Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important human pathogen that often carries temperate bacteriophages. As part of a program to characterize the genetic makeup of prophages associated with clinical strains and to assess the potential roles that they play in the biology and pathogenesis in their host, we performed comparative genomic analysis of 10 temperate pneumococcal phages. All of the genomes are organized into five major gene clusters: lysogeny, replication, packaging, morphogenesis, and lysis clusters. All of the phage particles observed showed a Siphoviridae morphology. The only genes that are well conserved in all the genomes studied are those involved in the integration and the lysis of the host in addition to two genes, of unknown function, within the replication module. We observed that a high percentage of the open reading frames contained no similarities to any sequences catalogued in public databases; however, genes that were homologous to known phage virulence genes, including the pblB gene of Streptococcus mitis and the vapE gene of Dichelobacter nodosus, were also identified. Interestingly, bioinformatic tools showed the presence of a toxin-antitoxin system in the phage φSpn_6, and this represents the first time that an addition system in a pneumophage has been identified. Collectively, the temperate pneumophages contain a diverse set of genes with various levels of similarity among them.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) is an important human pathogen and a major etiological agent of pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis in adults and of otitis media in children. The casualties due to the pneumococcus are estimated to be over 1.6 million deaths per year, and most of these deaths are of young children in developing countries (40). S. pneumoniae is also a human commensal that resides in the upper respiratory tract, and it is asymptomatically carried in the nasopharynx of up to 60% of the normal population (48).

Bacteriophages of S. pneumoniae (pneumophages) were first identified in 1975 from samples isolated from throat swabs of healthy children by two independent groups (46, 65). Since then, pneumophages have been identified from different sources and a variety of locations (44). The abundance of temperate bacteriophages in S. pneumoniae has been reported in different studies in the past (6, 54). Up to 76% of clinical isolates have been showed to contain prophages (or prophage remnants) when studied with a DNA probe specific for the major autolysin gene, lytA, which hybridizes with many of the endolysin genes of temperate pneumococcal phages (54). Hybridization analyses have identified highly similar prophages among pneumococcal clinical isolates even of different capsular serotypes, a result which indicates the widespread distribution of these mobile genetic elements among virulent strains (26).

Only three S. pneumoniae bacteriophage genomes have been characterized in detail, and their sequences have been determined. Dp-1 and Cp-1 are lytic bacteriophages, whereas MM1 is a temperate pneumophage (45, 50, 52). Genes coding for virulence factors such as toxins or secreted enzymes have been associated with the presence of prophages in both gram-negative (67) and gram-positive bacteria, such as Streptococcus pyogenes (7) and Staphylococcus aureus (23). Because a considerable number of toxin genes are located in prophages, phage dynamics are of apparent importance for bacterial pathogenesis. Unfortunately, the role of temperate bacteriophages in the virulence of S. pneumoniae remains mostly unknown.

Recently, the availability of relatively inexpensive next-generation sequencing technologies has permitted the complete genomic analysis of dozens of genomes of pneumococcal clinical isolates. In this report, we present a comparative genomic analysis of 10 pneumophages identified in the genomes of newly sequenced S. pneumoniae strains. The proteome of these phages has been predicted and annotated by comparative sequence analyses by using the available databases at the National Center for Biotechnological Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). This systematic characterization of pneumophage genomes provides for a substantial increase in our knowledge of the global proteome and the overall genetic diversity of this important human pathogen. The comparative analysis of multiple temperate bacteriophages from a single species offers a unique opportunity to study one of the mechanisms of lateral gene transfer that drive prokaryotic genetic diversity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and DNA isolation.

The S. pneumoniae temperate bacteriophages described in this study and their host strains are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown on blood agar base no. 2 (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) defibrinated horse blood (E & O Laboratories, Bonnybridge, United Kingdom) or in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid Ltd.). All incubations were kept static at 37°C. Clinical isolates were serotyped and analyzed by multilocus sequence typing (63) at the Scottish Meningococcus and Pneumococcus Reference Laboratory. DNA was isolated using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit by following the manufacturer's protocol with minor modifications. Minor modifications were included in the protocol to increase the final yield as follows. A total of 1.5 ml of an overnight culture was used to provide cell pellets; cells were lysed using a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA, 20 mg/ml lysozyme, and 1.2% Triton X-100; and DNA was eluted in a final volume of 150 μl.

TABLE 1.

Summary of genome sizes, gene contents, gene diversities, and proteome contents for S. pneumoniae prophages

| Prophage | Host strain (serotype) | Accession no.a | MLSTb | Genome size (bp) | % GC content | attc | Predicted genes | % Coding | No. of genes with unknown function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φSpn_OXC | OXC141d (3) | SI | 180 | 33,276 | 40.5 | OXC | 51 | 92.7 | 31 |

| φSpn_3 | CGSSp3BS71e (3) | NZ_AAZZ01000016 | 180 | 33,069 | 40.2 | OXC | 51 | 91.7 | 31 |

| φSpn_11 | CGSSp11BS70e (11) | NZ_ABAC01000015 | 62 | 31,071 | 40.5 | OXC | 53 | 94.7 | 38 |

| φSpn_14 | CGSSp14BS69e (14) | NZ_ABAD01000021 | 124 | 31,674 | 38.9 | OXC | 56f | 93.7 | 35 |

| φSpn_H_1 | Hungary19A-6 (19A) | CP000936 | 199 | 33,996 | 39.33 | OXC | 42 | 93.8 | 21 |

| φSpn_1873 | CDC1873-00 (6A) | NZ_ABFS01000005 | 376 | 34,448 | 39.29 | OXC | 42 | 96.5 | 19 |

| φSpn_3059 | CDC3059-06 (19A) | NZ_ABGG01000014 | 199 | 37,893 | 40.61 | OXC | 58 | 96.6 | 37 |

| φSpn_195_2 | SP195 (9V) | NZ_ABGE01000013 | 156 | 38,455 | 40.84 | OXC | 49 | 92.4 | 28 |

| φSpn_6 | CGSSp6BS73e (6A) | NZ_ABAA01000017 | 460 | 42,069 | 40.1 | MM1 | 62f | 91.2 | 43 |

| φSpn_9 | CGSSp9BS68e (9V) | ABAB00000000 | 1269 | 40,692 | 39.8 | MM1 | 59 | 87.7 | 41 |

| φSpn_19 | CGSSp19BS75e (19F) | ABAF00000000 | 485 | 39,477 | 39.8 | MM1 | 58 | 89.9 | 41 |

| φSpn_23 | CGSSp23BS72e (23F) | ABAG00000000 | 37 | 39,387 | 39.7 | MM1 | 66f | 89.7 | 50 |

