Abstract

Heroin addiction is a chronic complex disease with a substantial genetic contribution. This study was designed to identify gene variants associated with heroin addiction in African Americans. The emphasis was on genes involved in reward modulation, behavioral control, cognitive function, signal transduction, and stress response. We have performed a case-control association analysis by screening with 1350 variants of 130 genes. The sample consisted of 202 former severe heroin addicts in methadone treatment and 167 healthy controls with no history of drug abuse. Single-SNP, haplotype and multi-SNP genotype pattern analyses were performed. Seventeen SNPs showed point-wise significant association with heroin addiction (nominal P < 0.01). These SNPs are from genes encoding several receptors: adrenergic (ADRA1A), arginine vasopressin (AVPR1A), cholinergic (CHRM2), dopamine (DRD1), GABA-A (GABRB3), glutamate (GRIN2A), and serotonin (HTR3A), as well as alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH7), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD1 and GAD2), the nucleoside transporter (SLC29A1), and diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI). The most significant result of the analyses was obtained for the GRIN2A haplotype G-A-T (rs4587976-rs1071502-rs1366076) with protective effect (P uncorrected = 9.6E-05, P corrected = 0.058). This study corroborates several reported associations with alcohol and drug addiction as well as other related disorders, and extends the list of variants that may affect the development of heroin addiction. Further studies will be necessary to replicate these associations and to elucidate the roles of these variants in drug addiction vulnerability.

Keywords: association study, heroin addiction, polymorphisms, African Americans, NMDA glutamate receptor

Introduction

Heroin addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by drug dependence, tolerance and compulsive seeking and use despite harmful consequences. This complex disorder is a worldwide major public health problem. The relatively high heritability (40-60%) of this disorder (Tsuang et al., 1996) indicates that genetic variants may play a role in vulnerability to its development. Chronic drug use alters gene expression, which activates or attenuates biochemical pathways and produces neuroadaptive changes in signal transduction functions. Identifying these variants is important for the understanding of the possible causes of this disease and to improve its diagnosis and treatment, as well as for primary prevention purposes.

Studies have suggested association of a number of gene variants with heroin addiction or combined drug addiction. These include variants in genes encoding opioid, dopamine, serotonin, and GABA receptors and also cholinergic muscarinic 2, ACTH, and cannabinoid 1 receptors. In addition, association was suggested for catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), period circadian protein 3, proenkephalin, proopiomelanocortin, tryptophan hydroxylase 2, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Kreek et al., 2005, Cheng et al., 2005, Loh et al., 2007, Nielsen et al., 2008, Proudnikov et al., 2008, Proudnikov et al., 2006, Szilagyi et al., 2005, Xu et al., 2004, Zou et al., 2007, Zuo et al., 2007)}. We have recently conducted a candidate gene association study in European Americans (EA), in which we detected associations with SNPs in OPRM1, OPRK1 OPRD1, GAL, HTR3B and CSNK1E, with severe heroin addiction (Levran et al., 2008)

Specific disease-associated genetic factors may vary in frequency among populations because of random drift or natural selection (Lohmueller et al., 2006). The degree and pattern of linkage disequilibrium (LD) also differ among populations. In addition, some functional variants may have different effects in different ethnic groups (Tate & Goldstein, 2004).

We performed a hypothesis -driven case-control association study, using an “addiction-focused” SNP array (Hodgkinson et al., 2008) in African Americans (AA) that extends our original study in EA (Levran et al., 2008). The two populations were separated for analysis based on significant differences in allele frequencies and the vulnerabilities of these studies to population stratification. The cases were selected from the extreme margin of the specific phenotype range (e.g., severe heroin addicts in methadone maintenance treatment) and the controls were selected by detailed personal interview and stringent criteria.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Three hundred and sixty nine subjects participated in the study (202 cases and 167 controls). There were 54% percent females in the control group and 38% in the case group. The mean age at recruitment was 31.9 (±11.7) years in the control group and 47.0 (±8.8) years in the case group. The patients (cases) were former severe heroin addicts from methadone maintenance treatment programs. Subjects were recruited at the Rockefeller University Hospital, the Manhattan Campus of the VA NY Harbor Health Care System, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Clinic for Drug Abuse Treatment and Research, Las Vegas. Ascertainment was made by personal interview, using several instruments: the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (Mclellan et al., 1992), the Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellogg scale (KMSK) (Kellogg et al., 2003), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV). All subjects had a history of using heroin multiple times per day, every day for at least one year. The 167 control subjects were recruited at the Rockefeller University Hospital. Each of the following was used as an exclusion criterion from this category: a) At least one instance of drinking to intoxication, or any illicit drug use, in the previous 30 days. b) A past history of alcohol drinking to intoxication, or illicit drug use, more than twice a week, for more than six consecutive months. c) Cannabis use for more than 12 days in the prior 30 days or past use for more than twice a week for more than 4 years. All subjects completed a family history questionnaire and were self-identified as AA for three generations. Participants were excluded from the study if they had a relative in the study, or had a mixed ancestry. The Institutional Review Boards of Rockefeller University, VA NY and Cornell University approved the study. Rockefeller University IRB also reviews the Adeslon Clinic, Las Vegas.. All subjects signed informed consent for genetic studies.

