Abstract

PURPOSE

This study was undertaken to improve understanding of the defective lens developmental changes induced by the transgenic overexpression of the Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor RhoGDIα. The study was focused on a single differentially expressed gene encoding ponsin, a cell adhesion interacting signaling adaptor protein.

METHODS

Total RNA extracted from the P7 lenses of Rho GDIα transgenic mice was subjected to cDNA microarray analysis. Ponsin distribution in the mouse lenses was determined by immunofluorescence and immunoblot analyses. Interactions among ponsin, actin, and Rho GTPase signaling pathways were explored in lens epithelial cells.

RESULTS

The RhoGDIα transgenic mouse lenses revealed a marked downregulation of expression of multiple splice variants of ponsin. Expression of one of the ponsins (U58883) was found to be abundant in normal mouse lenses. Although ponsin was localized predominantly to the focal adhesions in lens epithelial cells, it was distributed to both the epithelium and fibers, with some isoforms being enriched primarily in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction in lens tissue. Further, whereas constitutively active RhoA induced ponsin clustering at the leading edges, inhibition of Rho kinase and latrunculin treatment were noted to lead to decreases in ponsin protein levels in lens epithelial cells.

CONCLUSIONS

Abundant expression of ponsin, a focal adhesion protein in the lens tissue indicates a potential role for this protein in lens fiber cell migration and adhesion. Ponsin expression appears to be closely dependent on Rho GTPase–regulated integrity of actin cytoskeletal organization.

The vertebrate lens is a transparent tissue whose anterior surface is covered by a monolayer of epithelial cells, with the rest of the lens being composed of fiber cells that are derived from the differentiation of the epithelial cells at the equatorial region. Lens fiber cell morphology, cytoskeletal organization, migration, membrane remodeling, and intercellular adhesions are some of the key determinants of lens shape, polarity, distinct architecture, and ultimately optical properties. 1–9 Dynamic regulation of actin cytoskeletal organization and cell adhesive interactions plays a pivotal role in various cellular processes,10–12 and perturbation in cytoskeletal organization can compromise lens transparency and induce cataract formation.5,13–15 Since cytoskeletal proteins provide not only structural integrity to most tissues, but also play a crucial role in intracellular signal transduction and regulation of myriad cellular processes,11,12 identifying the regulatory mechanisms involved in cytoskeletal reorganization and cell adhesive interactions in the lens tissue is critical for understanding lens differentiation, polarity, growth, and function.

Various cytoskeletal signaling proteins have been shown to regulate lens growth and maintenance of lens transparency. Recent studies have implicated the involvement of Rho GTPases, Src-kinase, focal adhesion kinase, Wnt, abl-kinase inter-actor proteins, integrins, Cdk-5, PDZ domain protein, and protein kinase C in regulation of lens cytoskeletal organization and cell adhesions, and impaired activity of some of these signaling molecules has been demonstrated to affect lens development and function.5,15–23 Growth factors that regulate lens development and differentiation have been shown to stimulate Rho GTPase activation, actin cytoskeletal reorganization, and formation of cell adhesions in lens epithelial cells.24 Moreover, inactivation of Rho GTPase activity and disruption of actomyosin interaction has been shown to cause deleterious effects on lens growth and function.15,25,26 Although the cellular cytoskeleton constitutes one of the primary targets of the Rho GTPases, these signaling proteins also influence several other cellular processes in a cytoskeleton-dependent or -independent manner. For example, Rho GTPase regulates gene expression and cell cycle progression by controlling the transcriptional activity of serum response factor and NF-KB and activities of ERK, p38, and JNK kinases.27 Impaired activity of Rho GTPases causes microphthalmic eyes in mice.15,25

Therefore, to better understand the broader role of Rho GTPases in lens growth and function, we initially evaluated their influence on the lens gene expression profile. For this, we used lenses derived from the RhoGDIα overexpressing transgenic mice. RNA extracted from these lenses was subjected to cDNA microarray analysis. In this study, we focused on a single differentially expressed gene that showed a marked and consistent downregulation in this mouse model, and encoded ponsin, a cell adhesion interacting signaling adaptor protein.28 Ponsin has also been identified as a c-cbl-associated protein (CAP). c-cbl, a well-characterized proto-oncogene with multiple activities binds to CAP/ponsin, and this binding event has been shown to influence insulin-induced Glut4 (glucose transporter) membrane translocation, ubiquitination, c-abl degradation, and growth factor signaling.29–32 Of importance, CAP/ponsin which belongs to the vinexin family (ponsin/ArgBP2/vinexin) of adaptor proteins, contains three tandem Srchomology (SH3) domains at the C-terminal and a sorbin domain at the N-terminal, and has been shown to interact with a variety of signaling molecules to regulate cell adhesion, cytoskeletal reorganization, membrane trafficking, and signaling.30,33,34

In addition, in this study we determined ponsin distribution in lens tissue and in lens epithelial cells because expression of ponsin was not only downregulated markedly in the Rho GTPase–targeted lenses, but one of the ponsin isoforms was also found to be abundantly expressed in the normal mouse lens. Further, we examined the interrelationship between the expression of ponsin and Rho GTPase–regulated actin cytoskeletal integrity. To our knowledge this is the first report on lens ponsin, its high level of expression in the lens, localization to the focal adhesions, and marked downregulation in Rho GTPase– targeted lenses. Taken collectively, these data indicate a potential essential role for ponsin in lens fiber cell migration, adhesive interactions, and polarity and in maintenance of lens transparency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

In this study, we used a well-characterized transgenic mouse model originally developed and characterized in our laboratory. The transgenic mice overexpress the Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor, RhoGDIα, in a lens-specific manner under the control of a δ1-enhancer/αA-crystallin (δenh/αA) fusion promoter used to drive expression of a bovine RhoGDIα transgene in lens epithelium and fibers.25 The background of this mouse strain was C57/BL6. PCR-based genotyping was performed with tail DNA, to select the Rho GDIα transgenic mice. Both male and female mice (1 week old) were used. Albino FVB strain transgenic mice expressing the Rho GTPase inactivator C3 exoenzyme in a lens-specific manner and generated previously in our laboratory15 were also used. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research in an approved Duke University institutional animal protocol.

cDNA Microarray Analysis

P7 lenses were collected from the Rho GDI transgenic and wild-type mice and stored individually in RNA preservative (RNAlater; Ambion, Austin TX), until further processing. Enough tissue was collected to enable the extraction of at least 1 to 2 µg of total RNA from the pooled RhoGDI transgenic (Tg) and wild-type (WT) littermate lenses. After genotyping, WT and Tg lenses were pooled and total RNA extracted (RNeasy Micro Kit; Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). The quality and concentration of RNA were determined (Nanodrop chip and Bioanalyzer; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). One microgram of total RNA was amplified and gene-expression data were obtained. All steps involved in RNA processing, probe preparation, microarray hybridization, and data processing were based on MIAME (Minimal Information about a Microarray Experiment), the guidelines established by the Microarray Gene Expression Data Society, and the analysis were performed at the Duke University Genome Analysis Core facility. Spotted Oligonucleotide arrays were printed at the Duke Microarray Facility (Operon Mouse Genome Oligo Set ver. 4.0; Operon, Huntsville, AL), which includes 31,834 gene transcripts (optimized 70mers). A commercial software program (GeneSpring GX, ver. 7.3; Agilent Technologies) was used to perform data analysis. Based on duplicate analyses of each condition, the threshold of a twofold change in expression relative to control was considered significant.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR and RT-PCR

