Abstract

The activation and recruitment of CD4+ T cells are critical for the development of efficient antitumor immunity and may allow for the optimization of current cancer immunotherapy strategies. Searching for more optimal and selective targets for CD4+ T cells, we have investigated phosphopeptides, a new category of tumor-derived epitopes linked to proteins with vital cellular functions. Although MHC I-restricted phosphopeptides have been identified, it was previously unknown whether human MHC II molecules present phosphopeptides for specific CD4+ T cell recognition. We first demonstrated the fine specificity of human CD4+ T cells to discriminate a phosphoresidue by using cells raised against the candidate melanoma antigen mutant B-Raf or its phosphorylated counterpart. Then, we assessed the presence and complexity of human MHC II-associated phosphopeptides by analyzing 2 autologous pairs of melanoma and EBV-transformed B lymphoblastoid lines. By using sequential affinity isolation, biochemical enrichment, mass spectrometric sequencing, and comparative analysis, a total of 175 HLA-DR-associated phosphopeptides were characterized. Many were derived from source proteins that may have roles in cancer development, growth, and metastasis. Most were expressed exclusively by either melanomas or transformed B cells, suggesting the potential to define cell type-specific phosphatome “fingerprints.” We then generated HLA-DRβ1*0101-restricted CD4+ T cells specific for a phospho-MART-1 peptide identified in both melanoma cell lines. These T cells showed specificity for phosphopeptide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells as well as for intact melanoma cells. This previously undescribed demonstration of MHC II-restricted phosphopeptides recognizable by human CD4+ T cells provides potential new targets for cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: tumor antigen, tumor immunology

Immunotherapies directed against currently defined tumor-associated or tumor-specific antigens can enhance antitumor immunity in patients, as detected with in vitro immune monitoring, and yet they have had limited clinical success (1). One reason may be the nature of the targeted antigens, the majority of which are proteins overexpressed in tumor cells but not essential to maintaining their malignant phenotype.

Phosphorylation is the most common and ubiquitous form of enzyme-mediated posttranslational protein modification, and transient phosphorylation of intracellular signaling molecules regulates cellular activation and proliferation (2). Phosphorylation cascades are often dysregulated during malignant transformation, leading to uncontrolled proliferation, invasion of normal tissues, and distant metastasis (3, 4). Limited but growing evidence has shown that tumor-associated phosphoproteins processed intracellularly through an endogenous pathway can give rise to phosphopeptides complexed to MHC I molecules, which are displayed on the cell surface (5, 6). CD8+ T cells immunized to specifically recognize these phosphopeptides are also capable of recognizing intact human tumor cells, suggesting that phosphopeptides may represent a new class of targets for cancer immunotherapy (5, 6). In these studies and others, T cell discrimination of the phosphopeptide versus its nonphosphorylated counterpart was observed, indicating that phosphorylation can influence peptide immunogenicity (5–13). Recent crystal structural definition of phosphorylated peptide–HLA-A2 complexes demonstrated direct and indirect interactions of the phosphoresidue with the MHC molecule, often significantly increasing the affinity of the phosphopeptide for MHC I. Additionally, phosphoresidues were solvent-exposed, suggesting the potential for direct interactions with the T cell receptor (14, 15).

Mounting evidence indicates that MHC II-restricted CD4+ T lymphocytes are a critical component of antitumor immunity, and their activation and recruitment may be required to optimize cancer immunotherapies (16, 17). A variety of posttranslational modifications have been identified on naturally processed MHC class II-associated epitopes. These include N- and O-linked glycosylation, N-terminal acetylation, nitration, deamidation, and deimination/citrullination (18). Although an early attempt to detect phosphorylation on class II MHC peptides met with failure (5), new technology has now made it possible to observe this modification as well (19). Here, we demonstrate the existence of MHC II-associated phosphopeptides on human melanoma cells and EBV-transformed B (EBV-B) lymphoblasts, and we define and compare the sequences of phosphopeptides complexed to HLA-DR molecules on 2 autologous pairs of melanoma and B cell cultures. Furthermore, we provide a previously undescribed demonstration of the ability of human CD4+ T cells to specifically recognize phosphoepitopes displayed in the context of MHC II molecules by using the example of an HLA-DRβ1*0101-restricted phospho-melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1 (phospho-MART-1) peptide isolated independently from 2 melanoma cell lines. These findings suggest that tumor-associated phosphopeptides provide targets for CD4+ as well as CD8+ T cells, potentially enabling the development of new immunotherapeutic strategies.

Results and Discussion

T Cell Recognition of the Candidate Phosphopeptide B-Raf mutpT599.

