Abstract

Host immunity is a major driving force of antigenic diversity, resulting in pathogens that can evade immunity induced by closely related strains. Here we show that two Bordetella bronchiseptica strains, RB50 and 1289, express two antigenically distinct O-antigen serotypes (O1 and O2, respectively). When 18 additional B. bronchiseptica strains were serotyped, all were found to express either the O1 or O2 serotype. Comparative genomic hybridization and PCR screening showed that the expression of either the O1 or O2 serotype correlated with the strain containing either the classical or alternative O-antigen locus, respectively. Multilocus sequence typing analysis of 49 B. bronchiseptica strains was used to build a phylogenetic tree, which revealed that the two O-antigen loci did not associate with a particular lineage, evidence that these loci are horizontally transferred between B. bronchiseptica strains. From experiments using mice vaccinated with purified lipopolysaccharide from strain RB50 (O1), 1289 (O2), or RB50Δwbm (O antigen deficient), our data indicate that these O antigens do not confer cross-protection in vivo. The lack of cross-immunity between O-antigen serotypes appears to contribute to inefficient antibody-mediated clearance between strains. Together, these data are consistent with the idea that the O-antigen loci of B. bronchiseptica are horizontally transferred between strains and encode antigenically distinct serotypes, resulting in inefficient cross-immunity.

One of the most commonly studied examples of antigenic diversity in bacteria is O antigen, a highly variable membrane-distal region of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that is known for protecting gram-negative bacteria from complement-mediated killing and the bactericidal effects of antimicrobial peptides (10, 27, 37). Upon infection, O antigens induce a robust antibody response, the specificity of which can be used to group microorganisms into serotypes (37). Evidence of horizontal gene transfer of O-antigen loci between strains or species has been detected, and more than 100 serotypes can exist in some species (12, 26, 36-38). O-antigen diversity can allow strains to escape cross-immunity, which can lead to the coexistence of closely related strains that circulate in the same host population, as has been observed with Vibrio cholerae, typhoidal Salmonella, and the human-adapted Bordetella species (4, 18, 21, 24).

The genus Bordetella includes a group of closely related respiratory pathogens that cause a variety of diseases in a broad range of animals (B. bronchiseptica) and whooping cough in humans (B. pertussis and B. parapertussis). In Bordetella, the lpx, waa, wlb, and wbm loci encode the lipid A, the inner core, the trisaccharide, and the O-antigen regions of LPS, respectively (30, 32). While many of these LPS-related genes are shared between these species, there are species-specific differences. For example, the lipid A acylation patterns differ in each species, even though the lpx genes are nearly identical and the trisaccharide is not synthesized by B. parapertussis, likely due to a point mutation in the wlb locus (1, 30). Additionally, while B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis express an O antigen, the wbm locus has been deleted from B. pertussis, resulting in a lack of O-antigen synthesis (30, 32). The O antigens of B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis are highly antigenic (41, 42), increase their resistance to complement-mediated killing (7, 10), and contribute to the ability of these species to colonize the lower respiratory tract of mice (7, 10).

In B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis, the O antigen has been described as a polymer of 2,3-di-N-acetyl-galactosaminuronic acid, where some residues are present as uronamides or it is decorated by a number of unusual substitutions (35, 40). The O-antigen locus contains 24 genes and spans more than 29 kb (30, 32). The first 14 genes, wbmA to wbmN, are nearly identical between species and are thought to be involved in the synthesis of the O-antigen polymer, its linkage to the trisaccharide or core region, and O-antigen export (30, 32, 34). The last three genes, BB0121 to BB0123, are also nearly identical and are therefore proposed to be involved in the synthesis of some common structure (30, 32, 34). Between these two highly conserved regions, there are seven genes, which are either weakly conserved or locus specific, indicating that these genes may synthesize type-specific modifications (30, 32, 34). More specifically, while B. bronchiseptica strain RB50 contains the classical wbm genes (wbmO, wbmR, and wbmS and BB0124 to BB0127), B. parapertussis strain 12822 and B. bronchiseptica strain CN7635E contain the alternative O-antigen genes (wbmOPQRSTU) (30, 32). While only the alternative locus has been found in B. parapertussis strains, B. bronchiseptica strains can harbor either the classical or alternative locus (9, 30, 32), which has led to the hypothesis that different O-antigen loci cause differences in structure and antigenicity between B. bronchiseptica strains (30). Previous studies have shown that the locus type correlates with particular structural modifications, since the classical or alternative loci correlate with an Ala-type or Lac-type modification on the nonreducing, terminal sugar residue of O antigen, respectively (22, 30, 35). These modifications correspond to different reactivities of the O antigen to monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies (22, 40; A. Preston, unpublished data). However, it has not been previously determined if the O-antigen serotype correlates with locus type.

While the maintenance of different O-antigen loci, structures, and serotypes in B. bronchiseptica likely has important epidemiological consequences, the molecular evolution of these O-antigen loci and their role in evading cross-immunity in an experimental model of infection have not been examined. Here, we use a broad range of approaches to shed light on these questions. We determined that nearly all B. bronchiseptica strains express one of two antigenically distinct O-antigen serotypes that are not cross-reactive, which correlates with the presence of either the classical or alternative O-antigen locus. Using comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and PCR screening, the expression of either the O1 or O2 serotype was shown to correlate with the strain containing either the classical or alternative O-antigen locus, respectively. When multilocus sequence typing (MLST) data of 49 B. bronchiseptica strains were used to build a phylogenetic tree, it showed that the presence of these loci do not correlate with a particular phylogenetic lineage, suggesting that they are horizontally transferred between B. bronchiseptica strains. Additionally, the O antigen from these strains did not induce cross-protective immunity between strains, and this appears to contribute to inefficient antibody-mediated cross-protection in a murine model of infection. Our data are consistent with the idea that the O-antigen serotypes of B. bronchiseptica are encoded by separate, horizontally transferred O-antigen loci, which contributes to inefficient cross-immunity between strains. We discuss the importance of this work in terms of the maintenance of pathogen strain structure and epidemiological consequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and LPS preparation.

