Abstract

One case of recurrent multifocal central giant cell granulomas (CGCG) is presented. Initially, the lesions presented concurrently in the maxilla and mandible with subsequent recurrence in the mandible. Now, two recurrences are seen in the maxillary sinus and ethmoid region. The literature regarding multifocal CGCG is reviewed.

Keywords: Central giant cell granulomas (CGCG), Reparative giant cell granuloma, Craniofacial giant cell dysplasia

Introduction

The central giant cell granuloma (CGCG) affects females more often than males, in a 2:1 ratio and is seen most frequently under the age of 30 years [1]. One study of 38 patients shows 74% to be less than 30 years of age and 61% to be less than 20 years of age [2]. The lesion commonly presents as a solitary radiolucency with a multilocular appearance or less commonly, a unilocular appearance [2–4]. It is more prevalent in the anterior than the posterior jaws, often crossing the midline, and the mandible is more commonly affected than the maxilla [2, 4]. This lesion has also been reported in the small bones of the hands and feet [5, 6]. The behavior of CGCG is variable, most commonly producing asymptomatic expansion of the jaws [7]. However, it can be clinically aggressive, associated with pain, osseous destruction, cortical perforation, root resorption, and recurrence [8]. Cases of CGCG occurring with neurofibromatosis (type 1) [7, 9–11], Noonan-like syndrome [12, 13], or both [7, 14] have been reported.

The treatment of CGCG includes simple curettage or curettage with peripheral ostectomy; Resection for lesions of the maxilla or paranasal sinuses has been advocated as the thin bony cortices and sinuses do not provide a good anatomic barrier [15]. Corticosteroids and calcitonin are used for non-surgical management [16, 17]. Interferon alpha therapy has also been used as a postoperative adjuvant and to prevent tumor progression [18, 19].

Report of a Case

This patient’s histological slides were referred to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center for pathology consultation. Her medical records were subsequently obtained. The patient was a 42-year-old female with a history of multifocal giant cell lesions in the left mandible and left maxilla. A year after her initial diagnosis and treatment, a recurrent lesion was noted in the left mandible and subsequently curetted. Two and a half years after the initial lesions, this was the second recurrent episode. This recurrence, the patient presented with two distinct lesions the larger, inferior lesion filling much of the maxillary sinus and the smaller, superior lesion adjacent to the ethmoid region. A comprehensive laboratory assessment to rule out hyperparathyroidism revealed: calcium (serum) 9.8 (normal 8.5–10.4 mg/dl), PTH (intact) 58 pg/ml (normal 12–65 pg/ml), phosphorus (serum) 2.9 mg/dl (normal 2.5–4.5 mg/dl), albumin 5.1 (normal 3.7–5.1 g/dl), urine calcium level of 6.4 mg/dl (normal, not established), and urine 24 h calcium 185.4 mg/24 h (normal 100.0–300.00 mg/24 h). Other laboratory values were within normal limits, except for a bilirubin of 1.8 mg/dl (normal 0.1–1.2 mg/dl). The patient had known Gilbert’s syndrome.

The patient’s clinical appearance was phenotypically normal, not that of Noonan’s syndrome. Although we are uncertain what testing was performed, a comprehensive workup revealed the patient was negative for Noonan’s syndrome and hyperparathyroidism.

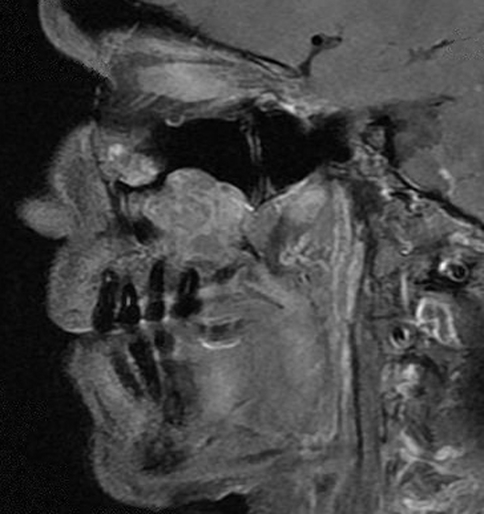

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), two lesions were seen (see Fig. 1). The lesions were heterogeneously hyperintense on T2 weighted imaging and isointense to brain on T1 weighted imaging with enhancement. The larger of the two recurrent lesions was 3.1 × 2.9 × 2.6 cm encompassing the roots of the maxillary posterior teeth and deviating the inferior turbinate (see Fig. 2). The second lesion was 2.4 × 2.3 × 2.1 cm and was located inferior to the medial floor of the left orbit. Invasion of the medial wall of the left maxillary sinus with bulging into the nasal cavity and thinning of the posterolateral maxillary sinus wall with tumor bulging into the retromaxillary fat pad was seen.

Fig. 1.