To assess the potential for human CD4+ T cells to specifically discriminate phosphoresidues, we first explored the candidate mutant melanoma antigen B-RafV600E (B-Raf mut), which is shared by 60% of melanomas (20). The somatic V600E mutation constitutively activates the B-Raf serine-threonine kinase, and hence the MAPK cascade, presumably by mimicking a phosphorylation event. V600E is juxtaposed to the known dominant phosphosite T599. We reported previously that in vitro stimulation of melanoma patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with a nonphosphorylated, 29-mer candidate B-Raf mut peptide generated B-Raf mut-specific HLA-DRβ1*0404-restricted CD4+ T cells that did not cross-react with the wild-type peptide (B-Raf wt) and that specifically recognized HLA-compatible melanoma cells expressing B-Raf mut (21). To investigate the fine specificity of MHC II-restricted CD4+ T cells for phosphate moieties, T cells raised against nonphosphorylated B-Raf mut were assessed for recognition of synthetic B-Raf mutpT599. These T cells failed to react to the phosphorylated peptide. Conversely, we used the monophosphorylated peptide B-Raf mutpT599 to sensitize new CD4+ T cell cultures, which specifically recognized both B-Raf mutpT599 and B-Raf wtpT599 but not their nonphosphorylated counterparts (Fig. S1). By using anti-MHC blocking antibodies and HLA-matched or mismatched allogeneic antigen-presenting cells (APCs), we characterized HLA-DR11 as the restricting MHC allele for T cell recognition of the B-Raf phosphopeptides. T cells sensitized in vitro against synthetic B-Raf mutpT599 failed to recognize melanoma cells, suggesting that the hypothetical epitope might not be generated by intracellular processing, or that the conformation of the exogenously pulsed peptide–MHC complex failed to reproduce the conformation of a naturally processed epitope (22). Importantly, however, these experiments provide a previously undescribed demonstration that, similarly to MHC I-restricted CD8+ T cells, human CD4+ T cells are capable of specifically recognizing phosphopeptides complexed to MHC II molecules, and that the phosphoresidue can be a critical determinant of recognition.

Identification and Characterization of HLA-DR-Associated Phosphopeptides.

To identify naturally processed tumor-associated, MHC II-restricted phosphopeptides as potential targets for immune recognition, we affinity-isolated HLA-DR peptide complexes from 2 cultured melanoma lines (1363-mel and 2048-mel) and their autologous EBV-B cell counterparts (1363-EBV and 2048-EBV). These cell lines were selected because they constitutively express significant levels of common HLA-DR molecules, as assessed by flow cytometric analysis using the pan-DR mAb L243 (Fig. S2) and HLA allele-specific mAbs. By HLA genotyping, 2048-mel and 2048-EBV contain HLA-DRβ1*0101, which is found in 31% of melanoma patients (23); DRβ1*0404, found in 6.5% of patients (23); and DRβ4*0103. Notably, 1363-mel and 1363-EBV contain a single DR molecule, HLA-DRβ1*0101, affording an opportunity to isolate phosphopeptides with unambiguous HLA allele restriction. Patients 2048 and 1363 share HLA-DRβ1*0101, enabling the possibility of finding commonly expressed peptides on cell lines from both patients.

A total of 175 phosphopeptides were sequenced from the 4 cell lines (Table 1, Table S1, and Table S2). Of note, this analysis does not account for peptides containing mutations, which would not be detected by existing search algorithms (see Materials and Methods). Twenty-three phosphopeptides were isolated from 2 or more cell lines, yielding a total of 150 unique phosphopeptides. Similar to nonphosphorylated MHC II-associated epitopes, the average length of the phosphorylated peptides was 16 aa (range, 8–28 aa) (24). Also characteristic of MHC II epitopes, 78% (117 of 150 sequences) were found within nested sets, defined as groups of peptides sharing core sequences but having distinct N and C termini. Most phosphopeptides were specifically expressed by either melanomas (Table 1) or EBV-B cells (Table S1), although some were expressed by both cell types (Table S2). Only 23 phosphopeptide sequences from 7 source proteins were identified from 1363-mel, whereas a larger number of phosphopeptide sequences (n = 65) and source proteins (n = 28) were identified from 2048-mel cells. The smaller number of sequences isolated from 1363-mel likely reflects the significantly lower expression of HLA-DR molecules by these cells, as well as their expression of a single DR allele (Fig. S2). Thirty-nine phosphopeptide sequences from 15 proteins, and 48 phosphopeptides from 20 proteins, were identified from 1363-EBV and 2048-EBV B cells, respectively. As might be anticipated because patients 1363 and 2048 share the HLA-DRβ1*0101 allele, phosphopeptides common to both patients occurred, including those found in both melanomas (MART-1 and tensin-3; Table 1) or in both EBV-B cell lines (CD20; Table S1). Experiments are in progress with melanomas and EBV-B cells generated from other patients to better define cell type-specific phosphatome “fingerprints” and potential immunotherapeutic targets specific for melanomas or EBV-associated malignancies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HLA-DR-associated phosphopeptides selectively expressed by melanoma cells

| Source protein | Location* | Phosphopeptide† | 1363-mel | 2048-mel | Known phosphosite (score)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1363-mel and 2048-mel | |||||

| Melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1/MART-1 | PM | 100APPAYEKLpSAEQ111 | + | − | N (0.988) |