Real-time quantification of ponsin mRNA splice variants in WT and RhoGDI Tg lenses was performed with a detection system (iCycler iQ; Bio-Rad, Philadelphia, PA), as described earlier by us.35

To determine the expression profile of ponsin isoforms in mouse lens tissue, we performed RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction) analysis of total RNA extracted from the mouse lenses. The following four mouse-specific ponsin primer sets were used in RT-PCR reactions:

CAP/ponsin (GenBank accession no. AF078666; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank; provided in the public domain by National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD): 5′-GAT CCT GCC TCA GAG AGA AGA GCG-3′ and 5′-GGG CTG GAC TTG AGT GAG GAA GAG-3′;CAP/ponsin (accession no. U58883): 5′-TAA AGC TGT GGT GAA TGG CTT GGC-3′ and 5′-ACA CTT CTA TAG CCC TTG GCA GCA-3′; CAP/ponsin (coiled coiled domain): 5′-TGG GCT CAA GCG ACT TTC-3′ and 5′-CAG TTC TGG TCA ATC TGT CTG TAG-3′; CAP/ponsin (proline-rich region): 5′-CCG TCT GAG GTA ATA GTT GTT CC-3′ and 5′-GAG CAC AAT GGT AGG GTT GAC G-3′.

Where necessary, minus RT controls were included in RT-PCR analysis. The PCR products were sequenced to confirm identity of mouse ponsin isoforms.

Cell Culture

Mouse lens epithelial cells were isolated from the lens capsules derived from 1-month-old C57/B6 strain animals by collagenase IV digestion, as described earlier by us.36 Third- and fourth-passage cells were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin (100 U/mL)-streptomycin (100 µg/mL)-glutamine (292 µg/mL). Cells cultured in 1% serum were treated with Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (20 µM) and latrunculin B (100 nM) for 24 hours to determine their effects on ponsin expression. Third- and fourth-passage cells were used in the study.

Transfections

Plasmids expressing the GFP tagged-CAP/ponsin or GFP alone (sub-cloned CAP cDNA into eGFP-C1 vector; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were provided by Alan Saltiel (Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). These plasmids were isolated and purified in a standard protocol with a plasmid-isolation kit (Qiagen). Mouse lens epithelial cells (1 × 105) were transfected by electroporation (Nucleofector device and nucleofection reagents; Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Electroporated cells were cultured on gelatin-coated glass coverslips.

Well-characterized replication-defective recombinant adenoviral vectors (Adtrack-CMV vectors) encoding either enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) alone or GFP and constitutively active mutant RhoAV14 (Gly14→Val) were provided by Patrick J. Casey (Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University School of Medicine). Viral vectors were amplified by using HEK293 cells and were purified (Adeno-X Virus purification kit; BD Biosciences), as we describe elsewhere.35 Primary mouse lens epithelial cells cultured to 80% confluence either on gelatin-coated glass coverslips or in plastic Petri plates were infected with adenoviral vectors expressing either GFP alone or RhoAV14 and GFP at 30 MOI (multiplicity of infection). The expression of GFP was evaluated by recording the green fluorescence with a phase-contrast microscope (model AX10; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA) equipped with a fluorescent light source.

Immunofluorescence

Lens epithelial cells grown on gelatin-coated glass coverslips were fixed for immunofluorescence analysis of ponsin distribution, actin cytoskeletal organization, and focal adhesions, as described previously. 36 Actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), whereas focal adhesions and ponsin were stained with primary antibodies raised against vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich) and ponsin (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) respectively, in conjunction with the use of Alexa Flour 488– or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies-Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Representative micrographs were recorded by confocal microscope (Eclipse 90i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Lens epithelial cells treated with Y-27632 (20 µM) and latrunculin B (100 nM) for 2 hours were immunostained for ponsin, as described earlier.

Cryostat sections derived from neonatal mouse lenses (7 µm, sagittal planes) were air dried and immunostained with polyclonal antibody raised against ponsin in conjunction with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Life Technologies-Molecular Probes) as described earlier, and viewed by confocal microscope.15

Immunoblot Analysis

Lens epithelial and fiber cell total, soluble, Triton-soluble, and Triton-insoluble fractions were prepared as we described earlier37 and subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE. Equal amounts of lens protein (40 µg) were separated on 10% acrylamide gels, followed by electrophoretic transfer to nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked with 3% milk protein and then incubated with ponsin polyclonal antibody against the intact human protein sequence (Upstate Biotechnology). Immunoblots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). Similarly, lens-soluble and -insoluble fractions derived from the Rho GDI and C3-exoenzyme transgenic mice were examined for changes in ponsin protein levels by immunoblot analysis.

Cell pellets obtained from RhoAV14-transfected or Y-27632 or latrunculin B-treated lens epithelial cells were suspended in cell lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10 mM PMSF, 0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 25 µg/mL each of aprotinin and leupeptin, and 1 µM okadaic acid. Cell lysates were briefly sonicated and precleared of nuclear debris (800g for 10 minutes at 4°C), and protein content was measured by using a protein-detection reagent (Bio-Rad). Immunoblot analysis was performed in these lysates as described earlier, to determine the changes in the ponsin protein levels in the RhoAV14-expressing and Y-27632- and latrunculin B-treated cells.

RESULTS

Downregulation of Expression of the Cell Adhesion–Associated Adaptor Protein Ponsin in the Rho GTPase Target Mouse Lenses

