Abstract

The gene designated BAB1_1460 in the Brucella abortus 2308 genome sequence is predicted to encode the manganese transporter MntH. Phenotypic analysis of an isogenic mntH mutant indicates that MntH is the sole high-affinity manganese transporter in this bacterium but that MntH does not play a detectable role in the transport of Fe2+, Zn2+, Co2+, or Ni2+. Consistent with the apparent selectivity of the corresponding gene product, the expression of the mntH gene in B. abortus 2308 is repressed by Mn2+, but not Fe2+, and this Mn-responsive expression is mediated by a Mur-like repressor. The B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 exhibits increased susceptibility to oxidative killing in vitro compared to strain 2308, and a comparative analysis of the superoxide dismutase activities present in these two strains indicates that the parental strain requires MntH in order to make wild-type levels of its manganese superoxide dismutase SodA. The B. abortus mntH mutant also exhibits extreme attenuation in both cultured murine macrophages and experimentally infected C57BL/6 mice. These experimental findings indicate that Mn2+ transport mediated by MntH plays an important role in the physiology of B. abortus 2308, particularly during its intracellular survival and replication in the host.

Brucella abortus is a gram-negative bacterium that is responsible for the zoonotic disease brucellosis. Brucellosis causes spontaneous abortion and sterility in ruminants (27) and a debilitating febrile illness in humans known as undulant fever (17). The ability of brucellae to cause disease is directly related to their capacity to establish and maintain intracellular infection in host macrophages (63). Within the phagosomal compartment in these host cells, brucellae must cope with oxidative stress, low pH, and nutrient deprivation. The availability of metal ions is restricted within this environment due in part to the activity of the host natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (NRAMP-1), which transports divalent cations out of the phagosome (40). Mn2+ serves as an important cofactor for a variety of bacterial enzymes, including those involved in carbon metabolism, induction of the stringent response, and detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (55). Consequently, the inability of brucellae to acquire sufficient levels of this divalent cation may compromise their ability to successfully adapt to the environmental conditions encountered during residence in their intracellular niche.

Manganese uptake by bacteria is typically accomplished through the activity of either ABC-type transporters such as the SitABC complex (4, 42, 59, 65) or H+-dependent manganese transporters such as MntH (37, 41, 52, 60). Many bacteria possess both types of Mn2+ transporters (55), but a survey of the publicly available Brucella genome sequences (14, 20, 36, 57) suggests that these bacteria do not produce a SitABC-type transporter and rely solely on an MntH homolog for the high-affinity transport of Mn2+. Escherichia coli MntH was originally described as being able to transport both Mn2+ and Fe2+ (52), but subsequent studies indicated that this and other bacterial MntH proteins are highly selective Mn2+ transporters that play a minor, if any, role in Fe2+ transport under physiologically relevant conditions (41). To examine the role of Brucella MntH in Mn2+ transport and virulence, the gene annotated as BAB1_1460 in the B. abortus 2308 genome sequence was disrupted in this strain by gene replacement and the phenotype of the resulting mutant (MWV15) was examined. The results of these studies indicate that MntH plays a critical role in Mn2+ transport in B. abortus 2308 and that the presence of this manganese transporter is essential for the wild-type resistance of this strain to oxidative killing in vitro and its virulence in the mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Brucella abortus 2308 and derivatives of this strain were cultivated on Schaedler agar supplemented with 5% defibrinated bovine blood (SBA) at 37°C with 5% CO2 or in brucella broth at 37°C with shaking unless otherwise noted. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used as the host strain for recombinant DNA procedures, and this strain was cultivated on tryptic soy agar at 37°C or in LB broth at 37°C with shaking. Growth media were supplemented with ampicillin (25 μg/ml for B. abortus and 100 μg/ml for E. coli DH5α), chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml for B. abortus and 30 μg/ml for E. coli DH5α), and/or kanamycin (45 μg/ml) as necessary. Brucella stock cultures were maintained in brucella broth supplemented with 25% glycerol, and E. coli stock cultures were maintained in LB supplemented with 25% glycerol at −80°C.

Construction of an mntH-lacZ transcriptional fusion.

Oligonucleotide primers (forward, 5′-GAGCGGGCCATCCTTCTGAA-3′; reverse, 5′-GTTGCCGGGATCCATATAACC-3′) and PCR were used to amplify a 1,031-bp fragment of genomic DNA from B. abortus 2308 containing portions of the mraW (BAB1_1458) and mntH (BAB1_1460) genes and intervening regions. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with HindIII and KpnI, and a 239-bp HindIII/KpnI fragment containing upstream sequences and extending 8 bp into the mntH coding region was directionally cloned into the lacZ transcriptional fusion vector pMR15 (32). The authenticity of the mntH-lacZ fusion in the resulting plasmid, pEAM1, was verified by restriction mapping and nucleotide sequence analysis. Transcriptional activity of the β-galactosidase reporter fusion was determined using the methods described by Miller (53).

Construction of the B. abortus mur mutant Fur2.

Plasmid pDS1 contains an 867-bp fragment of genomic DNA from B. abortus 2308 containing the mur homolog designated BAB1_1668 cloned into pUC9 (5). An inverse PCR strategy (23) was used to generate a linear derivative of pDS1 that lacks a 338-bp region internal to the 426-bp coding region of Brucella mur by using the primers Δfur1 (5′-GCCTCAGCTCCTGCTCATAAT-3′) and Δfur2 (CATCACCGGCTTGAACTTTA-3′). The chloramphenicol resistance gene from pBC-SK (NEB) was ligated to the linear Δmur derivative of pDS1, and the resulting plasmid was used to introduce a mur mutation into the genome of B. abortus 2308 by gene replacement using the methods described by Elzer et al. (25). The genotype of the B. abortus mur mutant (Fur2) constructed in this fashion was confirmed by Southern blot analysis with cat- and mur-specific probes (5).

Construction and genetic complementation of the B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15.

A 1,566-bp region encompassing the putative mntH gene (BAB1_1460) (forward primer, 5′-TTCCCCTATTCCCTTAACAT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GATCGGCGTTCTATTTCTTT-3′) was amplified from B. abortus 2308 genomic DNA by PCR using Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). The resulting plasmid was digested with BamHI and HindIII to remove a 696-bp region internal to the predicted mntH coding region, treated with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and ligated with a 987-bp SmaI/HincII fragment containing the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene from pBlueCM2 (61). This plasmid was then used to construct an mntH mutant from B. abortus 2308 via gene replacement using previously described procedures (25). The genotype of the B. abortus mntH mutant (designated MWV15) was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA from this strain with mntH-, cat-, and pGEM-T Easy-specific primer sets.

For genetic complementation of the mntH mutation in MWV15, a 1,595-bp DNA fragment containing the mntH coding region was amplified by PCR (forward primer, 5′-AACATACTCCCCCTACTCCCTTATTC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GTATCAGATCGGCGTTCTATTTCTT-3′) from B. abortus 2308 genomic DNA by using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy after A-tagging of the PCR fragments according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The cloned DNA fragment was then excised from this plasmid as an ApaI/SacI fragment and cloned into the corresponding restriction sites in pMR10 (30). This mntH-containing plasmid, pEA31, was introduced into B. abortus MWV15 by electroporation, and the resulting strain was given the designation MWV15.C.

