Abstract

Heparan sulfate (HS) is a sulfated glycosaminoglycan attached to a core protein on the cell surface. Protein binding to cell surface Heparan sulfate (HS) is a key regulatory event for many cellular processes. The concept whereby protein binding to HS is not random but requires a limited number of sulfation patterns is becoming clear. Here we describe a hydrophobic trapping assay to screen a library of heparin hexasaccharides for binders to Antithrombin III (ATIII). Out of five initial hexasaccharide compositions present in the library (1:2:3:6:1), (1:2:3:7:1), (1:2:3:7:0), (1:2:3:8:0), (1:2:3:9:0) only two are shown to be able to bind ATIII, namely (1:2:3:8:0) and (1:2:3:9:0). The use of an amide hydrophilic interaction (HILIC) LC/MS permitted reproducible quantitative analysis of the composition of the initial library as well as that of the binding fraction. This type of LC/MS has never been applied to heparinoids. The specificity of the hexasaccharides binding ATIII was confirmed by assaying their ability to enhance ATIII mediated inhibition of Factor Xa in vitro.

Introduction

Heparin and heparan sulfate (HS) are a subclass of a heterogeneous family of anionic glycans called glycosaminoglycans. Herparin and HS are made of the repeating disaccharide units HexA β1,4GlcN. The biosynthetic process is initiated by addition of GlcNac to a linker tetrasaccharide (Glucuronic acid-Galactose-Galactose-Xylose) attached to a serine residue of a core protein (1–3). The glycan chain is elongated through addition of glucuronic acid (GlcA)-Nacetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) disaccharides linked by α1,4 glycosidic bonds (4, 5). The polysaccharide chain is further modified by different enzymes while attached to the core protein. In an orderly fashion, the first modification is N-deacetylation/N-sulfation of GlcNAc (6–12) followed by C-5 epimerization of GlcA to Iduronic acid (IdoA) (8, 13–15), 2-O-sulfation of IdoA (16) and 6-O-sulfation of GlcN (17). Because one modified disaccharide serves as a substrate to the next enzyme, the deacetylation, sulfation and epimerization tend to cluster in the same region. The modifying enzymes work only on a fraction of available modification sites and hence the disaccharide compositions of heparin and HS are very heterogeneous. To date, 23 different disaccharides have been identified (18). Although heparin and HS have similar biosynthetic pathways, they markedly differ in the extent of the modifications that they undergo. Heparin, which is synthesized exclusively in mast cells and cleaved from its core protein, undergoes extensive modifications such that more than 85% of the GlcNAc residues are N-deacetylated and N-sulfated and more than 70% of the GlcA is converted to IdoA. In contrast, HS that is found in all tissues and remains attached to the core protein is less modified than heparin. HS is composed of highly sulfated domains resembling heparin called NS-domains and less sulfated domains where GlcNAc remains acetylated called NA domains. The alternation of NS and NA domains makes HS more heterogeneous in sequence than heparin (19).

One of the most important features of heparin/HS is their ability to interact with a wide array of proteins. More than a hundred heparin binding proteins have been discovered and the number is increasing (20). These proteins are involved in a wide range of physiological processes including blood coagulation, cell proliferation, differentiation and migration, cell-cell adhesion, inflammation and pathogen invasion (21). Thus, Heparin/HS exert a regulatory role on these processes by modulating the activity of the proteins with which they interact. A growing body of evidence suggests that binding of proteins to heparins is not random but requires defined sequences within the heparin chain. Based on the knowledge of heparin structure whereby sulfo and carboxyl groups are arranged at defined intervals and in a specific orientation, the general paradigm is that a protein requires a minimal structure that displays optimal functional group arrangement for specific interactions. The specificity of these interactions can be restrictive, meaning that one or a few structures are able to bind the protein or can exhibit more relaxed criteria such that different patterns of substitutions are tolerated (18).

Heparin binding to Anti-thrombin III (ATIII) has been extensively studied and constitutes the paradigm of a restrictive binding. ATIII belongs to the serpin (serine protease inhibitors) superfamily of proteases (22). ATIII reacts with most of the serine proteases of the coagulation cascade to inactivate them by forming 1:1 covalent complexes through interaction between a specific reactive bond on the inhibitor and the active site of the serine protease (23, 24). This inhibition process is enhanced severalfold by the binding of heparin that induces a conformational change in ATIII resulting in stronger inhibition (25). A heparin pentasaccharide is the minimal sequence required to bind ATIII, enhancing its inhibitory activity towards Factor Xa (26–30). The sequence of this pentasaccharide is GlcNAc6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S-IdoA-GlcNS. The two reducing end GlcN are invariably N-sulfated while that at the non reducing end can be either N-acetylated or N-sulfated. The requirements of the functional groups attached to the saccharide residues have been studied in detail. The N-sulfate groups (31), the 6-O sulfate at the non-reducing end (32) and the distinguishing 3-O sulfate (30, 33, 34) on the central GlcN are required for binding and biological activity.

In opposition to the stringent ATIII binding requirement, the binding of growth factor to HS appears to be more relaxed. Fibroblast growth factors (FGF) are the most studied heparin binding proteins after ATIII. The minimal heparin structure binding to FGF2 is a pentamer that contains one or more N and 2-O sulfates with no 6-O sulfation requirement (35). FGF1 binding to HS requires a 5–7 monosaccharide units comprising a critical 2-O, N and 6-O sulfate groups (36).

