Abstract

Bacterial ABC transporters are an important class of transmembrane transporters that have a wide variety of substrates and are important for the virulence of several bacterial pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae. However, many S. pneumoniae ABC transporters have yet to be investigated for their role in virulence. Using insertional duplication mutagenesis mutants, we investigated the effects on virulence and in vitro growth of disruption of 9 S. pneumoniae ABC transporters. Several were partially attenuated in virulence compared to the wild-type parental strain in mouse models of infection. For one ABC transporter, required for full virulence and termed LivJHMGF due to its similarity to branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) transporters, a deletion mutant (ΔlivHMGF) was constructed to investigate its phenotype in more detail. When tested by competitive infection, the ΔlivHMGF strain had reduced virulence in models of both pneumonia and septicemia but was fully virulent when tested using noncompetitive experiments. The ΔlivHMGF strain had no detectable growth defect in defined or complete laboratory media. Recombinant LivJ, the substrate binding component of the LivJHMGF, was shown by both radioactive binding experiments and tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy to specifically bind to leucine, isoleucine, and valine, confirming that the LivJHMGF substrates are BCAAs. These data demonstrate a previously unsuspected role for BCAA transport during infection for S. pneumoniae and provide more evidence that functioning ABC transporters are required for the full virulence of bacterial pathogens.

Bacterial ABC transporters are an important class of transmembrane transporters that are involved in the import and export of a wide variety of substrates, including sugars, amino acids, peptides, polyamines, and cations (11, 12, 17, 39). A typical ABC transporter consists of four membrane-associated proteins consisting of two ATP-binding proteins (ATPases) and two membrane-spanning proteins (permeases) (11, 17). These may be fused in a variety of ways to form multidomain polypeptides, but typically permeases consist of six putative α-helical transmembrane segments that act as a channel through which substrates are transported across the membrane (11, 17). ABC transporters that import their substrate also contain a substrate-binding protein (SBP) that is present in the periplasm of gram-negative bacteria and most often as a lipoprotein bound to the outer surface of the membrane in gram-positive bacteria (17). These SBPs bind to the substrate before it is transferred across the cell membrane and therefore confer substrate specificity for the ABC transporter. Approximately 5% of the Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis genomes encode components of ABC transporters, highlighting the importance of ABC transporters for the physiology of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (12, 30). ABC transporters are known to influence many cellular processes. including antibiotic resistance, nutrient acquisition, adhesion, protein secretion, environmental sensing, spore formation, conjugation, and growth under stress conditions (39). As a consequence, many ABC transporters have been shown by signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) screens to be important for the virulence of a range of bacterial pathogens, including Yersinia spp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (9, 15, 22, 26), and these data have been supported by publications on the functions of individual ABC transporters (6, 7, 38, 45).

The annotated genome sequence of the TIGR4 strain of the common gram-positive pathogen S. pneumoniae contains 73 ABC transporters (4, 13). Several ABC transporters required for substrate uptake have been described in some detail previously, and some of these are known to be important for full virulence, including the cation transporters PsaA, PiuA, PiaA, and PitA (6, 7, 27, 34) and the polyamine transporter PotABCD (44). Why disruption of these ABC transporter functions affect virulence is probably due to a variety of mechanisms. These include effects on micronutrient acquisition under stress conditions, such as reduced iron uptake after disruption of PiuA, PiaA, and PitA; increased sensitivity to oxidative stress due to loss of polyamine or manganese uptake by PotABCD or PsaA, respectively (25, 43, 44); and impaired adhesion to cell surfaces related to disruption of PsaA (2, 20). In addition, since intracellular levels of cations and other micronutrients can influence gene regulation (20), impaired uptake of micronutrients could affect bacterial adaptation to the host environment. SBP components of ABC transporters are attached to the external surface of the bacterial membrane, where they are exposed to interactions with the environment, and their sequences are usually highly conserved between different strains of the same bacterial species. As a consequence, SBPs have been investigated as potential protein vaccine candidates, and PiuA, PiaA, PsaA, and PotD have all been shown to be effective vaccines in animal models at preventing S. pneumoniae infection (12, 23).

Given the importance of acquisition of various minerals and nutritional substrates for bacterial growth and virulence in vivo, some of the S. pneumoniae ABC transporters that have not yet been investigated are also likely to influence the pathogenesis of S. pneumoniae infections. Using mouse models of infection, we have therefore assessed the potential role during virulence of nine S. pneumoniae ABC transporters that have not, as far as we are aware, previously been investigated. Several ABC transporters were identified as required for full S. pneumoniae virulence in models of septicemia or pneumonia. The function of one of these ABC transporters, termed livJHMGF, which BLAST searches suggest is a member of the hydrophobic amino acid transporter subfamily and is likely to be a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) transporter (40), was investigated in more detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The E. coli strains DH5α, Novablue competent cells (Novagen), JM109 (Promega), and M15 (Qiagen) were used for cloning procedures. The capsular serotype 3 S. pneumoniae strain 0100993, originally isolated from a patient with pneumonia and obtained from SmithKline Beecham, Plc. (22), was used to construct S. pneumoniae mutant strains for the majority of the in vitro and in vivo phenotype analysis, with additional experiments performed using the capsular serotype 2 strain D39 and the serotype 4 strain TIGR4. E. coli was cultured at 37°C using Luria-Bertani broth or agar plates, and S. pneumoniae strains were cultured in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37°C on Columbia agar (Oxoid) supplemented with 5% horse blood (TCS Biosciences) or in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast-extract (Oxoid) or CDEM medium (42). Plasmids and mutant strains were selected for using appropriate antibiotics (10 μg of chloramphenicol, 100 μg of carbenicillin, and 25 μg of kanamycin ml−1 for E. coli and 10 μg of chloramphenicol and 0.2 μg of erythromycin ml−1 for S. pneumoniae). Stocks of S. pneumoniae were stored as single-use 0.5-ml aliquots of THY broth culture (optical density at 580 nm [OD580] of 0.3 to 0.4) at −70°C in 10% glycerol. The growth of S. pneumoniae strains in broth was monitored by measuring the OD580.

Nucleic acid manipulations and RT-PCR.

S. pneumoniae genomic DNA was extracted from bacteria grown in THY by using a modified Wizard genomic DNA kit (Promega), and RNA was extracted by using an SV total RNA extraction kit (Promega) as previously described (6). Restriction digests, ligation of DNA fragments, fractionation of DNA fragments by electrophoresis, and transformation of E. coli (by heat shock) were performed according to established protocols (33). DNA fragments were purified from electrophoresis gels by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit. Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed by using the Access RT-PCR system (Promega) and gene-specific primers (see Table 2). The National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) was used to perform BLAST searches and alignments of the available complete and incomplete bacterial nucleotide and protein databases. Primers for both PCR and RT-PCR were designed using sequences displayed by the Artemis software.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Sp0090.1 | GCTCTAGACATTGAGAGAGACAACTGG |