Capacity of MnCl2 to stimulate the growth of B. abortus strains in the presence of EDDA.

B. abortus strains were grown on SBA for 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 and harvested into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The optical density of the bacterial cell suspensions at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.15 (109 CFU/ml); 100 μl of each cell suspension was mixed with 3 ml of tryptic soy broth containing 0.7% agar and spread evenly over the surface of tryptic soy broth solidified with 1.5% agar containing 300 μM ethylenediamediacetic acid (EDDA) in 100- by 15-mm petri plates. A 7-mm-diameter Whatman filter paper disk was placed in the center of each plate and impregnated with 10 μl of a solution containing 7.95 μM, 79.5 μM, 795 μM, or 7.95 mM MnCl2. After 72 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the diameter of the zone of bacterial growth surrounding each disk was measured to the nearest millimeter. The diameters of the zones of growth from five separate plates were measured for each bacterial strain examined.

Growth of B. abortus strains in manganese- and iron-restricted media.

Low-manganese minimal medium was prepared using a modification of the protocols originally described by López-Goñi et al. (50). Briefly, a minimal medium based on Gerhardt's minimal medium (31) but supplemented with 0.5 g/liter yeast extract was treated twice with the chelator 8-hydroxyquinolone. After each treatment, the metal-chelate complexes were removed by chloroform extraction and the residual chloroform was removed from the medium by flash evaporation. Following chelator treatment, 50 μM FeCl3 and 50 μM MgCl2 (final concentrations) were added to the culture medium to ensure iron- and magnesium-replete growth conditions. Analysis of representative samples of this medium by atomic absorption spectrophotometry indicates that it contains <3 μM manganese. Low-iron minimal medium was prepared in the same manner, with the exception that following treatment with 8-hydroxyquinolone, 50 μM MgCl2 and 50 μM MnCl2 were added to the medium. Analysis of representative samples of the low-iron minimal medium prepared in this manner indicates that it contains <3 μM iron.

B. abortus strains were grown on SBA at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 72 h and harvested into the low-manganese minimal medium, and the optical density of the cell suspensions at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.15 (109 CFU/ml). One hundred microliters of each suspension was used to inoculate 100 ml of low-manganese medium or low-manganese medium supplemented with 1, 5, 10, or 50 μM MnCl2, 5 μM CoCl2·6H2O, 20 μM NiCl2·6H2O, or 100 μM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, ZnCl2, or CuCl2. Brucella strains grown as described above were also harvested and inoculated into low-iron minimal medium at a cell density of 106 CFU/ml. Bacterial cultures were incubated at 37°C in 500-ml flasks with shaking at 175 rpm. Bacterial growth in these cultures was evaluated by serial dilution and plating on SBA, followed by incubation of the SBA plates at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Resistance of B. abortus strains to H2O2 and the superoxide generators paraquat and menadione in disk sensitivity assays.

Brucella abortus 2308, MWV15, and MWV15.C were grown to mid-log phase in brucella broth, and the cultures were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.15 (approximately 109 CFU/ml). One hundred microliters of each cell suspension was mixed with 3 ml of tryptic soy broth containing 0.7% agar and spread evenly over the surface of either a tryptic soy agar plate (for the H2O2 sensitivity assays) or a tryptic soy agar plate supplemented with 1,000 U/ml of bovine liver catalase (Sigma) (for the assays measuring sensitivity to the superoxide generators paraquat and menadione). A 7-mm-diameter Whatman filter paper disk was placed in the center of each plate and impregnated with 10 μl of one of the following solutions: 30% H2O2, 0.5 M paraquat, or 10 mM menadione. After 72 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the diameter of the zone of inhibition surrounding each disk on the plates was measured to the nearest millimeter. The diameters of the zones of inhibition from five separate plates were measured for each bacterial strain examined.

Determination of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in Brucella strains.

Brucella strains were grown to mid-log phase in brucella broth. Twenty-five-milliliter samples from each culture were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and resuspended in 2 ml native gel buffer (40 mM glycine, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.9]). The cell suspensions were transferred to 2-ml screw-cap polypropylene tubes (catalog no. 72.693; Sarstedt) containing 1 g of 0.1 mM zirconia beads, and the cells were disrupted by subjecting them to 6- to 40-s cycles at 6 m/s in a Savant FastPrep 120 bead beater (Bio 101), with 1 min on ice between each cycle. Cellular debris was harvested by centrifugation at 4°C for 20 min at 10,000 × g. The cleared supernatant was removed and the protein concentration determined using the Bradford assay (9). Fifteen micrograms of each supernatant was loaded onto a 12% native acrylamide gel and subjected to electrophoresis for 1.5 h at 75 mA. Superoxide activity in the gels was determined using previously described methods (47). Briefly, the gel was soaked in 50 ml of solution 1 (50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.5], 28 mM N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine, 0.028 mM riboflavin) for 10 min in the dark with gentle rocking. Solution 1 was poured off, 50 ml of solution 2 (50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.5], 2.5 mM nitroblue tetrazolium) was added, and the gel was allowed to gently rock in this solution for 10 min in the dark. Solution 2 was then poured off, and the gel was exposed to a bench lamp for 15 min. Color development in the gel was stopped by the addition of a 7% solution of acetic acid, and a flatbed scanner was used to capture images of the gels.

Infection of cultured murine resident peritoneal macrophages.

Following euthanasia, macrophages were harvested from the peritoneal cavities of 9-week-old C57BL/6 mice by lavage with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)-5% fetal calf serum (FCS) by using previously described procedures (26). Pooled macrophages in 200 μl of DMEM-5% FCS were cultivated in 96-well plates at a concentration of 1.6 × 105 per well at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cell cultures were enriched for macrophages by washing away nonadherent cells after overnight incubation. B. abortus cells were opsonized for 30 min with a subagglutinating dilution (1:2,000) of hyperimmune C57BL/6 mouse serum in DMEM-5% FCS. Opsonized bacteria were added to macrophages at a ratio of approximately 100 brucellae per macrophage, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h to allow time for phagocytosis. The culture medium was then replaced with 200 μl of DMEM-5% FCS containing 50 μg/ml gentamicin and incubated for 1 h to kill extracellular brucellae. Macrophages were then washed three times with warm PBS-5% FCS and maintained in DMEM-5% FCS containing 12.5 μg/ml gentamicin for the remainder of the experiment. At 2, 24, and 48 h after infection, the macrophages were lysed with 0.1% deoxycholate and the number of intracellular brucellae was determined by serial dilution of the lysates in PBS and plating on SBA, followed by incubation of the SBA plates at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Experimental infection of C57BL/6 mice.

Six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were infected via the peritoneal route with 5 × 104 CFU of B. abortus 2308, MWV15 (2308 ΔmntH), or MWV15.C [MWV15(pEA31)], and the spleen colonization profiles of these strains in the mice were determined using previously described methods (30).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using the two-tailed Student t test (64). P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

BAB1_1460 is predicted to encode an MntH homolog, and the corresponding gene exhibits Mn-responsive repression in B. abortus 2308.