Despite the increasing understanding that specific heparin/HS sequences mediate the modulation of a growing number of proteins, carbohydrate structures have been elucidated only for a limited number of cases. The heterogeneous and polydisperse nature of heparin/HS combined with the absence of methods to amplify or produce them are the main limiting factors to the acquisition of structural data. Most of the structural analysis methods make use of the available chemical or enzymatic degradation procedures followed by electrophoretic, chromatographic or mass spectrometric detection (37–39). These methods are best applied to purified heparin oligosaccharides in order to produce unambiguous structural assignments. However, in most cases binding sequences consist of a distribution of related structures. In this work, we describe a method that enables the screening and the quantitative analysis of a library of Heparin/HS oligosaccharide for epitopes that are able to bind proteins of interest, using low protein quantities. In order to optimize and test the technique, a readily available and cost effective model system for a heparin binding protein has been used, namely Antithrombin III (ATIII). However, the same principle can be extrapolated to any heparin binding protein. The advantage of this method is its ability to isolate binders in a binary or ternary complexes using low protein quantity.

Materials and method

1. Materials

Porcine intestinal mucosa heparin (sodium salt, 182 USP/mg) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Heparin lyase-I from flavobacterium heparinum was from Ibex (Montreal,Canada). Antithrombin III was a generous gift from GTC Biotherapeutics (Framingham, MA). Amide 80 packing material was obtained from TOSOH Bioscience LLC (Montgomeryville, PA). Actichrome Heparin (anti-FXa) was purchased from American Diagnostica Inc. (Stamford, CT). Δ-disaccharide standard (Di4S) (IdoA-GlcNac4S) was from V-labs (Convington, LA). Arixtra (C31H53N3O49S8) was purchased from Organon Sanofi-Synthelabo LLC (W.Orange, NJ).

2. Construction of heparin hexasaccharide library

Partial digestion of 100 mg porcine intestinal mucosa heparin (Sigma-Aldrich) was performed in 1 ml of 100 mM NH4CH3COO and 0.1mg/ml BSA at 37oC. Heparin Lyase I (150 mU) was added in 6 hour intervals until the digestion reached 30% completion determined using absorbance at 232nm. The digestion was applied to a preparative size exclusion chromatography (SEC) column (170cm × 1.5cm; Biorad, Hercules, CA) packed with polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Gel, P-10, Fine; Biorad) running at ionic content of 200mM NH4HCO3 and a flow rate of 40ul/min (40). Fractions containing the heparin dp6 were combined and desalted by dialysis using 100 Da cutoff.

3. Binding assay

ATIII (1nmol) was incubated with heparin dp6 (100nmol) for 20 minutes in 100 mM NH4CH3COO. The mixture was applied to a Superdex-75 PC 3.2/30 column (Amersham Biosciences; Piscataway, NJ) coupled to a Beckman System Gold 118 solvent module (Fullerton, CA) and the effluent monitored at 232nm. The degassed mobile phase (100mM NH4CH3COO; 3% Acetonitrile) was supplied at 40μl/min. The protein fraction was collected and applied to a C18 reverse phase cartridge (MacroSpin Columns, Silica C18 Vydac, 50–450μl, Harvard Apparatus) after column conditioning as advised by the manufacturer protocol. The bound complex was washed 3 times with 250μl of 200mM NH4CH3COO and the remaining bound sugars eluted with 250 μl of 2M NH4CH3COO.

4. Liquid chromatography/Mass spectrometry (LC/MS)

The heparin hexasaccharides were analyzed in the negative electrospray mode using an Amide-80 hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) online with an Applied Biosystems QSTAR Pulsar-I (Q-ToF) mass spectrometer. The column was packed in house into 250 μm internal diameter × 15cm silica tubing using 5 μm Amide-80 beads. The column was connected to a Waters nanoaquity (Milford, MA) chromatograph operating in the gradient mode with solvent A 50mM Formic acid (pH4.4) and solvent B 95% acetonitrile: 5% A. The compounds were eluted from the column with a gradient starting at 95% and descending to 40% B content over a period of 60 minutes. The mass spectrometer was tuned with Arixtra to minimize the amount of sulfate loss in the source. All runs were repeated in triplicate and mass range calibrated with respect to 1 pmole Di4S internal standard.

5. Actichrome biological activity assay

The high salt elution fraction obtained from the binding assay was dialyzed at 100 Da cutoff and assayed for its biological activity using the Actichrome Heparin (anti-FXa) kit (American Diagnostica Inc., Stamford, CT). The manufacturer protocol was customized by scaling down the recommended volumes ten fold leading to a total reaction volume of 102.5 μl.

Results

To prepare the oligosaccharide library, porcine intestinal mucosa heparin was subjected to partial enzymatic digestion. The digestion mixture was fractionated by preparative size exclusion chromatography and the dp6 fraction collected. A hexasaccharide represents the minimal oligosaccharide that contains an ATIII binding sequence and hence was used as the library to screen for ATIII binders. The library was incubated with ATIII and the protein fraction separated from the unbound oligosaccharides by SEC. An SEC step has also been used to isolate a complex of more that one protein in a ternary complex with a heparin oligosaccharide (41). The collected protein fraction that contains free protein and protein bound to sugars was applied to a reverse phase cartridge and the unspecific binders washed away with low salt concentration (42–44). The specifically bound sugars were eluted using high salt concentration and the composition distribution of the eluted sugars analyzed and quantified by LC/MS. The liquid chromatography adopted uses an amide-silica as the stationary phase. Oligosaccharides are bound to and eluted from this stationary phase with a HILIC mechanism (45). Oligosaccharides are retained based on hydrogen bonding interactions between the amide functionality and the polar hydroxyl groups. When a high to low organic gradient is used, Amide-80 separates oligosaccharides in time based on their polarity and offers the advantage of reproducibility that allows quantification. This matrix has been previously used for LC/MS of chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate oligosaccharides (46, 47) as well as N-glycans (48, 49) but has never been applied to heparinoids.

