Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of irreversible blindness in the world. Although the etiology and pathogenesis of AMD remain largely unclear, a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors is thought to exist. AMD pathology is characterized by degeneration involving the retinal photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium, and Bruch’s membrane, as well as, in some cases, alterations in choroidal capillaries. Recent research on the genetic and molecular underpinnings of AMD brings to light several basic molecular pathways and pathophysiological processes that might mediate AMD risk, progression, and/or response to therapy. This review summarizes, in detail, the molecular pathological findings in both humans and animal models, including genetic variations in CFH, CX3CR1, and ARMS2/HtrA1, as well as the role of numerous molecules implicated in inflammation, apoptosis, cholesterol trafficking, angiogenesis, and oxidative stress.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, Inflammation, Single nucleotide polymorphism, Genetics, Retinal pigment epithelium, Retinal photoreceptors, Drusen, Vascular endothelial growth factor, Bruch’s membrane, Molecular pathology

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology of AMD

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) was first described in the medical literature in 1875 as “symmetrical central choroidoretinal disease occurring in senile persons” (Hutchison and Tay, 1875). According to the most recent report on the causes of visual impairment by the World Health Organization in 2002, AMD is among the most common causes of blindness, particularly irreversible blindness, in the world. Among the elderly, AMD is regarded as the leading cause of blindness in the world (Gehrs et al., 2006). Currently, in the United States alone, 1.75 million people are affected by AMD and 7 million people are at risk of developing AMD (Friedman et al., 2004). Considering the significant medical, personal, social, and economic costs of AMD, the need for novel therapeutic and preventative strategies for AMD is pressing. Innovation in AMD pharmacotherapy, in turn, depends largely upon a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying AMD pathogenesis.

1.2. Risk factors for AMD

AMD is a highly complex disease with demographic, environmental, and genetic risk factors. Among demographic and environmental factors associated with AMD, such as age, gender, race, diet, smoking, education, cardiovascular disease, studies have shown that the most established factors are advanced age, cigarette smoking, diet, and race (Coleman et al., 2008; Jager et al., 2008). The age-associated increase in AMD risk might be mediated by gradual, cumulative damage to the retina from daily oxidative stress. Loss of normal physiological function in the aging retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, a specialized neural cell of neuroectoderm origin that provides metabolic support to photoreceptor cells, may also contribute to the formation of drusen deposits classically seen in AMD retina. Alternatively, age-related mitochondrial DNA damage might also play a role in pathogenesis. Further studies on the impact of aging on the structure and function of the retina are certainly necessary to parse out the key pathological changes that lead to AMD.

The relationship between smoking and AMD has been investigated in numerous cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, and case-control studies (Klein, 2007). The majority of studies have found a statistically significant association between smoking and development of AMD. Possible mechanisms by which smoking mediates increased AMD risk include impairment in the generation of antioxidants (e.g. plasma vitamin C and carotenoids) induction of hypoxia, generation of reactive oxygen species, and alteration of choroidal blood flow. Smoking also has an effect on the immune system (Tsoumakidou et al., 2008). Based on studies (discussed below) demonstrating an immunological component for AMD, it is possible that part of the risk conferred by smoking funnels through inflammatory pathways. This remains to be demonstrated experimentally.

Both fat intake and obesity have been linked to increased risk of AMD (Mares-Perlman et al., 1995; Seddon et al., 2003), and analyses have revealed protective effects from antioxidants, nuts, fish, and omega-3 polysaccharide unsaturated fatty acids (AREDS, 2001; Cho et al., 2001; Seddon et al., 1994, 2001; Smith et al., 2000). Several convincing studies of the dietary effect on AMD are from randomized controlled clinical trials, e.g., Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS), VEGF (Vascular endothelial growth factor) Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization, Clinical Trial and Minimally Classic/Occult Trial of the Anti-VEGF Antibody Ranibizumab in the Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (MARINA) (AREDS, 2001; Bressler et al., 2003; Gragoudas et al., 2004; Rosenfeld et al., 2006). The AREDS demonstrated the efficacy of zinc-antioxidant supplements for preventing or delaying progression of early AMD to late AMD in patients who are at high risk (Bressler et al., 2003). A recent population-based cohort study in Australia (Tan et al., 2008) demonstrated that high dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake reduced the risk of long-term incident AMD and that high beta-carotene intake was associated with an increased risk of AMD.

Studies on genetic determinants of AMD have developed slowly because (1) AMD is a disease of old age, surviving parents and well-established family trees are rare; (2) AMD is likely to be a complex disease with numerous etiological factors; (3) the completion of the Human Genome Project with the access to human genome sequence data was only 5 years ago. Instead of having a single contributory gene, a polygenic pattern with multiple genes of variable effect may be involved. Considerable evidence in family, twin and sibling studies exists and suggests a genetic basis of AMD. Several family studies have shown that patients with a family history of AMD are at increased risk (Seddon et al., 2007; Smith and Mitchell, 1998). Recently, Luo et al. identified 4764 AMD patients, analyzed the familial aggregation and estimated the magnitude of familial risks in a population-based cross-sectional and case-control study. The results showed that for AMD, the population-attributable risk (PAR) for a positive family history was 0.34. Recurrence risks in relatives indicate increased relative risks in siblings (2.95), first cousins (1.29), second cousins (1.13), and parents (5.66) of affected cases (Luo et al., 2008). Many linkage and association studies have indicated that the most replicated signals reside on chromosome 1q25–31 and 10q26 (Fisher et al., 2005; Jakobsdottir et al., 2005; Klein et al., 1998; Majewski et al., 2003). We will discuss the genetic factors underlying AMD pathology further in the “single nucleotide polymorphisms” and “molecular pathology of AMD” sections below.

In this article, we review the histopathologic findings that define AMD, along with new molecular pathologic findings that have advanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of AMD pathogenesis.

2. Pathology of AMD

The progression of AMD occurs over an extended time frame, with the incidence of the disease increasing dramatically over the age of 70. AMD is a multifactorial disease that affects primarily the photoreceptors and RPE, Bruch’s membrane, and choriocapillaries. Aging is associated with changes in the retina, including alterations in RPE cellular size and shape, thickening of Bruch’s membrane, thickening of the internal limiting membrane, and a decrease in retinal neuronal elements (Green, 1996).

Classically, subretinal, extracellular deposits composed of glycoproteins and lipids accumulate in Bruch’s membrane. These dumbbell shaped deposits are called drusen (singular ‘druse’). The presence of a few small hard drusen in the peripheral retina is considered a normal part of the aging process. However, the presence of large and many drusen in the macula signifies early AMD. The presence of inflammation-related molecules in drusen suggests the possible involvement of the immune system in AMD pathogenesis (Hageman et al., 2001). A recent study of age-related changes demonstrates recruitment of leukocytes and activation of the complement cascade in mouse RPE and choroid (Chen et al., 2008). These age-related changes may provide the background for AMD development in elderly individuals with genetic predisposition. The main pathological changes associated with AMD vary with AMD stage and are described below.

2.1. Early stage AMD

Early AMD is characterized by thickening and loss of normal architecture within Bruch’s membrane, lipofuscin accumulation in the RPE, and drusen formation beneath the RPE in Bruch’s membrane (Fig. 1). The earliest pathological changes are the appearance of basal laminar deposits (BlamD) and basal linear deposits (BlinL) (Green and Enger, 1993). BlamD consist of membranogranular material and foci of wide spaced collagen between the plasma membrane and basal lamina of the RPE. BlinL consist of vesicular material located in the inner collagenous zone of Bruch’s membrane and represent a specific marker for AMD (Curcio and Millican, 1999).

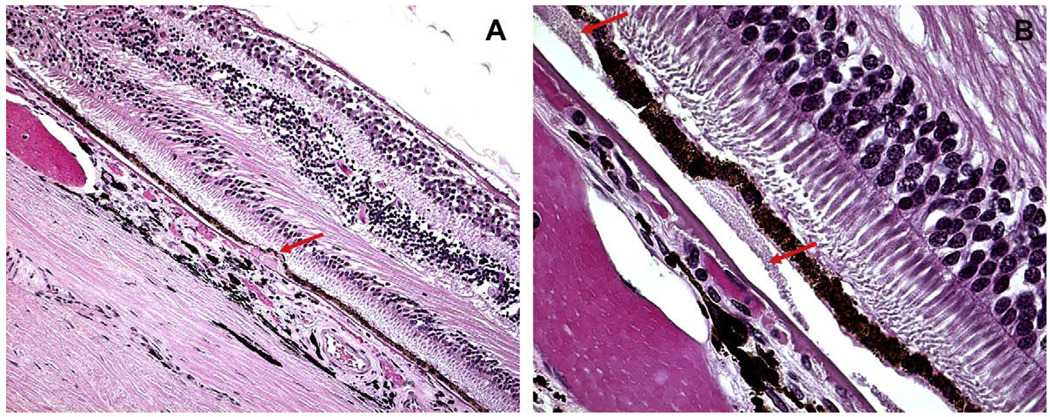

Fig. 1.

Hard and soft drusen. (A) Hard drusen, a small, discrete, punctate druse (arrow) with hyaline-like material located beneath the basal cell surface of the RPE and in Bruch’s membrane. (B) Soft drusen, large dome-shaped, hyaline granular deposits with poorly demarcated boundaries (arrow) beneath the RPE. Bruch’s membrane is thickened.

Drusen, derived from the German word for geodes, cavities in rocks often lined by crystals, are localized deposits lying beneath the basement membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) into Bruch’s membrane. Drusen in AMD are most frequently found as clusters within the macular region. They vary in size, shape, color, consistency, and distribution, and they tend to increase in number with advancing age. In the earliest stage, they may be visible ophthalmoscopically, when their diameter exceeds 25 µm (Sarks et al., 1999), as semi-translucent punctate dots in retro-illumination. As the overlying RPE thins, drusen are more obvious as yellow-white deposits.

Clinically, drusen are classified morphologically either as hard or soft. Hard drusen, which are relatively common in elderly patients with or without AMD, appear clinically as small, yellowish, and punctuated deposits that are less than 63 µm in diameter. The presence of drusen, especially drusen that are few in number and hard in quality, is not considered a particularly important risk factor for the development of AMD. In contrast, soft drusen, which are characterized by a more diffuse, paler and larger appearance, perhaps with ‘fuzzy’ or blurry edges, signify early AMD. The large drusen, bilateral drusen, and/or numerous drusen, are significant risk factors for development of late stage AMD. The larger the drusen, the greater the area they cover, and the larger the areas of hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation of the RPE in the macula, the higher the risk of late age-related macular degeneration is (Klein et al., 2002).