| Sp0090.2 | CGCTCTAGACAAGAAGTAAGGGAAC |

| Sp0149.1 | GCTCTAGAGGCTCTTGCAGCTTGCGG |

| Sp0149.2 | CGCTCTAGAGGCTTTCGTTTGTAGCGTC |

| Sp0610.1 | GCTCTAGATTACGGAGACTACCACG |

| Sp0610.2 | CGCTCTAGATCCACCAGATAGCATGCC |

| Sp0710.1 | GCTCTAGATTGGGCGTTACGATTG |

| Sp0710.2 | CGCTCTAGAGTGCCTGTCCACTTTC |

| Sp0750.1 | GCTCTAGACGCGCTGTTAGCCCTAGG |

| Sp0750.2 | GCTCTAGATGATACTGCACGCATGGC |

| Sp846.1 | GCTCTAGATGTTAGCAGGCCTTCTTG |

| Sp846.2 | CGCTCTAGAGCCCCTGCAATTTCAAC |

| Sp1690.1 | GCTCTAGATTGCGCTAGCGGCTGTTG |

| Sp1690.2 | GCTCTAGAGCTTCCTCCACCACTACG |

| Sp1798.1 | GCTCTAGATGACTGTCCCCGGTTTAG |

| Sp1798.2 | CGCTCTAGATTGTTGATTGGTCCTCCC |

| Sp1826.1 | GCTCTAGACGACTGCTTCTTCATCTG |

| Sp1826.2 | CGCTCTAGAATTGCCCGTCCTGTACC |

| Sp2084.1 | GCTCTAGATTTGGGCTTGTTGCCTG |

| Sp2084.2 | CGCTCTAGATGTGACCACTTGTTGACC |

| Sp2108.1 | GCTCTAGAACTGCTACACTTGCTAG |

| Sp2108.2 | CGCTCTAGAACCAAGGCTACCTAC |

| Cm.1 | TTATAAAAGCCAGTCATTAG |

| Cm.2 | TTTGATTTTTAATGGATAATG |

| Sp1 | TCGAGATCTATCGATGCA |

| Sp3 | GGATCCATATGACGTCGA |

| EryF | ATGAACAAAAATATAAAATA |

| EryR | TTATTTCCTCCCGTTAAATAAT |

| Sp0749F | CACTGACAATGCCAGTGACTATGC |

| Ery-Sp0749R | TATTTTATATTTTTGTTCATAAGATTCACTCTTTCTATTTATAA |

| Ery-Sp0753F | ATTATTTAACGGGAGGAAATAAAACATTCCAGTGGATTGTTTTAG |

| Sp0754R | GCGGAATATTGACTGTATGGGAG |

| Sp0749Fwd | CGGGATCCTGTGGAGAAGTGAAGTCTGGA |

| Sp0749Rv | CGGGATCCTTATGGTTTTACAACTTCTGC |

| Sp0749RT1 | CGATGCAGACCACAACAC |

| Sp750RT2 | CCTAGGGCTAACAGCGC |

| 750RT1.1 | GATGGGGGTTACTCCAGG |

| 751RT2.1 | CCCAGAGTTGCTACCGC |

| 751RT1.1 | GGTGCGATTGTTTCGG |

| 752RT2.1 | GGTTCCGTAGCAAGGG |

| Sp0752RT1 | GGCCGTTTAATCGCTCAAG |

| Sp0753RT2 | GGGCGCGTCCCATGGCAAG |

| 753RT1.1 | GGAGAATCGTCCTATCAG |

| 754RT2.1 | CAGGCAGACGGTGCAAACC |

Restriction enzyme sites in 5′ linkers are underlined.

Construction of S. pneumoniae mutant strains.

Strains and plasmids used for the present study are described in Table 1, and the primers used for PCR and sequencing are listed in Table 2. Strains containing disrupted copies of genes encoding ABC transporters were constructed by using insertional duplication mutagenesis (IDM) and the plasmid pID701 (22). Internal fragments of target genes were amplified by PCR from S. pneumoniae genomic DNA using primers designed from the TIGR4 genome sequence (Table 2) (http://www.tigr.org) (40). Amplified products were ligated into the XbaI site of pID701 and transformed into E. coli for amplification of plasmid DNA. Plasmids with the correct inserts were then used to transform S. pneumoniae strain 0100993 using competence stimulating peptide 1 (kindly provided by D. Morrison) and selection with chloramphenicol according to established protocols (6, 22).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids constructed and/or used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Description (source or reference)a |

|---|---|

| Plasmids | |

| pID701 | Shuttle vector for IDM transformation of S. pneumoniae: Cmr (22) |

| pPC110 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp0090 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC111 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp0149 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC112 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp0610 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC113 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp0710 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC114 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp1796 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC115 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp1824 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC116 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp0750 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC117 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp1690 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC118 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp0846 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC119 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp2084 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC120 | pID701 containing an internal portion of Sp2108 in the XbaI site: Cmr (this study) |

| pPC139 | pQE30 carrying full length livJ: Kmr Ampr (this study) |

| Strains | |

| 0100993 | S. pneumoniae capsular serotype 3 clinical isolate (22) |

| ΔSp0090 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC110: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp0149 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC111: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp0610 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC112: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp0750 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC116: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp0846 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC118: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp1690 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC117: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp1796 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC114: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp1824 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC115: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp2084 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC119: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔSp2108 | 0100993 containing an insertion made with plasmid pPC120: Cmr (this study) |

| ΔlivHMGF | 0100993 containing the livHMGF deletion construct: Ermr (this study) |

| T4ΔlivHMGF | TIGR4 containing the livHMGF deletion construct: Ermr (this study) |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Ermr, erythromycin resistance.

The ΔlivHMGF strain was constructed by overlap extension PCR (36) using a transformation fragment in which a contiguous fragment of S. pneumoniae genomic DNA from Sp0749 to Sp0754 had the genes livHMGF (Sp0750 to Sp0753) replaced by the erythromycin resistance cassette ery. Two products corresponding to 883 kb 5′ (primers Sp0749F and Ery-Sp0749R) and 833 kb 3′ (primers Ery-Sp0753F and Sp0754R) to livHMGF were amplified from S. pneumoniae genomic DNA by PCR carrying 3′ and 5′ linkers complementary to the 5′ and 3′ portion of the ery gene, respectively. ery was amplified from pACH74 using PCR and the primers EryF and EryR (21). Reaction conditions for amplifying these three fragments were as follows: a volume of 200 μl containing 100 pmol of primers, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs; Bioline), and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma) using an initial denaturing step at 94°C for 4 min, followed by a PCR cycle of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Cleaned individual PCR products were fused by using a two-step PCR, with an initial PCR to fuse the 5′-flanking DNA fragment with ery, followed by addition of the 3′-flanking DNA. The conditions for the first PCR were as follows: reaction volume of 20 μl containing 8.7 μl of nuclease free water, 1 μl of buffer, 1 μl of 2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 μl of 50 mM MgSO4, 0.2 μl of Taq polymerase (Bioline), and approximately 50 ng of each PCR product with no primers and an initial denaturing step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 10 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The conditions for the second PCR were as follows: a reaction volume of 100 μl containing 68.2 μl of nuclease-free water, 10 μl of buffer, 10 μl of 2 mM concentrations of dNTPs, 4 μl of 50 mM MgSO4, 100 pmol of primers Sp0749F and Sp0754R, 3 μl of unpurified PCR product from the first PCR, and 0.8 μl of Taq polymerase and an initial denaturing step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2.5 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 3 min. The fusion PCR products were then analyzed on a 1% agarose gel, and the desired DNA band was excised and purified by using Qiagen QIAquick columns and transformed into the S. pneumoniae 0100993, D39, and TIGR4 strains as described above (7, 22). Plasmid and S. pneumoniae mutant identities were confirmed by PCR using insert (Table 2) and plasmid-specific primers (Sp1 and Sp3), followed by sequencing of the PCR products (performed by Lark Technologies, Inc. [United Kingdom] or UCL Sequencing Services using the BigDye terminator technique and gene-specific PCR primers).

Expression and characterization of His6-LivJ lipoprotein.

The lipoprotein LivJ (Sp0749) was expressed in E. coli and purified by using an N-terminal His- tagged QIAexpressionist system (Qiagen). Primers Sp0749Fwd and Sp0749Rv amplified a full-length livJ (excluding the 5′ portion encoding the predicted N-terminal signal peptide), which was ligated into the pQE30 expression vector to make the plasmid pPC139 and transformed into E. coli strain M15. Protein expression was induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and native His6-LivJ purified using Ni-NTA affinity columns according to the QIAexpressionist manual. Purification products were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and shown to contain a ≥95% purity of protein of the expected size for His6-LivJ, and the identity of the recombinant protein was confirmed by peptide mass fingerprinting as reported previously (35).

[14C]leucine, [14C]isoleucine, and [14C]maltose uptake and binding assays.

Radioactive uptake assays were performed by the rapid filtration method as previously described (45) with minor modifications. S. pneumoniae strains were grown in THY medium until the OD620 reached 0.2 to 0.4. These experiments were performed using a capsular serotype 2 S. pneumoniae strain (D39) since the mucoid colonies of the capsular serotype 3 strain prevented effective pelleting of the bacteria for these assays. Bacteria were harvested at 13,000 × g for 20 min and resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 1 mM MgCl2 to an OD620 between 0.8 and 1.1. The uptakes of leucine, isoleucine, and maltose were determined in 1-ml assays containing 0.85 ml of bacterial cells and a final concentration of 25 μM maltose, isoleucine, or leucine containing 0.125 μCi of 14C-labeled substrate ([14C]isoleucine, [14C]leucine, and [14C]maltose; GE Healthcare, United Kingdom). Samples (150 μl) containing bacteria and radioactive and nonradioactive substrates were removed at various time intervals (0, 1, 2, and 3 min) and immediately filtered through glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/F) and washed twice with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer. The washed filters were placed in scintillation vials in 5 ml of Ready-Safe scintillation cocktail (Beckman Coulter), and the radioactivity was determined by using a Wallac 1214 RackBeta liquid scintillation counter. A bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Sigma Aldrich, United Kingdom) determined that an OD620 of 1 was equivalent to 0.238 mg of protein, and this figure was used to convert the radioactivity counts to nmol of solute per mg of protein.