The gene designated BAB1_1460 in the B. abortus 2308 genome sequence is predicted to encode a 456-amino-acid protein that shares 35.9% identity with the Escherichia coli manganese transporter MntH (52). Analysis of the amino acid sequence of the putative Brucella MntH homolog with the TMpred algorithm (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) predicts that this protein, like its E. coli counterpart, is an integral membrane protein with multiple membrane-spanning regions. All eight of the amino acid residues (Asp34, Asn37, Glu102, Asp109, Glu112, His211, Asp238, and Asn401) that have been shown by site-directed mutagenesis to be critical for Mn2+ transport by E. coli MntH (15, 35) are conserved in Brucella MntH. Based on the annotation of the B. abortus 2308 genome sequence (14), the Brucella mntH homolog is located downstream of a gene (BAB1_1459) encoding a hypothetical protein. Whether or not BAB1_1459 is expressed, or mntH is cotranscribed in an operon with this gene, has not been experimentally determined.

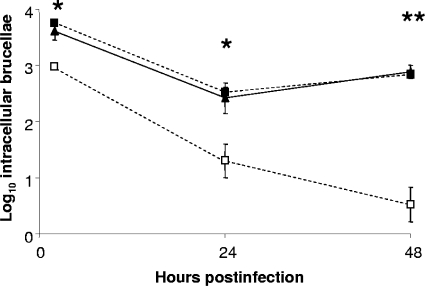

A bioinformatics-based study described by Rodionov et al. (62) predicts the presence of a “Mur” box upstream of the Brucella melitensis mntH homolog BMEI0569. This conserved sequence (AATGCAAATAGTTTGCAAC) is also centered 35 nucleotides upstream of the putative mntH coding region (BAB1_1460) in the B. abortus 2308 genome sequence. Mur is a structural homolog of the ferric uptake regulator Fur, which controls the expression of manganese transport genes in Rhizobium leguminosarum (21) and Sinorhizobium meliloti (16), two alphaproteobacteria that are close phylogenetic relatives of Brucella spp., in a manganese-responsive manner. As shown in Fig. 1A, the level of β-galactosidase production from an mntH-lacZ fusion in B. abortus 2308 during growth in a nutritionally complete growth medium (brucella broth) suggests that mntH exhibits a considerable degree of basal expression in this bacterium even when sufficient levels of Mn2+ are present. The addition of increasing amounts of MnCl2 to the culture medium ranging from 50 μM to 1 mM represses β-galactosidase production in B. abortus 2308 (Fig. 1A) but not in the isogenic mur mutant Fur2 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the addition of up to 500 μM FeCl3 fails to repress the expression of the mntH-lacZ fusion in either B. abortus 2308 or the mur mutant (Fig. 1B). This pattern of manganese-responsive expression is consistent with the proposed function of MntH and further indicates that Mur plays an active role in regulating the expression of the corresponding gene.

FIG. 1.

Manganese-responsive repression of an mntH-lacZ transcriptional fusion in B. abortus 2308 is mediated by Mur. (A) Expression of an mntH-lacZ fusion in B. abortus 2308 following 24 h of growth in brucella broth or brucella broth supplemented with 50, 250, or 500 μM MnCl2. (B) Activity of the mntH-lacZ fusion in B. abortus 2308 and the isogenic mur mutant (Fur2) following 24 h of growth in unsupplemented brucella broth (white bars), brucella broth supplemented with 500 μM MnCl2 (hatched bars), or brucella broth supplemented with 500 μM FeCl2 (black bars). β-Galactosidase activity is presented on the y axis in Miller units (53). The data presented are means and standard deviations for triplicate determinations from a single culture in a single experiment. The data presented are representative of multiple (≥3) experiments from which equivalent results and statistical trends were obtained. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (for comparisons of β-galactosidase activities in unsupplemented medium and medium supplemented with MnCl2 or FeCl3).

The B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 exhibits a manganese-selective defect in metal acquisition in vitro.

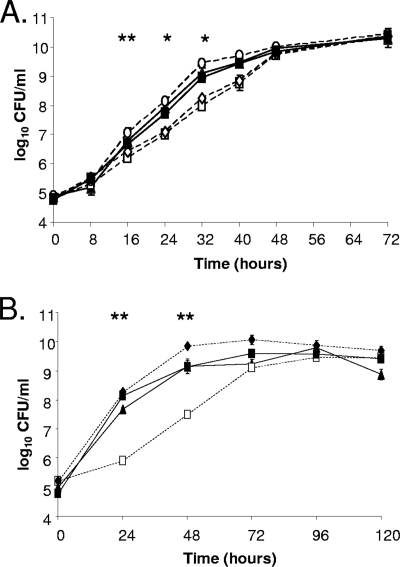

The B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 exhibits slower growth in brucella broth, a complex growth medium, than does the parental 2308 strain or a derivative of MWV15 carrying a plasmid-borne copy of mntH (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the predicted function of Brucella MntH as a manganese transporter, supplementation of brucella broth with 50 μM MnCl2 allows MWV15 to grow with the same vigor in brucella broth as does strain 2308. Supplementation of this medium with 50 μM FeCl2, in contrast, will not rescue the growth defect exhibited by MWV15 in brucella broth (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Supplemental MnCl2 restores wild-type growth of the B. abortus mntH mutant in broth culture. (A) Growth of B. abortus 2308 (▴), MWV15 (2308 mntH) (□), and MWV15.C [MWV15(pEA31)] (▪) in brucella broth and MWV15 in brucella broth supplemented with 50 μM MnCl2 (⧫) or 50 μM FeCl2 (⋄). (B) Growth of B. abortus 2308 (▴), MWV15 (□), and MWV15.C (▪) in low-manganese minimal medium and MWV15 in low-manganese medium supplemented with 50 μM MnCl2 (⧫). The data presented are the means and standard deviations for triplicate determinations from a single flask for each strain at each experimental time point in a single experiment. The data are representative of multiple (≥3) experiments from which equivalent results and statistical trends were obtained. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (for comparisons of strain 2308 with MWV15 or MWV15.C).

The B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 also displays a significantly reduced ability to use MnCl2 as a manganese source compared to the parental 2308 strain on a solid growth medium containing the chelator EDDA (Table 1). Good growth is observed for the parental 2308 strain surrounding disks containing 79.5 μM MnCl2, but a comparable level of growth is observed for the mntH mutant only around disks containing 7.95 mM MnCl2 in this assay. EDDA has an approximately 100-fold-greater affinity for Fe2+ (equilibrium constant = 6.45 × 109) than it does for Mn2+ (5.13 × 107) (13). Because of its high affinity for iron, EDDA is often the chelator of choice for in vitro experiments designed to detect defects in iron acquisition in bacterial mutants (18). Thus, it is notable that although the B. abortus mntH mutant exhibits a reduced zone of growth around disks containing FeCl3 or Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 on plates containing the same concentration of EDDA compared to strain 2308, this reduction in zone size cannot be rescued by adding increasing amounts of either iron source to the disks (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Capacity of B. abortus 2308, MWV15, and MWV15.C to use MnCl2 as a manganese source

| Strain | Growth (mm) around disk containinga:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 79.5 μM MnCl2 | 795 μM MnCl2 | 7.95 mM MnCl2 | |

| 2308 | 43.1 ± 0.6 | 52.3 ± 1 | 67.3 ± 0.6 |

| MWV15 | NGb | NG | 42.8 ± 1.4*** |

| MWV15.C | 43.4 ± 1.8 | 52.7 ± 0.3 | 69 ± 3.2 |

The diameters of the zones of bacterial growth on a solid growth medium supplemented with 300 μM EDDA around filter disks impregnated with 10 μl of a 10-μg/ml, 100-μg/ml, or 1-mg/ml solution of MnCl2 were measured after 72 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. The values presented are the means ± standard deviations of the zone sizes obtained from three separate experiments, and three separate determinations of growth were obtained for each strain in each experiment. ***, P ≤ 0.005 (for comparisons of MWV15 with 2308 and MWV15.C).