All wild-type B. bronchiseptica isolates and available information regarding source, location, date, anatomical site of isolation, reference, and all available health status reports have been previously described (6, 6a, 8, 9). Strain RB50Δwbm is an isogenic mutant of strain RB50 that lacks O-antigen expression due to deletion of wbmB to wbmD and the N-terminal half of wbmE (7, 33). All strains were maintained on Bordet-Gengou agar (Difco, Sparks, MD) containing 10% sheep's blood (Hema Resources, Aurora, OR) with 20 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). LPS was purified from strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm as described previously (16) using a modification of the method of Hitchcock and Brown (2, 17).

Western blots.

Western blotting was performed essentially as described previously (6, 42). Briefly, B. bronchiseptica strains were grown to logarithmic phase in Stainer-Scholte (SS) broth. The appropriate strain (1 × 108 CFU) was treated with Laemmli sample buffer (23) and run on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, and protein was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were probed with convalescent-phase serum from RB50- or 1289- inoculated mice (1:1,500 dilution) and goat antimouse (immunoglobulin H+L) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (1:10,000) antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). All membranes were visualized with ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

ELISAs.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) experiments were carried out essentially as described previously (28, 41). Whole-cell bacteria or purified LPS from the indicated strains were diluted to 7 × 106 CFU/ml or 50 μg/ml in a 1:1 mix of 0.2 M sodium carbonate and 0.2 M sodium bicarbonate buffers, respectively. These antigens were added to each well of a 96-well plate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified chamber. A 1:50 dilution of each serum sample was added to the first well and serially diluted across the plates. After another incubation period, the plates were washed and goat antimouse (immunoglobulin H+L) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:10,000 dilution) was added. After another incubation period, plates were washed and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) in a phosphocitrate buffer and hydrogen peroxide were added to wells and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark and read on a plate reader at 405 nm. The titer was calculated using an endpoint, slope-adapted method by comparison to wells treated with naive serum. Statistical significance in titers between bacterial strains or purified LPS was calculated by using an analysis of variance and Tukey simultaneous test in the Minitab software program (v. 13.30; Minitab Inc.). A P value of ≤0.05 was used for all experiments.

Comparative genomic hybridization and statistical analysis.

CGH analysis of strains RB50, 1289, and 253 has been described elsewhere (6, 6a). Briefly, strains RB50, 1289, and 253 were grown in SS broth, and genomic DNA was isolated using a DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and digested with DpnII. For each labeling reaction, 2 μg of digested genomic DNA was randomly primed using Cy-5 and Cy-3 dye-labeled nucleotides with BioPrime DNA labeling kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the two differentially labeled reactions to be compared were combined and hybridized to a B. bronchiseptica RB50-specific long-oligonucleotide microarray (6, 29). Dye swap experiments were performed. Statistical analysis of CGH data was performed with the SAS software program, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Regions of difference (RDs), meaning genes in strain RB50 that are either divergent or absent from the query strains, were identified using a MODECLUS procedure (PROC MODECLUS) based on nonparametric density estimation. All genes are labeled as annotated in the RB50 genome (30).

PCR.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the appropriate strains as described above and was screened for the classical wbm genes (forward, CATGGGTCGACGATTTCAGGAATGATGG; reverse, GAGACTAGCCAGGAGATTTATCATCCGC; product size = 728 bp, internal to BB0127 from NC_002927), alternative wbm genes (forward, CGATGTCGATGATTTTCGGTCGCTTG; reverse, CGAGCACGCATGCTCTTTATATGG; product size = 801 bp, internal to BPP0127/wbmR from NC_002928), and a housekeeping gene, adk (forward, AGCCGCCTTTCTCACCCAACACT; reverse, TGGGCCCAGGACGAGTAGT; product size = 513 bp, internal to BB2005) (9, 30). The same PCR conditions were used for all primer sets: 95°C for 5 min; 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C 1 min, 30 times; and 72°C for 5 min.

MLST and phylogenetic tree construction.

All data regarding MLST analysis have been described previously (6, 6a, 9). Using the MEGA 4.0 software program (39), the seven alleles sequenced from each strain were concatenated and aligned, and a neighbor-joining tree with 1,000 bootstraps using the K2 model was constructed for the indicated strains.

Animal care, inoculation, vaccination, and adoptive transfer protocols.

Four- to six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), bred, and maintained in our specific-pathogen- and Bordetella-free rooms at the Pennsylvania State University. For inoculation, bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in SS broth to mid-logarithmic phase and bacterial density was measured by an optical density read at 600 nm, followed by dilution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Omnipur, Gibbstown, NJ) to the appropriate concentration. Inocula were confirmed by plating dilutions on Bordet-Gengou agar and counting the resulting colonies after 2 days of incubation at 37°C as described previously (19, 20). For inoculation, mice were lightly sedated with 5% isofluorane (IsoFlo; Abbott Laboratories) in oxygen, and 104 CFU of the appropriate B. bronchiseptica strain in 50 μl of PBS was gently pipetted onto the external nares as previously described (19, 20). The bacterial load was determined by homogenizing the lung in 1 ml of PBS, diluting to the appropriate concentration, and plating aliquots. Two days later, the resulting colonies were counted (20). For vaccination studies, animals were immunized twice at 2-week intervals with 220 μl intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections containing 10 μg of the indicated LPS plus the Imject Alum adjuvant (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). One week after the last i.p. injection, mice received 50 μl containing 1 μg of the indicated LPS intranasally. One week after the intranasal vaccination, animals were challenged intranasally as described above and sacrificed on day 3 postchallenge for determination of colonization levels. For adoptive transfer of serum, an i.p. injection of 200 μl of convalescent-phase serum, obtained 28 days postinoculation from mice that were infected with either strain RB50, 1289, or RB50Δwbm, was given to naive mice, which were immediately inoculated with the appropriate bacterial strain. The mean ± standard error was determined for each treatment group. Statistical significance for the bacterial loads between strains was calculated by using an analysis-of-variance and Tukey simultaneous test in Minitab (v. 13.30; Minitab Inc.). A P value of ≤0.05 was used for all experiments. All animal experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results. All experiments were completed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Microarray data accession numbers.

All CGH data have been deposited in MIAMExpress under the accession numbers E-MEXP-1737 and E-MEXP-1205; they are available as supplemental data, which include the results from the statistical analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and are described elsewhere (6, 6a).