The compositions of the hexasaccharides library are shown in table 1. The abbreviation of each composition is given under the following format (Hexuronic acid; Hexuronic acid; Glucosamine; sulfate; acetate). Seven different compositions are observed in two categories. The acetylated compositions are (1:2:3:5:1), (1:2:3:6:1), (1:2:3:7:1). The non acetylated compositions are (1:2:3:6:0), (1:2:3:7:0), (1:2:3:8:0), (1:2:3:9:0). The table shows the m/z values only for the unadducted species with error values ranging from −7.3 to 5.6 ppm. This error range typical performance in the negative ion spray mode of heparinoids. Up to four ammonium adducts per ion were observed (data not shown). Two charge states were observed, the doubly and triply negatively charged ions.

Table 1. Hexasaccaride compositions of a 30% heparin digest.

The table shows only the masses of the non adducted compositions.

ΔHexA=unsturated hexuronic acid; HexA= Hexuronic acid; GlcN= Glucosamine; SO3=Sulfate; Ac= Acetyl

| z | Observed m/z | Calculated m/z | Error (ppm) | HexA | HexA | GlcN | SO3 | Ac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 | 725.5406 | 725.5414 | −1.1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| −2 | 765.5241 | 765.5198 | 5.6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| −2 | 805.4923 | 805.4982 | −7.3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| −2 | 744.5175 | 744.5145 | 4.0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| −2 | 784.4913 | 784.4929 | −2.1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| −2 | 824.4711 | 824.4713 | −0.3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 0 |

| −3 | 575.9641 | 575.9641 | 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 0 |

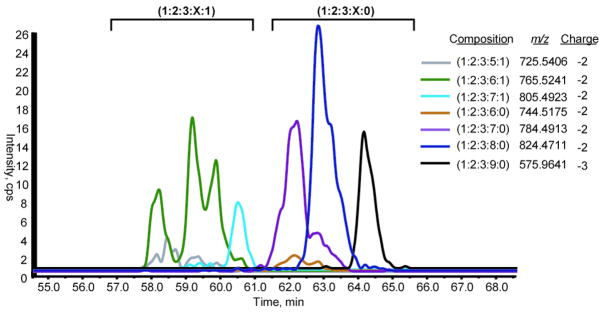

The respective separation of the library hexasaccharides is shown in Figure 1. For both the non acetylated and the acetylated compositions, the general trend of the elution profile is such that the retention time of a composition increases with increasing sulfation content. The resolving power of the column is enough to separate the compounds with the highest but not the least sulfated compositions. The column is able to resolve (1:2:3:7:0), (1:2:3:8:0), (1:2:3:9:0) for the non-acetylated hexasaccharides and (1:2:3:6:1) and (1:2:3:7:1) for the acetylated ones. However, (1:2:3:6:0) and (1:2:3:5:1) show complete overlap with (1:2:3:7:0) and (1:2:3:6:1) respectively. The differential ability of the column to resolve compositions differing by one sulfate addition could be explained if one takes into consideration the in-source loss of sulfate (discussed later). In fact, the (1:2:3:6:0) and (1:2:3:5:1) compositions might possibly be loss of sulfate fragmentation products of (1:2:3:7:0) and (1:2:3:6:1) respectively and hence show the same retention times. Additionally, the nature of the interaction with the stationary phase might be influenced by the spatial distribution of these groups along the oligosaccharide chain (isomerization).

Figure 1. Amide-80 chromatographic separation of the different heparin hexasaccharides.

The Amid-80 separates the heparin hexasaccharides according to their polarity. The acetylated category (1:2:3:X:1) elutes at a higher organic content of the gradient compared to the unacetylated category (1:2:3:X:0).Within each category, the general trend is such that the more sulfated compositions display higher retention times. The figure shows the extracted in chromatograms of the non adducted compositions.

In the XIC of (1:2:3:6:1) (m/z =765.5241 Da), three peaks can be observed at different retention times, 58.0, 59.2 and 59.8 minutes. This profile was reproducible over three replicates. The comparison of the m/z spectra of each of these peaks separately shows the following. The major peak in the spectra of the peaks at 59.2 and 59.8 min was the expected one at m/z = 765.5241 Da and may represent structural isomers that are differentially retained on the amide-80 column. Surprisingly, in the spectrum of the peak at 58.0 minutes, the major peak was at an m/z of 765.0260 Da. This latter mass is consistent with the glycosylamine corresponding to the (1:2:3:6:1) composition with an error of −2.3 ppm. Hence, the XIC of the (1:2:3:6:1) composition shown in Fig 1 is in fact tracing two different compositions, the (1:2:3:6:1) and its corresponding glycosylamine. The conversion into a glycosylamine derivative and the presence of multiple isomers both contribute to the multiple peak elution profile of the (1:2:3:6:1) composition. Glycosylamine formation is a general phenomenon for acetylated heparin oligosaccharides and has not been observed for non-acetylated compositions(50).

