Abstract

Chromium (Cr) is a cytotoxic metal that can be associated with a variety of types of DNA damage, including Cr-DNA adducts and strand breaks. Prior studies with purified human cytochrome b5 and NADPH :P450 reductase in reconstituted proteoliposomes (PLs) demonstrated rapid reduction of CrVI (hexavalent chromium, as ), and the generation of CrV, superoxide , and hydroxyl radical (HO˙). Studies reported here examined the potential for the species produced by this system to interact with DNA. Strand breaks of purified plasmid DNA increased over time aerobically, but were not observed in the absence of O2. CrV is formed under both conditions, so the breaks are not mediated directly by CrV. The aerobic strand breaks were significantly prevented by catalase and EtOH, but not by the metal chelator diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), suggesting that they are largely due to HO˙ from Cr-mediated redox cycling. EPR was used to assess the formation of Cr-DNA complexes. Following a 10-min incubation of PLs, , and plasmid DNA, intense EPR signals at g = 5.7and g = 5.0 were observed. These signals are attributed to specific CrIII complexes with large zero field splitting (ZFS). Without DNA, the signals in the g = 5 region were weak. The large ZFS signals were not seen, when CrIIICl3 was incubated with DNA, suggesting that the CrIII–DNA interactions are different when generated by the PLs. After 24 h, a broad signal at g = 2 is attributed to CrIII complexes with a small ZFS. This g = 2 signal was observed without DNA, but it was different from that seen with plasmid. It is concluded that EPR can detect specific CrIII complexes that depend on the presence of plasmid DNA and the manner in which the CrIII is formed.

Introduction

While small amounts of chromium (Cr) are naturally present in many environments, the major human exposures are from industrial uses and release. Greater than 105 tons of Cr are released annually into the environment, and Cr is a significant contaminant at hundreds of sites (Superfund and other) across the USA [1– 3].

CrVI and CrIII are the predominant stable oxidation states. CrIII Species are generally insoluble and do not easily cross cell membranes [4]. Several CrVI compounds, e.g., chromates , are soluble and, given their similarity to sulfate, can be rapidly transported into cells via an anion carrier [5]. While some industrially used chromates are water-insoluble, they are still implicated in toxicity. CrVI Exposure is often considered a predisposing factor to Cr-induced toxicity [6– 10].

Once internalized, cells rapidly reduce CrVI by a variety of possible reductants including ascorbate, cysteine, glutathione, glutathione reductase, microsomal enzymes, and others [11 – 18]. These reductants mediate either one- or two-electron transfers in biological systems, so the reduction of CrVI to CrIII results in the generation of the intermediates CrV and/or CrIV. These intermediates have high reactivity and likely contribute to toxicity resulting from CrVI exposure [9] [19 – 23]. Different intracellular CrVI reductants could result in the generation of distinct types of reactive species. In human systems, NADPH-dependent lung and liver microsomal enzymes generate CrV, CrIV, and CrIII from [24]. In particular, human cytochrome b5 plus P450 reductase have prominent CrVI-reducing activity [18] [25]. The nature of the resulting CrV and CrIII species are not known with certainty, but various Cr-carbohydrate, Cr-NAD(P)H, and other species might result from ligand exchange reactions [26].

In vitro, the reduction of CrVI by at least some reductants can lead to various types of DNA damage including DNA strand breaks [27– 29]. Similarly, exposure of animal and human cells to CrVI results in DNA strand breaks [30 – 33]. While CrVI does not significantly react with or bind DNA [34], both CrV and CrIII have known effects on DNA. For example, a CrV complex can directly mediate strand breaks [35].

The reduction of CrVI by ascorbate yields CrIII-DNA adducts, a portion of which can cause polymerase arrest [36]. CrIII can also bind DNA [34], and at least a subset of the resulting CrIII-DNA adducts can interfere with DNA replication [37] [38].

Furthermore, CrV, CrIV, and CrIII are all capable of reacting with H2O2 to generate HO˙ via Cr-mediated Fenton-like reactions. Of these, CrIII is the slowest, whereas CrV and CrIV are highly active [14] [39– 43]. In accord, oxidation of CrIII picolinate by H2O2 can result in the regeneration of higher oxidation states such as CrVI [44]. In the presence of low micromolar concentrations of CrVI, the human microsomal enzymes cytochrome b5 plus P450 reductase generate superoxide (O2˙−) and a stoichiometric excess of HO˙ via the redox cycling of CrV [18]. This system generates its own H2O2 to support this process. These microsomal enzymes are located in the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear membrane so the resulting reactive oxygen species could damage the nuclear membrane and potentially even the DNA.

The goal of these studies was to better understand some of the consequences of CrVI reduction by the human microsomal enzymes cytochrome b5 plus P450 reductase. One goal was to determine if this reduction was capable of causing DNA strand breaks in vitro, and if these strand breaks were due to CrV or to reactive oxygen species. Another goal was to determine if specific CrV and/or CrIII EPR signals could be detected that would be indicative of Cr–DNA interactions or complexes.

Results and Discussion

DNA Strand Breaks

Various chemical reductants of CrVI can generate species that result in DNA damage including strand breaks. These strand breaks could be caused by the reactive Cr intermediates CrV and/or CrIV, or by HO˙ if H2O2 is included [28] [35] [43] [45] [46].

