To those of us who grew up in the 1950s, life used to be simple. Weaned on Leave it to Beaver and Ozzie and Harriet, it seemed that everyone had a prespecified job: Dad went to the office, Mom baked cookies, and the kids went to school. Surprisingly, although most cell biologists view themselves as relatively enlightened, many still continue to view the role of the mitochondria within the framework of a very 1950s paradigm. Yes, it is argued, the mitochondria have a job to do in the cell, but that job merely involves generating the ATP required to power various complex cellular processes such as growth and differentiation. Thankfully, this antiquated notion of mitochondria is slowly giving way to a more nuanced, some would say modern, point of view. The latest impetus for this scientific update is provided by the work of Lippincott-Schwartz and her colleagues in this issue of PNAS (1). Their observations demonstrate a fascinating new role for the mitochondria in the G1–S transition. These results suggest that in the complicated and highly choreographed events surrounding cell-cycle progression mitochondria are not simple bystanders but instead full-fledged participants.

Previous analysis has demonstrated that mitochondria can arrange themselves into either long tubular and filamentous structures or a more discrete and fragmented pattern (2). Similarly, through the process of fusion and fission, mitochondria can rapidly interconvert between these two distinct morphologies. Surprisingly, relatively little was known regarding the relationship between mitochondria morphology and cell-cycle progression. In this new study (1), careful image analysis has revealed that although growing cells appear to have a mixture of tubular and fragmented mitochondria, cells at the G1–S border form a single, giant tubular network. This network appears to be unique, forming only at the G1–S transition and is characterized by a syncytia of mitochondria that are both electrically coupled and unusually hyperpolarized (Fig. 1). These unusual electrical characteristics might relate to previous observations that described a peculiar increase in mitochondrial oxygen consumption during the G1–S transition (3). In an effort to understand how these mitochondrial events fit within the well-established paradigm of cell-cycle progression, Lippincott-Schwartz and colleagues (1) then went on to demonstrate that strategies that induce mitochondrial fusion can trigger expression of cyclin E. Indeed, for cells arrested in G0, hyperfusion of the mitochondria can in many ways mimic what normally occurs after growth factor or serum stimulation. For instance, for cells in G0, both mitochondrial fusion and serum addition appear to produce similar levels of S-phase progression as judged by BrdU incorporation. These results, coupled with additional experiments where the mitochondrial membrane potential was purposely reduced, suggest that the unique mitochondrial structure formed at the G1–S transition is required for the transition itself. Nonetheless, as mentioned above, this mitochondrial mesh is a transient phenomenon. Additional data from this study suggest that if the tubular network is purposely maintained beyond the G1–S boundary, cells are now unable to proceed with normal cell cycle progression. Furthermore by using isogenic cells lines, this subsequent cell-cycle arrest was shown to require the tumor suppressor p53.

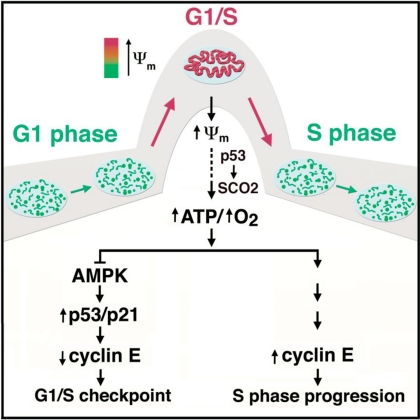

Fig. 1.

A putative model for the role of mitochondria in the G1–S transition. Throughout most of the cell cycle, mitochondria appear as a combination of either tubular or fragmented morphologies. Surprisingly, at the G1–S transition, the mitochondria coalesce into a giant, single tubular network. This network is electrically coupled and exhibits a hyperpolarized mitochondrial membrane potential (ψm). Because ψm is the ionic gradient used to generate ATP, it is not surprising that this unique morphological and bioenergetic mitochondrial network appears to allow for increased ATP generation. Based on ref. 1, and previous studies in mammalian cells and lower organisms, the absence of this energetic boost may trigger a G1–S checkpoint that involves the sequential activation of AMPK and p53 and ultimately the down-regulation of cyclin E levels. In addition, ref. 1 suggests that increased mitochondrial activity can positively regulate cyclin E levels and trigger S-phase progression. Note, in this putative model, p53 regulates events in several different contexts, including the transcriptional induction of p21, the cell cycle regulator, and SCO2, a factor that has been demonstrated to regulate mitochondrial oxygen consumption.

These newest observations need to be placed in context of a small, but growing, body of literature demonstrating a connection between intracellular energetics and cell-cycle progression. Given the significant energy requirement needed to synthesize all of the lipid, protein, and nucleic acid required for cell division, it would seem prudent that some coordination existed between the consumer and supplier of ATP. Yet how the mitochondria is integrated into these complex events has until recently been largely ignored. Perhaps one of the earliest clues came from analysis of an imaginal disc eye mutant in Drosophila (4). This particular mutant encoded an essential component of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal respiratory complex in mitochondrial electron transport. Flies carrying this cytochrome c oxidase mutation have white, glossy-appearing eyes, as opposed to the usual red, faceted structure. Subsequent analysis using in vivo BrdU incorporation and analysis of cell-cycle regulatory proteins demonstrated that this particular mitochondrial mutant did not alter cell viability or differentiation capacity, but instead led to a specific G1 arrest. Additional biochemical analysis revealed that in these mutant flies impaired mitochondrial function led to a reduction in ATP, which in turn, triggered the activation of AMP-activated kinase (AMPK). The activation of AMPK was then shown to augment p53 activity, a decrease in cyclin E levels, and enforcement of a G1–S block. Surprisingly, mutants of AMPK or p53 could bypass the G1–S block and rescue the observed abnormal eye formation without actually improving the underlying energetic defect. This finding led Mandal et al. (4) to conclude that a “mitochondrial checkpoint” existed in late G1, where low ATP triggers the activation of an AMPK–p53–cyclin E-dependent pathway that presumably arrests energetically impaired cells, stopping them from making the presumably overtaxing commitment to cell division.