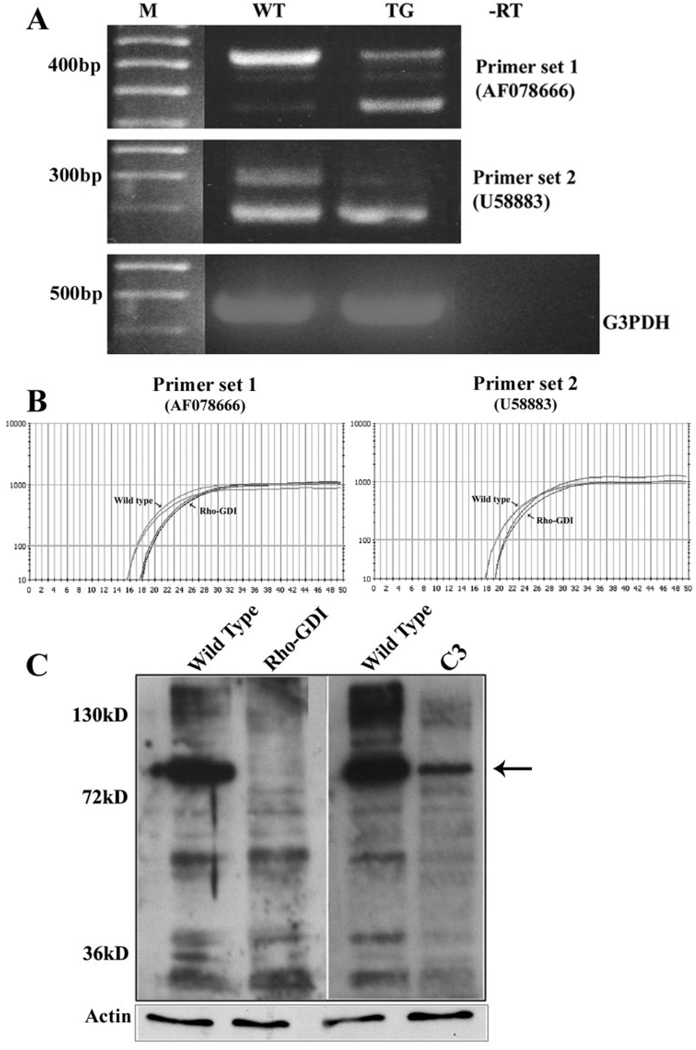

To better understand the morphologic and developmental defects exhibited by the ocular lens in transgenic mice overexpressing the Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor RhoGDIα, we evaluated differential gene expression profiles by cDNA microarray analysis, using spotted arrays containing ≈32,000 individual gene transcripts. Lenses from the RhoGDIα-overexpressing mice (7 days old) revealed a marked and consistent downregulation (2- to 12-fold) of the expression of multiple splice variants of CAP/ponsin, an adaptor protein involved in actin cytoskeletal organization, trafficking, and growth factor signaling (Table 1). Among the four different splice variants that were downregulated, the expression of ponsin-2 (AF078666) was maximally affected in the Rho GDI transgenic mouse lenses. cDNA microarray analysis of two independent RNA samples derived from pooled lenses (8–10 lenses per sample) of the Rho GDI transgenic mice exhibited similar results, as shown in Table 1. The downregulated expression of ponsin splice variants in the Rho GDIα transgenic mouse lenses was further confirmed by semiquantitative and quantitative PCR analyses as shown in Figures 1A and 1B, respectively. Two different ponsin-specific oligonucleotide primer sets were used in the semiquantitative and quantitative PCR analyses, and these primer sets amplified multiple ponsin-specific DNA fragments confirmed by direct sequencing analysis. Whereas expression of some ponsin variants was markedly decreased, others were found to be unaltered or even exhibited a compensatory response (Fig. 1A, bottom band with primer set 1). So far, more than 10 different ponsin splice variants have been documented to be expressed in different tissues.38 We also determined ponsin protein levels in the Rho GDI transgenic lenses and in the Rho GTPase inactivated C3 exoenzyme expressing transgenic lenses (P7; 10 lenses were pooled per sample) by immunoblot analysis. Both the RhoGDI and C3-exoenzyme-expressing transgenic lenses revealed a substantial decrease in different isoforms of ponsin protein in the insoluble fractions, relative to the WT lenses (Fig. 1C). Of interest, in Rho GTPase inactivated lenses, the levels of many of the ponsin isoforms were found to be substantially decreased compared with Rho GDI transgenic lenses, in which the 90-kDa ponsin was the main isoform whose expression was found to be decreased markedly (Fig. 1C).

TABLE 1.

Downregulation of Ponsin in the RhoGDIα-Overexpressing Transgenic Mouse Lenses Compared with Wild-Type Mouse Lenses

| CAP/Ponsin Splice Variants (GenBank No.) |

Sample 1 (x-Fold Decrease) |

Sample 2 (x-Fold Decrease) |

|---|---|---|

| Variant 1 (U58883) | 2.52 | 2.79 |

| Variant 3 (AF078667) ponsin-1 | 2.71 | 2.54 |

| Variant 4 (AF078666) ponsin-2 | 12.1 | 3.36 |

| Variant 5 (AF521593) | 5.18 | 4.57 |

P7 lenses were pooled for these analyses, and results were based on cDNA microarray analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Downregulation of ponsin expression in Rho GTPase–targeted mouse lenses. In addition to cDNA microarray data, the downregulation of ponsin expression in Rho GDIα transgenic mouse lenses was confirmed by semiquantitative (A) and quantitative (B) RT-PCR analyses and by immunoblot analysis (C). Equal amounts of total RNA derived from the P7 lenses (pooled) of Rho GDIα transgenic and littermate wild-type mice were reverse transcribed. Complementary DNA from the RT reaction was subjected to semiquantitative and quantitative PCR analyses with two different ponsin sequence-specific oligonucleotide primer sets. (A) The two different ponsin-specific oligonucleotide primer sets used for PCR analysis amplified more than one splice variant of ponsin, and with both sets of primers, the expression of one of the ponsin variants (top bands) was found to be markedly decreased in Rho GDIα transgenic lenses. Contrarily, one of the ponsin variants (bottom band with first primer sets) was found to be marginally increased in the Rho GDIα transgenic lenses compared with wild-type lenses. Expression of G3PDH was used as an internal control to normalize the cDNA content in the PCR reactions. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of ponsin expression using two different oligonucleotide primer sets revealed an obvious decrease in Rho GDIα transgenic lenses compared with wild-type lenses. The q-PCR traces from duplicate reactions are depicted. (C) Immunoblot analysis of ponsin isoforms in lenses derived from Rho GDIα– and C3 exoenzyme (Rho GTPase inactivating bacterial toxin)– overexpressing transgenic mice. The water-insoluble fraction derived from pooled P7 lenses was subjected to immunoblot analysis with a polyclonal anti-ponsin antibody that reacts with different CAP/ponsin isoforms. In both the Rho GDIα transgenic and C3 exoenzyme– overexpressing transgenic lenses, protein levels of ponsin isoforms were found to be markedly decreased compared with wild-type lenses. Compared with Rho GDIα–transgenic lenses in which the >90-kDa (arrow) immunopositive band was decreased dramatically, several different ponsin immunopositive protein bands were found to be decreased in addition to the 90-kDa isoform in the C3 transgenic lenses. These results were based on duplicates of pooled lenses.