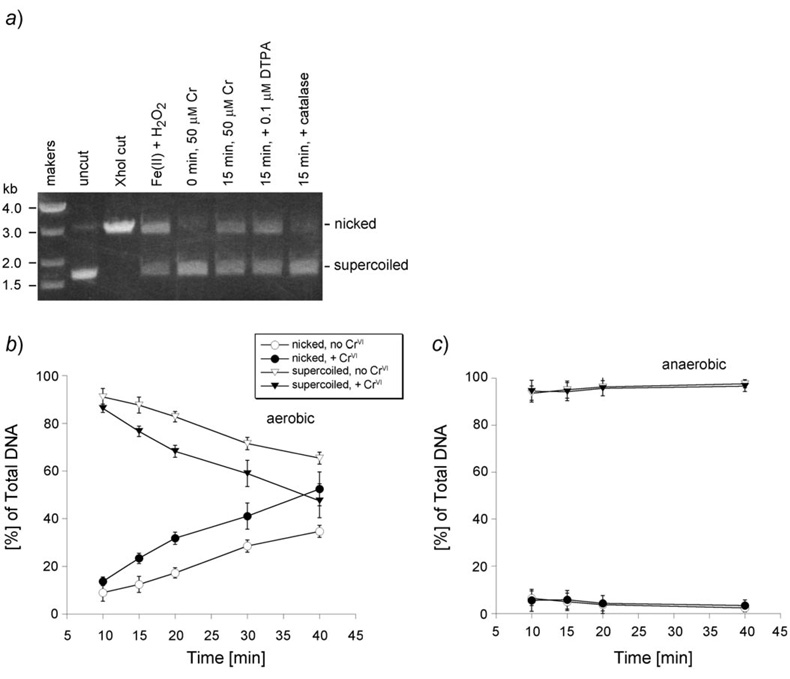

Previous studies with proteoliposomes (PLs) demonstrated that they reduce in an NADPH-dependent manner, generating the reactive intermediate CrV, and HO˙ under aerobic conditions via the redox cycling of Cr [18]. Since both have the potential to damage DNA, the generation of DNA breaks as a consequence of CrVI reduction by this system was examined using a plasmid nicking assay. Plasmid DNA represents natural double-stranded DNA with sequence variety. Its circular nature facilitates the assay. The majority of isolated plasmid is supercoiled (SC), which migrates faster than plasmid with DNA strand breaks, which can either represent nicked (relaxed circular) DNA that is due to single-strand breaks, or the linear form that is due to double-strand breaks [47] . An example of the nicking assay is shown in Fig. 1,a. The vast majority of the untreated DNA (‘uncut’) was supercoiled. As a positive control, digestion with the restriction enzyme XhoI converted all of the DNA to the linear form as expected. As a positive control for HO˙ generation, FeII+H2O2 resulted in a large decrease in the supercoiled form and a corresponding increase in the nicked form (Fig. 1,a). With this particular plasmid and gel conditions, the linear and nicked forms migrated similarly, but both are indicative of strand breaks. Other reports demonstrated that FeII plus H2O2 generates mostly nicked DNA(single-strand breaks). The increase in strand breaks can be seen in Fig. 1,a. The Cr-induced strand breaks were not affected by the metal chelator diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), but they were significantly diminished by catalase indicating dependence on H2O2 (Fig. 1,a). In accord with this, DTPA only inhibits a minority of the HO˙ generated by this system [18]. Exogenous H2O2 was not included in these experiments because the PLs generate sufficient H2O2 under aerobic conditions to support HO˙ generation [18]. Single-strand breaks increased over time aerobically, and were enhanced by CrVI (Fig. 1,b). In the presence of Cr, the percentage of nicked DNA at 20– 40 min was greater than that at 10 min (P<0.001), and the nicks were greater in the presence of Cr than in its absence (P<0.05). In contrast to aerobic results, DNA nicks were not observed under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 1, c). Aerobically, the PLs generate both CrV and HO˙, but anaerobically they generate CrV but not HO˙ [18]. This indicates that CrV does not have a significant direct role in DNA strand breaks in this system but that HO˙ may have a significant role.

Fig. 1. DNA Strand breaks in pGEM-7Zf(+)during NADPH-dependent CrVI reduction by the PLs.

a) Representative agarose gel of DNA strand breaks resulting from aerobic CrVI reduction. FeII+H2O2 is a positive control for generating HO˙, and ‘XhoI cut’ is a positive control for linearizing DNA. b) and c) Densitometric analysis of the amount of supercoiled vs. nicked DNA over time in the presence or absence of 50 µm CrVI (as Na2CrO4) under aerobic (b) and anaerobic (c) conditions. Reactions (20 µl total volume) were incubated at 37° and included 50 µm Na2CrO4 , PLs (P450 reductase and 0.0152 nmol cytochrome b5), 0.25 µg pGEM-7Zf(+) plasmid DNA, and the NADPH-generating system in Chelex-pretreated buffer (0.15m KCl, 2.5 mm potassium phosphate pH 7.35). Results shown represent the mean ±S.D., n = 3.