DNA preparation

Blood samples were taken and DNA was extracted using the standard salting-out method. DNA was quantified using PicoGreen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 700 ng DNA (45 μL) was ethanol-precipitated for a second time and re-suspended in 7 μl Tris-EDTA (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) as described (Levran et al., 2008). 5 μl (250-500 ng) were used for genotyping.

Genotyping and quality assessment

Genotyping was performed on a 1,536-plex GoldenGate Custom Panel (GS0007064-OPA, Illumina, San Diego, CA). 1350 SNPs were selected from 130 candidate genes (Hodgkinson et al., 2008). In addition, the array included 186 ancestry informative markers (AIMs) that were selected based on allele frequencies in the European, African and Chinese population of the HapMap project (Enoch et al., 2006, Hodgkinson et al., 2008). Genotyping was performed at the Rockefeller University Genomics Resource Center according to the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina). Analysis was performed using BeadStudio genotyping software (Illumina). Genotype data was filtered based on SNP call rates (>99.5%), MAF>0.01, cluster separation score, and deviation from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE). Random samples (~10%) were genotyped in duplicate and two identical samples were genotyped on each of the arrays for reproducibility control purposes.

Statistical analysis

Population stratification

Ancestry informative markers were employed to test for population stratification using the STRUCTURE v2.2 software (Pritchard et al., 2000). This software places individuals in K clusters of potential putative populations separated by marker frequencies. A no-admixture ancestry model with K set to 1 was initially used to infer the Dirichlet parameter lambda of the distribution of allele frequencies. The value of lambda thus obtained was later used under an admixture model with allele frequencies correlated using a burn-in length of 50,000 followed by 50,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo iterations which was sufficient to yield stable results.

STRUCTURE was also used to compare the AA sample in this study with the EA sample analyzed in a recent study (Levran et al., 2008). Although two clear clusters were observed, K was set to 3 for better display of the results in the yielded triangle plot. The coordinates of any given point in this triangle are given by the relative distance to each edge (putative population). Individuals who are in one of the corners are therefore assigned completely to a particular population.

The genomic control method (Devlin et al., 2001) was used to estimate the degree of subdivision in our study sample. In this method, markers are used to estimate the background association which can then be used to infer the variance inflation factor, lambda, introduced when there is subdivision.

Association Analysis

The frequency of marker alleles and genotypes in cases and controls were compared using Fisher's exact test, as implemented in R v2.7.0 (http://www.R-project.org). This test was preferred over a parametric test since there were numerous instances of small cell counts in the tables. This test was also used to estimate allelic odds ratios (OR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The most significant results were also evaluated using the chi-square test and no substantial differences were found. An uncorrected P-value of 0.01 was chosen as the threshold for point-wise significance for the association tests.

Marker genotype quality control was performed in the control sample by using the exact test of deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg (DHW) proportions as implemented in the R package Genetics Base v1.6.0 (http://rgenetics.org/). This test estimates allelic correlations occurring at the locus level which may be caused by genotyping errors. The DHW test is not powerful enough to detect deviations caused by small error rates but can be used to detect gross genotyping errors which can cause large DHW. For this reason, a conservative p-value of 0.05/1114 = 0.000045 was used as a cut-off for declaring significant departures from HW proportions.

To adjust for possible age and gender effects, a logistic regression analysis was run on the set of markers using PLINK v1.05 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/)

Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) Blocks, Haplotype Analysis and Genotype Patterns

The pattern of pair-wise LD between SNPs was measured by the standardized disequilibrium value (D') as implemented in Haploview v4.1 (Barrett et al., 2005). In order to capture the blocks that consist of the specific SNPs indicated in the single SNP association tests, LD haplotype blocks were identified using the Gabriel's method (Gabriel et al., 2002). When no block was identified by this method, the alternative solid spine of LD definition (Barrett et al., 2005) was employed.