| 100APPAYEKLpSAEQSPP114 | + | − | |||

| 100APPAYEKLpSAEQSPPP115 | ++ | ++ | |||

| 100APPAYEKLpSAEQSPPPY116 | + | + | |||

| Tensin-3 | PM | 1433FVSKVMIGpSPKKV1445 | − | +,+§ | N (0.486) |

| 1434VSKVMIGpSPKKV1445 | ++,+§ | +++,++§ | |||

| 1437VMIGpSPKKV1445 | +,+§ | − | |||

| 1363-mel alone | |||||

| Matrix-remodeling-associated protein 7 | PM | 142KYpSPGKLRGN151 | + | − | N (0.967) |

| 2048-mel alone | |||||

| Amino-terminal enhancer of split | N¶ | 176SKEDKNGHDGDTHQEDDGEKpSD197 | − | ++ | N (0.312) |

| Ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein-54 | UK | 43GSALGGGGAGLSGRASGGAQpSPLRYLHV71 | − | + | Y (0.664) |

| 46LGGGGAGLSGRASGGAQpSPLRYLHV71 | − | + | |||

| 58SGGAQpSPLRYLHVL72 | − | + | |||

| Anoctamin-8 | PM | 638EEGpSPTMVEKGLEPGVFTL656 | − | + | N (0.182) |

| 639EGpSPTMVEKGLEPGVFTL656 | − | + | |||

| 640GpSPTMVEKGLEPGVFTL656 | − | + | |||

| AP-3 complex subunit-Δ-1 | GM | 779EEMPENALPpSDEDDKDPNDPYRAL802 | − | + | Y (0.997) |

| Casein kinase II subunit-β | ER/G | 202QAASNFKpSPVKTIR215 | − | + | Y (0.788) |

| 203AASNFKpSPVKTIR215 | − | + | |||

| 205SNFKpSPVKTIR215 | − | + | |||

| 206NFKpSPVKTIR215 | − | + | |||

| 207FKpSPVKTIR215 | − | + | |||

| Claudin-11 | PM | 191YYTAGSSpSPTHAKSAHV207 | − | + | N (0.992) |

| 196SSpSPTHAKSAHV207 | − | + | |||

| Emerin | NM | 117VRQpSVTSFPDADAFHHQ133 | − | ++ | Y (0.989) |

| FLJ20689 | UK | 471FKMPQEKpSPGYS482 | − | ++ | N (0.786) |

| Insulin receptor substrate 2 | PM | 1097RVApSPTSGVKR1107 | − | + | Y (0.992) |

| Interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein | PM | 543QVAMPVKKSPRRSpSSDEQGLSYSSLKNV570 | − | ++ | N (0.998) |

| 544VAMPVKKSPRRSpSSDEQGLSYSSLKNV570 | − | + | |||

| LUC7-like isoform b | N | 353SSNGKMASRRpSEEKEAG369 | − | + | Y (0.997) |

| 353SSNGKMASRRpSEEKEAGEI371 | − | + | |||

| Membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 1 | MIM/ERM | 172KEGEEPTVYpSDEEEPKDESARKND195 | − | + | Y (0.990) |

| 173EGEEPTVYpSDEEEPKDESARKND195 | − | ++ | |||

| NF-κB inhibitor-interacting Ras-like protein 2 | C¶ | 165ASKMTQPQSKSAFPLSRKNKGpSGpSLDG191 | − | ++ | N (0.436/0.046) |

| Probable fibrosin-1 long-transcript protein isoform 2 | UK | 348APPPLVPAPRPSpSPPRGPGPARADR372 | − | ++ | N (0.997) |

| Small acidic protein | UK | 2SAARESHPHGVKRSApSPDDDLG23 | − | + | Y (0.998) |

| 2(AcS)AARESHPHGVKRSApSPDDDLG23 | − | +++ | |||

| Synaptojanin-170 | C | 1561ASKApSPTLDFTER1573 | − | + | Y (0.574) |

| Tetraspanin-10 | PM | 4GERpSPLLSQETAGQKP19 | − | + | N (0.129) |

| 4GERpSPLLSQETAGQKPL20 | − | ++ | |||

| 5ERpSPLLSQETAGQKP19 | − | ++ | |||

| 5ERpSPLLSQETAGQKPL20 | − | ++ | |||

| Transmembrane protein 184C | PM/C | 424TIGEKKEPpSDKSVDS438 | − | + | N (0.991) |

Protein sources were determined by searching peptide sequences against the nr and refseq databases for human proteins (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). −, not detected; +, <6 copies per cell; ++, 6–50 copies per cell; +++, 51–140 copies per cell; and nm, not measured.

*In the localization column: C, cytoplasm; E, endosome; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERM, endoplasmic reticulum membrane; G, Golgi; GM, Golgi membrane; LM, lysosome membrane; M, membrane; MIM, microsomal membrane; MTM, mitochondrial membrane; N, nucleus; NM, nuclear membrane; PM, plasma membrane; and UK, Unknown.

†pS, pT, and pY correspond to serine, threonine, or tyrosine-associated phosphorylated residues, respectively. Italics indicate the exact site of phosphorylation could not be determined.

‡Phosphosites searched in the Phospho-ELM database (41). Values in parentheses show the score from the NetPhos 2.0 Server (22) indicating the probability for the site to be phosphorylated, scale 0–1.0. Higher scores indicate greater confidence in the prediction, with the designated binding threshold at 0.500. In cases of undefined phosphorylation sites (italicized), both scores are given.