For radioactive substrate binding assays, 100 μl of purified His6-LivJ (27.5 μg) was incubated with a 5 μM substrate containing 0.1 μCi of 14C-labeled ligand (GE Healthcare) and further incubated on ice for 10 min. To this mixture, 1 ml of saturated ammonium sulfate was added, followed by incubation on ice for 20 min, and then filtered onto glass fiber filter papers (GF/F; Whatman). The filters were then washed with 4 ml of saturated ammonium sulfate and dried for 5 min. The filters were allowed to equilibrate in Ready-Safe scintillation cocktail for 20 min, and the radioactivity was determined by using a Wallac 1214 RackBeta liquid scintillation counter (31).

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy.

Purified His6-LivJ was used for tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy using a Hitachi F-2500 spectrofluorimeter at an excitation wavelength of 280 nm (slit width, 3 nm) and an emission wavelength of 309 nm (slit width, 3 nm) (41). The assay was performed by adding test amino acids (Sigma) dissolved in 10 mM NaH2PO4 to 0.5 μM His6-LivJ in 1.5 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) in a sample cuvette maintained at 25°C in the spectrofluorimeter with continuous stirring. The slit width of the spectrofluorimeter was adjusted to reduce photobleaching of the protein (41).

Animal models of infection.

Infection experiments were performed in age- and sex-matched groups of outbred CD1 mice (Charles River Breeders) between 4 to 8 weeks old. For mixed infections, equivalent numbers of bacteria from stocks of wild-type and mutant S. pneumoniae strains were mixed and diluted to the appropriate concentration. For the nasopharyneal colonization model, 107 CFU of bacteria in 10 μl were administered by intranasal (i.n.) inoculation under halothane general anesthesia, and nasal washes were obtained after 2 days. For the systemic model of infection, 103 CFU of bacteria in 100 μl were inoculated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, and spleen homogenates were obtained at 24 h (6, 21). For the pneumonia model, 5 × 106 CFU of bacteria in 40 μl were given by i.n. inoculation under halothane general anesthesia, and lung and spleen homogenates were obtained at 48 h (8, 21). Aliquots from samples recovered from mice were plated on plain and Cm containing plates to allow calculation of a competitive index (CI). The CI was calculated as follows: the ratio of mutant to wild-type strain recovered from mice divided by the ratio of mutant to wild-type strain in the inoculum (5). A CI of <1 indicates that the mutant strain is attenuated in virulence compared to the wild-type strain, and the lower the CI the more attenuated the mutant strain. Similar experiments were performed with a pure inocula of wild-type or ΔlivHMGF strain bacteria to calculate the bacterial CFU for each strain at specific time points or to monitor the progress of infection identifying mice likely to progress to fatal disease according to previously established criteria (6).

Statistical analysis.

All of the in vitro growth curves were performed in triplicates and are represented as means and standard deviations. The results of growth curves, radioactive uptake, and binding assays were analyzed by using two-tailed Student t tests. The results of survival experiments were compared by using the log-rank method, and target organ CFU levels were analyzed by using the Mann-Whitney U test. The statistical validity of the results for CIs is represented by 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS

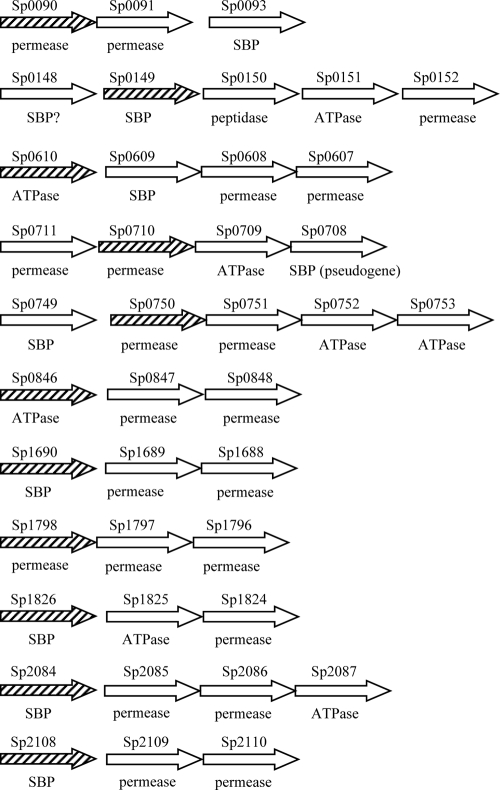

Selection of ABC transporters for investigation.

The ABC transporters chosen for these studies were identified from the annotated genome of the capsular serotype 4 strain of S. pneumoniae (TIGR4) (40). This genome contains 24 loci consisting of three or more adjacent genes that encode putative components of ABC transporters and are likely to be transcribed as an operon, 10 of which have been previously investigated. Eleven of the previously undescribed ABC transporters present in the TIGR4 genome of S. pneumoniae were selected for further investigation (Sp0090-3, Sp0148-52, Sp0607-10, Sp0708-11, Sp0749-53, Sp0846-8, Sp1688-90, Sp1796-8, Sp1824-6, Sp2084-7, and Sp2108-10). The results of BLAST searches using the derived amino acid sequence for each gene within the putative operons are shown in Table 3. Most of these ABC transporter proteins have >90% identity and similarity at the amino acid level to proteins encoded by genes in the S. pneumoniae R6 strain, an avirulent laboratory strain of S. pneumoniae derived from a capsular serotype 2 strain. However, there are no homologues of the Sp1796-8 operon in the R6 genome, and BLAST searches versus the 18 other available S. pneumoniae genomes demonstrated that the Sp1796-8 operon was also absent from the genomes of a further five strains (CDC1087-00, D39, G54, Hungary 19A-6, and Sp23-BS72). In contrast, the SBPs for almost all of the remaining ABC transporters were highly conserved between S. pneumoniae strains, with 97% or greater levels of identity between the deduced amino acid sequence of the TIGR4 SBP with the sequence of the equivalent SBP for all 19 S. pneumoniae strains with available genome data. The exception was Sp1826, which had between 93 and 95% identity to proteins encoded by genes present in 18 strains and 99% identity to the remaining strain (CDC0288-44). As expected, the majority of the predicted proteins have at least 50% identity and 60% similarity to proteins encoded by other streptococci (Table 3). In contrast, the genes in the putative Sp1688-90, Sp1824-26, and Sp2084-87 operons have no close homologues in streptococci. Sp1688-90 has >70% identity and >85% similarity to the amino acid sequence of predicted proteins encoded by Pm1760-62 of the gram-negative bacteria Pasteurella multocida, and Sp1824-26 and Sp2084-87 both have lower levels of identity and similarity to predicted proteins from a variety of unrelated bacteria. The mean G+C contents of Sp1688-90 and Sp1824-6 are 37 and 33.5%, respectively, which is significantly lower than the G+C content of the complete genome of TIGR4 (39.7%) (6, 40). The mean G+C content of Sp2084-7 was 39.0%, which is not significantly different from that of the complete genome of TIGR4. These data suggest that Sp1688-90, Sp1824-6, and possibly Sp2084-7 are contained within regions of the S. pneumoniae genome that could have been acquired by horizontal transfer from an unrelated species.

TABLE 3.

BLAST alignments of the derived amino acid sequences of the investigated S.pneumoniae ABC transporters

| Locus taga | Size (no. of amino acids) | Protein | Organism | % Identity/similarityb | Possible substrate (transport classification)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp0090 | 319 | EfaeDRAFT_2526 | Enterococcus faecium | 61/80 (311) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp0091 | 307 | EfaeDRAFT_2527 | Enterococcus faecium | 60/79 (300) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp0092 | 491 | EfaeDRAFT_2538 | Enterococcus faecium | 53/70 (486) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp0148 | 276 | SMU.1942c | Streptococcus mutans | 55/76 (237) | Methionine (MUT 3.A.1.24) |

| Sp0149 | 284 | SPs1626 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 67/81 (278) | Methionine (MUT 3.A.1.24) |

| Sp0150 | 457 | SMU.1940c | Streptococcus mutans | 70/85 (457) | Methionine (MUT 3.A.1.24) |

| Sp0151 | 353 | SsiuDRAFT_0064 | Streptococcus suis | 80/90 (352) | Methionine (MUT 3.A.1.24) |

| Sp0152 | 230 | SPs1624 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 71/89 (230) | Methionine (MUT 3.A.1.24) |

