Abstract

In protease-negative human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) [Pr(-)], the amount of  annealed by Gag is modestly reduced (∼25%) compared to that annealed by mature nucleocapsid (NCp7) in protease-positive HIV-1 [Pr(+)]. However, the

annealed by Gag is modestly reduced (∼25%) compared to that annealed by mature nucleocapsid (NCp7) in protease-positive HIV-1 [Pr(+)]. However, the  annealed by Gag also has a strongly reduced ability to initiate reverse transcription and binds less tightly to viral RNA. Both in vivo and in vitro, APOBEC3G (A3G) inhibits

annealed by Gag also has a strongly reduced ability to initiate reverse transcription and binds less tightly to viral RNA. Both in vivo and in vitro, APOBEC3G (A3G) inhibits  annealing facilitated by NCp7 but not annealing facilitated by Gag. While transient exposure of Pr(-) viral RNA to NCp7 in vitro returns the quality and quantity of

annealing facilitated by NCp7 but not annealing facilitated by Gag. While transient exposure of Pr(-) viral RNA to NCp7 in vitro returns the quality and quantity of  annealing to Pr(+) levels, the presence of A3G both prevents this rescue and creates a further reduction in

annealing to Pr(+) levels, the presence of A3G both prevents this rescue and creates a further reduction in  annealing. Since A3G inhibition of NCp7-facilitated

annealing. Since A3G inhibition of NCp7-facilitated  annealing in vitro requires the presence of A3G during the annealing process, these results suggest that in Pr(+) viruses NCp7 can displace Gag-annealed

annealing in vitro requires the presence of A3G during the annealing process, these results suggest that in Pr(+) viruses NCp7 can displace Gag-annealed  and re-anneal it to viral RNA, the re-annealing step being subject to A3G inhibition. This supports the possibility that the initial annealing of

and re-anneal it to viral RNA, the re-annealing step being subject to A3G inhibition. This supports the possibility that the initial annealing of  in wild-type, Pr(+) virus may be by Gag and not by NCp7, perhaps offering the advantage of Gag's preference for binding to RNA stem-loops in the 5′ region of viral RNA near the

in wild-type, Pr(+) virus may be by Gag and not by NCp7, perhaps offering the advantage of Gag's preference for binding to RNA stem-loops in the 5′ region of viral RNA near the  annealing region.

annealing region.

In human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), minus-strand viral DNA synthesis by reverse transcriptase (RT) is initiated by a cellular tRNA,  , which binds to sequences in the 5′ region of the viral RNA genome (33). These sequences include the primer binding site (PBS), an 18-nucleotide (nt) sequence complementary to the 3′-terminal 18 nt of

, which binds to sequences in the 5′ region of the viral RNA genome (33). These sequences include the primer binding site (PBS), an 18-nucleotide (nt) sequence complementary to the 3′-terminal 18 nt of  , and an 8-nt sequence upstream of the PBS, known as the primer activation signal, that is complementary to the 5′ portion of the TΨC arm in

, and an 8-nt sequence upstream of the PBS, known as the primer activation signal, that is complementary to the 5′ portion of the TΨC arm in  (3, 4).

(3, 4).

It has been shown that primer tRNA annealing occurs independently of precursor processing in HIV-1 (30), murine retrovirus (14), and avian retrovirus (45). Annealing of  to viral RNA is facilitated by nucleocapsid protein. Both the mature nucleocapsid (NCp7) and nucleocapsid sequences within the precursor Gag protein facilitate annealing (11). HIV-1 nucleocapsid has two zinc fingers. The basic amino acids flanking the N-terminal zinc finger are required for

to viral RNA is facilitated by nucleocapsid protein. Both the mature nucleocapsid (NCp7) and nucleocapsid sequences within the precursor Gag protein facilitate annealing (11). HIV-1 nucleocapsid has two zinc fingers. The basic amino acids flanking the N-terminal zinc finger are required for  annealing, but the two zinc fingers appear to have less effect (10, 15, 24, 34). The role of nucleocapsid in the annealing process has been predicted to be twofold (23). One role is to facilitate a nucleation step that brings

annealing, but the two zinc fingers appear to have less effect (10, 15, 24, 34). The role of nucleocapsid in the annealing process has been predicted to be twofold (23). One role is to facilitate a nucleation step that brings  and the largely, if not entirely (depending on the RNA model used), single-stranded PBS sequences together, which is probably facilitated primarily by the basic amino acids flanking the first zinc finger. Other roles, which may be facilitated by the zinc fingers, may be to both denature double-stranded RNA regions in viral RNA involved in annealing (such as the primer activation signal), and/or alter RNA conformation to make such regions more available for annealing. Smaller effects on the rate of annealing by mutated zinc fingers may be explained by the fact that, while the mutant NCp7 is a weaker duplex destabilizer, it is a better duplex nucleating agent, and the two phenomenon may balance each other (23). NCp7 has also been predicted to play a role in blocking the interaction between the TΨC and D loops of

and the largely, if not entirely (depending on the RNA model used), single-stranded PBS sequences together, which is probably facilitated primarily by the basic amino acids flanking the first zinc finger. Other roles, which may be facilitated by the zinc fingers, may be to both denature double-stranded RNA regions in viral RNA involved in annealing (such as the primer activation signal), and/or alter RNA conformation to make such regions more available for annealing. Smaller effects on the rate of annealing by mutated zinc fingers may be explained by the fact that, while the mutant NCp7 is a weaker duplex destabilizer, it is a better duplex nucleating agent, and the two phenomenon may balance each other (23). NCp7 has also been predicted to play a role in blocking the interaction between the TΨC and D loops of  , thereby facilitating a destabilization of tertiary structure which might also promote annealing (24, 46).

, thereby facilitating a destabilization of tertiary structure which might also promote annealing (24, 46).

Earlier studies have indicated that in protease-negative (Pr(−)) HIV-1, Gag is sufficient for annealing  to the viral RNA (10, 16). However, the placement of

to the viral RNA (10, 16). However, the placement of  on viral RNA is not optimal, since the incorporation of the first deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), dCTP, was reduced by >70% in an in vitro reverse transcription system consisting of total viral RNA as the source of the primer

on viral RNA is not optimal, since the incorporation of the first deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), dCTP, was reduced by >70% in an in vitro reverse transcription system consisting of total viral RNA as the source of the primer  /viral RNA template, exogenous HIV-1 RT, and a suboptimal concentration of dCTP that did not allow for complete incorporation of dCTP (11). In the present study, we provide further evidence for a weaker binding of

/viral RNA template, exogenous HIV-1 RT, and a suboptimal concentration of dCTP that did not allow for complete incorporation of dCTP (11). In the present study, we provide further evidence for a weaker binding of  annealed to viral RNA by Gag rather than by NCp7, by showing that

annealed to viral RNA by Gag rather than by NCp7, by showing that  annealed by Gag is more readily displaced from the PBS by reverse transcription initiated from a DNA primer downstream of the PBS.

annealed by Gag is more readily displaced from the PBS by reverse transcription initiated from a DNA primer downstream of the PBS.

We have also used here the ability of the antiviral protein APOBEC3G (A3G) to inhibit  annealing in HIV-1 (20, 21) to deduce the roles of Gag and NCp7 in the annealing process in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. HIV-1 produced from cells expressing human APOBEC3G (A3G), also known as nonpermissive cells, has a severely reduced ability to productively infect other cells. A3G is incorporated into Vif-negative HIV-1 that are either protease-positive [Pr(+)] or Pr(−) (9), and its incorporation depends upon the interaction of A3G with nucleocapsid sequences in Gag (1, 9, 38, 44, 49). The presence of the HIV-1 protein Vif greatly inhibits this incorporation due to a cytoplasmic interaction with A3G that results in A3G's degradation via proteasomes (48).

annealing in HIV-1 (20, 21) to deduce the roles of Gag and NCp7 in the annealing process in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. HIV-1 produced from cells expressing human APOBEC3G (A3G), also known as nonpermissive cells, has a severely reduced ability to productively infect other cells. A3G is incorporated into Vif-negative HIV-1 that are either protease-positive [Pr(+)] or Pr(−) (9), and its incorporation depends upon the interaction of A3G with nucleocapsid sequences in Gag (1, 9, 38, 44, 49). The presence of the HIV-1 protein Vif greatly inhibits this incorporation due to a cytoplasmic interaction with A3G that results in A3G's degradation via proteasomes (48).