Abundant Expression of Ponsin in Mouse Lens Tissue

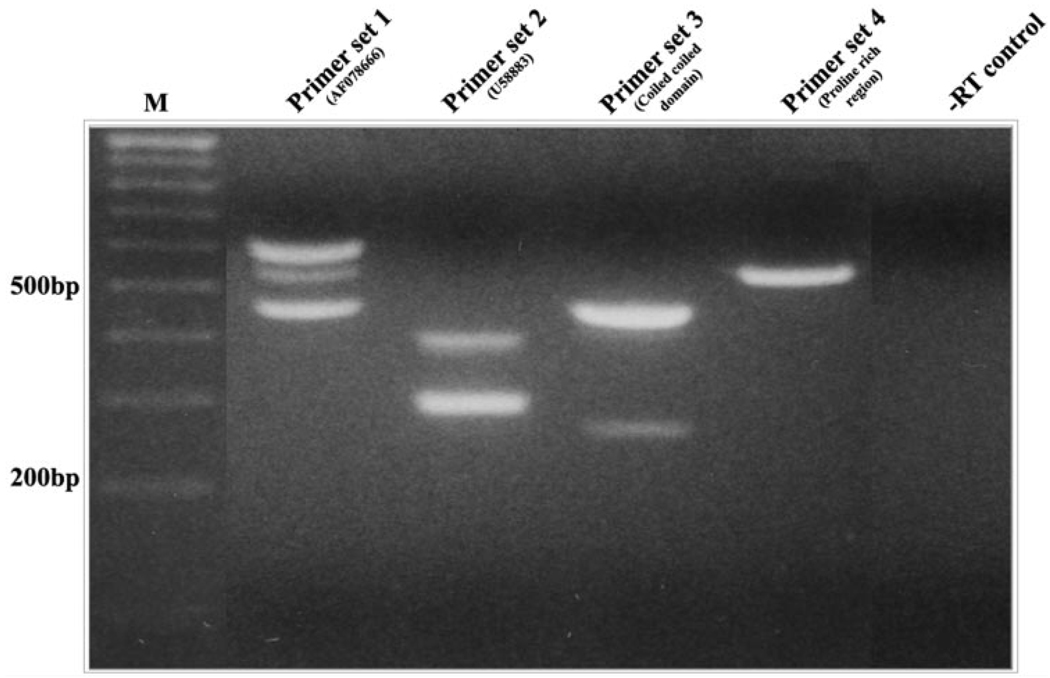

The basal level of expression of one of the splice variants of ponsin (U58883) was found to be relatively abundant in normal mouse lenses, representing one of 60 most highly expressed genes out of a total of ≈26,000 genes that showed a detectable positive expression signal in the cDNA microarray analysis (Table 2 and Table 3). On a relative basis, the copy number of transcripts of the ponsin slice variant U58883 (≈27,000) in the mouse lens was found to be very close to the copy number of transcripts of vimentin (22,700) spectrin (24,444), and MIP26 (28,733) and some of the crystallins (βB1 and βA2) in the same lenses. Although cDNA microarray confirmed expression of five different ponsin splice variants in the P7 mouse lenses (Table 2), RT-PCR analysis of mouse lens RNA (derived from a 1-day-old mouse) using four different ponsin-specific oligonucleotide primer sets derived from the different regions of the coding sequence and with 30 cycles of PCR amplification confirmed expression of multiple splice variants (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Expression Profile of Ponsin Variants in the P7 Mouse Lenses

| CAP/Ponsin Splice Variants (GenBank No.) |

Sample 1 (Raw Expression Level) |

Sample 2 (Raw Expression Level) |

Sample 3 (Raw Expression Level) |

|---|---|---|---|

| U58883 | 25,631 | 26,892 | 27,466 |

| AF078667 | 16,678 | 18,119 | 12,662 |

| AF521593 | 7,228 | 5,115 | 7,760 |

| AF078666 | 2,311 | 2,319 | 2,583 |

| U58889 | 202 | 142 | 168 |

Higher raw expression levels indicate a higher expression of a particular gene relative to the other CAP/ponsin variants reported in the table. These results were derived from cDNA microarray raw data.

TABLE 3.

Relative Abundance of Ponsin Variant Expression Compared with the Total Number of Genes Expressed in the P7 Mouse Lenses

| CAP/Ponsin Variants |

Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| U58883 | 67 | 55 | 57 |

| AF078667 | 160 | 102 | 251 |

| AF521593 | 741 | 1,047 | 587 |

| AF078666 | 2,234 | 2,127 | 1,860 |

| U58889 | 9,147 | 10,699 | 10,075 |

| Least-expressed gene | 26,081 | 26,637 | 28,831 |

The gene that showed highest raw expression value was given a serial number of 1 and from there the increasing serial number indicates the descending order of the expression level of any given gene. For example, the least-expressed gene in the sample 1 was 26,081.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of expression profile of ponsin splice variants in the mouse lens. Four different sequence-specific oligonucleotide primer sets (derived from the different regions of the CAP/ponsin sequence) were used to amplify ponsin-specific DNA fragments by RT-PCR analysis using total RNA derived from 1-day-old mouse lenses. The DNA fragments amplified from 30 PCR cycles are depicted. Sequence specificity was confirmed by direct sequencing.

Distribution of Ponsin in Mouse Lens

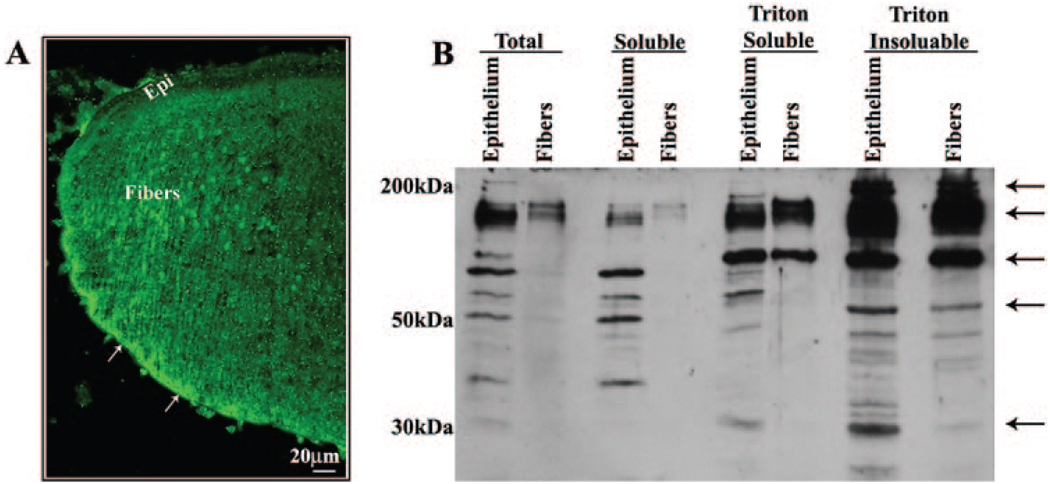

Ponsin was distributed to the epithelium and fibers in the intact mouse lens based on immunofluorescence detection in sagittal cryosections (Fig. 3A). In lens fibers, ponsin distribution was found to be punctate and localized along the lateral membrane with intense staining at the basal ends of the fiber terminals (Fig. 3A, arrows). In isolated lens fractions, different isoforms as well as proteolytically cleaved ponsin (molecular weight ranging between 30 and >150 kDa) were readily detectable in the total and soluble fractions of the lens epithelium. Ponsin-specific immunoreactivity was noted to be much stronger in the lens epithelial total and soluble protein fractions compared to the lens fiber fractions, based on equal protein loading (Fig. 3B). However, in the Triton-soluble and -insoluble fractions of both the lens epithelium and fiber mass, ponsin-specific immunoreactivity was much stronger than the lens-soluble fractions from both epithelium and fibers (Fig. 3B). Further, compared to the Triton-soluble fractions of both epithelium and fibers, an additional and distinct ponsin-specific immunopositive protein band of ≥200 kDa was observed in the Triton-insoluble fractions of the lens epithelium and fiber mass (Fig. 3B). Overall, most lens ponsin appears to be associated with the cytoskeletal fraction of both epithelium and fiber cells (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Determination of spatial and subcellular distribution of ponsin in the mouse lens. (A) The distribution of ponsin in the lens epithelium and fiber cells was determined by labeling cryosections derived from 1-day-old mouse lenses with polyclonal ponsin antibody in conjunction with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody, followed by confocal image analysis. Arrows: an intense and somewhat punctate localization of ponsin to the posterior tips of the lens fibers and along the lateral membrane of the fiber cells. (B) The distribution profile of ponsin protein in different fractions of the lens was determined by subjecting epithelial and fiber cell protein fractions (40 µg/lane) derived from the adult mouse lens (total, soluble, and Triton-soluble and -insoluble fractions) to immunoblot analysis with polyclonal ponsin antibody. Multiple immunopositive ponsin-specific protein bands ranging in size from 30 to >150 kDa were identified in different fractions of the lens epithelium and fiber mass.