| Sp0607 | 219 | SMU.1522 | Streptococcus mutans | 74/85 (213) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0608 | 219 | SMU.1521 | Streptococcus mutans | 62/81 (222) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0609 | 254 | StheL01000593 | Streptococcus thermophilus | 60/73 (232) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0610 | 252 | StheL01000592 | Streptococcus thermophilus | 82/90 (251) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0708 | 215 | SsuiDRAFT_0032 | Streptococcus suis | 60/77 (209) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0709 | 252 | SGO_0983 | Streptococcus gordonii | 88/94 (252) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0710 | 225 | SGO_0984 | Streptococcus gordonii | 89/95 (225) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0711 | 206 | SGO_0985 | Streptococcus gordonii | 87/94 (226) | Amino acid (PAAT 3.A.1.3) |

| Sp0749 | 386 | SAG1582 | Streptococcus agalactiae | 53/73 (390) | BCAA (HAAT 3.A.1.4) |

| Sp0750 | 289 | SAK_1597 | Streptococcus agalactiae | 83/93 (289) | BCAA (HAAT 3.A.1.4) |

| Sp0751 | 318 | gbs1630 | Streptococcus agalactiae | 73/88 (252) | BCAA (HAAT 3.A.1.4) |

| Sp0752 | 254 | SsuiDRAFT_0078 | Streptococcus suis | 85/93 (254) | BCAA (HAAT 3.A.1.4) |

| Sp0753 | 236 | SsuiDRAFT_0077 | Streptococcus suis | 87/96 (236) | BCAA (HAAT 3.A.1.4) |

| Sp0846 | 511 | Spy1227 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 81/91 (508) | Ribonucleoside (CUT2 3.A.1.2) |

| Sp0847 | 352 | SAK_1051 | Streptococcus agalactiae | 77/88 (353) | Ribonucleoside (CUT2 3.A.1.2) |

| Sp0848 | 318 | Spy0928 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 80/92 (318) | Ribonucleoside (CUT2 3.A.1.2) |

| Sp1688 | 277 | PM1760 | Pasteurella multocida | 80/91 (277) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp1689 | 294 | PM1761 | Pasteurella multocida | 79/93 (291) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp1690 | 445 | PM1762 | Pasteurella multocida | 70/85 (407) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp1796 | 538 | SsuiDRAFT_0524 | Streptococcus suis | 78/89 (537) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp1797 | 305 | SsuiDRAFT_0525 | Streptococcus suis | 82/94 (294) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp1798 | 305 | SsuiDRAFT_0526 | Streptococcus suis | 84/95 (303) | Sugar (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp1824 | 563 | Lxx14070 | Leifsonia xyli | 31/48 (539) | Cation 2 (BIT 3.A.1.0) |

| Sp1825 | 336 | STH2752 | Symbiobacterium thermophilum | 45/59 (343) | Cation 2 (BIT 3.A.1.0) |

| Sp1826 | 355 | Lxx14040 | Leifsonia xyli | 30/48 (323) | Cation 2 (BIT 3.A.1.0) |

| Sp2084 | 291 | RUMOBE_00498 | Ruminococcus obeum | 46/65 (287) | Phosphate (PhoT 3.A.1.7) |

| Sp2085 | 287 | Cthe_1604 | Clostridia thermocellum | 61/98 (284) | Phosphate (PhoT 3.A.1.7) |

| Sp2086 | 271 | DORLON_00312 | Dorea longicatena | 59/80 (287) | Phosphate (PhoT 3.A.1.7) |

| Sp2087 | 250 | BACCAP_00261 | Bacteroides capillosus | 72/86 (253) | Phosphate (PhoT 3.A.1.7) |

| Sp2108 | 423 | M_28Spy1048 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 53/67 (420) | Maltodextrin (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp2109 | 435 | Spy1301 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 66/82 (430) | Maltodextrin (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

| Sp2110 | 280 | SsuiDRAFT_0440 | Streptococcus suis | 85/93 (280) | Maltodextrin (CUT1 3.A.1.1) |

That is, the TIGR4 genome locus tag number.

The length, in amino acids, compared is indicated in parentheses.

Transport classification and subfamily and number according to the transport classification system based on sequence similarity (32, 45; see also http://www.tcdb.org/).

Construction of ABC transporter mutant strains.

To investigate the role of the selected ABC transporters during in vivo growth and virulence, mutant strains of the 0100993 strain of the capsular serotype 3 S. pneumoniae were constructed by using IDM. Mutations were designed to disrupt one gene, usually the first, within the putative operon of each ABC transporter (Fig. 1) and were successfully obtained for 10 of the 11 chosen ABC transporters. Although the disruption construct was made successfully, no mutants were obtained by disrupting Sp0710 despite repeated transformations. The stability of each mutation was assessed by culturing the mutant strains in THY broth in the absence of antibiotic (and therefore selective pressure) for two 8-h growth cycles, followed by plating onto plain and antibiotic plates. The Sp2084− mutation was unstable (19 chloramphenicol-resistant colonies recovered compared to >1,000 on plain plates), preventing further investigation of this mutant, whereas the mutations in the remaining mutant strains were stable with similar numbers of colonies on the plain and antibiotic plates. All of the mutant strains had similar growth in THY compared to the wild-type strain when measured by monitoring the OD580 over time (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the organization of loci encoding ABC transporter components investigated in the present study. Each arrow represents a single gene, which are not drawn to scale. Gaps between genes correspond to gaps of greater than 50 bp between the stop codon of the upstream gene and the ATG of the downstream gene. The TIGR4 gene number is given above each gene, and whether the gene encodes a putative SBP, ATPase or membrane protein (permease) is written beneath. The diagonally shaded gene in each locus (▒) was targeted by IDM using pID701 containing an internal portion of the target gene.

Phenotypes of mutant strains containing disruptions in genes encoding ABC transporters.

The phenotypes of the mutant strains were investigated using mixed inocula and CIs to identify subtle defects affecting in vitro growth and to assess their virulence compared to the wild-type strain in animal models of infection. CIs were obtained for growth in complete medium (THY) and a physiologically relevant fluid (human blood) and in mouse models of pulmonary and systemic infection using bacteria recovered from the lungs and spleen, respectively, to calculate the CI (Table 4). We were unable to establish a nasopharyngeal colonization model for the serotype 3 strain in which the mutants were constructed, preventing assessment of the role of these ABC transporters during colonization. Most of the mutants had CIs close to 1.0 in THY, suggesting that disruption of the target ABC transporters had no effect on growth in complete medium. The exception was ΔSp0750 which had mildly impaired growth in THY. In contrast, in normal physiological fluid such as human blood, the mutants ΔSp0090, ΔSp0149, ΔSp0750, ΔSp1824, and (to a lesser extent) ΔSp0610 had reduced CIs, suggesting that these mutants have a particular problem growing in physiological fluid compared to THY. The in vivo CIs for most mutant strains mirrored the CIs for growth in blood, with these strains showing no impairment in CI in blood also being fully virulent (ΔSp0846, ΔSp1690, and ΔSp1796), whereas strains with impaired CIs in blood also had a reduced CI during infection. These data indicate that for these mutant strains, impaired growth under physiological conditions is associated with a reduced ability to cause invasive infection. In addition, ΔSp2108 had some impairment in virulence after i.p. inoculation without any impairment in CI in growth in blood. For both systemic and pulmonary infections, the ΔSp0750 and ΔSp0149 strains were markedly more attenuated in virulence than the other mutant strains with a CI reduced out of proportion to the reduced CI in blood.

TABLE 4.

In vitro and in vivo phenotype analysis of S. pneumoniae ABC transporter mutant strains using CI valuesa

| Strain | CI (95% confidence interval) with various sample types

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THY | Blood | i.p. | i.n. | |

| ΔSp0090 | 1.10 (0.24-2.0) | 0.39 (0.31-0.47) | 0.49 (0.37-0.61) | 0.43 (0.23-0.63) |

| ΔSp0149 | 0.95 (0.67-1.22) | 0.46 (0.37-0.57) | 0.067 (0.031-0.10) | 0.041 (0.021-0.10) |

| ΔSp0610 | 1.40 (1.02-1.77) | 0.71 (0.58-0.83) | 0.70 (0.53-0.86) | 0.64 (0.15-1.20) |

| ΔSp0750 | 1.06 (0.86-1.25) | 0.40 (0.20-0.60) | 0.17 (0.078-0.26) | 0.018 (0.002-0.032) |

| ΔSp0846 | 0.95 (0.67-1.22) | 1.25 (0.90-1.60) | 0.61 (0.22-1.00) | 0.54 (0.30-0.79) |

| ΔSp1690 | 0.97 (0.77-1.18) | 0.92 (0.56-1.27) | 0.89 (0.41-1.38) | NDb |

| ΔSp1796 | 0.82 (0.59-1.04) | 0.78 (0.56-0.99) | 1.30 (0.93-1.71) | ND |

| ΔSp1824 | 0.95 (0.25-1.65) | 0.66 (0.43-0.89) | 0.59 (0.34-0.84) | 0.33 (0.01-0.67) |

| ΔSp2108 | 1.05 (0.71-1.40) | 1.25 (0.92-1.57) | 0.39 (0.29-0.49) | 1.00 (0.36-1.64) |

For mouse experiments, n = 3 to 10.

