees native to the Pacific NW, soil, air, and water [10].

Pathogenic Cryptococcus species routinely reproduce clonally but can also complete a sexual cycle involving a-α opposite or α-α same-sex mating [12, 13]. Studies have identified trees that harbor recombining populations with active mating between a-α or α-α cells [14]. It has been postulated that the spores thus produced are the infectious propagules [13, 15]. Analyses of Vancouver Island outbreak isolates suggests that a hypervirulent genotype may have originated from α-α mating [3]. As no a isolates have been recovered from Vancouver Island, ongoing α-α mating may also contribute to spore production [3].

C. gattii persists as a public health problem on Vancouver Island, and it is clear the organism has spread. A BCCDC surveillance study of C. gattii between 1999 and 2006 documented increasing incidence on Vancouver Island and established spread to the mainland [10, 16]. Our efforts focused on determining whether C. gattii is expanding into the US, and if so, the relationship of the isolates to the Vancouver Island outbreak genotypes. Our results document infections in humans and mammals, indicating an expansion of VGIIa from Vancouver Island to the US Pacific Northwest. In addition to the VGIIa and VGIIb genotypes, we identified a divergent VGIIc cluster that has infected humans and other mammals. The VGIIc genotype is distinct from other isolates analyzed thus far, with the exception of a clinical isolate from Oregon identified in 2007 [10]. In addition, the first infection with a VGIII isolate in the region was noted. These data reveal an expansion of the outbreak beyond Vancouver Island, establishment within the US, a distinct VGII genotype (VGIIc) found in the US [10], and invasion of the US by a VGIII isolate. The origins of C. gattii VGIIa on Vancouver Island and the VGIIc molecular genotype present in the US but not Vancouver Island remain to be elucidated.

Materials and Methods

Case and Isolate Identification

Human and veterinary cases of confirmed or suspected C. gattii infections in Washington and Oregon were identified by referring physicians and veterinarians (see Acknowledgements) (Table S1).

Genotyping

For MLST [17], each isolate was analyzed with a minimum of eight unlinked loci. For each isolate, genomic DNA was extracted, amplified, purified and sequenced.

Results

Clinical C. gattii Isolates from Washington and Oregon

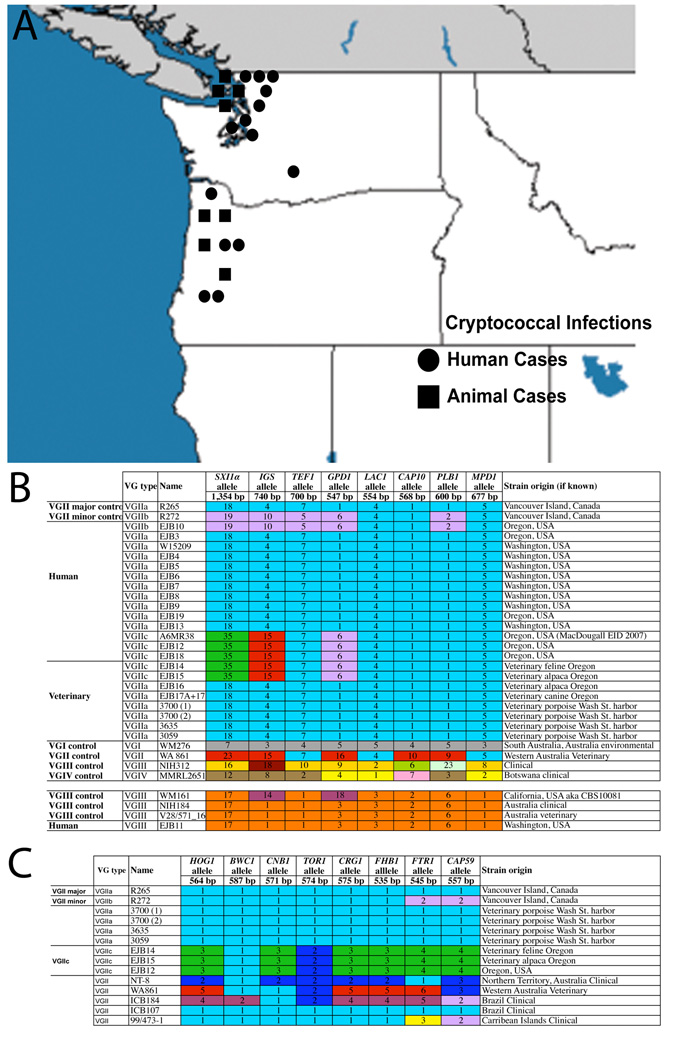

Between 2006 and 2008, we were informed of 14 human and eight veterinary cases of confirmed C. gattii infection in the Pacific NW (Table S1). The geographic origin of these cases spans much of Washington and Oregon (Figure 1A). The veterinary cases involved a range of animals, including porpoises, alpacas, cats and dogs.