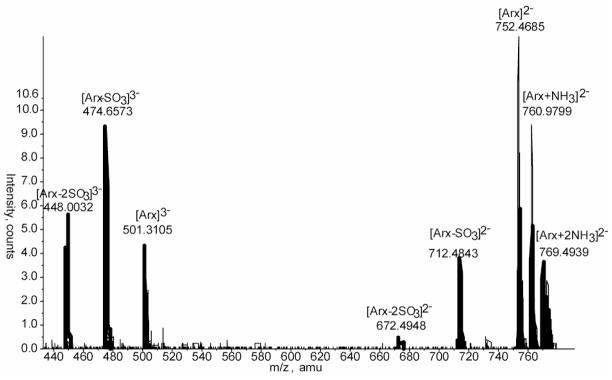

In-source loss of sulfate analysis was undertaken by studying the ionization properties of a sulfated standard, Arixtra. This octasulfated pentasaccharide methylglycoside of known composition (C31H53O49S8) and theoretical molecular mass of 1506.9513 Daltons is very pure. Its chemical properties make it a good candidate to mimic the behavior of heparin hexasaccharides and hence allow estimating the degree of sulfate loss that occurs in source. Figure 2 shows the mass spectrum of Arixtra summed from an LC/MS dataset where the doubly charged, triply charged and sodium and ammonium adducted species are detected. Both the doubly charged (m/z=752.4685) and the triply charged (m/z=501.3105) ions show fragmentation products generated by loss of one or two sulfate groups. Quantitative analysis of sulfate loss estimates the degree of fragmentation to 16.0% and 4.2% for one and two sulfates respectively. The degree of sulfate loss is difficult to model because it depends on the concentration and charge state.

Figure 2. Negative ESI MS of Arixtra.

The figure shows the LC/MS spectrum of Arixtra. The doubly (m/z= 752.4685 Da;0.15ppm) and triply charged (m/z= 501.3105 Da; 1.3ppm) ions are shown. Arixtra undergoes loss of one and two sulfates as revealed by the peaks at lower m/z.

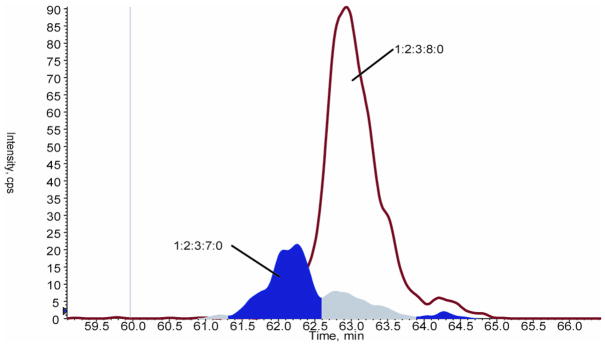

The online chromatography system enables correction for the in-source sulfate losses. Quantification of the relative abundances of the different compositions only by integration of areas under the peaks would be an overestimation because it fails to exclude the contribution of sulfate loss. The observed peak profile for a composition (1:2:3:X:Y) represents a combination the structure existing in solution and the sulfate loss fragmentation products of (1:2:3:X+1:Y) and (1:2:3:X+2:Y). Chromatographic resolution of these compositions was used to correct for the contribution of sulfate loss during the quantification of the relative abundances of the various compositions. Since the Arixtra mass spectrum (Figure 2) shows negligible loss of two sulfates, we only focused on single sulfate loss. The assumption for the quantification method is that compositions of different sulfate contents are resolved by the column and therefore peaks that overlap in elution time are the same. Figure 3 shows the extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) for the hexasaccharide (1:2:3:7:0) and the integration under the curve. In this curve, three peaks are clearly identifiable at respective approximate elution times 62.25 and 62.65 and 64.25 min. Superimposition of the (1:2:3:7:0) XIC onto those of the (1:2:3:8:0) shows that the peak at 62.25 min is separated in time with respect to the (1:2:3:8:0). In contrast, the peaks at 62.65 and 64.25 minutes follow the elution profile of (1:2:3:8:0). Hence, according to the previous assumptions, the peaks at 62.65 and 64.25 minutes represent the fraction of the (1:2:3:8:0) that has lost a sulfate and contributed to the (1:2:3:7:0). Therefore, when quantifying the abundance of the (1:2:3:7:0), only the peak at 62.25 minutes will be considered and the two other peaks at 62.65 and 64.25 min will be added abundance of (1:2:3:8:0). Therefore, the total overlap seen in figure 1 between (1:2:3:6:0) and (1:2:3:7:0) on one hand and (1:2:3:5:1) and (1:2:3:6:1) on the other means that former compositions are loss of sulfate products of the latter.

Figure 3. Fragmentation of (1:2:3:8:0) into (1:2:3:7:0).

The XIC of the (1:2:3:7:0) composition is superimposed over that of the (1:2:3:8:0). Three peaks are identifiable in the XIC of (1:2:3:7:0) at respective retention times 62, 63 and 64.3 minutes. The peaks at 63 and 64.3 minutes overlap totally and follow the profile of the (1:2:3:8:0) composition. Hence, they are considered loss of sulfate products of the (1:2:3:8:0). During the calculation of relative abundance, the highlighted integrated areas under these two peaks are added to the area under the XIC of (1:2:3:8:0).