New infections by HIV-1 containing A3G are accompanied by a reduced production of viral DNA transcripts (19, 36, 39, 41). Although it has been suggested that cytidine deamination by A3G of newly synthesized DNA results in this DNA's degradation (25, 35, 40, 52), other reports have indicated that the reduced viral DNA production is due to a direct inhibition of reverse transcription, occurring at both the initiation stage of reverse transcription (20, 21) and at the first and/or second DNA strand transfer stages (37, 42). We have provided evidence that the reduction in the initiation of reverse transcription is associated with an inhibition of  annealing to the viral RNA genome by A3G (20, 21). This inhibition of annealing by A3G has been reported in naturally nonpermissive cells, such as H9 and MT2 (20), and in permissive cells that express exogenous A3G (293T cells) (20). A3G has also been reported to inhibit the NCp7-facilitated annealing of

annealing to the viral RNA genome by A3G (20, 21). This inhibition of annealing by A3G has been reported in naturally nonpermissive cells, such as H9 and MT2 (20), and in permissive cells that express exogenous A3G (293T cells) (20). A3G has also been reported to inhibit the NCp7-facilitated annealing of  in vitro (21). In the latter report, we showed that (i) the in vitro inhibition of

in vitro (21). In the latter report, we showed that (i) the in vitro inhibition of  annealing by A3G is dependent upon an interaction occurring between NCp7 and A3G and (ii) that A3G, once annealed by NCp7, cannot alter annealing, i.e., A3G must be present during the annealing process in order to inhibit it. In the present study, we also show, using Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, that the ability of A3G to inhibit annealing and initiation of reverse transcription only applies to

annealing by A3G is dependent upon an interaction occurring between NCp7 and A3G and (ii) that A3G, once annealed by NCp7, cannot alter annealing, i.e., A3G must be present during the annealing process in order to inhibit it. In the present study, we also show, using Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, that the ability of A3G to inhibit annealing and initiation of reverse transcription only applies to  annealed by NCp7 and not to

annealed by NCp7 and not to  annealed by Gag, and we use this property of A3G to examine the temporal roles of Gag and NCp7 in promoting

annealed by Gag, and we use this property of A3G to examine the temporal roles of Gag and NCp7 in promoting  annealing in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions.

annealing in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

BH10 is a simian virus 40-based vector that contains full-length wild-type BH10 strain of HIV-1 proviral DNA, while BH10P− contains an inactive viral protease (D25G). The constructions of BH10.Vif− [(Pr(+)Vif(−)] and BH10P−Vif− [Pr(−)Vif(−)] were done by introducing into BH10 and BH10P− a stop codon right after the start codon (ATG) of the Vif reading frame at nt 5043by using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the primer pair 5′-AGATCATTAGGGATTTAGGAAAACAGATGGCAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCCATCTGTTTTCCTAAATCCCTAATGATCT-3′. The human pAPOBEC3G was constructed as previously described (9) and expresses wild-type human APOBEC3G with a fused hemagglutinin (HA) tag at the C terminus.

Protein production.

Human A3G was obtained from Diagnostics, Inc. It was produced in baculovirus and was purified by (NH4)2SO4 fractionation and immunoaffinity chromatography to >95% purity. HIV-1 RT, purified from bacteria as previously described (29), was a gift from Matthias Gotte (McGill University). Recombinant wild-type NCp7 was a gift from R. Gorelick and was prepared as previously described (8, 22), including purification by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography after the protein was denatured in 8 M guanidine hydrochloride.

GagΔp6 was a gift from A. Rein and was prepared as previously described (11). GagΔp6 was used because it is easier to purify than full-length Gag, its assembly properties in vitro have been characterized (7), and it can efficiently facilitate the annealing of  to viral RNA (16).

to viral RNA (16).

Cells, transfections, and virus purification.

HEK-293T cells were grown in complete Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. For the production of viruses, HEK-293T cells were transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Supernatant was collected at 48 h posttransfection. Viruses were pelleted from culture medium by centrifugation in a Beckman Ti-45 rotor at 35,000 rpm for 1 h. The viral pellets were then purified by 15% sucrose onto a 65% sucrose cushion. The band of purified virus was removed and pelleted in 1× TNE (20 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) in a Beckman Ti-45 rotor at 40,000 rpm for 1 h.

Viral RNA isolation and quantitation.

Total viral RNA was extracted from viral pellets by using the guanidinium isothiocyanate procedure as previously described (28) and was dissolved in 5 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5). As described in an earlier study (11), hybridization to dot blots of total viral RNA were carried out with 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA probes complementary to either the 3′-terminal 18 nt of  (5′-TGGCGCCCGAACAGGGAC-3′) or to the 5′ end of the HIV-1 genomic RNA, just upstream of the PBS (5′-CTGACGCTCTCGCACCC-3′).

(5′-TGGCGCCCGAACAGGGAC-3′) or to the 5′ end of the HIV-1 genomic RNA, just upstream of the PBS (5′-CTGACGCTCTCGCACCC-3′).

-primed initiation of reverse transcription.

-primed initiation of reverse transcription.

Total viral RNA isolated from virus produced in transfected 293T cells was used as the source of a primer tRNA annealed to viral RNA in an in vitro reverse transcription reaction as previously described (29). Briefly, total viral RNA was incubated at 37°C for 15 min in 20 μl of RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 60 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) containing 50 ng of purified HIV RT, 10 U of RNasin, and various dNTPs. To measure the ability of annealed  to be extended by six deoxyribonucleotides, the RT reaction mixture contained 200 μM dCTP, 200 μM dTTP, 5 μCi of [α-32P]dGTP (0.16 μM), and 50 μM ddATP.

to be extended by six deoxyribonucleotides, the RT reaction mixture contained 200 μM dCTP, 200 μM dTTP, 5 μCi of [α-32P]dGTP (0.16 μM), and 50 μM ddATP.

The reaction conditions for the +6-nt extension assay were established previously (11), and the reactions contained all of the reagents, including dNTPs, in excess, so that the amount of dNTP extension is proportional to the amount of  annealed to the viral RNA. In that same study, we also prepared a dose curve using increasing amounts of dCTP, and measured the amount of

annealed to the viral RNA. In that same study, we also prepared a dose curve using increasing amounts of dCTP, and measured the amount of  extended only by the first dNTP, dCTP. We found that at lower concentrations of dCTP the amount of

extended only by the first dNTP, dCTP. We found that at lower concentrations of dCTP the amount of  extended is determined by the dCTP concentration and not by the amount of

extended is determined by the dCTP concentration and not by the amount of  annealed to the viral RNA. At such suboptimal concentrations of dCTP (i.e., 0.16 μM), equal amounts of

annealed to the viral RNA. At such suboptimal concentrations of dCTP (i.e., 0.16 μM), equal amounts of  annealed by Gag or NCp7 (determined by the +6-nt extension) produce very different amounts +1 extensions, which we have interpreted as reflecting different annealing conformations that reflect different efficiencies for the anneale

annealed by Gag or NCp7 (determined by the +6-nt extension) produce very different amounts +1 extensions, which we have interpreted as reflecting different annealing conformations that reflect different efficiencies for the anneale  in capturing this first dNTP. Thus, to measure the ability of annealed

in capturing this first dNTP. Thus, to measure the ability of annealed  to be extended by one deoxyribonucleotide, the RT reaction mixture contained only 0.16 μM [α-32P]dCTP. Reaction products were resolved by using one-dimensional (1D) 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) containing 7 M urea (29).

to be extended by one deoxyribonucleotide, the RT reaction mixture contained only 0.16 μM [α-32P]dCTP. Reaction products were resolved by using one-dimensional (1D) 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) containing 7 M urea (29).

Transient exposure of viral RNA from BH10 or BH10P− to A3G in the presence of either bovine serum albumin (BSA), NCp7, or GagΔp6.

Total viral RNA from BH10 or BH10P− was transiently exposed for 30 min at 37°C to A3G in the presence of 10 pmol of either BSA, NCp7, or GagΔp6. Deproteinization was performed through the addition of 1 ml of proteinase K (5 mg/ml) to the reactions, which were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction to remove both proteinase K and digested residual proteins. The viral RNA complex was ethanol precipitated, dried, and used in the +6 RT reaction.

occupation of the PBS.

occupation of the PBS.

A 28-nt DNA oligomer (5′-CCCCGCTTAATACTG ACGCTCTCGCACC-3′) was 5′ end labeled with 32P using T4 kinase and was complementary to sequences in HIV-1 RNA genome 139 bases downstream of the PBS. The complex was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min in 20 μl of RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 60 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT) containing 50 ng of HIV RT, 10 U of RNasin, 200 μM concentrations of dNTPs, and reaction products, including full-length (365 nt) and truncated (167 nt, due to occupation of the PBS by  ) products, were resolved by using 1D 6% PAGE with gels containing 7 M urea.

) products, were resolved by using 1D 6% PAGE with gels containing 7 M urea.

In vitro annealing of  to viral RNA.

to viral RNA.

Human placental  was hybridized with synthetic HIV-1 viral genomic RNA. The

was hybridized with synthetic HIV-1 viral genomic RNA. The  was purified from human placenta as previously described (32), using standard chromatography procedures (sequentially DEAE-Sephadex A-50, reversed-phase chromatography [RPC-5], and Porex C4) and, finally, 2D PAGE. The synthetic genomic RNA (497 bases), comprising the complete R and U5 regions, the PBS, leader, and part of the gag coding region, was synthesized as previously described (29) from the AccI-linearized plasmid pHIV-PBS (2) with the MEGAscript transcription system (Ambion, Inc.).

was purified from human placenta as previously described (32), using standard chromatography procedures (sequentially DEAE-Sephadex A-50, reversed-phase chromatography [RPC-5], and Porex C4) and, finally, 2D PAGE. The synthetic genomic RNA (497 bases), comprising the complete R and U5 regions, the PBS, leader, and part of the gag coding region, was synthesized as previously described (29) from the AccI-linearized plasmid pHIV-PBS (2) with the MEGAscript transcription system (Ambion, Inc.).

