Abstract

During human prostate cancer progression, the integrin α6β1 (laminin receptor) is expressed on the cancer cell surface during invasion and in lymph node metastases. We previously identified a novel structural variant of the α6 integrin called α6p. This variant was produced on the cell surface and was missing the β-barrel extracellular domain. Using several different concentrations of amiloride, aminobenzamidine and PAI-1 and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) function-blocking antibody (3689), we showed that uPA, acting as a protease, is responsible for production of α6p. We also showed that addition of uPA in the culture media of cells that do not produce α6p, resulted in a dose-dependent α6p production. In contrast, the addition of uPA did not result in the cleavage of other integrins. Using α2-antiplasmin and plasmin depleted media, we observed that uPA cleaves the α6 integrin directly. Further, 12-o-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) induced the production of α6p, and this induction was abolished by PAI-1 but not α2-antiplasmin. Finally, the α6p integrin variant was detected in invasive human prostate carcinoma tissue indicating that this is not a tissue culture phenomenon. These data, taken together, suggest that this is a novel function of uPA, that is, to remove the β-barrel ligand-binding domain of the integrin while preserving its heterodimer association.

Keywords: Integrin, Urokinase, Prostate cancer

Introduction

Integrins are heterodimeric proteins with α and β subunits, and each αβ combination has its own binding specificity and signaling properties [1,2]. Integrins recognize several extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and sense the extracellular matrix environment [1,2]. They are involved in many processes including cell migration, differentiation, blood clotting, tissue organization, and cell growth. Integrins generally contain a large extracellular domain (α subunit approximately 1000 residues, and β subunit, approximately 750 residues), a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain (approximately 50 residues or less) with the exception of β4, whose cytoplasmic domain is large (more than 1000 residues) [3,4].

The structure of the extracellular segment of the alpha subunit has been determined using protein crystals of a soluble αvβ3 integrin fragment [5]. The NH2 terminal end of the alpha integrin subunit contains a seven-bladed β-propeller structure followed by a tail region composed of three β-sandwiched domains: an Ig-like “thigh” domain and two very similar domains that form the “calf” module [6]. The tail region can fold back at approximately 135° angle forming a V-shaped structure with a “genu” between the thigh domain and the calf module [6]. The profound bending suggests that a highly flexible site, the genu, exists in the integrin alpha subunit and results in a flexible 700 Å accessible surface region [6].

We have previously identified a structural variant of the α6 integrin called α6p that is missing the extracellular β-propellar domain associated with ligand binding [7]. Integrin α6p is a 70-kDa form, and mass spectrometry analysis showed that the NH2 terminal end of the molecule contains at least amino acids starting at arginine 595 [7]. The analysis also showed that the rest of the carboxy terminus of α6p was identical with the full-length α6 integrin [7]. Using a multiple sequence alignment tool, this position in α6 integrin lies within an accessible loop described for the αV integrin subunit [5]. The α6p variant, produced while on the cell surface, remains paired with either the β1 or β4 subunit and has a 3-fold increase in biological half-life as compared to the full-length α6 integrin. [8]. The extracellular surface expression of the α6 integrin before cleavage suggested that an extracellular protease mediated the conversion.

Urokinase-type plasminogen Activator (uPA) is a secreted 54-kDa serine protease which cleaves plasminogen as a primary substrate [9]. In addition, uPA has been shown to catalyze the proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin [10], hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) [11], and macrophage-stimulating protein (MSP) [12]. There is no universal consensus site for uPA cleavage of its substrates. The enzyme uPA is synthesized and released by cells as an inactive, single chain proenzyme. When pro-uPA binds to the uPA-receptor (uPAR), it is cleaved primarily by plasmin, but also by kallikrein, blood coagulation factor XIIa, and cathepsin B [13], into its two-chain active form [14–16]. The binding of pro-uPA to the uPAR in effect targets the enzyme activity to areas of the cell surface containing the uPAR (reviewed in Refs. [17,18]).

The present study was prompted by the report of a binding site for uPAR on the α6 integrin in the extracellular β-propeller region [19] and the loss of this region during the α6 to α6p conversion [7]. In addition, the knowledge that both uPA activity and the α6 integrin persist in invasive cancer led us to determine if the α6p conversion via uPA was found in invasive cancer [20–24].

Material and methods

Cells

All human cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Cell lines DU145H and PC3-N were grown in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cell line MCF-10A, was grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F12 (DMEM-F12) (Gibco BRL) plus 5% horse serum, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, and 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone. The MCF-10A (human breast cells) cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). The DU145H cells were isolated by us as previously described [20] and contain only the α6A splice variant [25]. The PC3-N cells are a variant of the PC3 prostate carcinoma cell line [26].

Antibodies and chemicals used in this study

Anti-α6 integrin antibodies include and were obtained as follows: J1B5, rat monoclonal was a generous gift from Dr. Caroline Damsky (University of California, San Francisco, USA) [27]. AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody, which was raised and purified by Bethyl Laboratories Inc. (Montgomery, TX, USA). AA6A is specific for the last 16 amino acids (CIHAQPSDKERLTSDA) of the human α6A sequence [28], as done previously [29]. The urokinase B-chain was recognized by No. 3689 murine IgG1 antibody and the uPAR antibody was No. 399R rabbit polyclonal antibody (American Diagnostica Inc., Greenwich, CT, USA). Rabbit polyclonal-α3 integrin antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) was used and is specific for the carboxy terminal end of the molecule in the cytoplasmic domain. The monoclonal-β4 integrin antibody (3E1) (Chemicon). Urokinase and urokinase recombinant amino-terminal fragment were purchased from Chemicon. Amiloride hydrochloride hydrate, and 4-Aminobenzamidine dihydrochloride, plasmin, and 4-Aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA) were obtained from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 was obtained from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation, La Jolla, CA. YO-2 and YO-4 inhibitors [30] were donated by Dr. Yoshio Okada, Kobe Gakuin University, Japan.