RESULTS

Bordetella bronchiseptica strains express antigenically distinct O-antigen serotypes.

When convalescent-phase sera collected from wild-type mice inoculated with either B. bronchiseptica strain RB50 or strain 1289 were used to probe strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm (an isogenic mutant of RB50 lacking O-antigen expression) (32) in Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A), we observed that these antibodies were not equally reactive to each strain. While strain RB50-induced sera recognized several antigens common to strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm, antibodies in this sera also recognized a broad smear of antigens (most prominent between 15 and 37 kDa) present in strain RB50 but not strain RB50Δwbm (Fig. 1A), which confirms previous reports showing that this smear is O antigen (42). The O-antigen smear is also absent in the lysate of strain 1289, which suggests that this strain either does not express O antigen or expresses an antigenically distinct O-antigen serotype (Fig. 1A). To distinguish between these possibilities, we probed the same lysates with convalescent-phase sera from mice infected with strain 1289. While an O-antigen smear was observed in the 1289 lysate, it was absent in both the RB50 and RB50Δwbm lysates (Fig. 1B). When lysates of strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm were probed with naive sera, no bands of recognition appeared on the Western blot, confirming that there was no nonspecific binding of antibodies (data not shown). Additionally, when these lysates were probed with RB50Δwbm-induced sera, the smear between 15 and 37 kDa did not appear, suggesting that this smear is in fact antibody recognition of O antigen (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when purified LPS from strain RB50Δwbm, RB50, or 1289 were probed with RB50- or 1289-induced sera (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that B. bronchiseptica strains RB50 and 1289 express two antigenically distinct O-antigen serotypes.

FIG. 1.

Recognition of B. bronchiseptica strains RB50 and 1289 using antibodies from convalescent-phase serum by Western blotting and ELISA. Western blots of B. bronchiseptica strain RB50-induced (A) or strain 1289-induced (B) sera were used to determine if antibodies raised against one strain recognized specific antigens of strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm (A and B). The numbers next to each Western blot indicate molecular weights (in thousands). ELISA was performed on RB50-induced (black), 1289-induced (dark gray), or RB50Δwbm-induced (light gray) serum to quantify titers of antibodies specific for strain RB50, 1289 or RB50Δwbm (C) or purified LPS from strain RB50, 1289 or RB50Δwbm (D). The dashed line represents the lower limit of detection. Asterisks denote P values of <0.05.

To quantify the cross-reactivities of antibodies to these B. bronchiseptica strains, we performed ELISA analysis using convalescent-phase sera from RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm infections. While all of these sera recognized whole-cell RB50 antigen, the recognition of this antigen by RB50-induced sera (titer of 15,500) was approximately 20- to 30-fold higher than that of either the 1289-induced (titer, 550; P < 0.0001) or RB50Δwbm-induced sera (titer, 400; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1C). When ELISA was performed using 1289 antigen, all sera were cross-reactive but the recognition from 1289-induced antibodies (titer, 19,700) was approximately 10- to 20-fold higher that of than either the RB50-induced (titer, 2,500; P < 0.0001) or RB50Δwbm-induced (titer, 1,000; P < 0.0001) sera (Fig. 1C). When these sera were analyzed using RB50Δwbm as the antigen, the difference in antibody recognition between strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm was abrogated (P > 0.3 for all comparisons), suggesting that the inefficient cross-reactivity of antibody responses between strains is caused by a difference in recognition of O antigen. Results similar to those described for the whole-cell antigen were obtained when purified LPS from strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm were used as the antigen (Fig. 1D). Combined, these data suggest that inefficient cross-reactivity of antibody responses between B. bronchiseptica strains RB50 and 1289 is due to the presence of two antigenically distinct O-antigen serotypes.

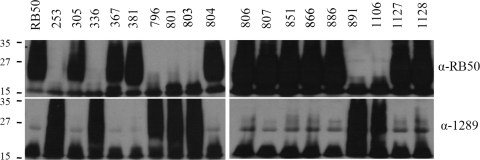

To determine if these 2 O-antigen serotypes were common to other B. bronchiseptica strains, 18 more strains were probed with either RB50- or 1289-induced sera using Western blot analysis. Strains 305, 367, 381, 804, 806, 807, 851, 866, 1127, and 1128 all contain an O antigen that was solely cross-reactive to RB50-induced sera (Fig. 2). In contrast, strains 253, 336, 796, 801, 803, 891, and 1106 contain an O antigen that was solely cross-reactive to 1289-induced sera (Fig. 2). None of the strains analyzed contained O antigens that were reactive to both RB50- and 1289-induced sera (Fig. 2). Thus, of the 19 B. bronchiseptica isolates analyzed here, only two O-antigen serotypes were identified. Together, these data indicate that these B. bronchiseptica strains express one of two O-antigen serotypes that are not cross-reactive. Hereafter, these serotypes are referred to as O1 (the RB50-like serotype) and O2 (the 1289-like serotype).

FIG. 2.

Determination of O-antigen serotype of 19 B. bronchiseptica strains by using convalescent-phase sera. B. bronchiseptica strain RB50-induced and strain 1289-induced sera were used to determine if serum raised against one strain recognized antigens the same size as O antigen in whole-cell lysates from the indicated strains. The numbers next to each Western blot indicate molecular weights (in thousands).

O-antigen serotype correlates with classical or alternative wbm genes.

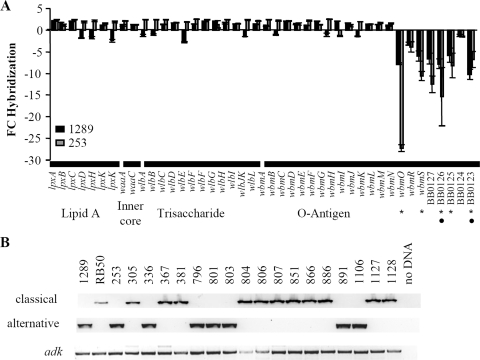

The expression of two antigenically distinct O antigens led us to examine the genetic basis for this difference. Using CGH analysis, the divergence of genes involved in LPS biosynthesis was analyzed between strain 1289 or 253 (both O2 serotypes) and strain RB50 (O1 serotype) (6, 6a). Lipid A (lpxA, lpxB, lpxC, lpxD, lpxH, lpxK, and lpxK), inner core (waaA and waaC), trisaccharide (wlbA to wlbJK and wlbL), and the majority of O-antigen-related genes (wbmA to wbmN) were not identified as RDs between strains RB50, 1289, and 253 (Fig. 3A). However, the most distal O-antigen-related genes, wbmO to wbmS and BB0123 to BB0127, appeared to be more highly divergent than the other LPS-related genes between strain 1289 or 253 and strain RB50 (Fig. 3A). The identification of distal wbm genes as RDs suggests that either these genes are present but have a low degree of homology or they are absent in strains 1289 and 253.