ND, not done.

Construction of a deletion mutant of Sp0750-53.

The data obtained with the disruption mutant strains suggested that the ABC transporters encoded by Sp0149-52 and Sp0749-53 have the most crucial roles during S. pneumoniae infection (Table 4). BLAST alignments of the predicted proteins encoded by Sp0149-52 suggested these genes encode a methionine ABC transporter protein, but the function of this ABC transporter was not investigated further at this stage (37). BLAST alignments of Sp0749-53 showed the proteins encoded by these genes have high levels of similarity to predicted BCAA ABC transporter proteins (Table 3), clearly indicating the likely function of this ABC transporter. Auxotrophy for BCAA due to mutations affecting BCAA synthesis has been shown to affect the virulence of Mycobacterium bovis and Burkholderia pseudomallei (3, 24) but, as far as we are aware, no role has yet been described for BCAA transporters in bacterial virulence. We therefore elected to investigate the Sp0749-53 transporter in more detail and have named the genes livJHMGF to correspond to their E. coli orthologues (1).

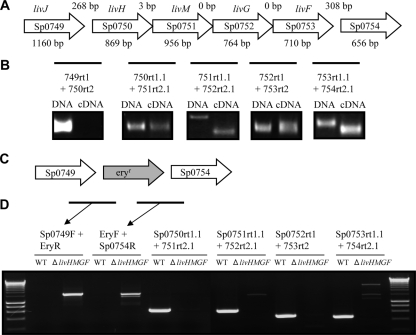

To confirm the genetic organization of Sp0749-0753, RT-PCR was performed using RNA from strain 0100993 as the template and primers designed to amplify a product that spans the junctions of the genes present in the putative operon (Table 2). The lack of DNA contamination was confirmed by the absence of products for reactions with no added RT enzyme (data not shown), and RT-PCR products were sequenced to confirm their identities. The livJHMGF/Sp0749-53 region is 4,831 bp in length and consists of five genes, livJ/Sp0749 (encoding an SBP lipoprotein), livH/Sp0750 (encoding a membrane protein permease), livM/Sp0751 (encoding a membrane protein permease), livG/Sp0752 (encoding an ATPase) and livF/Sp0753 (encoding an ATPase) (Table 3 and Fig. 2A). The RT-PCR results matched with the operon structure deduced from the TIGR4 genome sequence, suggesting that livJ is not cotranscribed with livH (corresponding to the relatively large intergenic region between these two genes of 268 bp) and that livH, livM, livG, and livF are all cotranscribed (Fig. 2A and B). Although the RT-PCR product obtained using primers spanning the junction of livM and livG was smaller than the expected size, sequencing confirmed it represented a product of the 5′ region of livM and 3′ region of livG and conformed exactly in length and almost exactly in nucleotide sequence to that predicted from the genome data for the TIGR4 strain. RT-PCR between livF and Sp0754 did generate a cDNA fragment, but sequencing demonstrated this was a nonspecific product. For further investigation of the function of livJHMGF, a mutant strain in the S. pneumoniae 0100993 background was constructed in which livHMGF were deleted using a construct made by overlap extension PCR (Fig. 2C and D). Correct deletion of these genes in the ΔlivHMGF mutant strain was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

FIG. 2.

(A) Structure of the livJHMGF locus. Each arrows represents one gene and contains the Sp number within the arrow and the gene annotation above the arrow. The size in base pairs of each gene is given below the arrow, and the number of base pairs between the stop codon of the upstream gene and the ATG of the downstream gene is given above the arrows in the corresponding gap. (B) Results of RT-PCR assessment of the transcriptional linkage between the livJHMGF genes. The bar represents the target product relative to the genes shown in panel A for each primer pair (named beneath the bar). A picture of the ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels showing the PCR products obtained using these primers and either DNA or cDNA as the template is given with each primer pair. (C) Representation of the structure of the livJHMGF locus in the ΔlivHMGF strain. (D) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels showing the PCR products obtained from the ΔlivHMGF and wild-type strain, confirming replacement of the livHMGF with the erythromycin resistance cassette (eryr in the figure) in the ΔlivHMGF strain. Bars represent expected products for the primer pairs given above the lanes for their corresponding PCR products.

In vivo phenotypes of the ΔlivHMGF mutant strain.

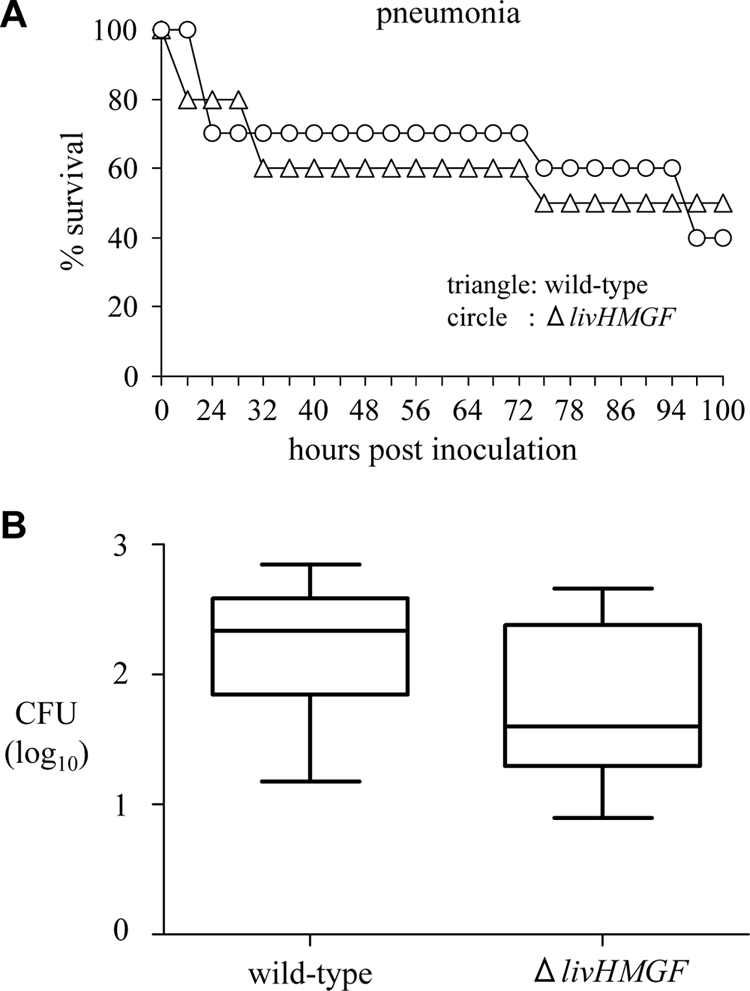

To investigate the effect of deletion of livHMGF on the virulence of S. pneumoniae, CIs were determined in the pulmonary and systemic mouse models of infection. The CIs for the ΔlivHMGF deletion mutant were reduced in models of pneumonia and septicemia showing a significant attenuation in virulence in these models of infection (Table 5), although the results were higher than those obtained with the ΔSp0750 IDM mutant strain (Table 4). CIs were also obtained for a ΔlivHMGF strain in the TIGR4 background in models of nasopharyngeal colonization, systemic infection, and pneumonia (Table 5). The TIGR4 ΔlivHMGF strain was significantly attenuated in virulence in the pneumonia model but not in the nasopharyngeal colonization model and, in contrast to the serotype 3 0100993 ΔlivHMGF strain, had only a statistically not significant (the confidence intervals overlapped with 1.0) small decrease in the CI for the systemic model of infection. To assess the ability of the ΔlivHMGF S. pneumoniae strain to cause fatal disease, groups of 10 CD1 mice strain were inoculated i.n. with 107 CFU of the wild-type S. pneumoniae 0100993 strain or the ΔlivHMGF deletion strain, and the progress of infection was monitored (6) (Fig. 3A). There was no difference in the survival of mice inoculated with the wild-type and ΔlivHMGF strains, demonstrating that despite the impaired virulence of the ΔlivHMGF strain when in competition with the wild-type strain this strain is still able to cause fatal disease. In addition, bacterial CFU in mouse lungs culled 48 h after inoculation of either the wild-type or ΔlivHMGF strains were not significantly different (Fig. 3B). These data show that the loss of LivJHMGF only impairs virulence significantly in a competitive model of infection.