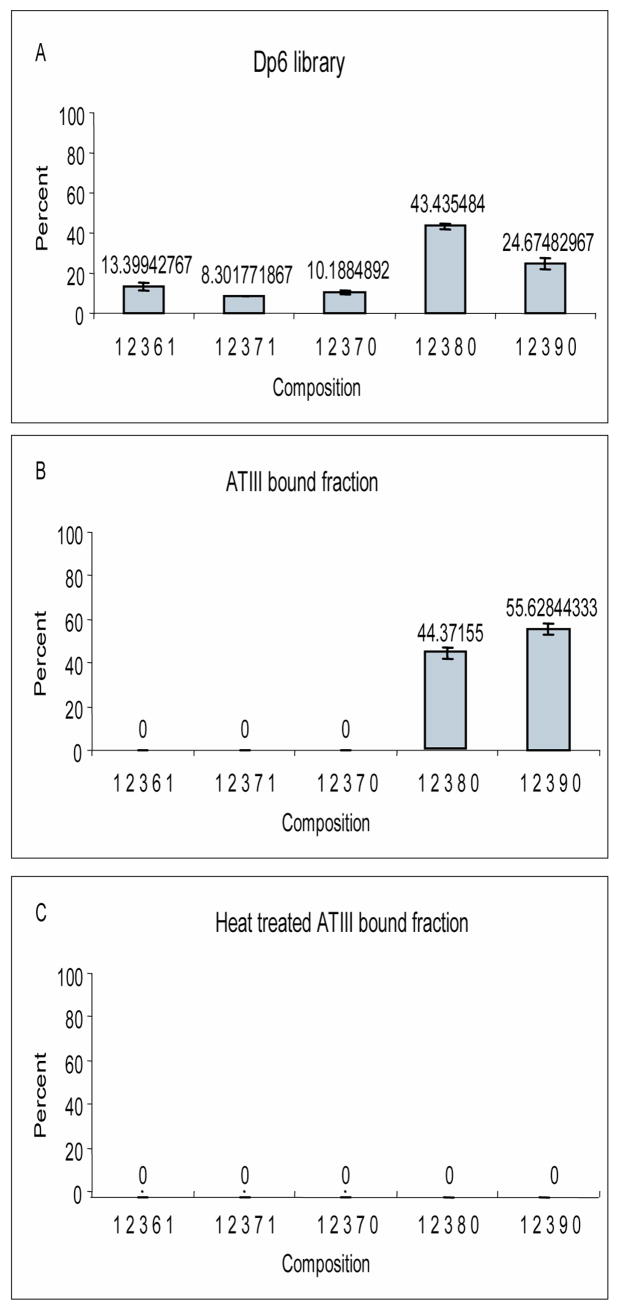

The method was used to correct the relative abundances of the different compositions in the heparin dp6 library. Figure 4A shows the compositions identified and their relative abundances. Five different hexasaccharide compositions are generated after partial digestion, namely (1:2:3:6:1), (1:2:3:7:1), (1:2:3:7:0), (1:2:3:8:0), (1:2:3:9:0). The non acetylated hexasaccharides with 8 and 9 sulfates respectively are the most abundant compositions, together accounting for 68.1% of the total generated hexasaccharides.

Figure 4. Quantification of the relative abundances of heparin hexasaccharide.

A. Relative abundances of the different hexasaccharides present in the dp6 library. Analysis was done in triplicates.

B. Relative abundances of the different hexasaccharides present in the bound fraction (2M ammonium acetate elution fraction). Analysis was done in triplicates.

C. Relative abundances of the different hexasaccharides present in the bound fraction of a heat inactivated ATIII. Analysis was done in triplicates.

Analysis of the high salt elution fraction (termed bound fraction) by LC/MS shows that when the initial library is subjected to the workup protocol, it undergoes drastic compositional change. The bound hexasaccharides are the non-acetylated and the most highly sulfated ones, namely (1:2:3:8:0) and (1:2:3:9:0) (figure 4B). The quantification of the relative abundances of the bound compositions reveals that, the (1:2:3:8:0) accounts for 44.3% while the (1:2:3:9:0) represents for 55.6% of the total (figure 4B). Two experiments were done to rule out non-specific binding. First, the exact binding protocol was repeated using ATIII that was heat inactivated and subsequently mixed with heparin dp6 library to isolate binders (Figure 4C). Second, the active ATIII protein was mixed with unspecific Chondroitin sulfate B hexasaccharide (Data not shown). Any oligosaccharides collected in the bound fraction of these experiments will be retained to the final step of the protocol due to unspecific binding. Analysis of the bound fraction yielded by these two experiments by LC/MS did not show peaks with m/z values corresponding to hexasaccharides (Figure 4C and data not shown).