Although the results in Drosophila provided a nice in vivo demonstration of a possible mitochondrial-regulated checkpoint, parallel studies in mammalian cells have further demonstrated the growing connection between energetics and cell-cycle progression. For instance, in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), withdrawal of glucose has also been shown to lead to an AMPK- and p53-dependent activation of a G1–S checkpoint (5). Activation of AMPK after energetic stress can also lead to phosphorylation of the mTOR binding partner raptor (6). These events lead to an inhibition of mTOR activity, which also regulates the G1–S transition and represents another potentially distinct energetic checkpoint. This growing complexity is also underscored by investigations in Drosophila that has demonstrated that, in addition to the pathways described above, mitochondrial dysfunction can induce a G1–S arrest by alternative means (7). Indeed, a mutant in complex I of the electron transport has been recently shown to induce cell-cycle arrest through a pathway involving mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, followed by activation of the fly homologs of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), the FOXO transcription factor, and the cell-cycle regulator p27.

At the G1–S transition, the mitochondria coalesce into a giant, single tubular network.

All of these studies suggest that mitochondrial function and energetic status are much more intimately connected to the cell cycle than originally believed. Nonetheless, numerous questions remain. For instance, in ref. 1, how exactly are the fusion events leading to the giant tubular network observed at the G1–S transition achieved? Is the activity of the fusion/fission machinery under direct control of cell-cycle-regulated kinases? Do the intriguing results suggesting that mitochondrial hyperfusion can trigger S-phase entry suggest that growth factor signaling might normally function as a direct regulator of mitochondrial structure? From a purely energetic point of view, how does the giant tubular network achieve such a hyperpolarized state? Indeed, although there is growing evidence that mitochondrial membrane potential correlates and potentially regulates important biological outcomes (8), virtually nothing is known regarding how dynamic regulation of mitochondrial membrane potential is achieved.

Finally, what do these results tell us about conditions where cellular energetics and cell-cycle checkpoints are both impaired? It is tempting to speculate that the well-characterized alterations in tumor cell metabolism such as the Warburg effect, in which mitochondrial respiration is depressed and aerobic glycolysis is augmented, somehow relate to these new findings. Indeed, one pathway through which p53 can directly regulate mitochondrial oxygen consumption is by transactivation of SCO2, an assembly factor for cytochrome c oxidase (9). Similarly, other tumor suppressors and oncogenes such as c-myc can also regulate key components of mitochondrial function such as cytochrome c (10). Such regulation may suggest that the handful of genes commonly altered or deleted in human tumors might ultimately provide the genetic link between mitochondria function and cell-cycle checkpoints. Furthermore, while the study in ref. 1 was performed within the context of immortalized cells, it remains unclear how the giant tubular network of mitochondria observed at the G1–S border might differ morphologically or functionally in normal versus transformed cells. A previous study (11), using less precise tools, hinted that a similar mitochondrial network might also occur in yeast, suggesting that the transient mitochondrial syncytia may in fact be evolutionary conserved. Undoubtedly, because of the work of Lippincott-Schwartz and colleagues (1), the connection between the mitochondria and the cell cycle, long ignored and overlooked, will now receive considerably more attention. Perhaps with this attention, the notion that the mitochondria are semiautonomous organelles that merely provide ATP will, like poodle skirts and hula hoops, finally fade away. Progress indeed, now if we could only get rid of those reruns of Leave It to Beaver.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 11960.

References

- 1.Mitra K, Wunder C, Roysam B, Lin G, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A hyperfused mitochondrial state achieved at G1–S regulates cyclin E buildup and entry into S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11960–11965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detmer SA, Chan DC. Functions and dysfunctions of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nrm2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schieke SM, McCoy JP, Jr, Finkel T. Coordination of mitochondrial bioenergetics with G1-phase cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1782–1787. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.12.6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandal S, Guptan P, Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. Mitochondrial regulation of cell cycle progression during development as revealed by the tenured mutation in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2005;9:843–854. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RG, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2005;18:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gwinn DM, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owusu-Ansah E, Yavari A, Mandal S, Banerjee U. Distinct mitochondrial retrograde signals control the G1–S cell cycle checkpoint. Nat Genet. 2008;40:356–361. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schieke SM, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism modulates differentiation and teratoma formation capacity in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28506–28512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802763200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matoba S, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrish F, Giedt C, Hockenbery D. c-MYC apoptotic function is mediated by NRF-1 target genes. Genes Dev. 2003;17:240–255. doi: 10.1101/gad.1032503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyakawa I, Aoi H, Sando N, Kuroiwa T. Fluorescence microscopic studies of mitochondrial nucleoids during meiosis and sporulation in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 1984;66:21–38. doi: 10.1242/jcs.66.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]