Cellular Distribution of Ponsin in the Mouse Lens Epithelial Cells

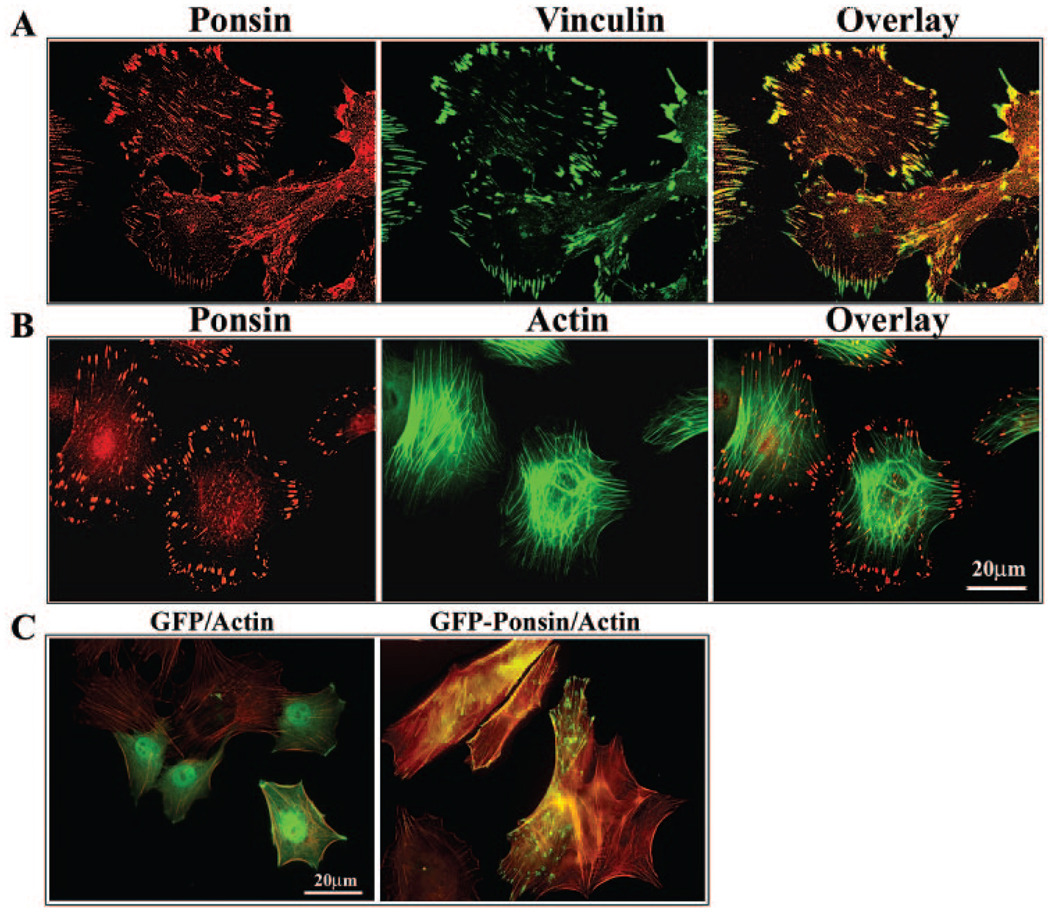

Ponsin displayed an intense and specific focal distribution at the cell peripheral or leading edges in cultured primary mouse lens epithelial cells (Fig. 4A). Ponsin immunostaining colocalized with vinculin, and this colocalization was found to be prominent at the cell peripheral adhesion sites (Fig. 4A). Double-labeling cells for actin filament (phalloidin staining) and ponsin revealed ponsin localization to the tips of the actin stress fibers (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, expression of GFP-tagged recombinant ponsin in mouse lens epithelial cells also confirmed a distinct pattern of distribution for ponsin to the focal adhesions, and of note, induced actin stress fiber formation (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Ponsin localization to the focal adhesions in mouse lens epithelial cells. The cellular distribution of ponsin in lens epithelial cells and ponsin interactions with focal adhesions (A) and the actin cytoskeleton (B) were explored by immunolabeling primary mouse lens epithelial cells for CAP/ponsin, focal adhesions (vinculin staining), and actin filament (FITC-phalloidin staining). Ponsin-, vinculin-, and actin filament–specific staining was recorded individually by confocal microscope, and images were also superimposed to evaluate for colocalization of these three proteins. Ponsin localizes uniquely to the focal adhesions (A) and to the tips of the actin stress fibers (B). (C) The distribution pattern of recombinant ponsin and its effects on cell morphology and actin cytoskeletal organization were determined by transfection of mouse lens primary epithelial cells (by electroporation) with plasmids expressing ponsin-GFP or GFP alone. Serum-starved cells were fixed and examined for changes in actin filament organization and distribution of recombinant ponsin. Recombinant ponsin displayed a focal distribution pattern similar to that of endogenously expressed protein, localizing to the tips of actin stress fibers and to the leading edges of the cell. Further, expression of recombinant ponsin increased actin stress fiber formation compared with GFP-expressing control cells. These results were based on three independent experiments.