The molecular and cellular constituents of drusen have been analyzed extensively (Anderson et al., 2004; Crabb et al., 2002; Hageman et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2000; Mullins et al., 2000; Russell et al., 2000). Complement components, other inflammatory molecules, lipids, lipoproteins B and E, and glycoproteins are common constituents of ocular drusen (Johnson et al., 2002). Immunohistochemical analyses have shown various molecular constituents, such as apolipoproteins B and E, different immunoglobulins, factor X, amyloid P component, amyloid β, complement C5 and C5b-9 terminal complexes, fibrinogen, vitronectin, and others, to be present in all phenotypes of hard and soft drusen (Anderson et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2000; Mullins et al., 2000; Nozaki et al., 2006). Their precise functional role in the pathogenesis of AMD is not entirely clear, although it has long been recognized that drusen are the hallmark lesions of AMD.

2.2. Late stage AMD

The primary clinical characteristic of late stage ‘dry’ AMD is the appearance of RPE atrophy, usually known as geographic atrophy. Geographic atrophy is characterized by roughly oval areas of hypopigmentation and is usually the consequence of RPE cell loss. Loss of RPE cells responsible for servicing the overlying photoreceptors leads to the gradual degeneration of nearby photoreceptors, resulting in thinning of the retina (Fig. 2) and a progressive visual impairment. In severe cases, retinal atrophy may extend to the outer retinal layers including the outer plexiform and inner nuclear layers. Hyperpigmentary changes associated with compensatory RPE cell proliferation are frequently observed at the periphery of these hypopigmented areas (de Jong, 2006).

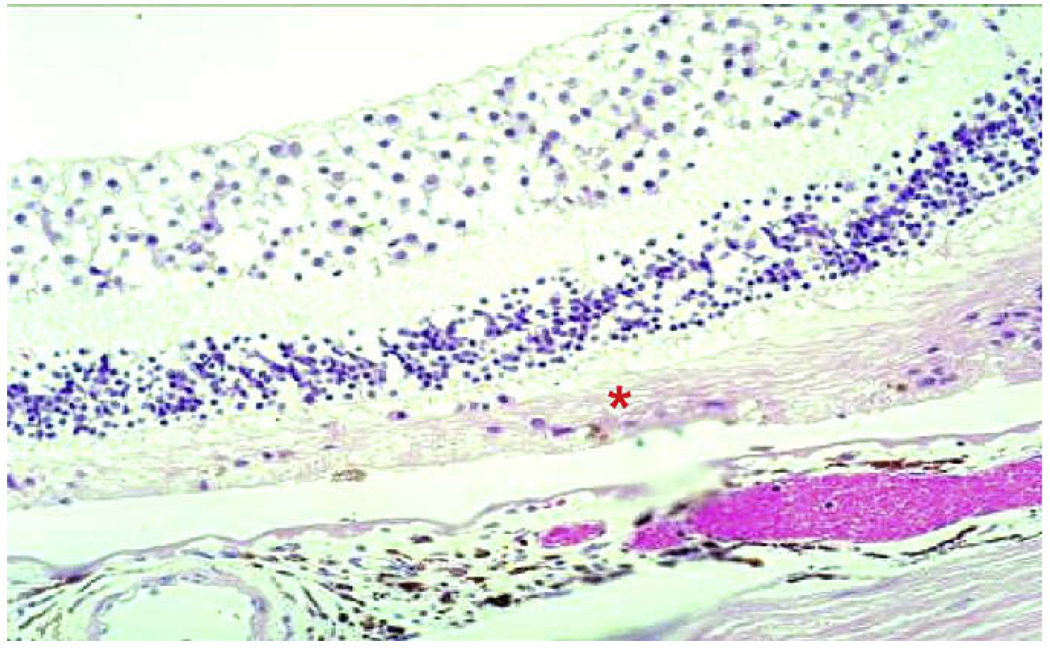

Fig. 2.

Geographic atrophy in AMD. There is degeneration of RPE cells and most of the photoreceptors (asterisk).

Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is the defining characteristic of late stage ‘wet’ or neovascular AMD. Classical neovascular AMD is mainly illustrated with CNV and subretinal neovascular fibrous tissue (Fig. 3). The neovascularization has two etiologic patterns: (1) new vessels sprouting from the choroidal vessels, penetrating Bruch’s membrane and growing into the subretinal space are the classical descriptions of wet AMD (Green, 1999), which is most common; and (2) vessels that are derived mainly from the retinal circulation in a process that has been called retinal angiomatous proliferations (RAP), also called deep retinal vascular anomalous complex or retinochoroidal anastomosis (Brancato et al., 2002; Donati et al., 2006; Ghazi, 2002; Hunter et al., 2004; Yannuzzi et al., 2001). RAP refers to new vessel development extending outward into the subretinal space from the neurosensory retina, sometimes anastomosing with the choroid-derived vessels (Lafaut et al., 2000). RAP, however, occurs much less frequently than the classical choroid-derived neovascular vessels.

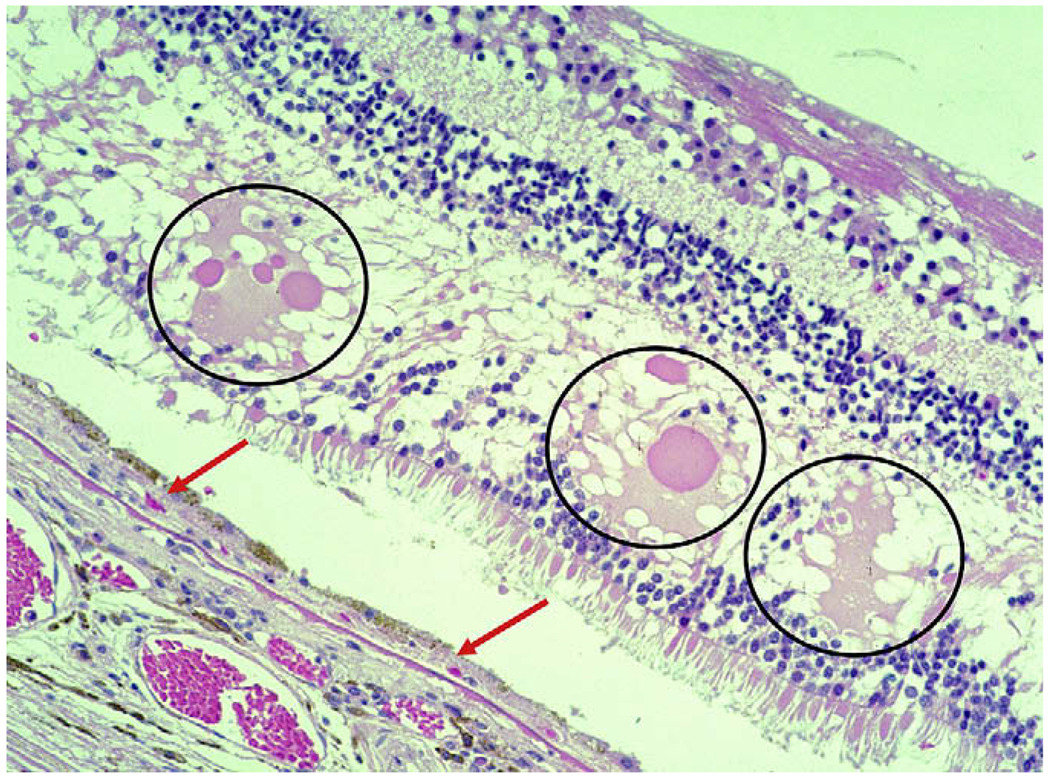

Fig. 3.

Neovascular AMD. There is a thin layer of fibrovascular membrane (CNV) between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane (arrows). Serous fluid (circles) due to leakage from neovascular membranes is seen in the outer plexiform layer of the retina.

3. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and molecular pathology of AMD

3.1. Single nucleotide polymorphism

With the sequencing of the human genome and improved DNA sequencing and mapping technologies, recent years have seen an explosion of genetic studies identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) which confer increased or decreased risk of disease (Smith, 2005). AMD is no exception, as SNPs associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and other pathological processes have been linked to AMD. Investigation of the expression of these genes and their functional properties in AMD cases have led to a deeper understanding of the pathological mechanisms of AMD.

3.2. Complement system

While AMD is a highly complex disease with numerous intersecting etiological factors, recent studies have generated significant interest in the inflammatory underpinnings of AMD pathogenesis (Klein et al., 2008b). These studies have been buttressed by genetic studies identifying inflammation-associated SNPs that modulate AMD risk. These SNPs lie in genes encoding complement factors, chemokines and chemokine receptors, and toll-like receptors.

3.2.1. Complement factors and AMD pathology

The complement system of innate immune system includes over 30 proteins, which are activated by immune complexes, residues on microbial cell surfaces, and other triggers. Activation of the complement system generates a variety of pro-inflammatory responses, including the production of membrane-attack complexes (MAC) which lead to cell lysis, release of chemokines to mediate recruitment of inflammatory cells, and enhancement of capillary permeability (Walport, 2001a, b). While complement activity is crucial for the immune responses against pathogens or dying cells, dysregulation of the cascade can result in complement overactivation-mediated damage to nearby healthy tissue.

A number of studies have illustrated the presence of complement components and complement regulatory proteins in drusen and nearby RPE of AMD patients (Crabb et al., 2002; Hageman et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2000; Mullins et al., 2001; Nozaki et al., 2006), suggesting a role for complement in AMD pathogenesis (Bora et al., 2008). These studies have been matched by genetic association studies. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that animal models with complement knockdown, either genetically or with pharmacological agents such as anti-complement antibodies, exhibit decreased CNV after laser injury, a commonly employed model for AMD-associated CNV in humans (Patel and Chan, 2008).

3.2.2. Complement factor H (CFH)

3.2.2.1. CFH SNP and AMD

CFH is encoded within the interval of chromosome 1q23–32, a region associated with AMD previously through linkage studies (Klein et al., 1998). A major AMD-associated SNP is the Y402H (tyrosine to histidine substitution at amino acid 402) variant of complement factor H (CFH) (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005). CFH is now widely accepted as an important AMD susceptibility gene, harboring variants and haplotypes associated with increased and reduced disease risk. CFH is identified in normal RPE and choroid (Klein et al., 2005).