§Abundance of peptide containing Met and Metox, respectively.

¶Hypothetical localization.

Phosphosites were assigned unambiguously for 96% of the 175 phosphopeptides sequenced in this study. Phosphopeptides contained only 1 phosphorylated residue, with the exception of a phosphopeptide derived from frizzled 6 in 1363-mel, which contained 2 phosphoresidues (Table S2). Among a total of 57 defined phosphosites (accounting for redundancy in nested peptide sets), phosphate moieties were bound to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues in 93.0%, 5.3%, and 1.7% of cases, respectively. Interestingly, these frequencies are similar to those found in the HeLa cell-derived phosphoproteome (86.4%, 11.8%, and 1.8%, respectively; ref. 2), suggesting that there is no significant bias in the processing or MHC II binding of peptides containing a particular phosphoresidue. Of note, studies have not identified MHC I-associated phosphopeptides containing phosphotyrosine residues; this may be explained by the generally low frequency of this posttranslational modification, as well as by the relatively small number of phosphopeptides isolated in our earlier study compared with the current report (36 vs. 175 phosphopeptides, respectively; ref. 6). A total of 60% (32 of 53) of the source proteins for the phosphopeptides described in this report are known to be phosphorylated (Table S3). However, only 17 (29.8%) of the 57 defined phosphosites had been identified previously (Table 1, Table S1, and Table S2). When analyzed with an algorithm based on experimentally verified phosphorylation sites in eukaryotic proteins (NetPhos 2.0) (25), 80% (32 of 40) of the previously unknown phosphosites identified here are highly predicted to be true phosphorylation sites.

The 150 unique phosphopeptides listed in Table 1, Table S1, and Table S2 are derived from a total of 53 different protein sources representing all cellular compartments, although transmembrane proteins predominate, as would be expected for MHC II-associated peptides processed through the endosomal/lysosomal pathway. For those proteins located in the plasma membrane, the isolated phosphopeptides emanate from the cytoplasmic tail region. The processing of cytosolic and nuclear proteins via the MHC II pathway does not fit the “classical” model of antigen processing. However, mounting evidence suggests that autophagy, a stress-activated process operational in intracellular protein turnover, may play a critical role in shunting cytoplasmic proteins into the lysosomal compartment, thus influencing the MHC II–peptide repertoire (26, 27). Importantly, the majority of source proteins for the phosphopeptides found in this study are known to support vital biological functions, such as metabolism, cell cycle regulation, and intracellular signaling, and they may have important roles in cancer development, growth, and metastasis (Table S3). Thus, the derivative phosphopeptides may provide functionally relevant targets for immunotherapy.

Analyzing the abundance of the isolated phosphopeptides revealed ≤50 copies per cell, with rare exceptions (sequestosome-1 in 1363-mel, small acidic protein and tensin-3 in 2048-mel, and CD20 in 2048-EBV were present at 51–140 copies per cell). In fact, many phosphopeptides were found to be expressed at less than 6 copies per cell (Table 1, Table S1, and Table S2). This highlights the exquisite sensitivity of the mass spectrometric methods used for detection. Because T cell responses may be activated by fewer than 10 peptide–MHC complexes per cell, the phosphopeptides described in this report are potentially immunogenic (28–30).

Specific CD4+ T Cell Recognition of Phospho-MART-1.

To assess the ability of human CD4+ T cells to specifically recognize tumor-associated phosphopeptides, we selected the MART-1100–111 phosphopeptide (pMART-1, containing pS108) for further study. As shown in Table 1, a nested set of phosphopeptides derived from the C terminus of MART-1 was eluted from both 1363-mel and 2048-mel—which share HLA-DRβ1*0101—but not from the autologous EBV-B cell lines. Because of its selective expression pattern in cells of the melanocytic lineage, including normal melanocytes and melanoma cells, MART-1 (also termed Melan-A) is an important target of immunotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of melanoma, including vaccines and adoptive T cell transfer (31, 32). This transmembrane protein, which is localized to melanosomes and functions to regulate mammalian pigmentation (33), was not known to be phosphorylated before the current report. However, several nonphosphorylated MHC class I- and class II-restricted immunogenic epitopes have been identified in MART-1, spanning the entire protein (34–38). Some have provided the basis for synthetic melanoma peptide vaccines.

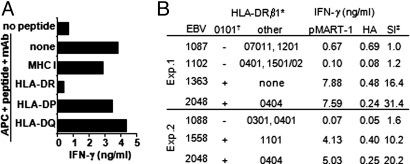

Fresh PBMCs from melanoma patient D7, with the MHC II genotype HLA-DRβ1*01, HLA-DQβ1*0501, were repeatedly stimulated in vitro with the pMART-1 peptide under microculture conditions. After several rounds of stimulation, the CD4+ microculture designated D7-pM specifically secreted IFN-γ (Fig. 1) and GM-CSF in response to the pMART-1 peptide, but not to the nonphosphorylated MART-1 peptide pulsed onto DR1-expressing APCs. In titration experiments, pMART-1 could be recognized at concentrations <1 μM. As shown in Fig. 1, the tensin-31434–1445 phosphopeptide (pTensin-3), also eluted from 1363-mel, was not recognized by D7-pM T cells, nor were other peptides having high affinity for HLA-DR1, including TPImut and HA. Conversely, CD4+ T cells specific for TPImut or HA secreted cytokines in response to their cognate epitopes but were not stimulated by pMART-1. These data suggest that CD4+ D7-pM T cells specifically recognize pMART-1 and that the phosphorylated serine residue is a critical determinant of recognition.

