Abstract

Ultrahigh-resolution adaptive optics–optical coherence tomography (UHR-AO-OCT) instrumentation allowing monochromatic and chromatic aberration correction was used for volumetric in vivo retinal imaging of various retinal structures including the macula and optic nerve head (ONH). Novel visualization methods that simplify AO-OCT data viewing are presented, and include co-registration of AO-OCT volumes with fundus photography and stitching of multiple AO-OCT sub-volumes to create a large field of view (FOV) high-resolution volume. Additionally, we explored the utility of Interactive Science Publishing by linking all presented AO-OCT datasets with the OSA ISP software.

1. Introduction

Enabled by recent progress in the development of optical coherence tomography (OCT) [1-4], including its Fourier/spectral-domain variation [5-11], several companies have introduced clinical OCT instruments for ophthalmic imaging. This has resulted in rapid growth of OCT use for monitoring progression and treatment of many retinal diseases in everyday clinical practice. What makes OCT so attractive is its high sensitivity (ability to measure weak backscattered signals), high acquisition speed (allowing volumetric imaging within seconds) and high axial resolution tomographic cross-sections. The retinal organization of similar cell types arranged in almost transparent horizontal layers is conducive to identification of pathogenesis imaged in vivo with this technique. The well-defined spatial organization of the retina also invites complex image processing, including quantitative analysis of segmented layers, and registration with other clinical imaging methods. With deeper penetration of the optic nerve head (ONH) it also permits a study of ganglion cell axons as they begin their projection to subcortical and cortical projection sites.

Lateral resolution in clinical OCT systems is, however, insufficient for imaging of individual cellular structures. To overcome this limitation one would have to increase lateral resolution by increasing the numerical aperture (NA) of the imaging system. This can be achieved by increasing the diameter of the OCT imaging beam at the eye's pupil. Unfortunately due to imperfections in the optics of the eye, this approach yields only a small improvement in lateral resolution. For most subjects, if one increases the size of the imaging beam by over 2 mm at the eye's pupil, lateral resolution deteriorates [12]. Correcting ocular aberrations in real time can overcome this limitation and further improve lateral resolution. This can be achieved by implementing adaptive optics (AO) to measure and correct the wavefront error of the eye. The value of high-resolution, AO-based imaging has been demonstrated in fundus cameras (flood illuminated ophthalmoscopes) [13-15] and scanning laser ophthalmoscopes [16-18] to visualize cellular retinal structures. However, due to the limited axial resolution and sensitivity of these instruments, they have been mainly used in imaging highly reflective structures such as cone photoreceptors, micro-capillaries and nerve fiber bundles visualized over a narrow depth of focus without insight into axial structure. To overcome this limitation and to gain further insights into volumetric retinal features at cellular resolution, AO has been incorporated into various OCT systems [19-29]. However volumetric resolution and visibility of retinal details achieved by those instruments have been limited either by axial or lateral resolution. Recently, the first two papers reporting AO-OCT with isotropic volumetric resolution (∼3 μm) [30-31] have been published. To achieve this resolution, AO combined with ultrahigh-resolution (UHR)-OCT requires additional optical elements to compensate for the eye's longitudinal chromatic aberration (LHA).

In this paper, we present for the first time volumetric images of various retinal structures acquired with the UC Davis UHR-AO-OCT system [30] allowing monochromatic and chromatic aberration correction. Novel methods to simplify AO-OCT data visualization, including co-registration of AO-OCT volumes with fundus photography and stitching of multiple AO-OCT sub-volumes to create large field-of-view (FOV) high-resolution volumes are presented. Additionally, we have taken advantage of the OSA “Interactive Science Publishing” by linking all the presented AO-OCT datasets to make possible data visualization with OSA ISP software.

2. Materials and methods

The UHR-AO-OCT used in this paper for retinal volumetric imaging has been described in detail in our recent publication [30]. Additionally, different strategies of acquiring volumetric AO-OCT datasets can be found in our previous papers [23,24,26]. Here, we focus mainly on the new aspects of volumetric imaging with UHR-AO-OCT. These mainly include image acquisition and volumetric data manipulation and visualization.