Cell treatments

For inhibitor and blocking antibody experiments, DU145H cells were grown to approximately 40% confluency and the growth media were replaced with fresh media containing different concentrations of the inhibitors or 10 µg/ml antibody or normal IgG of the same subclass. Fresh media with inhibitors/antibodies were replaced every day for a total of 3 days. For uPA and amino-terminal fragment (ATF) treatments, MCF10A and PC3N cells were plated for 3 days and were then treated with different concentrations of uPA and ATF in serum-free or serum-containing media for 90 min. For DU145H conditioned media treatments, serum-containing media from confluent DU145H cells were collected and filtered through 0.2 µm filter and applied to MCF10A cells overnight. In experiments with plasminogen and plasmin-depleted media, medium supplemented with serum was chromatographed on a column of l-lysineagarose that had been washed with 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH7.5, as previously described [31]. The uPA activity was analyzed using the uPA activity assay kit (Chemicon).

Surface Biotinylation of cell lines

Biotinylation was similar to other protocols [32,33]. Briefly, cells were grown to confluency in 100 mm tissue culture dishes and washed three times with HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM CaCl2, pH 7.45). To label the cell surface proteins, the cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with 2 ml of HEPES buffer supplemented with sulfosuccinimidyl hexanoate conjugated biotin (500 µg/ml) (NHS-LC-Biotin, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). They were then washed three times and lysed in cold RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1% (w/v) deoxycholate, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, pH 7.5) plus protease inhibitors (PMSF, 2 mM; leupeptin and aprotinin, 1 µg/ml). The lysate was briefly sonicated on ice before centrifugation at 14,000 RPM for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for immunoprecipitations.

Immunoprecipitations

Cells were grown to confluency and then washed three times with HEPES buffer and lysed in cold RIPA buffer plus protease inhibitors (PMSF, 2 mM; leupeptin and aprotinin, 1 µg/ml). The lysate was briefly sonicated on ice before centrifugation at 14,000 RPM for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for immunoprecipitations. Each reaction contained 200 µg of total protein lysate, 35 µl of protein G sepharose and 5 µg of antibody. The final volume of the lysate was adjusted to 500 µl with RIPA buffer. The mixture was rotated for 18 h at 4°C, and then complexes were washed three times with cold RIPA and pellets were suspended in 2× non-reducing sample buffer. Samples were boiled for 5 min, and after a quick chill on ice, they were loaded onto 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Proteins resolved in the gel were electrotransferred to Millipore Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), incubated with either peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin or Western blotting antibodies plus secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL Western Blotting Detection System, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA).

Cleavage of the α6 integrin in vitro

The α6 integrin was immunoprecipitated from biotinylated cells as described above and after the last wash with the RIPA buffer, the pellets were resuspended in 10 µl of 1× buffer from the uPA activity assay kit (Chemicon) containing 1 µg uPA, or 1 µg uPA and 2.5 mM EDTA, or 0.5 µg/Al APMA, or 0.5 µg/µl APMA and 2.5 mM EDTA, or 4 µg plasmin. The mixtures were incubated overnight on ice and then 10 µl of 2× non-reducing sample buffer were added to each tube. Samples were boiled for 5 min and after a quick chill on ice, they were loaded onto 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Proteins resolved in the gel were electrotransferred to Millipore Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore), incubated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin and visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL Western Blotting Detection System, Amersham).

Zymography

Immunocomplexes were analyzed on gelatin and casein gels, Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Proteolytic activity was analyzed as described by the manufacturer.

Human tissue studies

Snap frozen normal and cancerous tissues from human prostates were obtained, and approximately 125 mm3 of tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer by the use of a polytron homogenizer. The samples were then centrifuged at approximately 14000 RPM at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatants were collected, sonicated, and immunoprecipitated using the J1B5 antibody and Western blotted using the AA6A antibody as described above.

Protein band quantification

Protein bands were quantitated using Scion Image Analysis software as previously described [34] and the data were graphed using Sigma Plot software.

Results

Significant abundance of α6p on the cell surface of DU145H cells

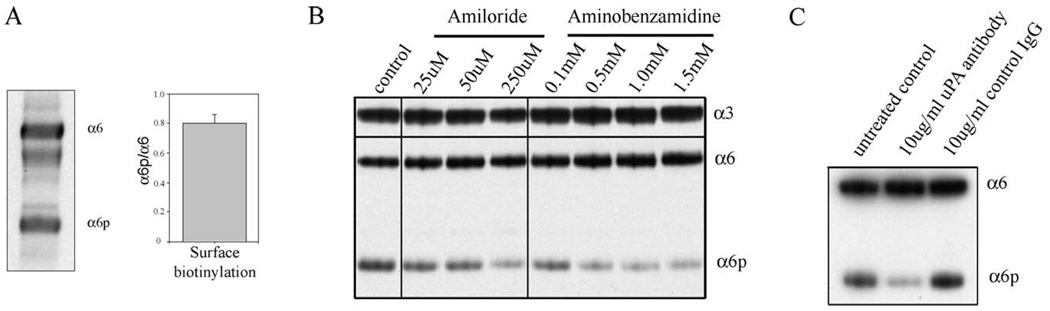

To investigate the levels of α6p on the cell surface, we compared the levels of α6 and α6p integrin on the surface of DU145H cells. The cells were surface-biotinylated and α6 and α6p were isolated by immunoprecipitations. The resulting data (Fig. 1A) showed that the ratio of α6p to α6 was 0.8, indicating significant abundance of α6p on the cell surface.

Fig. 1.

Inhibitors and a blocking antibody of uPA reduce α6p levels in DU145H cells (A) DU145H cells were surface biotinylated and α6 and α6p were immunoprecipitated using the AA6A antibody. The samples were analyzed using streptavidin-HRP and the bands were quantified using the Scion Image software and the graph was plotted using Sigma Plot. (B) DU145H cells were treated with different concentrations of Amiloride or aminobenzamidine. The samples were analyzed for α6 and α6p integrin levels using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody and α3 integrin using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). (C) DU145H cells were treated with a uPA blocking antibody or control IgG for 3 days. The samples were analyzed for α6 and α6p integrin levels using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Modulation of uPA alters the production of α6p integrin

In our studies to identify the protease involved in the cleavage of the α6 integrin, we used different inhibitors including MMP inhibitors, general serine protease inhibitors, and others (data not shown). We have used four different conditions to inhibit uPA and three different conditions to stimulate uPA to investigate the involvement of uPA in the production of α6p. Amiloride is a uPA inhibitor [35], and aminobenzamidine is broad-spectrum serine proteinase inhibitor [36]. The amiloride treatments of 25, 50, and 250 µM and the aminobenzamidine treatments of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mM (Fig. 1B) reduced the levels of α6p relative to the untreated DU145H cells. The uPA-blocking antibody (Fig. 1C) reduced the levels of α6p relative to the untreated control and the 10 µg/ml unrelated IgG of the same subclass. In addition, we have used different concentrations of PAI-1. PAI-1 completely abolished the levels of α6p in DU145H cells (Fig. 2C). Even at the lower concentration of 2.15 µg/ml, PAI-1 completely abolished α6p levels (data not shown). Taken together these data indicate that the inhibition of uPA activity inhibits α6p production.