Effects of Rho Signaling on Ponsin Distribution

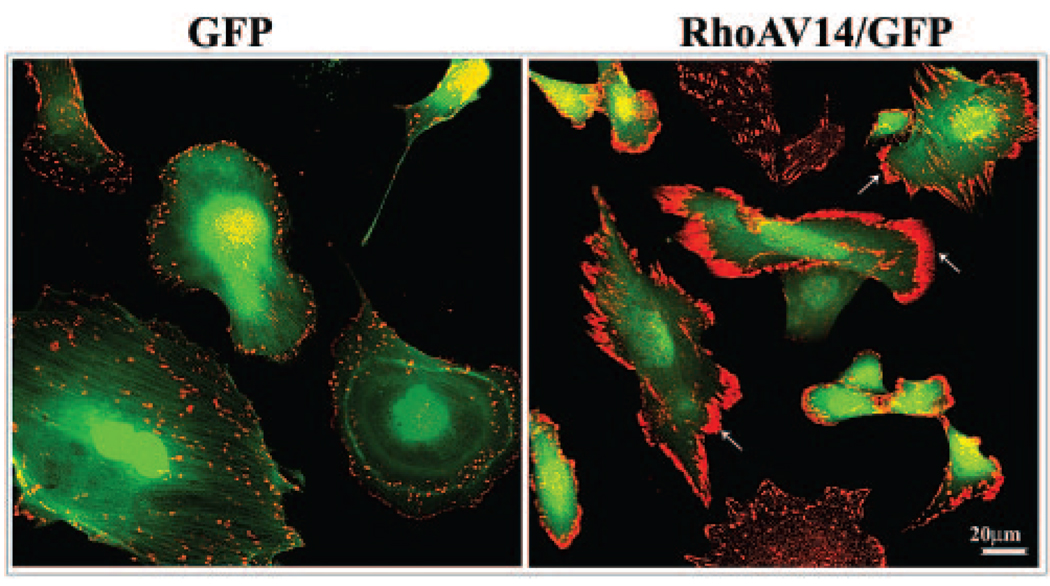

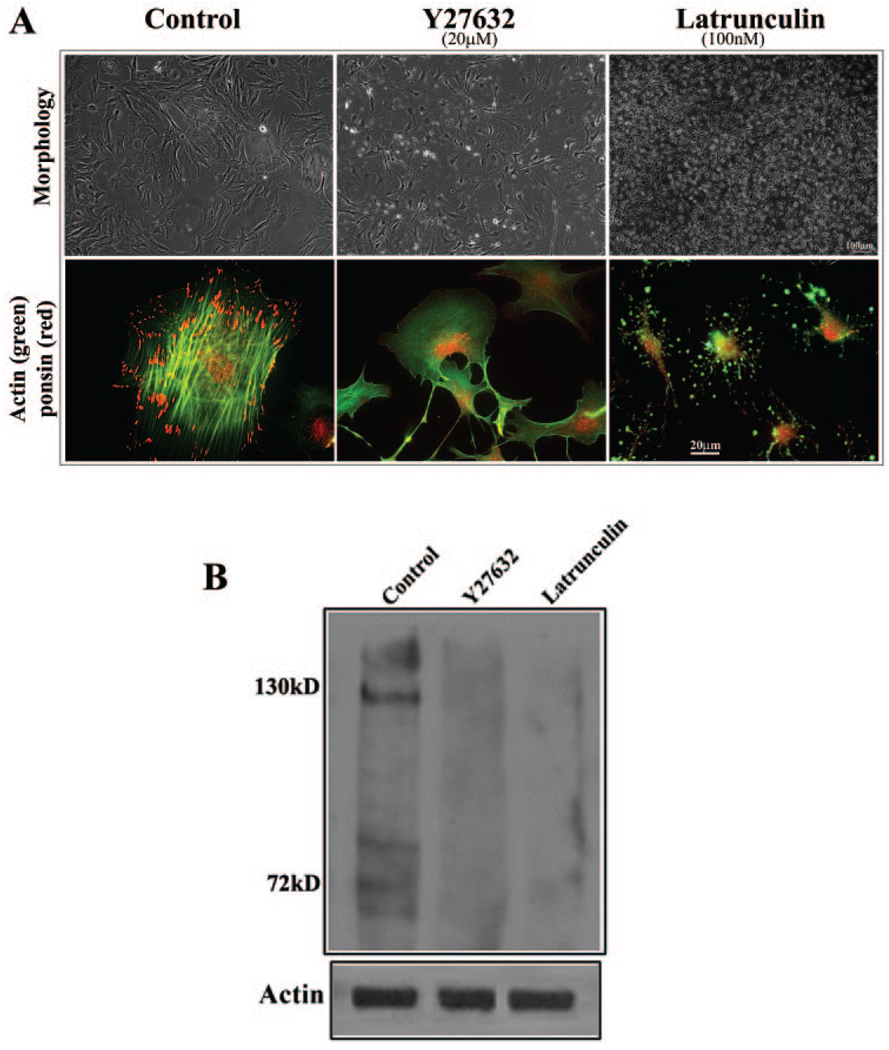

Expression of constitutively active RhoA (RhoAV14 mutant) in mouse lens epithelial cells in the serum-free condition led to distinct redistribution and clustering of ponsin at the leading edges (Fig. 5). This effect of RhoA on ponsin redistribution was not found to be associated with any substantial increase in the ponsin protein levels as tested by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). Conversely, inhibition of Rho kinase (Y-27632, 20 µM for 2 hours) and actin depolymerization induced by latrunculin B (100 nM for 2 hours) in mouse lens epithelial cells completely diminished ponsin localization to the focal adhesions (Fig. 6) indicating the influence of Rho/Rho kinase signaling and integrity of actin cytoskeletal organization on ponsin interaction with focal adhesions.

FIGURE 5.

Influence of Rho GTPase activity on the cellular distribution of ponsin in lens epithelial cells. The potential involvement of Rho GTPase function in the cellular distribution of ponsin was examined by transfecting primary mouse lens epithelial cells with constitutively active Rho GTPase (RhoAV14) along with GFP. RhoAV14 expression caused a dramatic clustering and reorganization of ponsin (arrows: red immunofluorescence) to the leading edges of cells under conditions of serum starvation. In contrast, GFP expression (green fluorescence) did not cause any noticeable effects relative to nontransfected control cells (not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Influence of actin polymerization on the distribution and expression of ponsin in lens epithelial cells. The potential relationship between actin filament organization and ponsin distribution and expression was explored by treating mouse lens primary epithelial cells with the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (20 µM) or latrunculin B (100 nM) and examining them for changes in ponsin distribution and levels. (A) Lens epithelial cells treated with Y-27632 and latrunculin B for 2 hours exhibited cell– cell separation and detachment and changes in cell morphology. As expected, the cells exhibited an almost complete loss of actin stress fibers (FITC fluorescence). But intriguingly, the loss of actin stress fibers was associated with a striking decrease in ponsin (red fluorescence) localization to the focal adhesions. (B) Since actin depolymerization appears to lead to a decrease in ponsin levels, ponsin levels were also evaluated by immunoblot analysis of Rho kinase inhibitor– and latrunculin B–treated (24 hours) cells. Membrane-rich insoluble fractions derived from these cells revealed a substantial reduction in ponsin protein level compared with untreated control cells. These data are representative of two independent experiments.

Influence of Actin Cytoskeletal Integrity on Ponsin Expression

To obtain further insight into the downregulation of ponsin expression in the Rho GTPase–targeted (both Rho GDI and C3 exoenzyme–expressing) transgenic mice, we determined ponsin protein levels in lens epithelial cells treated either with Rho kinase inhibitor (Y-27632) or with latrunculin B, an actin-depolymerizing agent. As expected, lens epithelial cells treated with both the Rho kinase inhibitor (20 µM Y-27632 for 24 hours) and latrunculin B (100 nM for 24 hours) showed a dramatic change in cell morphology exhibiting cell– cell detachment and a rounded or filamentous cell shape (Fig. 6A). Actin filaments stained with rhodamine-phalloidin showed a marked decrease in actin stress fibers (Fig. 6A). Cells treated with Y-27632 and latrunculin for 24 hours were lysed and extracted, and the soluble and insoluble fractions examined for changes in ponsin protein levels by immunoblot analysis. Ponsin protein levels were found to be dramatically reduced especially in the insoluble fraction derived from both Y-27632 and latrunculin-treated lens epithelial cells (Fig. 6B), indicating the existence of a potentially close association between actin cytoskeletal integrity and regulation of ponsin expression.

DISCUSSION

Rho GTPases play a critical role(s) in various cellular processes in addition to their well-recognized involvement in actin dynamics, cell adhesion, and cell migration.11,12,27 Based on an observed unique phenotype in mouse lenses overexpressing the negative regulator of Rho GTPase, Rho GDIα, it is evident that these molecules play a vital role(s) in lens epithelial cell migration, differentiation, and cytoskeletal organization.25 To seek further insight into the molecular basis for the lens phenotype in these mouse lenses, we evaluated the differential gene expression profile by cDNA microarray analysis. In this study, we report that the expression of multiple splice variants of CAP/ponsin, a cytoskeletal interacting and signaling adaptor protein, was consistently and markedly downregulated in the Rho GTPase–targeted lenses. Moreover, ponsin expression and distribution appeared to be closely regulated by the Rho/Rho kinase–mediated actin cytoskeletal organization in lens epithelial cells. Further, expression of one of the splice variants of CAP/ponsin in normal lens was found to be very abundant and was distributed to the fiber cell basal ends and cell– cell junctions. Collectively, these observations indicate potentially a vital role for ponsin in lens cytoskeletal organization, fiber cell migration and adhesive interactions.