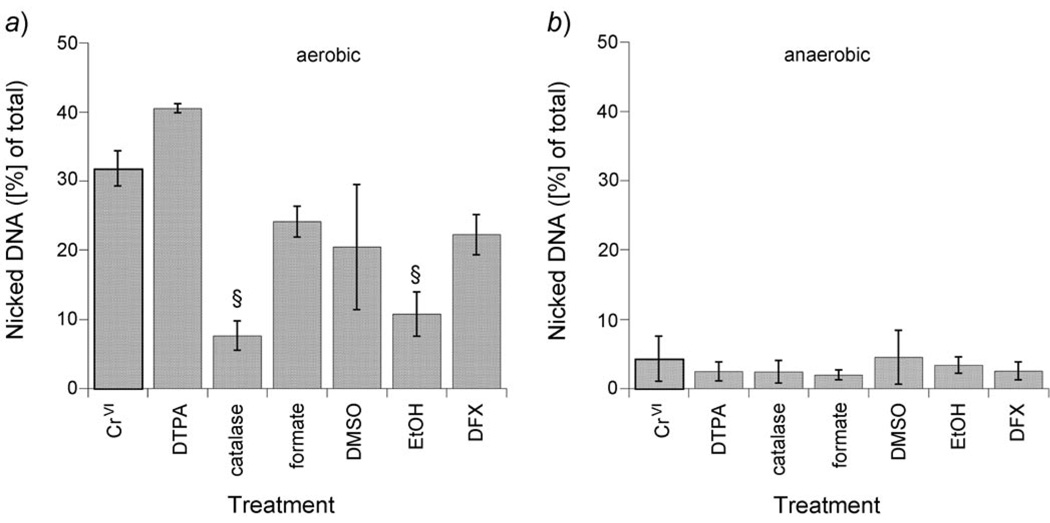

The effects of various chelators and potential antioxidants on the CrVI-mediated DNA strand breaks were examined in triplicate experiments under aerobic (Fig. 2, a) and anaerobic conditions (Fig. 2,b). The chelator DTPA did not decrease the strand breaks. However, both catalase (degrades H2O2) and EtOH (an HO˙ scavenger) markedly inhibited the nicks (Fig. 2, a). These data imply that H2O2-dependent HO˙ generation is largely responsible for the aerobic DNA nicks. Both formate and DMSO, which can also scavenge HO˙, caused a partial decline in the DNA strand breaks, but the declines were not statistically significant (Fig. 2,a). It is possible that they were not as effective at scavenging HO˙ in this system, or that the resulting radicals (CO2˙− and H3C˙, resp.) caused some strand breaks. Deferoxamine (DFX) caused a partial but insignificant decline in strand breaks (Fig. 2,a). In these PLs, it has been shown that CrV chelation by DFX can result in decreased HO˙ generation [18] which could explain the partial decline in DNA nicks. Given the low level of nicks under anaerobic conditions, none of these chelators or antioxidants had a significant effect in anaerobic experiments (Fig. 2,b).

Fig. 2. The effect of various chelators and potential antioxidants on CrVI reduction-mediated DNA nicks under aerobic (a) vs. anaerobic (b) conditions after a 20-min incubation.

Reaction conditions were the same as those in Fig. 1 with the following additions: DTPA (0.1 mm), catalase (500 U), formate (0.25 m), DMSO (5%), EtOH (5%), or DFX (0.25 mm). Results shown represent the mean ±S.D., n = 3. In a), § P≤0.001 compared to CrVI.

When DNA was instead added 60 min after CrVI, at which point nearly all CrVI was reduced to CrIII, DNA strand breaks were not observed (not shown). This implies that CrIII is not involved in the generation of these breaks. This is consistent with the observation that CrIII acetate hydroxide, (AcO)7Cr3(OH)2 , and products of CrIII acetate hydroxide do not cause DNA strand breaks in human lymphocytes whereas CrVI does [30].

A significant role for HO˙ in generating Cr-mediated DNA strand breaks is in agreement with that for some other systems. CrVI Reduction by the NADPH-dependent enzyme glutathione reductase generates HO˙ and DNA strand breaks, and the strand breaks are inhibited by catalase consistent with a role for HO˙ from Cr-mediated Fenton-type chemistry [48]. Catalase similarly inhibited strand breaks in our PLs (Fig. 2). 18 mm H2O2 plus 1.8 mm CrVI causes DNA strand breaks presumably due to HO˙, but CrVI plus GSH does not [29]. GSH plus CrVI yields CrV but does not result in strand breaks, whereas extensive strand breaks are seen when H2O2 is included, implicating HO˙ as a significant mediator of DNA breaks [27] [46]. In mice given dichromate, the resulting DNA breaks were likely due to HO˙ and not CrV [49].

We noted an O2-dependence of the PL-mediated strand breaks (Fig. 1) which corresponds to the conditions under which HO˙ is generated by this system [18]. In some systems, there is an O2-dependence that does not necessarily involve HO˙-mediated strand breaks. For example, strand breaks mediated by a CrV complex with 2-hydroxycarboxylato ligands causes strand breaks in anO2-dependent manner, but there was no diminution of the breaks by catalase [50]. In contrast, a defined CrIV complex, CrIV quinate where quinate is (1R,3R,4R,5R)-1,3,4,5-tetrahydroxycyclohexane carboxylate(2–), can directly cleave DNA independent of O2 [50]. Since we did not observe significant strand breaks anaerobically, it implies that there is not a significant role for CrIV in PL-mediated strand breaks.

In other cases, Cr-mediated strand breaks may not directly involve either CrV or HO˙. For example, with ascorbate-mediated CrVI reduction, the DNA strand breaks are not apparently related to CrV or HO˙, but rather to ascorbyl and carbon radicals [28]. Furthermore, not all CrVI reductants result in DNA strand breaks. Cysteine plus CrVI can generate CrIII-DNA complexes, but fails to generate significant strand breaks [51]. Interestingly, our PLs result in both DNA strand breaks and in CrIII-DNA complexes (see EPR results below).