Fig. 1.

CD4+ T cells specifically recognize the melanoma-associated phosphopeptide pMART-1. Peptide recognition by D7-pM T cells raised against pMART-1 (Top) is compared to recognition by CD4+ HA-specific cells from the same patient (Middle) or by TPImut-specific CD4+ TIL1558 (Bottom). Peptides were pulsed onto HLA-DR1+ 2048-EBV cells. Similar results were obtained by using DR1+ 1363-EBV as APC.

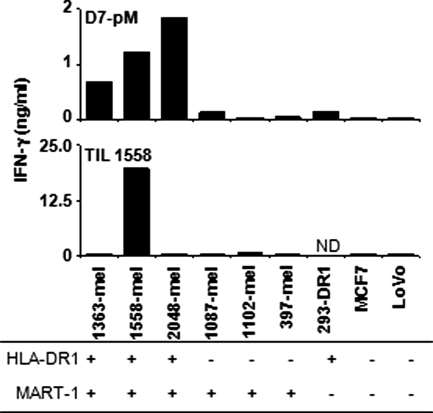

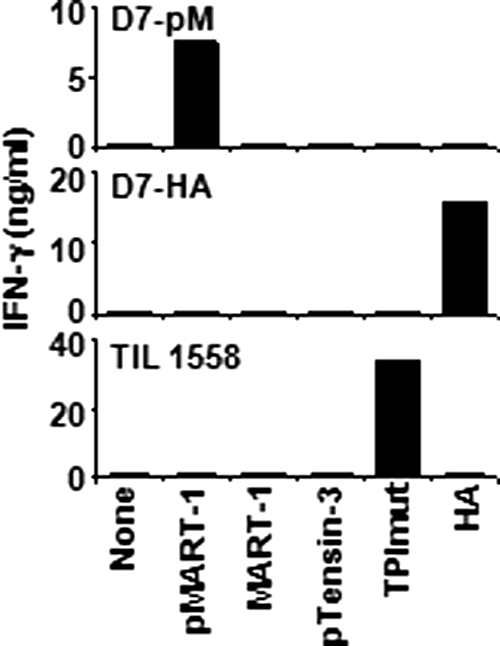

A nested set of 4 MART-1 phosphopeptides was eluted from 1363-mel and 2048-mel, sharing HLA-DRβ1*0101 (Table 1). Because phosphopeptides complexed to MHC molecules were affinity-eluted on an anti-HLA-DR column, and because HLA-DRβ1*0101 is the only DR molecule contained in 1363-mel by genotyping, we hypothesized that HLA-DRβ1*0101 was the restriction element for pMART-1 recognition by CD4+ D7-pM T cells. This was investigated with 2 complementary approaches: anti-MHC mAbs were used to inhibit T cell recognition of peptide-pulsed APCs, and a panel of allogeneic APCs with diverse HLA types was used to present pMART-1 to T cells (Fig. 2). T cell recognition of DR1+ 2048-EBV pulsed with pMART-1 was significantly inhibited by an mAb directed against HLA-DR (L243) but not by mAbs against HLA-DQ, HLA-DP, or class I MHC (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, D7-pM T cells specifically recognized the pMART-1 peptide only when pulsed onto allogeneic EBV-B cells sharing HLA-DRβ1*0101 (Fig. 2B). Next, we sought to determine whether D7-pM T cells could also recognize whole melanoma cells expressing MART-1 and HLA-DRβ1*0101. As shown in Fig. 3, D7-pM T cells recognized all of the 3 allogeneic melanomas tested that expressed both HLA-DRβ1*0101 and MART-1, but they failed to recognize DR1-negative or MART-1-negative cells. In the same experiment, DR1-restricted CD4+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) 1558, specific for the TPImut antigen unique to 1558-mel, recognized 1558-mel but not the other tumors (39). Two repeat experiments yielded similar results. HLA-DR restriction of tumor recognition by T cells was confirmed with anti-MHC mAb blockade. Of interest, although D7-pM CD4+ T cells specifically reacted against intact DR1+ MART-1+ tumor cells, they failed to recognize DR1+ EBV-B cells pulsed with lysates of MART-1+ tumors. In the same experiment, CD4+ TIL 1558 recognized processed 1558-mel lysate and provided a positive control for exogenous pathway processing (39). Thus, although MART-1 is a transmembrane protein, the pMART-1 epitope did not appear to be processed through the exogenous/endosomal route in these preliminary experiments. Future work will address the mechanism by which pMART-1 is processed intracellularly for presentation in the context of MHC class II molecules.