Fig. 2.

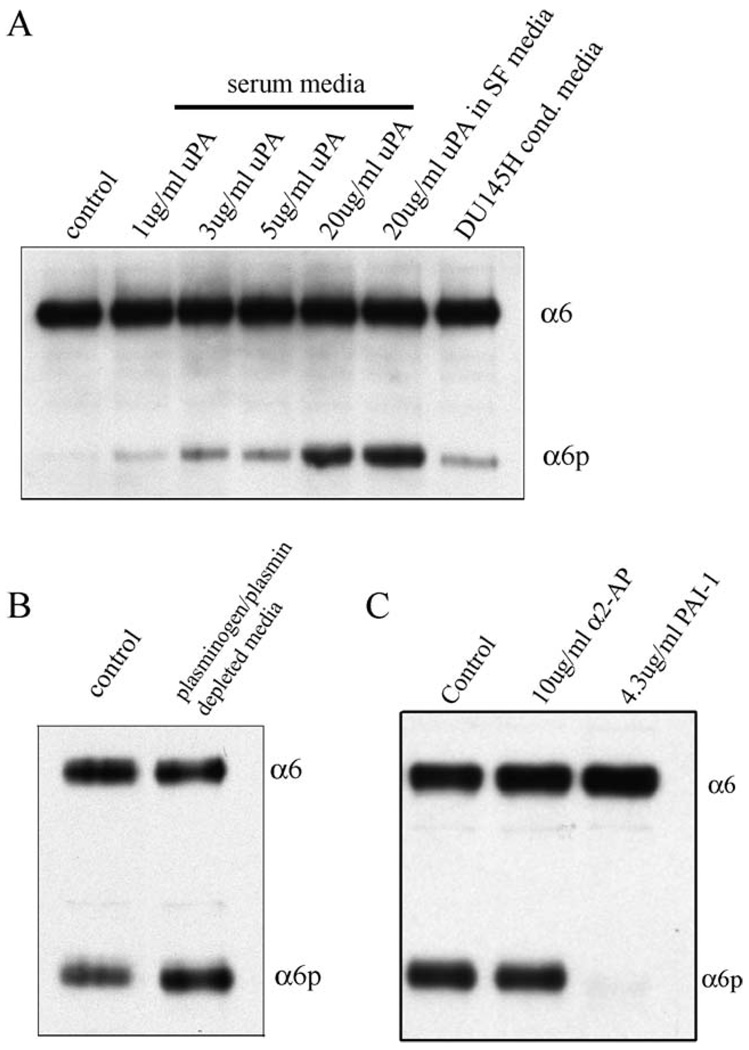

The production of α6p by addition of uPA in MCF10A cells is plasmin independent (A) MCF10A cells were cultured for 3 days and then treated for 90 min with different concentrations of purified uPA or DU145H conditioned media overnight. The samples were analyzed for α6 and α6p integrin levels using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody. (B) DU145H cells were either untreated or treated with plasmin depleted media for 3 days. The samples were analyzed for α6 and α6p integrin levels using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody. (C) DU145H cells were treated with α2-antiplasmin or PAI-1 for 3 days. The samples were analyzed for α6 and α6p integrin levels using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody.

To further investigate the involvement of uPA in α6p production, exogenous uPA was added to a cell line (MCF10A) that does not have α6p, to determine if production of α6p was stimulated. The cells were treated with 1, 3, 5, and 20 µg uPA for 90 min in serum containing media (Fig. 2A, lanes 2–5). The addition of uPA to the cells induced a dose-dependent production of α6p.

Previous reports showed that DU145 cells contain high levels of uPA relative to normal cells [37], and in addition, these cells have no plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1 or PAI-2) proteins present [38]. Therefore, we replaced the media from MCF10A cells with DU145H-conditioned media and incubated them overnight and observed production of α6p in MCF10A cells (Fig. 2A, lane 7) indicating that uPA secreted by DU145H cells could cleave the α6 integrin in MCF10A cells.

Production of α6p by uPA is plasmin-independent

Many of the effects of uPA are mediated by plasmin. For example, uPA-mediated plasminogen activation resulted in the proteolytic processing of the globular region of laminin 5 in oral keratinocytes [39]. We therefore investigated whether the uPA-induced cleavage of the α6 integrin is plasmin mediated. First, we incubated DU145H cells with different concentrations of α2-antiplasmin (data not shown). Even at the highest dose which was not toxic to the cells (10 µg/ml), α6p levels were not affected. Higher concentrations of α2-antiplasmin (20 µg/ml) were toxic to the cells.

Then, we incubated MCF10A cells with purified uPA in the presence of serum-free (SF) media and observed that α6p was produced (Fig. 2A, lane 6). Then DU145H cells were grown in plasminogen and plasmin-depleted media, and there was no reduction in the level of α6p relative to the untreated control (Fig. 2B). In addition, we treated DU145H cells with α2-antiplasmin or PAI-1 for 3 days and only PAI-1 abolished α6p levels. Finally, we used chemical agents, YO-2 and YO-4, to determine if plasmin is involved in the α6 integrin processing. The YO-2 agent inhibits plasmin and uPA, whereas YO-4 inhibits plasmin alone and not uPA [30]. Only YO-2 reduced α6p production (not shown), indicating that plasmin was not involved. Collectively, these data suggest that plasmin is not involved in the production of α6p.