NG, no growth. No zone of growth was observed surrounding the disks impregnated with 10 or 100 μg/ml MnCl2 for B. abortus MWV15.

Also consistent with its predicted function, the B. abortus mntH mutant exhibits delayed growth compared to 2308 when these strains are cultivated in a low-manganese minimal medium in broth culture (Fig. 2B). The addition of 50 μM MnCl2 restores wild-type growth of the mntH mutant in this medium. In contrast, the B. abortus mntH mutant exhibits the same growth profile in low-iron minimal medium as the parental 2308 strain (data not shown).

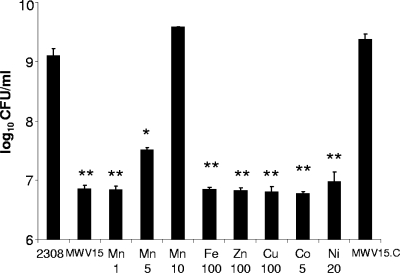

To further examine the selectivity of the metal acquisition defect exhibited by B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15, the capacity of increasing concentrations of MnCl2 or other metals that have been reported to be transported by MntH homologs (e.g., Fe2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, and Ni2+) to alleviate the growth restriction exhibited by this strain in low-manganese medium was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 3, only MnCl2 at a concentration of 10 μM was able to restore wild-type growth of the B. abortus mntH mutant in this medium. CoCl2 and NiCl2 were used at lower levels than the other divalent cation sources in these experiments because Co2+ and Ni2+ both inhibit the growth of B. abortus 2308 and MWV15 equally when used at higher concentrations.

FIG. 3.

Growth of the B. abortus mntH mutant in low-manganese medium supplemented with Mn2+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Cu2+. Bacterial cell cultures were inoculated into low-manganese medium at cell densities of approximately 105 CFU/ml, and the number of bacteria present in these cultures following 48 h of incubation was enumerated by serial dilution and plating. Shown are the B. abortus parental strain (2308), the mntH mutant (MWV15), and the mntH mutant grown in low-manganese minimal medium supplemented with MnCl2 at concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 μM (designated Mn1, Mn5, and Mn10, respectively). MWV15 cultures supplemented with 100 μM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 (Fe 100), 100 μM ZnCl2 (Zn 100), 5 μM CoCl2·6H2O (Co 5), and 20 μM NiCl2·6H2O (Ni 20) are shown as well. Growth of the B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 carrying a plasmid-borne copy of mntH (MWV15.C) in low-manganese minimal medium is also shown. The data presented are the means and standard deviations for triplicate determinations from single flasks for each strain and experimental condition in a single experiment. The data are representative of multiple (≥3) experiments from which equivalent results and statistical trends were obtained. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (for comparisons of strain 2308 with MWV15 or MVW15.C).

Genetic complementation of B. abortus MWV15 with a plasmid-borne copy of the parental mntH gene restored the ability of this strain to use MnCl2 as a manganese source on the EDDA-containing plates with the same efficiency as the parental 2308 strain (Table 1) and restored its ability to replicate with the same growth kinetics as 2308 in the low-manganese minimal medium (Fig. 2A).

The B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 displays reduced Mn SOD activity compared to the parental 2308 strain.

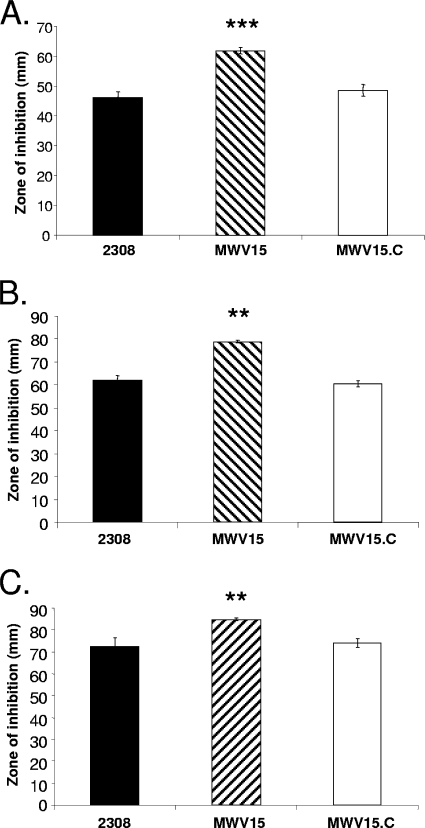

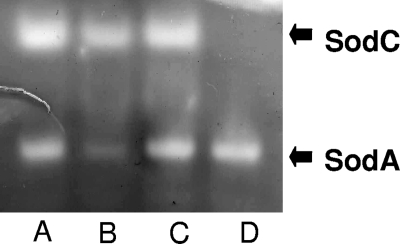

The presence of MntH is required for wild-type resistance of B. abortus 2308 to oxidative killing in in vitro assays. The parental 2308 strain is considerably more resistant to killing by both H2O2 (Fig. 4A) and O2− generated by the redox cyclers paraquat (Fig. 4B) and menadione (Fig. 4C) in disk sensitivity assays than the mntH mutant, and the introduction of a plasmid-borne copy of mntH into the mutant restores wild-type levels of resistance to H2O2, paraquat, and menadione in these assays (Fig. 4A to C). In most bacteria that have been studied, there is a strong link between the ability to acquire Mn2+ and resistance to oxidative stress (39). B. abortus 2308 produces a manganese-containing SOD (SodA) (68), and phenotypic analysis of a B. abortus sodA mutant indicates that SodA is an important antioxidant in this bacterium (29). Consequently, it is possible that the B. abortus mntH mutant is unable to transport sufficient Mn2+ to produce wild-type levels of Mn SOD activity. The results shown in Fig. 5 support this proposition. Equivalent levels of Cu/Zn SOD activity are observed in native gels for cell lysates from B. abortus 2308 and MWV15, but the mntH mutant displays a greatly reduced level of Mn SOD activity compared to the parental 2308 strain. MWV15 carrying a plasmid-borne copy of the mntH gene, on the other hand, displays the same level of Mn SOD activity as 2308. The basis for the increased sensitivity of the B. abortus mntH mutant to H2O2 is unknown, but hypersensitivity to H2O2 has been previously reported for other bacterial strains that are deficient in SOD activity (11).

FIG. 4.

Resistance of B. abortus 2308, MWV15 (2308 mntH), and MWV15.C [MWV15(pEA31)] to H2O2 (A), paraquat (B), and menadione (C) in disk sensitivity assays. The data presented are zones of inhibition around disks containing H2O2 (A), paraquat (B), or menadione (C). The values are the means ± standard deviations of the zone sizes obtained from three separate experiments, and three separate determinations of growth were obtained for each strain in each experiment. **, P ≤ 0.005; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (for comparisons of MWV15 with strain 2308 or MWV15.C).

FIG. 5.