TABLE 5.

In vivo phenotype analysis of the ΔlivHMGF S. pneumoniae strains compared to the wild-type strain using CI values for three different serotype backgroundsa

| Capsular serotype | CI (95% confidence interval) obtained by various routes

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n.p. (nasal wash) | i.n. (lung) | i.p. (spleen) | |

| 3 | NDb | 0.11 (0.004-0.58) | 0.076 (0.040-0.094) |

| 4 | 1.05 (0.68-1.41) | 0.018 (0.001-0.34) | 0.62 (0.16-1.08) |

For these experiments, n = 5 to 10. n.p., nasopharyngeal.

ND, not done (there was no nasopharyngeal model for this strain).

FIG. 3.

Assessment of the virulence of the ΔlivHMGF strain in mouse models of infection. (A) Time course for the development of fatal infection for groups of 10 mice given 5 × 106 CFU of either the wild-type or the ΔlivHMGF strain (P = 0.88, log-rank test). (B) Log10 ml−1 bacterial CFU recovered from the lungs of mice 24 h after inoculation with 5 × 106 CFU of either the wild-type or ΔlivHMGF strain. The results are shown as box-and-whisker diagrams of the median log10 ml−1 bacterial CFU and the interquartile range for data obtained from two identical experiments, each with five mice per strain.

In vitro phenotypes of the ΔlivHMGF strain.

When compared using the OD580, the growth of the ΔlivHMGF mutant strain was similar to the growth of the wild-type strain in THY and in a defined chemical medium CDEM with or without supplementation with the BCAAs valine, isoleucine, or leucine (data not shown). As shown for the ΔSp0750 IDM mutant strain (Table 4), the CI of the ΔlivHMGF mutant strain compared to the wild-type strains in vitro after growth in blood was impaired (CI = 0.56, confidence intervals of 0.34 to 0.78), but this was not corrected by the addition of 10 mg of valine, isoleucine, or leucine/ml impaired (CI = 0.44, confidence intervals of 0.15 to 0.74). Uptake of azaleucine by BCAA ABC transporters causes toxicity and impaired growth of gram-negative bacteria (14, 18), which is reduced if BCAA uptake is inactivated. However, azaleucine in concentrations of up to 100 μg ml−1 was not toxic to S. pneumoniae (data not shown), and azaleucine toxicity could not therefore be used to assess BCAA uptake. Furthermore, attempts to confirm that livJHMGF does encode an BCAA ABC transporter by comparison of leucine and isoleucine uptake by the wild-type and ΔlivHMGF strains were unsuccessful. Although significant uptake of the positive control substrate maltose was demonstrated for both the wild-type and the ΔlivHMGF strains, no significant uptake of [14C]leucine (Table 6) or [14C]isoleucine (data not shown) could be detected under these experimental conditions even by the wild-type strain, precluding the use of uptake assays to assess the function of LivJHMGF.

TABLE 6.

[14C]leucine and [14C]maltose uptake by wild-type and ΔlivHMGF strains

| Strain | Substrate | Uptake (mmol/mg of protein) at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 s | 120 s | 180 s | ||

| Wild type | [14C]leucine | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.35 |

| [14C]maltose | 12.8 | 30.4 | 40.4 | |

| ΔlivHMGF | [14C]leucine | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.71 |

| [14C]maltose | 13.0 | 32.7 | 44.6 | |

LivJ is a BCAA binding protein.

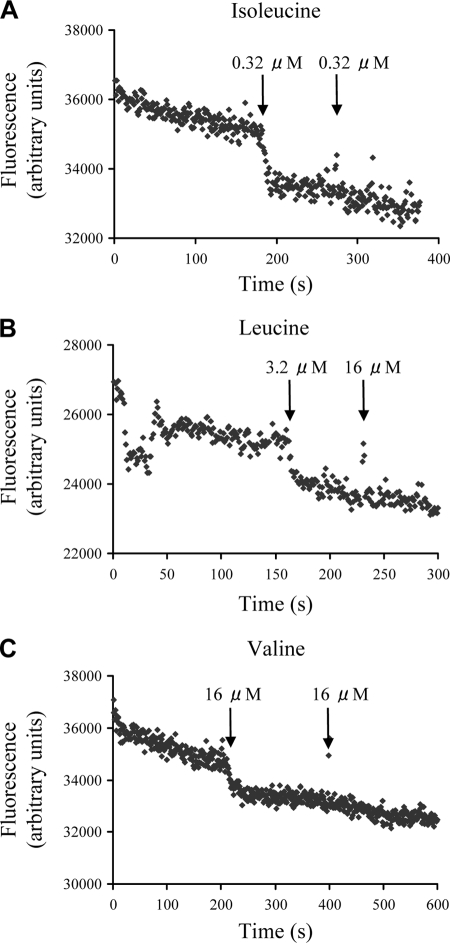

Since the SBP component provides substrate specificity for ABC transporters, to identify the substrate(s) of the LivJHMGF ABC transporter the binding of labeled amino acids to the LivJ (Sp0749) SBP was assessed. An N-terminally histidine-tagged LivJ (His6-LivJ) was expressed in E. coli and purified to ca. 95% purity. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis demonstrated that most of the purified protein was found in a single band of ∼40 kDa, which is compatible with the expected mass for His6-LivJ. There was an additional band with a mass of ∼80 kDa. Peptide mass fingerprinting confirmed that the 40-kDa band was His6-LivJ and that the 80-kDa band consisted of a dimer of His6-LivJ. The ligand-binding properties of His6-LivJ were investigated by measuring changes in intrinsic protein fluorescence, using tyrosine fluorescence (excitation at 280 nm) since the protein lacks any tryptophan residues. We were able to observe small but reproducible protein-dependent fluorescence changes in His6-LivJ upon the addition of 0.32 μM isoleucine, 3.2 μM leucine, and 16 μM valine (Fig. 4). There was no further fluorescence change with the addition of excess ligand, suggesting binding was saturated (Fig. 4). There were also no changes in fluorescence with the addition of 50 μM concentrations of the non-BCAAs proline, glycine, and alanine (data not shown). To estimate a relative affinity of the protein toward these three BCAAs, the lowest concentration of ligand for which we could detect a fluorescence change over the slow decrease in signal due to photobleaching was determined. Using 1.6 μM concentrations of ligand we could only detect isoleucine and leucine binding, and using 0.32 μM concentrations of ligand we could only detect isoleucine binding (Fig. 4 and data not shown). These data suggest that LivJ (Sp0749) is able to bind BCAA with a preference for isoleucine over leucine over valine and that the protein is likely to bind isoleucine in the submicromolar range that is typical for the physiological substrate of other ABC transporters.

FIG. 4.

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy of purified His6-LivJ after addition of 0.32 μM isoleucine (A), 3.2 μM leucine (B), or 16 μM valine (C) (marked by the first arrow). The addition of excess ligand (marked by the second arrow) had no further effect on fluorescence, nor did the addition of 50 μM proline, glycine, or alanine (data not shown). Fluorescence was measured by using arbitary units and an excitation wavelength of 280 nm with an emission wavelength of 309 nm.

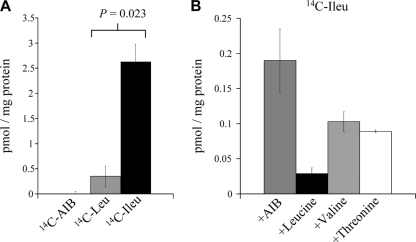

The ligand-binding properties of His6-LivJ were also investigated by using a radioactive binding assay. The His6-LivJ lipoprotein bound to [14C]isoleucine and to a lesser extent [14C]leucine but not to the negative control ligand [α-14C]aminoisobutyric acid (AIB) (Fig. 5A). Competitive binding experiments using putative ligands to inhibit [14C]isoleucine binding to His6-LivJ protein demonstrated that leucine and, to a lesser extent, valine and threonine inhibited [14C]isoleucine binding (Fig. 5B). Overall, the results of the fluorescence and radioactive binding studies show that the substrates of the S. pneumoniae LivJHMGF ABC transporter are BCAAs, with high-affinity binding of LivJ to isoleucine, moderate affinity binding to leucine and the least affinity toward valine.

FIG. 5.

Radioactive binding assays to purified His6-LivJ. (A) Degree of binding of 14C-AIB (negative control) and the BCAAs [14C]leucine and [14C]isoleucine to His6-LivJ expressed as pmol of substrate per mg of His6-LivJ. No significant binding to AIB was detected. For the differences between [14C]leucine and [14C]isoleucine, P = 0.023 (Student t test). (B) Competitive blocking of [14C]isoleucine binding to His6-LivJ by the addition of excess (500 μM) AIB, leucine, valine, or threonine. Compared to AIB, P = 0.005 for leucine, 0.014 for valine, and <0.001 for threonine. Compared to leucine, P < 0.05 for both valine and threonine (one-way analysis of variance).