Lens fiber cell polarity, migration and cell– cell interactions have a fundamental role in lens differentiation, growth, and maintenance of function.5,39 Therefore, understanding the signaling mechanisms regulating cytoskeletal organization and cell adhesions in the lens is critical. Having found serendipitously that the expression of ponsin is markedly downregulated in the Rho GTPase–targeted lenses, we were keenly interested in exploring a possible role for this protein in lens growth and function, since ponsin is known to regulate various cellular processes such as cytoskeletal organization, cell adhesions, and cell spreading, trafficking, and signaling.28,30,31,33,34 Ponsin was originally identified as afadin and vinculin-binding cell adhesion protein, and the same protein was later identified as CAP involved in insulin signaling and Glut4 membrane translocation.28–32 CAP/ponsin belongs to the SoHo family of adaptor proteins which include ponsin, vinexin, and ArgBP2, expressed ubiquitously.30 Each of these proteins contains an N-terminal sorbin homology (SoHo) domain and three C-terminal SH3 domains that bind to diverse signaling molecules involved in a variety of cellular processes.30,33,40 P7 mouse lenses were found to express five different splice variants of CAP/ponsin with expression profiles displaying a 150-fold difference between the less (U58889) and highly (U58883) abundant variants based on the cDNA microarray raw data. Variant 1 (U58883) was found to be one of the 60 most abundantly expressed proteins in the mouse lens, with this group of genes also including the various crystallins, which are the most abundant proteins of the lens. Ponsin-2 (AF078666), whose expression appears to be 10 times lower than that of variant 1, was maximally downregulated in the Rho GTPases targeted lenses. So far more than 10 different splice variants of CAP/ponsin have been documented to be present in different cell types, however, it is not clear whether these multiple variants play either any unique role(s) or exhibit tissue specific distribution. It has been reported that different ponsin variants exhibit distinct binding affinity to the focal adhesions.30,38

Of interest, the gene Sh3d5 (AA797294), which was later identified as CAP/ponsin, has been reported to exhibit unique developmental regulation in the mouse lens compared to the other ocular tissues including cornea, iris, and ciliary body, indicating a critical role for this protein in lens development and growth.41 In addition, in humans, CAP/ponsin is localized to chromosome 10, region q23.3-q24.1,42 and this same locus has been mapped to bilateral posterior polar cataract. PITX3, a homeobox transcription factor, which is also localized to this region, has been shown to carry a mutation in patients with hereditary posterior polar cataract.43 However, whether altered CAP/ponsin activity also contributes to the posterior polar cataract in some of the patients is a provocative possibility, 44 since the expression of CAP/ponsin appears to be abundant in the lens tissue. Mutations in the lens-abundant proteins including crystallins, aquaporins, and connexins are commonly associated with various genetic cataracts.45

CAP/ponsin and its related proteins vinexin and ArgBP2 have been shown to influence cell migration, cell spreading, focal adhesion formation, and actin cytoskeletal organization. 28,30,46,47 Further, ponsin interacts with c-cbl ubiquitin ligase, regulates growth factor signaling, and also regulates ERK and PAK kinase activities.31,33,48 Ponsin has been shown to accumulate in lipid rafts and interact with flotillin.34 Therefore, to explore the role of ponsin in lens epithelial cell elongation and cytoskeletal organization, we induced overexpression of GFP-fused ponsin. Overexpression of recombinant ponsin confirmed its specific localization to the focal adhesions and induced formation of actin stress fibers but did not influence cell morphology in any unique fashion. A similar effect has been reported in CAP overexpressing fibroblasts where ponsin has been demonstrated to influence cell spreading by regulating ERK kinase activity.33 On the other hand, overexpression of constitutively active Rho GTPase (RhoAV14) in lens epithelial cells increased ponsin-associated focal adhesions and ponsin clustering at the leading edges of migrating cells, suggesting a role for Rho signaling in ponsin-induced cellular response, with ponsin likely acting downstream of Rho signaling. Although the role of Rho GTPase in regulation of actin stress fiber and focal adhesions formation has been extensively studied, the downstream effectors of Rho GTPase are not yet fully characterized. 11,27 Furthermore, an inhibitor of Rho kinase dramatically reduced ponsin-associated focal adhesions in the lens epithelial cells, strengthening the case for a potential functional interrelationship between Rho GTPase activity and ponsin.

To obtain further insight into why ponsin expression is downregulated in response to impairment of Rho GTPase activity and also to evaluate whether this response was due to altered actin cytoskeletal integrity and cell adhesive interactions, we determined the effects of Rho kinase inhibitor and actin depolymerizing agent, latrunculin on ponsin protein levels in the lens epithelial cells. Ponsin protein levels were markedly diminished in association with decreased actin stress fibers and focal adhesions in lens epithelial cells treated with both Rho kinase inhibitor and latrunculin, indicating the existence of a potential association between the integrity of actin cytoskeleton/cell adhesive interaction and the expression of ponsin. This conclusion was further supported by the decreased levels of ponsin in RhoA inactivated C3 exoenzyme expressing transgenic mouse lenses as well (Fig. 1C). The Rho GTPase–targeted lenses exhibit abnormal lens fiber cell migration and disrupted actin cytoskeletal organization.15,25 Moreover, CAP/ponsin has been suggested to regulate muscle structural integrity by interacting with filamin C.49 Another interesting feature of the SoHo family of proteins, especially in the case of ArgBP2, is that they are thought to regulate the contractile and elastic activity of sarcomeres.47 Although accommodation is a critical property of the ocular lens, the contractile properties of lens tissue are poorly understood. One of our recent studies revealed a robust increase in myosin II phosphorylation in differentiating lens fibers and indicated a significance for this event in maintaining lens transparency.26 Furthermore, ponsin has been shown to be localized to the cell– cell adherens junctions in the different cell types.28 Since lens fiber cell cortical adherens have been reported to contain both vinculin and N-cadherin,8 it is likely that ponsin, by interacting with these proteins, regulates lens fiber cell cortical adhesive interactions and potentially participates in lens fiber cell packing and architecture. Therefore, further studies are critical for a thorough understanding of the role(s) of CAP/ponsin and related adaptor proteins in lens growth, development, and function.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ann Marie Pendergast for valuable critiques of the manuscript and Joe Christenbury, Nomi Tserentsoodol, and Ying Hao for technical help.

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute Grants EY12201 and EY018590 (PVR).