Fig. 2.

HLA-DR1β1*0101 restriction of D7-pM CD4+ T cells specific for the pMART-1 peptide. (A) An anti-HLA-DR mAb inhibits T cell recognition of peptide-pulsed 2048-EBV. (B) T cells recognize pMART-1 peptide presented by allogeneic DR1+ APC. T cell IFN-γ secretion measured by ELISA. †, Genotype; EBV-B cell expression of HLA-DR1 was confirmed by flow cytometry. ‡, Stimulation index (SI), ratio of IFN-γ secretion in response to pMART-1 versus the irrelevant HA peptide. SI >2 is considered significant.

Fig. 3.

D7-pM T cells specific for pMART-1 peptide recognize allogeneic intact melanoma cells expressing MART-1 and HLA-DRβ1*0101. In comparison, DR1-restricted CD4+ TIL 1558 cells are specific for autologous melanoma cells expressing the unique tumor antigen TPImut (39). HLA-DR1 expression was determined by flow cytometry. MART-1 expression was determined by recognition from HLA-A2-restricted MART-1 T cell receptor-transduced T cells, intracellular staining with a MART-specific mAb (42), and/or Northern blotting (32). ND, not done.

In summary, our demonstration of phosphopeptides associated with human MHC II molecules has revealed a new cohort of tumor antigens potentially recognizable by the immune system and therefore targetable by cancer immunotherapies. Although tumor-associated, MHC class II-restricted phosphopeptides were previously thought to be degraded within the MHC II processing environment, recent technological advances have enabled us to identify a large number of phosphoepitopes from both melanoma and EBV-B cell lines. These may provide optimal targets for immunotherapy because intracellular phosphoproteins associated with dysregulated signaling pathways play an important role in supporting the malignant cell phenotype and in providing escape mechanisms from antineoplastic agents. MART-1, a commonly expressed melanoma antigen containing MHC I- and MHC II-restricted epitopes, has been a focus of cancer immunotherapeutics for more than a decade and has now been revealed as a phosphoprotein recognizable by phosphopeptide-specific CD4+ T cells derived from a melanoma patient. Similarly, 2 phosphoproteins shown here to be sources for MHC II-restricted peptides—tensin-3 and insulin receptor substrate 2—have been shown previously to generate MHC I-restricted phosphopeptides (6). These findings suggest opportunities for developing combinatorial treatment approaches using both MHC I- and MHC II-restricted phosphopeptides as immunogens for raising potent, polyvalent tumor-specific immunity.

Materials and Methods

Cultured Cell Lines.

Details on cell lines used in these experiments are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Human tissues were obtained through protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. HLA genotypes of patients and cultured cell lines were determined by the NIH Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center HLA Laboratory (Bethesda, MD) by using sequence-specific PCR techniques.

Isolation of HLA-DR-Associated Peptides.

To prepare cells for extraction of MHC–peptide complexes, growing cultures were harvested, and spent medium was removed by centrifugation. Cells were washed twice in cold PBS, and dry cell pellets were snap frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C for subsequent lysis. HLA-DR–peptide complexes were immunoaffinity-purified from melanoma and EBV-B cells, and the associated peptides were extracted according to methods for MHC I-associated peptides (6), with minor modifications (SI Materials and Methods).

Phosphopeptide Enrichment.

Immunoaffinity-purified peptides were converted to methyl esters as previously described (6) (SI Materials and Methods). A phosphopeptide standard, angiotensin II phosphate (100 fmol), was spiked into all samples before the esterification step to monitor the efficiency of the phosphopeptide enrichment.

Phosphopeptide Sequence Analysis by Tandem Mass Spectrometry.

Phosphopeptides were analyzed by nanoflow HPLC-microelectrospray ionization coupled to either a hybrid linear quadrupole ion trap-Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance (LTQ-FT) mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or an LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) modified to perform electron transfer dissociation (ETD). A precolumn loaded with phosphopeptides was connected with polytetrafluoroethylene tubing (0.06-inch o.d. and 0.012-inch i.d.; Zeus Industrial Products) to the end of an analytical HPLC column (360-μm o.d. and 50 μm i.d.) containing 7 cm of C18 reverse-phase packing material (5-μm particles; YMC). Phosphopeptides were eluted to the mass spectrometer at a flow rate of 60 nL/min with a gradient: A = 0.1 M acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) in H2O; B = 70% acetonitrile (Malinckrodt) and 0.1 M acetic acid in H2O; 0–60% B in 20 min, 60–100% B in 5 min. Parameters used to acquire ETD/MS/MS spectra in a data-dependent mode on the modified LTQ instrument have been described previously (40).

Data Analysis.