Figure 1.

A) C. gattii cases in animals and humans in Washington and Oregon during 2006–2008. All cases represented have been confirmed using phenotypic analysis and Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) genotypic profiling. There are a total of 22 cases, including thirteen in Washington State and nine in Oregon, United States. Of the 22 cases fourteen are human clinical isolates, and eight are isolates from deceased wild and companion animals. B) MLST reveals VGIIa major, VGIIb minor, and VGIIc isolates in Washington and Oregon. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) was performed for eight unlinked loci. Numbers and color-coding represent different alleles designated by genetic sequence variation. The lone VGIII isolate was an identical match to only Australian isolates, indicating its possible origin. C) Expanded Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) analysis for selected VGII isolates, including VGIIc isolates. Six of the eight additional alleles were novel among the VGIIc isolates tested. Isolates WA861 and ICB184 were examined as other closely related VGII isolates to the VGIIc group, with MLST analysis providing further evidence that the VGIIc group is not closely related to these isolates.

Isolates were confirmed as C. gattii based on melanin and urease production, and resistance to canavanine with glycine utilization on CGB agar. All isolates (except EJB11) have the VGII molecular type. While the VGII isolates from Washington are the major molecular type (VGIIa), the population in Oregon was more diverse. For additional information about the isolates, see Table S1 and Figure 1B.

Genomic DNA of each isolate was analyzed by MLST (Figure 1B). To determine the mating type of each isolate, PCR and sequence analysis were used to detect mating-type specific alleles of the SXI genes. Based on sequence analysis of the sex-specific SXI1α mating type gene, as well as the absence of the SXI2a gene, all isolates are MATα. Twelve of the 13 isolates from Washington were identical to the VGIIa major genotype. The exception was a novel VGIII strain isolated from a case in southern Washington State. Eleven of the 12 VGIIa cases in Washington were recovered from the coastal Puget Sound region; the remaining isolate was from a clinical case in Seattle. In addition, occurrence of cryptococcosis in marine mammals is a potential harbinger of dispersal. These findings document spread of the outbreak major genotype from Vancouver Island into Washington.

To date, all C. gattii isolates isolated from the NW region of Washington belong to the VGIIa major outbreak genotype. Isolates from Oregon were also VGII, but more diverse. Oregon isolates grouped into three genotypes: VGIIa, VGIIb, and VGIIc. The VGIIb molecular type is found in both Australia and Vancouver Island, while the VGIIc molecular type is distinct from other global VGII molecular types, although it shares some MLST alleles with both VGIIa and VGIIb. The VGIIc isolates are noteworthy because they have never been found on Vancouver Island, mainland BC, or Washington, but were recovered from both patients and animals in Oregon.

Despite sharing alleles with other VGII strains, based on sequence analysis the VGIIc genotype is unique. MLST analysis of eight loci indicated that this group shares five loci with VGIIa and one locus each with VGIIb and VGII isolates; in addition, VGIIc has one novel allele not seen in any other VGII genotypes, and was also shown to be distinct in a previous study (Figure 1B) [10]. Expanding this analysis to eight additional MLST loci, the VGIIc group was found to share another locus with the VGIIa group, the TOR1 locus with a divergent VGII isolate and contains novel alleles at six additional loci (Figure 1C). The discovery of VGIIc, coupled with the recent cases of cryptococcal disease, mark the emergence of a new VGII molecular type in this region.

The lone VGIII isolate, which is molecularly distinct from VGII and therefore unrelated to the outbreak, was recovered in southern Washington, distant from the outbreak expansion zone (Figure 1). Most VGIII subgroup isolates are serotype C, and more commonly infect immunosuppressed patients, such as patients with AIDS [3, 18, 19]. While this VGIII case is not part of the VGII outbreak expansion, its discovery provides evidence of an increased regional incidence of C. gattii and highlights the need to molecularly classify clinical isolates of Cryptococcus.

Discussion

Our findings document an expansion of the Cryptococcus gattii outbreak from British Columbia to Washington and Oregon. This conclusion is based on extensive MLST typing demonstrating isolates identical to VGIIa/major and VGIIb/minor Vancouver Island outbreak genotypes in the United States. This illustrates an increased risk for infection, as well as an expansion of the native endemic zone for this pathogenic fungus. Based on travel history, most of these cases were not the result of exposure on Vancouver Island or in Canada. As a consequence, C. gattii infections are increasing as an emerging infectious disease in the Pacific NW.