T1 weighted MRI of the tumors on sagittal section demonstrating proximity to the dentition and the ethmoid region

Fig. 2.

T2 weighted MRI of the larger inferior lesion on coronal section demonstrating deviation of inferior turbinate

A left endoscopic ethmoidectomy was performed using an image guidance mask. The recurrent left maxillary giant cell granuloma (GCG) was excised via intraoral approach. The maxillary lesion was removed, followed by stripping of the maxillary sinus mucosa to bone. The maxillary sinus was reconstructed with demineralized bone matrix and autogenous platelet rich plasma.

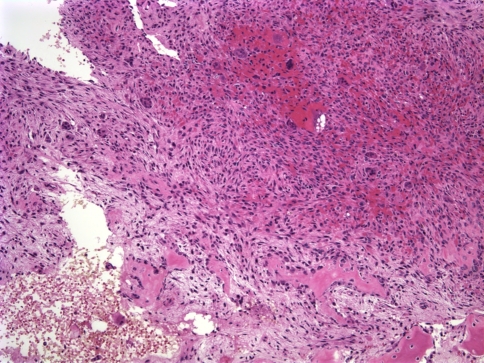

The two pathology specimens from the left ethmoid region and maxillary sinus were histologically similar, revealing abundant diffusely distributed multinucleated central giant cells (see Fig. 3). The hypercellular fibrous stroma was composed of mononuclear spindle shaped cells and scattered ovoid cells. Cystic areas of extravasated nonendothelialized hemorrhage, resembling an aneurysmal bone cyst, and minimal mitotic activity were observed but no cellular atypia was observed.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph from first recurrence of the left maxillary CGCG showing multinucleated giant cells in a spindle or ovoid shaped fibrovascular connective tissue stroma (H&E, ×10)

Discussion

Much controversy surrounds the CGCG. Initially, it was not distinguished from the giant cell tumor of the extragnathic skeleton [20], but later it was described by Jaffe as the giant cell reparative granuloma [21]. Some authorities advocate using the more neutral term “central giant cell lesion” to describe this process, but most accept CGCG. CGCG has been proposed to be both a reactive response, to hemorrhage or trauma, and a neoplasm [2, 3, 22]. Some have proposed that giant cell granuloma of the jaws and giant cell tumors (GCT) of the extragnathic skeleton are part of a spectrum of a single lesion, modified by anatomic site [2, 15]. However, others have viewed CGCGs and GCTs of the extragnathic skeleton as distinct lesions [21, 23, 24]. Certain histological differences exist between the CGCG and the GCT (see Table 1). The giant cells are more evenly distributed in the GCT, focal areas of necrosis exist, decreased fibrous tissue is present, and an accumulation of inflammatory cells may be seen [25]. Histologically, CGCG resembles the giant cell lesion of hyperparathyroidism, cherubism, and aneurysmal bone cyst, which must be excluded. Multiple central giant cell lesions have been reported in association with Noonan-like/multiple giant cell lesion syndrome, and other features of the disease include a short stature, webbed neck, cubitus valgus, pulmonic stenosis, and multiple lentigenes [26].

Table 1.

Comparison of giant cell tumor and central giant cell granuloma

| Giant cell tumor | Central giant cell granuloma | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Sphenoid, temporal, ethmoid bones (endochondral ossification, not membranous in origin) Jaws in paget disease |

Jaws, anterior mandible |

| Giant cells | Evenly distributed | Fewer, smaller giant cells, unevenly distributed |

| Stromal cells | Monocytes, osteoclasts No intercellular collagen |

Fibroblasts producing collagen; Numerous capillaries |

| Osteoid | No | Yes |

Immunohistochemical studies on CGCG have helped establish the lineage of the cells, but not to predict the aggressiveness of the lesion. Supporting the theory that the multinucleated giant cells are derived from macrophages is the immunoreactive response to muramidase, α-1 antichymotrypsin, and α-1 antitrypsin [27]. Aggressive and non-aggressive CGCGs stained for antibodies to CD34, CD68, factor Xllla, and smooth muscle actin, prolyl 4-hydroxylase, Ki-67, p53 protein, RANK, and glucocorticoid receptor alpha have revealed no phenotypic differences between the types [28, 29]. Calcitonin receptor expression, however, has been found to exhibit a statistically significant difference with more expression in the aggressive type [29]. Immunohistochemical staining for c-Src, a protein thought to be required for osteoclast activation, has yielded no quantitative difference between CGCG, GCT, or cherubism [30]. The SH3BP2 gene is commonly found to be mutated in cherubism, and its transcripts and proteins have been found to be expressed in GCT and CGCG. [31] The mononuclear stromal cells display strong p63 immunostaining in GCTs, but this has not been detected in CGCGs [32, 33]. Thus, P63 is one immunohistochemical stain that may help distinguish GCT from CGCG, while also suggesting a differing pathogenesis.