EPR for CrV

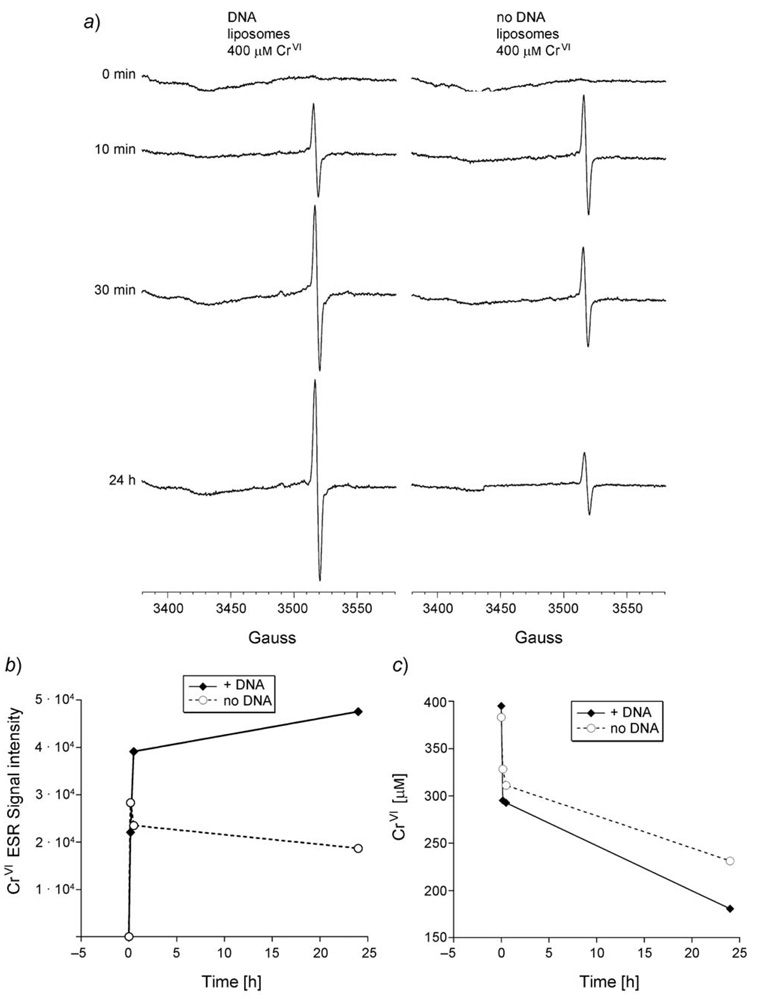

ACrV signal at g = 1.979 was previously reported for the PLs [18], and this signal was observed both in the presence and absence of plasmid DNA (Fig. 3, a). The signal from CrV is readily detectable after 10 min and remains for at least 24 h (Fig. 3,a and b). At 30 min and 24 h, the intensity of the CrV signal was 1.7- and 2.5-fold greater, respectively, in the presence of plasmid DNA (Fig. 3, a and b). It is unknown if the DNA facilitates stabilization of the CrV species, or facilitates continued generation over time. Consistent with the latter possibility, CrVI reduction (i.e., the net decline in CrVI) was greater in the presence of DNA than in its absence (Fig. 3, c). The reason(s) for the effect of DNA on net CrVI reduction are not known, but both in the presence and absence of DNA, the net decline in CrVI was most rapid early and slowed considerably between the 30 min and 24 h interval (Fig. 3, c). This slowdown is not due to CrVI limitation because the CrVI concentration remains well above the Km reported for human microsomal enzymes [52]. It is also not due to NADPH depletion, because the NADPH-generating system maintains a constant level of NADPH over time. A possible explanation for the slowdown is that the enzymes may be potentially damaged by reactive species such as HO˙ over time, and that the presence of plasmid affords some protection for the enzymes by reacting with some of the HO˙. The HO˙-dependent generation of DNA strand breaks (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2) demonstrates that the plasmid DNA does in fact react with some of the HO˙.

Fig. 3.

a) EPR Spectra of CrV obtained during the NADPH-dependent CrVI reduction catalyzed by PLs (37° under room air) in the presence (left) vs. absence (right) of pGEM-7Zf(+) plasmid DNA. The CrV EPR signal intensity (b) and the decline in CrVI (c) in the presence vs. absence of DNA are shown. Reactions (0.3 ml total volume) were incubated at 37° and included 0.4 mm Na2CrO4 , PLs (P450 reductase and 0.0152 nmol cytochrome b5), 7.5 µg plasmid DNA, and the NADPH-generating system in Chelex-treated buffer (0.15m KCl, 2.5 mm potassium phosphate pH 7.35). EPR Instrument settings were: 5 G modulation amplitude, 50 mW microwave power, 6.32 × 104 receiver gain, 40.96 ms time constant, 9.76 GHz microwave frequency, sweep width 200 G, field set 3480 G, modulation frequency 100 kHz, scan time 42 s; number of scans 9.