Haplotypes were reconstructed using the accelerated expectation-maximization algorithm implemented in Haploview for genes that include at least one marker whose P-value was less than 0.01 in the single-locus association test. Haplotype association analysis was performed for each of the reconstructed haplotypes (against the rest) using the Fisher's exact test. Multi-locus genotype patterns (MLGP) of the markers in the blocks identified by Haploview were determined. For a set of a given number m SNPs, n observed m locus genotype pattern frequencies were stored in an n x 2 contingency table where the two columns corresponded to cases and controls. A Fisher's exact test for differences in MLGP frequencies between the two groups was performed. In addition to single-locus effects, MLGP analysis also evaluates epistatic interaction influencing the outcome. Since we are not interested in the effects of rare genotype patterns, in this analysis, pattern frequencies below 5% in cases and controls each were pooled into a single “rare” class.

Multiple Testing Corrections

Results were adjusted for multiple testing by using the R package QVALUE v1.1 (Storey, 2003, Storey & Tibshirani, 2003). Rather than dealing with the probability of rejecting a true null hypothesis (the family-wise error rate), the approach implemented in QVALUE estimates the expected proportion of false positives among all rejected hypotheses (the false discovery rate, FDR) (Benjamini et al., 2001). QVALUE takes a given set of P values and, for each test, estimates the minimum FDR that is incurred when calling that particular test significant (the q-value of the test). The q-value measures the significance of each of a family of tests performed simultaneously and holds under different forms of dependence. The smallest nominal P value of all tests performed (Pmin) was observed from the haplotype association tests. The QVALUE program was run on the list of P values created by adding Pmin to the set of P values obtained from the single-locus tests. The result is the estimated experiment-wise significance of Pmin. An FDR of 0.05 was used as the significance level.

Results

Genotype and allele frequencies of 1194 SNPs from 130 candidate genes (Hodgkinson et al., 2008) were analyzed for association with heroin addiction in 369 AA samples (202 cases and 167 controls). One hundred fifty six SNPs were excluded from analysis because of inadequate quality (cluster separation score < 0.4), low variability (MAF < 0.01) (Table S1), or deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the control sample. Genotyping reproducibility was 99.9% and the mean marker call rate after exclusion was 99.8%.

Association analysis

Results of the most significant single SNP association tests are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Indication of association with heroin addiction was observed with seventeen SNPs (uncorrected P < 0.01) in the following genes: glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) subtype 2A, solute carrier family 29 (nucleoside transporters) member 1, dopamine receptor D1, alcohol dehydrogenase isozyme 7, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, serotonin) receptor, subtype 3A, glutamate decarboxylase isoforms 1 and 2, GABA-A receptor, subunit beta 3, diazepam binding inhibitor, cholinergic receptor, muscarinic 2, adrenergic receptor alpha-1A, and arginine vasopressin receptor subtype 1A. Listed in Table S2 are the alleles and genotype frequencies in cases and controls. Odds ratios were calculated for the minor allele and indicate a small effect (OR for risk effect range 1.54-1.94 and OR for a protective effect range 0.16-0.66 for the allelic test, Table 2). None of the tests were significant after correction for multiple testing. No significant effect was found for either age or gender.

Table 1.

SNPs information

| SNP | Gene Symbol | Protein | Gene location | Chr. | Positiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs486179 | ADRA1A | Adrenergic receptor, alpha 1A | 5' near genee | 8 | 26779851 |

| rs3759292 | AVPR1A | Arginine vasopressin 1A receptor | 5' near genef | 12 | 61833580 |

| rs971074 | ADH7 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 7 | Exon 6 (R230) | 4 | 100560884 |

| rs2350780 | CHRM2 | Cholinergic receptor, muscarinic 2 | IVS3+38804 | 7 | 136243509 |

| rs2289948 | DBI | Diazepam binding inhibitor | 3' near gened | 2 | 119846668 |

| rs12613135 | DBI | Diazepam binding inhibitor | IVS1+1672 | 2 | 119838810 |

| rs5326 | DRD1 | Dopamine D(1) receptor | 5' UTRb | 5 | 174802802 |

| rs7165224 | GABRB3 | GABA-A receptor subunit beta 3 | 5' near genec | 5 | 24575429 |