| φSpn_195_1 | SP195 (9V) | NZ_ABGE01000002 | 156 | 41,058 | 39.92 | MM1 | 59 | 88.1 | 41 |

| φSpn_18 | CGSSp18BS74e (6B) | ABAE00000000 | ND | 37,362 | 38.2 | φSpn_18 | 53 | 93.3 | 29 |

| φSpn_H_2 | Hungary19A-6 (19A) | CP00936 | 199 | 40,079 | 39.4 | φSpn_18 | 52 | 96.1 | 25 |

| MM1g | 949 (23F) | AJ302074 | 81 | 40,248 | 38.4 | MM1 | 53 | 94.3 | 26 |

| MM1-1998g | DCC1808 (24) | DQ113772 | |||||||

| MM1-2008 | 23Fh (23F) | SI | 81 | 39,307 | 38.2 | MM1 | 53 | 94.7 | 26 |

SI, obtained from the Sanger Institute website (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_pneumoniae/).

MLST, multilocus sequence type; ND, not determined.

att, attachment core sequence; OXC, attOXC (SP_0019-SP_0020); MM1, attMM1 (SP_1563-SP_1564); φSpn_18, attφSpn_18 (SP_0020-SP_0021).

Provided by A. Brueggemann (University of Oxford, United Kingdom).

Provided by Allegheny General Hospital, Allegheny-Singer Research Institute, Center for Genomic Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA (30).

Calculation of the gene number may vary due to the annotation of the pblB gene.

The data for MM1 and MM1-1998 have been previously reported (50).

Provided by the Scottish Meningococcus and Pneumococcus Reference Laboratory (Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow, United Kingdom).

Phage preparation and electron microscopy.

Crude preparations of bacteriophages were obtained following mitomycin C induction of lysogenic strains. Each strain culture was grown for 8 h in brain heart infusion broth and then diluted 1:100 in fresh medium. When the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1 to 0.25, mitomycin C was added to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. The culture was then incubated at 37°C until lysis was observed. The lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 3,300 × g at 4°C by using an N11150 rotor in a Sigma 4K15 centrifuge. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 110,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C using a 70 Ti rotor in a Beckman Coulter Optima LE-80K ultracentrifuge. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of ammonium acetate (0.1 M, pH 7.2).

Phage preparations were negatively stained with the NanoVan (methylamine vanadate; Nanoprobes) staining solution on carbon-reinforced, Formvar-coated copper grids (300 mesh) as described previously (37) with minor modifications. Minor modifications consisted of impregnating the grid with 5 μl of the phage sample and leaving it for 1 min. Afterwards, 5 μl of the stain was placed on the grid for 1 min and washed with the same volume of water for 1 min. The grids were dried at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were observed using a Zeiss LEO 902 electron microscope working at 80 kV. Phage DNA was purified from crude extracts of strain CGSSp6BS73. Briefly, the pellet obtained from the lysate after mitomycin C induction was resuspended in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) and treated with DNase I (1 mg/ml). Then, it was treated with 50 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 100 μg/ml proteinase K for 2 h at 37°C. Finally, DNA was isolated following phenol-chloroform steps and resuspended in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]).

Bioinformatic methods and cluster analysis.

Prophage genomes were obtained from the sequence of their host (Table 1) followed by confirmation by restriction digest (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Gene prediction, annotation, and sequence clustering were performed using Glimmer 3.0 (14), Artemis (57), and TribeMCL (22), respectively. Genome comparisons were generated using BLAST algorithms and analyzed using the Artemis Comparison Tool (13). The criteria used to identify putative open reading frames (ORFs) were the presence of (i) the potential to code for a polypeptide of more than 33 amino acid (aa) residues and (ii) a putative ribosome binding site (2) and, at 3 to 9 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the central G of the ribosome binding site (31), an ATG, GTG, or TTG codon that could serve as a start codon. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with Phylip Neighbor (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html) and visualized with TreeView X (http://darwin.zoology.gla.ac.uk/∼rpage/treeviewx/). The dot matrix was calculated using Dotter with a sliding window of 25 bp (62). Identity values for nucleotide comparison were obtained using the Artemis Comparison Tool (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/ACT/). Prediction of transmembrane helices in proteins and of signal peptides were carried out using the TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) and SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) servers, respectively.

In certain cases for the phage genomes, the sequences were incomplete due to gaps in the assembly. PCR gap closure was performed as described previously (29), by sequencing PCR amplicons targeted to fill gaps between neighboring contigs. Gaps were inferred by scaffolding to all sequenced S. pneumoniae genomes using Nucmer, and primers were designed for the ends of the contigs. A PCR was run with a 7-min extension period, and PCR products were sequenced using Sanger sequencing. The primers designed for gap amplification, as well as additional primers designed within the gap based on scaffolding information, were also used as sequencing primers. If primers designed within the inferred gaps were not successful, primer walk sequencing was employed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General features of S. pneumoniae phage particles and their genomes.

Mitomycin C lysates of lysogenic strains OXC141, CGSSp3BS71, CGSSp6BS73, CGSSp9BS68, CGSSp11BS70, CGSSp14BS69, CGSSp18BS74, CGSSp19BS75, CGSSp23BS72, and 23F were observed with an electron microscope. With the exceptions of strain CGSSp23BS68, in which only capsids could be seen, and CGSSp9BS72, in which no phage-like particles could be identified, phage particles showing a Siphoviridae morphology were observed in most preparations (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The sizes of the tails and heads observed were homogeneous (approximately 50 by 50 nm for the heads and 200 nm for the tails).

The complete genomes of 10 double-stranded-DNA S. pneumoniae temperate bacteriophages (φSpn_OXC, φSpn_3, φSpn_6, φSpn_9, φSpn_11, φSpn_14, φSpn_18, φSpn_19, φSpn_23, and MM1-2008) were sequenced and/or analyzed using bioinformatic tools (see above) and compared to those of MM1 and MM1-1998, two closely related pneumophages that have been previously characterized (50). Combined sequence analysis of the phage genomes showed that they range from 31 to 42 kb in size and have an average GC content of 39.5% (Table 1), which is similar to the 39.7% GC content reported for the S. pneumoniae genome (64). Comparative analyses have revealed that the genomes of φSpn_OXC and φSpn_3 showed 98.6% identity (hereafter, they are referred to as φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3 bacteriophage). Similarly, since more than 99% identity has been found among the prophage from the 23F strain (MM1-2008) and the genomes of the temperate bacteriophages MM1 (50) and MM1-1998 (43), unless stated otherwise, these three phages are referred to collectively as MM1-like.