Signaling through uPA receptor was not sufficient for α6p production

Our next experiments investigated whether uPAR signaling was involved in α6p production. There are several reports indicating that uPAR not only targets the uPA enzyme activity but that the uPA binding to uPAR also can initiate activation of signaling cascades [40–47]. Receptor-bound uPA does not become internalized and degraded rapidly unless associated with plasminogen activator inhibitor [48–51].

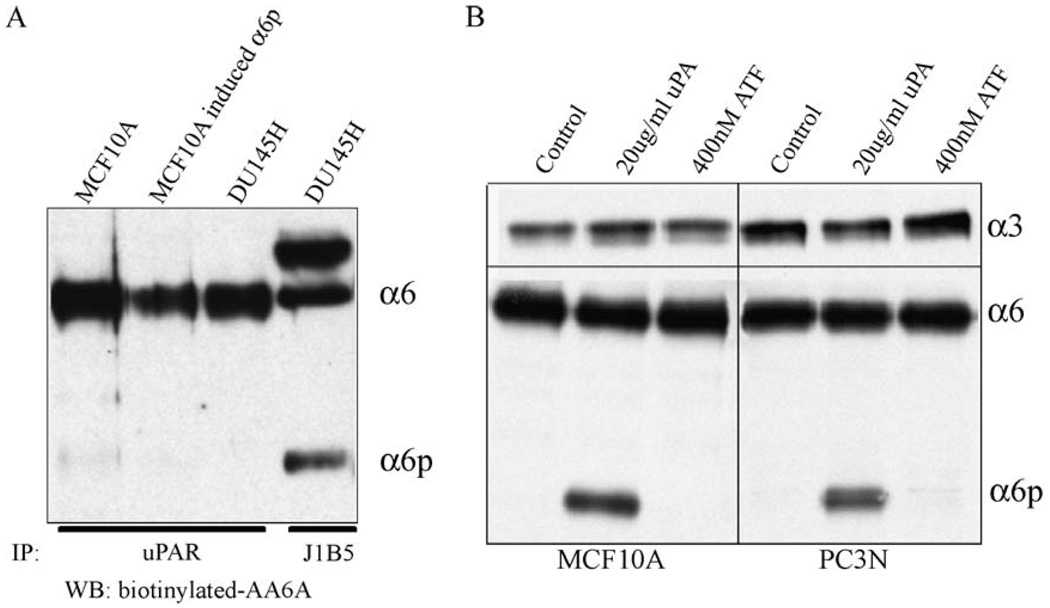

We first determined if uPAR associates with α6 or α6p integrin since the amino acid sequences in the β-propeller domain involved in the α6 integrin-uPAR interaction have been identified [19]. Lysates from MCF10A and DU145H cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-uPAR, and the presence of α6 or α6p was detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). As expected, retrieval of uPAR retrieved the α6 integrin. The α6p was not associated with uPAR from either cells induced to express α6p or in cells containing constitutive expression of α6p (Fig. 3A). This is in agreement with previous published results, which show that the uPAR-integrin α subunit interaction is mediated through the β-propeller region of the integrin α subunit (amino acid position 264–289) [19], and this region has been shown to be missing from α6p [7].

Fig. 3.

uPAR associates with the α6 integrin but not α6p, and uPAR signaling is not sufficient to produce α6p (A) DU145H and MCF10A cells were cultured for 3 days and immunoprecipitated with anti-uPAR antibody or with anti-α6 antibody J1B5. Samples were blotted for the α6 integrin using the AA6A-biotinylated antibody. (B) MCF10A and PC3N cells were cultured for 3 days and were then treated with 20 µg/ml uPA or 400 nM ATF for 1.5 h. The samples were analyzed for α6 and α6p integrin levels using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Next, we used the amino-terminal fragment (ATF) of uPA, which has been shown to induce signaling through uPAR, to determine if the fragment alone was sufficient to induce α6p production. We used different concentrations of ATF ranging from 10 to 400 nM and did not observe α6p production (not shown). The highest dose (400 nM) of ATF did not produce α6p in MCF10 A or PC3N cells, whereas purified uPA produced α6p both in MCF10A and PC3N cells (Fig. 3B). Also, addition of uPA to MCF10A and PC3N cells did not induce a smaller variant of the α3 integrin, indicating that the α6 integrin cleavage by uPA is specific for α6 integrin (Fig. 3B). Moreover, addition of uPA did not result in cleavage of other integrins including α2, α5, and αV (data not shown).

Finally, we wanted to investigate the involvement of uPAR in α6p production. We treated DU145H cells, twice daily, with ATF for 3 days to compete with uPA for binding to the receptor. We did not observe any effect on α6p levels (data not shown). We also treated DU145H cells with N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, which was shown to inhibit the interaction of integrins with uPAR [52] and saw no effect on α6p levels (data not shown). These results suggested that the α6 integrin-uPAR interaction was not important in the production of α6p.