| rs2058725 | GAD1 | Glutamic acid decarboxylase1 | IVS5+2419 | 2 | 171398367 |

| rs8190646 | GAD2 | Glutamic acid decarboxylase 2 | IVS7+1801 | 10 | 26560513 |

| rs1650420 | GRIN2A | Glutamate receptor 2A | IVS3+5525 | 16 | 10175831 |

| rs4587976 | GRIN2A | Glutamate receptor 2A | IVS3+17720 | 16 | 10163636 |

| rs6497730 | GRIN2A | Glutamate receptor 2A | IVS3+28185 | 16 | 10153171 |

| rs1070487 | GRIN2A | Glutamate receptor 2A | IVS3+37863 | 16 | 10143493 |

| rs1176724 | HTR3A | Serotonin receptor 3A | IVS1-693 | 11 | 113353010 |

| rs897687 | HTR3A | Serotonin receptor 3A | IVS5-926 | 1 | 113361021 |

| rs731780 | SLC29A1 | Solute carrier family 29 member 1 | IVS1-1294 | 6 | 44301684 |

Abbreviations: SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms; Chr, chromosome; TSS, transcription start site; UTR, untranslated region; IVS, intervening sequences. SNPs are sorted by gene symbols.

NCBI Build 36.2.

Exon 2, -94 from the translation initiation site.

-5409 from TSS.

+303 from the stop codon.

-1012 from TSS.

-723 from TSS.

Table 2.

The most significant associations of single SNPs with heroin addiction

| SNP | Gene Symbol | HWE1 | Allele test |

Genotype test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |||

| rs486179 | ADRA1A | 0.68 | 0.0077 | 1.56 (1.11, 2.18) | 0.0251 |

| rs3759292 | AVPR1A | 1.00 | 0.0083 | 0.16 (0.00, 0.76) | 0.0079 |

| rs971074 | ADH7 | 0.18 | 0.0035 | 1.94 (1.22, 3.14) | 0.0011 |

| rs2350780 | CHRM2 | 1.00 | 0.0066 | 1.61 (1.13, 2.30) | 0.0205 |

| rs2289948 | DBI | 0.66 | 0.0053 | 1.86 (1.18, 3.00) | 0.0156 |

| rs12613135 | DBI | 0.25 | 0.0077 | 1.54 (1.11, 2.13) | 0.0181 |

| rs5326 | DRD1 | 1.00 | 0.0029 | 1.94 (1.23, 3.12) | 0.0108 |

| rs7165224 | GABRB3 | 1.00 | 0.0057 | 1.64 (1.14, 2.36) | 0.0090 |

| rs2058725 | GAD1 | 0.03 | 0.0074 | 0.66 (0.47, 0.90) | 0.0050 |

| rs8190646 | GAD2 | 0.41 | 0.0066 | 1.81 (1.16, 2.87) | 0.0363 |

| rs1650420 | GRIN2A | 0.53 | 0.0006 | 1.68 (1.24, 2.27) | 0.0009 |

| rs4587976 | GRIN2A | 0.22 | 0.0039 | 1.56 (1.14, 2.14) | 0.0090 |

| rs6497730 | GRIN2A | 0.01 | 0.0015 | 0.62 (0.45, 0.84) | 0.0025 |

| rs1070487 | GRIN2A | 0.28 | 0.0022 | 1.58 (1.17, 2.15) | 0.0046 |

| rs1176724 | HTR3A | 1.00 | 0.0048 | 0.64 (0.47, 0.88) | 0.0170 |

| rs897687 | HTR3A | 1.00 | 0.0075 | 0.65 (0.47, 0.90) | 0.0265 |

| rs731780 | SLC29A1 | 0.47 | 0.0006 | 0.38 (0.21, 0.69) | 0.0004 |

SNPs are sorted by gene symbols.

Uncorrected Exact test values for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg Proportions in the control sample.