2.1. UHR-AO-OCT instrument

The light source used for both UHR-OCT and wavefront sensing is a superluminescent diode (Superlum BroadLighter T840-HP). This permits ∼3.5 μm axial resolution in retinal tissue. The measured light level at the entrance pupil of the subject's eye is maintained below 450 μW. In our current configuration, the imaging beam diameter is approximately 6.6 mm at the subject's pupil. An AO system using two deformable mirrors (DMs) for better AO performance, has been introduced into the OCT sample arm to allow correction of the subject's ocular aberrations over this pupil size. With good AO correction, lateral resolution is similar to axial resolution, resulting in an isotropic volumetric point-spread function. The OCT-control unit drives vertical and horizontal scanners with programmable scanning patterns (maximum field of view of 4°), acquires ∼18k lines/s for 50 μs line exposures (there is ∼6 μs/line of read out and processing time) and displays 32 frames/s with 500 lines/frame of OCT data. An AO-control system operates the AO closed-loop correction at a rate of 16 Hz. The same light source is used for both wavefront sensing and imaging to permit the OCT data to be saved without interfering with the AO system operation. In the design of our AO-OCT sample arm, all key optical components were at planes conjugate to the pupil of the eye, including vertical and horizontal scanning mirrors, wavefront correctors (AOptix Technologies Bimorph DM and Boston Micromachines Corp. MEMS DM), the Hartmann-Shack wavefront sensor and the fiber collimator for light delivery.

2.2. Volumetric data acquisition

Several different 3D raster scanning modes have been used to acquire the images presented in this paper. In our standard sampling acquisition mode [100 B-scans (1000 lines/B-scan)], 100,000 A-lines are acquired in about T = 5.5 s to image one volume. This grid is usually used to acquire “larger” AO-OCT volumes (1 mm × 1 mm) where equidistant lateral sampling is not critical (visualization of capillaries or nerve fiber bundles). An alternative commonly used sampling grid [300 B-scans (250 lines/B-scan)] has a shorter acquisition time, T = 4.2 s. This grid is usually used to acquire “small” AO-OCT volumes (250 μm × 300 μm) where equidistant lateral sampling is important (e.g., for visualization of cellular retinal structures such as photoreceptors). Unfortunately, despite head restraint and implementation of B-scan co-registration, it is not possible to correct all the distortions introduced by eye motion. This can be observed as disruptions in retinal vasculature on the OCT fundus image (that is created from volumetric data as a superposition of the voxel values in the axial direction). One way to minimize this problem is by tracking and correcting for retinal motion in real time during acquisition [32,33] or in post-processing [34]. Application of the first method would require construction of a more complex and more costly imaging instrument. The second method requires fast transverse (en-face) image acquisition to track retinal motion that is usually achieved by an SLO, but could also be achieved with future ultrahigh-speed OCT. We do not discuss those issues in detail in this paper. Table 1 compares acquisition times and sampling densities of the two volume acquisition schemes that were tested in this paper.

Table 1.

Comparison of Volume Acquisition Times and Lateral Sampling for Two Grids

| Volumetric Acquisition | Sampling Grid | Lateral Sampling Distance | Acquisition Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Large” volume | 100 B-scans; 1000 lines/B-scan (100,000 lines) |