The majority of the ORFs carried by temperate pneumophages are transcribed from one strand, although the lysogeny module is usually transcribed from the opposite strand (see Table S1 to S9 in the supplemental material).

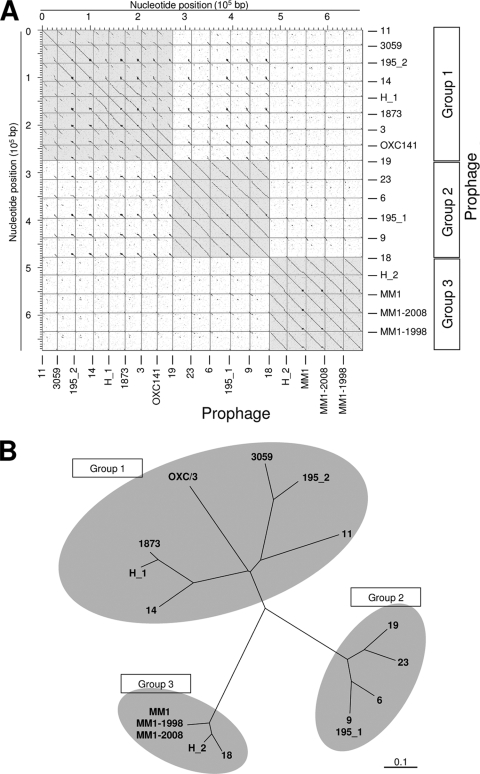

The 10 pneumophages studied here were grouped into three classes based on comparisons of the complete prophages (Fig. 1A) as well as their predicted encoded proteins (Fig. 1B): group 1, containing φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3, φSpn_11, and φSpn_14; group 2, including φSpn_6, φSpn_9, φSpn_19, and φSpn_23; and group 3, with MM1-2008 and φSpn_18. The sizes of the genomes vary slightly, with group 1 phages having genomes between 31 to 33 kb, group 2 phages having genomes from 39 to 42 kb, and group 3 phages having genomes from 37 to 40 kb (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Groups of pneumococcal prophages identified by genome comparisons. For brevity, the prefix “φSpn_” of phage names has been omitted. (A) Dot slot matrix calculated for the genome sequences of the S. pneumoniae prophages. The dot matrix was calculated using Dotter (62). (B) Unrooted tree based on the phage's predicted protein coding sequences. Sequences were clustered with TribeMCL using an E value cutoff of 10−30, and the tree was generated using similarity coefficients calculated between each phage pair on the basis of shared clusters.

As reported for other phage genomes, the predicted phage genes are not randomly distributed but organized in functional clusters (9). Each genome contains five different clusters: lysogeny, replication, packaging, morphology, and lysis clusters. This modular organization and order is shared with the previously studied pneumophages (44), although the lysogeny cluster is not present in the two lytic pneumophages, i.e., Cp-1 and Dp-1. However, genomes of S. pneumoniae temperate bacteriophages do not represent a homogeneous group; as already observed for prophages from dairy bacteria (17), important differences in the genetic modules have been identified (Table 2; see below).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the main characteristics identified in the genetic modules in the three different groups of temperate bacteriophages

| Phage group | Cluster members | Lysogeny module

|

Replication module

|

No. of genes for packaging module | Morphology module

|

Lysis module

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of genes | Integrase | No. of genes | Peculiarity(ies)a | No. of genes | Peculiarity(ies)b | No. of genes | Peculiarity(ies) | |||

| 1 | φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3 | 12 | Int1 | 16 | cg1 | 4 | 15 | Sfi21-like genus; pblB-like | 4 | Holin 1, holin 2 |

| φSpn_11 | 8 | Int1 | 22 | cg1, cg2 | 5 | 14 | Sfi11-like genus; pblAB-like | 4 | Holin 1, holin 2 | |

| φSpn_14 | 12 | Int1 | 20 | cg1, cg2 | 3 | 17 | Sfi21-like genus; pblB-like | 4 | Holin 1, holin 2 | |

| 2 | φSpn_6 | 7 | Int2 | 27 | cg1, cg2; TA system; vapE-like gene | 3 | 21 | Sfi11-like genus; pblB-like | 4 | Holin 1-holin 2 |

| φSpn_9 | 8 | Int2 | 25 | cg1, cg2; vapE-like gene | 3 | 20 | Sfi11-like genus; pblB-like | 4 | Holin 1 | |

| φSpn_19 | 7 | Int2 | 25 | cg1, cg2; vapE-like gene | 3 | 19 | Sfi11-like genus; pblB-like | 4 | Holin 1 | |

| φSpn_23 | 8 | Int2 | 30 | cg2; vapE-like gene | 3 | 21 | Sfi11-like genus; pblB-like | 4 | Holin 1, holin 2 | |

| 3 | MM1-2008 | 5 | Int2 | 24 | cg1, cg2; C5-MTase (α and β subunits) | 3 | 17 | Sfi11-like genus | 4 | Holin 1, holin 2 |

| φSpn_18 | 7 | Int3 | 22 | cg1, cg2; C5-MTase | 3 | 17 | Sfi11-like genus | 4 | Holin 1, holin 2 | |

cg, conserved genes identified in the replication module. TA system, toxin/antitoxin system (MazEF-like).

Sfi21/Sfi11-like genus indicate the genus of Siphoviridae phages as previously proposed (10).

Lysogeny module.

There are functional constraints that act to ensure the lysogeny module in temperate bacteriophages, as has been previously shown among Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages (49). Sequence analysis of the lysogenic modules of the pneumophage genomes revealed a similar organization. Despite different evolutionary origins, genes encoding integrases, transcriptional regulators belonging to Cro/cI families, and antirepressors have been identified in every lysogeny cluster analyzed.