FIG. 3.

CGH and PCR analysis of LPS-related genes in B. bronchiseptica strains. (A) Comparison of LPS-related genes between strains RB50 and 1289 (black bars) or 253 (gray bars) using CGH analysis as described previously (6, 6a). The x axis indicates the gene analyzed and the LPS structure with which it is associated. The y axis indicates the n-fold change in hybridization (FC hybridization) for each gene. Negative n-fold or positive n-fold changes are indicative of decreased or increased hybridization of strain 1289 or 253 genomic DNA compared to results for strain RB50. Error bars represent standard errors. The circles and stars on the x axis indicate genes identified as RDs between strains RB50 and 1289 or 253, respectively. (B) PCR screen for the presence of the classical wbm genes, the alternative wbm genes, and adk in the indicated strains. A sample containing no DNA template was included to ensure the absence of DNA.

Previously, B. bronchiseptica strains were shown to harbor either the classical (wbmO to wbmR and BB0124 to BB0127) or alternative (wbmO to wbmU) O-antigen locus (30, 32). Therefore, we hypothesized that strains expressing the O1 or O2 serotype would contain the classical or alternative O-antigen locus, respectively. To test this, strains expressing the O1 or O2 serotype were PCR screened for the presence of classical or alternative O-antigen genes and a housekeeping gene, adenylate kinase (adk) (9). adk could be PCR amplified from all 20 B. bronchiseptica strains analyzed (Fig. 3B). The classical O-antigen gene, BB0127, could be PCR amplified from strains RB50, 305, 367, 381, 804, 806, 807, 851, 866, 886, 1127, and 1128 (Fig. 3B), which are all of the O1 serotype (Fig. 2). The alternative O-antigen gene, BPP0127/wbmR, could be PCR amplified from strains 1289, 253, 336, 796, 801, 803, 891, and 1106 (Fig. 3B), which are all of the O2 serotype (Fig. 1 and 2). Since strains 253 and 1289 are currently undergoing full-genome sequencing (6; A. M. Buboltz, X. Zhang, S. C. Schüster, E. T. Harvill, et al., unpublished data), we compared their O-antigen loci to the fully sequenced alternative O-antigen locus of B. parapertussis strain 12822 and found they were approximately 99% identical (data not shown). We did not identify a strain of the O1 serotype that contained the alternative O-antigen genes or an O2 serotype strain that contained the classical O-antigen genes (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that O1 strains contain the classical O-antigen genes while O2 strains contain the alternative O-antigen genes.

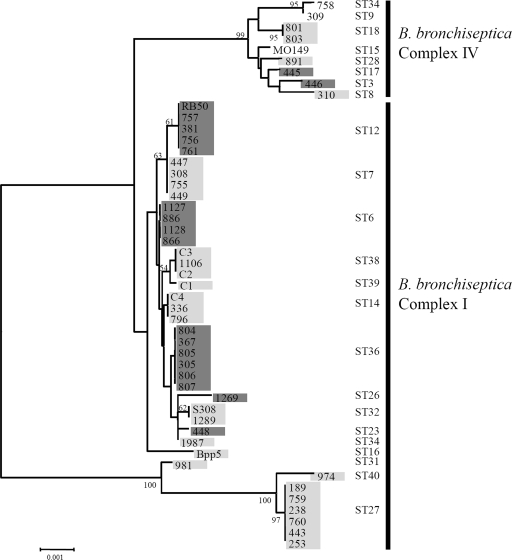

O-antigen serotype does not correspond to phylogenetic lineage.

In many gram-negative enteric bacteria, different loci encoding an O-antigen are not associated with phylogenetic lineage and therefore appear to be laterally transferred between strains or even species (18, 36). While enteric bacteria are known to coexist and transfer their O-antigen loci between strains, no previous evidence suggests that antigenic loci are horizontally transferred between B. bronchiseptica strains. In the absence of horizontal transfer, a distinct O-antigen locus would be expected to correlate with a particular lineage. To examine this, we completed MLST analysis and built a neighbor-joining tree containing 49 B. bronchiseptica strains, and then each strain was PCR screened for the presence of either the classical or alternative O-antigen genes (Fig. 4). Of the 49 strains analyzed, 19 strains contained the classical O-antigen genes and 27 strains contained the alternative O-antigen genes (Fig. 4). Three strains, all of which were complex IV isolates, did not contain either the classical or alterative O-antigen genes (strains MO149, 309, and 755) (Fig. 4). While the type of O-antigen locus did not vary within any sequence type (ST), both the classical and alternative O-antigen genes were distributed throughout the tree (Fig. 4). Combined, these data indicate that the classical and alternative O-antigen loci do not correspond to a particular lineage, providing evidence that these loci are horizontally transferred between B. bronchiseptica strains.

FIG. 4.

Mapping the presence of the classical or alternative O-antigen genes to ST in 49 B. bronchiseptica strains. A neighbor-joining tree with 1,000 bootstraps based on concatenated MLST gene sequence of 49 B. bronchiseptica isolates is shown. The identification number of each strain, the ST, and the complex to which each strain belongs are listed. STs and complexes have been described previously (6, 6a, 9). The highlighting indicates strains that contained either the classical (dark gray) or alternative (light gray) locus or were PCR negative for either locus (no highlighting). The numbers on the tree branches indicate branch strength. All branch strengths below 50 were removed.

O-antigen serotypes contribute to inefficient cross-immunity between B. bronchiseptica strains.