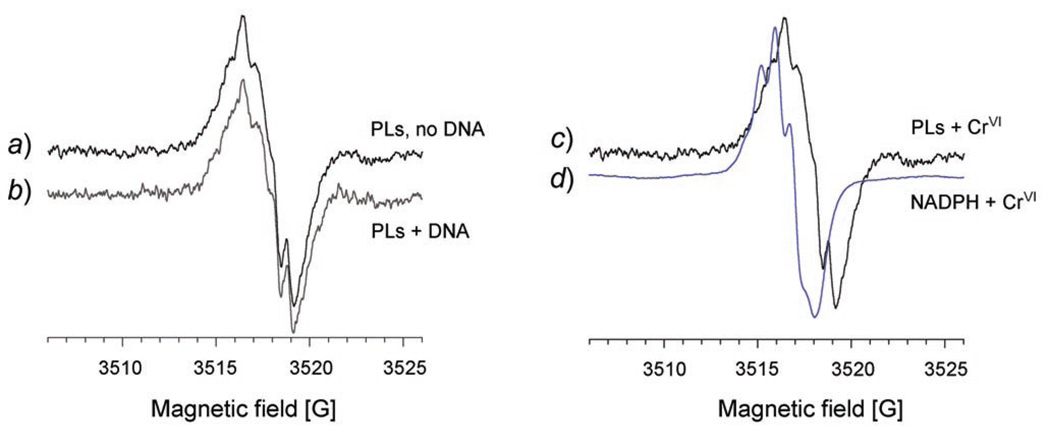

To examine the hyperfine structure of the CrV signal, experiments with PLs were repeated in which the modulation amplitude was reduced to 0.1 G. This greatly diminished the intensity of the CrV signal, so the number of scans was increased to 50. The hyperfine structure of the g = 1.979 CrV signal shows five or six resolved lines, but it also shows that the signals with or without plasmid DNA are not distinguishable (Fig. 4,a and b). The shape of the PLs signal is similar, but not identical, to that for CrV-NADPH (Fig. 4, c and d). The spectra suggest the influence of nearby H-atom in CrV-diol complexes [53]. However, the spectrum for NADPH-CrV was shifted ca. 1 G to the left, suggesting that the predominant signal in the PLs sample is not CrV-NADPH. The spectrum could instead largely result from a complex with glucose-6-phosphate which is present in 35-fold molar excess to NADPH. Several other CrV-diol complexes yield similar spectra including those due to NADH, FAD, and various sugars (fructose, ribose, cellobiose, and others) [53]. While the PLs spectra are different from that for NADPH-CrV, they are not sufficient to provide evidence for CrV-DNA complexes.With ascorbate-mediated CrVI reduction in vitro, CrV may form the initial complexes with DNA, and CrIII-DNA species are formed later by reaction or further reduction of the CrV-DNA [28]. This evidence was based on the observation that Cr was bound to DNA when the ascorbate/Cr ratio favored CrV formation, but not with ratios that favored CrIV and/or CrIII [28]. It is possible that the CrV-DNA species were formed in our system, but that EPR was unable to resolve them from the other species. For example, CrV bound to the phosphates of DNA might also share similarities with that bound to glucose-6-phosphate. Furthermore, the molecular mass of the plasmid (1.85 × 106 Da) is too great to provide for effective averaging of the EPR parameters at room temperature. If a CrV-plasmid complex is formed, the immobilized signal with g‖ and g⊥ would be difficult to detect at room temperature, because it is less intense and superimposed on other signals. At lower temperatures where all the CrV signals are immobilized, two signals with a large ZFS were observed (see below) and are attributed to binding of CrIII to plasmid.

Fig. 4. Hyperfine structure of the g = 1.979 CrV EPR signal.

The spectrum for PLs+CrVI (a) is compared to that with the inclusion of plasmid DNA (b). The reaction conditions were the same as for the previous figure, and the spectra were obtained following 30 min incubation at 37°. The spectrum for PLs+CrVI (c), which is the same as a, is compared to that for NADPH+CrVI (d) (30 min incubation of 5 mm NADPH plus 5 mm Na2CrO4 at 37° in potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). Instrument settings: modulation amplitude 0.1 G, microwave power 50 mW, receiver gain 6.32 × 104, ms time constant 327.68, microwave frequency 9.765 GHz, sweep width 20 G, field set 3516 G, modulation frequency 100 kHz, scan time 83.89 s, and conversion time 81.92 ms. The number of scans was 5 for the NADPH samples and 50 for the others. The y-axis scale for the intensity of each spectrum was adjusted so that the details of the spectra could be conveniently compared on the same plots.

While EPR did not detect CrV-DNA species, it is still possible that they were formed and served as precursors to the final CrIII species. In support of this, g = 5.7and 5.0 CrIII signals were seen in the presence of plasmid DNA but not in its absence (see below). If we incubated CrIIICl3 with the plasmid, we did not see these signals even after 24 h (not shown). Hence, they cannot be formed by the binding of free CrIII to DNA. Thus, they might result from higher valence states of Cr bound to DNA. In agreement with this, Cr–DNA binding is not observed if CrVI is first reduced with ascorbate, and then, the DNA is added later, but binding is observed if the DNA is present during the CrVI reduction process [28]. The prolonged treatment of DNA with CrIIICl3 will lead to some Cr–DNA binding [38], but cannot explain the g = 5.7 and g = 5.0 signals we observed with the PLs plus DNA (below).

EPR for CrIII

shows little direct interaction with DNA [34], and Cr–DNA interactions are minimal with CrVI in the absence of reducing agents [54] [55]. However, CrVI reductants can result in the formation of CrIII-DNA complexes [27] [28] [36] [54].