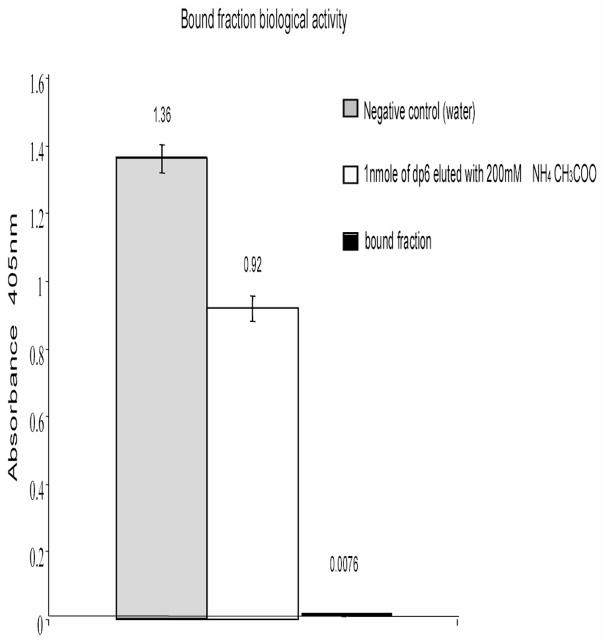

In order to further prove that the hexasaccharides obtained in the high salt elution step (bound fraction) were not a result of the failure of the protocol to eliminate unspecific binders and hence prove their specific interaction with ATIII, we tested its ability to modulate ATIII activity compared to the oligosaccharides collected in the low salt (200mM NH4CH3COO wash fraction). The activity of the bound fraction was assayed by measuring its ability to enhance the ATIII inhibitory effect on factor Xa using the Actichrome heparin (antiFXa) kit. In this kit, the proteolyitc activity of excess FXa is assayed by incubating it with a substrate yielding a chromogenic product that absorbs at 405nm. When ATIII and heparin are added to the reaction, a fraction of the FXa is neutralized and the 405 nm absorbance measured is representative of the residual FXa activity. Hence, the resulting spectrophotometric signal is inversely proportional to the heparin activity in the sample. The ability of the heparin hexasaccharide bound fraction to inhibit FXa was assayed and compared to the wash fraction (Figure 5). Because the bound hexasaccharides were not quantified, their activity was compared to an excess of non-binders (1 nanomole). The hexasaccharides in the high salt elution fraction showed significantly higher potency in triggering the ATIII mediated inhibition of FXa compared to the wash fraction.

Figure 5. The Anti-FXA activity of the bound fraction eluted with 2M ammonium acetate.

The ATIII mediated inhibitory activity of heparin hexasaccharides on FXa was studied using a colorimetric assay. FXa is able to hydrolyze a synthetic substrate yielding a colored product detected at 405nm. When FXa is incubated with its substrate in the presence of ATIII and heparin its hydrolytic activity is inhibited. The 405nm absorbance is inversely related to the anti-FXa activity of heparin used in the experiments. Experiments were done in triplicates.

Discussion

In this work, ATIII binding to heparin hexasaccharides is used as a model in order to optimize an SEC-hydrophobic trapping method for consumption of a low (1nmol) quantity of protein. Low protein consumption is critical for eventual application to growth factor heparin binding. We have used a library of heparin hexasaccharides as those represent the smallest oligosaccharides containing an ATIII binding site. Compositional analysis of this library at high mass accuracy has been done after correction for the in-source loss of sulfate. The correction for sulfate loss was facilitated by using an amide-80 HILIC LC/MS system that separates the hexasaccharides based on their polar character. As the polarity of a molecule increases, it is retained longer by the column and elutes at a higher polar content of the gradient. The differential polarity of heparin oligosaccharides is mainly dictated by the number of hydroxyl, sulfate and acetyl groups they contain. The polar character varies directly with sulfation and indirectly with acetylation. The analysis revealed five different compositions, (1:2:3:6:1), (1:2:3:7:1), (1:2:3:7:0), (1:2:3:8:0), (1:2:3:9:0). One acetylated composition, the (1:2:3:6:1), was further modified into the corresponding glycosylamine. The formation of glycosylamines results from the protocol of generation of heparin hexasaccharides. The partial heparin digestion is separated into different size fractions on a preparative SEC column running with 200mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer. As the dp6 fractions are combined and dried, they are constantly in presence of increasing ammonium ions concentration. These conditions are known to favor the formation of glycosylamines (51). From our practical experience with working with heparin, we have observed the formation of glycosylamines derivatives only with acetylated heparin oligosaccharides. The tendency of formation of these derivatives varies inversely with the number of sulfates on an oligosaccharide. This might explain why other acetylated hexasaccharides with higher sulfation do not undergo conversion to glycosylamines.

The analysis of the results using the novel amide-80 based LC/MS method has permitted more accurate quantification of the results obtained. Taking the complexity of a heparin sample, direct quantification of the different compositions by static negative nano electrospray ionization (ESI) MS is a difficult task due to the irreproducibility of the spectra obtained. Addition of the liquid chromatography component prior to the MS step offered the advantage of reproducibility for the quantification of the different compositions of heparin hexasaccharides. The degree of reproducibility over triplicate experiments ranged between 0.03–2.7 percent.

The ATIII binding fraction that was eluted with high salt is composed of the two following unacetylated compositions (1:2:3:8:0) and (1:2:3:9:0). While the (1:2:3:8:0) represents the most abundant composition in the initial library with a relative abundance of 43.3%, the (1:2:3:9:0) composition becomes the predominant one in the bound fraction accounting for 55.6% of the total. Original publications using heparin hexasaccharides library generated by nitrous acid cleavage recovered binders carrying both N-sulfate and N-acetate at the non reducing GlcN (26). It is now known, that the non reducing N-Acetyl group is not essential for ATIII binding (28) and these results are confirmed by chemical synthesis. A synthetic pentasaccharide where the N-acetyl group of the non reducing GlcN was replaced by an N-sulfate has a Kd of 50 nM for ATIII (compared to a Kd of 80nM for the N-acetylated pentasaccharide and an enhanced anti-FXa activity)(52). The absence of acetylated compositions in the bound fractions of this work indicates that those components, if present in the bound fraction, are under the limit of detection of the mass spectrometer used.