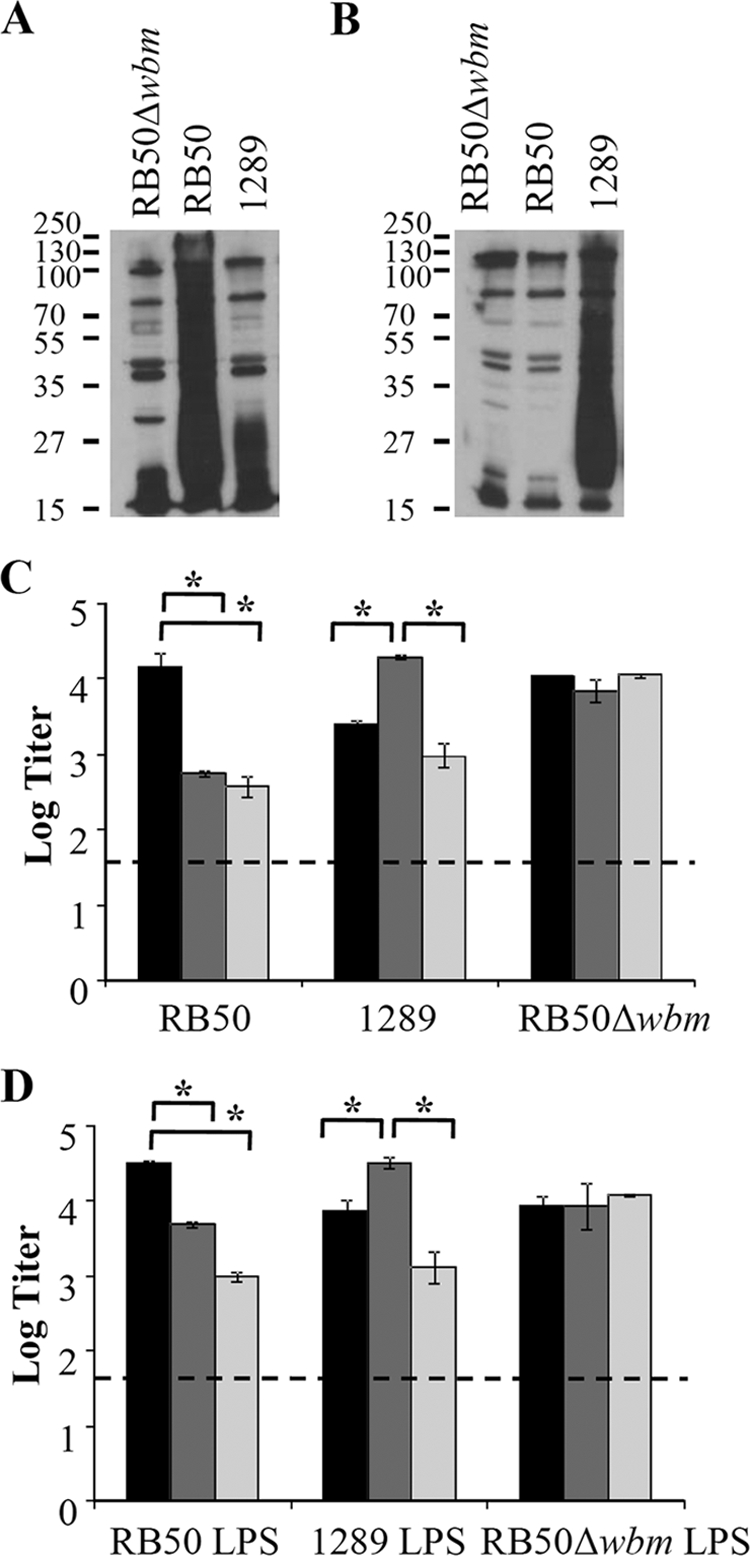

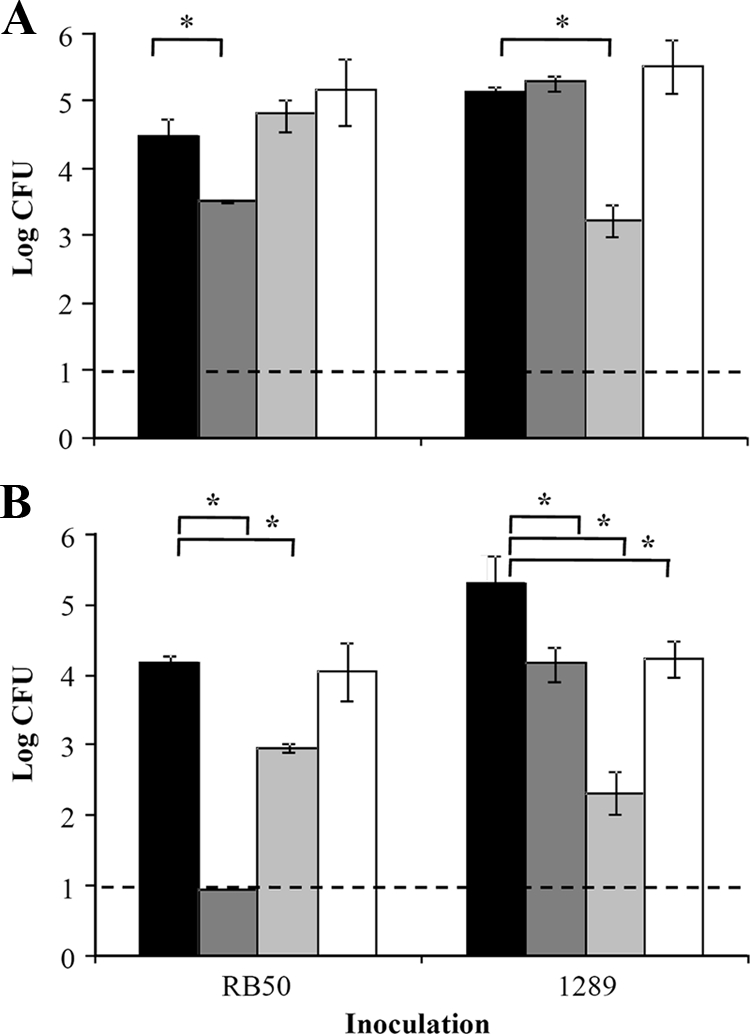

Since antibodies raised against one O-antigen type do not recognize the other type, we hypothesized that these two O-antigen serotypes would not be cross-protective in a murine infection model. To test this, groups of three mice were vaccinated with purified LPS from strain RB50, 1289 or RB50Δwbm or left unvaccinated and challenged 28 days later with either strain RB50 or 1289 (Fig. 5A). In naive mice, strains RB50 and 1289 grew to approximately 104.5 and 105.0 in the lower respiratory tract by 3 days postinoculation, respectively (Fig. 5A). In comparison, vaccination with RB50 LPS reduced the bacterial load of strain RB50 by approximately 10-fold (P = 0.021) (Fig. 5A). This relatively low level of protection is expected, considering this is an LPS-based vaccination regimen. In contrast to results with the vaccination with RB50 LPS, vaccination with 1289 or RB50Δwbm LPS did not lower the bacterial load of strain RB50 (P = 0.868 and 0.120, respectively) (Fig. 5A). Vaccination with 1289 LPS reduced the bacterial load of strain 1289 by approximately 100-fold in comparison to results for unvaccinated mice (P < 0.0001). Vaccination with RB50 or RB50Δwbm LPS did not lower the bacterial load of strain 1289 (P = 0.9983 and 0.6729, respectively) (Fig. 5A). Combined, these data indicate that the protective component of the LPS vaccine is the O antigen and LPS vaccines containing different O antigens do not induce cross-protection.

FIG. 5.

Effect of LPS vaccination and passive transfer of immune serum on numbers of B. bronchiseptica strains RB50, 1289, and RB50Δwbm. (A) C57BL/6 mice were either left unvaccinated (black) or vaccinated with LPS purified from strain RB50 (dark gray), 1289 (light gray), or RB50Δwbm (white). (B) C57BL/6 mice were given either naive serum (black) or RB50-induced (dark gray), 1289-induced (light gray), or RB50Δwbm-induced (white) serum and then inoculated with either strain RB50 or 1289. The bacterial load was quantified 3 days postinoculation. Numbers of bacteria are expressed as the average log CFU ± standard deviations. The dashed line represents the lower limit of detection. Asterisks denote P values of <0.05.

Since the antibody responses to each of these O antigens were poorly cross-reactive (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that there may be inefficient cross-immunity between strains. Using animals that had whole-cell vaccine- or infection-induced immunity, the level of cross-protection between strains RB50 and 1289 was examined. In these animals, tested at the height of the immune response, the lower respiratory tracts were fully protected against subsequent challenge with either strain (data not shown), indicating that a full memory response, consisting of both T- and B-cell immunity, against one strain is sufficient to protect against infection by a heterologous strain expressing a different O antigen. Since our Western and ELISA analyses indicated that the antibody response to strain RB50 was not completely cross-reactive to strain 1289 due to O-antigen variation and vice versa (Fig. 1 and 5A), we hypothesized that the O-antigen serotypes may