SOD activity in B. abortus 2308, MWV15, and MWV15C. Cu/Zn SOD (SodC) (cyanide-sensitive) and Mn SOD (SodA) (cyanide- and H2O2-resistant) activities, detected in the parental 2308 strain (lane A), the mntH mutant MWV15 (lane B), and a derivative of MWV15 carrying a plasmid-borne copy of mntH (lane C). The B. abortus sodC mutant MEK2 (26) was included as a control (lane D). The gel presented is representative of multiple experiments (≥3) in which equivalent results were observed.

MntH is required for wild-type virulence of B. abortus 2308 in the C57BL/6 mouse model.

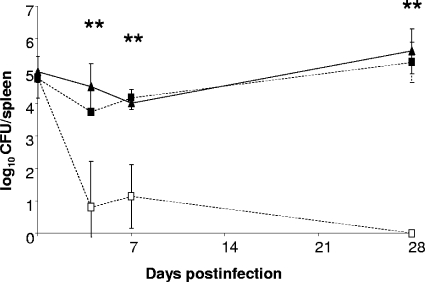

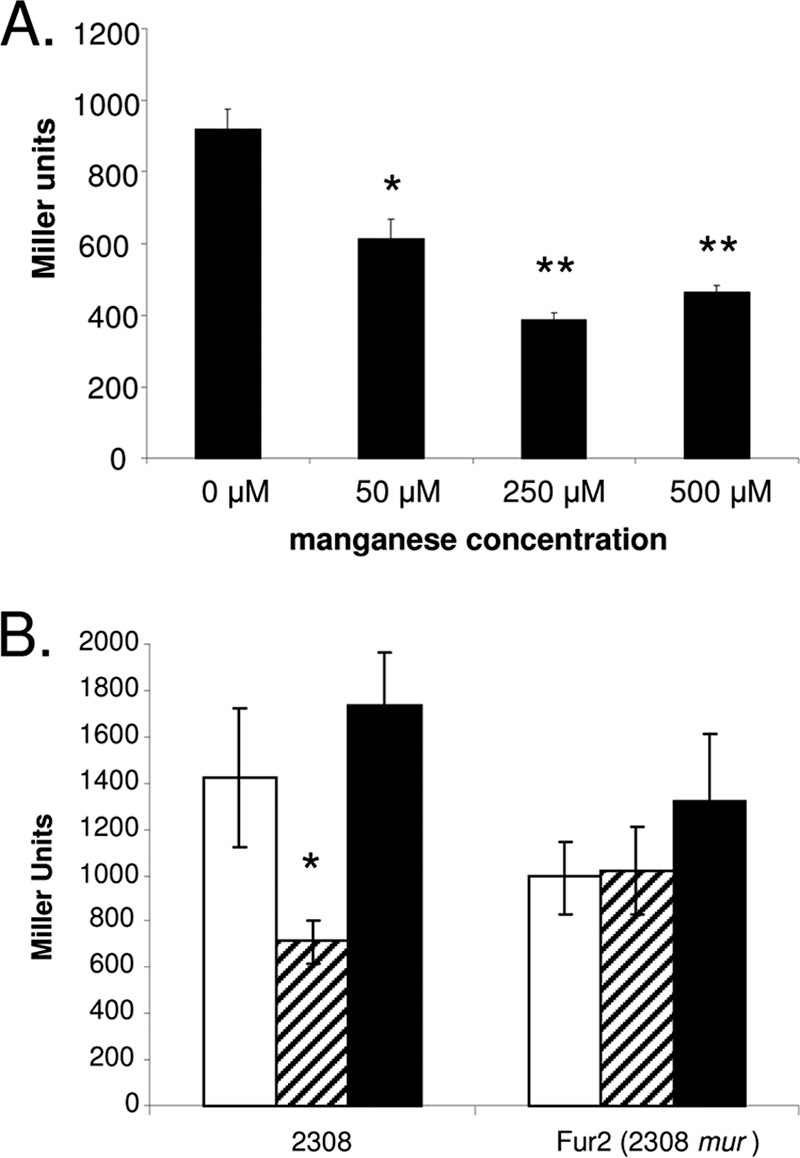

The B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 displays extreme attenuation compared to the parent strain in both cultured murine macrophages (Fig. 6) and experimentally infected mice (Fig. 7). In both cases, the attenuation of the B. abortus mntH mutant is alleviated by the introduction of a plasmid-borne copy of the parental mntH gene into this strain.

FIG. 6.

Survival and replication of B. abortus 2308 (▴), MWV15 (2308 mntH) (□), and MWV15C [MWV15(pEA31)] (▪) in cultured resident peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6 mice. The data are means and standard deviations of the number of intracellular brucellae recovered for each strain from three separate wells of cultured macrophages at each experimental time point in a single experiment. The data are representative of multiple (≥3) experiments from which equivalent results and statistical trends were obtained. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (for comparisons of MWV15 with 2308 and MWV15.C).

FIG. 7.

Spleen colonization profiles of B. abortus 2308 (▴), MWV15 (2308 mntH) (□), and MWV15.C [MWV15(pEA31)] (▪) in C57BL/6 mice. The data presented are means and standard deviations of the number of brucellae detected in the spleens of five mice infected with each strain at each experimental time point in a single experiment. **, P < 0.005 (for comparisons of MWV15 with 2308 and MWV15.C).

DISCUSSION

The experimental findings presented in this paper support the proposition that MntH serves as the sole high-affinity manganese transporter in B. abortus 2308. A similar role for MntH in Bradyrhizobium japonicum, a close phylogenetic relative of brucellae, has also recently been described (37). Many bacteria contain both proton-dependent (MntH-type) and ATP-dependent (SitABCD-type) Mn2+ transporters, and mutation of both the mntH and sitABCD genes is often required before prominent defects in Mn2+ utilization are observed (8, 65). This is clearly not the case with the B. abortus mntH mutant, where loss of MntH produces prominent growth defects in both rich and minimal growth media that can be relieved only by supplementation of these media with elevated levels of Mn2+. It is important to note, however, that the B. abortus mntH mutant eventually attains the same cell density as the parental strain in a manganese-deprived minimal medium (Fig. 2), and the addition of high levels of MnCl2 (e.g., 7.95 mM) to disks will allow this strain to grow on plates containing EDDA (Table 1). These experimental findings demonstrate that B. abortus 2308 has an alternate means of acquiring Mn2+ when MntH is not present, but this alternate mechanism is apparently much less efficient at Mn2+ transport than MntH.

Like its counterparts in other bacteria (41), Brucella MntH appears to be a manganese-selective transporter. Although supplementation of the culture medium with Mn2+ relieves the growth defects exhibited by the B. abortus mntH mutant when this strain is grown in a rich medium or low-manganese minimal medium, supplementation of these media with other divalent cations reported to be transported by Nramp/MntH homologs (e.g., Fe2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, and Cu2+) (34, 52) does not. Particular attention was paid to the possibility that MntH might also be playing a role in iron transport in B. abortus 2308 because other prokaryotic MntH homologs have the ability to transport Fe2+ at least under laboratory conditions (1, 41, 52) and efficient iron acquisition has been reported to be an important virulence determinant for this bacterium in both natural (6) and experimental (56) hosts. Although no experimental evidence linking MntH to iron transport in B. abortus 2308 was obtained during this study, such a role cannot be definitively ruled out without further experimental evaluation.