Phage integrases are responsible for the integration of the phage genome into the bacterial chromosome. The putative integrases that are encoded by the temperate bacteriophages analyzed in this study belong to the integrase family of tyrosine recombinases (Int family). The Int family of integrases, such as the λ integrase, utilize a catalytic tyrosine to mediate strand cleavage and require other proteins encoded by the phage or the host bacteria (27). In addition to the catalytic tyrosine, five other residues are highly conserved in the tyrosine recombinase family, i.e., the RKHRH pentad (27). With the notable exception of the integrases encoded by MM1-like prophages, the putative integrases identified in the temperate pneumococcal bacteriophages clustered in the same three phage groups described above. Interestingly, the integrases encoded by MM1-like prophages were more similar to those of group 2 phages (Fig. 1A) than to that of φSpn_18 (see below). Predicted integrases encoded by φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3, φSpn_11, and φSpn_14 are highly related (group 1). They all have 382 aa, with the only exception being that encoded in the φSpn_14 genome, which has a size of 360 aa due to a frameshift. All alleged integrases of group 2 are identical in length, 375 aa, with alignment showing only five mismatches over the entire sequence. However, similarities between the group 2 and group 3 integrases have been identified only in the N-terminal part of the amino acid sequence. The first 51 aa residues are almost identical to those in this group of integrases, but the rest of the sequence is more divergent. In agreement with the characterization of integrases from the Int family (27), an amino acid comparison of group 2 integrases showed that the identity of the first 51 aa residues could be related to the capacity of binding to the DNA, whereas the recognition of the core region and the catalytic activity would be in the C-terminal part of the integrase protein.

Phages φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3, φSpn_11, and φSpn_14 are found integrated into their host strains between genes SP_0019 and SP_0020 in the TIGR4 genome (64). The att core sequence was identified by the alignment of the attL, attR of φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3, and the regions downstream and upstream of the cited genes in TIGR4. An overlapping region of 21 nt was identified as the att core region (attOXC) (5′-CTTTTTCATAATAATCTCCCT-3′). Two additional attOXC sequences are present in the TIGR4 genomes, i.e., between genes SP_0257 and SP_0258 and between genes SP_0260 and SP_0261. Phages φSpn_6, φSpn_9, φSpn_19, φSpn_23, and MM1/MM1-2008 are integrated at the same host genomic site as phage MM1 is inserted into strain Spain-23F1, that is, between genes SP_1563 and SP_1564 of the TIGR4 genome (26). The att core region in this case, or attMM1, is a 15-nt sequence (5′-TTATAATTCATCCGC-3′), and it is present only once in the TIGR4 genome (26). Phage φSpn_18 is inserted between genes SP_0020 and SP_0021. The att core region has not been identified, but genome comparisons (not shown) indicated that a remnant phage is located at the same position in a serotype 23F strain sequenced at the Sanger Institute.

The sequence analysis of the lysogeny modules of the pneumophages has revealed that the theory of modular evolution of bacteriophages cannot explain the diversity in gene content observed in this region (9). This theory suggests that the product of evolution is not a given virus but a family of interchangeable genetic elements (modules), each of which is multigenic and can be considered as a functional unit; exchange of a given module for another functionally equivalent module occurs by recombination among viruses belonging to the same interbreeding population. In contrast, as was previously suggested for phages from S. thermophilus (49) and other dairy bacteria (16), the unit for evolutionary exchange in S. pneumoniae bacteriophages is not a group of functional genes but could be as small as a single gene. A clear example is found in the lysogeny modules of S. pneumoniae group 1 phages, which are highly related but among which the putative exonuclease encoded by orf2 in φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3 and φSpn_14 has been replaced in the genome of φSpn_11 by a gene with a different origin and that encodes a hypothetical protein. Similarly, sequence analysis of lysogeny modules of group 2 and 3 pneumophages have revealed variation in gene content in the ORF immediately downstream of the integrase gene and genes located between the transcriptional regulator and the antirepressor (see Table S1 to S9 in the supplemental material). The sequence comparison of lysogenic modules showed that horizontal genetic exchange, besides point mutations, small deletions, and insertions that have also been identified, plays an important role in gene variation in S. pneumoniae bacteriophages.

Replication module.

The replication module is located adjacent to the lysogeny module in the genomes of all temperate bacteriophages studied and is highly conserved within each of the phage groups identified in this study; however, differences in the 3′-terminal flanking region were observed. Although replication modules between groups do not share remarkable similarities, the dot plot matrix (Fig. 1A) showed a conserved region in this module for all genomes studied. The region contains one conserved gene, cg1 or cg2 (conserved gene 1 or 2) (in φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3 and φSpn_23), or the two conserved genes (cg1 and cg2) (in all the rest of the phages), which encoded highly related gene products with unknown functions. These pairs of genes are the orf24 genes in φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3, orf20-orf21 in φSpn_11, orf25-orf26 in φSpn_14, orf29-orf30 in φSpn_6, orf30-orf31 in φSpn_9, orf28-orf29 in φSpn_19, orf31 (cg1) in φSpn_23, orf22-orf23 in MM1 and MM1-2008, and orf25-orf26 in φSpn_18. The product of the first of these two genes, absent only in φSpn_23, represents a protein with a size that ranged from 104 to 109 aa. These proteins showed 75.2% identity to each other. In contrast, the gene downstream is less conserved and absent only in φSpn_OXC/φSpn_3. The corresponding gene products are predicted to vary from 141 to 231 aa, with only 14.5% identity, mainly located at the C terminus. In any case, the location of these genes at the 3′-terminal flanking region of the replication module, and the high similarity shared between them make these sequences good candidates for locations where modular recombination can take place.

In the replication module of group 2 phages (φSpn_6, φSpn_9, φSpn_19, and φSpn_23) located immediately downstream of the gene encoding the replication protein, there is a gene encoding a protein showing a conserved virulence-associated domain (VirE or VapE) (see Tables S1 to S9 in the supplemental material). The proteins encoded in this position showed 96.2% amino acid identity among them, and their consensus sequence showed a 29% amino acid identity (E value, 10−34; identity, 104/353 bases) with the virulence-associated protein E (VapE) of Dichelobacter nodosus, in which this domain was originally identified (36). vapE is part of the vap regions of D. nodosus that have been associated with virulence (8). The mechanism of VapE in the virulence of D. nodosus has not been determined yet, but the presence of an integrase gene, showing similarities to integrase genes of Shigella flexneri phage Sf6 and coliphages P4 and φR7 located immediately upstream of vapE, suggested a role for bacteriophages in the evolution and transfer of these bacterial virulence determinants (13). Moreover, a vapE-like gene has also been identified in a pathogenicity island of S. aureus that also contains the toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (tst) gene (41) and in phages of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, although no role was determined for their presence (58). The role of vapE-like genes in the virulence of S. pneumoniae remains to be clarified. However, the proximity of vapE-like genes to cg1 and cg2 in the genome of group 2 bacteriophages suggests the possibility of exchange of this putative virulence factor with other bacteriophages.