Multifocal CGCG is a challenging entity. In previous reviews of the literature, different cases have been included as multifocal CGCG [34, 35]. Previous cases of multiple giant cell lesions may represent:

Association with a syndrome or genetic condition [14, 15, 38]

A single lesion of a jaw separated by normal bone

Association with elevated PTHrP [39]

True giant cell tumors originating in the maxillofacial region,

Multifocality resulting from hematogenous spread due to inadequate treatment

In total, we believe there are six convincing cases of multifocal CGCG of the maxillofacial skeleton previously reported and not better explained by other pathologic conditions (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of multifocal central giant cell granulomas

| Reference | Age/Sex | Location at initial presentation | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Davis and Tideman [43] | 31/F | R mandibular body | 4 months L maxilla 1 year L maxilla 2 years R mandible |

| Smith et al. [40] | 41/F | R mandibular angle | 9 years L maxillary sinus, nasal bone, orbital floor and R maxillary sinus |

| Martins et al. [35] | 35/F | L maxilla R mandible |

5 years follow-up no recurrence |

| Loukota [44] | 25/F | R mandible | 10 months L maxilla No additional recurrence at 2 years |

| Wise and Bridebord [45] | 23/M | L mandibular body L and R nasomaxillary area |

4 years follow-up no recurrence |

| Miloro and Quinn [34] | 37/F | L maxilla Ant. mandible |

1 year L maxilla and ant mandible |

| Bilodeau, Chowdhury, and Collins | 42/F | L mandible L maxilla |

1 year L mandible 2 years L maxillary sinus/ethmoid region |

Smith et al. [40] have proposed a new term, “craniofacial giant cell dysplasia,” to describe the multifocal central giant cell of the jaws. Miloro and Quinn [34] advocate dividing multifocal central giant cell lesions into synchronous or metachronous lesions. They propose metachronous lesions are more likely to represent a recurrence due to inadequate initial treatment or tumor seeding, whereas synchronous lesions are more likely to represent true multifocality.

Our case represents a clinically aggressive, multifocal, and recurrent CGCG that is quite bland histologically, and not associated with other conditions or syndromes. It displays a secondary aneurysmal bone cyst component seen in 30% of CGCG [41] as well as other osseous lesions [42]. Given the small number of cases available, it is difficult to draw any conclusions. However, some trends may be observed. Similar to CGCG, there was a female predominance, representing six of the seven patients. Slightly older populations than in most CGCGs were seen. The mean age in our review of published multifocal cases was 33 years, with only two of the seven patients younger than 30 years of age. It is possible that occult or inadequately treated CGCGs spread hematogenously, but this is not a traditional characteristic behavior of these lesions. Multifocal CGCGs are more aggressive than solitary CGCGs as exhibited by increased recurrence and osseous destruction. They should be treated with more aggressive surgical therapy as in five of seven cases the patients had a recurrence.

Central giant cell granuloma remains a challenge for pathologists. There are multiple conditions that must be ruled out clinically, and the controversy surrounding the etiology of this condition has yet to be definitively resolved.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Leon Barnes, Simion Chiosea, and Raja Seethala for their comments on this paper.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Bilodeau, Email: rodeea@upmc.edu.

Khalid Chowdhury, Email: craniofacial@qwestoffice.net.

Bobby Collins, Email: bcollins@dental.pitt.edu.