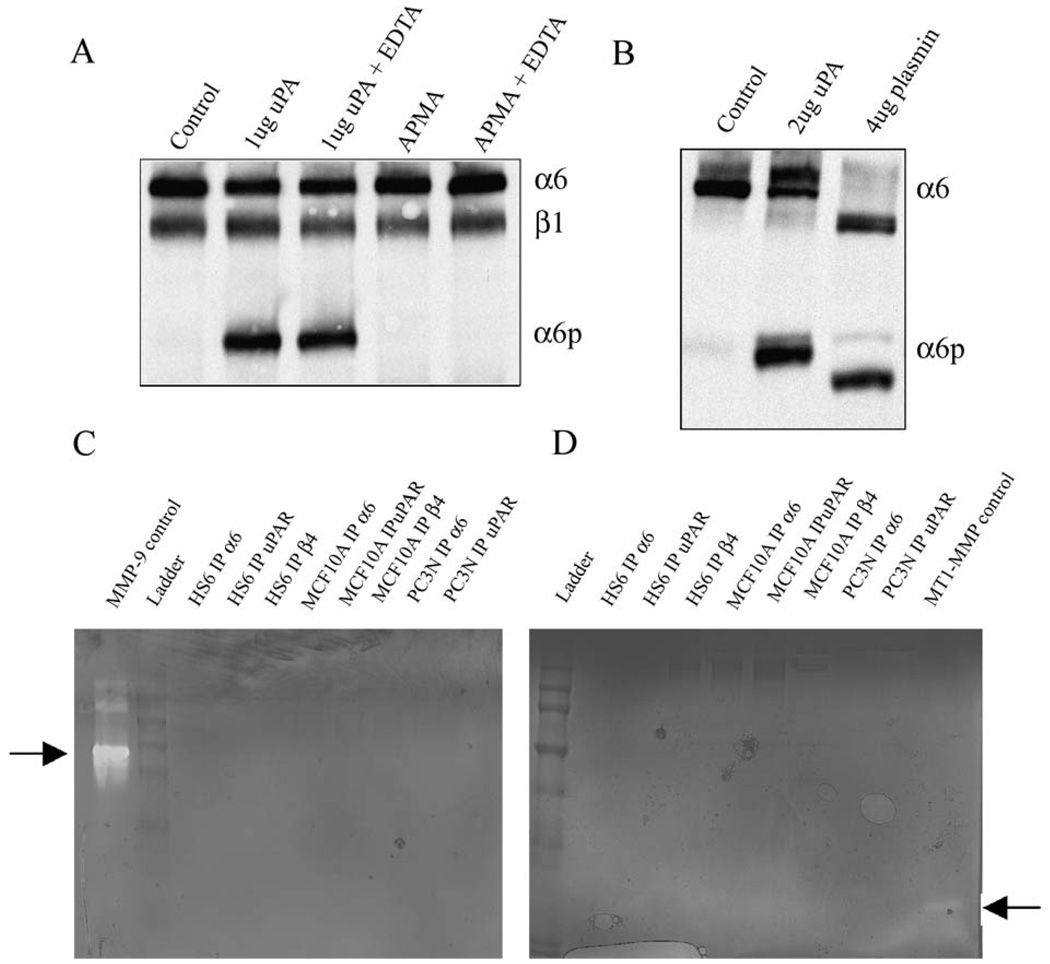

uPA cleaves the α6 integrin in vitro

We next determined whether uPA is able to cleave the α6 integrin directly in vitro or whether the cleavage of α6 integrin could be mediated by a contaminating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP). To distinguish between these possibilities, the MCF10A cell surface integrin was labeled by biotinylation, and resulting biotinylated α6 integrin retrieved by immunoprecipitation. The immunoprecipitated material was incubated with uPA, or other compounds for 1 h, and the resulting products analyzed by SDS-PAGE and detected via streptavidin-HRP (Fig. 4A). The addition of uPA to the immunocomplexes produced α6p integrin in vitro. The presence of EDTA did not interfere with the cleavage of the α6 integrin by uPA suggesting that uPA does not activate a contaminating MMP in the immunocomplex. Addition of APMA, an MMP activator, to the immunoprecipitates did not result in production of α6p indicating that MMPs are not involved in α6p production. The addition of EDTA, as divalent cation chelator, is also known to reversibly dissociate the heterodimer into its individual subunits; this treatment was shown to not produce α6p (not shown). It is interesting that plasmin, while capable of cleaving α6 in vitro, produced cleavage products that are different from those generated by uPA (Fig. 4B). These data show that while both uPA and plasmin can cleave α6 integrin in vitro, the products are distinct. The in vitro pattern of α6 integrin cleavage by uPA rather than plasmin matches the in vivo cleavage pattern of α6. Finally, to investigate if any other proteases were present in the immunocomplexes, we performed casein and gelatin zymography. Immunocomplexes containing α6 integrin, α6β4 integrin or uPAR from different cell lines were analyzed. Co-precipitating protease activity was not detected in any sample (Figs. 4 C, D).

Fig. 4.

uPA can cleave the α6 integrin directly in vitro (A and B) Surface biotinylated proteins from MCF10A cells were retrieved by immunoprecipitation using the AA6A antibody and the washed immunoprecipitates were either untreated or treated with the different compounds indicated. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and blotted for HRP-streptavidin. (C and D) Whole cell lysates from different cell lines were immunoprecipitated with different antibodies and the immunocomplexes were run on gelatin gels (C) or casein gels (D) to detect proteolytic activity. The proteolytic activity of the controls is indicated by arrows.