The evidence that the high salt elution fraction is specific was confirmed via several experiments. The results confirm that the devised protocol is able to eliminate any binding that is not dependant on the biological activity of ATIII or specific heparin sequence that binds ATIII. In addition, this fraction was assayed for its anti-FXa activity and this activity compared to low salt wash fraction. The observation that the high salt fraction has significantly higher activity compared to the unspecific low salt wash fraction strongly supports the conclusion that the (1:2:3:8:0) and (1:2:3:9:0) compositions are specific binders.

The method discussed in this work aims at solving the challenging task of determination of protein binding heparin oligosaccharides. Although ATIII is used as a model system, the method can be applied to any heparin binding protein using low protein quantities. Some other proteins of interest belong to the growth factors family. Variation in the structures of HS on cell surfaces and the extracellular matrix is a mechanism whereby cellular responses to growth factor stimulation are modulated. This method will enable progress in the understanding of heparin/HS expression and growth factor binding.

Abbreviations

- HS

heparan sulfate

- HexA

Hexuronic acid

- ΔHexA

unsturated hexuronic

- GlcN

Glucosamine

- GlcA

Glucuronic acid

- IdoA

Iduronic acid

- GlcNAc

Nacetylglucoasamine

- ATIII

Antithrombin III

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- Dp

degree of polymerization

- HILIC

Hydrophilic interaction chromatography

- XIC

Extracted ion chromatogram

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

Footnotes

Funding from NIH grants R01HI74197 and P41RR10888 is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Lindahl U, Roden L. The linkage of heparin to protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1964;17:254–259. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(64)90393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl U, Roden L. The Role of Galactose and Xylose in the Linkage of Heparin to Protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1965;240:2821–2826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindahl U, Cifonelli JA, Lindahl B, Roden L. The Role of Serine in the Linkage of Heparin to Protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1965;240:2817–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsee WT, Roden L. Biosynthesis of heparin. Transfer of N-acetylglucosamine to heparan sulfate oligosaccharides. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1981;256:7240–7247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lind T, Lindahl U, Lidholt K. Biosynthesis of heparin/heparan sulfate. Identification of a 70-kDa protein catalyzing both the D-glucuronosyl- and the N-acetyl-D-glucosaminyltransferase reactions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:20705–20708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navia JL, Riesenfeld J, Vann WF, Lindahl U, Roden L. Assay of N-acetylheparosan deacetylase with a capsular polysaccharide from Escherichia coli K5 as substrate. Analytical biochemistry. 1983;135:134–140. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl U, Backstrom G, Jansson L, Hallen A. Biosynthesis of heparin. II Formation of sulfamino groups. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1973;248:7234–7241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riesenfeld J, Hook M, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. Assay and properties of the microsomal N-acetyl-D-glucosaminyl N-deacetylase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1980;255:922–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riesenfeld J, Hook M, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. Concerted action of early polymer-modification reactions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1982;257:421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusche M, Hannesson HH, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. Use of Escherichia coli K5 capsular polysaccharide as a model substrate in enzymic polymer-modification reactions. The Biochemical journal. 1991;275(Pt 1):151–158. doi: 10.1042/bj2750151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bame KJ, Reddy RV, Esko JD. Coupling of N-deacetylation and N-sulfation in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant defective in heparan sulfate N-sulfotransferase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:12461–12468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lidholt K, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. The D-glucuronosyl- and N-acetyl-D-glucosaminyltransferase reactions and their relation to polymer modification. The Biochemical journal. 1992;287(Pt 1):21–29. doi: 10.1042/bj2870021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindahl U, Backstrom G, Malmstrom A, Fransson LA. Biosynthesis of L-iduronic acid in heparin: epimerization of D-glucuronic acid on the polymer level. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1972;46:985–991. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hook M, Lindahl U, Backstrom G, Malmstrom A, Fransson L. Biosynthesis of heparin. 3 Formation of iduronic acid residues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1974;249:3908–3915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malmstrom A, Roden L, Feingold DS, Jacobsson I, Backstrom G, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. Partial purification of the uronosyl C-5 epimerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1980;255:3878–3883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusche M, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. O-sulfation of D-glucuronic acid units. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:15403–15409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsson I, Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. Concerted action of late polymer-modification reactions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1980;255:5094–5100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esko JD, Selleck SB. Order out of chaos: assembly of ligand binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annual review of biochemistry. 2002;71:435–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, Freeze H, Hart G, Marth G. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conrad HE. Heparin Binding Proteins. Academic Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capila I, Linhardt RJ. Heparin-protein interactions. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. 2002;41:391–412. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<390::aid-anie390>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldsmith EJ, Mottonen J. Serpins: the uncut version. Structure. 1994;2:241–244. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damus PS, Hicks M, Rosenberg RD. Anticoagulant action of heparin. Nature. 1973;246:355–357. doi: 10.1038/246355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjork I, Ylinenjarvi K, Olson ST, Bock PE. Conversion of antithrombin from an inhibitor of thrombin to a substrate with reduced heparin affinity and enhanced conformational stability by binding of a tetradecapeptide corresponding to the P1 to P14 region of the putative reactive bond loop of the inhibitor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:1976–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villanueva G, Danishefsky I. Conformational changes accompanying the binding of antithrombin III to thrombin. Biochemistry. 