Δx = 1 μm; Δy = 10 μm; | T = 5.5 s |

| “Small” volume | 300 B-scans; 250 lines/B-scan (75,000 lines) |

Δx = 1 μm; Δy = 1 μm; | T = 4.2 s |

2.2.1. Acquisition of large FOV using sub-volumes

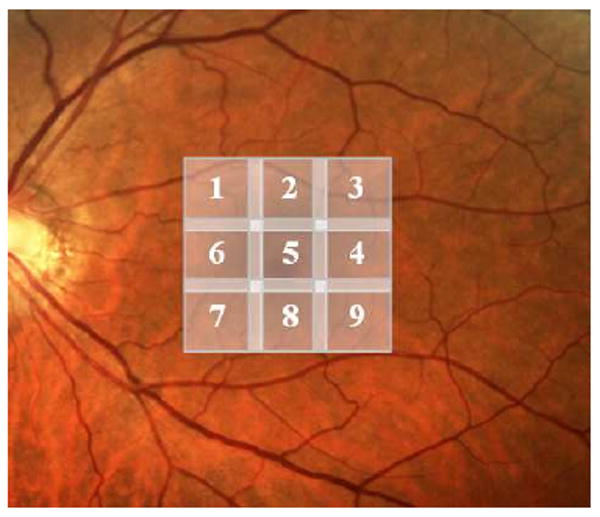

To enhance the impact of our UHR-AO-OCT instrument for clinical application, we modified our visualization software to allow stitching of multiple volumetric datasets to create larger FOV high-resolution retinal volumes rather than displaying only one AO-OCT volume acquired at a pre-set sampling location [32]. In an AO-OCT instrument the size of the single volume is restricted by either of two factors: maximum lateral scanning area of the system or the isoplanatic field of a given eye. For our current system (imaging wavelengths and pupil diameter) it's approximately 2-3°, thereby setting the maximum area that could be covered by a single AO-OCT volume (without compromising image resolution). In our previous work [26] we proposed a 1×1 mm 3D raster scanning mode that acquires 100 B-scans (1000 lines/B-scan) in about 5.5 s (with line acquisition exposure of 50 μs) as adequate for “large” AO-OCT volume imaging. As already mentioned, such volumetric sampling is not dense enough to reveal volumetric cellular structures. Nevertheless, it allows clear visualization of many interesting retinal features including microcapillaries and nerve fiber bundles. Its size, however, is still small compared to the FOV of standard clinical instruments. Therefore, we used this scanning mode to acquire multiple volumes that could be combined to create larger FOV AO-OCT volumes for clinical applications. Since each single AO-OCT sub-volume was set to cover about 1×1 mm (for the case of large FOV sub-volume acquisition) the spacing between centers of two consecutive sub-volumes should not exceed 70-80% of sub-volume width (i.e., 700-800 μm). This overlap of multiple sub-volumes is essential for later sub-volume co-registration and stitching. In order to change the location of a sub-volume we change the location of the fixation point. This is presently the only way of changing the location of the sub-volumes since each single sub-volume uses the whole scanning range of our instrument. The only difference between this sub-volume acquisition and our regular data acquisition mode is the spacing between fixation points resulting in overlap among sub-volumes. Figure 1 illustrates the AO-OCT scanning areas used in sub-volumetric measurements with an acquisition scheme using nine sub-volumes.

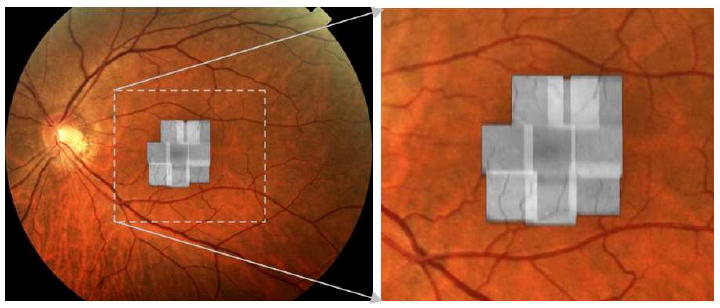

Fig. 1.

An example of AO-OCT scanning areas used for creating larger FOV volume (based on the acquisition of nine sub-volumes). Numbers on the sub-volumes refer to the order in which they were acquired. Fundus photo is used for reference.

2.3. Manual stitching and visualization of sub-volumes

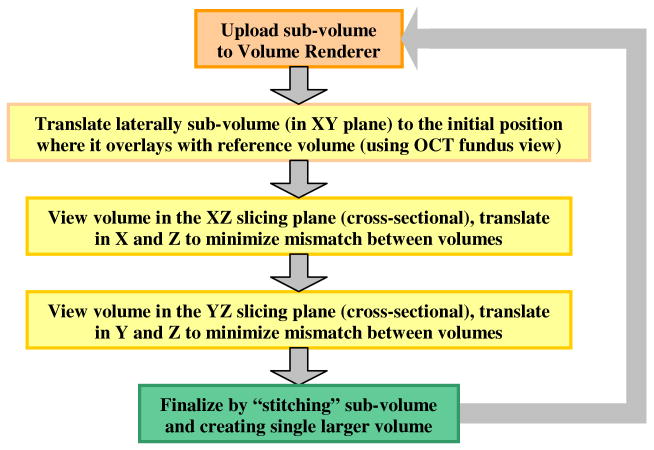

To stitch sub-volumes we have incorporated additional functionality into our OCT volume renderer, described previously [36], to permit independent manipulation of each sub-volume (free translation, one at a time in three dimensions) and viewing of the resulting volume and its cross-sectional slices in real time. This allows for accurate and timely stitching of several sub-volumes within minutes. After proper positioning of sub-volumes data can then be “stitched” and saved as a single large volume. This step is then repeated until a large FOV volume consisting of all sub-volumes is created. The figure below shows a simplified flow chart of our manual sub-volume registration and stitching procedure.

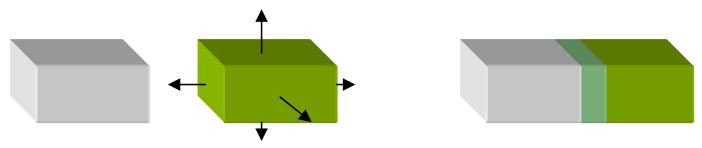

There are various ways of combining the data in the overlapping regions (usually by 10-15%) of two sub-volumes. We currently choose the maximum value of two overlaying voxels as the value of the resulting voxel in order to preserve the prominent characteristics of each volume. This also enhances artifacts if sub-volumes are not aligned properly and therefore helps to co-register them by minimizing it. The figure below shows a schematic of the manual volume manipulation allowed during sub-volume registration.