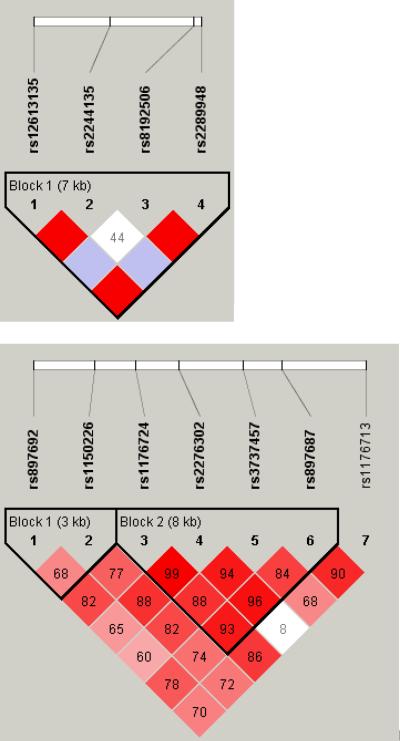

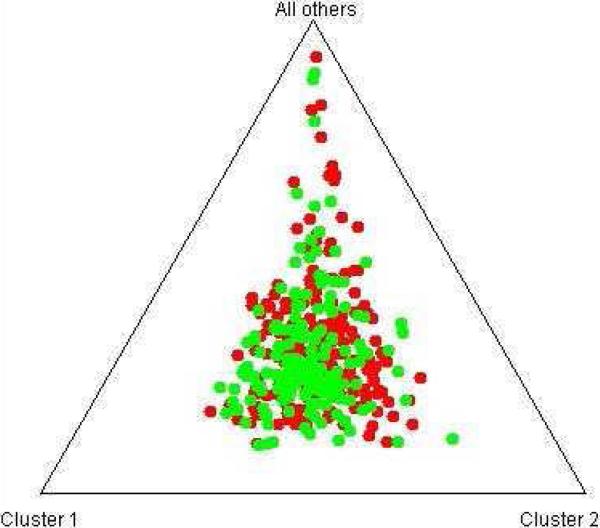

Haplotypes were inferred from LD blocks, which include at least one SNP from the list of top signals on the single SNP analyses. Nominally significant (P < 0.008) association tests for haplotypes are listed in Table 3 and the relevant LD maps are shown in Fig. 1. Association was suggested for haplotypes of GRIN2A, GAD1, HTR3A, DRD1, ADH7 and DBI.

Table 3.

Haplotype association tests

| SNPs | Gene | Haplotype | P-value | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4587976-rs1071502-rs1366076 | GRIN2A | GAT | 0.000096 | protective |

| rs4587976-rs1071502-rs1366076 | GRIN2A | CAT | 0.0036 | risk |

| rs2241164-rs2058725-rs701492-rs3791850-rs7578661 | GAD1 | AGGGG | 0.00063 | protective |

| rs686-rs5326 | DRD1 | AA | 0.0021 | risk |

| rs1154460-rs971074-rs1154470 | ADH7 | AAG | 0.0029 | risk |

| rs1176724-rs2276302-rs3737457-rs897687 | HTR3A | TGGGa | 0.0055 | protective |

| rs12613135-rs2244135-rs8192506-rs2289948 | DBI | GGAGa | 0.0077 | risk |

Figure 1.

LD maps of six genes in AA controls.

The pair-wise correlation between SNPs was measured as D' and is shown (×100) in each box. The color scheme indicates the magnitude of D'. Dark red indicated D'>0.80 with D'=1.0 when no number is given. Haplotypes were generated using block definitions of the solid spine of LD (a-b) and Gabriel (c-f), and haplotype blocks are marked. (a) DBI (b) HTR3A (c) GAD1 (d) DRD1 (e) GRIN2A (f) ADH7.

GRIN2A

Four GRIN2A variants (rs1070487, rs6497730, rs4587976, and rs1650420), all located at a 32 kb area of intron 3 (5' to the translation site at exon 3), accounted for some of the strongest signals in the association test (P = 0.0006-0.0039, Tables 1 and 2). Two additional SNPS from the same block (rs1071502 and rs1366076) gave nominal significant P values for association (P < 0.05) but did not pass the threshold value. Eleven additional GRIN2A SNPs gave negative results. The LD map and haplotype block structure of this region are shown on Fig. 1e; SNPs rs1070487 and rs6497730, are in strong LD (D' = 0.88). SNP rs4587976 forms a 7 kb block with SNPs rs1071502 and rs1366076. SNP rs1650420 is in complete LD (D' = 1) with rs1366076 but is not part of a block, under this block definitions. Haplotype analysis of block 1 (rs4587976-rs1071502-rs1366076) revealed significant association of haplotypes GAT (protective) and CAT (risk), (uncorrected P =9.6E-05 and 0.0036, respectively, Table 3). The association test of the GAT haplotype was close to significance after correction for multiple testing (P = 0.058). The contributing SNP to this effect is rs4587976 (C as a risk allele, G as a protective allele) in concordance with the single SNP analysis. Multi-locus genotype pattern analysis of this block revealed a significant difference between cases and controls with a similar effect, uncorrected P = 0.0005, data not shown).