Phorbol ester induction of α6p

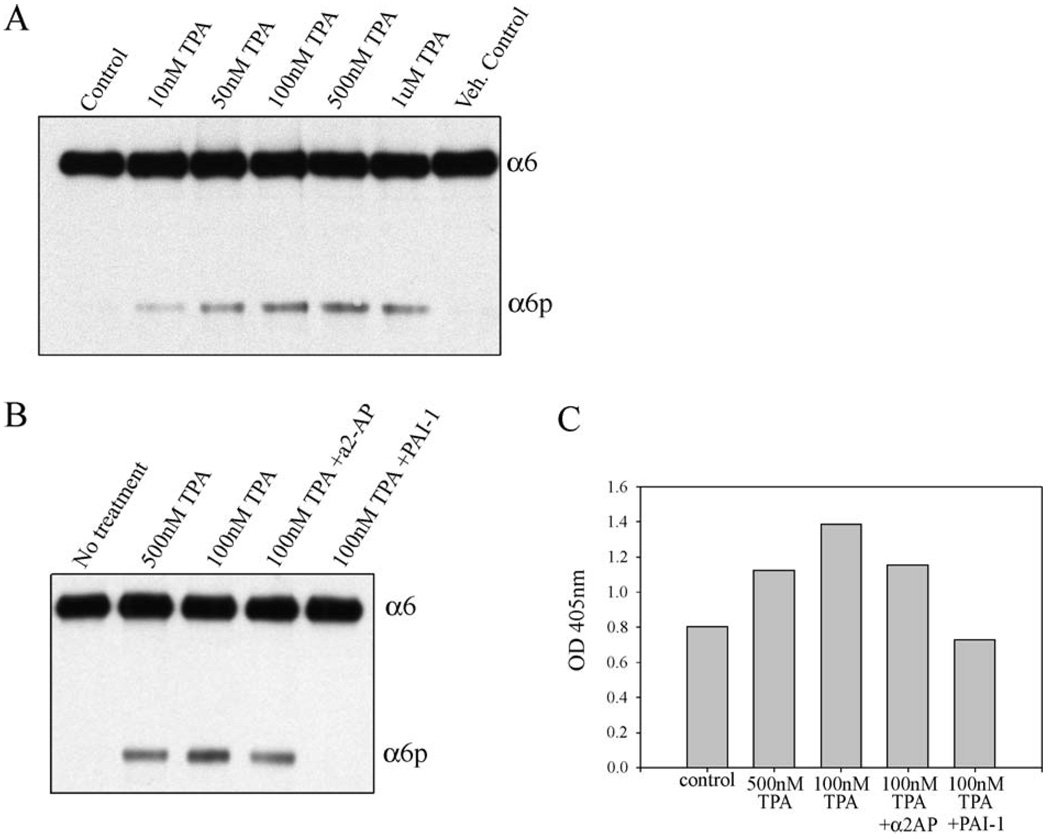

It has been previously reported that 12-o-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) induces uPA activity in MCF10A cells [31]. We investigated whether TPA could induce α6p production. An induction of α6p relative to the vehicle controls was observed dependent upon different concentrations of TPA (Fig. 5A). No α6p was detected in the untreated cells. In addition, to confirm that the production of α6p was induced by uPA we used PAI-1 inhibitor and showed that uPA was involved (Fig. 5B). We also used the plasmin inhibitor α2-antiplasmin and found that the cleavage of the α6 integrin was plasmin independent (Fig. 5B). Finally, we analyzed the media from the cell treatments (described in Fig. 5B) for uPA activity (Fig. 5C). The levels of α6p from Fig. 5B correspond to the uPA activity in Fig. 5C.

Fig. 5.

TPA induces α6p in MCF10A cells (A) MCF10A cells were cultured for four days and were then treated with different concentrations of TPA for 18 h. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and a Western blot was performed for the α6 integrin using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody. (B) MCF10A cells were cultured for four days and were then treated with different concentrations of TPA or with TPA and different inhibitors for 18 h. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and a Western blot was performed for the α6 integrin using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody. (C) Media from the samples from panel B was analyzed for uPA activity using the uPA activity assay kit (Chemicon International).

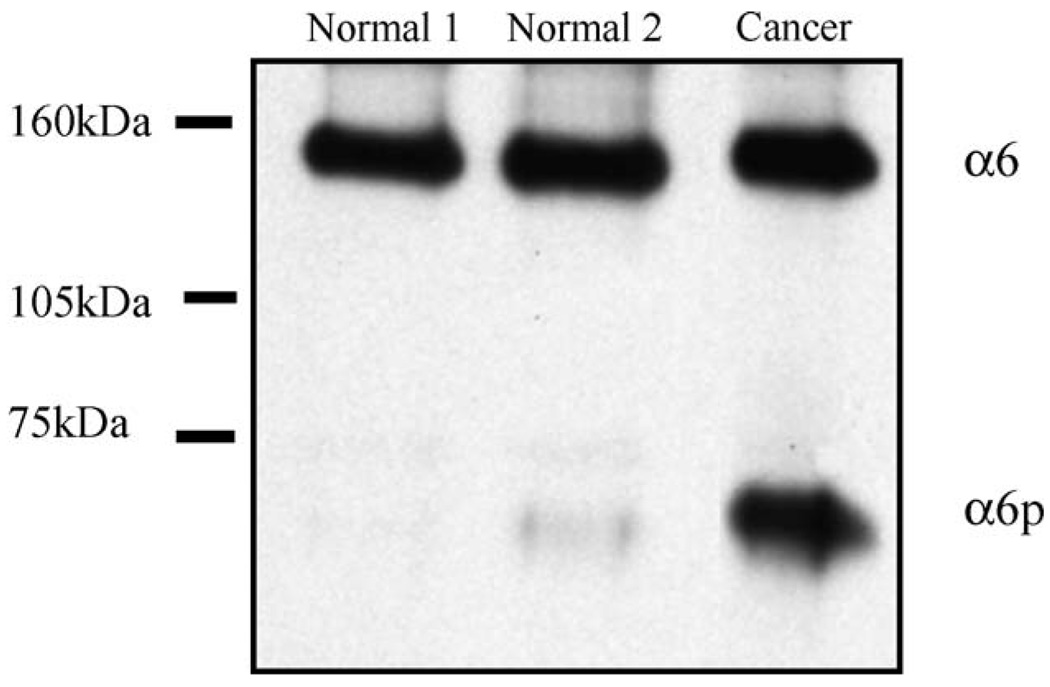

α6p is present in prostate cancer tissue

Our results so far suggested that α6p was produced via uPA in tissue culture cell lines and that TPA could induce α6p production. Our next step was to determine whether α6p was present in human tissue. Since α6p was first identified in a prostate cancer cell line (DU145H), we obtained human normal and prostate cancer tissue specimens. The tissue was obtained from frozen tissue blocks, and the resulting lysates were immunoprecipitated with the α6 antibody (J1B5); and then a Western blot was performed using an anti-α6 antibody (AA6A) specific for the cytoplasmic domain. The full-length α6 integrin was detected in both the normal and the cancer tissue, while the α6p form was present predominantly in the prostate cancer specimen (Fig. 6). These data suggest that α6p can be found in human prostate cancer tissue specimens as well as in prostate cancer tissue culture cell lines.

Fig. 6.

α6p is present in human prostate tissues. Normal and cancer human prostate tissues were analyzed for α6 and α6p levels by immunoprecipitation with the J1B5 rat monoclonal antibody and Western blotting using the AA6A rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Discussion

Our previous work has shown that the α6 integrin is associated with an increased invasive potential of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and the progression of human prostate carcinoma in human tissue biopsy material [20,21]. In addition, we have shown that during prostate cancer progression, many integrin receptors, with the exception of α3 and α6, are not expressed [25]. Finally, we have shown that the α6 integrin exists in the classical form (140 kDa, non-reduced) and in a novel smaller form (70 kDa) called α6p [7]. Our previous studies in DU145H cells suggested that the production of the α6p variant involves a post-translational processing event at the cell surface [8].

Previous reports showed that DU145 cells contained five times the level of uPA compared to normal cells [37], and in addition, these cells had no PAI-1 or PAI-2 proteins present [38]. In addition, it has been shown that the α6 integrin interacts with the uPA receptor [52,53]. Combined, these observations led us to investigate the possible involvement of uPA in the production of the α6p integrin variant.