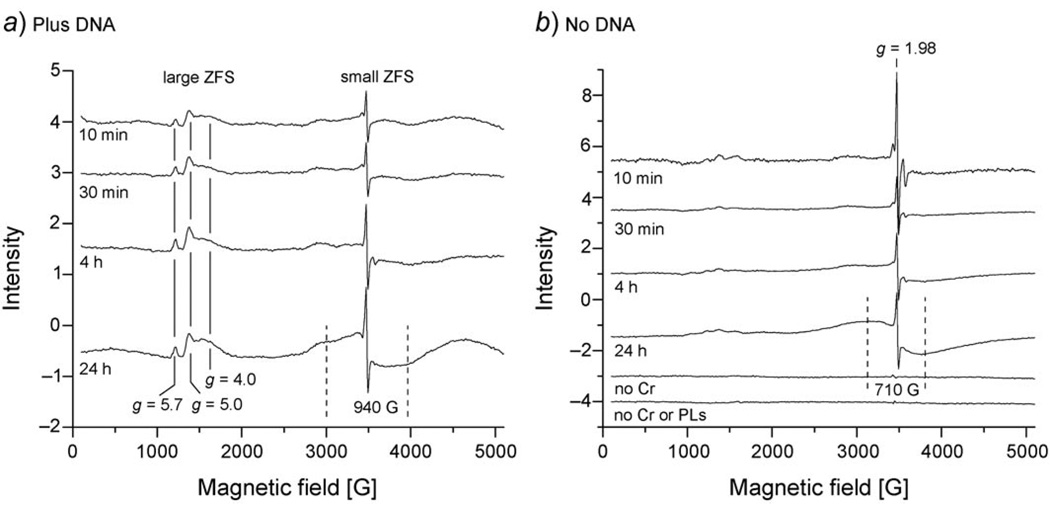

Unlike CrV species which are reactive and transient, CrIII is stable and kinetically inert to ligand substitution [56]. Therefore, CrIII complexes are much more stable and persistent. CrIII EPR signals were examined at lower temperatures (6.3 K) (Fig. 5). In the absence of plasmid, a sharp CrV signal at g = 1.98 and a broader signal (710 G peak to peak) around this CrV signal were observed (Fig. 5,b). This broader signal (Fig. 5,b) increased in intensity over time and represents a CrIII complex or complexes with a small ZFS consistent with near octahedral binding of O-atoms from solvent. This signal was even broader (940 G) in the presence of plasmid (Fig. 5, a), and a shoulder on the low-field side is apparent. The broader linewidth for the signal about g = 2 in the presence of DNA is attributed to CrIII bound to phosphates from the plasmid DNA. Transitions from S = +3/2 to +1/2, +1/2 to −1/2, −1/2 to −3/2, and double quantum transitions are not resolved, suggesting that there are many overlapping non-specific EPR lines from several sites.

Fig. 5. EPR Spectra for CrIII.

The reaction conditions were the same as those indicated in Fig. 3, with PLs incubated with the NADPH-generating system and Na2CrO4 for the indicated times in the presence (a) or absence (b) of plasmid DNA. Following incubation, samples were frozen in liquid N2. Instrument settings: temp. 6.3 K, G modulation amplitude 10, microwave power 16 dB (5 mW), time constant 81 ms, microwave frequency 9.633 GHz, modulation frequency 100 kHz, scan time 83 s; number of scans, 5.

Low-field signals (g(z),eff = 5.7 and 5.0, geff = 4.0) from addition of plasmid DNA to chromate also were observed (Fig. 5,a). These signals are attributed to one or more CrIII site(s) with a large ZFS. The largest value for 2(geff/g) from a rhombogram is 5.46 for the S = +/−1/2 transition [57] . The line with geff = 5.7is assigned to a S = +/−3/2 transition. E/D (the ratio of E to D, which are the axial and rhombic zero-field splitting parameters, resp.) is 0.22 from the rhombogram indicating substantial distortion from cubic symmetry. The signal at g = 4 is due to a second species. These Cr signals are much like the signals observed for CoII-substituted horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, another S = 3/2 spin system [58]. The concentration of the signal with the large ZFS is ca. 7 µm as determined by simulating the signal (g(z)eff = 5.0, g(y)eff = 2.6, g(x)eff = 1.7,where g(y)eff and g(x)eff are too broad to detect or superimposed by other signals in the experimental spectrum and g = 1.98) and comparison of the simulated signal with the signal from a cupric standard (data not shown). Using this approximation, the ratio of Cr (g(z)eff = 5.0) with a large ZFS to bp of plasmid is 1 Cr per 4.3 bp. Since the large ZFS signals (g = 5.7 and 5.0) appear early and do not increase appreciably over time, it is assumed that the binding is saturated. This is consistent with the observation that CrIII preferentially binds to guanine residues [34], and 25% of the residues in pGEM-7Zf(+) are guanine.

Analogous experiments were conducted substituting commercially available calf thymus DNA for plasmid DNA. However, the CrIII signals with a large ZFS that were observed with the plasmid DNA were not detected in the presence of calf thymus DNA (spectrum not shown). The reason(s) for the difference are not clear. However, plasmid DNA can bind several-fold more CrIII than calf thymus DNA [34] [59], which could explain the absence of the CrIII EPR signals with calf thymus DNA. The pGEM-7Zf(+) plasmid has a higher GC content (49.9%) than does calf thymus DNA (42%), which may explain a minority of the differences in Cr binding and EPR spectra. Other possible contributing factors to the different results with these DNAs include: a) the plasmid is circular, whereas the calf thymus is linear DNA; b) mutational analyses suggest the possibility of preferential sites for CrIII-DNA adducts [59], and it is possible that calf thymus DNA has a lower percentage of such sites; c) the plasmid DNA has a much smaller mass than the thymus DNA which might contribute to different overall structure or conformation in solution; and d) eukaryotic DNA is typically associated with tightly associated proteins, which could have limited the ability of calf thymus DNA to interact with Cr. Overall, however, it is concluded that EPR can be used to detect various CrIII species that are dependent on the presence of plasmid DNA. Further characterization of these DNA-dependent CrIII signals may provide insights into the possible nature of the species, and if they are potentially detrimental to cells or DNA structure and function.