DISCUSSION

Genes encoding components of ABC transporters make up a significant portion of many bacterial genomes, including S. pneumoniae (12, 40). Through controlling uptake or export of a wide range of substrates, ABC transporters have a central role in modulating the bacterial interactions with the environment, including the host for pathogens. Hence, it is perhaps not surprising that STM screens for virulence determinants frequently have identified ABC transporters (9, 10, 15, 22, 26) and that detailed characterization of individual S. pneumoniae ABC transporters have shown that several affect the development of infection through a variety of mechanisms (6, 17, 27, 34, 44). We have screened 11 S. pneumoniae ABC transporters that have not, as far as we are aware, previously been investigated for their roles in virulence. Mixed infections and CIs are highly sensitive at identifying virulence defects and only require relatively small numbers of animals and so were used to assess the relative virulence of mutant strains containing disrupted ABC transporter genes to the wild-type strains (5, 6). We were unable to obtain any mutants affecting the putative amino acid transporter encoded by Sp0707-0711, perhaps since this transporter is important for S. pneumoniae viability, and the insertional duplication mutant affecting the putative phosphate transporter encoded by Sp2084-2087 was too unstable for further investigation. Of the nine ABC transporter mutant strains successfully constructed, six were impaired in full virulence in mouse models of sepsis and/or pneumonia (ΔSp0090, ΔSp0149, ΔSp0610, ΔSp0750, ΔSp1824, and ΔSp2108). Their putative roles included sugar, cation, BCAA, and other amino acid transport, and for the majority the CIs in blood were similar to the CIs in the infection model, suggesting that their effects on virulence are likely to be due to their role during growth under physiological conditions. These results indicate that ABC transporters frequently influence S. pneumoniae disease pathogenesis, demonstrating why mutations affecting lipoprotein and therefore SBP processing by S. pneumoniae affect virulence (21, 29). The majority of the loci encoding ABC transporters investigated in the present study have equivalents in other streptococci, and it is likely that some of these will also be required for full virulence.

For four of the ABC transporter mutant strains the impairment in virulence was relatively small, comparable to the effect of the loss of a single iron transporter (17), and this may be because their functions are partially redundant. For example, BLAST alignments suggest that several of the ABC transporters we have investigated encode sugar transporters, and disrupting the function of one could be compensated for by the others or even by non-ABC transporter uptake mechanisms such as phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar transporters (40). In addition, in the host there are a variety of sugar substrates available, and the inability of S. pneumoniae to use a single sugar due to impaired uptake may not be critical due to the availability of other sugars. Dual mutations in genes encoding components of ABC transporters with related functions may have a much more marked effect on virulence as has been shown for the Piu and Pia iron transporters (6). However, too few functional data on the ABC transporters were investigated here to be able to determine which ABC transporters should be selected for dual mutation. The effects of disruption of these ABC transporters on virulence indicates bacterial functions that are likely to be important during infection, which our data suggest includes sugar, amino acid, and cation uptake. Although cation uptake is a well-recognized requirement for the virulence of S. pneumoniae and other bacteria (6, 17, 20, 25), sugar and amino acid transport is less well recognized. Identification of the specific substrate for each transporter will help define the precise physiological requirements for S. pneumoniae virulence but will require painstaking screening of a range of potential substrates using in vitro phenotypes and binding and uptake assays. In addition to ABC transporters encoded for by groups of genes investigated in this and previous studies, there are many additional ABC transporter components encoded by isolated single genes or gene pairs within the TIGR4 genome, some of which STM screens suggest may affect virulence (15, 22). These ABC transporter components also warrant further investigation, although their specific putative functions will in general be even less apparent than those encoded by several adjacent genes in putative operons.

Two mutant strains had a marked effect on virulence when analyzed using CIs. One contained a disrupted copy of Sp0149, part of a potential methionine transporter which is the subject of continued investigation in our laboratory. The second contained a disrupted copy of Sp0750, part of an operon whose function is strongly indicated by BLAST searches to be BCAA uptake. The genes at the Sp0749-53 loci are annotated as livJHMGF in the TIGR4 genome (40) and are organized in a fashion similar to that of the equivalent BCAA of E. coli, with the SBP component encoded by livJ that is transcribed as a separate transcript to the remaining genes within the operon livHMGF (19). Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy and radioactive binding assays using [14C]leucine, [14C]isoleucine, and [14C]valine demonstrated that LivJ binds specifically to BCAA, strongly supporting that livJHMGF encodes a BCAA ABC transporter. Both the tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy and the radioactive binding assays suggest that LivJ has the highest affinity for isoleucine and then leucine, with the least affinity for valine.

Growth of the ΔlivHMGF strain was not affected in media depleted in BCAA, the toxic BCAA analogue azaleucine did not impair S. pneumoniae growth, and we were unable to identify significant uptake of the BCAA leucine by S. pneumoniae. Hence, in the conditions used for these experiments (i.e., the complete medium THY and the defined medium CDEM) there seems to be very little BCAA uptake by S. pneumoniae. In contrast, in mouse models of infection the ΔlivHMGF and the IDM mutant strain with a disrupted copy of livH were both significantly outcompeted by the wild-type strain. These data suggest that there is an important role for the S. pneumoniae BCAA specifically during in vivo growth, a conclusion that is supported by previous publications which have shown that disruption of BCAA synthesis affects the virulence of the unrelated pathogens B. pseudomallei and M. bovis (3, 24). However, the effect of loss of LivHMGF on virulence was only detectable in competitive infection experiments, and after i.n. inoculation with either the ΔlivHMGF or wild-type strain, bacterial CFU in target organs and progression of infection were similar. When transferred to the TIGR4 strain, the ΔlivHMGF deletion affected virulence in the pneumonia model but not in the model of systemic infection, a surprising result given that the effect on virulence was most marked in the systemic model for the serotype 3 strain. These data have no immediately apparent explanation and provide further evidence that the effect of mutations of S. pneumoniae genes depends on strain background. Overall, the data suggest that LivJHMGF does not have a powerful effect on S. pneumoniae disease pathogenesis, perhaps because the S. pneumoniae genome contains genes encoding enzymes required for BCAA synthesis (Sp0445-50) (24, 40). These may partially compensate for impaired BCAA uptake in vivo, perhaps to a variable degree between strains, so the effects of the ΔlivHMGF mutation on in vivo growth are only detectable if competing against a wild-type strain and depend on strain background. Exactly why the loss of BCAA affects virulence is not clear. The most obvious explanation is a nutritional requirement for BCAA in vivo, and the differences in CI between sites could be explained by variations in bacterial demand for BCAA, perhaps related to differences in bacterial replication rate in combination with host physiology. However, there was a marked difference in CI between growth in blood and during infection for the ΔSp0750 mutant strain, whereas other mutant strains with reduced CIs in blood only had weakly reduced CIs during infection. These data perhaps indicate that the loss of virulence associated with mutation of LivJHMGF may be more complex than simple impaired growth under physiological conditions. The impaired CI of the ΔlivHMGF strain compared to the wild-type strain when cultured in blood was not improved by the addition of exogenous BCAAs. This would be the expected result if LivJHMGF is a BCAA ABC transporter and there are no alternative S. pneumoniae low-affinity BCAA transporter systems that could compensate for a BCAA transport defect when BCAAs are present in high concentrations in the environment. Genes from both the livJHMGF and the Sp0445-50 operons have increased expression in cerebrospinal fluid in a rabbit model of meningitis (28) and are under the negative control of the transcriptional regulator CodY (16), but the relationship between CodY repression, in vitro and in vivo expression of livJHMGF, and BCAA transport requires further investigation.

To conclude, we have investigated whether a range of S. pneumoniae ABC transporters affect virulence and identified that six of the nine investigated had some effect on the pathogenesis of infection compared to the wild-type strain using competitive infection experiments. The effects on virulence were generally weak, probably due to redundancy compensating for loss of function of individual ABC transporters. The functions of the majority of the ABC transporters affecting virulence were not clear, but we have characterized one encoded by livJHMGF in more detail and confirmed that it encodes a BCAA ABC transporter. Further investigation is required to identify the substrates of the remaining ABC transporters and to define why BCAA uptake is important for S. pneumoniae virulence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the British Lung Foundation (grant P02/3) and the Wellcome Trust (grant 076442).