These four SNPs (rs1650420, rs6497730, rs4587976 and rs1070487) are common in both AA and EA (MAF > 0.33, Table 4), but the minor allele frequencies differ between these ethnic groups. The four SNPs are more common in EA and the difference in allele frequency of rs1650420 is significant after correction for multiple testing (P = 3.5E-06, Table 4). The minor alleles of SNPs rs1650420, rs1070487 and rs6497730 in AA are the major alleles in EA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Differences in allele frequencies between African American and European American controls

| SNP | Gene | Alleles | MAF |

P valuea | HapMap MAF |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | EAb | YRIc | CEUd | ||||

| AA study | |||||||

| rs486179 | ADRA1A | A/G | 0.25 | 0.04 | 2.5E-17 | 0.36 | 0.03 |

| rs3759292 | AVPR1A | G/A | 0.03 | 0.01 | ns | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| rs971074 | ADH7 | A/G | 0.10 | 0.15 | 2.3E-02 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| rs2350780 | CHRM2 | G/A | 0.21 | 0.36 | 1.3E-05 | 0.29 | 0.37 |

| rs2289948 | DBI | G/C | 0.10 | 0.16 | 1.9E-02 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| rs12613135 | DBI | G/A | 0.29 | 0.27 | ns | 0.32 | 0.33 |

| rs5326 | DRD1 | A/G | 0.10 | 0.13 | ns | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| rs7165224 | GABRB3 | A/G | 0.19 | 0.06 | 7.0E-08 | 0.27 | 0.03 |

| rs2058725 | GAD1 | G/A | 0.39 | 0.27 | 9.5E-04 | 0.31 | 0.19 |

| rs8190646 | GAD2 | G/A | 0.11 | 0.08 | ns | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| rs1650420 | GRIN2A | G/A | 0.45 | 0.62e | 3.5E-06 | 0.48 | 0.72e |

| rs4587976 | GRIN2A | C/G | 0.33 | 0.43 | 6.5E-03 | 0.36 | 0.41 |

| rs6497730 | GRIN2A | G/A | 0.47 | 0.59e | 1.4E-03 | 0.30 | 0.59e |

| rs1070487 | GRIN2A | A/G | 0.49 | 0.60e | 2.2E-02 | 0.37 | 0.59e |

| rs1176724 | HTR3A | T/A | 0.39 | 0.02 | 4.9E-41 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| rs897687 | HTR3A | G/A | 0.39 | 0.02 | 2.0E-40 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| rs731780 | SLC29A1 | C/G | 0.12 | 0.00 | 7.9E-13 | 0.06 | 0 |

| EA study b | |||||||

| rs1534891 | CSNK1E | A/G | 0.03 | 0.20 | 1.1E-12 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| rs694066 | GAL | A/G | 0.32 | 0.06 | 1.7E-18 | 0.32 | 0.06 |

| rs3758987 | HTR3B | G/A | 0.41 | 0.23 | 6.2E-07 | 0.47 | 0.23 |

| rs2236861 | OPRD1 | A/G | 0.10 | 0.20 | 3.1E-0.4 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| rs2236857 | OPRD1 | G/A | 0.34 | 0.25 | 1.2E-02 | 0.35 | 0.23 |

| rs3766951 | OPRD1 | G/A | 0.38 | 0.30 | 3.1E-02 | 0.43 | 0.31 |

| rs3778151 | OPRM1 | G/A | 0.31 | 0.13 | 5.6E-09 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| rs6473797 | OPRK1 | A/G | 0.35 | 0.66e | 1.8E-16 | 0.30 | 0.82e |

| rs510769 | OPRM1 | A/G | 0.23 | 0.21 | ns | 0.22 | 0.23 |

Abbreviations: MAF, minor allele frequency. AA, African American, EA, European American. ns, not significant (uncorrected p >0.05). SNPs are listed in the order of P values in each study.

Fisher exact test uncorrected P value.).

Population from Yoruba, Nigeria.

Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry

In this case, the minor allele in AA is the major allele in EA. Numbers in bold are significant after correction for multiple testing (P <4.5E-5).

