Abstract

In this paper, we describe a rapid flow cytometry method to identify antimicrobial peptides that are internalized into bacterial cells and differentiate them from those that are membrane active. The method was applied to fluorescently labeled Bac71-35 and polymyxin B, whose mechanisms of action are, respectively, based on cell penetration and on membrane binding and permeabilization. Identification of peptides with the former mechanism is of considerable interest for the intracellular delivery of membrane-impermeant drugs.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are effectors of innate immunity that have evolved different mechanisms to inactivate bacteria (3, 25). Most of them display amphipathic scaffolds that allow interaction with, and damage of membranes (6); others, such as the proline-rich peptides, kill bacteria without lytic effects and through interaction with intracellular targets (15, 16, 22). This mode of action implies that nonlytic AMPs have the capacity to be internalized by cells and are therefore cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs).

Although a vast literature has been produced on CPP entry of and localization in eukaryotic cells (9, 12, 14), little direct evidence of nonlytic peptide internalization into bacteria has been produced so far. The study of localization of AMPs in bacteria has relied on immunoelectron microscopy (16), which is incompatible with high-throughput screening, and on fluorescence confocal microscopy (13, 17), which is not quantitative.

To provide an effective tool to assay the internalization of CPPs in bacteria, here we propose a flow cytometric approach based on fluorescently labeled peptides and the use of the cell-impermeant quencher trypan blue (TB). To this aim, we investigated in parallel the internalization of Bac71-35, a nonlytic proline-rich peptide that penetrates gram-negative bacteria without membrane disruption (4, 7), and of polymyxin B (PMB), a cyclic peptide antibiotic that binds to the bacterial surface, causing membrane permeabilization (5, 18).

An N-terminal active fragment of Bac7, Bac71-35, was synthesized by linking the dipyrrometheneboron difluoride (BODIPY) fluorophor to a C-terminal cysteine residue (19), while BODIPY-labeled polymyxin B (PMB-BY) was purchased from Invitrogen. This probe was chosen since it leaves unchanged the net charge of the conjugated molecule, a crucial feature for the antimicrobial properties of the peptides. In addition, it is insensitive to pH and polarity (2), so that its spectral features are not influenced by the environment. The antibacterial activity of Bac71-35-BY and PMB-BY was determined on Escherichia coli HB101 and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 (1). The addition of BODIPY to Bac71-35 did not change its potency, with MICs of 0.5 to 1 μM for both of the bacterial strains. Conversely, the presence of BODIPY caused a fourfold MIC reduction (1 versus 0.25 μM) in the activity of PMB, an effect likely due to the higher BODIPY/PMB size ratio.

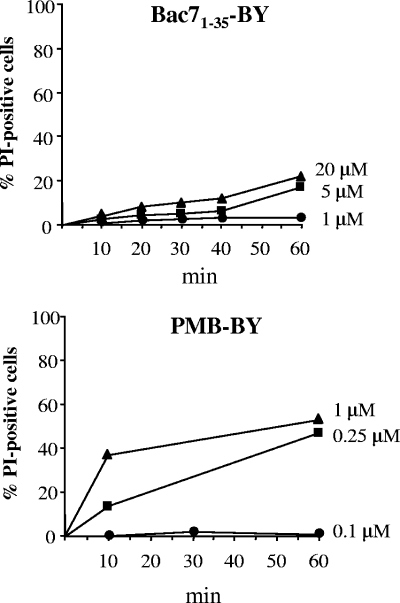

We initially checked the effect of the peptides on membrane permeabilization by measuring the percentage of propidium iodide (PI)-positive cells by flow cytometry as previously reported (16). Loss of membrane integrity, in fact, would allow TB to enter bacterial cells, thereby biasing the results. Based on these assays (Fig. 1), Bac71-35-BY and PMB-BY were used at nonpermeabilizing concentrations of, respectively, 0.25 and 0.1 μM.

FIG. 1.

Flow cytometric evaluation of membrane integrity after treatment with Bac71-35-BY and PMB-BY. Percentage of PI-positive cells after incubation of E. coli HB101 (1 × 106 CFU/ml) with 1, 5, or 20 μM Bac71-35-BY or 0.1, 0.25, or 1 μM PMB-BY is shown. The background level of permeabilized cells, obtained by using non-peptide-treated samples, was always lower than 3% and was subtracted from the corresponding peptide-treated sample.