ETD and collision activated dissociation (CAD) MS/MS spectra of class II phosphopeptides were interpreted manually by J.S. and D.F.H. Data for the 175 sequences reported here were unambiguous. None of the sequences were assigned by software. Approximate copy/cell numbers for each phosphopeptide were determined by comparing peak areas of the observed parent ions to that of angiotensin II phosphate (DRV[pY]IHPF, 100 fmol; Calbiochem) spiked into the sample mixture before peptide esterification and immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Specific functional and intracellular localization information for source proteins was determined from the Uniprot database (www.uniprot.org). Source proteins for the identified phosphopeptides were searched in the Phospho-ELM database (http://phospho.elm.eu.org) (41) to determine whether the phosphoresidue was previously described or novel. Phosphopeptide sequences were analyzed in the NetPhos 2.0 Server (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos) (25), to obtain a prediction score indicating the confidence in occurrence of the phosphorylation site.

Peptides.

Synthetic peptides used in this study are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Generation of Human Phosphopeptide-Specific CD4+ T cells.

Peptide-specific CD4+ T cells were raised by repetitive in vitro stimulation of PBMCs from melanoma patients, as described previously (21). For candidate B-Raf phosphopeptides, patients were selected whose melanomas harbored the common T1799A (V600E) mutation. For pMART-1, selected patients expressed the HLA-DRβ1*0101 allele. Briefly, PBMCs were cultured in flat-bottom 96-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well in RPMI 1640 plus 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum. GM-CSF (200 units/mL) and IL-4 (100 units/mL; PeproTech) were added on day 0 to generate dendritic cells as APCs, along with 25 μM peptide. Recombinant IL-2 (120 IU/mL) was added to lymphocyte cultures on day 7 and replenished every 4–7 days. For pMART-1 experiments, IL-7 and IL-15 were also added at 25 ng/mL at day 7 and were replenished every 4–7 days. Thereafter, T cells were restimulated every 10–14 days with irradiated autologous PBMCs or EBV-B cells pulsed with phosphopeptide, 1 × 105 feeder cells per well. Long-term CD4+ T cell cultures were maintained in 120 IU/mL IL-2 and 20% conditioned medium from lymphokine-activated killer cell cultures (B-Raf-specific T cells) or 120 IU/mL IL-2, 25 ng/mL IL-7, and 25 ng/mL IL-15 (pMART-1-specific T cells). CD4+ TIL from melanoma patient number 1558, recognizing a unique HLA-DR1-restricted mutant TPI epitope, were used as controls in some experiments (39).

T Cell Recognition Assays.

To assess specific peptide recognition, 0.2 × 105 to 1.0 × 105 T cells per well were cocultured overnight in flat-bottom 96-well plates with 1 × 105 EBV-B cells that had been prepulsed for 16–24 h with peptides at 20 μM (pB-Raf experiments) or 25 μM (pMART-1 experiments). Culture supernatants were then harvested, and GM-CSF or IFN-γ secretion by activated T cells was measured by using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems). When allogeneic EBV-B cells were used as APCs to determine the MHC restriction of peptide-specific T cells, excess peptide was washed off before combining APCs with T cells. Intact tumor cell recognition was tested by incubating T cells (5 × 104 per well) in microtiter plates with melanoma cells (1 × 105 per well) for 20 h. In some assays, mAbs directed against MHC molecules were used to inhibit T cell reactivity, including W6/32 (IgG2a, anti-MHC class I; American Type Culture Collection), L243 (IgG2a, anti-HLA-DR; American Type Culture Collection), B7/21 (IgG1, anti-HLA-DP; Becton Dickinson), and SPVL3 (IgG2a, anti-HLA-DQ; Beckman Coulter). Final concentrations of mAb in blocking assays were 2.5 μg/mL for B7/21 and 20 μg/mL for the others. Surface expression of HLA-DR1 on tumor and EBV-B cells was confirmed by flow cytometry after staining with biotinylated anti-DR1, 10, 103 (One Lambda) and counterstaining with streptavidin-phycoerythrin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Drew Pardoll for his critical review of the manuscript. This work was funded by the Departments of Surgery and Oncology at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (F.R.D., T.L.M., T.M.S., and S.L.T.), a grant from the Melanoma Research Alliance (to V.H.E., D.F.H., and S.L.T.), and U.S. Public Health Service Grants AI33993 (to D.F.H.) and AI20963 (to V.H.E.).

Note Added in Proof.