2.3.1. Co-registration of AO-OCT volumetric datasets with other imaging modalities

As already pointed out, due to the growing reliance on Fourier-domain OCT in ophthalmological diagnoses, it is increasingly important to be able to compare results obtained with this instrument to other clinical imaging systems. This task is trivial if the OCT instrument itself is a part of such a system, but no system combines all the relevant clinical images that may be needed for a given subject. Thus, cross-platform registration needs to be implemented. This problem is quite complex as the scaling and distortions between imaging platforms may not be linear. In this work, we implemented simplified co-registration using only scaling, translation and rotation of co-registered images. Similarly to the aforementioned stitching and visualization of sub-volumes, this functionality has been incorporated into our OCT volume renderer [36] for manipulation and viewing of a co-registered image on the corresponding OCT volume, its OCT fundus image and cross-sectional slices. In our current system we can freely scale, rotate and translate a fundus photo in three dimensions. Our system currently allows this transformation to be manipulated directly or by matching points from the fundus photo to a two-dimensional projection of the OCT dataset (OCT fundus). This point correlation approach operates solely in a two-dimensional domain, thus only two sets of correlated points are needed to completely define this transformation. Such manipulation is accomplished with the co-registered image only (OCT data remains unchanged). This approach allows the segmentations and annotations (any drawings / marks made on OCT cross-sectional planes) imposed on the OCT volume to be displayed on the co-registered fundus photo. Figure 4 shows a schematic of the image manipulation allowed during this registration process.

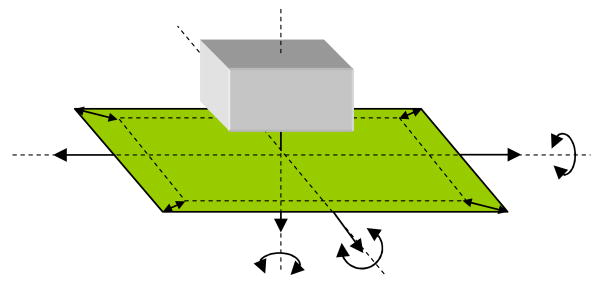

Fig. 4.

Schematic of the manipulation allowed during co-registration of the fundus photo (green rectangle) with the OCT volume.

3. Results and discussion

In this section, several examples of retinal structures acquired with our UHR-AO-OCT system offering high isotropic resolution of 3.5μm are presented.