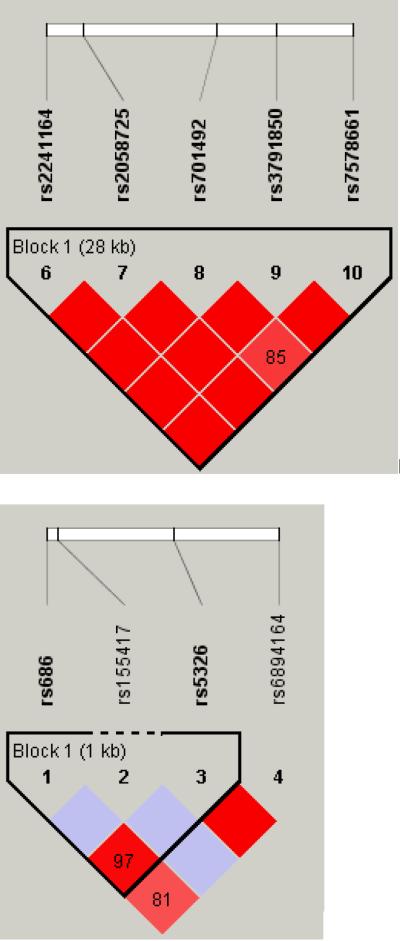

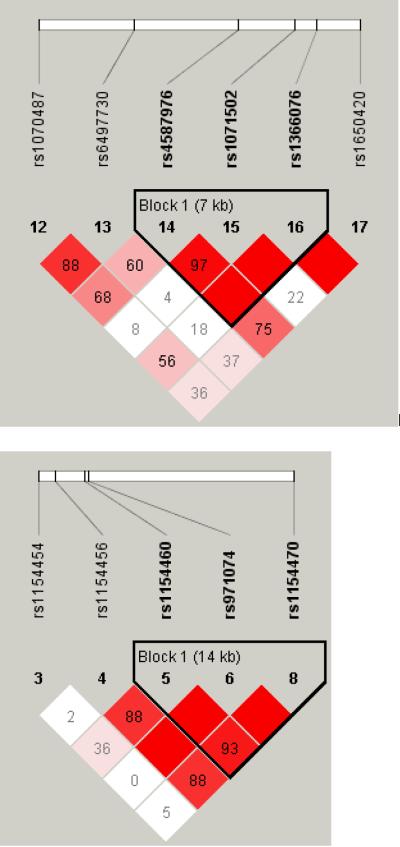

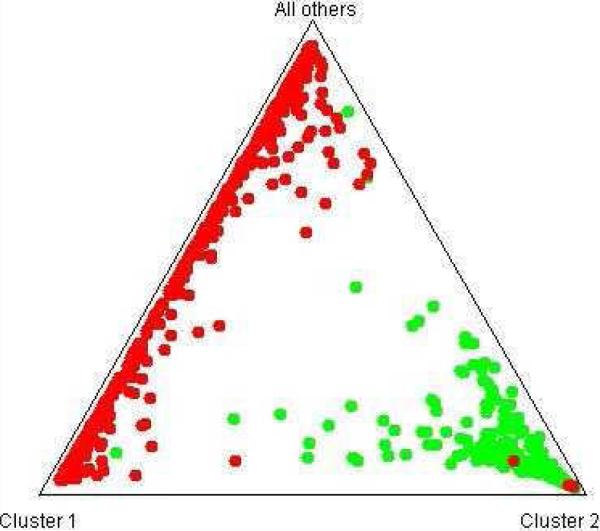

Population Stratification analysis

STRUCTURE analysis using 174 AIMs with adequate quality excluded population stratification between cases and controls in this study (Fig. 2). It also shows clear distinction between the AA sample and the EA sample in our recent (Levran et al., 2008) (Fig. 3). The average extent of admixture (European ancestry proportion) in this AA sample population is 11%. Five AA individuals showed higher than expected EA admixture (0.64-0.84) and the analyses were repeated without them with no significant change in the results.

Figure 2.

STRUCTURE analysis of AA cases (red) vs. controls (green) using 174 AIMs

Figure 3.

STRUCTURE analysis of AA cases and controls (green) vs. EA cases and controls (red) using 174 AIMs

Allele frequencies in AA vs. EA

The allele frequencies (in controls) of the 28 SNPs that gave the most significant association with heroin addiction in the AA population (this study) and the EA population (Levran et al. 2008) are listed in Table 4. Significant differences, after correction for multiple testing (uncorrected P < 4.5E-05), between the two populations were observed for 12 SNPs. These include five SNPs in the EA study and seven SNPs in this study. Six additional SNPs, indicated in the current study, have point-wise significant difference in allele frequencies between the two populations (4.5E-05 < P < 2.3E-02). Four SNPs in this study and one SNP in the EA study have non significant differences in allele frequencies (Table 4). The allele frequencies of reference populations from HapMap (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI) and Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry (CEU), (The International HapMap Consortium, 2003)) are listed in Table 4 for comparison. There is high similarity between the data from our populations and the HapMap data with an expected difference between the admixed AA population and the YRI population.