Experimental Part

General

Purified recombinant human cytochrome b5 and P450 reductase, and the restriction enzyme XhoI were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). l-α-Phosphatidylcholine, hydrogenated, egg yolk (cat. no. 840059): Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL); sodium cholate: Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA); (phenylmethyl)sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and Tris: Research Organics (Cleveland, OH). Sodium chromate (>99%) was the highest purity available from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, WI). Chromates are known carcinogens and should be handled accordingly. Other chemicals obtained from Aldrich were activated aluminum oxide, activated carbon, and 1,5-diphenylcarbazide. Ferrous ammonium sulfate and H2O2 : Mallinckrodt Chemicals (Phillipsburg, NJ); H2SO4 : J. T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ); NaCl: VWR Scientific (West Chester, PA); EDTA: Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH); catalase (cat. no. C100): Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). This catalase has been shown to be free from inherent CrVI-reducing activity [18]. Other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical. Plasmid DNA (pGEM®-7Zf(+)) was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI); seakem LE agarose was from Cambrex, and ethidium bromide was from EMD Chemicals (Germany).

Purification and Preparation of DNA

Escherichia coli JM109 containing pGEM®-7ZF(+) plasmid was grown overnight at 37° in Luria-Bertani medium pH 7.4 [60] supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/ml). Plasmid DNA was purified from these cells using the HiSpeed® Plasmid Midi Kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Before use, the purified DNA was treated with the chelator DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) to remove possible metal contaminants. DNA was dialyzed for 3 h at 4° against 1 mm DTPA in Chelex pre-treated 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.35) using Slide-A-Lyzer® mini dialysis units (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The DNA was then extensively dialyzed against DTPA-free buffer. DNA Concentration was determined from its UV absorbance at 260 nm, and DNA purity was determined from the ratio of absorbances at 260 and 280 nm.

Preparation of Proteoliposomes

Proteoliposomes (PLs) containing purified human P450 reductase plus cytochrome b5 were reconstituted using a cholate dialysis procedure as described in [18]. They were stored at 4° and used as soon as possible (usually within 1 d) for the experiments. The ability of NADPH:P450 reductase to efficiently transfer electrons to cytochrome b5 was confirmed by cytochrome spectral analysis as described in [18]. The amount of PLs used for each experiment was normalized to the b5 content as determined from these spectra.

General Procedures

Experiments under anaerobic conditions were conducted in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake,MI; 4 to 5% H2 , balance N2) as described in [52]. Solns. were pre-incubated in the anaerobic chamber before use. CrVI reduction rates under these conditions were found to be indistinguishable from those in which the vials were made anaerobic by flushing with O2-free N2 [52]. Experiments under aerobic conditions were conducted in open-top vials under room air.

To remove polyvalent metal ion contaminants, solns. were pretreated with Chelex-100 (5 g per 100 ml soln.) for at least 1 h before use.

The general reaction conditions for the proteoliposome experiments were as follows: the buffer (0.15m KCl, 2.5 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.35), and NADPH-generating mix [52] were pre-incubated for 5 min at 37°. The PLs, Na2CrO4 , and DNA (when included) were added, followed by incubation at 37° for the indicated times. The reactions were then analyzed by EPR or for CrVI as indicated below. Variables in each experiment (time, DNA, Cr concentration) are indicated in the results.

For quant. data, differences between multiple groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA and the Tukey–Kramer post test (InStat software, GraphPad). Significance was assumed at P<0.05.

CrVI Assay

In some experiments, a colorimetric assay was used to determine the CrVI concentration at fixed time points. The complete details of this 1,5-diphenylcarbazide colorimetric assay as applied to human enzymatic CrVI reduction were described in [17] . The only differences here were that the incubation buffer (0.15m KCl/2.5 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.35) was treated with Chelex-100 resin prior to use, and that PLs were substituted for microsomes. Volumes of all reagents were scaled down proportionally to accommodate smaller total reaction volumes.

DNA Strand Break Assay

The ability of the PL-mediated reduction of CrVI to generate DNA strand breaks was determined using the plasmid nicking assay as adapted from Fitzsimmons et al. [47] . pGEM-7Zf(+) Plasmid DNA was included in the reactions at the concentrations indicated in the results. The reactions were stopped by the addition of stop buffer (0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 mm EDTA, 60% glycerol, 0.1% bromphenol blue). Aliquots of the reactions were then loaded onto a 0.6% agarose gel (in Tris/acetate/EDTA buffer) and electrophoresed for 40 min at 120 V. The DNA was visualized with the dye ethidium bromide (2 µg/ml). The gels were photographed on a UV transilluminator (302 nm) using a filter appropriate for ethidium bromide. The relative abundance of the supercoiled vs. nicked forms were determined by densitometric analysis of the gel images using UN-SCAN-IT software (Version 6.1, Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