1979;18:810–817. doi: 10.1021/bi00572a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindahl U, Thunberg L, Backstrom G, Riesenfeld J, Nordling K, Bjork I. Extension and structural variability of the antithrombin-binding sequence in heparin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1984;259:12368–12376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casu B, Oreste P, Torri G, Zoppetti G, Choay J, Lormeau JC, Petitou M, Sinay P. The structure of heparin oligosaccharide fragments with high anti-(factor Xa) activity containing the minimal antithrombin III-binding sequence. Chemical and 13C nuclear-magnetic-resonance studies. The Biochemical journal. 1981;197:599–609. doi: 10.1042/bj1970599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thunberg L, Backstrom G, Lindahl U. Further characterization of the antithrombin-binding sequence in heparin. Carbohydrate research. 1982;100:393–410. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)81050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atha DH, Stephens AW, Rimon A, Rosenberg RD. Sequence variation in heparin octasaccharides with high affinity for antithrombin III. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5801–5812. doi: 10.1021/bi00319a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atha DH, Lormeau JC, Petitou M, Rosenberg RD, Choay J. Contribution of monosaccharide residues in heparin binding to antithrombin III. Biochemistry. 1985;24:6723–6729. doi: 10.1021/bi00344a063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riesenfeld J, Thunberg L, Hook M, Lindahl U. The antithrombin-binding sequence of heparin. Location of essential N-sulfate groups. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1981;256:2389–2394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindahl U, Backstrom G, Thunberg L. The antithrombin-binding sequence in heparin. Identification of an essential 6-O-sulfate group. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1983;258:9826–9830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindahl U, Backstrom G, Thunberg L, Leder IG. Evidence for a 3-O-sulfated D-glucosamine residue in the antithrombin-binding sequence of heparin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77:6551–6555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Lederman I, Choay J, Sinay P. Binding of heparin to antithrombin III: a chemical proof of the critical role played by a 3-sulfated 2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose residue. Carbohydrate research. 1988;179:163–172. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maccarana M, Casu B, Lindahl U. Minimal sequence in heparin/heparan sulfate required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:23898–23905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreuger J, Prydz K, Pettersson RF, Lindahl U, Salmivirta M. Characterization of fibroblast growth factor 1 binding heparan sulfate domain. Glycobiology. 1999;9:723–729. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.7.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turnbull JE, Hopwood JJ, Gallagher JT. A strategy for rapid sequencing of heparan sulfate and heparin saccharides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:2698–2703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venkataraman G, Shriver Z, Raman R, Sasisekharan R. Sequencing complex polysaccharides. Science (New York, NY. 1999;286:537–542. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vives RR, Pye DA, Salmivirta M, Hopwood JJ, Lindahl U, Gallagher JT. Sequence analysis of heparan sulphate and heparin oligosaccharides. The Biochemical journal. 1999;339(Pt 3):767–773. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziegler A, Zaia J. Size-exclusion chromatography of heparin oligosaccharides at high and low pressure. Journal of chromatography. 2006;837:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harmer NJ, Robinson CJ, Adam LE, Ilag LL, Robinson CV, Gallagher JT, Blundell TL. Multimers of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-FGF receptor-saccharide complex are formed on long oligomers of heparin. The Biochemical journal. 2006;393:741–748. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Y, Sweeney MD, Saad OM, Crown SE, Hsu AR, Handel TM, Leary JA. Chemokine-glycosaminoglycan binding: specificity for CCR2 ligand binding to highly sulfated oligosaccharides using FTICR mass spectrometry. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:32200–32208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sweeney MD, Yu Y, Leary JA. Effects of sulfate position on heparin octasaccharide binding to CCL2 examined by tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2006;17:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schenauer MR, Yu Y, Sweeney MD, Leary JA. CCR2 chemokines bind selectively to acetylated heparan sulfate octasaccharides. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alpert AJ, Shukla M, Shukla AK, Zieske LR, Yuen SW, Ferguson MA, Mehlert A, Pauly M, Orlando R. Hydrophilic-interaction chromatography of complex carbohydrates. J Chromatogr A. 1994;676:191–122. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akiyama H, Shidawara S, Mada A, Toyoda H, Toida T, Imanari T. Chemiluminescence high-performance liquid chromatography for the determination of hyaluronic acid. chondroitin sulphate and dermatan sulphate, Journal of chromatography. 1992;579:203–207. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hitchcock AM, Yates KE, Costello CE, Zaia J. Comparative glycomics of connective tissue glycosaminoglycans. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007 doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700787. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wuhrer M, Koeleman CA, Deelder AM, Hokke CH. Normal-phase nanoscale liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry of underivatized oligosaccharides at low-femtomole sensitivity. Analytical chemistry. 2004;76:833–838. doi: 10.1021/ac034936c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wuhrer M, Koeleman CA, Hokke CH, Deelder AM. Protein glycosylation analyzed by normal-phase nano-liquid chromatography--mass spectrometry of glycopeptides. Analytical chemistry. 2005;77:886–894. doi: 10.1021/ac048619x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bowman Michael J, CEC, Hitchcock Alicia M, Lau James M, Leymarie Nancy, Miller Christine, Naimy Hicham, Shi Xiaofeng, Staples Gregory O, Zaia Joseph. A chip-based Amide-HILIC LC/MS Platform for Glycosaminoglycan Glycomics. 2007 doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701008. In preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manger ID, Rademacher TW, Dwek RA. 1-N-glycyl beta-oligosaccharide derivatives as stable intermediates for the formation of glycoconjugate probes. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10724–10732. doi: 10.1021/bi00159a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petitou M, Lormeau JC, Choay J. Chemical synthesis of glycosaminoglycans: new approaches to antithrombotic drugs. Nature. 1991;350:30–33. doi: 10.1038/350030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]