In addition to the significant human risks, there is also an expanding risk to wild, agrarian, and companion terrestrial animals, as well as marine mammals [8]. Furthermore, occurrence of disease in non-migratory animals provides further evidence that these isolates were acquired locally in Washington and Oregon. With the exception of a few anomalous cases, cryptococcosis is not transmissible among animals or humans.

The expansion of C. gattii is likely abetted by increasing human traffic and animal migration. A previous environmental survey of C. gattii in BC and the NW Pacific states documented the perennial colonization of certain locales as well as evidence of ongoing dispersal associated with human travel; however, no isolates were recovered from Oregon [20]. In addition, an increase in airborne C. gattii has been detected in forestry areas, indicating that disruption of trees may foster its spread [20]. It is likely that both anthropogenic and natural dispersal in the region are occurring.

Another open question with respect to the outbreak and its expansion is the contribution, if any, of spores generated by same-sex or opposite sex mating. Spores are smaller than vegetative yeast cells, easily disseminated, and highly infectious [15]. The sexual cycle might also generate recombinant progeny with altered virulence. Vancouver Island air sampling revealed particles small enough to be spores [20]. The recent finding that Cryptococcus co-cultured with plants stimulates sexual reproduction, suggests how infectious spores might be produced in nature [21].

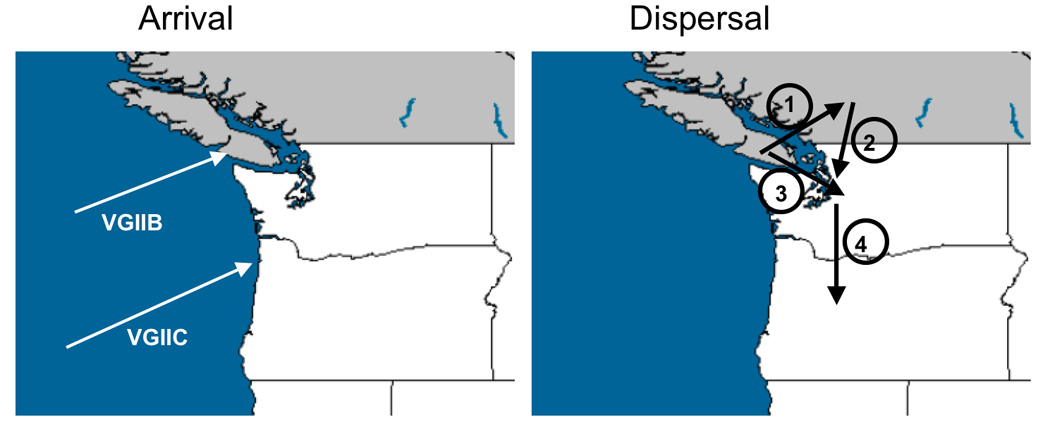

It is unclear how frequently mating occurs in natural populations of C. gattii. In Australia, both a-α and α-α mating have been observed in natural populations [14], but in the Pacific NW where no a isolates have been identified, α-α mating may be more common. In one model, VGIIb arrived from Australia, and recombined in transit or upon arrival through same-sex mating to form the VGIIa outbreak genotype, which then expanded to BC, and the Pacific NW [3](Figure 2). The emergence of VGIIc is less clear and may have come from outside the region, or may be a recombined isolate (Figure 2). Increased sampling may enable the origin of this genotype to be elucidated.

Figure 2.

Origin of an outbreak. Left panel) The arrival of minor and novel recombinant genotypes. Right panel) The dispersal of the VGIIa major, and VGIIb minor genotypes from Vancouver Island to the British Columbia mainland (1), from the British Columbia mainland to the United States (2), from Vancouver Island to the United States (3), and from Washington to Oregon (4).

While same-sex mating is a plausible hypothesis for a recombination event spawning the outbreak, an alternative hypothesis is that the Vancouver Island outbreak is the result of opposite-sex mating, possibly in South America, giving rise to the outbreak isolate [3, 22]. An investigation of C. gattii in Colombia recently discovered a population with 96.6% serotype B a isolates [22]. Considering that the VGIIb outbreak genotype is identical at 30 MLST loci to isolates in fertile recombining Australian populations [9, 23], and that all of the outbreak isolates including those identified here are α, we favor the α-α mating hypothesis, although studies are needed to understand whether a-α recombination is occurring in South America and its impact.