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. D., L. M. Wagner, T. J. Graddis, R. Landick, T. K. Antonucci, A. L. Gibson, and D. L. Oxender. 1990. Nucleotide sequence and genetic characterization reveal six essential genes for the LIV-I and LS transport systems of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 26511436-11443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderton, J. M., G. Rajam, S. Romero-Steiner, S. Summer, A. P. Kowalczyk, G. M. Carlone, J. S. Sampson, and E. W. Ades. 2007. E-cadherin is a receptor for the common protein pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 42225-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkins, T., R. G. Prior, K. Mack, P. Russell, M. Nelson, P. C. Oyston, G. Dougan, and R. W. Titball. 2002. A mutant of Burkholderia pseudomallei, auxotrophic in the branched chain amino acid biosynthetic pathway, is attenuated and protective in a murine model of melioidosis. Infect. Immun. 705290-5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmann, S., and S. Hammerschmidt. 2006. Versatility of pneumococcal surface proteins. Microbiology 152295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuzon, C. R., and D. W. Holden. 2001. Use of mixed infections with Salmonella strains to study virulence genes and their interactions in vivo. Microbes Infect. 31345-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, J. S., S. M. Gilliland, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenicity island encoding an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40572-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, J. S., S. M. Gilliland, J. Ruiz-Albert, and D. W. Holden. 2002. Characterization of pit, a Streptococcus pneumoniae iron uptake ABC transporter. Infect. Immun. 704389-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, J. S., T. Hussell, S. M. Gilliland, D. W. Holden, J. C. Paton, M. R. Ehrenstein, M. J. Walport, and M. Botto. 2002. The classical pathway is the dominant complement pathway required for innate immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9916969-16974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darwin, A. J. 2005. Genome-wide screens to identify genes of human pathogenic Yersinia species that are expressed during host infection. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 7135-149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darwin, A. J., and V. L. Miller. 1999. Identification of Yersinia enterocolitica genes affecting survival in an animal host using signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 3251-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson, A. L., E. Dassa, C. Orelle, and J. Chen. 2008. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72317-364, table. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garmory, H. S., and R. W. Titball. 2004. ATP-binding cassette transporters are targets for the development of antibacterial vaccines and therapies. Infect. Immun. 726757-6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harland, D. N., H. S. Garmory, K. A. Brown, and R. W. Titball. 2005. An association between ATP binding cassette systems, genome sizes and lifestyles of bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 156434-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison, L. I., H. N. Christensen, M. E. Handlogten, D. L. Oxender, and S. C. Quay. 1975. Transport of l-4-azaleucine in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 122957-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hava, D. L., and A. Camilli. 2002. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol. Microbiol. 451389-1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendriksen, W. T., H. J. Bootsma, S. Estevao, T. Hoogenboezem, A. de Jong, R. de Groot, O. P. Kuipers, and P. W. Hermans. 2008. CodY of Streptococcus pneumoniae: link between nutritional gene regulation and colonization. J. Bacteriol. 190590-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins, C. F. 2001. ABC transporters: physiology, structure and mechanism-an overview. Res. Microbiol. 152205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoshino, T., K. Kose-Terai, and K. Sato. 1992. Solubilization and reconstitution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-affinity branched-chain amino acid transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 26721313-21318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosie, A. H., and P. S. Poole. 2001. Bacterial ABC transporters of amino acids. Res. Microbiol. 152259-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston, J. W., L. E. Myers, M. M. Ochs, W. H. Benjamin, Jr., D. E. Briles, and S. K. Hollingshead. 2004. Lipoprotein PsaA in virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: surface accessibility and role in protection from superoxide. Infect. Immun. 725858-5867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khandavilli, S., K. A. Homer, J. Yuste, S. Basavanna, T. Mitchell, and J. S. Brown. 2008. Maturation of Streptococcus pneumoniae lipoproteins by a type II signal peptidase is required for ABC transporter function and full virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 67541-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau, G. W., S. Haataja, M. Lonetto, S. E. Kensit, A. Marra, A. P. Bryant, D. McDevitt, D. A. Morrison, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A functional genomic analysis of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40555-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei, B., M. Liu, G. L. Chesney, and J. M. Musser. 2004. Identification of new candidate vaccine antigens made by Streptococcus pyogenes: purification and characterization of 16 putative extracellular lipoproteins. J. Infect. Dis. 18979-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAdam, R. A., T. R. Weisbrod, J. Martin, J. D. Scuderi, A. M. Brown, J. D. Cirillo, B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1995. In vivo growth characteristics of leucine and methionine auxotrophic mutants of Mycobacterium bovis BCG generated by transposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 631004-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAllister, L. J., H. J. Tseng, A. D. Ogunniyi, M. P. Jennings, A. G. McEwan, and J. C. Paton. 2004. Molecular analysis of the psa permease complex of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 53889-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mei, J. M., F. Nourbakhsh, C. W. Ford, and D. W. Holden. 1997. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes in a murine model of bacteraemia using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 26399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyaji, E. N., W. O. Dias, M. Gamberini, V. C. Gebara, R. P. Schenkman, J. Wild, P. Riedl, J. Reimann, R. Schirmbeck, and L. C. Leite. 2001. PsaA (pneumococcal surface adhesin A) and PspA (pneumococcal surface protein A) DNA vaccines induce humoral and cellular immune responses against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine 20805-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orihuela, C. J., J. N. Radin, J. E. Sublett, G. Gao, D. Kaushal, and E. I. Tuomanen. 2004. Microarray analysis of pneumococcal gene expression during invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 725582-5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit, C. M., J. R. Brown, K. Ingraham, A. P. Bryant, and D. J. Holmes. 2001. Lipid modification of prelipoproteins is dispensable for growth in vitro but essential for virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren, Q., and I. T. Paulsen. 2007. Large-scale comparative genomic analyses of cytoplasmic membrane transport systems in prokaryotes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12165-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richarme, G., and A. Kepes. 1983. Study of binding protein-ligand interaction by ammonium sulfate-assisted adsorption on cellulose esters filters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 74216-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saier, M. H., Jr. 2000. A functional-phylogenetic classification system for transmembrane solute transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64354-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and Maniatis, T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory cloning, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY.

- 34.Seo, J. Y., S. Y. Seong, B. Y. Ahn, I. C. Kwon, H. Chung, and S. Y. Jeong. 2002. Cross-protective immunity of mice induced by oral immunization with pneumococcal surface adhesin a encapsulated in microspheres. Infect. Immun. 701143-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Severi, E., G. Randle, P. Kivlin, K. Whitfield, R. Young, R. Moxon, D. Kelly, D. Hood, and G. H. Thomas. 2005. Sialic acid transport in Haemophilus influenzae is essential for lipopolysaccharide sialylation and serum resistance and is dependent on a novel tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 581173-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shevchuk, N. A., A. V. Bryksin, Y. A. Nusinovich, F. C. Cabello, M. Sutherland, and S. Ladisch. 2004. Construction of long DNA molecules using long PCR-based fusion of several fragments simultaneously. Nucleic Acids Res. 32e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperandio, B., C. Gautier, S. McGovern, D. S. Ehrlich, P. Renault, I. Martin-Verstraete, and E. Guedon. 2007. Control of methionine synthesis and uptake by MetR and homocysteine in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 1897032-7044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Speziali, C. D., S. E. Dale, J. A. Henderson, E. D. Vines, and D. E. Heinrichs. 2006. Requirement of Staphylococcus aureus ATP-binding cassette-ATPase FhuC for iron-restricted growth and evidence that it functions with more than one iron transporter. J. Bacteriol. 1882048-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutcliffe, I. C., and R. R. Russell. 1995. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1771123-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas, G. H., T. Southworth, M. R. Leon-Kempis, A. Leech, and D. J. Kelly. 2006. Novel ligands for the extracellular solute receptors of two bacterial TRAP transporters. Microbiology 152187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomaz, A. 1964. Studies on the competence (for genetic transformation) of Diplococcus pneumoniae in a synthetic medium, abstr. G87. Abstr. 64th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 43.Tseng, H. J., A. G. McEwan, J. C. Paton, and M. P. Jennings. 2002. Virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: PsaA mutants are hypersensitive to oxidative stress. Infect. Immun. 701635-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware, D., Y. Jiang, W. Lin, and E. Swiatlo. 2006. Involvement of potD in Streptococcus pneumoniae polyamine transport and pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 74352-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webb, A. J., K. A. Homer, and A. H. Hosie. 2008. Two closely related ABC transporters in Streptococcus mutans are involved in disaccharide and/or oligosaccharide uptake. J. Bacteriol. 190168-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]