CFH is a negative regulator of the complement system. The C3b–Bb complex is a key component of the alternative pathway, and CFH inhibits the alternative pathway by promoting Factor I-mediated inactivation of C3b or by displacing Factor Bb from the C3bBb complex (Alsenz et al., 1985). Given the abundance of complement components, including alternative pathway components, in drusen of AMD, it is possible that impaired complement inhibitory activity by CFH contributes to AMD pathogenesis.

The risk-conferring Y402H CFH variant (genotype CC) has also been reported to reduce the binding affinity to C-reactive protein (CRP), a pro-inflammatory molecule, as compared with the Y402Y variant (genotype TT). This suggests that reduced binding of CRP by CFH might lead to impaired targeting of CFH to cellular debris (Laine et al., 2007; Skerka et al., 2007). In comparing the Y and H variants of CFH, Yu et al. also show no significant difference in their protein secretion, cofactor activity, or interaction with heparan, but a significant difference in binding to CRP (Yu et al., 2007). Moreover, elevated serum level of CRP has been shown to be associated with AMD (Mold et al., 1999; Seddon et al., 2004).

CFH dysfunction may lead to excessive inflammation and tissue damage involved in the pathogenesis of AMD (Johnson et al., 2006). Using confocal immunohistochemical analysis, Johnson and associates illustrated that individuals homozygous for the risk-conferring Y402H CFH variant have higher levels of CRP in the choroid compared to individuals homozygous for the “normal” Y402 variant. In contrast, there is no significant difference between the two phenotypes (YY and HH) in the amount of CFH protein in the RPE-choroid complex (Johnson et al., 2006). These results support the notion that the association between CFH polymorphisms and AMD may involve CRP. For example, impaired binding of CRP by the risk-conferring CFH variant might lead to accumulation of CRP in the choroid. However, a recent publication indicates that CFH binds to the denatured rather than native CRP, thus casting some doubt upon this link between CFH and CRP (Hakobyan et al., 2008). It is also possible that persistent chronic inflammation that is a byproduct of attenuated complement-inhibitory activity may occur in those individuals with the risk-conferring CFH SNP Y402H and that this pro-inflammatory state, rather than impaired binding by CFH, leads to CRP accumulation in AMD retina. Alternatively, the role of CFH in AMD might be completely independent of CRP. Without a doubt, further studies are necessary to dissect the role, if any, of the CFH Y402H SNP in AMD pathogenesis.

In addition to the CFH Y402H (dbSNP ID: rs1061170) SNP, 5 other CFH variants (rs3753394, rs800292, rs1061147, rs1061170, rs380390, and rs1329428) have been reported in AMD association studies. The three SNPs at rs1061147, rs1061170, and rs380390 are in complete linkage disequilibrium (LD). Among them, the rs1061170 (Y402H) was the only SNP that leads to a non-synonymous amino acid change. These SNPs have been reported to be major genetic factors for developing AMD in Caucasians (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005; Tuo et al., 2006). In the Chinese and Japanese populations, only three of these CFH SNPs–at rs1329428, rs800292 (I62V), and rs3753394, but not at rs1061170 (Y402H)–were associated with risk of exudative AMD (Chen et al., 2006; Okamoto et al., 2006). Thus, studies to date demonstrate an association between CFH and AMD. The particular SNPs associated with AMD, however, depend upon the study and the study population. It is possible that CFH could play a central role in AMD pathogenesis and that multiple SNPs that impact CFH function might contribute to the development of AMD.

3.2.2.2. Association between the CFH SNP and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection

Recently, some studies have suggested a potential role for Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in AMD pathogenesis. AMD patients have been found to possess increased serum anti-C. pneumoniae antibodies, and these antibodies have been linked to increased risk of AMD progression (Robman et al., 2005). Moreover, C. pneumoniae has been found in AMD neovascular membranes (Kalayoglu et al., 2005).

C. pneumoniae is a potent activator of the alternative complement system and thus, its effects might be mediated through complement over-activation. This notion is supported by a recent study demonstrating that the presence of the risk-conferring CFH variant and high C. pneumoniae antibody titer significantly increases AMD risk, well beyond the risk associated with possessing either risk factor alone (Baird et al., 2008). Whether this interaction is synergistic or additive is unclear. Since C. pneumoniae is a trigger for the alternative complement pathway, it is possible that once triggered, the alternative pathway runs unabated in patients with the risk-conferring CFH variant, leading to AMD pathogenesis. It is also possible that a low-grade inflammation from persistent C. pneumoniae infection may also predispose to AMD and that the contribution of C. pneumoniae and CFH to AMD may be simply additive.

We recently found no relationship between risk-conferring CFH variant and C. pneumoniae in 148 advanced AMD patients and 162 control subjects with the infection, although there is a positive association between AMD and C. pneumoniae infection (20% vs. 10% positive C. pneumoniae DNA detected in the blood of AMD patients compared with the controls) (Shen et al., 2008). Therefore, CFH may not be directly involved in the pathogenesis of C. pneumoniae infection-mediated AMD. Further studies are indeed warranted to determine whether a link exists between C. pneumoniae and CFH in AMD pathogenesis.

3.2.2.3. CFH SNP genotype and therapeutic responses

Analyzing the response to treatment in AREDS patients, Klein et al. recently observed an interaction between the CFH Y402H genotype and supplementation with antioxidants and zinc. In individuals homozygous for the non-risk phenotype (Y402Y/Y402Y), 34% of those treated with placebo progressed to advanced AMD, compared with 11% of those treated with antioxidants plus zinc, a reduction of approximately 68%. In contrast, in individuals homozygous for the risk-conferring phenotype (Y402H/Y402H), 44% of those treated with placebo group progressed to advanced AMD, compared with 39% of those treated with antioxidants plus zinc, a reduction of only 11% (Klein et al., 2008a). In addition, a similar interaction was observed in the groups taking zinc versus those taking no zinc: zinc intake had a more dramatic protective effect in patients with non-risk alleles, compared with patients with risk alleles. These results suggest that the zinc plus antioxidative treatment seems to have less impact on those with the high-risk CFH variant. Similarly, Brantley et al. investigated 86 wet AMD patients to determine whether there is an association between CFH genotypes and response to treatment with intravitreal bevacizumab. The results show that only 10.5% of patients with the risk-conferring Y402H/Y402H phenotype demonstrated improved vision with treatment, compared with 53.7% of patients with the Y402Y/Y402Y and Y402Y/Y402H CFH variants (P = 0.004) (Brantley et al., 2008). The underlying mechanism of this genotype-response association is still elusive, and more studies are warranted before any definitive conclusions are drawn.

3.2.3. Complement factor B (BF), complement component 2 (C2), C3, C7, and complement factor I (FI)

Complement component 2 (C2) is paralogous to complement factor B (BF) and resides adjacent to BF on chromosome 6p21.3, and haplotypes in BF and C2 have been linked to AMD. In particular, the L9H BF/E318D C2 and R32Q BF/intronic variants of C2 have been shown to be protective for AMD (odds ratio (OR) = 0.45 and 0.36, respectively) by Gold et al. Gold and his colleagues hypothesized that the significance of the haplotypes is due largely to the BF variants, which are in strong linkage disequilibrium with C2. BF is a complement activating factor, and studies have demonstrated that at least one of the two variants associated with AMD—R32Q BF—leads to an impairment in the complement activating function of BF (Gold et al., 2006). Thus, much like impaired CFH-mediated complement inhibition confers AMD risk, decreased complement activation by BF might serve to protect against AMD risk.

Another functional polymorphism in the C3 gene, R80G, on chromosome 19p13, has been associated with AMD. The wild type variant migrates slowly on electrophoresis (C3 slow, or C3S). In contrast, the fast migrating allotype (C3F), has been reported to be strongly associated with AMD in a study from English and Scottish populations (Yates et al., 2007). C3F has in fact been associated with several diseases, including membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type II (Montes et al., 2008). This glomerulonephritis shares some similarities with AMD—namely, a role for uncontrolled alternative complement activation as well as the accumulation of complement-containing extracellular deposits. The deposits in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis are key features of the disease and are located in the glomerular basement membrane of the kidney (Finn and Mathieson, 1993; Pickering et al., 2002). A major C3-regulated factor is the complement factor I (FI). FI is involved in the degradation of the C3b component of the C3bBb complex of the alternative pathway. Variation near the FI gene on chromosome 4q25 is associated with risk of advanced AMD, although no obvious functional variation has been discovered (Fagerness et al., 2008).

These incipient studies on the role of complement in AMD have paved the way for identifying other genes in the complement pathway potentially associated with AMD. One study reported that C7 (rs2876849) is protective for AMD development in Caucasians (Dinu et al., 2007). Moreover, the SNP variant rs2511989 located in the SERPING1 gene encoding the complement component 1 (C1) inhibitor was recently reported to occur less frequently in AMD cases than in control subjects (Ennis et al., 2008). Taken together, while more extensive studies are necessary to delineate the specific roles (if any) of these complement components in AMD, the current data suggest a central role for innate immunity and inflammation in general and complement overactivation in particular for AMD pathogenesis.

3.3. Chemokines and chemokine receptors

Chemokines play a central role in recruitment of immune cells to inflamed tissues. These chemokines bind to chemokine receptors on inflammatory cells such as macrophages to promote the mobilization of these cells out of circulation and into tissues. One chemokine receptor that has generated much interest in AMD is CX3CR1. The CX3CR1 chemokine receptor is a G-coupled receptor found on a variety of inflammatory cells, including microglia, macrophages, T-cells, and astrocytes. When bound by its ligand, CX3CL1 (also known as fractalkine), CX3CR1 mediates mobilization of leukocytes to inflamed tissues and subsequent activation of these inflammatory cells (Fong et al., 1998). Both CX3CR1 and CX3CL1 are rich in the retina and brain (Combadiere et al., 1998; Foxman et al., 2002).