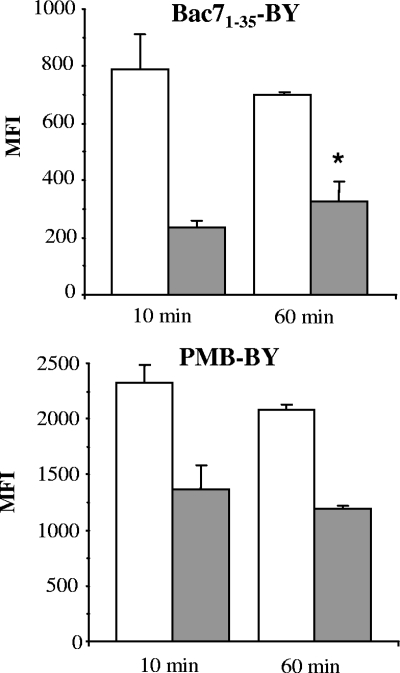

E. coli cells were then incubated for 10 min with Bac71-35-BY or PMB-BY and analyzed by flow cytometry. Both peptides bound efficiently to the cells (Fig. 2), in agreement with previous results for obtained with Bac71-35 (8) and PMB (20, 21). When the cells were washed with high-salt solution, to ensure that only peptide molecules strongly associated with the surface and/or internalized by cells were left, the cell-associated fluorescence decreased significantly. When the incubation time was extended to 60 min, the amount of Bac71-35-BY strongly associated with the cells increased significantly, while that of PMB-BY remained unchanged or slightly decreased, indicating faster binding kinetics and rapid saturation of binding sites by the latter peptide (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Binding of Bac71-35-BY and PMB-BY to E. coli HB101. Bacterial cells (1 × 106 CFU/ml) were incubated with 0.25 μM Bac71-35-BY or 0.1 μM PMB-BY for 10 or 60 min and then analyzed by flow cytometry without washing (empty histograms) or after washing with high-salt solution (gray filled histograms). Analyses were performed by using a Cytomics FC 500 (Beckman-Coulter, Inc.) equipped with an argon laser (488 nm, 5 mW) and detectors for filtered light set at 525 nm for BODIPY detection. Statistical analysis was performed by the unpaired t test. The average MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) ± standard deviation of four independent experiments is shown. *, P ≤ 0.05 for 60-min treatment versus 10-min treatment.

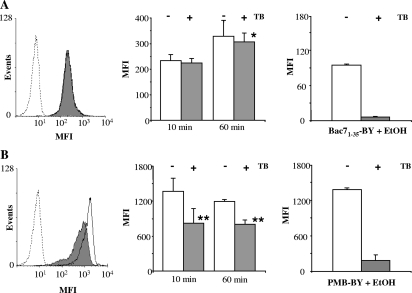

To analyze the peptides' penetration of bacterial cells, peptide-treated cells were incubated with TB, which is excluded from the interior of intact cells and which should quench only the extracellularly accessible BODIPY dye. TB has been used for many years for phagocytosis studies (10, 23) and in studies of CPP translocation into eukaryotic cells (11). However, to our knowledge, it was never used to investigate the uptake of peptides into bacterial cells. Peptide-treated HB101 cells were analyzed with a flow cytometer after addition of 1 mg/ml TB for 10 min at room temperature. The fluorescence intensity due to cell treatment with Bac71-35-BY for 10 min was not significantly reduced by the quencher (<5% reduction), while TB caused a highly significant reduction of fluorescence intensity (over 40%) in PMB-BY-treated cells (Fig. 3). Prolonging the incubation time to 60 min or increasing the peptide concentration (data not shown) caused a proportional increase in fluorescence intensity specifically for Bac71-35-BY while leaving the percentage of quenching unchanged. This effect was not observed with PMB-BY and is consistent with enhanced uptake of Bac71-35-BY within the cells. In addition, when E. coli cells were treated with Bac71-35-BY at 4°C, peptide fluorescence was not observed, indicating that membrane translocation was prevented (data not shown). Comparable results were obtained with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 (data not shown), indicating that this method may also be applied to gram-negative species other than E. coli.

FIG. 3.

Fluorescence quenching in E. coli cells exposed to Bac71-35-BY or PMB-BY. E. coli cells (1 × 106 CFU/ml) were incubated with 0.25 μM Bac71-35-BY (A) or 0.1 μM PMB-BY (B), washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry with (gray histograms) or without (empty histograms) incubation with TB for 10 min at 37°C. (Left panels) Representative experiments with E. coli cells treated for 10 min with the indicated peptide. Non-peptide-treated cells are shown by the dotted line. (Central panel) Fluorescence of cells treated with the peptides for 10 or 60 min. (Right panel) Fluorescence of cells treated with the peptides for 10 min and then permeabilized with ethanol (30 min at −20°C) before flow cytometry analysis. The average MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) ± standard deviation of four independent experiments is shown. *, P ≤ 0.05 for 60-min treatment versus 10-min treatment. **, P ≤ 0.01 for TB-treated cells versus non-TB-treated cells. EtOH, ethanol.