We have recently become aware of work by Meyer VS et al. (43) identifying MHC II-associated phosphopeptides from a human melanoma line and a B lymphoblastoid line.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903852106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Guinn BA, et al. Recent advances and current challenges in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen JV, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haluska FG, et al. Genetic alterations in signaling pathways in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2301s–2307s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oka M, Kikkawa U. Protein kinase C in melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-1578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarling AL, et al. Phosphorylated peptides are naturally processed and presented by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1755–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarling AL, et al. Identification of class I MHC-associated phosphopeptides as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen MH, et al. Phosphorylated peptides can be transported by TAP molecules, presented by class I MHC molecules, and recognized by phosphopeptide-specific CTL. J Immunol. 1999;163:3812–3818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogan KT, et al. The peptide recognized by HLA-A68.2-restricted, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is derived from a mutated elongation factor 2 gene. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5144–5150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson JK, Otvos L, Jr, Ertl HC. Posttranslational side chain modification of a viral epitope results in diminished recognition by specific T cells. J Virol. 1992;66:3996–4002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.3996-4002.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monneaux F, Lozano JM, Patarroyo ME, Briand JP, Muller S. T cell recognition and therapeutic effect of a phosphorylated synthetic peptide of the 70K snRNP protein administered in MR/lpr mice. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:287–296. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otvos L, Jr, et al. The effects of post-translational side-chain modifications on the stimulatory activity, serum stability and conformation of synthetic peptides carrying T helper cell epitopes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1313:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(96)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Stipdonk MJ, et al. T cells discriminate between differentially phosphorylated forms of alphaB-crystallin, a major central nervous system myelin antigen. Int Immunol. 1998;10:943–950. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yadav R, et al. The H4b minor histocompatibility antigen is caused by a combination of genetically determined and posttranslational modifications. J Immunol. 2003;170:5133–5142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohammed F, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between antigenic peptides and MHC class I: A molecular basis for the presentation of transformed self. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1236–1243. doi: 10.1038/ni.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen J, et al. Phosphorylated self-peptides alter human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted antigen presentation and generate tumor-specific epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2776–2781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812901106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerloni M, Zanetti M. CD4 T cells in tumor immunity. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;27:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pardoll DM, Topalian SL. The role of CD4+ T cell responses in antitumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:588–594. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelhard VH, Altrich-Vanlith M, Ostankovitch M, Zarling AL. Post-translational modifications of naturally processed MHC-binding epitopes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Depontieu F, et al. Tumor-associated MHC II-restricted phosphopeptides: New targets for immune recognition. FASEB J. 2008;22:1079.1071. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies H, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharkey MS, Lizee G, Gonzales MI, Patel S, Topalian SL. CD4(+) T-cell recognition of mutated B-RAF in melanoma patients harboring the V599E mutation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1595–1599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viner NJ, Nelson CA, Deck B, Unanue ER. Complexes generated by the binding of free peptides to class II MHC molecules are antigenically diverse compared with those generated by intracellular processing. J Immunol. 1996;156:2365–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marincola F, Stroncek D, Simonis T. In: HLA 1998. Gjertson DW, Terasaki PI, editors. Lenexa, KS: American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics; 1998. pp. 276–277. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lippolis JD, et al. Analysis of MHC class II antigen processing by quantitation of peptides that constitute nested sets. J Immunol. 2002;169:5089–5097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1351–1362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nimmerjahn F, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted presentation of a cytosolic antigen by autophagy. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1250–1259. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dengjel J, et al. Autophagy promotes MHC class II presentation of peptides from intracellular source proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501190102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kageyama S, Tsomides TJ, Sykulev Y, Eisen HN. Variations in the number of peptide-MHC class I complexes required to activate cytotoxic T cell responses. J Immunol. 1995;154:567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irvine DJ, Purbhoo MA, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature. 2002;419:845–849. doi: 10.1038/nature01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engelhard VH, Brickner AG, Zarling AL. Insights into antigen processing gained by direct analysis of the naturally processed class I MHC associated peptide repertoire. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coulie PG, et al. A new gene coding for a differentiation antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J Exp Med. 1994;180:35–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawakami Y, et al. Cloning of the gene coding for a shared human melanoma antigen recognized by autologous T cells infiltrating into tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3515–3519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoashi T, et al. MART-1 is required for the function of the melanosomal matrix protein PMEL17/GP100 and the maturation of melanosomes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14006–14016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bioley G, et al. Melan-A/MART-1-specific CD4 T cells in melanoma patients: Identification of new epitopes and ex vivo visualization of specific T cells by MHC class II tetramers. J Immunol. 2006;177:6769–6779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godefroy E, et al. Identification of two Melan-A CD4+ T cell epitopes presented by frequently expressed MHC class II alleles. Clin Immunol. 2006;121:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larrieu P, Ouisse LH, Guilloux Y, Jotereau F, Fonteneau JF. A HLA-DQ5 restricted Melan-A/MART-1 epitope presented by melanoma tumor cells to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1565–1575. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0300-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marincola FM, Rivoltini L, Salgaller ML, Player M, Rosenberg SA. Differential anti-MART-1/MelanA CTL activity in peripheral blood of HLA-A2 melanoma patients in comparison to healthy donors: Evidence of in vivo priming by tumor cells. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:266–277. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zarour HM, et al. Melan-A/MART-1(51–73) represents an immunogenic HLA-DR4-restricted epitope recognized by melanoma-reactive CD4(+) T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:400–405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pieper R, et al. Biochemical identification of a mutated human melanoma antigen recognized by CD4(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:757–766. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chi A, et al. Analysis of phosphorylation sites on proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diella F, Gould CM, Chica C, Via A, Gibson TJ. Phospho.ELM: A database of phosphorylation sites–update 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D240–D244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawakami Y, et al. Production of recombinant MART-1 proteins and specific antiMART-1 polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies: Use in the characterization of the human melanoma antigen MART-1. J Immunol Methods. 1997;202:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer VS, et al. Identification of natural MHC class II presented phosphopeptides and tumor-derived MHC class I phospholigands. J Proteome Res. 2009 May 5; doi: 10.1021/pr800937k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.