Mur, rather than MntR, appears to be the major regulator of Mn2+ acquisition genes in most of the alphaproteobacteria that have been examined (16, 21, 37, 45, 58, 62). Thus, the fact that mntH expression in B. abortus 2308 is regulated by manganese in a Mur-dependent manner, but is not responsive to iron, is also consistent with the role of MntH as a manganese-selective transporter. The observation that mntH apparently exhibits a relatively high level of basal expression during growth in a nutritionally replete medium may be a reflection of the critical role that MntH plays in providing this bacterium with sufficient levels of Mn2+ to meet its physiologic needs and the low toxicity exhibited by Mn2+ compared to other divalent cations (43). The precise nature of the regulatory link between mntH, Mur, and cellular Mn levels in B. abortus 2308 is presently being examined. A computational analysis of the B. melitensis 16M genome sequence suggests that the Brucella Mur regulon may be limited to only a few genes other than mntH (62).

In most bacteria that have been studied, there is a strong link between the ability to acquire Mn2+ and resistance to oxidative stress (39), and this same relationship is observed for B. abortus 2308 and the isogenic mntH mutant MWV15. Activity gels indicate that MWV15 produces considerably lower levels of Mn SOD activity than the parental strain, and this deficit in SodA activity is consistent with the increased sensitivity of the B. abortus mntH mutant to the redox cyclers menadione and paraquat, which generate O2− in the cytoplasmic compartment of bacterial cells. This link between inefficient Mn2+ transport and suboptimal levels of SOD activity is also similar to the one described for Sinorhizobium meliloti sitA mutants (19). It is quite possible, however, that the increased sensitivity of the mutant B. abortus mntH mutant to oxidative stress results from defects in addition to its inability to produce wild-type levels of SodA. Anjem et al. (2), for example, recently presented evidence suggesting that MntH-mediated Mn2+ transport allows E. coli to metalate key metabolic enzymes with this divalent cation instead of Fe2+, possibly protecting these enzymes from oxidative damage via Fenton chemistry. Those authors also showed that MntH-dependent Mn2+ transport is an important component of this bacterium's OxyR-mediated response to H2O2 exposure. Intracellular levels of Mn2+ can also influence the activity of transcriptional regulators such as PerR that control the expression of genes important for resistance to oxidative stress (38, 49, 70). Preliminary studies suggest that the gene annotated as BAB1_0393 in the B. abortus 2308 genome sequence may be a PerR homolog (E. S. Anderson, unpublished data), but the nature of the genes that are controlled by this putative regulator and whether or not the activity of the regulator is influenced by cellular Mn2+ levels remain to be determined experimentally. Mn2+ has also been shown to be able to directly detoxify H2O2 and O2− in in vitro assays (3, 69). It has been postulated, however, that only a few bacteria such as lactobacilli have the capacity to accumulate sufficient levels of Mn2+ (e.g., mM) to make direct intracellular detoxification of ROS by this metal biologically significant (39). Previous studies have shown that wild-type Brucella strains require low levels of manganese for growth (28, 66), and those findings are supported by the growth properties exhibited by B. abortus 2308 in the study reported here (Fig. 1). Thus, it seems unlikely that direct detoxification of ROS by intracellular Mn2+ plays a major role in oxidative defense in Brucella strains.

Nramp1-mediated efflux of Mn2+ and other divalent cations from the phagosomal compartments of macrophages has been proposed to be an important component of host defense against intracellular pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (12, 40). Studies have shown, however, that Nramp1 does not play a prominent role in protecting experimentally infected mice from Brucella infections (33). Studies of ruminants have also shown that the contributions of this divalent cation transporter to host defense against Brucella infections vary depending on the species of ruminant being examined (10, 54). Thus, the severe attenuation exhibited by the B. abortus mntH mutant in C57BL/6 mice (which lack a functional Nramp1) (67) and cultivated macrophages obtained from these mice is particularly striking. This is especially true considering the fact that bacterial mntH mutants often exhibit subtle, if any, attenuation in experimental hosts (8, 22), and significant attenuation of S. Typhimurium mntH sitABCD double mutants (which lack both of their high-affinity manganese transporters) is seen only in mice that have a functional Nramp1 locus (72). These findings suggest that Mn2+, like Mg2+ and Zn2+ (44, 48, 71), represents an important micronutrient for brucellae during residence in the mammalian host. They also suggest that the levels of Mn2+ present in the tissues of experimentally infected C57BL/6 mice are insufficient to meet the physiologic requirements of the B. abortus mntH mutant for this divalent cation even in the absence of a functional Nramp1 in this mammalian host. Considering the dramatic effect that the loss of MntH has on virulence in B. abortus 2308, it is intriguing that brucellae rely on a single high-affinity divalent cation transporter to meet their physiologic needs for Mn2+ during intracellular replication. Indeed, having only one high-affinity Mn2+ transporter appears to be an “Achilles' heel” for these bacteria during residence in the mammalian host. Most other bacterial pathogens that have been studied possess both MntH- and SitABCD-type Mn2+ transporters (55). The bacterial SitABCD-type transporters that have been studied in detail, however, have been reported to be unable to transport Mn2+ at an acidic pH (42, 55), and thus, this type of transporter might be of limited utility to brucellae during the early stages of their intracellular residence in host macrophages when these bacteria occupy acidified compartments (7, 46). In contrast, if Brucella MntH is similar to its Salmonella counterpart (41) and exhibits optimum Mn2+ transport at an acidic pH, it would appear to be well suited to the intracellular lifestyle of brucellae in their mammalian hosts.

There are multiple reasons that an insufficient level of intracellular Mn2+ could lead to attenuation in the B. abortus mntH mutant. Based on its sensitivity to oxidative killing, the B. abortus mntH mutant may be compromised in its ability to withstand the oxidative stresses it encounters during its interactions with host phagocytes. Brucella spp. also produce a single bifunctional (p)ppGpp synthetase/hydrolase that has been given the designation Rsh (RelA/SpoT hybrid) (24), and the enzymatic activity of this class of bacterial proteins is Mn2+ dependent (55). Because production of (p)ppGpp is required for a stringent response in bacteria (51), reduced Rsh activity due to inadequate Mn2+ levels in the B. abortus mntH mutant may interfere with this strain's ability to cope with the nutrient deprivation encountered during long-term residence in the phagosome of host macrophages (46, 63). The presence of a functional Rsh protein has also been shown to be required for the proper expression of the virB genes, which encode the type IV secretion machinery in B. melitensis 16M and Brucella suis 1330 (24). Consequently, inefficient expression of the virB genes due to reduced Rsh function could also be contributing to the attenuation exhibited by the B. abortus mntH mutant in macrophages and mice. Preliminary studies suggest that virB4 and virB5 expression levels are indeed reduced in the B. abortus mntH mutant MWV15 compared to those in the parental 2308 strain (J. Gaines and E. Anderson, unpublished data), but the nature of the link between MntH and virB expression remains to be experimentally determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants (AI48499 and AI63516) from the National Institutes of Health to R.M.R.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agranoff, D., I. M. Monahan, J. A. Mangan, P. D. Butcher, and S. Krishna. 1999. Mycobacterium tuberculosis expresses a novel pH-dependent divalent cation transporter belonging to the Nramp family. J. Exp. Med. 190717-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anjem, A., S. Varghese, and J. A. Imlay. 2009. Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 72844-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald, F. S., and I. Fridovich. 1982. The scavenging of superoxide radical by manganese complexes: in vitro. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 214452-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bearden, S. W., and R. D. Perry. 1999. The Yfe system of Yersinia pestis transports iron and manganese and is required for full virulence of plague. Mol. Microbiol. 32403-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellaire, B. H. 2001. Ph.D. thesis. Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport.