For heat annealing of  , 1 pmol of

, 1 pmol of  was combined with 1 pmol of synthetic HIV-1 RNA template in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, and 10 U of RNasin. The annealing reaction mixture was heated sequentially at 85°C for 5 min, at 50°C for 10 min, and then at 37°C for 15 min.

was combined with 1 pmol of synthetic HIV-1 RNA template in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, and 10 U of RNasin. The annealing reaction mixture was heated sequentially at 85°C for 5 min, at 50°C for 10 min, and then at 37°C for 15 min.

annealing to viral RNA was facilitated by the addition of either NCp7 or GagΔp6 as previously described (11). In order to have

annealing to viral RNA was facilitated by the addition of either NCp7 or GagΔp6 as previously described (11). In order to have  annealing sensitive to regulation by NCp7, GagΔp6, or A3G, in vitro conditions were used that did not maximize annealing. We have previously shown that initiation of reverse transcription (+6-nt extension) increases linearly when 1 pmol of

annealing sensitive to regulation by NCp7, GagΔp6, or A3G, in vitro conditions were used that did not maximize annealing. We have previously shown that initiation of reverse transcription (+6-nt extension) increases linearly when 1 pmol of  is annealed to 1 pmol of synthetic HIV-1 RNA using from 30 to 60 pmol of NCp7 (21). We therefore used 30 pmol in the in vitro annealing system, which was also determined in that study (21) to result in 47% occupancy of the PBS. In that earlier study, we also noted that the maximum inhibition of the initiation of reverse transcription occurs at an A3G:NCp7 ratio of 1:30, so we used 1 pmol of A3G in the annealing reaction for our inhibition studies.

is annealed to 1 pmol of synthetic HIV-1 RNA using from 30 to 60 pmol of NCp7 (21). We therefore used 30 pmol in the in vitro annealing system, which was also determined in that study (21) to result in 47% occupancy of the PBS. In that earlier study, we also noted that the maximum inhibition of the initiation of reverse transcription occurs at an A3G:NCp7 ratio of 1:30, so we used 1 pmol of A3G in the annealing reaction for our inhibition studies.

Thus, 1 pmol of  was annealed to 1 pmol of synthetic HIV-1 RNA template by incubating these reagents at 37°C for 90 min with 30 pmol of NCp7 or GagΔp6 in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT) and 10 U of RNasin. To study the effect of A3G on these annealing reactions, 1 pmol of either purified A3G or control BSA, dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.01% sarcosyl, was added to the annealing reactions at the start. After the annealing and in preparation for the

was annealed to 1 pmol of synthetic HIV-1 RNA template by incubating these reagents at 37°C for 90 min with 30 pmol of NCp7 or GagΔp6 in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT) and 10 U of RNasin. To study the effect of A3G on these annealing reactions, 1 pmol of either purified A3G or control BSA, dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.01% sarcosyl, was added to the annealing reactions at the start. After the annealing and in preparation for the  priming reaction (+1- or +6-nt extension), the

priming reaction (+1- or +6-nt extension), the  /viral RNA complex was deproteinized by the addition of 1 μl of proteinase K (5 mg/ml) and was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction to remove both proteinase K and digested residual proteins and ethanol precipitation of the viral RNA complex.

/viral RNA complex was deproteinized by the addition of 1 μl of proteinase K (5 mg/ml) and was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction to remove both proteinase K and digested residual proteins and ethanol precipitation of the viral RNA complex.

To directly measure the amount of  annealed, we used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

annealed, we used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay.  was 3′ end labeled with 32pCp, as previously described (6). After deproteinization of the annealed complex with proteinase K, the free

was 3′ end labeled with 32pCp, as previously described (6). After deproteinization of the annealed complex with proteinase K, the free  was resolved from primer complexed with viral RNA using 1D 6% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

was resolved from primer complexed with viral RNA using 1D 6% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

RESULTS

A3G inhibits the initiation of reverse transcription in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions but not in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions.

In the present study, Vif-negative HIV-1 were used to allow for the incorporation of A3G into the viruses. 293T cells were cotransfected with a plasmid coding for either Pr(+)Vif(−) or Pr(−)Vif(−) HIV-1, and a plasmid coding for, or not coding for, A3G. We have previously reported that we needed to produce >10-fold more A3G in 293T cells to achieve the same amount of inhibition of  annealing as achieved in nonpermissive cells such as H9 or MT2 cells (20). We interpreted this to mean that A3G expression in 293T cells is not enough to make the cell nonpermissive, and there are probably other unknown factors involved to achieve the same inhibition of annealing found in H9 or MT2 cells at lower A3G concentrations. Also, in spite of a recent report that the presence of Vif can influence the in vitro annealing of

annealing as achieved in nonpermissive cells such as H9 or MT2 cells (20). We interpreted this to mean that A3G expression in 293T cells is not enough to make the cell nonpermissive, and there are probably other unknown factors involved to achieve the same inhibition of annealing found in H9 or MT2 cells at lower A3G concentrations. Also, in spite of a recent report that the presence of Vif can influence the in vitro annealing of  (26), this is at odds with what we have previously reported, i.e., that the absence of Vif has no effect upon

(26), this is at odds with what we have previously reported, i.e., that the absence of Vif has no effect upon  incorporation or initiation of reverse transcription in virions produced from permissive 293T cells (20). Total viral RNA was isolated from each of the four types of viruses, and the content of viral genomic RNA and

incorporation or initiation of reverse transcription in virions produced from permissive 293T cells (20). Total viral RNA was isolated from each of the four types of viruses, and the content of viral genomic RNA and  in the total viral RNA was determined by hybridizing dot blots of the RNA with 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA probes complementary to either the 3′-terminal 18 nt of

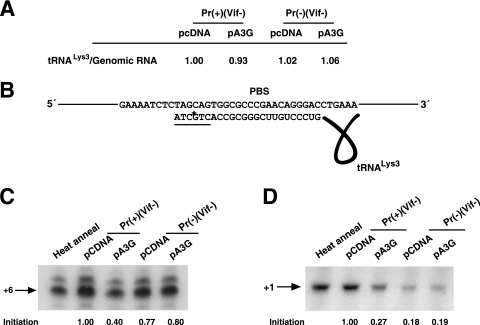

in the total viral RNA was determined by hybridizing dot blots of the RNA with 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA probes complementary to either the 3′-terminal 18 nt of  or the 5′ end of the HIV-1 genomic RNA, upstream of the PBS. Figure 1A shows that all four types of virions have equal

or the 5′ end of the HIV-1 genomic RNA, upstream of the PBS. Figure 1A shows that all four types of virions have equal  /viral RNA ratios, suggesting that

/viral RNA ratios, suggesting that  incorporation is not affected either by the inability to process viral proteins or by the presence of A3G in the cell and virus.

incorporation is not affected either by the inability to process viral proteins or by the presence of A3G in the cell and virus.

FIG. 1.

incorporation and initiation of reverse transcription in Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) HIV-1, lacking or containing A3G. Four types of virions were produced from 293T cells cotransfected with a plasmid coding for Pr(+)Vif(−) or Pr(−)Vif(−) and a plasmid coding or not coding for A3G. Total viral RNA was isolated. (A)

incorporation and initiation of reverse transcription in Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) HIV-1, lacking or containing A3G. Four types of virions were produced from 293T cells cotransfected with a plasmid coding for Pr(+)Vif(−) or Pr(−)Vif(−) and a plasmid coding or not coding for A3G. Total viral RNA was isolated. (A)  /viral genomic RNA ratios in virions, as determined by dot blot hybridization of total viral RNA with a probe specific for either viral RNA or

/viral genomic RNA ratios in virions, as determined by dot blot hybridization of total viral RNA with a probe specific for either viral RNA or  . The values were normalized to that obtained for Pr(+)Vif(−) produced in the absence of A3G. (B to D) Relative initiation of reverse transcription. (B) Diagram of the

. The values were normalized to that obtained for Pr(+)Vif(−) produced in the absence of A3G. (B to D) Relative initiation of reverse transcription. (B) Diagram of the  /genomic RNA complex, with the 6-nt extension produced by RT underlined. (C) Six-nucleotide extension of

/genomic RNA complex, with the 6-nt extension produced by RT underlined. (C) Six-nucleotide extension of  . Total viral RNA was used as the source of primer or template in an in vitro reverse transcription system, as described in the text. In the reaction mix, dGTP is labeled, and dATP is replaced with ddATP. Shown are the resolution by 1D PAGE of the 6-nt extension products of

. Total viral RNA was used as the source of primer or template in an in vitro reverse transcription system, as described in the text. In the reaction mix, dGTP is labeled, and dATP is replaced with ddATP. Shown are the resolution by 1D PAGE of the 6-nt extension products of  and the quantitation, listed under each lane, of the amount of 6-nt extension per equal amount of genomic RNA, relative to that obtained for Pr(+)Vif(−). (D) One-nucleotide (dCTP) extension of

and the quantitation, listed under each lane, of the amount of 6-nt extension per equal amount of genomic RNA, relative to that obtained for Pr(+)Vif(−). (D) One-nucleotide (dCTP) extension of  . Total viral RNA was used as the source of primer or template in an in vitro reverse transcription system, as described in the text, whose only dNTP is labeled dCTP, present at suboptimal concentrations (0.16 μM), as previously determined (11). Shown are the resolution by 1D PAGE of the 1-nt extension products of

. Total viral RNA was used as the source of primer or template in an in vitro reverse transcription system, as described in the text, whose only dNTP is labeled dCTP, present at suboptimal concentrations (0.16 μM), as previously determined (11). Shown are the resolution by 1D PAGE of the 1-nt extension products of  , and the quantitation, listed under each lane, of the amount of 1-nt extension per equal amount of genomic RNA, relative to that obtained for Pr(+)Vif(−). Experiments were performed twice.