We now have evidence indicating that the α6p integrin variant is produced by direct cleavage by uPA. Inhibitors of uPA and a uPA-blocking function antibody reduced the levels of α6p in DU145H cells suggesting that uPA is involved in the proteolytic cleavage of the α6 integrin. The addition of uPA to cell lines lacking α6p induced α6p production in a manner that was dose-dependent on uPA. This unique action of uPA is not dependent upon plasmin. While plasmin is capable of cleaving the α6 integrin in vitro, the cleavage products do not correspond to those generated by uPA in vitro or in vivo. In addition, the cleavage of the α6 integrin occurs independently of the signaling functions of uPAR or integrin uPAR interaction as indicated by the uPA amino-terminal-fragment (ATF) studies and the N-acetyl-d-glucosamine studies, respectively. Furthermore, while both the α6 and α3 integrin have amino acid binding sites for uPAR, only the α6 integrin is cleaved. This implies that some additional factor(s) independent of uPAR regulates the cleavage. Our experiments indicate that the production of α6p is an inducible event dependent on uPA activity. Human breast epithelial cells (MCF10A) produce uPA after phorbol ester (TPA) stimulation [31], and our work indicates that TPA induces α6p production in a uPA dependent manner. Of particular interest is that the event appears highly regulated since only a portion of the α6 integrin on the cell surface is cleaved. In addition, the inhibition of α6p production does not increase the level of the α6 integrin. Current studies are to determine the regulatory features of the α6p production.

Studies indicated that α6p was present in human tissue and that it is not a tissue culture phenomenon. Since the α6p form of the integrin is missing the β-propeller domain while maintaining the heterodimer on the surface, it would be of interest to localize the expression of α6p on the cell surface in remodeling epithelial tissues. Our working hypothesis is that the α6p form of the integrin would allow disattachment of the cell from the extracellular matrix while preserving the connections of the beta subunit to the cytoskeleton within the cell. Current work is underway to develop reagents that are specific for the α6p form in tissue.

The exact site where uPA cleaves the α6 integrin resulting in the loss of the β-propeller domain is unknown. However, mass spectrometry analysis of the α6p form [7] indicates that the NH2 terminal end of the molecule contains at least the ‘genu’ region and a portion of an exposed loop in the thigh domain of the molecule while amino acid residues corresponding to the β-propeller and most of the “thigh” region are not detectable. We are currently investigating the interesting possibility that α6 integrin is cleaved within the exposed loop in the thigh region.

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator has been shown to cleave a variety of extracellular molecules either through plasminogen activation or directly. For example, it has been shown that uPA cleaves laminin 5 through plasminogen activation [39], and that it cleaves hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) [11], macrophage-stimulating protein (MSP) [12], and fibronectin [10] directly. To our knowledge, this is the first report that uPA is involved in the cleavage of an integrin. The production of α6p may be a crucial step during tissue remodeling or toward uPA-induced migration and invasion in cancer progression.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Michael B. Berman, University of Arizona, USA, for conceptual contributions, and Dr. Yoshio Okada, Kobe Gakuin University, Japan, for providing us the YO-2 and YO-4 inhibitors.