While the origin of the VGIIa outbreak genotype has not been resolved, the expansion of both outbreak genotypes into neighboring regions is clear. It is likely that one or more isolates reached Vancouver Island directly and the endemic zone is now expanding to mainland BC and the US. The timeline for the outbreak, and expansion into mainland Canada correlate well with expansion rather then an ascertainment bias from increased surveillance. Retrospective case reviews identified no C. gattii cases in the Pacific Northwest United States during 1997–2004 [11], while current prospective studies have revealed ∼20 cases since the 2006 US index case [11]. Our studies provide insights into expansion of this outbreak, and indicate a clear need for future studies, as well as vigilant public health reporting. In addition, novel molecular types including VGIIc may have directly entered the US or conversely may have never become established or thus far escaped detection on Vancouver Island. Although cases of C. gattii in Oregon have occurred in humans and animals, the environmental niche remains elusive. Ecological studies of C. gattii in the Oregon environment are needed to determine the likely reservoirs, and enable an understanding of population structures. This approach should shed further light into the dynamics of an emerging pathogen, and help clarify influences that affect origins and expansion of microbial pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah West, Robert Barnes, Robert Thompson, Ajit Limaye, Claire Beiser, Sara Mostad, and Karen Bartlett for human isolates from Washington and Oregon, Stephen Raverty for marine mammal isolates and case information from Puget Sound, Peggy Dearing for veterinary isolates, Leon Razai and Anastasia P. Litvintseva for technical support, and Chaoyang Xue, Anastasia P. Litvintseva, and John R. Perfect for reading the manuscript.

Funding. This work was supported by NIH/NIAD R01 grant AI39115 to JH and AI25783 to TGM.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. None reported.

References

- 1.Casadevall A, Perfect J. Cryptococcus neoformans. Washington DC: ASM Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bovers M, Hagen F, Kuramae EE, Boekhout T. Six monophyletic lineages identified within Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by multilocus sequence typing. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45:400–421. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser JA, Giles SS, Wenink EC, et al. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437:1360–1364. doi: 10.1038/nature04220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoang LM, Maguire JA, Doyle P, Fyfe M, Roscoe DL. Cryptococcus neoformans infections at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre (1997–2002): epidemiology, microbiology and histopathology. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:935–940. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephen C, Lester S, Black W, Fyfe M, Raverty S. Multispecies outbreak of cryptococcosis on southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Can Vet J. 2002;43:792–794. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidd SE, Hagen F, Tscharke RL, et al. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17258–17263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402981101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med Mycol. 2001;39:155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidd SE, Guo H, Bartlett KH, Xu J, Kronstad JW. Comparative gene genealogies indicate that two clonal lineages of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia resemble strains from other geographical areas. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1629–1638. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.10.1629-1638.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell LT, Fraser JA, Nichols CB, Dietrich FS, Carter D, Heitman J. Clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus gattii from Australia that retain sexual fecundity. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1410–1419. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1410-1419.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDougall L, Kidd SE, Galanis E, et al. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and detection in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:42–50. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upton A, Fraser JA, Kidd SE, et al. First contemporary case of human infection with Cryptococcus gattii in Puget Sound: evidence for spread of the Vancouver Island outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3086–3088. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00593-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser JA, Subaran RL, Nichols CB, Heitman J. Recapitulation of the sexual cycle of the primary fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: implications for an outbreak on Vancouver Island, Canada. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1036–1045. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.1036-1045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saul N, Krockenberger M, Carter D. Evidence of recombination in mixed-mating-type and alpha-only populations of Cryptococcus gattii sourced from single eucalyptus tree hollows. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:727–734. doi: 10.1128/EC.00020-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sukroongreung S, Kitiniyom K, Nilakul C, Tantimavanich S. Pathogenicity of basidiospores of Filobasidiella neoformans var. neoformans. Med Mycol. 1998;36:419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.BC Centre for Disease Control. BC Cryptococcus gattii Surveillance Summary, 1999–2006, 2007

- 17.Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaturvedi S, Dyavaiah M, Larsen RA, Chaturvedi V. Cryptococcus gattii in AIDS patients, southern California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1686–1692. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.040875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litvintseva AP, Thakur R, Relier LB, Mitchell TG. Prevalence of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus gattii serotype C among patients with AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:888–892. doi: 10.1086/432486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidd SE, Bach PJ, Hingston AO, et al. Cryptococcus gattii dispersal mechanisms, British Columbia, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:51–57. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue C, Tada Y, Dong X, Heitman J. The human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus can complete its sexual cycle during a pathogenic association with plants. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escandon P, Sanchez A, Martinez M, Meyer W, Castaneda E. Molecular epidemiology of clinical and environmental isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex reveals a high genetic diversity and the presence of the molecular type VGII mating type a in Colombia. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:625–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell LT, Currie BJ, Krockenberger M, et al. Clonality and recombination in genetically differentiated subgroups of Cryptococcus gattii. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1403–1409. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1403-1409.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.