, and the quantitation, listed under each lane, of the amount of 1-nt extension per equal amount of genomic RNA, relative to that obtained for Pr(+)Vif(−). Experiments were performed twice.

Initiation of reverse transcription was measured in an in vitro reverse transcription assay that extends the  by 6 nt, using total viral RNA as the source of primer

by 6 nt, using total viral RNA as the source of primer  annealed to viral RNA (see the diagram in Fig. 1B). Reaction products were resolved by using 6% 1D PAGE containing 7 M urea. Figure 1C shows the 1D PAGE pattern of the 6-nt-extended

annealed to viral RNA (see the diagram in Fig. 1B). Reaction products were resolved by using 6% 1D PAGE containing 7 M urea. Figure 1C shows the 1D PAGE pattern of the 6-nt-extended  produced from the RNA isolated from each viral type, with the relative initiation normalized to Pr(−)Vif(−) listed below each lane. As previously reported (11), 6-nt extension of

produced from the RNA isolated from each viral type, with the relative initiation normalized to Pr(−)Vif(−) listed below each lane. As previously reported (11), 6-nt extension of  in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses is reduced ca. 23% from that found for Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. Also, in PR(+)Vif(−) virions the presence of A3G reduces the relative initiation of reverse transcription to 40% of that obtained in the absence of A3G. However, A3G has no further effect on initiation in PR(−)Vif(−) viruses.

in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses is reduced ca. 23% from that found for Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. Also, in PR(+)Vif(−) virions the presence of A3G reduces the relative initiation of reverse transcription to 40% of that obtained in the absence of A3G. However, A3G has no further effect on initiation in PR(−)Vif(−) viruses.

As we have previously reported (11), the +6-nt extension assay contains an excess of dNTPs, which hides more subtle differences in the ability of  to initiate reverse transcription when annealing of the

to initiate reverse transcription when annealing of the  has occurred in either a Pr(−)Vif(−) or a Pr(+)Vif(−) environment. Such differences can be detected when the first dNTP incorporated, dCTP, is present at suboptimal quantities in the reverse transcription assay. This is shown in Fig. 1D, in which the initiation of reverse transcription is measured by using total viral RNA as the source of primer or template, and which occurs in the presence of only one dNTP, 0.16 μM [α-32P]dCTP. The ability of Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses to incorporate dCTP is reduced to less than 20% of that found for viral RNA from Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses, independently of the presence of A3G. We also show that the presence of A3G in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses reduces the +1 extension to 27% of that found for Pr(+)Vif(−) virions not containing A3G, an even larger reduction than we report for the 6-nt extension assay (Fig. 1C). As also seen for +6-nt extension (Fig. 1C), A3G shows no effect upon +1-nt extension in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions.

has occurred in either a Pr(−)Vif(−) or a Pr(+)Vif(−) environment. Such differences can be detected when the first dNTP incorporated, dCTP, is present at suboptimal quantities in the reverse transcription assay. This is shown in Fig. 1D, in which the initiation of reverse transcription is measured by using total viral RNA as the source of primer or template, and which occurs in the presence of only one dNTP, 0.16 μM [α-32P]dCTP. The ability of Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses to incorporate dCTP is reduced to less than 20% of that found for viral RNA from Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses, independently of the presence of A3G. We also show that the presence of A3G in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses reduces the +1 extension to 27% of that found for Pr(+)Vif(−) virions not containing A3G, an even larger reduction than we report for the 6-nt extension assay (Fig. 1C). As also seen for +6-nt extension (Fig. 1C), A3G shows no effect upon +1-nt extension in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions.

The effect of lack of viral protein processing and/or A3G upon the occupancy of the primer binding site by  .

.

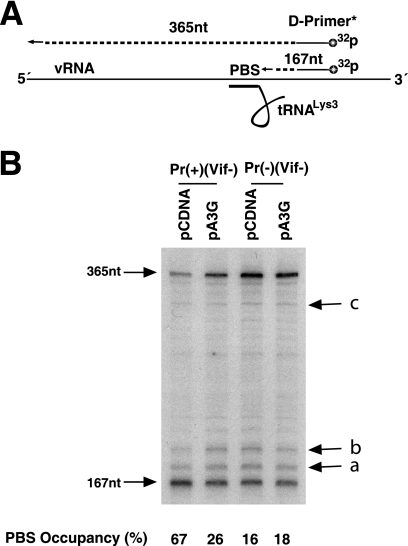

Differences in the ability of RNA from these different viruses to extend  by 6 nt may reflect similar differences in the amount of

by 6 nt may reflect similar differences in the amount of  annealed in vivo. To further investigate this, we have used another assay that more directly measures

annealed in vivo. To further investigate this, we have used another assay that more directly measures  annealing by determining the fraction of PBSs occupied by

annealing by determining the fraction of PBSs occupied by  . A diagram of the experimental strategy is shown in Fig. 2A. A 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA primer (28 nt) is annealed to a sequence in total viral RNA 139 nt downstream of the PBS and is then extended with HIV-1 RT. Full-length extension will give a labeled 365-nt product but

. A diagram of the experimental strategy is shown in Fig. 2A. A 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA primer (28 nt) is annealed to a sequence in total viral RNA 139 nt downstream of the PBS and is then extended with HIV-1 RT. Full-length extension will give a labeled 365-nt product but  annealed at the PBS will block extension, resulting in a 167-nt product. Resolution of these products by 1D PAGE is shown in Fig. 2B. In addition to the 167-nt blocked product and the 365-nt full-length extension product, run-through products not reaching full length are also seen, and the major ones—a, b, and c (marked with arrows in the figure)—have been included in the calculation, i.e., the percentage of the PBSs that are occupied is equal to the 167-nt product/the 167-nt + the 365-nt + the a+b+c nucleotide products. This value is listed below each lane. The first two lanes show that the PBS occupancy by

annealed at the PBS will block extension, resulting in a 167-nt product. Resolution of these products by 1D PAGE is shown in Fig. 2B. In addition to the 167-nt blocked product and the 365-nt full-length extension product, run-through products not reaching full length are also seen, and the major ones—a, b, and c (marked with arrows in the figure)—have been included in the calculation, i.e., the percentage of the PBSs that are occupied is equal to the 167-nt product/the 167-nt + the 365-nt + the a+b+c nucleotide products. This value is listed below each lane. The first two lanes show that the PBS occupancy by  in Pr(+)Vif(−) is reduced from 67% occupancy to 26% occupancy when A3G is present, i.e., A3G reduces annealing by 62%. This number is very similar to the 60% reduction in initiation measured using the

in Pr(+)Vif(−) is reduced from 67% occupancy to 26% occupancy when A3G is present, i.e., A3G reduces annealing by 62%. This number is very similar to the 60% reduction in initiation measured using the  6-nt extension assay (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that changes in

6-nt extension assay (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that changes in  initiation of reverse transcription under conditions of excess dNTPs reflect changes in the amount of

initiation of reverse transcription under conditions of excess dNTPs reflect changes in the amount of  annealed to the PBS.

annealed to the PBS.

FIG. 2.

Measurements of the occupancy of the PBS by  in Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) HIV-1, lacking or containing A3G. Total viral RNA samples isolated from the four virus types listed in Fig. 1 were used to determine PBS occupancy by

in Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) HIV-1, lacking or containing A3G. Total viral RNA samples isolated from the four virus types listed in Fig. 1 were used to determine PBS occupancy by  . (A) Diagram showing the strategy used to measure the percentage of the PBSs occupied with

. (A) Diagram showing the strategy used to measure the percentage of the PBSs occupied with  . A 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA primer (28 nt) was annealed 139 bases downstream of the PBS in viral RNA and extended with reverse transcription. The full-length extension product is 365 nt, while a truncated product, resulting from blocked extension by the presence of

. A 5′-32P-end-labeled DNA primer (28 nt) was annealed 139 bases downstream of the PBS in viral RNA and extended with reverse transcription. The full-length extension product is 365 nt, while a truncated product, resulting from blocked extension by the presence of  on the PBS, is 167 nt. (B) Separation of the full-length and truncated extension products by 1D PAGE. The ratio of truncated product to truncated, full-length product and fragments (a+b+c) × 100 is equal to the percentage of PBSs occupied by

on the PBS, is 167 nt. (B) Separation of the full-length and truncated extension products by 1D PAGE. The ratio of truncated product to truncated, full-length product and fragments (a+b+c) × 100 is equal to the percentage of PBSs occupied by  , and these values are indicated at the bottom of each lane. Occupancy assays were repeated three times.