References

- 1.Motamedi MH, Eshghyar N, Jafari SM, et al. Peripheral and central giant cell granulomas of the jaws: a demographic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldron CA, Shafer WG. The central giant cell reparative granuloma of the jaws: an analysis of 38 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:437–447. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/45.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitaker SB, Waldron CA. Central giant cell lesions of the jaws: a clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90094-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaffe I, Ardekian L, Taicher S, et al. Radiologic features of central giant cell granuloma of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:720–726. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzo JC, Dorfman HD. Giant-cell reparative granuloma of short tubular bones of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:551–563. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glass TA, Mills SE, Fechner RE, et al. Giant-cell reparative granuloma of the hands and feet. Radiology. 1983;149:65–68. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.1.6611953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange J, Akker HP. Clinical and radiological features of central giant-cell lesions of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruse-Losler B, Diallo R, Gaertner C, et al. Central giant cell granuloma of the jaws: a clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic study of 26 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ardekian L, Manor R, Peled M, et al. Bilateral central giant cell granulomas in a patient with neurofibromatosis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:869–872. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90833-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggieri M, Pavone V, Polizzi A, et al. Unusual form of recurrent giant cell granuloma of the mandible and lower extremities in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:67–72. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards PC, Fantasia JE, Saini T, et al. Clinically aggressive central giant cell granulomas in two patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:765–772. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MM, Jr, Gorlin RJ. Noonan-like/multiple giant cell lesion syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1991;40:159–166. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancino CM, Gaiao L, Sant’Ana Filho M, et al. Giant cell lesions with a Noonan-like phenotype: a case report. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damme PA, Mooren RE. Differentiation of multiple giant-cell lesions, Noonan-like syndrome, and (occult) hyperparathyroidism: case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;23:32–36. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stolovitzky JP, Waldron CA, McConnel FMS. Giant cell lesions of the maxilla and paranasal sinuses. Head Neck. 1994;16:143–148. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880160207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terry BC, Jacoway JR. Management of central giant cell lesions: an alternative to surgical therapy. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1994;6:579–600. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange J, Akker HP, Veldhuijzen van Zanten GO, et al. Calcitonin therapy in central giant cell granuloma of the jaw: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:791–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange J, Akker HP, Berg H, et al. Limited regression of central giant cell granuloma by interferon alpha after failed calcitonin therapy: a report of 2 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:865–869. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaban LB, Troulis MJ, Ebb D, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy with interferon alpha for giant cell lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:1103–1111. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.34975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernick S. Central giant cell tumors of the jaws. J Oral Surg. 1948;6:324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffe H. Giant cell reparative granuloma, traumatic bone cyst, and fibrous (fibro-osseous) dysplasia of the jaw bones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6:159–175. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(53)90151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shklar G, Meyer I. A giant-cell tumor of the maxilla in an area of osteitis deformans (Paget’s disease of bone) Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1958;11:835–842. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(58)90198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin L, Dahlin D, Royer R. Giant-cell reparative granuloma and related conditions affecting the jawbones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1959;12:1285–1295. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(59)90215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrams B, Shear M. A histological comparison of the giant cells in central giant cell granuloma of the jaws and the giant cell tumor of long bone. J Oral Pathol. 1974;3:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1974.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auclair PL, Kratochvil FJ, Slater LJ, et al. A clinical and histomorphologic comparison of the central giant cell granuloma and giant cell tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen MM, Jr, Gorlin RJ. Noonan-like/multiple giant cell lesion syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1991;40:159–166. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regezi JA, Zarbo RJ, Lloyd RV. Muramidase, alpha-1 antitrypsin, alpha-1 antichymotrypsin, and S-100 protein immunoreactivity in giant cell lesions. Cancer. 1987;59:64–68. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870101)59:1<64::AID-CNCR2820590116>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Malley M, Pogrel MA, Stewart JC, et al. Central giant cell granulomas of the jaws: phenotype and proliferation-associated markers. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobon-Arroyave SI, Franco-Gonzalez LM, Isaza-Guzman DM, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of RANK, GRalpha and CTR in central giant cell granuloma of the jaws. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Song Y, Peng B, et al. Expression of c-Src and comparison of cytologic features in cherubism, central giant cell granuloma and giant cell tumors. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lietman SA, Prescott NL, Hicks DG, et al. SH3BP2 is rarely mutated in exon 9 in giant cell lesions outside cherubism. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;459:22–27. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31804b4131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee CH, Espinosa I, Jensen KC, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies p63 as a diagnostic marker for giant cell tumor of the bone. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:531–539. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickson BC, Li SQ, Wunder JS, et al. Giant cell tumor of bone express p63. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:369–375. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miloro M, Quinn PD. Synchronous central giant cell lesions of the jaws: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:1350–1355. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martins WD, Oliveira Ribas M, Braosi AP, et al. Multiple giant cell lesions of the maxillofacial skeleton. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1250–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cassatly MG, Greenberg AM, Kopp WK. Bilateral giant cell granulomata of the mandible: report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;117:731–733. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1988.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weldon L, Cozzi G. Multiple giant cell lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982;40:520–522. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(82)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis NJ, Walker DM. A case of aggressive multiple metachronous central giant cell granulomas of the jaws: differential diagnosis and management options. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:806–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis JP, Archer DJ, Fisher C, et al. Multiple recurrent giant cell lesions associated with high circulating levels of parathyroid hormone-related peptide in a young adult. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:102–105. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90092-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith PG, Marrogi AJ, Delfino JJ. Multifocal central giant cell lesions of the maxillofacial skeleton: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:300–305. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90398-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Struthers PJ, Shear M. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the jaws. (II). Pathogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13:92–100. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(84)80078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy W, Miller A, Bonakdarpour A, et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst secondary to other osseous lesions: report of 57 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975;63:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/63.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis GB, Tideman H. Multiple recurrent central giant cell granulomas of the jaws. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977;5:127–129. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(77)80089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loukota RA. Metachronous and recurrent central giant cell granulomas: a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:48–50. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wise AJ, Bridbord JW. Giant cell granuloma of the facial bones. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;30:564–568. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199306000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]