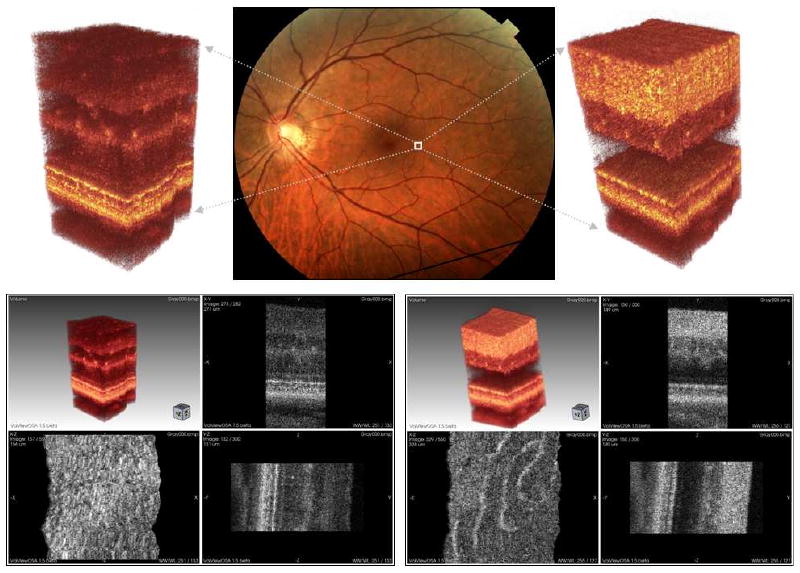

3.1. UHR-AO-OCT retinal imaging

As an example of UHR-AO-OCT imaging at cellular resolution, two volumes of the retina acquired with a small volume scanning grid with two different settings of the focusing plane [23] are shown in Fig. 4. Both volumes have been acquired over 250 × 300 μm with equidistant lateral sampling steps of 1 μm. Depending on the location of the AO system focus, different retinal structures can be observed. Thus, with the focus set at outer retinal layers the volumetric structure of the cone photoreceptor matrix is recognizable, but the inner retinal layers appear blurred and less reflective due to their location outside the focus. If the AO focus is shifted towards the inner retina, one can observe nerve fiber bundles, microcapillaries and some variation in signal intensity (besides speckles) from the ganglion cell layer and both plexiform layers. In this case, photoreceptor layers are blurred (out of focus). A clear increase in signal intensity measured from inner retinal layers can be observed if compared to images obtained with different focus settings. The retinal location where both volumes were acquired is shown on the corresponding fundus photo. A visualization of retinal volumes with our custom Volume Renderer is shown on both sides of the fundus photo. Additionally, we show a screenshot of the same volumes from the OSA ISP software with links to the volumetric visualizations.

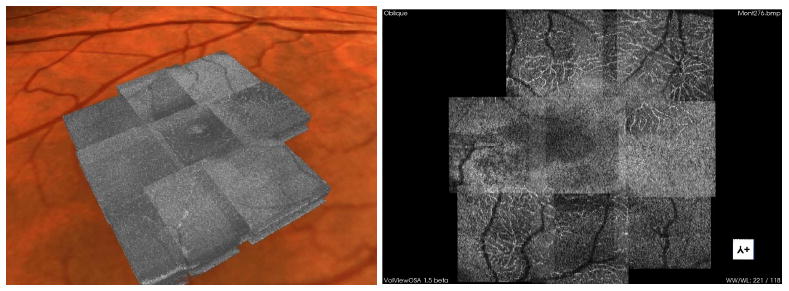

UHR-AO-OCT volumetric retinal imaging with large FOV volumes, exceeding our current system FOV of ∼ 1mm, similarly to other AO imaging modalities (that also have a small field of view), can be achieved by acquiring multiple volumes and merging them into a “montage.” As an example, Fig. 6 shows a set of nine volumes acquired (as described in paragraph 2.2.1) covering approximately 2.5 × 2.5 mm area on the retina. The figure shows a screenshot from our custom volume renderer with an OCT fundus view of the final volumetric montage with co-registered fundus photo. Each sub-volume covers 1 × 1 mm and was acquired using the large volume acquisition mode. Registration of the sub-volumes and subsequent co-registration between the resulting large FOV AO-OCT volume and fundus photo was achieved by manipulating this data through the user friendly interface of our volume rendering software. The large FOV is likely to facilitate clinical and scientific applications of AO-OCT.

Fig. 6.

OCT fundus montage created with our volume renderer of nine stitched AO-OCT 1 × 1 mm sub-volumes acquired with focus set on inner retinal layers.

It can be seen that small retinal vessels can be used as anchor points for co-registration of AO-OCT volumes to fundus photos. As a result of this co-registration one can interactively view with our volume renderer both the AO-OCT volume and fundus photo to achieve better visualization and localization of the retinal features between two imaging modalities. As an example of the volumetric view of a large FOV AO-OCT volume, Fig. 7 shows a screenshot of an image generated with our volume renderer. It can be seen that even though vertical spacing between consecutive B-scans is approximately 10 μm, microscopic retinal features can be recognized easily.

Fig. 7.

Visualization of the large FOV AO-OCT volume (from Fig. 5). Left, movie of the volume with co-registered fundus photo generated with our custom visualization software (Media 1). Right, screenshot from OSA ISP with the slicing plane view of the large FOV AO-OCT volume (View 3). Note the clear visualization of microcapillaries and foveal avascular zone when altering the location of the slicing plane.

We submit that the creation and display of large FOV AO-OCT volumes greatly improves the potential clinical impact of our AO-OCT system. This functionality will be further enhanced when combined with more automated data acquisition and stitching procedures to be developed in the future.

3.2. AO-OCT ONH imaging

To illustrate the use of AO-OCT for visualization of retinal structures outside the fovea, we imaged the optic nerve head (ONH) of a healthy 50-year-old volunteer. The AO-OCT system used for ONH imaging was an earlier version of the UHR-AO-OCT mentioned above. The two main differences are: reduced axial resolution (6 μm) and fixed wavefront correction during imaging. Both were dictated by current constraints of our UHR-AO-OCT instrument. The reduction of axial resolution was forced by the presence of transverse chromatic aberrations (TCA). This aberration is responsible for lateral blur of the imaging spot and increased with spectral bandwidth and eccentricity of the imaged structure [30,37]. Thus, reduction of spectral bandwidth helped to limit the degrading impact of TCA on image quality. Imaging with fixed wavefront correction was forced by our AO-OCT imaging scheme where the same light is used for both imaging and wavefront sensing. Thus, while imaging structures like the ONH, with variation in axial location, no stable reference plane (in depth) can be used by the wavefront sensor, thereby reducing the stability of AO correction. To overcome this problem we closed our AO loop while scanning the imaging beam outside the ONH and then, after fixing the wavefront corrector, asked the subject to look in the direction allowing one to image the region of interest in the ONH.