, and these values are indicated at the bottom of each lane. Occupancy assays were repeated three times.

The value of 67% occupancy of the PBS achieved in the absence of A3G may be considered a minimum value since we do not know if the block to elongation by  annealed to the PBS is 100% efficient. On the other hand, since we have previously shown in an in vitro

annealed to the PBS is 100% efficient. On the other hand, since we have previously shown in an in vitro  annealing system that PBS occupancy is only 1% when

annealing system that PBS occupancy is only 1% when  is absent in a system containing both synthetic viral RNA and NCp7 (21), it is not likely that an unoccupied PBS is in a configuration that can partially block RT elongation. PBS run-through bands a, b, and c are also seen in the in vitro system with no

is absent in a system containing both synthetic viral RNA and NCp7 (21), it is not likely that an unoccupied PBS is in a configuration that can partially block RT elongation. PBS run-through bands a, b, and c are also seen in the in vitro system with no  present (21), suggesting that these bands are due to natural pause sites of DNA synthesis that occur independently of PBS occupancy.

present (21), suggesting that these bands are due to natural pause sites of DNA synthesis that occur independently of PBS occupancy.

The +6-nt extension data seen in Fig. 1C suggest that the amount of  annealed to viral RNA isolated from Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses is 77% that of the value found in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions, and that the much lower +1-nt extension (18% that of the value found in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions (Fig. 1D) may therefore be due to a nonoptimal placement of the annealed

annealed to viral RNA isolated from Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses is 77% that of the value found in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions, and that the much lower +1-nt extension (18% that of the value found in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions (Fig. 1D) may therefore be due to a nonoptimal placement of the annealed  on the viral RNA that lessens its ability to incorporate the first nucleotide. This proposed weaker binding of

on the viral RNA that lessens its ability to incorporate the first nucleotide. This proposed weaker binding of  to viral RNA in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses is also supported by measurements of PBS occupancy in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses. For while the amount of annealed

to viral RNA in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses is also supported by measurements of PBS occupancy in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses. For while the amount of annealed  may only be reduced 23% in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, the amount annealed as measured by the PBS occupancy assay is reduced 75%, suggesting that the

may only be reduced 23% in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, the amount annealed as measured by the PBS occupancy assay is reduced 75%, suggesting that the  annealed in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions is more readily displaced by the extension from the downstream DNA primer than is annealed

annealed in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions is more readily displaced by the extension from the downstream DNA primer than is annealed  in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions. This reduction in occupancy is not influenced by the presence or absence of A3G.

in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions. This reduction in occupancy is not influenced by the presence or absence of A3G.

Effect of A3G upon the in vitro annealing of  to viral RNA that is facilitated by either GagΔp6 or NCp7.

to viral RNA that is facilitated by either GagΔp6 or NCp7.

Although we have previously shown that A3G does not affect the viral production of Pr(+)Vif(−) or its RNA content (20), it is technically difficult to determine whether either the production of virions or the RNA content/virus has been altered between Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−), because of the different sensitivity of capsid and Gag to anti-p24. We have therefore studied the effect of A3G upon  annealed by either NCp7 or Gag in vitro, where viral production and genomic RNA is not an issue. The results obtained above using viral RNA isolated from Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions also assume that the key difference in

annealed by either NCp7 or Gag in vitro, where viral production and genomic RNA is not an issue. The results obtained above using viral RNA isolated from Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions also assume that the key difference in  annealing and its susceptibility to inhibition by A3G in the two viral types depends upon whether Gag or NCp7 is used for annealing. To test this assumption, we performed similar studies in vitro, where

annealing and its susceptibility to inhibition by A3G in the two viral types depends upon whether Gag or NCp7 is used for annealing. To test this assumption, we performed similar studies in vitro, where  is annealed to synthetic viral RNA using either GagΔp6 or NCp7, in the presence or absence of A3G. As described in detail in Materials and Methods, the in vitro conditions for annealing produced intermediate amounts of

is annealed to synthetic viral RNA using either GagΔp6 or NCp7, in the presence or absence of A3G. As described in detail in Materials and Methods, the in vitro conditions for annealing produced intermediate amounts of  annealing, in order to ensure sensitivity to differences in annealing obtained when annealing with GagΔp6 or NCp7 in the presence or absence of A3G.

annealing, in order to ensure sensitivity to differences in annealing obtained when annealing with GagΔp6 or NCp7 in the presence or absence of A3G.

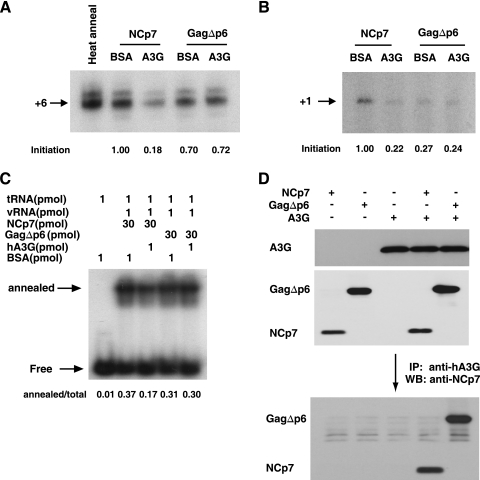

In Fig. 3A, the +6-nt RT extension products of  are resolved by using 6% 1D PAGE containing 7 M urea. Normalizing values to that obtained for the +6-nt extension from

are resolved by using 6% 1D PAGE containing 7 M urea. Normalizing values to that obtained for the +6-nt extension from  annealed by NCp7 in the absence of A3G, we see that +6-nt extension from

annealed by NCp7 in the absence of A3G, we see that +6-nt extension from  annealed by GagΔp6 is ca. 70% of that achieved by NCp7-facilitated annealing. The presence of A3G in the NCp7 annealing mixture reduces +6-nt extension to ca. 18% but has no effect upon initiation when added to a GagΔp6 annealing mixture. These results are similar to those obtained in Fig. 1C using RNA isolated from Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, in the presence or absence of A3G, although the inhibition of NCp7-facilitated annealing by A3G is greater in vitro (82% reduction) than in vivo (60% reduction). The fact that A3G can inhibit

annealed by GagΔp6 is ca. 70% of that achieved by NCp7-facilitated annealing. The presence of A3G in the NCp7 annealing mixture reduces +6-nt extension to ca. 18% but has no effect upon initiation when added to a GagΔp6 annealing mixture. These results are similar to those obtained in Fig. 1C using RNA isolated from Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, in the presence or absence of A3G, although the inhibition of NCp7-facilitated annealing by A3G is greater in vitro (82% reduction) than in vivo (60% reduction). The fact that A3G can inhibit  annealing with a 30-fold molecular excess of NCp7 and that inhibition of annealing requires an interaction of A3G with NCp7 (21) suggests that that A3G shows a preference for binding to NCp7 involved in

annealing with a 30-fold molecular excess of NCp7 and that inhibition of annealing requires an interaction of A3G with NCp7 (21) suggests that that A3G shows a preference for binding to NCp7 involved in  annealing, which might explain how only a limited number of A3G molecules in the virus can still cause inhibition of NCp7-faciltated annealing.

annealing, which might explain how only a limited number of A3G molecules in the virus can still cause inhibition of NCp7-faciltated annealing.

FIG. 3.