contribute to inefficient cross-protective antibody responses. Therefore, naive, RB50-, 1289-, or RB50Δwbm-induced sera were collected 28 days postinoculation and transferred into naive mice, which were then inoculated with either strain RB50 or 1289 (Fig. 5B). By 3 days postinoculation, the bacterial numbers of strains RB50 and 1289 were 104.1 and 105.5 CFU in the lower respiratory tract of mice treated with naive sera (Fig. 5B). When mice received RB50-induced sera, the bacterial load of strain RB50 was near or below the limit of detection (10 CFU), a 1,000-fold reduction in comparison to results for mice treated with naive sera (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5B). In contrast to this high level of protection afforded by RB50-induced sera, 1289-induced sera decreased the load of RB50 by 10-fold (P < 0.0001), which indicates that 1289-specific antibodies did not provide as efficient protection against strain RB50 as RB50-induced antibodies (Fig. 5B). Transfer of RB50Δwbm-induced sera did not decrease the bacterial load of strain RB50 (P = 0.998), indicating that antibodies to O antigen are required for efficient antibody-mediated clearance of strain RB50 (Fig. 5B). When mice infected with strain 1289 received 1289-induced antibodies, a 1,000-fold decrease in the bacterial load was observed (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5B). In contrast to this high level of protection, RB50- and RB50Δwbm-induced sera decreased the load of strain 1289 by only 10-fold, which indicates that these antibodies did not provide protection as efficient as that of 1289-induced antibodies (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.006, respectively) (Fig. 5B) and shows that O-antigen-specific antibodies to the O1 serotype did not contribute to the clearance of strain 1289. Taken together, these data support the conclusion that the lack of cross-reactivity between O-antigen serotypes causes inefficient antibody-mediated clearance of B. bronchiseptica strains.

DISCUSSION

Using a large set of B. bronchiseptica strains, this study builds upon previous reports suggesting that B. bronchiseptica strains can produce one of two immunologically distinct O-antigen serotypes (Fig. 1 and 2) (30, 32, 35). We suggest the names O1 and O2 to describe the O-antigen serotypes that are cross-reactive with antibodies induced by strains RB50 and 1289, respectively. In all cases, the O1 and O2 serotypes were associated with the presence of the classical and alternative O-antigen loci, respectively (Fig. 3). The phylogenetic lineage of B. bronchiseptica strains does not appear to correlate with either of these O-antigen loci, which strongly suggests that they are horizontally transferred between strains (Fig. 4). This is the first evidence of horizontally transferred genes that encode an antigen in Bordetella. The induction of serotype-specific immunity contributes to inefficient cross-protective immunity between strains (Fig. 1 and 5). Together, our data are consistent with the idea that the O-antigen serotypes of B. bronchiseptica are encoded by separate, horizontally transferred O-antigen loci, which contributes to the inefficient cross-immunity between strains.