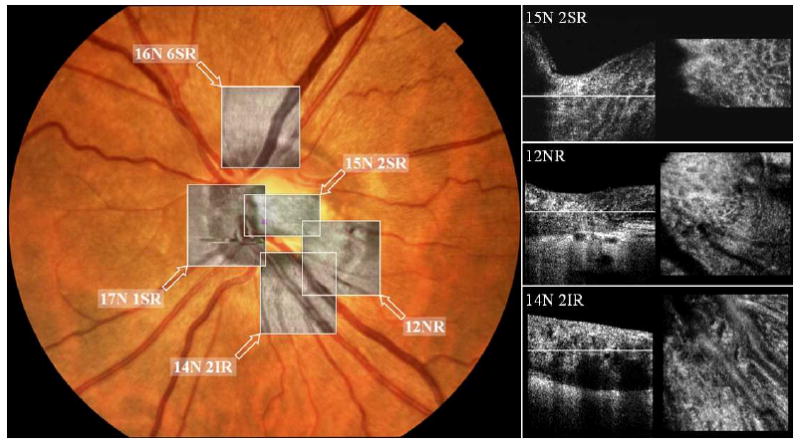

Figure 8 shows the locations of multiple AO-OCT volumes acquired over an ONH region superimposed on a conventional fundus photograph of the same region. Multiple microscopic structures including lamina cribosa and blood vessels are easily recognizable. Links to the same AO-OCT volumes visualized with the OSA ISP software are provided as well.

Fig. 8.

Visualization of the ONH microscopic structures imaged with AO-OCT. Left, screenshot from our custom volume renderer after co-registration of five 3D AO-OCT datasets with fundus photo. Right, screenshots from movies showing B-scan and cross-sectional view [26] of three AO-OCT volumes shown on the left: 15N 2SR (Media 2), 12NR (Media 3), and 14N 2IR (Media 4). White lines on the B-scans correspond to the depth of the C-scans reconstructed from the same volume. Multiple microscopic structures including lamina cribosa and blood vessels are easily recognizable. All the volumes can be accessed and viewed with OSA ISP: 12NR (View 4), 14N 2IR (View 5), 15N 2SR (View 6), 17N 1SR (View 7), and 16N 6SR (View 8). Note that the volume acquired at 17N 1SR has motion distortion that could not be properly corrected.

Several features that may be used in the diagnosis of retinal diseases can be visualized and recognized clearly, including the microscopic morphology of the ONH rim and lamina cribosa. Squares superimposed on the fundus photograph of the subject's ONH are used to denote the locations where high-resolution AO-OCT images were acquired. Single B-scans from full volumes and reconstructed C-scans are also presented.

4. Conclusions

The utility of UHR-AO-OCT volumetric imaging for research and clinical application is still being evaluated. Image understanding seldom follows immediately from hardware development. Instead, new imaging modalities may require not only clinical testing but novel visualization methods, especially with volumetric data providing unfamiliar views to clinicians. We have shown several examples of the application of our UHR-AO-OCT system for imaging volumetric retinal structures at cellular resolution. As can be seen in the two examples, AO-OCT helps to visualize volumetric micro-morphology of retinal structures that should allow monitoring disease progression or treatment on a microscopic scale. It also may provide a unique tool for the study of retinal disease as structures may now be seen that were previously available only through histological methods and necessarily at only one time point in the course of the disease.

Our current UHR-AO-OCT volumes suffer from retinal motion artifacts that cannot be removed due to insufficient acquisition speed. This of course translates into motion artifacts on the stitched sub-volumes making it more difficult to co-register. Additionally, since retinal eccentricity is chosen by changing the location of a fixation point, a nonlinear distortion of the AO-OCT volumes can be observed between sub-volumes. This effect creates additional artifacts on stitched volumes. In this case, more complex sub-volume manipulation (beyond simple translation) would be necessary to limit these artifacts.

Fig. 2.

A simple flow chart representing the process of sub-volume co-registration and stitching.

Fig. 3.

Left, schematic of the volume manipulation allowed during manual volume stitching in our volume renderer. Right, resulting volume with common voxels.