3.3.1. CX3CR1 SNP and AMD

CX3CR1 is encoded in chromosome 3p21.3 in human. We have reported that the V249I (valine to isoleucine at amino acid 249) and T280M (threonine to methionine at amino acid 280) CX3CR1 SNPs confer increased risk of AMD (Tuo et al., 2004). The OR (CI) of these two SNPs were 1.86 (1.04–3.31) for V249I and 1.94 (1.02–3.69) for T280M. In a French study, homozygosity for the CX3CR1 T280M allele was also reported to be associated with AMD (Combadiere et al., 2007). We have also compared expression of CX3CR1 mRNA and protein in AMD macular cells obtained from archived paraffin-embedded tissue sections (Chan et al., 2005). This previous study showed that CX3CR1 transcript and protein in the AMD maculae were undetectable or expressed at much lower levels than their SNP-type counterparts in the normal eyes. In normal eyes, macular cells from an individual bearing “at risk” allele T/M280 exhibited lower CX3CR1 transcript expression than an individual bearing “wild type or major” allele T280T. Moreover, we found lowered CX3CR1 expression in the macula compared with the perimacular retina of AMD eyes bearing T280M. In contrast, similar levels of CX3CR1 expression were detected in macular and perimacular regions of the normal subjects, which suggested that CX3CR1-mediated decreases in inflammatory cell chemokinesis might contribute to age-related changes in the macula (Chan et al., 2005; Tuo et al., 2004) (Fig. 4). These results are supported by the recent study by Combadiere and colleagues, whose immunohistochemical analysis in humans showed that CX3CR1 was expressed on all retinal microglial cells, and these cells are the only cells in the retina that express CX3CR1. Their immunohistochemical analysis of AMD cases suggest that CX3CR1-positive microglial cells accumulated subretinally in affected areas of the macula, and they may determine particular pathological conditions to stimulate AMD development (Combadiere et al., 2007).

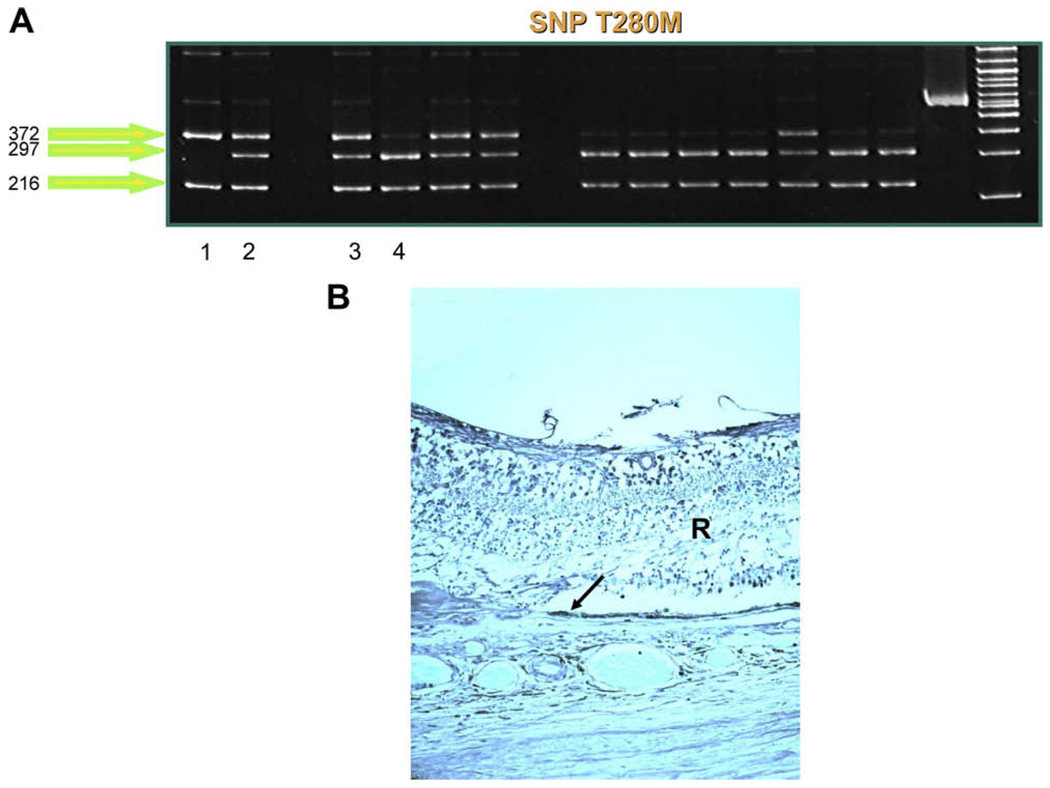

Fig. 4.

CX3CR1 in AMD eyes. (A) Different CX3CR1 SNP patterns are detected in AMD cases. Lane 1 demonstrates two bands (372, 216 bp), indicating homozygosity for the risk-conferring CX3CR1 T280M SNP. Lanes 2 and 3 reveal three bands (372, 297, 216 bp), representing heterozygous cases. Lane 4 demonstrates a wild-type (normal) case, which is indicated by two bands (297, 216 bp). (B) Low CX3CR1 expression (arrow) is observed in an AMD eye with CX3CR1 T280M.

3.3.2. Other chemokines, cytokines and toll-like receptors

The interleukin-8 (IL8) A251T genetic polymorphism located in chromosome 4q13–21 is reported to be associated with AMD, with the homozygous AA genotype (A allele) as the “at risk” factor (Goverdhan et al., 2008). The AA genotype has also been shown to induce angiogenesis in rat cornea (Koch et al., 1992). The IL8 251AA genotype is postulated to act by influencing IL8 production, or, alternatively, through linkage disequilibrium with functional variants elsewhere in the IL8 loci or in neighboring genes. In the same study, SNPs in other pro-inflammatory chemokines including interleukin-1β (IL1β) C511T, interleukin-6 (IL6) C174G and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 G1082A were analyzed and showed no significant association with AMD (Goverdhan et al., 2008). Taiwan Chinese carriers of the IL8 C781T variant, independent to the CFH Y402H variant, have also been shown to be at increased risk of developing wet AMD (Tsai et al., 2008).

The Toll-like receptor (TLR) family consists of 10 receptors that play a critical role in innate immunity. These receptors differentiate between a broad range of microbial molecules to induce an appropriate immune response by tissue and inflammatory cells. TLR4, for example, recognizes the lipopolysaccharide component of bacterial cell walls. Association with a microbial component triggers upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes such as tissue necrosis factor, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6, through the NF-kB pathway (Misch and Hawn, 2008). Moreover, TLR4 has also been implicated in photoreceptor outer segment handling and phagocytosis by RPE cells (Kindzelskii et al., 2004). A study by Zareparsi et al reported that the D299G (aspartate to glycine at amino acid 299) TLR4 (encoded in chromosome 9q32–33) polymorphism leads to increased AMD risk (OR = 2.65) (Zareparsi et al., 2005). Subsequent studies, for example by Despriet and Edwards, however, demonstrated no significant association of the D299G TLR4 SNP with AMD risk (Despriet et al., 2008; Edwards et al., 2008). Functionally, the D299G TLR4 variant has been linked to impaired LPS responsiveness in mice, which is reversible by TLR4 overexpression (Arbour et al., 2000). It is possible, then, that if TLR4 is, indeed, linked to AMD, presence of the D299G TLR4 variant leads to impaired response to and clearance of microbes, which might facilitate ongoing low-grade inflammatory state leading to pathological changes seen in AMD. Given the conflicting studies to date, however, considerable studies are necessary to clarify whether TLR4 is implicated in AMD pathogenesis.

The L412F variant of the TLR3 gene (i.e. a leucine to phenylalanine change at amino acid 412), encoded by the T allele at rs3775291 of the TLR3 gene, has been reported in three case-control cohorts to be protective against dry AMD, possibly through suppression of RPE apoptosis (Yang et al., 2008). However, other investigators have been unable to confirm this association (Edwards et al., 2008; Kaiser, 2008). After genotyping 68 SNPs across the TLR genes in a cohort of 577 subjects, with and without AMD, in two additional cohorts used for replication studies, Edwards and colleagues report that TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7 are unlikely to have major impact on overall AMD risk (Edwards et al., 2008). Further analyses of more cohorts or re-analyses of the above cohorts with absolutely normal controls could help to clarify the association of TLR with AMD (Edwards et al., 2008; Kaiser, 2008).

In general, the relationships of these SNPs with AMD are still preliminary or controversial to date and require additional studies in diverse and larger populations. If further molecular epidemiological investigations support these variants in AMD, functional studies should be performed to verify the role of their risk-conferring variants in AMD pathogenesis.

3.4. LOC387715/ARMS2 and HtrA1

A genome-wide scan and genetic linkage analysis of 70 families with AMD suggests that chromosome 10q26 may contain a common AMD gene (Majewski et al., 2003). This finding of an AMD susceptibility locus on chromosome 10q26 has been replicated by other genome-wide linkage studies (Weeks et al., 2004) and supported by a genome-scan meta-analysis (Fisher et al., 2005). Later, a focused SNP genotype study of AMD families and a case-control cohort study also found a strong association overlying three genes at 10q26. The association was strongest over two nearby genes, LOC387715/ARMS2 (age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2, or ARMS2) and a secreted heat shock serine protease (high temperature required factor A-1, HTRA1) (Jakobsdottir et al., 2005). Although there is strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) across these two genes, these two genes seem to play different putative functional roles and are expressed in different patterns in retina with or without AMD. Therefore, we discuss them separately.

3.4.1. ARMS2 SNP and AMD

The association of ARMS2 gene with AMD, especially advanced AMD, susceptibility has now been replicated in numbers of independent studies (Conley et al., 2006; Rivera et al., 2005; Ross et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2006; Seddon et al., 2007; Kanda et al., 2007). The risk-conferring ARMS2/LOC387715 SNP, A69S, is associated with AMD. Heterozygozity at the ARMS2/LOC387715 (A69A/A69S) is associated with odds ratio (OR) of 1.69–3.0 for advanced AMD, while homozygosity for the risk conferring allele (A69S/A69S) results in an OR of 2.20–12.1, after controlling for demographic and behavioral risk factors (Ross et al., 2007). Our data, including a population-based study (Wang et al., 2008), and data by Jakobsdottir and colleagues (Jakobsdottir et al., 2005) have both shown that the frequency of the ARMS2 risk allele is higher in patients with advanced AMD than in those with early or intermediate AMD. Interestingly, an even stronger effects on AMD risk has been noted in patients with both the risk-conferring ARMS2 variant and elevated serum levels of several inflammatory markers including CRP, IL-6, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (sICAM-1) (Wang et al., 2008).