To exclude the possibility that the nonquenchable fluorescence fraction was due to factors other than peptide internalization, aliquots of bacterial cells were completely permeabilized with ethanol after incubation with the labeled peptides (24) and then incubated with TB. Alcohol treatment restored full accessibility to TB (Fig. 3, right panel), irrespective of the peptide used, indicating that the labeled peptides become fully accessible after ethanol treatment.

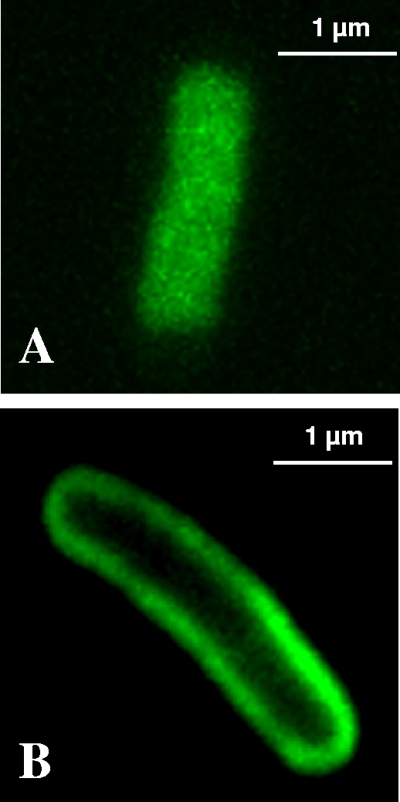

The cellular localization of Bac71-35-BY and PMB-BY in E. coli HB101 cells was confirmed by examining the cells in parallel by confocal scanning laser microscopy. Bac71-35-BY appeared to be homogeneously distributed into the bacterial cytoplasm (Fig. 4A) without accumulation in the membranes. On the contrary, the fluorescence associated with PMB-BY was clearly present only on the cell surface (Fig. 4B). These data emphasize the difference in cellular distribution between Bac71-35-BY and PMB-BY and fully support the quenching results obtained by flow cytometry.

FIG. 4.

Confocal microscopy images of E. coli cells exposed to BODIPY-labeled peptides. E. coli HB101 cells were analyzed after incubation with 0.25 μM Bac71-35-BY (A) or 0.1 μM PMB-BY (B) for 60 min. Treated cells were washed four times with high-salt solution, and 10 μl was placed between two cover glasses to obtain an unmovable monolayer of cells. Unfixed bacterial cells were examined with a Nikon C1-SI confocal microscope with an oil immersion objective lens. All of the images are representative sections from the middle of the bacterial cell. Many fields were examined, and for each experiment, over 95% of the cells displayed the patterns of the respective representative cells shown here.

Overall, these results are consistent with the uptake and internalization of Bac71-35 by cells and are in agreement with previous observations obtained by immunoelectron microscopy (16). Conversely, the fluorescence intensity of E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium cells exposed to PMB-BY decreased by approximately 50%. This percentage is only slightly lower than that shown with a fluorescein-labeled antibody directed to the E. coli surface O and K antigens of lipopolysaccharide. In this case, over 70% of the fluorescence was quenched after TB addition (unpublished data). An accessibility of PMB-BY to the quencher similar to that of the surface-localized anti-lipopolysaccharide supports a surface localization of PMB. Interaction of this peptide with a compartment less accessible to TB, such as the lipid bilayer, might explain the small difference observed.

In summary, the method described here is suitable to rapidly screen the cell-penetrating capacity of peptides in bacteria and is useful in structure-activity relationship studies when many samples have to be compared. The assay can also be easily coupled to the PI uptake assay to investigate the permeabilizing capacity of the peptide under scrutiny (16). This would allow rapid determination of whether or not the mechanism of action of a specific AMP depends on membrane permeabilization. Finally, this method may also be applied to other nonpeptidic antibiotics to screen their cell-penetrating properties once they have been labeled with a suitable fluorophor.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Antcheva and G. Baj for technical assistance and A. Tossi for critically reading the manuscript. The free availability of the flow cytometry facility of the Fondazione Callerio ONLUS 132 is also gratefully acknowledged.