Fig. 5.

UHR-AO-OCT volume of the retinal structures acquired over 0.25 × 0.3 mm area on the 4.5 deg temporal retina (TR). Top row: left, visualization of the data acquired with UHR-AO-OCT system focus set on photoreceptor layers; center, fundus photo with marked location of the acquired volumes; right, visualization of the data acquired with UHR-AO-OCT system focus set on inner retinal layers. Bottom row: left, screenshot from OSA ISP with the UHR-AO-OCT volume with focus set on photoreceptor layers (View 1); right, screenshot from OSA ISP with the UHR-AO-OCT volume and focus set on inner retina layers (View 2). Multiple microscopic and cellular structures can be recognized clearly (including photoreceptors seen on the lower left panel and microcapillaries seen on the lower right panel).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Steven M. Jones, Diana Chen and Scot S. Olivier from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory for providing AO support. Help from Joseph A. Izatt from the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Duke University Durham, North Carolina. and Bioptigen Inc., Durham, North Carolina for providing OCT data acquisition software is appreciated. Alfred Fuller was supported by a Student Employee Graduate Research Fellowship (SEGRF) via Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Julia W. Evans has been partially supported by funding from the National Science Foundation. The Center for Biophotonics, an NSF Science and Technology Center, is managed by the University of California, Davis, under Cooperative Agreement No. PHY 0120999. This research was supported by the National Eye Institute (grant EY 014743).

Footnotes

Datasets associated with this article are available at http://hdl.handle.net/10376/1411.