More recently, Fritsche et al. showed that a deletion-insertion polymorphism (*372_815delins54), which resides within the 3′-UTR of the ARMS2 gene, also associates very significantly with AMD (Fritsche et al., 2008). In this deletion-insertion polymorphism variant, the deletion removes the polyadenylation signal sequence at position *395_400 exclusively used for the addition of a poly(A) tract 19 bp downstream. The insertion introduces a 54-bp AU-rich element, known for its properties to control mRNA decay in many transcripts that encode a wide variety of proteins involved in transient biological processes (Barreau et al., 2005; Garneau et al., 2007; Khabar, 2005). As a consequence, expression of ARMS2 in homozygous carriers of the deletion-insertion variant is absent, or at least sufficiently low to be experimentally undetectable. Most importantly, since the A69S and InDel are in 100% LD and on the same haplotype, the effects are not independent to each other.

3.4.2. ARMS2 expression

ARMS2 is highly expressed in placental tissue, but only limited biological properties have been attributed to it until recently. Kanda et al. reported that ARMS2 is localized to the ellipsoid region of the photoreceptors in retina, where most of the mitochondria are located (Kanda et al., 2007). Recently, Fritsche et al. correlated the ARMS2 SNPs to ARMS2 expression level (Fritsche et al., 2008). Immunoblot analysis in human placentas showed that ARMS2 is expressed in individuals with one or two non-risk haplotypes but not in homozygous carrier of the insertion-deletion ARMS2 risk variant. Fritsche et al. also showed that ARMS2 protein in the human retina localizes to the photoreceptor layer and that it demonstrates a minor dot-like staining in the ellipsoid region of the rod and cone inner segments, which fully co-localizes with a mitochondrial marker, anti-MTCO2, suggesting that ARMS2 is expressed in the mitochondria (Fritsche et al., 2008).

3.4.3. ARMS2 and mitochondria

Mitochondria are the major source of superoxide anion in the cell. The superoxide anion generates highly toxic hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide that damage the cell by reacting with proteins, DNA, and lipids and ultimately, by inducing cell death. Several lines of evidence indicate that mitochondria play a central role in aging and in the pathogenesis of AMD. First, studies have shown that human donor AMD eyes contain higher levels of protein adducts resulting from the oxidative modification of carbohydrates and lipids (Crabb et al., 2002; Howes et al., 2004) and higher levels of antioxidant enzymes (Decanini et al., 2007; Frank et al., 1999) compared with non-AMD eyes, which indicate that oxidative stress plays an important role in AMD. Second, converging evidence has suggested that DNA damage occurs more readily in the mitochondrial than the nuclear genome, and that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage could lead to RPE dysfunction. Blue light irradiation and treatment with hydrogen peroxide cause long-lasting mtDNA but not nuclear DNA mutations in cultured RPE cells (Ballinger et al., 1999; Godley et al., 2005). Moreover, mtDNA damage accumulates in the retina and RPE with age (Barron et al., 2001).

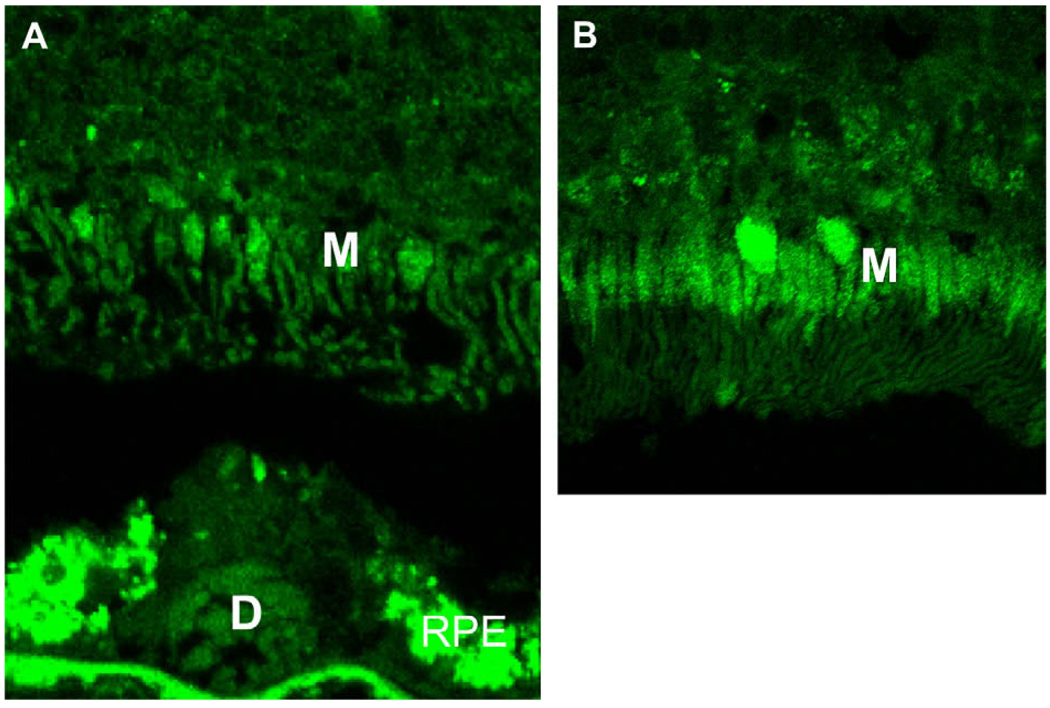

Recently, several studies offered direct evidence of mitochondrial alterations in AMD (Feher et al., 2006; Nordgaard et al., 2006, 2008). Similar to findings by Feher and colleagues (Feher et al., 2006), we have also found a drastic decrease in normal mitochondria in the photoreceptors and RPE cells of the AMD eyes as compared to that of the normal age-control eyes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Decreased mitochondria in AMD retina. The number of mitochondria (M) is much lower in the inner segment of photoreceptors of the AMD eye (A) as compared with a normal age-control eye (B). Accumulation of lipofuscin is known to autofluoresce (in yellowish green color) in the RPE and drusen of the AMD eye (green: immunofluorescence staining with anti-human COV IV, a specific marker of mitochondria).

3.4.4. HtrA1 SNP and AMD

The HtrA1 gene is located on chromosome 10q26.3, extremely close to the locus at ARMS2, 10q26.13. Indeed, as described above, these two genes are in strong linkage disequilibrium. To date, four significant SNPs have been reported in the promoter and the first exon of HtrA1: rs11200638 (G625A), rs2672598 (T487C), rs1049331 (C102T, A34A), and rs2293870 (G108T, G36G). Several studies have shown that rs11200638 in the promoter region is the most well-documented, statistically significant AMD-associated SNP with a high OR of 1.60–2.61 and 6.56–10.0 in heterozygous and homozygous individuals (Caucasians, Chinese and Japanese), respectively (Cameron et al., 2007; Deangelis et al., 2008; Dewan et al., 2006; Mori et al., 2007; Tam et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2006). Mori et al. showed that presence of the A allele at rs11200638, which is the risk allele, was associated in subtype analyses with wet AMD (Mori et al., 2007). Later, Cameron et al. found that rs11200638 was also significantly associated with geographic atrophy (Cameron et al., 2007). By examining four cohort studies, we have also confirmed this association with ORs of 2.17 and 2.97 for dry and wet AMD, respectively (Tuo et al., 2008). In addition, recent studies have shown that there is an observable increase in population attributable risk (about 5.5-fold increase) by the joint effect of smoking and the HtaA1 risk allele, indicating that smokers homozygous for the risk allele had a substantially higher risk of developing wet AMD than non-smokers with the risk allele (Tam et al., 2008). This finding is in accordance with a previous study by Schmidt and colleagues where smoking significantly increased the risk of AMD in patients with the A69S variant in LOC387715 (Schmidt et al., 2006). In contrast, Deangelis et al. reported that although the HtrA1 SNP was significantly associated with wet AMD, no interaction was found between this SNP and smoking in a phenotypically well-defined cohort of 268 subjects including 134 extremely discordant sibpairs (Deangelis et al., 2008).

3.4.5. HtrA1 expression

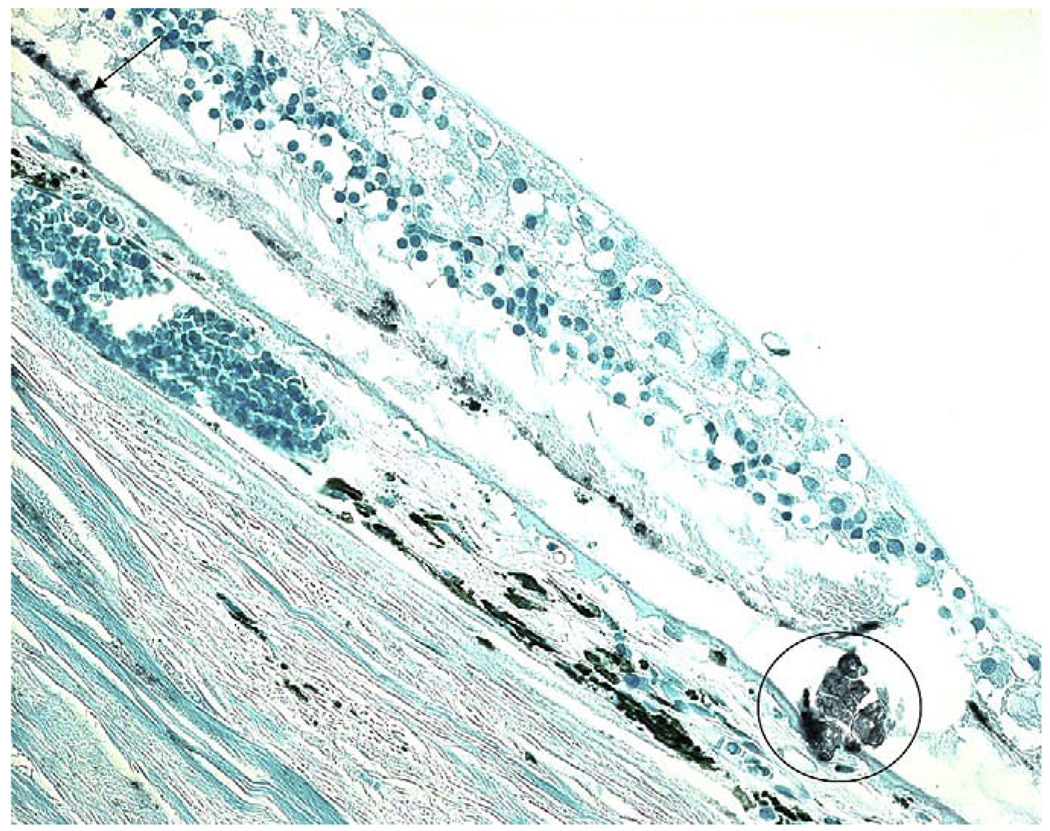

HtrA1 is a stress-inducible member of a family of heat shock serine proteases, which is involved in the modulation of various malignancies and diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and osteoarthritis (Grau et al., 2006). As rs11200638 is located within a CpG island of the proximal promoter, 512 bp upstream of the HtrA1 transcription start site, the risk allele “A” of HtrA1 SNP was shown to enhance HtrA1 transcription in vitro in RPE cell lines (Dewan et al., 2006). In the same study, individuals homozygous for the risk allele (genotype AA) expressed higher levels of HtrA1 in their circulating lymphocytes in vivo, compared with individuals homozygous for the non-risk variant (genotype GG). In vivo HtrA1 is expressed in a variety of human tissues and cells, including the RPE and vascular endothelium (Chan et al., 2007). Elevated expression of HtrA1 mRNA and/or protein in the drusen and CNV components in AMD patients carrying the AA risk genotype has been reported in several studies (Cameron et al., 2007; Chan et al., 2007; Tuo et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2006) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

HtrA1 expression in AMD eye. Positive immunoreactivity for HtrA1 is observed in the AMD lesion (circle) and residual RPE cells (arrow).