The module of replication in the genome of φSpn_6 contains two genes located downstream of cg1 and cg2 which are on the complementary strand (orf32 and orf33). Sequence comparisons have revealed that this pair of genes may encode a toxin-antitoxin system (TA) similar to the MazEF system identified in Escherichia coli (1). Bacterial TA systems generally consist of a toxic protein and the cognate antidote (or antitoxin) that is proteolytically unstable (25, 69). The TA cassettes have a characteristic organization in which the gene for the antitoxin component precedes the toxin gene, which usually overlaps the last nucleotides of the antitoxin gene. TA gene pairs function to ensure plasmid maintenance after cell replication by eliminating plasmid-free cells that emerge as a result of segregation or replication defects. Chromosomal homologues of TA genes are widely distributed in bacteria and induce reversible cell cycle arrest or programmed cell death in response to starvation or other adverse conditions (28). TA systems have also been identified in E. coli temperate bacteriophages P1 and N15. P1 and N15 are temperate bacteriophages that are stably maintained as a circular plasmid and as a linear plasmid, respectively. The genes phd (standing for “prevent host death”) and doc (“death on cure”) are those encoding, respectively, the antitoxin and the toxin in bacteriophage P1 (38). The bacteriophage N15 encodes a TA system homologous to the tad-ata module of the Paracoccus aminophilus plasmid pAMI2 (18). Conserved TA domains homologous to the MazEF system of E. coli (1) in the protein products of genes orf32 and orf33 located in the replication module of phage φSpn_6 were predicted using RASTA-Bacteria, an online tool available for the identification of TA loci in prokaryotes (59). Homologous genes have been identified in a defective prophage present in strain CGSSp14BS69, φSpn_14.2, and in EJ-1, a mosaic bacteriophage of Streptococcus mitis (56). The putative antitoxin is encoded by the gene located upstream of the putative toxin gene. The mazE-like gene products identified in φSpn_6, φSpn_14.2, and EJ-1 are 95 aa in length and show 73.7% identity. The RASTA-Bacteria tool showed that the products of the mazE-like genes identified in the prophage genomes showed 34 to 36% identity (E value, 10−5) with the MazE conserved domain of E. coli (COG2336). The mazE-like gene in φSpn_6, φSpn_14.2, and EJ-1, as previously demonstrated in the MazEF system in E. coli (1, 20), overlaps the mazF-like gene. The mazF-like products are 117 aa long in φSpn_14.2 and φSpn_6 but are 73 aa long in EJ-1. The pneumophage mazF-like genes showed 38.5% identity among the group, and the RASTA-Bacteria tool showed 31% identity between the products of mazF-like genes of φSpn_6 and φSpn_14.2 and the conserved domain of MazF of E. coli (COG 2337) (E value, 10−15) and 40% identity in the case of the putative toxin MazF-like of phage EJ-1 (E value, 10−15). mazEF is a stress-induced “suicide module” that triggers cell death in E. coli when a stress condition interrupts the expression of mazE. This leaves MazF unimpeded to exert its toxic effect and causes cell death (19, 21). Recently, a mazE and pemK TA system has also been identified in the defective prophage LJ771 of Lactobacillus johnsonii (15). This TA cassette is located between the phage endolysin gene and the attR of LJ771, in which phage-encoded virulence factors in other streptococcal species have been identified (32, 33). mazE and pemK were cloned singly or together in E. coli, and their expression was studied during in vitro growth of the L. johnsonii lysogenic strain. This study concludes that the TA cassette identified in L. johnsonii behaves as a typical “addiction system” (15). The role of the MazEF system in S. pneumoniae bacteriophages has not been ascertained. It may function as a mechanism for the maintenance of the temperate bacteriophage in the chromosome of the host as previously observed in the TA systems in E. coli bacteriophages (38). Besides, it may have a putative physiological function, as shown by a recent study that describes a homologous MazEF system in the chromosome of Streptococcus mutans which showed similarities with the TA system identified in the pneumophages (39). The genes located upstream and downstream of the TA genes in φSpn_6 show high similarities to those from other pneumophages, so they may allow recombination at this locus.

Overall, group 3 bacteriophages (MM1, MM1-2008, and φSpn_18) are highly related, but in their replication modules, differences in gene content were identified. orf13 and orf14, identified in phage MM1, correspond to overlapping genes that are predicted to encode two components of a five-cytosine-specific DNA methyltransferase (C5-MTase) (50) that have been replaced in φSpn_18 by a gene identical to that encoding a C5-MTase in the temperate pneumophage VO1 (51). DNA methyltransferases appear to provide functions that are also beneficial to the host cell and usually are found as part of restriction-modification (R-M) systems (30). Recent studies on R-M systems have shown that these genes are among the most rapidly evolving and that their variation may have an effect on the fitness of the host (3). Variability affecting the presence or absence of C5-MTase in MM1-like bacteriophages confirms previous information suggesting that variation in R-M systems may also occur through selection acting on laterally transferred genes (35, 51).

Packaging module.

The majority of the packaging modules in the phage genomes studied here are essentially composed of three genes encoding the small and large subunits of the terminase and the portal protein, although in a few cases, the terminase is encoded by a single gene (see Table S1 to S9 in the supplemental material). Terminases are responsible for the recognition of their phage DNAs, ATP-dependent cleavage of the DNA concatemer, and packaging of the DNA molecules into the empty capsid shells through the portal protein (34). Genes encoding the putative terminase components were observed for all pneumophage genomes in this study, although the individual genes all predicted to fulfill the same functions appeared to have different origins. The packaging module of φSpn_11 represents the only exception, as a putative structural protein encoded by a gene located upstream of the terminase gene has been identified. This gene organization coincides with the ones previously described for the S. mitis prophage SM1 and the lactococcal r1t bacteriophage (61). Sequence comparison of packaging modules in group 2 phages showed that horizontal gene exchange can play a role in module variation. This is represented by the gene encoding the terminase small subunit of φSpn_23, which showed an origin different from that of the ones in the phages of the same group (Fig. 1A; see the supplemental material).

Morphology module.

Most of the differences found in the genomes of the group 1 phages are located within the morphology cluster; however, with the exception of φSpn_11, they appear to be similar to the Sfi21-like Siphoviridae phages (10). In contrast, the genome organizations of the morphology module of phage φSpn_11 and phages in group 2 and group 3 resemble that of the Sfi11-like phage group. The gene organization observed in the morphology module of φSpn_11 resembles homologous genes in the SM1 bacteriophage and in the lactococcal phage r1t, while others in this family maintain their capsid genes as a cluster located downstream of the terminase gene (17, 61, 66).