This work was supported by Grants CA56666, CA75152 and CA23074 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranti CK, Brugge JS. Sensing the environment: a historical perspective on integrin signal transduction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:E83–E90. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green LJ, Mould AP, Humphries MJ. The integrin beta subunit. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998;30:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Frech M, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3 in complex with an Arg –Gly –Asp ligand. Science. 2002;296:151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnaout MA, Goodman SL, Xiong JP. Coming to grips with integrin binding to ligands. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:641–651. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis TL, Rabinovitz I, Futscher BW, Schnolzer M, Burger F, Liu Y, Kulesz-Martin M, Cress AE. Identification of a novel structural variant of the alpha 6 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:26099–26106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102811200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis TL, Buerger F, Cress AE. Differential regulation of a novel variant of the alpha(6) integrin, alpha(6p) Cell Growth Diff. 2002;13:107–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rickli EE. The activation mechanism of human plasminogen. Thromb. Diath. Haemorrh. 1975;34:386–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold LI, Schwimmer R, Quigley JP. Human plasma fibronectin as a substrate for human urokinase. Biochem. J. 1989;262:529–534. doi: 10.1042/bj2620529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naldini L, Tamagnone L, Vigna E, Sachs M, Hartmann G, Birchmeier W, Daikuhara Y, Tsubouchi H, Blasi F, Comoglio PM. Extracellular proteolytic cleavage by urokinase is required for activation of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. EMBO J. 1992;11:4825–4833. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazawa K, Wang Y, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Kitamura N. Structural organization and chromosomal localization of the human hepatocyte growth factor activator gene– phylogenetic and functional relationship with blood coagulation factor XII, urokinase, and tissue-type plasminogen activator. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;258:355–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stepanova VV, Tkachuk VA. Urokinase as a multidomain protein and polyfunctional cell regulator. Biochemistry (Russia) 2002;67:109–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1013912500373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rijken DC. Plasminogen activators and plasminogen activator inhibitors: biochemical aspects. Bailliere’s Clin. Haematol. 1995;8:291–312. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(05)80269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robison AK, Collen D. Activation of the fibrinolytic system. Cardiol. Clin. 1987;5:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurewich V. Fibrinolysis: an unfinished agenda. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 2000;11:401–408. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mignatti P, Rifkin DB. Biology and biochemistry of proteinases in tumor invasion. Physiol. Rev. 1993;73:161–195. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dano K, Andreasen PA, Grondahl-Hansen J, Kristensen P, Nielsen LS, Skriver L. Plasminogen activators, tissue degradation, and cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 1985;44:139–266. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei Y, Eble JA, Wang Z, Kreidberg JA, Chapman HA. Urokinase receptors promote beta1 integrin function through interactions with integrin alpha3beta1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2975–2986. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabinovitz I, Nagle RB, Cress AE. Integrin alpha 6 expression in human prostate carcinoma cells is associated with a migratory and invasive phenotype in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1995;13:481–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00118187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmelz M, Cress AE, Scott KM, Burger F, Cui H, Sallam K, McDaniel KM, Dalkin BL, Nagle RB. Different phenotypes in human prostate cancer: alpha6 or alpha3 integrin in cell-extracellular adhesion sites. Neoplasia (New York) 2002;4:243–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheng S. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator system in prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20:287–296. doi: 10.1023/a:1015539612576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohta S, Fuse H, Fujiuchi Y, Nagakawa O, Furuya Y. Clinical significance of expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator in patients with prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2945–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt M, Janicke F, Moniwa N, Chucholowski N, Pache L, Graeff H. Tumor-associated urokinase-type plasminogen activator: biological and clinical significance. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler. 1992;373:611–622. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1992.373.2.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cress AE, Rabinovitz I, Zhu W, Nagle RB. The alpha 6 beta 1 and alpha 6 beta 4 integrins in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1995;14:219–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00690293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran NL, Nagle RB, Cress AE, Heimark RL. N-cadherin expression in human prostate carcinoma cell lines. An epithelial-mesenchymal transformation mediating adhesion with stromal cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;155:787–798. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damsky CH, Librach C, Lim KH, Fitzgerald ML, McMaster MT, Janatpour M, Zhou Y, Logan SK, Fisher SJ. Integrin switching regulates normal trophoblast invasion. Dev. Suppl. 1994;120:3657–3666. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura RN, Rozzo C, Starr L, Chambers J, Reichardt LF, Cooper HM, Quaranta V. Epithelial integrin alpha 6 beta 4: complete primary structure of alpha 6 and variant forms of beta 4. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:1593–1604. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper HM, Tamura RN, Quaranta V. The major laminin receptor of mouse embryonic stem cells is a novel isoform of the alpha 6 beta 1 integrin. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115:843–850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada Y, Tsuda Y, Tada M, Wanaka K, Okamoto U, Hijikata-Okunomiya A, Okamoto S. Development of potent and selective plasmin and plasma kallikrein inhibitors and studies on the structure-activity relationship. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000;48:1964–1972. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo M, Mathieu PA, Linebaugh B, Sloane BF, Reiners JJ., Jr Phorbol ester activation of a proteolytic cascade capable of activating latent transforming growth factor-betaL a process initiated by the exocytosis of cathepsin B. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14829–14837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Einheber S, Milner TA, Giancotti F, Salzer JL. Axonal regulation of Schwann cell integrin expression suggests a role for alpha 6 beta 4 in myelination. J. Cell Biol. 1993;123:1223–1236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isberg RR, Leong JM. Multiple beta 1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell. 1990;60:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cress AE. Quantitation of phosphotyrosine signals in human prostate cell adhesion sites. Biotechniques. 2000;29:776. doi: 10.2144/00294st03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vassalli JD, Belin D. Amiloride selectively inhibits the urokinase-type plasminogen activator. FEBS Lett. 1987;214:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geratz JD, Cheng MC. The inhibition of urokinase by aromatic diamidines. Thromb. Diath. Haemorrh. 1975;33:230–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waghray A, Webber MM. Retinoic acid modulates extracellular urokinase-type plasminogen activator activity in DU-145 human prostatic carcinoma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 1995;1:747–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyon PB, See WA, Xu Y, Cohen MB. Diversity and modulation of plasminogen activator activity in human prostate carcinoma cell lines. Prostate. 1995;27:179–186. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990270402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghosh S, Brown R, Jones JC, Ellerbroek SM, Stack MS. Urinary-type plasminogen activator (uPA) expression and uPA receptor localization are regulated by alpha 3beta 1 integrin in oral keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23869–23876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumler I, Weis A, Mayboroda OA, Maasch C, Jerke U, Haller H, Gulba DC. The Jak/Stat pathway and urokinase receptor signaling in human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:315–321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshelnick Y, Ehart M, Hufnagl P, Heinrich PC, Binder BR. Urokinase receptor is associated with the components of the JAK1/STAT1 signaling pathway and leads to activation of this pathway upon receptor clustering in the human kidney epithelial tumor cell line TCL-598. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28563–28567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen DH, Catling AD, Webb DJ, Sankovic M, Walker LA, Somlyo AV, Weber MJ, Gonias SL. Myosin light chain kinase functions downstream of Ras/ERK to promote migration of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-stimulated cells in an integrin-selective manner. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:149–164. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen DH, Hussaini IM, Gonias SL. Binding of urokinase-type plasminogen activator to its receptor in MCF-7 cells activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 which is required for increased cellular motility. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:8502–8507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohuslav J, Horejsi V, Hansmann C, Stockl J, Weidle UH, Majdic O, Bartke I, Knapp W, Stockinger H. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, beta 2-integrins, and Src-kinases within a single receptor complex of human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1381–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang H, Kerins DM, Hao Q, Inagami T, Vaughan DE. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor mediates tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cultured endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18268–18272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sitrin RG, Pan PM, Harper HA, Todd RF, III, Harsh DM, Blackwood RA. Clustering of urokinase receptors (uPAR; CD87) induces proinflammatory signaling in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2000;165:3341–3349. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu D, Ghiso JA, Estrada Y, Ossowski L. EGFR is a transducer of the urokinase receptor initiated signal that is required for in vivo growth of a human carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00072-7. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neilsen L, Hansen J, Skriver L, Wilson E, Kaltoft K, Zenthen J, Dano K. Purification of zymogen to plasminogen activator from human glioblastoma cells by affinity chromatography with monoclonal antibody. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6410–6415. doi: 10.1021/bi00268a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vassali J, Baccino D, Belin D. A cellular binding site for the Mr 55,000 form of the human plasminogen activator, urokinase. J. Cell Biol. 1985;100:86–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoppelli MP, Corti A, Soffientini A, Cassani G, Blasi F, Assoian RK. Differentiation-enhanced binding of the amino-terminal fragment of human urokinase plasminogen activator to a specific receptor on U937 monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985;82:4939–4943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cubellis MV, Wun TC, Blasi F. Receptor-mediated internalization and degradation of urokinase is caused by its specific inhibitor PAI-1. EMBO J. 1990;9:1079–1085. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xue W, Mizukami I, Todd RF, III, Petty HR. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptors associate with beta1 and beta3 integrins of fibrosarcoma cells: dependence on extracellular matrix components. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1682–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tarui T, Mazar AP, Cines DB, Takada Y. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (CD87) is a ligand for integrins and mediates cell– cell interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3983–3990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]