Preliminary evidence suggests that HtrA1 plays dual functions in extracellular protein degradation and in cellular growth or survival. In chronic inflammatory conditions, extracellular protease activities of HtrA1 may favor neovascularization by enhancing degradation of extracellular matrix components through increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases (Grau et al., 2006), or by binding to transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, an angiogenic factor whose expression has been geographically and temporally linked to CNV (Ogata et al., 1997; Oka et al., 2004). HtrA1 is also a secretory protein and an inhibitor of TGF-β family member (Oka et al., 2004). TGF-β controls a plethora of neural and glial function throughout life. Blockage of the proteolytic activity of HtrA1 leads to a restoration of TGF-β signaling and subsequent neuronal death, suggesting that HtrA1 could play a critical role in controlling TGF-β dependent neuronal survival (Launay et al., 2008). TGFβ also is a potent inhibitor for immune response (Lehner, 2008; Wahl, 2007).

Overall, the biological functions and potential role of the HtrA1 promoter SNP in AMD remain exploratory and speculative. Further studies on the possible mechanisms of this susceptibility gene may provide information on variable phenotypes, new preventive strategies, and therapeutic options for AMD.

3.4.6. ARMS2/HtrA1

Much debate exists as to whether ARMS2, HtrA1, or both are responsible for the AMD susceptibility from chromosome 10q26. Recently Kanda et al. reported that ARMS2 (T allele at rs10490924, A69S), rather than HtrA1, to be truly associated with AMD (Kanda et al., 2007). Their data show that the A69S ARMS2 SNP is best explained the AMD susceptibility associated with the AMD locus at chromosome 10q26. Moreover, in a Chinese cohort study evaluating patients with wet AMD and control subjects, ARMS2 was slightly more associated with AMD than HtrA1 SNP, and they were in the same linkage disequilibrium block (Dewan et al., 2006). Another report also supports the notion that the ARMS2 variant is an independent risk factor for neovascular AMD (Shuler et al., 2008).

Although the exact biological roles of both the ARMS2 and HtrA1 genes in humans are unclear, SNP analyses have confirmed their association with AMD. It is possible that these SNPs, which contribute to AMD development and are located on one haplotype, may act independently or interact with other genes related to AMD, not only on genetic but also protein levels. It is also possible that ARMS2 and its pathway may be linked to mitochondrial oxidative stress, while HtrA1 and its pathway may be involved in the regulation of cell survival via chaperon/proteases (Clausen et al., 2002), and the inhibition of immune response via TGF-β (Launay et al., 2008).

3.5. Apolipoprotein E (ApoE)

Apo-E is a structural component of plasma chylomicrons, very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), and a subclass of high-density lipoproteins (HDL), and is synthesized in many tissues including the spleen, kidneys, lungs, adrenal glands, liver, and brain (Shanmugaratnam et al., 1997). The primary physiological role of ApoE is to facilitate the binding of LDL to LDL receptors on cellular membranes, thereby regulating the uptake of cholesterol required by cells. For instance, when large amounts of lipids are released from degenerating neuronal cellular membranes, the lipid materials can stimulate the astrocytes to synthesize ApoE, which binds these excess lipids and redistributes them for reutilization in cell membrane biosynthesis. Based upon this fact, Klaver et al. have speculated that an active biosynthesis of ApoE is required to support the high rate of photoreceptor renewal in the macular region (Klaver et al., 1998).

3.5.1. ApoE SNP and AMD

The ApoE gene is located on chromosome 19q13.2 and is polymorphic, with three common isoforms: E2, E3, and E4. These three isoforms are coded by three different alleles: the ancestral E3 and the SNPs E2 and E4 (Schmidt et al., 2002). ApoE polymorphisms have already been linked to several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease, and prion diseases (Krasnianski et al., 2008; Tzourio et al., 2008). The Rotterdam Study in the Netherlands reported a protective role for the ApoE4 SNP (OR = 0.45) and a slight risk-conferring role for the ApoE2 SNP (OR = 1.5) (Klaver et al., 1998). Based on the role of ApoE in recycling of cholesterol and lipids for cell-membrane biosynthesis after neuronal injury, these polymorphisms have been speculated to impact retinal membrane renewal and affect macular integrity. Several studies later confirmed a role for ApoE SNP in AMD (Baird et al., 2006; Jun et al., 2005; Kovacs et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2002; Souied et al., 1998; Zareparsi et al., 2004), while others found no effect (Kaur et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2005; Schultz et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2006). We have also found the association between ApoE112R (E4) and a decreased risk of AMD development, and the underlying mechanisms might involve differential regulation of both CCL2 and VEGF by the ApoE isoforms (Bojanowski et al., 2006). However, a large, population-based, cross-sectional study (n = 10,139) using participants from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study found no association between AMD and any of the ApoE alleles in Australia (Kaur et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2005; Schultz et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2006).

3.5.2. ApoE expression

In AMD patients, the presence of ApoE has been illustrated in drusen (Shanmugaratnam et al., 1997). Ishida et al. also showed that AMD macula exhibit increase ApoE staining in drusen and basal laminar deposits. They have further demonstrated that RPE cells secrete ApoE in response to a variety of hormones, and that the secreted ApoE is associated with HDL. These findings suggest a possible role for ApoE in AMD pathology via retinal lipid trafficking (Ishida et al., 2004). Therefore, aging or disease-related disruption of normal ApoE function may result in the accumulation of lipoproteins between RPE and Bruch’s membrane, which is consistent with lipid deposits in drusen. Indeed, the lipid deposits of drusen are often composed of cholesteryl esters and unsaturated fatty acids. Accumulation of drusen-associated lipid due to the impaired ApoE function could potentially affect the functional integrity of Bruch’s membrane. Furthermore, the ApoE profile might influence the transport, capture, and stabilization of other key molecules, such as lutein and zeaxanthin, in the macula to ultimately accelerate the aging process and AMD development (Ong et al., 2001).

3.6. VEGF

It is well established that the formation of blood vessels occurs by angiogenesis and that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a key molecule in promoting angiogenesis (Ferrara et al., 2003). VEGF can potentially induce vascular leakage and inflammation by triggering the increased production and permeability of capillary endothelial cells. The VEGF family currently includes VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D, -E, -F and placenta growth factor (PlGF), that bind in a distinct pattern to three structurally related receptor tyrosine kinases, denoted VEGF receptor-1, -2, and -3. Increased expression of VEGF-A in the RPE and in the outer nuclear layer is reported in post-mortem maculae obtained from individuals with AMD (Kliffen et al., 1997). VEGF plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of neovascular AMD, and recently, therapies targeting VEGF have shown promising results of significant improvement of central vision and reduction of CNV (Wylegala and Teper, 2007).

3.6.1. VEGF-A SNP and AMD

The VEGF-A gene is located on human chromosome 6p21 and is highly polymorphic. At least six polymorphisms in the VEGF-A gene are detected to alter the levels of VEGF transcript expression: C2578A, G1154A, and T460C in the promoter region; C405G and C674T in the 5′-untranslated region; and C936T in the 3′-untranslated region (Churchill et al., 2006).

Several studies have documented a significant association between variants in the VEGF-A gene and the risk of AMD. Neovascular AMD was found to be associated with the rs2010963 (G634C) VEGF-A SNP in a case-control cohort, and in a family cohort with two intronic VEGF-A SNPs (rs833070 and rs3025030) (Haines et al., 2006). Another study, which involved 45 patients with neovascular disease, identified a haplotypic association in both the promoter and an intronic region of the VEGF gene (Churchill et al., 2006). Lin et al. genotyped five VEGF-A polymorphisms: C2578A, T460C, C405G, C674T, and C936T in a Chinese population study and found that only the VEGF C936T SNP was significantly increased in wet AMD (Lin et al., 2008). However, Richardson et al. (2007) provided a thorough tag-SNP based examination and found little evidence to support an association of the VEGF-A gene with AMD. Several other reports also showed no association between wet AMD and the VEGF gene (de Jong et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2007). These conflicting data could result from differences of the ethnicities studied, study designs, and statistical analyses.

3.6.2. VEGF-A SNP genotype and therapeutic responses

Currently several new therapeutic options targeting VEGF are available for wet AMD (Rosenfeld et al., 2006). Pegaptanib (macugen), an oligonucleotide aptamer that targets the VEGF165 isoform, and ranibizumab (Lucentis) and bevacizumab (Avastin), both monoclonal antibodies against VEGF-A, are currently employed in AMD therapy (Ferrara et al., 2006; Kaiser, 2006). Although VEGF SNPs may not be strongly associated with AMD, they might nevertheless contribute to the effectiveness of the anti-VEFG treatment. If so, pharmacogenetics studies may help us to determine which patients are likely to benefit from such anti-VEGF therapies.

3.7. ERCC6

ERCC6, a DNA repair gene, is located at chromosome 10q11. This gene is involved in excision repair of DNA and is responsible for Cockayne syndrome. The ERCC6 SNP C6530G is in the 5′ flanking region. One study has demonstrated that the ERCC6 C6530G SNP is modestly associated with AMD susceptibility, its interaction with a SNP (rs380390) in the CFH intron is highly associated with AMD (Tuo et al., 2006). A disease OR of 23 was conferred by homozygosity for risk alleles at both ERCC6 and CFH compared with homozygosity for non-risk alleles.