- 6.Bellaire, B. H., P. H. Elzer, S. Hagius, J. Walker, C. L. Baldwin, and R. M. Roop II. 2003. Genetic organization and iron-responsive regulation of the Brucella abortus 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid biosynthesis operon, a cluster of genes required for wild-type virulence in pregnant cattle. Infect. Immun. 711794-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellaire, B. H., R. M. Roop II, and J. A. Cardelli. 2005. Opsonized virulent Brucella abortus replicates within nonacidic, endoplasmic reticulum-negative, LAMP-1-positive phagosomes in human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 733702-3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer, E., I. Bergevin, D. Malo, P. Gros, and M. F. M. Cellier. 2002. Acquisition of Mn(II) in addition to Fe(II) is required for full virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 706032-6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capparelli, R., F. Alfano, M. Grazia Amoroso, G. Borriello, D. Fenizia, A. Bianco, S. Roperto, F. Roperto, and D. Iannelli. 2007. Protective effect of the Nramp1 BB genotype against Brucella abortus in the water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Infect. Immun. 75988-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlioz, A., and D. Touati. 1986. Isolation of superoxide dismutase mutants in Escherichia coli: is superoxide dismutase necessary for aerobic life? EMBO J. 5623-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cellier, M. F., P. Courville, and C. Campion. 2007. Nramp1 phagocyte intracellular metal withdrawal defense. Microbes Infect. 91662-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaberek, S., and A. E. Martell. 1959. Organic sequestering agents. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