SM1 is a bacteriophage of S. mitis that was indirectly identified in the search for genetic loci mediating binding of the bacterium to human platelets (4, 5, 61). PblA and PblB are two surface-expressed proteins that are involved in the platelet binding activity of S. mitis but are, in fact, the tape measure protein and a tail fiber of the SM1 bacteriophage. pblA and pblB form part of the same operon, and mutations made in each of the genes have shown that the expression of both genes is required for the adhesion to human platelets of S. mitis SF100 in vitro (4) and for its virulence in an animal model of infective endocarditis (47). PblA and PblB function as adhesins and are expressed and liberated at the cell surface due to the activity of the holin and endolysin of SM1 in S. mitis SF100 (47). Similarities throughout the genomes of φSpn_11 and SM1 have been identified. Interestingly, an operon including pblA- and pblB-like genes has been identified in the morphology module of φSpn_11 (not shown). The amino acid sequences of PblA from SM1 and φSpn_11 showed 58.7% identity. There is an additional gene located between pblA and pblB, with an unknown function, in the genome of SM1. At the same position in the genome of phage φSpn_11, a homologous gene (with 63.4% identity to the gene in SM1) was identified. A PblB-like protein is also encoded by the φSpn_11 genome and, interestingly, by the genomes of all the group 1 and group 2 phages but not by MM1-like phages. The predicted products of pblB-like genes are greater than 1,000 aa in length, contain long repeats, and possess C termini that are rich in aromatic amino acids. The tryptophan-rich repeats observed at the C-terminal ends of PblA in SM1 and PblA-like protein in φSpn_11 appear to be responsible for binding to the cell wall (47) in a similar way to the choline-binding repeats characteristic of the S. pneumoniae major autolytic enzyme, LytA (24), and other choline-binding proteins (44). The function of pblA and pblB-like genes encoded by S. pneumoniae bacteriophages is unknown, but it is conceivable that they may play a role in adhesion. Nevertheless, this assumption needs to receive experimental support.

Lysis module.

The essential functions of the lysis module of temperate bacteriophages are usually performed by the products of the holin and endolysin genes. The holins are small molecules that accumulate in the membrane and at a specific time form holes that permeabilize it, whereas the endolysin molecules accumulate at the cytosol until the holes are formed so they can reach the cell wall (68). In many streptococcal phages, an unusual holin/endolysin arrangement that is characterized by two holin-like coding sequences that are located immediately upstream of the endolysin gene has been observed (11, 50, 60). This arrangement was also observed in the majority of the lysis modules studied here, as two holin-like sequences (hol1 and hol2) have been identified upstream of the endolysin gene. The exceptions are represented by phages φSpn_9 and φSpn_19, which have only one holin gene (hol2). hol1 genes encode highly related proteins (138 aa) showing 92% identity, whereas hol2 genes encode proteins of 110 or 111 aa, with 72% identity. Holins have been grouped into three classes according to the number of potential transmembrane domains. Class I members have the potential to form three transmembrane domains, and class II members can form only two transmembrane domains. The third class of holins comprises atypical or unclassified holins (68). Hol1 proteins belong to class I holins, as they have the potential to form three transmembrane domains, while hol2 gene products showed only one transmembrane domain (from Ile7 to Val24). This region in Hol2 proteins might also correspond to a cleavage signal sequence with a potential signal processing site located between Ala26 and Val27, as predicted by bioinformatic analysis (not shown). Similar features have been described for the RI protein, the bacteriophage T4 antiholin (53). Consequently, the hol2 gene products are most probably antiholins.

All the temperate bacteriophages, except φSpn_18, harbor typical lytA-like alleles, as they all encode products the same size as the major pneumococcal autolysin, LytA (318 aa) (42). It is noteworthy that the N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidases encoded by the temperate pneumophages studied here share a high degree of similarity among one another (91.5%) and with the host LytA enzyme (68.3% identity). The presence of lytA-like alleles in all the genome studies here suggests that LytA-like amidases are the most abundant endolysins from temperate pneumophages and strongly suggests that recombination exchange between the endolysin-encoding gene of the prophage and the host gene lytA participates in the evolution of these genes.

New bacteriophages identified in additional S. pneumoniae strains sequenced by the J. Craig Venter Institute.

While this work was in preparation, the genomes of seven additional S. pneumoniae strains were sequenced at the J. Craig Venter Institute, and the data became available online. Temperate bacteriophages have been found in four of those genomes: those of SP195, CDC3059-06, Hungary19A-6, and CDC1873-00. The newly identified prophages presented the same modular organization as already described for pneumophages and showed different degrees of similarity between them. Interestingly, the new phage genomes grouped perfectly well with the pneumophage genomes studied in this work and share the same intrinsic peculiarities described in this report for each of the groups (Fig. 1). Notably, the genomes of two bacteriophages have been identified in the sequence of strains SP195 (φSpn_195_1 and φSpn_195_2) and Hungary19A-6 (φSpn_H_1 and φSpn_H_2). Phage φSpn_195_1 is inserted into attMM1 and was shown to be highly related to φSpn_9 and other group 2 phages, whereas φSpn_195_2, which integrates into attOXC, was related to group 1 phages (Fig. 1). The genome of the strain Hungary19A-6 also contained two bacteriophages: φSpn_H_1, inserted into attOXC, and φSpn_H_2, inserted into attφSpn_18. It is noteworthy that the gene encoding the φSpn_H_2 endolysin is truncated, indicating that this phage is defective and depends on the endolysin encoded by φSpn_H_1 and/or on the host LytA N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase for the liberation of its progeny. The phages identified in the genomes of strains CDC3059-06 and CDC1873-00 are both inserted in attOXC and belong to group 1 phages (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, conserved genes cg1 and cg2 as well as putative virulence factors like vapE-like and pblB-like genes are also present in the prophages identified in this group of strains.

Conclusions.

The main objective of this study was to compare and analyze the sequences of 10 temperate bacteriophages of S. pneumoniae. The presence of temperate bacteriophages in pneumococcal isolates is quite high, but their genetic contents have not yet been well characterized. Our analysis suggested that the genomes of temperate pneumophages can be placed into groups but that there is intergroup recombination that takes place as well as horizontal gene exchanges between phage populations within a group. The remarkable number of genes encoding proteins with no similarities to annotated proteins showed the potential for identifying novel products of biological importance. Moreover, the genome analysis performed in this study has provided us with the knowledge to design a novel method for the detection and identification of temperate bacteriophages in clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae as recently described (55). In addition and most importantly, the sequences of new bacteriophage genomes will help to ascertain the implication of temperate bacteriophages in the virulence of S. pneumoniae.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to P. Garcia and H. Tettelin for helpful comments and the critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank M. Mullin and L. Tetley for skillful assistance at the electron microscopy facilities at the University of Glasgow. We thank D. Aanensen of Imperial College for help with sequence-based clustering of phage sequences. We acknowledge the use of core facilities at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. The sequence data for the S. pneumoniae strains Spain23F-1 and OXC141 were produced by the S. pneumoniae Sequencing Group at the Sanger Institute and can be obtained from http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_pneumoniae.