References and links

- 1.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, Flotte MR, Gregory K, Puliafito CA. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swanson EA, Izatt JA, Hee MR, Huang D, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. In vivo retinal imaging by optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 1993;18:1864–1866. doi: 10.1364/ol.18.001864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fercher AF, Hitzenberger CK, Drexler W, Kamp G, Sattmann H. In vivo optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:113–114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71762-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drexler W, Morgner U, Ghanta RK, Kartner FX, Schuman JS, Fujimoto JG. Ultrahigh-resolution ophthalmic optical coherence tomography. Nat Med. 2001;7:502–507. doi: 10.1038/86589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fercher AF, Hitzenberger CK, Kamp G, Elzaiat Y. Measurement of intraocular distances by backscattering spectral interferometry. Opt Commun. 1995;117:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wojtkowski M, Leitgeb R, Kowalczyk A, Bajraszewski T, Fercher AF. In vivo human retinal imaging by Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt. 2002;7:457–463. doi: 10.1117/1.1482379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cense B, Nassif NA, Chen TC, Pierce MC, Yun SH, Park BH, Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, de Boer JF. Ultrahigh-resolution high-speed retinal imaging using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2004;12:2435–2447. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.002435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wojtkowski M, Srinivasan VJ, Ko TH, Fujimoto JG, Kowalczyk A, Duker JS. Ultrahigh-resolution, high-speed, Fourier domain optical coherence tomography and methods for dispersion compensation. Opt Express. 2004;12:2404–2422. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.002404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wojtkowski M, Srinivasan V, Fujimoto J, Ko T, Schuman J, Kowalczyk A, Duker J. Three-dimensional retinal imaging with high-speed ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1734–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alam S, Zawadzki RJ, Choi SS, Gerth C, Park SS, Morse L, Werner JS. Clinical application of rapid serial Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography for macular imaging. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1425–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drexler W, Fujimoto JG. Optical coherence tomography in ophthalmology. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:041201. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly WJ, III, Roorda A. Optimal pupil size in the human eye for axial resolution. J Opt Soc Am A. 2003;20:2010–2015. doi: 10.1364/josaa.20.002010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang J, Williams DR, Miller DT. Supernormal vision and high-resolution retinal imaging through adaptive optics. J Opt Soc Am A. 1997;14:2884–2892. doi: 10.1364/josaa.14.002884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rha J, Jonnal RS, Thorn KE, Qu J, Zhang Y, Miller DT. Adaptive optics flood-illumination camera for high speed retinal imaging. Opt Express. 2006;14:4552–4569. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi SS, Doble N, Hardy JL, Jones SM, Keltner JL, Olivier SS, Werner JS. In vivo imaging of the photoreceptor mosaic in retinal dystrophies and correlations with visual function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2080–2092. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roorda A, Romero-Borja F, Donnelly WJ, III, Queener H, Hebert TJ, Campbell MCW. Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Opt Express. 2002;10:405–412. doi: 10.1364/oe.10.000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burns SA, Tumbar R, Elsner AE, Ferguson D, Hammer DX. Large-field-of-view, modular, stabilized, adaptive-optics-based scanning laser ophthalmoscope. J Opt Soc Am A. 2007;24:1313–1326. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray DC, Merigan W, Wolfing JI, Gee BP, Porter J, Dubra A, Twietmeyer TH, Ahamd K, Tumbar R, Reinholz F, Williams DR. In vivo fluorescence imaging of primate retinal ganglion cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Opt Express. 2006;14:7144–7158. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.007144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller DT, Qu J, Jonnal RS, Thorn K. Coherence gating and adaptive optics in the eye. Proc SPIE. 2003;4956:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermann B, Fernandez EJ, Unterhubner A, Sattmann H, Fercher AF, Drexler W, Prieto PM, Artal P. Adaptive-optics ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 2004;29:2142–2144. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.002142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merino D, Dainty C, Bradu A, Podoleanu AG. Adaptive optics enhanced simultaneous en-face optical coherence tomography and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Opt Express. 2006;14:3345–3353. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.003345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Rha J, Jonnal RS, Miller DT. Adaptive optics parallel spectral domain optical coherence tomography for imaging the living retina. Opt Express. 2005;13:4792–4811. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.004792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zawadzki RJ, Jones SM, Olivier SS, Zhao M, Bower BA, Izatt JA, Choi S, Laut S, Werner JS. Adaptive-optics optical coherence tomography for high-resolution and high-speed 3D retinal in vivo imaging. Opt Express. 2005;13:8532–8546. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.008532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Cense B, Rha J, Jonnal RS, Gao W, Zawadzki RJ, Werner JS, Jones S, Olivier S, Miller DT. High-speed volumetric imaging of cone photoreceptors with adaptive optics spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2006;14:4380–4394. doi: 10.1364/OE.14.004380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández E, Povazay B, Hermann B, Unterhuber A, Sattman H, Prieto P, Leitgeb R, Anhelt P, Artal P, Drexler W. Three-dimensional adaptive optics ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography using liquid crystal spatial light modulator. Vision Res. 2005;45:3432–3444. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zawadzki RJ, Choi SS, Jones SM, Olivier SS, Werner JS. Adaptive optics–optical coherence tomography: optimizing visualization of microscopic retinal structures in three dimensions. J Opt Soc Am A. 2007;24:1373–1383. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bigelow CE, Iftimia NV, Ferguson RD, Ustun TE, Bloom B, Hammer DX. Compact multimodal adaptive-optics spectral-domain optical coherence tomography instrument for retinal imaging. J Opt Soc Am A. 2007;24:1327–1336. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pircher M, Zawadzki RJ, Evans JW, Werner JS, Hitzenberger CK. Simultaneous imaging of human cone mosaic with adaptive optics enhanced scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and high- speed transversal scanning optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 2008;33:22–24. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pircher M, Zawadzki RJ. Combining adaptive optics with optical coherence tomography: Unveiling the cellular structure of the human retina in vivo. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;2:1019–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zawadzki RJ, Cense B, Zhang Y, Choi SS, Miller DT, Werner JS. Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography with monochromatic and chromatic aberration correction. Opt Express. 2008;16:8126–8143. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.008126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández EJ, Hermann B, Považay B, Unterhuber A, Sattmann H, Hofer B, Ahnelt PK, Drexler W. Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography and pancorrection for cellular imaging of the living human retina. Opt Express. 2008;16:11083–11094. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.011083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferguson RD, Hammer DX, Paunescu LA, Beaton S, Schuman JS. Tracking optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 2004;29:2139–2141. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.002139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arathorn DW, Yang Q, Vogel CR, Zhang Y, Tiruveedhula P, Roorda A. Retinally stabilized cone-targeted stimulus delivery. Opt Express. 2007;15:13731–13744. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.013731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogel CR, Arathorn DW, Roorda A, Parker A. Retinal motion estimation in adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Opt Express. 2006;14:487–497. doi: 10.1364/opex.14.000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi SS, Zawadzki RJ, Keltner JL, Werner JS. Changes in cellular structures revealed by ultrahigh-resolution retinal imaging in optic neuropathies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2103–2119. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zawadzki RJ, Fuller AR, Wiley DF, Hamann B, Choi SS, Werner JS. Adaptation of a support vector machine algorithm for segmentation and visualization of retinal structures in volumetric optical coherence tomography data sets. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:041206. doi: 10.1117/1.2772658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernández E, Drexler W. Influence of ocular chromatic aberration and pupil size on transverse resolution in ophthalmic adaptive optics optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2005;13:8184–8197. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.008184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]