- 14.Chain, P. S. G., D. J. Comerci, M. E. Tomalsky, F. W. Larimer, S. A. Malfatti, L. M. Vergez, F. Aguero, M. L. Land, R. A. Ugalde, and E. Garcia. 2005. Whole-genome analyses of speciation events in pathogenic brucellae. Infect. Immun. 738353-8361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaloupka, R., P. Courville, F. Veyrier, B. Knudsen, T. A. Tompkins, and M. F. M. Cellier. 2005. Identification of functional amino acids in the Nramp family by a combination of evolutionary analysis and biophysical studies of metal and proton cotransport in vivo. Biochemistry 44726-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao, T.-C., A. Becker, J. Buhrmester, A. Pühler, and S. Weidner. 2004. The Sinorhizobium meliloti fur gene regulates, with dependence on Mn(II), transcription of the sitABCD operon, encoding a metal-type transporter. J. Bacteriol. 1863609-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbel, M. J. 1997. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3213-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox, C. D. 1994. Deferration of laboratory media and assays for ferric and ferrous ions. Methods Enzymol. 235315-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies, B. W., and G. C. Walker. 2007. Disruption of sitA compromises Sinorhizobium meliloti for manganese uptake required for protection against oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 1862101-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DelVecchio, V. G., V. Kapatral, R. J. Redkar, G. Patra, C. Mujer, T. Los, N. Ivanova, I. Anderson, A. Bhattacharyya, A. Lykidis, G. Reznik, L. Jablonski, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, A. Bernal, M. Mazur, E. Goltsman, E. Selkov, P. H. Elzer, S. Hagius, D. O'Callaghan, J. J. Letesson, R. Haselkorn, N. Kyrpides, and R. Overbeek. 2002. The genome sequence of the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Mireles, E., M. Wexler, G. Sawers, D. Bellini, J. D. Todd, and A. W. B. Johnston. 2004. The Fur-like protein Mur of Rhizobium leguminosarum is a Mn(2+)-responsive transcriptional regulator. Microbiology 1501447-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domenech, P., A. S. Pym, M. Cellier, C. E. Barry III, and S. T. Cole. 2002. Inactivation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nramp orthologue (mntH) does not affect virulence in the mouse model of tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 20781-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorrell, N., V. G. Gyselman, S. Foynes, S. R. Li, and B. W. Wren. 1996. Improved efficiency of inverse PCR mutagenesis. BioTechniques 21604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dozot, M., R.-A. Boigegrain, R.-M. Delrue, R. Hallez, S. Ouahrani-Bettache, I. Danese, J.-J. Letesson, X. de Bolle, and S. Köhler. 2006. The stringent response mediator Rsh is required for Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis virulence, and for expression of the type IV secretion system virB. Cell. Microbiol. 81791-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elzer, P. H., R. W. Phillips, M. E. Kovach, K. M. Peterson, and R. M. Roop II. 1994. Characterization and genetic complementation of a Brucella abortus high-temperature-requirement A (htrA) deletion mutant. Infect. Immun. 624135-4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elzer, P. H., R. W. Phillips, G. T. Robertson, and R. M. Roop II. 1996. The HtrA stress response protease contributes to the resistance of Brucella abortus to killing by murine phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 644838-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enright, F. M. 1990. The pathogenesis and pathobiology of Brucella infections in domestic animals, p. 301-320. In K. H. Nielsen and J. R. Duncan (ed.), Animal brucellosis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 28.Evenson, M. A., and P. Gerhardt. 1955. Nutrition of brucellae: utilization of iron, magnesium and manganese for growth. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 89678-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gee, J. M. 2004. Ph.D. thesis. Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Gee, J. M., M. W. Valderas, M. E. Kovach, V. K. Grippe, G. T. Robertson, W.-L. Ng, J. M. Richardson, M. E. Winkler, and R. M. Roop II. 2005. The Brucella abortus Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase is required for optimal resistance to oxidative killing by murine macrophages and wild-type virulence in experimentally infected mice. Infect. Immun. 732873-2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerhardt, P. 1958. The nutrition of brucellae. Microbiol. Rev. 2281-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gober, J. W., and L. Shapiro. 1992. A developmentally regulated Caulobacter flagellar promoter is activated by 3′ enhancer and IHF binding elements. Mol. Biol. Cell 3913-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guilloteau, L. A., J. Dornand, A. Gross, M. Olivier, F. Cortade, Y. L. Vern, and D. Kerboeuf. 2003. Nramp1 is not a major determinant in the control of Brucella melitensis infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 71621-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunshin, H., B. Mackenzie, U. V. Berger, Y. Gunshin, M. F. Romero, W. F. Boron, S. Nussberger, J. L. Gollan, and M. A. Hediger. 1997. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 388482-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haemig, H. A. H., and R. J. Brooker. 2004. Importance of conserved acidic residues in MntH, the Nramp homolog of Escherichia coli. J. Membr. Biol. 20197-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halling, S. M., B. D. Peterson-Burch, B. J. Bricker, R. L. Zuerner, Z. Qing, L. L. Li, V. Kapur, D. P. Alt, and S. C. Olsen. 2005. Completion of the genome sequence of Brucella abortus and comparison to the highly similar genomes of Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis. J. Bacteriol. 1872715-2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hohle, T. M., and M. R. O'Brian. 2009. The mntH gene encodes the major Mn2+ transporter in Bradyrhizobium japonicum and is regulated by manganese via the Fur protein. Mol. Microbiol. 72399-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horsburgh, M. J., S. J. Wharton, A. G. Cox, E. Ingham, S. Peacock, and S. J. Foster. 2002. MntR modulates expression of the PerR regulon and superoxide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus through control of manganese uptake. Mol. Microbiol. 441269-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horsburgh, M. J., S. J. Wharton, M. Karavolos, and S. J. Foster. 2002. Manganese: elemental defence for a life with oxygen. Trends Microbiol. 10496-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jabado, N., A. Jankowski, S. Dougaparsad, V. Picard, S. Grinstein, and P. Gros. 2000. Natural resistance to intracellular infections: natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (NRAMP1) functions as a pH-dependent manganese transporter at the phagosomal membrane. J. Exp. Med. 1921237-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kehres, D. G., M. L. Zaharik, B. B. Finlay, and M. E. Maguire. 2000. The NRAMP proteins of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli are selective manganese transporters involved in the response to reactive oxygen. Mol. Microbiol. 361085-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kehres, D. G., A. Janakiraman, J. M. Slauch, and M. E. Maguire. 2002. SitABCD is the alkaline Mn2+ transporter of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1843159-3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kehres, D. G., and M. E. Maguire. 2003. Emerging themes in manganese transport, biochemistry and pathogenesis in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27263-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim, S., K. Watanabe, T. Shirahata, and M. Watarai. 2004. Zinc uptake system (znuA locus) of Brucella abortus is essential for intracellular survival and virulence in mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 661059-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitphati, W., P. Ngok-Ngam, S. Suwanmaneerat, R. Sukchawalit, and S. Mongolsuk. 2007. Agrobacterium tumefaciens fur has important physiological roles in iron and manganese homeostasis, the oxidative stress response, and full virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 734760-4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Köhler, S., S. Michaux-Charachon, F. Porte, M. Ramuz, and J.-P. Liautard. 2003. What is the nature of the replicative niche of a stealthy bug named Brucella? Trends Microbiol. 11215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langford, P. R., A. Sansone, P. Valenti, A. Battistoni, and J. S. Kroll. 2002. Bacterial superoxide dismutases and virulence. Methods Enzymol. 349155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavigne, J.-P., D. O'Callaghan, and A.-B. Blanc-Potard. 2005. Requirement of MgtC for Brucella suis intramacrophage growth: a potential mechanism shared by Salmonella enterica and Mycobacterium tuberculosis for adaptation to a low-Mg2+ environment. Infect. Immun. 733160-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee, J.-W., and J. D. Helmann. 2006. Biochemical characterization of the structural Zn2+ site in the Bacillus subtilis peroxide sensor PerR. J. Biol. Chem. 28123567-23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.López-Goñi, I., I. Moriyón, and J. B. Neilands. 1992. Identification of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid as a Brucella abortus siderophore. Infect. Immun. 604496-4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magnusson, L. U., A. Farewell, and T. Nystrom. 2005. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 13236-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makui, H., E. Roig, S. T. Cole, J. D. Helmann, P. Gros, and M. F. M. Cellier. 2000. Identification of the Escherichia coli K-12 Nramp orthologue (MntH) as a selective divalent metal ion transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 351065-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 352-355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 54.Paixão, T. A., F. P. Poester, A. V. Carvalho Neta, A. M. Borges, A. P. Lage, and R. L. Santos. 2007. NRAMP1 3′ untranslated region polymorphisms are not associated with natural resistance to Brucella abortus in cattle. Infect. Immun. 752493-2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papp-Wallace, K. M., and M. E. Maguire. 2006. Manganese transport and the role of manganese in virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60187-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paulley, J. T., E. S. Anderson, and R. M. Roop II. 2007. Brucella abortus requires the heme transporter BhuA for maintenance of chronic infection in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 755248-5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paulsen, I. T., R. Seshadri, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, T. D. Read, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. M. Brinkac, M. J. Beanan, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Dolonay, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, B. Ayodeji, M. Kraul, J. Shetty, J. Malek, S. E. Van Aken, S. Riedmuller, H. Tettelin, S. R. Gill, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, D. L. Hoover, L. E. Lindler, S. M. Halling, S. M. Boyle, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. The Brucella suis genome reveals fundamental similarities between animal and plant pathogens and symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99231-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Platero, R., L. Peixoto, M. R. O'Brian, and E. Fabiono. 2004. Fur is involved in manganese-dependent regulation of mntA (sitA) expression in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 704349-4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Platero, R. A., M. Jaureguy, F. J. Battistoni, and E. R. Fabiano. 2003. Mutations in sitB and sitD genes affect manganese-growth requirements in Sinorhizobium meliloti. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 21865-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Que, Q., and J. D. Helmann. 2000. Manganese homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis is regulated by MntR, a bifunctional regulator related to the diphtheria toxin repressor family of proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 351454-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robertson, G. T., M. E. Kovach, C. A. Allen, T. A. Ficht, and R. M. Roop II. 2000. The Brucella abortus Lon functions as a generalized stress response protease and is required for wild-type virulence in BALB/c mice. Mol. Microbiol. 35577-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodionov, D. A., M. S. Gelfand, J. D. Todd, A. R. J. Curson, and A. W. B. Johnston. 2006. Computational reconstruction of iron- and manganese-responsive transcriptional networks in α-proteobacteria. PLoS Comput. Biol. 21568-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roop, R. M., II, B. H. Bellaire, M. W. Valderas, and J. M. Cardelli. 2004. Adaptation of the brucellae to their intracellular niche. Mol. Microbiol. 52621-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosner, B. 2000. Fundamentals of biostatistics, 5th ed. Duxbury, Pacific Grove, CA.

- 65.Runyen-Janecky, L., E. Dazenski, S. Hawkins, and L. Warner. 2006. Role and regulation of the Shigella flexneri Sit and MntH systems. Infect. Immun. 744666-4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanders, T. H., K. Higuchi, and C. R. Brewer. 1953. Studies on the nutrition of Brucella melitensis. J. Bacteriol. 66294-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Skamene, E., P. Gros, P. A. Kongshavn, C. St. Charles, and B. A. Taylor. 1982. Genetic regulation of resistance to intracellular pathogens. Nature 297506-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sriranganathan, N., S. M. Boyle, G. Schurig, and H. Misra. 1991. Superoxide dismutases of virulent and avirulent strains of Brucella abortus. Vet. Microbiol. 26359-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stadtman, E. R., B. S. Berlett, and P. B. Chock. 1990. Manganese-dependent disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide in bicarbonate buffer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87384-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, H.-J., K. L. Seib, Y. N. Srikhanta, S. P. Kidd, J. L. Edwards, T. L. Maguire, S. M. Grimmond, M. A. Apicella, A. G. McEwan, and M. P. Jennings. 2006. PerR controls Mn-dependent resistance to oxidative stress in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 60401-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang, X., T. Becker, N. Walters, and D. W. Pascual. 2006. Deletion of znuA virulence factor attenuates Brucella abortus and confers protection against wild-type challenge. Infect. Immun. 743874-3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zaharik, M. L., V. L. Cullen, A. M. Fung, S. J. Libby, S. L. K. Choy, B. Coburn, D. G. Kehres, M. E. Maguire, F. C. Fang, and B. B. Finlay. 2004. The Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium divalent cation transport systems MntH and SitABCD are essential for virulence in an Nramp1G169 murine typhoid model. Infect. Immun. 725522-5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]