Effect of A3G on the GagΔp6- or NCp7-facilitated annealing of  to viral RNA in vitro. We determined that 1 pmol of synthetic viral genomic RNA and 1 pmol of purified human placental

to viral RNA in vitro. We determined that 1 pmol of synthetic viral genomic RNA and 1 pmol of purified human placental  were incubated with 30 pmol of either GagΔp6 or NCp7, in the presence of A3G or its absence (A3G replaced with BSA). (A and B) The resultin

were incubated with 30 pmol of either GagΔp6 or NCp7, in the presence of A3G or its absence (A3G replaced with BSA). (A and B) The resultin  /viral RNA complex was then used as a source of primer

/viral RNA complex was then used as a source of primer  /template viral genomic RNA in an in vitro reverse transcription system containing HIV-1 RT and deoxynucleotides, to produce either a 6-nt or a 1-nt extension of

/template viral genomic RNA in an in vitro reverse transcription system containing HIV-1 RT and deoxynucleotides, to produce either a 6-nt or a 1-nt extension of  , as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Shown are 1D PAGE patterns of

, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Shown are 1D PAGE patterns of  extended by either 6 (A) or 1 (B) nt, with quantitation of the results, relative to that of NCp7-facilitated annealing in the absence of A3G, shown below each lane. (C) The same annealing conditions as used for experiments in panels A and B were used with labeled

extended by either 6 (A) or 1 (B) nt, with quantitation of the results, relative to that of NCp7-facilitated annealing in the absence of A3G, shown below each lane. (C) The same annealing conditions as used for experiments in panels A and B were used with labeled  , and annealed versus free

, and annealed versus free  were resolved by native 1D PAGE. The fraction of total

were resolved by native 1D PAGE. The fraction of total  that was annealed is shown below each lane. (D) The interaction of 30 pmol of GagΔp6 or NCp7 with A3G. GagΔp6 or NCp7 was incubated with 1 pmol of A3G, and the ability of GagΔp6 or NCp7 to be coimmunoprecipitated with A3G, using anti-A3G, was detected by Western blots probed with anti-NCp7, as described in the text. The top two panels are Western blots of the reaction prior to immunoprecipitation, probed with anti-A3G or anti-NCp7, respectively. The lower panel is a Western blot of the anti-A3G immunoprecipitate from each reaction, probed with anti-NCp7. +6-nt and +1-nt experiments, and Western blots were repeated twice, while the electrophoretic band shift experiments were done three times.

that was annealed is shown below each lane. (D) The interaction of 30 pmol of GagΔp6 or NCp7 with A3G. GagΔp6 or NCp7 was incubated with 1 pmol of A3G, and the ability of GagΔp6 or NCp7 to be coimmunoprecipitated with A3G, using anti-A3G, was detected by Western blots probed with anti-NCp7, as described in the text. The top two panels are Western blots of the reaction prior to immunoprecipitation, probed with anti-A3G or anti-NCp7, respectively. The lower panel is a Western blot of the anti-A3G immunoprecipitate from each reaction, probed with anti-NCp7. +6-nt and +1-nt experiments, and Western blots were repeated twice, while the electrophoretic band shift experiments were done three times.

In Fig. 3B, the +1-nt RT extension products of  are resolved by using 6% 1D PAGE containing 7 M urea. Normalizing values to that obtained for the +1-nt extension from

are resolved by using 6% 1D PAGE containing 7 M urea. Normalizing values to that obtained for the +1-nt extension from  annealed by NCp7 in the absence of A3G, we see that the +1-nt extension from

annealed by NCp7 in the absence of A3G, we see that the +1-nt extension from  annealed by GagΔp6 is ca. 27% of that achieved by NCp7-facilitated annealing. The presence of A3G in the NCp7 annealing mixture reduces +1-nt extension to ca. 22% but has no effect upon initiation when added to a GagΔp6 annealing mixture. These results show the same pattern as those obtained in Fig. 1D using RNA isolated from Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−) Vif(−) virions, in the presence or absence of A3G.

annealed by GagΔp6 is ca. 27% of that achieved by NCp7-facilitated annealing. The presence of A3G in the NCp7 annealing mixture reduces +1-nt extension to ca. 22% but has no effect upon initiation when added to a GagΔp6 annealing mixture. These results show the same pattern as those obtained in Fig. 1D using RNA isolated from Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−) Vif(−) virions, in the presence or absence of A3G.

The +6-nt extension data shown in Fig. 1C or in Fig. 3A indicate that the reduced +1-nt extension for Gag-annealed  is due less to the amount of

is due less to the amount of  annealed and more to its weakened placement on the viral RNA (Fig. 2B and 3B). This is further indicated by the data shown in Fig. 3C, where, using the electrophoretic band shift method to resolve free

annealed and more to its weakened placement on the viral RNA (Fig. 2B and 3B). This is further indicated by the data shown in Fig. 3C, where, using the electrophoretic band shift method to resolve free  from annealed

from annealed  , we directly measured the amount of labeled

, we directly measured the amount of labeled  annealed by either NCp7 or GagΔp6, in the presence or absence of A3G. In our annealing conditions, NCp7, in the absence of A3G, anneals ca. 37% of

annealed by either NCp7 or GagΔp6, in the presence or absence of A3G. In our annealing conditions, NCp7, in the absence of A3G, anneals ca. 37% of  to the viral RNA, and there is a 55% reduction when A3G is present. GagΔp6 anneals ca. 84% as much of the

to the viral RNA, and there is a 55% reduction when A3G is present. GagΔp6 anneals ca. 84% as much of the  as is annealed by NCp7, with no change occurring when A3G is also present during annealing. Thus, the data using the electrophoretic band shift method strongly support the +6-nt extension data obtained in both Fig. 1C and 3A on the effects of NCp7, Gag, and A3G on

as is annealed by NCp7, with no change occurring when A3G is also present during annealing. Thus, the data using the electrophoretic band shift method strongly support the +6-nt extension data obtained in both Fig. 1C and 3A on the effects of NCp7, Gag, and A3G on  annealing.

annealing.

We have previously reported that the ability of A3G to inhibit the initiation of reverse transcription from  annealed by NCp7 in vitro depends upon the interaction of A3G with NCp7 (21). We therefore investigated whether the failure of A3G to inhibit GagΔp6-facilitated

annealed by NCp7 in vitro depends upon the interaction of A3G with NCp7 (21). We therefore investigated whether the failure of A3G to inhibit GagΔp6-facilitated  annealing in vitro resulted from the inability of A3G to interact with Gag. As described previously for measuring the NCp7/A3G interaction in vitro (21), equimolar amounts of either NCp7 or GagΔp6 were incubated with A3G, and their ability to be coimmunoprecipitated with anti-A3G (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) was detected on Western blots probed with goat anti-NCp7 (a gift from Louis Henderson, AIDS Vaccine Program). The results, shown in Fig. 3D, demonstrate that both NCp7 and GagΔp6 interact efficiently with A3G.

annealing in vitro resulted from the inability of A3G to interact with Gag. As described previously for measuring the NCp7/A3G interaction in vitro (21), equimolar amounts of either NCp7 or GagΔp6 were incubated with A3G, and their ability to be coimmunoprecipitated with anti-A3G (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) was detected on Western blots probed with goat anti-NCp7 (a gift from Louis Henderson, AIDS Vaccine Program). The results, shown in Fig. 3D, demonstrate that both NCp7 and GagΔp6 interact efficiently with A3G.

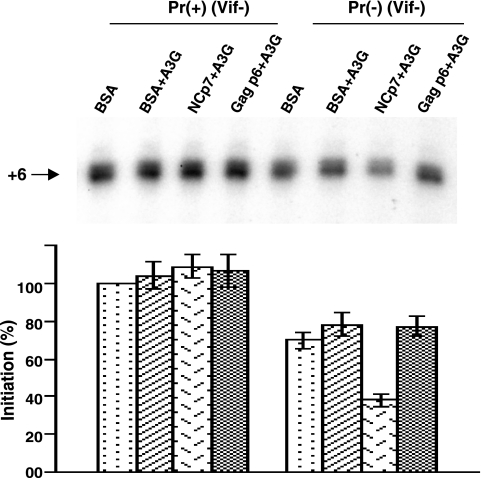

NCp7 rescue of Gag-facilitated  annealing is inhibited by A3G.

annealing is inhibited by A3G.

We have previously shown that transient exposure of BH10P− to NCp7 alone does not affect +6-nt extension, i.e., the amount of annealed  present, but does result in bringing +1 extension to wild-type levels, i.e., altering

present, but does result in bringing +1 extension to wild-type levels, i.e., altering  placement on the viral genome from that obtained by Gag to that obtained by NCp7 (11). We have investigated whether this conversion involves reannealing of

placement on the viral genome from that obtained by Gag to that obtained by NCp7 (11). We have investigated whether this conversion involves reannealing of  to the viral genomic RNA by determining whether it is sensitive to the presence of A3G, since A3G only inhibits annealing facilitated by NCp7, and not by Gag (Fig. 1C), and this inhibition requires A3G to be present during the annealing process (21). Total viral RNA was isolated from BH10 and BH10P−, and the RNAs were transiently exposed to BSA alone, or to A3G in the presence of either BSA, GagΔp6, or NCp7. The RNAs were then deproteinized and used in the in vitro reverse transcription system under conditions that extend the annealed

to the viral genomic RNA by determining whether it is sensitive to the presence of A3G, since A3G only inhibits annealing facilitated by NCp7, and not by Gag (Fig. 1C), and this inhibition requires A3G to be present during the annealing process (21). Total viral RNA was isolated from BH10 and BH10P−, and the RNAs were transiently exposed to BSA alone, or to A3G in the presence of either BSA, GagΔp6, or NCp7. The RNAs were then deproteinized and used in the in vitro reverse transcription system under conditions that extend the annealed  primer by 6 nt. 1D PAGE results and their graphic presentation of the amount of product made relative to BH10 RNA exposed only to BSA are shown in Fig. 4. The left side of the figure shows that once

primer by 6 nt. 1D PAGE results and their graphic presentation of the amount of product made relative to BH10 RNA exposed only to BSA are shown in Fig. 4. The left side of the figure shows that once  is annealed by NCp7 in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions, exposure to A3G, in the absence or presence of NCp7 or GagΔp6, has little effect upon the initiation of reverse transcription. On the other hand, as shown on the right side of the panel,

is annealed by NCp7 in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions, exposure to A3G, in the absence or presence of NCp7 or GagΔp6, has little effect upon the initiation of reverse transcription. On the other hand, as shown on the right side of the panel,  annealed by Gag in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions has a 50% reduction of initiation by A3G when in the presence of NCp7, relative to that obtained with BSA and A3G. Since A3G only reduces annealing by NCp7 during the process of annealing, and not after annealing has been accomplished (21), these results suggest that

annealed by Gag in Pr(−)Vif(−) virions has a 50% reduction of initiation by A3G when in the presence of NCp7, relative to that obtained with BSA and A3G. Since A3G only reduces annealing by NCp7 during the process of annealing, and not after annealing has been accomplished (21), these results suggest that  annealed by Gag can be displaced by, and reannealed by, NCp7, and allows for the possibility that in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses, annealing may be a two-step process, initially facilitated by Gag and then by NCp7.