This study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry for University and Research (PRIN 2007) and from the Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia (grant under LR 26/2005, art. 23, for the R3A2 Network).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benincasa, M., M. Scocchi, E. Podda, B. Skerlavaj, L. Dolzani, and R. Gennaro. 2004. Antimicrobial activity of Bac7 fragments against drug-resistant clinical isolates. Peptides 25:2055-2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergström, F., I. Mikhalyov, P. Hagglof, R. Wortmann, T. Ny, and L. B. Johansson. 2002. Dimers of dipyrrometheneboron difluoride (BODIPY) with light spectroscopic applications in chemistry and biology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:196-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brogden, K. A. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:238-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cudic, M., and L. Otvos, Jr. 2002. Intracellular targets of antibacterial peptides. Curr. Drug Targets 3:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daugelavicius, R., E. Bakiene, and D. H. Bamford. 2000. Stages of polymyxin B interaction with the Escherichia coli cell envelope. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2969-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epand, R. M., and H. J. Vogel. 1999. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:11-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gennaro, R., M. Zanetti, M. Benincasa, E. Podda, and M. Miani. 2002. Pro-rich antimicrobial peptides from animals: structure, biological functions and mechanism of action. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8:763-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghiselli, R., A. Giacometti, O. Cirioni, R. Circo, F. Mocchegiani, B. Skerlavaj, G. D'Amato, G. Scalise, M. Zanetti, and V. Saba. 2003. Neutralization of endotoxin in vitro and in vivo by Bac71-35, a proline-rich antibacterial peptide. Shock 19:577-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gump, J. M., and S. F. Dowdy. 2007. TAT transduction: the molecular mechanism and therapeutic prospects. Trends Mol. Med. 13:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hed, J., G. Hallden, S. G. Johansson, and P. Larsson. 1987. The use of fluorescence quenching in flow cytofluorometry to measure the attachment and ingestion phases in phagocytosis in peripheral blood without prior cell separation. J. Immunol. Methods 101:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriques, S. T., J. Costa, and M. A. Castanho. 2005. Re-evaluating the role of strongly charged sequences in amphipathic cell-penetrating peptides: a fluorescence study using Pep-1. FEBS Lett. 579:4498-4502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriques, S. T., M. N. Melo, and M. A. Castanho. 2006. Cell-penetrating peptides and antimicrobial peptides: how different are they? Biochem. J. 399:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park, C. B., K. S. Yi, K. Matsuzaki, M. S. Kim, and S. C. Kim. 2000. Structure-activity analysis of buforin II, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide: the proline hinge is responsible for the cell-penetrating ability of buforin II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8245-8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel, L. N., J. L. Zaro, and W. C. Shen. 2007. Cell penetrating peptides: intracellular pathways and pharmaceutical perspectives. Pharm. Res. 24:1977-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrzykat, A., C. L. Friedrich, L. Zhang, V. Mendoza, and R. E. Hancock. 2002. Sublethal concentrations of pleurocidin-derived antimicrobial peptides inhibit macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:605-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Podda, E., M. Benincasa, S. Pacor, F. Micali, M. Mattiuzzo, R. Gennaro, and M. Scocchi. 2006. Dual mode of action of Bac7, a proline-rich antibacterial peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760:1732-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers, J. P., M. M. Martin, D. L. Goosney, and R. E. Hancock. 2006. The antimicrobial peptide polyphemusin localizes to the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli following treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1522-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahalan, A. Z., and R. A. Dixon. 2008. Role of the cell envelope in the antibacterial activities of polymyxin B and polymyxin B nonapeptide against Escherichia coli. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31:224-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scocchi, M., M. Mattiuzzo, M. Benincasa, N. Antcheva, A. Tossi, and R. Gennaro. 2008. Investigating the mode of action of proline-rich antimicrobial peptides using a genetic approach: a tool to identify new bacterial targets amenable to the design of novel antibiotics. Methods Mol. Biol. 494:161-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srimal, S., N. Surolia, S. Balasubramanian, and A. Surolia. 1996. Titration calorimetric studies to elucidate the specificity of the interactions of polymyxin B with lipopolysaccharides and lipid A. Biochem. J. 315(Pt. 2):679-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsubery, H., I. Ofek, S. Cohen, and M. Fridkin. 2000. The functional association of polymyxin B with bacterial lipopolysaccharide is stereospecific: studies on polymyxin B nonapeptide. Biochemistry 39:11837-11844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulvatne, H., O. Samuelsen, H. H. Haukland, M. Kramer, and L. H. Vorland. 2004. Lactoferricin B inhibits bacterial macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237:377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Amersfoort, E. S., and J. A. Van Strijp. 1994. Evaluation of a flow cytometric fluorescence quenching assay of phagocytosis of sensitized sheep erythrocytes by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cytometry 17:294-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walberg, M., P. Gaustad, and H. B. Steen. 1997. Rapid assessment of ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin susceptibility in exponentially-growing E. coli cells by means of flow cytometry. Cytometry 27:169-178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanetti, M. 2004. Cathelicidins, multifunctional peptides of the innate immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]