A previous study showed that the LPS-related genes of B. bronchiseptica isolates from complex I were less polymorphic than those belonging to complex IV, which includes strains that are more closely related to B. pertussis than other B. bronchiseptica strains (9). The majority of this variation was due to the lack of wbm genes in many complex IV strains (9). Consistent with this, we demonstrate that all complex I isolates examined contain either the classical or alternative locus while three complex IV isolates do not contain either the classical or alternative locus (Fig. 4). As with other complex IV strains, the most likely explanation for this is that these strains do not have genes encoding an O antigen. One exception to this general conclusion is strain MO149, which appeared to produce an O antigen in a previous study despite the absence of the classical and alternative O-antigen genes (9). When analyzed more closely, it was determined that this strain expresses an O antigen that is distinct from that of either O1 or O2 strains (E. Vinogradov and A. Preston, unpublished data). These data are consistent with the finding that this strain's O-antigen did not cross-react with sera containing antibodies to either O1 or O2 (data not shown). Sequencing of the wbm locus in strain MO149 indicates that it contains orthologs of wbmA to wbmD and homologs, with low levels of identity, to wbmF, wbmH to wbmK, and BB0121 (Vinogradov and Preston, unpublished).

The majority of strains that were PCR screened for the classical or alternative O-antigen loci were also screened for the expression of an O1 or O2 serotype (Fig. 3 and data not shown). While all strains expressing one of these serotypes contained one of the loci, not all strains containing one of these loci always expressed one of these serotypes. Two possibilities could lead to this result. First, it may be that these B. bronchiseptica strains lost expression of their O antigen, as has previously been observed to occur (13), potentially due to mutation of any of the genes required for its synthesis. The second possibility is that these strains express an antigenically distinct O-antigen serotype, assembly of which may or may not involve some or all of the genes detected in these assays. For example, the strain BPP5 (ST16) was observed to contain the alternative O-antigen locus but did not express either the O1 or O2 serotype. A previous study by Brinig et al. showed by CGH that the wbm locus of this strain contains most of the alternative O-antigen genes but with numerous differences in the wbmA-to-wbmN region (5). While 3 of 49 strains examined did not appear either to contain the O-antigen locus or to express either O-antigen serotype and 6 of 46 strains containing either O-antigen locus could not be serotyped, these “nontyped” strains still make up a minority of B. bronchiseptica strains. Thus, the O1 and O2 serotypes appear to dominate within B. bronchiseptica.

With some pathogens, O-antigen serotype has been shown to correlate with persistence of pathogens in a specific host species, a particular disease phenotype, or the virulence of strains as measured by 50% lethal dose in an infection model (18). In the case of B. bronchiseptica, a correlation between host species or virulence and O-antigen serotype does not appear to exist. Although we did not directly test if the O-antigen serotype caused a difference in virulence since the “serotype-specifying region” of the O antigen is large (∼9 kb) and difficult to swap between strains, we did not observe a relationship between the O-antigen serotype of strains and a particular level of virulence as measured by the 50% lethal dose in our murine model of infection. For example, we have described O2 strains that are of substantially greater (6a) or lesser (6) virulence than strain RB50, an O1 strain. Additionally, we did not observe a correlation between serotype and host species (data not shown). Therefore, the O-antigen serotype does not appear to correspond to a particular host species or virulence in the case of B. bronchiseptica.

Ecological theory predicts that that two closely related, immunizing pathogens cannot occupy the same host population if immunity is cross-protective (3). However, escape of immune-mediated competition can occur when there is antigenic diversity among pathogens, which can result in the maintenance of multiple, closely related pathogens in the same host population (11, 14, 15, 31). For example, strains with antigenically distinct O antigens cycle with the epidemic dynamics of cholera (21, 24). Similarly, it has been hypothesized that the four distinct O-antigen serotypes contribute to the coexistence of four typhoidal Salmonella strains (18). Evasion of B. pertussis-induced immunity by the O antigen of B. parapertussis potentially explains the coexistence of these two etiological agents of whooping cough in the human population (4, 41). While careful examination of the molecular epidemiology of B. bronchiseptica has not been completed to date (25), it is reasonable to speculate that the generation of O-antigen diversity via horizontal gene transfer between B. bronchiseptica strains may increase the ability of these bacteria to circulate within a given host population. Additionally, we speculate that avoidance of immune-mediated competition may represent one of the driving forces for maintaining two antigenically distinct O antigens among B. bronchiseptica strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Sanger Institute for access to unpublished genomic sequence of B. bronchiseptica strain 253. Thank you to all members of the Harvill laboratory for discussion and critical review of the manuscript and to Gráinne Long for assistance with statistical analysis. The mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI 053075, AI 065507, and GM083113 (to E.T.H.).

We have no conflicting financial interests.