Footnotes

Disclosure: P.V. Rao, None; R. Maddala, None

References

- 1.Taylor VL, al-Ghoul KJ, Lane CW, Davis VA, Kuszak JR, Costello MJ. Morphology of the normal human lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1396–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassnett S, Missey H, Vucemilo I. Molecular architecture of the lens fiber cell basal membrane complex. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2155–2165. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menko S, Philp N, Veneziale B, Walker J. Integrins and development: how might these receptors regulate differentiation of the lens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;842:36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piatigorsky J. Lens differentiation in vertebrates: a review of cellular and molecular features. Differentiation. 1981;19:134–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1981.tb01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao PV, Maddala R. The role of the lens actin cytoskeleton in fiber cell elongation and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Ghoul KJ, Kuszak JR, Lu JY, Owens MJ. Morphology and organization of posterior fiber ends during migration. Mol Vis. 2003;9:119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee A, Fischer RS, Fowler VM. Stabilization and remodeling of the membrane skeleton during lens fiber cell differentiation and maturation. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:257–270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200003)217:3<257::AID-DVDY4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straub BK, Boda J, Kuhn C, et al. A novel cell-cell junction system: the cortex adhaerens mosaic of lens fiber cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4985–4995. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beebe DC, Vasiliev O, Guo J, Shui YB, Bassnett S. Changes in adhesion complexes define stages in the differentiation of lens fiber cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:727–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burridge K, Wennerberg K. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell. 2004;116:167–179. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mousa GY, Trevithick JR. Differentiation of rat lens epithelial cells in tissue culture. II. Effects of cytochalasins B and D on actin organization and differentiation. Dev Biol. 1977;60:14–25. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beebe DC, Cerrelli S. Cytochalasin prevents cell elongation and increases potassium efflux from embryonic lens epithelial cells: implications for the mechanism of lens fiber cell elongation. Lens Eye Toxic Res. 1989;6:589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maddala R, Deng PF, Costello JM, Wawrousek EF, Zigler JS, Rao VP. Impaired cytoskeletal organization and membrane integrity in lens fibers of a Rho GTPase functional knockout transgenic mouse. Lab Invest. 2004;84:679–692. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker J, Menko AS. Integrins in lens development and disease. Exp Eye Res. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.020. Published online July 11, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sue Menko A. Lens epithelial cell differentiation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:485–490. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Stump RJ, Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW. A role for Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling during lens fiber cell differentiation? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kokkinos MI, Brown HJ, de Iongh RU. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) expression and activation during lens development. Mol Vis. 2007;13:418–430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Negash S, Wang HS, Gao C, Ledee D, Zelenka P. Cdk5 regulates cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion in lens epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2109–2117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.10.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grove M, Demyanenko G, Echarri A, et al. ABI2-deficient mice exhibit defective cell migration, aberrant dendritic spine morphogenesis, and deficits in learning and memory. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10905–10922. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10905-10922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen MM, Nguyen ML, Caruana G, Bernstein A, Lambert PF, Griep AE. Requirement of PDZ-containing proteins for cell cycle regulation and differentiation in the mouse lens epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8970–8981. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.8970-8981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker JL, Zhang L, Menko AS. Transition between proliferation and differentiation for lens epithelial cells is regulated by Src family kinases. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:361–372. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maddala R, Reddy VN, Epstein DL, Rao V. Growth factor induced activation of Rho and Rac GTPases and actin cytoskeletal reorganization in human lens epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 2003;9:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maddala R, Reneker LW, Pendurthi B, Rao PV. Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor-mediated disruption of Rho GTPase activity impairs lens fiber cell migration, elongation and survival. Dev Biol. 2008;315:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maddala R, Skiba N, Vasantha Rao P. Lens fiber cell elongation and differentiation is associated with a robust increase in myosin light chain phosphorylation in the developing mouse. Differentiation. 2007;75:713–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the control of cell behaviour. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:891–895. doi: 10.1042/BST20050891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandai K, Nakanishi H, Satoh A, et al. Ponsin/SH3P12: an l-afadinand vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1001–1017. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang SH, Baumann CA, Kanzaki M, et al. Insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation requires the CAP-dependent activation of TC10. Nature. 2001;410:944–948. doi: 10.1038/35073608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kioka N, Ueda K, Amachi T. Vinexin, CAP/ponsin, ArgBP2: a novel adaptor protein family regulating cytoskeletal organization and signal transduction. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:1–7. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribon V, Herrera R, Kay BK, Saltiel AR. A role for CAP, a novel, multifunctional Src homology 3 domain-containing protein in formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4073–4080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribon V, Printen JA, Hoffman NG, Kay BK, Saltiel AR. A novel, multifunctional c-Cbl binding protein in insulin receptor signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:872–879. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Liu J, Cheng A, et al. CAP interacts with cytoskeletal proteins and regulates adhesion-mediated ERK activation and motility. EMBO J. 2006;25:5284–5293. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura A, Baumann CA, Chiang SH, Saltiel AR. The sorbin homology domain: a motif for the targeting of proteins to lipid rafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9098–9103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151252898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang M, Maddala R, Rao PV. Novel molecular insights into RhoA GTPase-induced resistance to aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1057–C1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00481.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maddala R, Rao VP. alpha-Crystallin localizes to the leading edges of migrating lens epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao PV, Ho T, Skiba NP, Maddala R. Characterization of lens fiber cell triton insoluble fraction reveals ERM (ezrin, radixin, moesin) proteins as major cytoskeletal-associated proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang M, Kimura A, Saltiel AR. Cloning and characterization of Cbl-associated protein splicing isoforms. Mol Med. 2003;9:18–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zelenka PS. Regulation of cell adhesion and migration in lens development. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:857–865. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041871pz. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. The SH2/SH3 adaptor Grb4 transduces B-ephrin reverse signals. Nature. 2001;413:174–179. doi: 10.1038/35093123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thut CJ, Rountree RB, Hwa M, Kingsley DM. A large-scale in situ screen provides molecular evidence for the induction of eye anterior segment structures by the developing lens. Dev Biol. 2001;231:63–76. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin WH, Huang CJ, Liu MW, et al. Cloning, mapping, and characterization of the human sorbin and SH3 domain containing 1 (SORBS1) gene: a protein associated with c-Abl during insulin signaling in the hepatoma cell line Hep3B. Genomics. 2001;74:12–20. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semina EV, Ferrell RE, Mintz-Hittner HA, et al. A novel homeobox gene PITX3 is mutated in families with autosomal-dominant cataracts and ASMD. Nat Genet. 1998;19:167–170. doi: 10.1038/527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burdon KP, McKay JD, Wirth MG, et al. The PITX3 gene in posterior polar congenital cataract in Australia. Mol Vis. 2006;12:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graw J. Congenital hereditary cataracts. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1031–1044. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041854jg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kioka N, Sakata S, Kawauchi T, et al. Vinexin: a novel vinculin-binding protein with multiple SH3 domains enhances actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:59–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang B, Golemis EA, Kruh GD. ArgBP2, a multiple Src homology 3 domain-containing, Arg/Abl-interacting protein, is phosphorylated in v-Abl-transformed cells and localized in stress fibers and cardiocyte Z-disks. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17542–17550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cestra G, Toomre D, Chang S, De Camilli P. The Abl/Arg substrate ArgBP2/nArgBP2 coordinates the function of multiple regulatory mechanisms converging on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1731–1736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409376102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang M, Liu J, Cheng A, Deyoung SM, Saltiel AR. Identification of CAP as a costameric protein that interacts with filamin C. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4731–4740. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]