Enhanced ERCC6 expression is observed in lymphocytes from healthy donors bearing ERCC6 C6530G alleles (Tuo et al., 2006). The strong AMD predisposition conferred by the ERCC6 and CFH SNPs may result from biological epistasis, because ERCC6 functions in universal transcription as a component of RNA pol I transcription complex. Intense immunoreactivity of ERCC6 is observed in AMD eyes from ERCC6 C6530G carriers. Overexpression of a single element in an enzyme complex can adversely impact complex functionality (Rinne et al., 2004). These data suggest that DNA repair mechanisms may play a role in AMD pathogenesis.

3.8. ATP-binding cassette sub-family, member 4 (ABCA4)

Recessively inherited Stargardt’s disease is associated with mutations in a ATP-binding cassette sub-family, member 4 (ABCA4) gene on chromosome 1p21 that encodes rim protein, an ATP-binding transporter in the rims of photoreceptor outer segment disks (Azarian and Travis, 1997). Given clinical similarities between Stargardt’s disease and AMD, such as central vision loss, progression RPE and photoreceptor atrophy, and the presence of retinal deposits, Allikmets and his colleagues investigated 167 AMD patients to demonstrate whether mutations in the ABCA4 gene might also contribute to AMD pathogenesis. They identified variants in one allele of the gene in 16% of the AMD patients (Allikmets, 1997; Allikmets et al., 1997). Clinically, late onset Stargardt cases can be misdiagnosed as AMD, especially when basing diagnosis solely on photographic grading. It is possible that some of the association seen in the Allikmets et al. (1997) study reflects misdiagnosis of Stargardt’s disease, which has previously been shown to be associated with ABCA4, as AMD. Moreover, multiple subsequent studies showed little or no relation of ABCA4 mutations with AMD (Bojanowski et al., 2005; De La Paz et al., 1999; Souied et al., 2000; Stone et al., 1998). Without doubt, further studies are required to clarify whether the ABCA4 gene influences AMD development.

4. Involvement of inflammatory cells

AMD is a multifactorial disease that affects primarily the photoreceptors and RPE cells. The RPE cell is a specialized neural cell originated from neuroectoderm that provides metabolic support mainly to photoreceptor cells and is close to the inner thin basal membrane of the Bruch’s membrane, which interposed between the RPE and choriocapillaries. In normal eye physiology, the cells of the RPE are essential for the maintenance of retinal homeostasis. Both photoreceptors and RPE cells exhibit age-related changes such as the size and shape of the cells, their nuclei and the pigment granules for RPE cells, especially on the molecular level, as well as AMD-specific changes.

There is ample evidence that inflammation plays an important role in both dry and wet AMD. Recently, Nussenblatt and Ferris posited the importance of the Downregulatory Immune Environment (DIE) in the eye (Nussenblatt and Ferris, 2007). This theory posits that the natural environment of the eye is designed to downregulate inflammation, thereby maintaining equilibrium in the eye. Therefore, any defect in the eye can disrupt the DIE, resulting in an overexuberant immune response in the eye (Nussenblatt and Ferris, 2007). Indeed, the RPE cell is one of many systems that downregulate the immune response in the eye, and thus the pathway between RPE damage and ocular inflammation is likely a two way street whereby RPE damage potentiates inflammation, which further worsens RPE degeneration.

4.1. Macrophages

While AMD is not a classic inflammatory disease like uveitis; inflammatory cells, in particular the macrophages, have been histologically demonstrated near AMD lesions, including in areas of Bruch membrane breakdown, RPE atrophy, and choroidal neovascularization (Coleman et al., 2008; Dastgheib and Green, 1994; Green, 1999; Grossniklaus et al., 2002; Lopez et al., 1993; Penfold et al., 2001). Moreover, macrophages can secrete various chemokines, which are implicated in AMD models of Ccl2−/− and Ccr2−/− murine models of AMD (see Section 5 below).

4.1.1. Macrophages in CNV

Several groups have demonstrated the presence of macrophages at neovascular membranes in wet AMD (Dastgheib and Green, 1994; Grossniklaus et al., 2002; Penfold et al., 2001). Moreover, macrophages in CNV lesions have been shown to express proangiogenic factors such as VEGF and tissue factor (Csaky et al., 2004; Grossniklaus et al., 2002).

While the presence of macrophages at CNV lesions is largely recognized, the role of these macrophages presents some controversy as to whether these macrophages serve an adaptive role to combat CNV or a causative role in inducing CNV. Two groups have investigated the role of macrophages in AMD using dichloromethylene diphosphonate (Cl2MD)-containing liposomes. When Cl2MD-containing liposomes are ingested by macrophages, the toxic Cl2MD enzyme is released, resulting in macrophage death. Espinosa-Heidmann et al. (2003) and Sakurai et al. (2003) and their colleagues showed that when administered to mice, these liposomes markedly impaired macrophage recruitment to areas of laser retinal injury. Decreased macrophage accumulation at laser injury sites correlated with less severe laser-induced CNV, as determined by fluoroscein angiography and histology.

On the other hand, Apte and colleagues, using a model of interleukin-10 (IL-10) deficient mice, found that macrophages play a protective role in CNV (Apte et al., 2006). They demonstrated that IL-10−/− mice exhibit increased recruitment of macrophages, resulting in decreased susceptibility to laser-induced CNV, suggesting a beneficial anti-CNV role for macrophages. This effect was blocked by inhibition of macrophage entry by anti-CD11b antibodies, anti-F4/80 antibodies, or IL-10 supplementation. They also showed that IL-10 transgenic mice had decreased macrophage recruitment to the retina and developed more severe laser-induced CNV lesions. Furthermore, macrophages were capable of killing CD95+ cells and interacting with CD95L to mediate the development of laser-induced CNV. To address the discrepancies between their findings and earlier work by Sakurai and Espinosa-Heidmann, Apte and colleagues reported that the Cl2MD-containing liposomes could penetrate CNV endothelial cells and directly damage CNV endothelium. They reported that the decreased CNV reported by Espinosa-Heidmann et al. and Sakurai et al. might therefore be secondary to the direct injury to CNV endothelium, rather than the depletion of macrophages (Apte et al., 2006).

4.1.2. A dual role for macrophages in AMD

Another plausible explanation for these seemingly contradictory findings is that macrophages comprise a heterogeneous group with a spectrum of phenotypes and activities (Mantovani et al., 2004). There are two subtypes of macrophages: the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, and the relatively anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, which function scavenging and tissue remodeling. Therefore, it is possible that M2 macrophages in early stages perform the beneficial, long-term housekeeping role of scavenging deposits such as cleaning drusen. In contrast, M1 macrophages might induce and compound the inflammatory responses to the retinal injury by the laser, accelerating CNV development (Mantovani et al., 2004). Further investigation is warranted to determine whether macrophage polarization plays a role in AMD and CNV pathogenesis, and if so, to clarify the specific activities of these macrophage subtypes at various stages of AMD.

4.2. Microglia

Microglia are the resident immune cells in the retina required for neuronal homeostasis and innate immune defense (Langmann, 2007). They enter the retina during embryological development and are activated by retinal injury and degeneration, leading to the transformation of quiescent stellate-shaped microglia into large ameboid bodies. These activated microglia proliferate, migrate to areas of injury, phagocytize debris, and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as neurotoxins (Langmann, 2007). Indeed, histological analysis of AMD retinas has depicted the presence of many activated microglia in the macular lesions (Gupta et al., 2003).

As described above, the CX3CR1 chemokine receptor found on microglia has been shown to harbor SNPs (T280M and V249I) that have been associated with increased risk of AMD in some reports (Chan et al., 2005; Tuo et al., 2004). Importantly, more studies that replicate these findings are necessary to confirm the association between CX3CR1 and AMD.

The CX3CR1 SNP is associated with impaired microglial chemotaxis (Combadiere et al., 2007). Since microglia are already present in the retina since embryological development and do not chemotactically enter the retina, these SNPs might lead to impaired microglial migration or egress from the retina, resulting in accumulation of microglia. These accrued microglia might cause direct damage to the photoreceptors. This is supported by at least one study demonstrating photoreceptor cell injury after administration of activated microglia to healthy photoreceptors (Roque et al., 1999). The findings from the Cx3cr1−/− murine model of AMD developed by Combadiere et al. also show that microglia play an important role in subretinal lesions (Combadiere et al., 2007), which we have discussed in further detail above.

5. Animal models of AMD

5.1. Introduction

Many efforts have been made to establish animal models that mimic human AMD. The development of a suitable model facilitates the identification of risk factors for disease development, elucidates fundamental molecular mechanisms underlying disease progression, and provides valuable guidance as to whether or not a particular treatment is a potentially safe and effective option for humans. The mouse is a genetically well-defined species, and the techniques for engineering the mouse genome are well developed and fairly reliable. Moreover, the methods for evaluation of retinal lesions in mice are well documented and applicable. The main drawback of using mice to study AMD is that the mouse retina has no macula. However, murine retinal degenerative diseases can still provide relevant information that will help our understanding of human AMD. Most of the retinal degeneration genes found first in mouse have been linked to a corresponding human retinal disease, and thus we know that identifying disease-related genes in mice is both relevant and important (Rakoczy et al., 2006). This section focuses on genetic-engineered mouse AMD models, which represent different spectrums of human AMD pathology and involve the molecules that we have discussed in the above text.

5.2. Chemokine model

5.2.1. Ccl2−/− and Ccr2−/− murine models

CCR2 is a chemokine receptor on macrophages that binds MCP-1/CCL2 to mediate adhesion of inflammatory cells to the vasculature, as well as their subsequent extravasation into tissues. CCL2 or CCR2 deficiency leads to impaired accumulation of macrophages at sites of inflammation (Kuziel et al., 1997; Lu et al., 1998).

Indeed, a murine model of Ccl2 or Ccr2 deficiency leads to decreased accumulation of macrophages in the retina, as well as key features of AMD including drusen (Ambati et al., 2003). Ambati and colleagues demonstrated that the Ccl2- and Ccr2 knockout mice (Ccl2−/− and Ccr2−/−) exhibit AMD-like drusen visible fundoscopically by 9 months of age. They also show histological and ultrastructural features of AMD including lipofuscin accumulation, thickening of Bruch membrane, and increased melanosomes in the RPE. Biochemical analysis revealed that A2E levels are similarly increased in these mice. Eventually, by 16–18 months of age, Ccl2−/− and Ccr2−/− mice also develop geographic RPE atrophy and choroidal neovascularization.