P. Romero is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia (EX-2006-0759). This work was supported by a grant from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (SAF2006-00390) and by grants DC05659, DC04173, and DC02148 from the U.S. NIH NIDCD. CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CibeRes) is an initiative of ISCIII.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 June 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizenman, E., H. Engelberg-Kulka, and G. Glaser. 1996. An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 936059-6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacot, C. M., and R. H. Reeves. 1991. Novel tRNA gene organization in the 16S-23S intergenic spacer of the Streptococcus pneumoniae rRNA gene cluster. J. Bacteriol. 1734234-4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayliss, C. D., M. J. Callaghan, and E. R. Moxon. 2006. High allelic diversity in the methyltransferase gene of a phase variable type III restriction-modification system has implications for the fitness of Haemophilus influenzae. Nucleic Acids Res. 344046-4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensing, B. A., C. E. Rubens, and P. M. Sullam. 2001. Genetic loci of Streptococcus mitis that mediate binding to human platelets. Infect. Immun. 691373-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensing, B. A., I. R. Siboo, and P. M. Sullam. 2001. Proteins PblA and PblB of Streptococcus mitis, which promote binding to human platelets, are encoded within a lysogenic bacteriophage. Infect. Immun. 696186-6192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernheimer, H. P. 1977. Lysogeny in pneumococci freshly isolated from man. Science 19566-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisno, A. L., M. O. Brito, and C. M. Collins. 2003. Molecular basis of group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloomfield, G. A., G. Whittle, M. B. McDonagh, M. E. Katz, and B. F. Cheetham. 1997. Analysis of sequences flanking the vap regions of Dichelobacter nodosus: evidence for multiple integration events, a killer system, and a new genetic element. Microbiology 143553-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botstein, D. 1980. A theory of modular evolution for bacteriophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 354484-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brüssow, H., and F. Desiere. 2001. Comparative phage genomics and the evolution of Siphoviridae: insights from dairy phages. Mol. Microbiol. 39213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruttin, A., F. Desiere, S. Lucchini, S. Foley, and H. Brüsow. 1997. Characterization of the lysogeny module from the temperate Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage φSfi21. Virology 233136-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carver, T. J., K. M. Rutherford, M. Berriman, M. A. Rajandream, B. G. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2005. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 213422-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheetham, B. F., and M. E. Katz. 1995. A role for bacteriophages in the evolution and transfer of bacterial virulence determinants. Mol. Microbiol. 18201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delcher, A. L., K. A. Bratke, E. C. Powers, and S. L. Salzberg. 2007. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 23673-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denou, E., R. D. Pridmore, M. Ventura, A.-C. Pittet, M.-C. Zwahlen, B. Berger, C. Barretto, J.-M. Panoff, and H. Brüssow. 2008. The role of prophage for genome diversification within a clonal lineage of Lactobacillus johnsonii: characterization of the defective prophage LJ771. J. Bacteriol. 1905806-5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desiere, F., C. Mahanivong, A. J. Hillier, P. S. Chandry, B. E. Davidson, and H. Brüssow. 2001. Comparative genomics of lactococcal phages: insight from the complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis phage BK5-T. Virology 283240-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desiere, F., W. M. McShan, D. van Sinderen, J. J. Ferretti, and H. Brüssow. 2001. Comparative genomics reveals close genetic relationships between phages from dairy bacteria and pathogenic streptococci: evolutionary implications for prophage-host interactions. Virology 288325-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dziewit, L., M. Jazurek, L. Drewniak, J. Baj, and D. Bartosik. 2007. The SXT conjugative element and linear prophage N15 encode toxin-antitoxin-stabilizing systems homologous to the tad-ata module of the Paracoccus aminophilus plasmid pAMI2. J. Bacteriol. 1891983-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelberg-Kulka, H., S. Amitai, I. Kolodkin-Gal, and R. Hazan. 2006. Bacterial programmed cell death and multicellular behavior in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelberg-Kulka, H., and G. Glaser. 1999. Addiction modules and programmed cell death and antideath in bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 5343-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelberg-Kulka, H., R. Hazan, and S. Amitai. 2005. mazEF: a chromosomal toxin-antitoxin module that triggers programmed cell death in bacteria. J. Cell Sci. 1184327-4332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enright, A. J., S. Van Dongen, and C. A. Ouzounis. 2002. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 301575-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng, Y., C.-J. Chen, L.-H. Su, S. Hu, J. Yu, and C.-H. Chiu. 2008. Evolution and pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus: lessons learned from genotyping and comparative genomics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 3223-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández-Tornero, C., R. López, E. García, G. Giménez-Gallego, and A. Romero. 2001. A novel solenoid fold in the cell wall anchoring domain of the pneumococcal virulence factor LytA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 81020-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerdes, K. 2000. Toxin-antitoxin modules may regulate synthesis of macromolecules during nutritional stress. J. Bacteriol. 182561-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gindreau, E., R. López, and P. García. 2000. MM1, a temperate bacteriophage of the 23F Spanish/USA multiresistant epidemic clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae: structural analysis of the site-specific integration system. J. Virol. 747803-7813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groth, A. C., and M. P. Calos. 2004. Phage integrases: biology and applications. J. Mol. Biol. 335667-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes, C. S., and R. T. Sauer. 2003. Toxin-antitoxin pairs in bacteria: killers or stress regulators? Cell 1122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiller, N. L., B. Janto, J. S. Hogg, R. Boissy, S. Yu, E. Powell, R. Keefe, N. E. Ehrlich, K. Shen, J. Hayes, K. Barbadora, W. Klimke, D. Dernovoy, T. Tatusova, J. Parkhill, S. D. Bentley, J. C. Post, G. D. Ehrlich, and F. Z. Hu. 2007. Comparative genomic analyses of seventeen Streptococcus pneumoniae strains: insights into the pneumococcal supragenome. J. Bacteriol. 1898186-8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoskisson, P. A., and M. C. M. Smith. 2007. Hypervariation and phase variation in the bacteriophage ‘resistome.’ Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10396-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu, G.-Q., X. Zheng, Y.-F. Yang, P. Ortet, Z.-S. She, and H. Zhu. 2008. ProTISA: a comprehensive resource for translation initiation site annotation in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 36D114-D119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikebe, T., A. Wada, Y. Inagaki, K. Sugama, R. Suzuki, D. Tanaka, A. Tamaru, Y. Fujinaga, Y. Abe, Y. Shimizu, and H. Watanabe. 2002. Dissemination of the phage-associated novel superantigen gene speL in recent invasive and noninvasive Streptococcus pyogenes M3/T3 isolates in Japan. Infect. Immun. 703227-3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingrey, K. T., J. Ren, and J. F. Prescott. 2003. A fluoroquinolone induces a novel mitogen-encoding bacteriophage in Streptococcus canis. Infect. Immun. 713028-3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jardine, P. J., and D. L. Andersen. 2006. DNA packaging in double stranded DNA phages, p. 49-65. In R. Calendar (ed.), The bacteriophages, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- 35.Jeltsch, A., and A. Pingoud. 1996. Horizontal gene transfer contributes to the wide distribution and evolution of type II restriction-modification systems. J. Mol. Evol. 4291-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz, M. E., R. A. Strugnell, and J. I. Rood. 1992. Molecular characterization of a genomic region associated with virulence in Dichelobacter nodosus. Infect. Immun. 604586-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kay, D. 1976. Electron microscopy of small particles, macromolecular structures and nucleic acids. Methods Microbiol. 9177-215. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehnherr, H., E. Maguin, S. Jafri, and M. M. Yarmolinski. 1993. Plasmid addiction genes of bacteriophage P1: doc, which causes cell death on curing of prophage, and phd, which prevents host death when prophage is retained. J. Mol. Biol. 233414-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemos, J. A. C., J. T. A. Brown, J. Abranches, and R. A. Burne. 2005. Characteristics of Streptococcus mutans strains lacking the MazEF and RelBE toxin-antitoxin modules. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine, O. S., K. L. O'Brien, M. Knoll, R. A. Adegbola, S. Black, T. Cherian, R. Dagan, D. Goldblatt, A. Grange, and B. Greenwood. 2006. Pneumococcal vaccination in developing countries. Lancet 3671880-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindsay, J. A., A. Ruzin, H. F. Ross, N. Kurepina, and R. P. Novick. 1998. The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 29527-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llull, D., R. López, and E. García. 2006. Characteristic signatures of the lytA gene provide a rapid and reliable diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441250-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loeffler, J. M., and V. A. Fischetti. 2006. Lysogeny of Streptococcus pneumoniae with MM1 phage: improved adherence and other phenotypic changes. Infect. Immun. 744486-4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.López, R., and E. García. 2004. Recent trends on the molecular biology of pneumococcal capsules, lytic enzymes, and bacteriophage. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28553-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martín, A. C., R. López, and P. García. 1996. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence and functional organization of the genome of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteriophage Cp-1. J. Virol. 703678-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonnell, M., C. Ronda-Laín, and A. Tomasz. 1975. “Diplophage”: a bacteriophage of Diplococcus pneumoniae. Virology 63577-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell, J., I. R. Siboo, D. Takamatsu, H. F. Chambers, and P. M. Sullam. 2007. Mechanism of cell surface expression of the Streptococcus mitis platelet binding proteins PblA and PblB. Mol. Microbiol. 64844-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell, T. J. 2003. The pathogenesis of streptococcal infections: from tooth decay to meningitis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neve, H., K. I. Zenz, F. Desiere, A. Koch, K. J. Heller, and H. Brüssow. 1998. Comparison of the lysogeny modules from the temperate Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages TP-J34 and Sfi21: implications for the modular theory of phage evolution. Virology 24161-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Obregón, V., J. L. García, E. García, R. López, and P. García. 2003. Genome organization and molecular analysis of the temperate bacteriophage MM1 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 1852362-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Obregón, V., P. García, R. López, and J. L. García. 2003. VO1, a temperate bacteriophage of the type 19A multiresistant epidemic 8249 strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae: analysis of variability of lytic and putative C5 methyltransferase genes. Microb. Drug Resist. 97-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pelletier, J., P. Gros, and M. DuBow. June 2000. Development of novel anti-microbial agents based on bacteriophage genomics. U.S. patent WO0032825A2.