annealed by Gag can be displaced by, and reannealed by, NCp7, and allows for the possibility that in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses, annealing may be a two-step process, initially facilitated by Gag and then by NCp7.

FIG. 4.

Ability of A3G to inhibit initiation of reverse transcription from  annealed in Pr(+)Vif(-) or Pr(−)Vif(-) viruses, after transient exposure of the annealed complex to A3G in the presence of either BSA, NCp7, or GagΔp6. Total viral RNA from BH10 or BH10P− was transiently exposed to A3G in the presence of either BSA, NCp7, or GagΔp6. After an additional deproteinization, the

annealed in Pr(+)Vif(-) or Pr(−)Vif(-) viruses, after transient exposure of the annealed complex to A3G in the presence of either BSA, NCp7, or GagΔp6. Total viral RNA from BH10 or BH10P− was transiently exposed to A3G in the presence of either BSA, NCp7, or GagΔp6. After an additional deproteinization, the  /viral RNA complex was used as a source of primer

/viral RNA complex was used as a source of primer  /template viral genomic RNA in an in vitro reverse transcription system containing HIV-1 RT and deoxynucleotides so as to measure +6-nt priming. The upper panel shows 1D PAGE patterns of

/template viral genomic RNA in an in vitro reverse transcription system containing HIV-1 RT and deoxynucleotides so as to measure +6-nt priming. The upper panel shows 1D PAGE patterns of  extended by 6 nt, and the lower panel shows quantitation of the results, relative to that of BH10 viral RNA transiently exposed to BSA alone. Experiments were performed twice.

extended by 6 nt, and the lower panel shows quantitation of the results, relative to that of BH10 viral RNA transiently exposed to BSA alone. Experiments were performed twice.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the ability of annealed  to initiate reverse transcription is studied using two reaction conditions that will allow either a +6-nt extension or a +1-nt extension of annealed

to initiate reverse transcription is studied using two reaction conditions that will allow either a +6-nt extension or a +1-nt extension of annealed  . Measurements of the +6-nt extension and the +1-nt extension reveal the amount of

. Measurements of the +6-nt extension and the +1-nt extension reveal the amount of  annealed and the ability of this annealed

annealed and the ability of this annealed  to initiate reverse transcription, respectively. In the conditions for +6-nt initiation, the concentrations of all dNTPs (including the [α-32P]GTP used) are not limiting for the +6-nt extension, while we have shown that the use of 0.16 μM dCTP is insufficient for obtaining the maximum 1-nt extension of

to initiate reverse transcription, respectively. In the conditions for +6-nt initiation, the concentrations of all dNTPs (including the [α-32P]GTP used) are not limiting for the +6-nt extension, while we have shown that the use of 0.16 μM dCTP is insufficient for obtaining the maximum 1-nt extension of  (11). We have interpreted changes in +6-nt initiation resulting from either the absence of protease activity or the presence of A3G as reflecting changes in the amount of

(11). We have interpreted changes in +6-nt initiation resulting from either the absence of protease activity or the presence of A3G as reflecting changes in the amount of  annealed. This view is supported by additional evidence. For example, the in vitro data using the electrophoretic band shift method to separate free from annealed

annealed. This view is supported by additional evidence. For example, the in vitro data using the electrophoretic band shift method to separate free from annealed  (Fig. 3C) supports the +6-nt extension differences between Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses in Fig. 2C by demonstrating that the amount of

(Fig. 3C) supports the +6-nt extension differences between Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses in Fig. 2C by demonstrating that the amount of  annealed by GagΔp6 is only slightly lower than that annealed by NCp7. Similarly, the 60% decrease in +6-nt extension that we observe when A3G is present in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions (Fig. 1C) is almost identical to the 58% decrease in the PBS occupancy measured in the same viral RNAs (Fig. 2B).

annealed by GagΔp6 is only slightly lower than that annealed by NCp7. Similarly, the 60% decrease in +6-nt extension that we observe when A3G is present in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions (Fig. 1C) is almost identical to the 58% decrease in the PBS occupancy measured in the same viral RNAs (Fig. 2B).

In comparing the initiation of reverse transcription in Pr(+)Vif(−) versus Pr(−)Vif(−) virions or the absence or presence of A3G in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses, +1-nt extensions always show greater differences than found with the +6-nt extensions (Fig. 1C and D). We interpret these greater differences to reflect greater sensitivity of the +1-nt extension to conformational differences of the annealing complex. For example, our interpretation that there is weaker binding of  in Pr(−)Vif(−) viral RNA is supported by the PBS occupancy data (Fig. 2B), showing that

in Pr(−)Vif(−) viral RNA is supported by the PBS occupancy data (Fig. 2B), showing that  annealed in a Pr(−)Vif(−) environment is more readily displaced. Thus, while the conditions in the +6-nt extension assay, including the high concentrations of dNTPs, are able to overcome the differences in annealing configurations between Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, allowing for more similar initiation of reverse transcription, these same conditions cannot overcome the inhibitory effect of A3G on initiation of reverse transcription in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions.

annealed in a Pr(−)Vif(−) environment is more readily displaced. Thus, while the conditions in the +6-nt extension assay, including the high concentrations of dNTPs, are able to overcome the differences in annealing configurations between Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions, allowing for more similar initiation of reverse transcription, these same conditions cannot overcome the inhibitory effect of A3G on initiation of reverse transcription in Pr(+)Vif(−) virions.

We have previously reported that A3G inhibits NCp7-facilitated  annealing in vitro only when A3G is present during the annealing step and that this inhibition requires an interaction between A3G and NCp7 (21). Since A3G does not inhibit Gag-facilitated

annealing in vitro only when A3G is present during the annealing step and that this inhibition requires an interaction between A3G and NCp7 (21). Since A3G does not inhibit Gag-facilitated  annealing in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses (Fig. 1C), it is possible that Gag plays no role in the annealing of

annealing in Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses (Fig. 1C), it is possible that Gag plays no role in the annealing of  in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. However, the results in Fig. 4 and those previously reported (11) are consistent with a possible role for Gag in

in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. However, the results in Fig. 4 and those previously reported (11) are consistent with a possible role for Gag in  annealing in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. Thus, we have previously shown that transient exposure of viral RNA from BH10P− to NCp7 brings annealing to wild-type levels (11), while the results in Fig. 4 show that transient exposure of viral RNA from Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses to NCp7 and A3G indicate that A3G can inhibit this rescue. These data suggest that after

annealing in Pr(+)Vif(−) viruses. Thus, we have previously shown that transient exposure of viral RNA from BH10P− to NCp7 brings annealing to wild-type levels (11), while the results in Fig. 4 show that transient exposure of viral RNA from Pr(−)Vif(−) viruses to NCp7 and A3G indicate that A3G can inhibit this rescue. These data suggest that after  annealing by Gag, NCp7 can displace the

annealing by Gag, NCp7 can displace the  and reanneal it to the viral RNA, and this reannealing by NCp7 is subject to A3G inhibition. Although there is no direct proof that Gag actually participates in

and reanneal it to the viral RNA, and this reannealing by NCp7 is subject to A3G inhibition. Although there is no direct proof that Gag actually participates in  annealing in wild-type viruses, an advantage to having Gag participate in this process is that Gag has been shown to have a binding preference for stem-loops in the 5′ region of viral RNA near the region where

annealing in wild-type viruses, an advantage to having Gag participate in this process is that Gag has been shown to have a binding preference for stem-loops in the 5′ region of viral RNA near the region where  binds, a preference not exhibited by mature NCp7 (13). Gag might thus be able to facilitate a nucleation step that brings

binds, a preference not exhibited by mature NCp7 (13). Gag might thus be able to facilitate a nucleation step that brings  and the largely, if not entirely, single-stranded PBS sequences together, while NCp7 may be able to facilitate, in addition to nucleation steps, other required changes in viral RNA such as denaturation of double-stranded regions in viral RNA (such as the primer activation signal [3, 4]) and in

and the largely, if not entirely, single-stranded PBS sequences together, while NCp7 may be able to facilitate, in addition to nucleation steps, other required changes in viral RNA such as denaturation of double-stranded regions in viral RNA (such as the primer activation signal [3, 4]) and in  (such as disruption of the D/TΨC loop interaction [24, 46]), that have been reported to be involved in annealing. Other changes in the conformation of viral RNA bound with Gag or NCp7 that might play a role in availability of RNA sequences for annealing with