EPR for CrV and CrIII

The reactions were stopped by immersion in liq. N2 (77 K), and the samples were stored in quartz EPR tubes at 77 K, typically for less than one week. For some samples, spectra for CrIII were first obtained at liq. He temp. (6.3 K) using a Bruker E500 ELEXSYS spectrometer (Silberstreifen, Germany) with an Oxford Instruments ESR-9 He flow cryostat (Oxfordshire, UK) and a Bruker DM0101 cavity. For CrV EPR, samples were quickly thawed, placed in a quartz flat cell, and ESR spectra were obtained without delay at r.t. using a Bruker EMX spectrometer. The spectra were stable during the ESR analysis time, with no noticeable changes in spectral intensity or pattern. Instrument settings are indicated in the results. ESR Spectra were confirmed in replicate experiments. The g values were determined by comparison to the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) which has a g value of 2.0036.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant number ES012707 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NIH. The ESR facilities of the Department of Biophysics are supported by National Biomedical ESR Center, Grant EB001980 from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Environmental Protection Agency. Chromium, Integrated Risk Information System, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Washington, D. C: EPA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gadd GM, White C. TIBTECH. 1993;11:353. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(93)90158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhitkovich A, Voitkun V, Kluz T, Costa M. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998;106 suppl. 4:969. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kortenkamp A, Beyersmann D, O’Brien P. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 1987;14:23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buttner B, Beyersmann D. Xenobiotica. 1985;15:735. doi: 10.3109/00498258509047435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantoni O, Costa M. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:1207. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.9.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christie NT, Cantoni O, Evans RM, Meyn RE, Costa M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984;33:1661. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy LS, Venitt S. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:831. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsapakos MJ, Hampton TH, Wetterhahn KE. Cancer Res. 1983;43:5662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting RF, Stich HF, Koropatnick DJ. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1979;26:267. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(79)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Standeven AM, Wetterhahn KE. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:1319. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.8.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikalsen A, Alexander J, Ryberg D. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1989;69:175. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennette KW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:874. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi X, Dong Z, Dalal NS, Gannett PM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1226:65. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi XL, Dalal NS. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1990;40:1. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(90)80034-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki Y, Fukuda K. Arch. Toxicol. 1990;64:169. doi: 10.1007/BF02010721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt PF, Myers CR. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:2051. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.10.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borthiry GR, Antholine WE, Kalyanaraman B, Myers JM, Myers CR. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2007;42:738. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Standeven AM, Wetterhahn KE. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1991;4:616. doi: 10.1021/tx00024a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon CT, Lay PA, Bonin AM, Cholewa M, Legge GJF, Collins TJ, Kostka KL. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998;11:119. doi: 10.1021/tx9701541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi X, Chiu A, Chen CT, Halliwell B, Castranova V, Vallyathan V. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part B. 1999;2:87. doi: 10.1080/109374099281241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi X, Dalal NS. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;292:323. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90085-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi X, Ding M, Ye J, Wang S, Leonard SS, Zang L, Castranova V, Vallyathan V, Chiu A, Dalal N, Liu K. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;75:37. doi: 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers CR, Myers JM, Carstens BP, Antholine WE. Toxic Subst. Mech. 2000;19:25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jannetto PJ, Antholine WE, Myers CR. Toxicology. 2001;159:119. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levina A, Zhang L, Lay PA. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:767. doi: 10.1021/ic020621o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aiyar J, Borges KM, Floyd RA, Wetterhahn KE. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 1989;22:135. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stearns DM, Kennedy LJ, Courtney KD, Giangrande PH, Phieffer LS, Wetterhahn KE. Biochemistry. 1995;34:910. doi: 10.1021/bi00003a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawanishi S, Inoue S, Sano S. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao M, Binks SP, Chipman JK, Levy LS, Braithwaite RA, Brown SS. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1992;11:77. doi: 10.1177/096032719201100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugiyama M. Environ. Health Perspect. 1991;92:63. doi: 10.1289/ehp.919263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cupo DY, Wetterhahn KE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:6755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Wise JP, Patierno SR. Mutat. Res. 1992;280:129. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(92)90008-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arakawa H, Ahmad R, Naoui M, Tajmir-Riahi HA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugden KD. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;77:177. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridgewater LC, Manning FCR, Patierno SR. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2421. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.11.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snow ET, Xu L-S. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11238. doi: 10.1021/bi00111a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bridgewater LC, Manning FC, Woo ES, Patierno SR. Mol. Carcinog. 1994;9:122. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi X, Dalal NS. FEBS Lett. 1990;276:189. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80539-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsou T-C, Yang J-L. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1996;102:133. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(96)03740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsou T-C, Chen C-L, Liu T-Y, Yang J-L. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:103. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi X, Mao Y, Knapton AD, Ding M, Rojanasakul Y, Gannett PM, Dalal N, Liu K. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2475. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.11.2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo H, Lu Y, Shi X, Mao Y, Dalal NS. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1996;26:185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weeks CL, Levina A, Dillon CT, Turner P, Fenton RR, Lay PA. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:7844. doi: 10.1021/ic049008q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molyneux MJ, Davies MJ. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:875. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.4.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aiyar J, Berkovits HJ, Floyd RA, Wetterhahn KE. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1990;3:595. doi: 10.1021/tx00018a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitzsimmons SA, Lewis AD, Riley RJ, Workman P. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1503. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.8.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leonard SS, Vallyathan V, Castranova V, Shi X. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;234–235:309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueno S, Kashimoto T, Susa N, Furukawa Y, Ishii M, Yokoi K, Yasuno M, Sasaki YF, Ueda J, Nishimura Y, Sugiyama M. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2001;170:56. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levina A, Barr-David G, Codd R, Lay PA, Dixon NE, Hammershøi A, Hendry P. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:371. doi: 10.1021/tx980229g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhitkovich A, Quievryn G, Messer J, Motylevich Z. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110 Suppl. 5:729. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myers CR, Myers JM. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1029. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi X, Dalal NS. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;277:342. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90589-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsapakos MJ, Wetterhahn KE. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1983;46:265. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(83)90034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hneihen AS, Standeven AM, Wetterhahn KE. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:1795. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.9.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manning FCR, Xu J, Patierno SR. Mol. Carcinog. 1992;9:122. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940060409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hagen WR. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 1992;38:165. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Werth MT, Tang S-F, Formicka G, Zeppezauer M, Johnson MK. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:218. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsou TC, Lin RJ, Yang JL. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:962. doi: 10.1021/tx970040p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T, editors. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]