- 53.Ramanculov, E., and R. Young. 2001. An ancient player unmasked: T4 rI encodes a t-specific antiholin. Mol. Microbiol. 41575-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramirez, M., E. Severina, and A. Tomasz. 1999. A high incidence of prophage carriage among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 1813618-3625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romero, P., E. García, and T. J. Mitchell. 23 January 2009. Development of a prophage typing system and analysis of prophage carriage in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02155-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Romero, P., R. López, and E. García. 2004. Genomic organization and molecular analysis of the inducible prophage EJ-1, a mosaic myovirus from an atypical pneumococcus. Virology 322239-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M.-A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seguritan, V., I.-W. Feng, F. Rohwer, M. Swift, and A. M. Segall. 2003. Genome sequences of two closely related Vibrio parahaemolyticus phages, VP16T and VP16C. J. Bacteriol. 1856434-6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sevin, E., and F. Barloy-Hubler. 2007. RASTA-Bacteria: a web-based tool for identifying toxin-antitoxin loci in prokaryotes. Genome Biol. 8R155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheehan, M. M., E. Stanley, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen. 1999. Identification and characterization of a lysis module present in a large proportion of bacteriophages infecting Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65569-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siboo, I. R., B. A. Bensing, and P. M. Sullam. 2003. Genomic organization and molecular characterization of SM1, a temperate bacteriophage of Streptococcus mitis. J. Bacteriol. 1856968-6975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sonnhammer, E. L. L., and R. Durbin. 1995. A dot-matrix program with dynamic threshold control suited for genomic DNA and protein sequence analysis. Gene 167GC1-GC10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spratt, B. G. 1999. Multilocus sequence typing: molecular typing of bacterial pathogens in an era of rapid DNA sequencing and the Internet. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2312-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelber, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tiraby, J. G., E. Tiraby, and M. S. Fox. 1975. Pneumococcal bacteriophages. Virology 68566-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Sinderen, D., H. Karsens, J. Kok, P. Terpstra, M. H. Ruiters, G. Venema, and A. Nauta. 1996. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage r1t. Mol. Microbiol. 191343-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waldor, M. K., and D. I. Friedman. 2005. Phage regulatory circuits and virulence gene expression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8459-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang, I.-N., D. L. Smith, and R. Young. 2000. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54799-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zielenkiewicz, U., and P. Cegłowski. 2001. Mechanisms of plasmid stable maintenance with special focus on plasmid addiction system. Acta Biochim. Pol. 481003-1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.