In light of these findings, Ambati and colleagues hypothesized that impaired chemotaxis of macrophages to the retina impedes macrophage-mediated clearance of drusen components, leading to the generation of drusen deposits. They demonstrated that C5, IgG, and advanced glycosylation products, three components of drusen, normally upregulate Ccr2 expression in RPE cells and choroidal endothelial cells, presumably to attract macrophages. They further showed that macrophages are capable of adhering to IgG and C5 to promote their clearance. As expected, impaired macrophage recruitment in Ccl2 and Ccr2 deficient mice was associated with an accumulation of C5, IgG, and other drusen constituents within the retina.

In short, the Ccl2−/− and Ccr2−/− murine models of AMD suggest a protective role for macrophages in AMD pathogenesis—clearance of deposits. The pathological features of this model include CNV. This is in stark contrast to a report by Tsutsumi et al. demonstrating that decreased macrophage influx after laser injury to Ccl2−/− mice is associated with reduced laser-induced CNV (Tsutsumi et al., 2003). These studies might be reconciled by the argument that laser-induced CNV, an acute injury, occurs by a different mechanism than CNV associated with age-related degenerative changes in the retina. Perhaps in the early stage of laser-induced CNV there is influx of inflammatory cells—perhaps M1 macrophages, if the macrophage polarization hypothesis described above holds true—that lead to cell injury and secretion of proangiogenic factors. In contrast, in the absence of such acute injury, M2 macrophages may play a housekeeping role, promoting clearance of deposits. Over time, failure of macrophage entry or function in the retina might lead to accumulation of deposits and drusen, which creates a nidus of low-grade inflammation, resulting in the tissue damage and eventually, CNV.

5.2.2. Cx3Cr−/− murine model

Combadiere et al. recently reported a new Cx3cr1−/− murine model of AMD. Cx3cr1−/− mice demonstrated retinal degeneration and drusen-like deposits, which contained bloated accumulated microglia capable of phagocytosing outer segments of photoreceptor cells in 18 months and older mice. Moreover, Cx3cr1−/− mice exhibited increased microglial accumulation after laser-injury, as well as worsened laser-induced CNV and retinal degeneration. Combadiere and colleagues hypothesized that Cx3cr1 deficiency led to impaired microglial egress from the retina, facilitating their accumulation there, where they comprised drusen-like deposits and perhaps participated in retinal degeneration and CNV. The group pointed to the physical similarities between bloated microglial cells and drusen deposits, presence of organelles in drusen, and the fact that microglial cells can express some of the components commonly identified in drusen as evidence that drusen in AMD might involve, at least in part, accumulated microglial cells (Combadiere et al., 2007). The notion that microglia contribute to drusen-like deposits is further strengthened by another study demonstrating that increasing fundus autofluorescence seen in aging wild-type mice consists of perivascular and subretinal microglia, which might also contain lipofuscin granules (Xu et al., 2008). Moreover, as mentioned above, in vitro studies have demonstrated that activated microglia are capable of directly injuring photoreceptor cells (Roque et al., 1999). CX3CR1 positive cells in drusen and near CNV membranes are microglial cells in human AMD eyes (Combadiere et al., 2007). Taken together, these studies suggest a potential role for microglia accumulation in the inflammatory cascade associated with AMD.

5.2.3. Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− murine model

Animal models based upon Ccl2 and Cx3cr1 knockout have lent strength to this hypothesis and provided some insights into the potential inflammatory mechanisms underlying AMD pathogenesis. We investigated whether combining Ccl2 knockout, which has been shown to lead to AMD phenotype (described above), with Cx3cr1 knockout might lead to a novel murine model of AMD with earlier onset and higher penetration. We found that Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− mice exhibited, at an early age of 4–6 weeks, fundoscopically visible drusen-like lesions, as well as histological signs of AMD such as thickening of Bruch’s membrane, drusen, local RPE hypopigmentation and degeneration, and photoreceptor disorganization and atrophy, as well as CNV in some mice. These mice also exhibited ultrastructural signs of AMD such as accumulation of lipofuscin granules, as well as increased the N-retinylidene–N-retinylethanolamine (A2E) accumulation on biochemical analysis (Chan et al., 2008; Tuo et al., 2007).

Given the central role of inflammatory processes in AMD, we recently characterized the immune status of the Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− mice. Compared to wild-type mice, Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− mice exhibited increased complement C3 and CD46. Analysis of C3d expression by immunoreactivity revealed that this increase was especially notable in Bruch’s membrane, drusen-like lesions, photoreceptors, RPE, and choroidal capillaries (Ross et al., 2008). These findings are consistent with findings in drusen of humans with AMD (Hageman et al., 2005), as well as the critical role in AMD of complement overactivity, which has been discussed above. Macrophage and microglial accumulation was also increased relative to wild-type in Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− mice, as well as in Cx3cr1−/− mice, though to a lesser degree (Ross et al., 2008). Given prior reports of increased anti-retinal antibodies in patients with AMD (Cherepanoff et al., 2006; Joachim et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2005), we also investigated whether our mouse model possesses such antibodies. Incubation of normal retinal sections with serum from Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− also demonstrated the presence of anti-retinal antibodies in the mouse model. In contrast, minimal anti-retinal auto-antibody effect was noted in wild-type mice (Ross et al., 2008). These findings highlight that the Ccl2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− murine model of AMD is a robust one with several immunological features also documented in human AMD and supported by studies in other in vivo models of AMD. They also strengthen the argument for a critical inflammatory component to AMD pathogenesis.

5.3. Cfh−/− murine model

As discussed above, CFH polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to AMD in more than half of affected individuals. To further investigate the role of CFH in AMD pathogenesis, Coffey et al. reported visual and retinal findings in mice deficient in cfh. At age 2 years, cfh−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced visual acuity and rod response amplitudes on electroretinography as compared with age-matched control mice (Coffey et al., 2007). These mice also demonstrated increased autofluorescence, accumulation of C3, and disorganization of photoreceptor outer segments in the retina, as well as thinning of Bruch’s membrane and increased RPE organelles. Funduscopic examination and vasculature, however, appears normal in the cfh−/− mice. Coffey et al. hypothesized that a major difference between the cfh polymorphisms associated with human AMD and homozygous deficiency of CFH is that in the latter, plasma C3 levels are markedly reduced, while in the former, they are normal. Secondary C3 deficiency may critically influence the ocular phenotypes in the cfh−/− mice.

5.4. ApoE-based murine model

As discussed above, prior studies have suggested a probable association between ApoE polymorphisms and AMD. To investigate the role of ApoE in AMD pathogenesis, Malek and colleagues generated mice transgenic for each of the human ApoE allelesd—E2, E3, and E4 (Malek et al., 2005). They found that diet withstanding, ApoE status alone affected retinal changes during aging only minimally. In contrast, both ApoE2 and ApoE4 transgenic mice developed extensive retinal, RPE, and choroidal degeneration after a high fat cholesterol rich (HF-CR) diet. Aged ApoE4 mice on this diet exhibited several features of human AMD, including drusen, thickening of Bruch’s membrane, geographic RPE atrophy, and CNV. This model is in fact an improvement upon the prior ApoE-Leiden plus high fat diet model, which demonstrated only basal laminar deposits in Bruch’s membrane. Moreover, CNV in aged ApoE4 mice on the HF-CR diet contained amyloid β deposits, as well as VEGF and other factors also seen in human AMD and CNV. Malek and colleagues hypothesized that these effects might be due to the impaired cholesterol clearance and anti-oxidative properties of ApoE4, compared to ApoE3, which have been demonstrated previously. The findings from this study are somewhat contrary to several prior epidemiological studies that demonstrated a protective, rather than risk-conferring, role for the ApoE4 variant. Malek and colleagues addressed this concern by citing potential differences between human and mouse physiology, the homozygosity of their model versus the relative abundance of heterozygotes in the human epidemiological studies, as well as the important additional factor of diet included in the mouse model.

Most importantly, the ApoE-based murine model of AMD highlights the potential role for cholesterol metabolism in AMD pathogenesis and further emphasized the need to clarify the role of ApoE variants in human AMD. The role of cholesterol metabolism in AMD has been further supported by recent studies demonstrating that, in contrast to wild-type eyes, mice expressing ApoE2 exhibited signs of lipid accumulation in the RPE and Bruch’s membrane (Lee et al., 2007). This effect was even more pronounced in ApoE2 transgenic mice fed with a high fat diet. Moreover, the eyes of ApoE2 transgenic mice also expressed higher levels of the proangiogenic factor VEGF but lower levels of anti-angiogenic factor pigment epithelium derived factor (PEDF).

5.5. Abcr−/− murine model

As discussed above, polymorphisms in the ABCA4 gene might contribute to AMD pathogenesis, and recent studies in an abcr (abca4) knockout mouse (Abcr−/−) highlight potential mechanisms underlying maculopathy in patients with putative risk-conferring ABCA4 polymorphisms and perhaps even AMD in general. Abcr−/− mice demonstrate decreased dark adaptation, increased all-trans-retinaldehyde after light exposure, increased phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) in outer segments, accumulation of N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine, the conjugate of all-trans retinaldehyde and PE in photoreceptors, and deposition of A2E fluorophore, a major component of lipofuscin, in the RPE (Weng et al., 1999). Based on these findings, Weng et al. hypothesized that rim protein encoded by ABCA4 acts as a flippase for N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine (N-retinylidene-PE). By promoting the transfer of all-trans retinal-containing N-retinylidene-PE from the disk interior to the cytoplasmic surface, rim protein might facilitate the recovery of rod sensitivity after light exposure, which usually involves rhodopsin regeneration accompanied by disappearance of all-trans retinaldehyde. Moreover, impaired flippase activity explains the observed accumulation in the RPE of abcr−/− mice of protonated N-retinylidene-PE and its byproduct A2E, the major fluorophore of pathological lipofuscin in retinal degenerative diseases. These processes might therefore contribute to impaired RPE function and subsequent RPE and photoreceptor degeneration (Weng et al., 1999). In addition to photoreceptor degeneration and lipofuscin accumulation, this model also demonstrates decreased recovery of rod cell sensitivity after light exposure (Midena et al., 1997; Weng et al., 1999). Ultrastructural analysis revealed abnormal basal RPE with small irregular dense bodies in both abcr−/− and abcr+/− mice, but no drusen formation (Mata et al., 2001).

6. Summary