(such as disruption of the D/TΨC loop interaction [24, 46]), that have been reported to be involved in annealing. Other changes in the conformation of viral RNA bound with Gag or NCp7 that might play a role in availability of RNA sequences for annealing with  have been suggested from the observation that viral RNA isolated from protease-negative virions is less thermostable than wild-type viral RNA (17). In addition to problems with RNA conformation, one cannot exclude the possibility that proteins other than nucleocapsid may be involved in promoting

have been suggested from the observation that viral RNA isolated from protease-negative virions is less thermostable than wild-type viral RNA (17). In addition to problems with RNA conformation, one cannot exclude the possibility that proteins other than nucleocapsid may be involved in promoting  annealing. For example, connection domain sequences in RT have been shown to be required for the annealing of

annealing. For example, connection domain sequences in RT have been shown to be required for the annealing of  in vivo (12), and a protein complex involved in annealing may require a particular configuration that is achieved better with NCp7 than with Gag.

in vivo (12), and a protein complex involved in annealing may require a particular configuration that is achieved better with NCp7 than with Gag.

A recent study, using permeabilized virions to study reverse transcription, reported that A3G does not affect  annealing (5). The experiment was performed by using RT-PCR to amplify extended

annealing (5). The experiment was performed by using RT-PCR to amplify extended  present in virions with or without A3G and concluded that the same amount of

present in virions with or without A3G and concluded that the same amount of  was extended in both viral types. However, reverse transcription in permeabilized viruses is problematic, since reverse transcription is naturally restricted in virions, and the cause(s) of this restriction remain unknown. Even with permeabilization of the envelope to allow access to exogenous dNTPs, reverse transcription in virions is inefficient and of low processivity, a point not noted by these authors. Other evidence suggests that proviral DNA synthesis probably depends upon the structure and stability of the viral core (reviewed in reference 43). Thus, PCR in permeabilized virions is generally required to see the DNA products and, when radioactive products are seen after a long incubation periods, their resolution using 1D PAGE shows smears, rather than discrete bands, with very little full-length strong-stop minus-strand synthesis (5, 19, 50, 51). In HIV-1, restriction of reverse transcription is not limited by the annealed

was extended in both viral types. However, reverse transcription in permeabilized viruses is problematic, since reverse transcription is naturally restricted in virions, and the cause(s) of this restriction remain unknown. Even with permeabilization of the envelope to allow access to exogenous dNTPs, reverse transcription in virions is inefficient and of low processivity, a point not noted by these authors. Other evidence suggests that proviral DNA synthesis probably depends upon the structure and stability of the viral core (reviewed in reference 43). Thus, PCR in permeabilized virions is generally required to see the DNA products and, when radioactive products are seen after a long incubation periods, their resolution using 1D PAGE shows smears, rather than discrete bands, with very little full-length strong-stop minus-strand synthesis (5, 19, 50, 51). In HIV-1, restriction of reverse transcription is not limited by the annealed  present, since initiation of DNA synthesis from this tRNA occurs after infection. If only a small fraction of the annealed

present, since initiation of DNA synthesis from this tRNA occurs after infection. If only a small fraction of the annealed  is extended in permeabilized viruses (i.e., 5 to 10%), one would not be able to detect a 50% reduction in annealed

is extended in permeabilized viruses (i.e., 5 to 10%), one would not be able to detect a 50% reduction in annealed  in virions by comparing the amount of

in virions by comparing the amount of  extended in virions containing or lacking A3G. These authors also reported that A3G reduced elongation of minus-strand DNA synthesis in permeabilized viruses. Their result differs from another report that showed a lack of effect of A3G on HIV-1 DNA elongation occurring in the cytoplasm of infected cells (37). Perhaps the finding of Mougel at al. (43) is due to the fact that elongation in permeabilized virions is already very impaired (i.e., low processivity of reverse transcription) even in the absence of A3G, and A3G is acting on this impaired system.

extended in virions containing or lacking A3G. These authors also reported that A3G reduced elongation of minus-strand DNA synthesis in permeabilized viruses. Their result differs from another report that showed a lack of effect of A3G on HIV-1 DNA elongation occurring in the cytoplasm of infected cells (37). Perhaps the finding of Mougel at al. (43) is due to the fact that elongation in permeabilized virions is already very impaired (i.e., low processivity of reverse transcription) even in the absence of A3G, and A3G is acting on this impaired system.

Another recent report (31) observed that A3G does not inhibit in vitro annealing of  to viral RNA, and this report is of interest for the following reason. Using an electrophoretic band shift assay to measure the amount of radioactive

to viral RNA, and this report is of interest for the following reason. Using an electrophoretic band shift assay to measure the amount of radioactive  annealed to viral RNA, their reaction conditions were optimized to achieve 100%

annealed to viral RNA, their reaction conditions were optimized to achieve 100%  annealing, while our conditions never achieved more than 40 to 50% annealing. However, our in vitro annealing conditions achieved results similar to what we observed studying

annealing, while our conditions never achieved more than 40 to 50% annealing. However, our in vitro annealing conditions achieved results similar to what we observed studying  that had been annealed in vivo, i.e., A3G inhibits NCp7-facilitated annealing but not Gag-facilitated annealing. We would conclude from this comparison that conditions in vivo are not optimized for

that had been annealed in vivo, i.e., A3G inhibits NCp7-facilitated annealing but not Gag-facilitated annealing. We would conclude from this comparison that conditions in vivo are not optimized for  annealing and therefore are subject to more regulation by A3G. Supporting this are the facts that (i) the PBS occupancy by

annealing and therefore are subject to more regulation by A3G. Supporting this are the facts that (i) the PBS occupancy by  annealed in vivo to viral RNA is only 67% (Fig. 2B) and (ii) increasing the amount of

annealed in vivo to viral RNA is only 67% (Fig. 2B) and (ii) increasing the amount of  incorporated into virions results in a near doubling of the

incorporated into virions results in a near doubling of the  annealed (18).

annealed (18).

The in vitro reverse transcription system used here with isolated viral RNA as the source of primer  annealed to viral RNA template has been designed so that the amount of reverse transcription occurring reflects the amount primer

annealed to viral RNA template has been designed so that the amount of reverse transcription occurring reflects the amount primer  annealed to the viral RNA and/or the conformation of the annealed complex. Several pieces of data support the assumption that the isolated annealed primer

annealed to the viral RNA and/or the conformation of the annealed complex. Several pieces of data support the assumption that the isolated annealed primer  /viral RNA complex used here reflects its annealing state achieved in vivo. The

/viral RNA complex used here reflects its annealing state achieved in vivo. The  /genomic RNA complex is thermally stable, i.e., dissociating at temperatures only above 70°C (47), and the free

/genomic RNA complex is thermally stable, i.e., dissociating at temperatures only above 70°C (47), and the free  present in total viral RNA does not anneal to genomic RNA under reverse transcription conditions, even in the presence of nucleocapsid (11). Second, deproteinized total viral RNA isolated from virions containing wild-type or mutant proteins has revealed different degrees of

present in total viral RNA does not anneal to genomic RNA under reverse transcription conditions, even in the presence of nucleocapsid (11). Second, deproteinized total viral RNA isolated from virions containing wild-type or mutant proteins has revealed different degrees of  annealing (27), which must reflect differences occurring in the viruses since the total viral RNA used in the reverse transcription reaction no longer contains these viral proteins. An example of this that is presented here are the differences in annealing we find associated with Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions. Third, although deproteinized RNA is used in this assay, the continued presence of nucleocapsid protein is not required once nucleocapsid-induced effects upon

annealing (27), which must reflect differences occurring in the viruses since the total viral RNA used in the reverse transcription reaction no longer contains these viral proteins. An example of this that is presented here are the differences in annealing we find associated with Pr(+)Vif(−) and Pr(−)Vif(−) virions. Third, although deproteinized RNA is used in this assay, the continued presence of nucleocapsid protein is not required once nucleocapsid-induced effects upon  annealing have occurred. Thus, the transient exposure to NCp7 of viral RNA from Pr(−) HIV-1 restores

annealing have occurred. Thus, the transient exposure to NCp7 of viral RNA from Pr(−) HIV-1 restores  annealing to that characteristic for Pr(+) viruses (11) (Fig. 4).

annealing to that characteristic for Pr(+) viruses (11) (Fig. 4).

We have reported that the amount of  annealing in a viral population is proportional to the amount of viral