Editor: R. P. Morrison

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 June 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, A., and D. Maskell. 1996. The identification, cloning and mutagenesis of a genetic locus required for lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Bordetella pertussis. Mol. Microbiol. 1937-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, A. G., R. M. Thomas, J. T. Cadisch, and D. J. Maskell. 1998. Molecular and functional analysis of the lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis locus wlb from Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Mol. Microbiol. 2927-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, R. M. 1995. Evolutionary pressures in the spread and persistence of infectious agents in vertebrate populations. Parasitology. 111(Suppl.)S15-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjornstad, O. N., and E. T. Harvill. 2005. Evolution and emergence of Bordetella in humans. Trends Microbiol. 13355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinig, M. M., C. A. Cummings, G. N. Sanden, P. Stefanelli, A. Lawrence, and D. A. Relman. 2006. Significant gene order and expression differences in Bordetella pertussis despite limited gene content variation. J. Bacteriol. 1882375-2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buboltz, A. M., T. L. Nicholson, M. R. Parette, S. E. Hester, J. Parkhill, and E. T. Harvill. 2008. Replacement of adenylate cyclase toxin in a lineage of Bordetella bronchiseptica. J. Bacteriol. 1905502-5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Buboltz, A. M., T. L. Nicholson, L. S. Weyrich, and E. T. Harvill. Role of the type III secretion system in a hypervirulent lineage of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect. Immun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Burns, V. C., E. J. Pishko, A. Preston, D. J. Maskell, and E. T. Harvill. 2003. Role of Bordetella O antigen in respiratory tract infection. Infect. Immun. 7186-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter, P. A., and J. F. Miller. 1994. BvgAS-mediated signal transduction: analysis of phase-locked regulatory mutants of Bordetella bronchiseptica in a rabbit model. Infect. Immun. 623381-3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diavatopoulos, D. A., C. A. Cummings, L. M. Schouls, M. M. Brinig, D. A. Relman, and F. R. Mooi. 2005. Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, evolved from a distinct, human-associated lineage of B. bronchiseptica. PLoS Pathog. 1e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goebel, E. M., D. N. Wolfe, K. Elder, S. Stibitz, and E. T. Harvill. 2008. O antigen protects Bordetella parapertussis from complement. Infect. Immun. 761774-1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gog, J. R., and B. T. Grenfell. 2002. Dynamics and selection of many-strain pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9917209-17214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Fraga, S., M. Pichel, N. Binsztein, J. A. Johnson, J. G. Morris, Jr., and O. C. Stine. 2008. Lateral gene transfer of O1 serogroup encoding genes of Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 28632-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gueirard, P., K. Le Blay, A. Le Coustumier, R. Chaby, and N. Guiso. 1998. Variation in Bordetella bronchiseptica lipopolysaccharide during human infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta, S., and R. M. Anderson. 1999. Population structure of pathogens: the role of immune selection. Parasitol. Today 15497-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta, S., and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Exploring the evolution of diversity in pathogen populations. Trends Microbiol. 9181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvill, E. T., A. Preston, P. A. Cotter, A. G. Allen, D. J. Maskell, and J. F. Miller. 2000. Multiple roles for Bordetella lipopolysaccharide molecules during respiratory tract infection. Infect. Immun. 686720-6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingsley, R. A., and A. J. Baumler. 2000. Host adaptation and the emergence of infectious disease: the Salmonella paradigm. Mol. Microbiol. 361006-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirimanjeswara, G. S., P. B. Mann, and E. T. Harvill. 2003. Role of antibodies in immunity to Bordetella infections. Infect. Immun. 711719-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirimanjeswara, G. S., P. B. Mann, M. Pilione, M. J. Kennett, and E. T. Harvill. 2005. The complex mechanism of antibody-mediated clearance of Bordetella from the lungs requires TLR4. J. Immunol. 1757504-7511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koelle, K., M. Pascual, and M. Yunus. 2006. Serotype cycles in cholera dynamics. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2732879-2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubler-Kielb, J., E. Vinogradov, G. Ben-Menachem, V. Pozsgay, J. B. Robbins, and R. Schneerson. 2008. Saccharide/protein conjugate vaccines for Bordetella species: preparation of saccharide, development of new conjugation procedures, and physico-chemical and immunological characterization of the conjugates. Vaccine 263587-3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longini, I. M., Jr., M. Yunus, K. Zaman, A. K. Siddique, R. B. Sack, and A. Nizam. 2002. Epidemic and endemic cholera trends over a 33-year period in Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 186246-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattoo, S., and J. D. Cherry. 2005. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18326-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooi, F. R., and E. M. Bik. 1997. The evolution of epidemic Vibrio cholerae strains. Trends Microbiol. 5161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray, G. L., S. R. Attridge, and R. Morona. 2006. Altering the length of the lipopolysaccharide O antigen has an impact on the interaction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with macrophages and complement. J. Bacteriol. 1882735-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myc, A., J. Buck, J. Gonin, B. Reynolds, U. Hammerling, and D. Emanuel. 1997. The level of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is significantly increased in plasma in patients with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4113-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholson, T. L. 2007. Construction and validation of a first-generation Bordetella bronchiseptica long-oligonucleotide microarray by transcriptional profiling the Bvg regulon. BMC Genomics 8-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Parkhill, J., M. Sebaihia, A. Preston, L. D. Murphy, N. Thomson, D. E. Harris, M. T. Holden, C. M. Churcher, S. D. Bentley, K. L. Mungall, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, L. Temple, K. James, B. Harris, M. A. Quail, M. Achtman, R. Atkin, S. Baker, D. Basham, N. Bason, I. Cherevach, T. Chillingworth, M. Collins, A. Cronin, P. Davis, J. Doggett, T. Feltwell, A. Goble, N. Hamlin, H. Hauser, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, S. Leather, S. Moule, H. Norberczak, S. O'Neil, D. Ormond, C. Price, E. Rabbinowitsch, S. Rutter, M. Sanders, D. Saunders, K. Seeger, S. Sharp, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, L. Unwin, S. Whitehead, B. G. Barrell, and D. J. Maskell. 2003. Comparative analysis of the genome sequences of Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Nat. Genet. 3532-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plotkin, J. B., J. Dushoff, and S. A. Levin. 2002. Hemagglutinin sequence clusters and the antigenic evolution of influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 996263-6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preston, A., A. G. Allen, J. Cadisch, R. Thomas, K. Stevens, C. M. Churcher, K. L. Badcock, J. Parkhill, B. Barrell, and D. J. Maskell. 1999. Genetic basis for lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biosynthesis in bordetellae. Infect. Immun. 673763-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preston, A., and D. Maskell. 2001. The molecular genetics and role in infection of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in the Bordetellae. J. Endotoxin Res. 7251-261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preston, A., J. Parkhill, and D. J. Maskell. 2004. The bordetellae: lessons from genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2379-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preston, A., B. O. Petersen, J. O. Duus, J. Kubler-Kielb, G. Ben-Menachem, J. Li, and E. Vinogradov. 2006. Complete structures of Bordetella bronchiseptica and Bordetella parapertussis lipopolysaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 28118135-18144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves, P. 1993. Evolution of Salmonella O antigen variation by interspecific gene transfer on a large scale. Trends Genet. 917-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeves, P. 1995. Role of O-antigen variation in the immune response. Trends Microbiol. 3381-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stenutz, R., A. Weintraub, and G. Widmalm. 2006. The structures of Escherichia coli O-polysaccharide antigens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30382-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 241596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinogradov, E., M. S. Peppler, and M. B. Perry. 2000. The structure of the nonreducing terminal groups in the O-specific polysaccharides from two strains of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Eur. J. Biochem. 2677230-7237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolfe, D. N., E. M. Goebel, O. N. Bjornstad, O. Restif, and E. T. Harvill. 2007. The O antigen enables Bordetella parapertussis to avoid Bordetella pertussis-induced immunity. Infect. Immun. 754972-4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfe, D. N., G. S. Kirimanjeswara, E. M. Goebel, and E. T. Harvill. 2007. Comparative role of immunoglobulin A in protective immunity against the bordetellae. Infect. Immun. 754416-4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.