Discussion

The goal in this study was to identify gene variations which contribute to vulnerability to develop heroin addiction in African Americans. The most significant results that remained close to significance after correction for multiple testing were obtained for the GRIN2A haplotype. Glutamatergic neurotransmission is the major excitatory system in human brain, and genes encoding glutamate receptors are candidate genes for neuropsychiatric disorders. The action of glutamate is mediated by a few receptor families including the NMDA receptor family that is involved in multiple cognitive processes including memory and learning (Paoletti & Neyton, 2007). NMDA receptor Ca2+ permeable channels are heteromers composed of subunit GRIN1 and one or more of the 4 subunits: GRIN2A-D. Expression of the GRIN2A subunit begins around puberty, and a reduced GRIN2A expression was suggested as a risk factor for schizophrenia (Watanabe et al., 1993). Repeated 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy) administration in rats induces neuroadaptive changes in expressions of glutamatergic NMDA subunits, in regions of the brain regulating reward-related associative learning, cognition, and memory (Kindlundh-Hogberg et al., 2008). Grin2a (Nr2a) knockout mice exhibit retarded discrimination learning (Brigman et al., 2008). Associations were reported for GRIN2A polymorphisms with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, and worse chronic outcome in schizophrenia (Adams et al., 2004, Barnby et al., 2005, Itokawa et al., 2003, Tang et al., 2006, Turic et al., 2004). The biological functions of the GRIN2A SNPs indicated in this study are unknown but the finding is supported by associations with multiple SNPs at the same gene, and by the haplotype analysis that was close to significance after correction for multiple testing.

Although all the associations indicated in this study were not significant after correction for multiple testing and could have occurred by chance, some of them corroborate reported associations with alcohol and drug addiction as well as other related disorders. The DRD1 SNP rs5326, from this study is in strong LD (D' = 0.93) with the functional 3' UTR SNP rs686 that was associated with nicotine dependence in AA sample (Huang et al., 2008). The dopamine receptor D1 mediates many of the reinforcing and dependence producing properties of drugs (Koob, 1992), and DRD1 SNPs were associated with compulsive addictive behaviors, sensation seeking in alcohol dependents, and smoking (Comings et al., 1997, Kim et al., 2007, Limosin et al., 2003). The association of ADH7 SNP rs971074 in this study is in concordance with the results of Luo et al. for substance dependence and personality traits (Luo et al., 2006, 2007a, b) and may be related to the role of ADH enzymes in the development and maintenance of the dopaminergic system (Chambon, 1993). The 5' UTR AVPR1A SNP rs3759292, indicated in this study, is located 179 bp 5' to the microsatellite polymorphisms rs9325177 and rs11283312 that were linked to autism, personality traits and altruism (Knafo et al., 2008, Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2008, Wassink et al., 2004). DBI SNP rs2289948, indicated in this study, is in complete LD with SNP rs8192506 that was associated with alcoholism in Japanese (Waga et al., 2007) and with anxiety disorders with panic attacks in EA (Thoeringer et al., 2007). The second DBI SNP rs12613135, indicated in this study, is located in the same haplotype block with SNPs rs2289948 and rs8192506. The diazepam binding inhibitor may play a role in both physical and psychological dependence on opiates as well as anxiety disorders, as indicated by rat studies (Liu et al., 2005). GAD2 SNP rs2058725, from this study, is in the same haplotype block and in complete LD with SNP rs701492 which was associated with alcoholism in Han Taiwanese (Loh El et al., 2006). Other GAD2 SNPs showed association with alcoholism in EA (Lappalainen et al., 2007). The CHRM2 5' UTR SNP rs2350780, indicated in this study, is in strong LD with SNP rs1455858 that was associated with alcohol dependence, drug dependence and affective disorders in EA and AA (Luo et al., 2005). This gene may be involved in memory, higher cognition and behavioral effects of drugs of abuse.

The candidate gene approach is limited in scope, but this study suggests that testing biological candidate genes in a well-characterized population with a well-defined phenotype may facilitate the identification of genetic variants that are associated with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction and are specific to an ethnic group. This approach is more economical than whole-genome screening and may increase the power of the study due to the smaller number of tests performed. We cannot determine if the negative findings in this study indicate true negative association, because the SNP coverage of some of the genes may be limited and due to the limited power of the study.

Population stratification and admixture are critical problems in case-control association studies. Spurious associations can arise when mixed populations, with different allele frequencies, are used. The AA population is a recently admixed population with estimated mean European ancestry proportion of 17-20% [e.g. (Guthery et al., 2007, Reiner et al., 2005). In contrast, in this study population, there was an average of 11% European ancestry admixture. To minimize the effect of admixture we applied two independent methods and excluded population stratification between cases and controls. The AIMs data also validated the accuracy of the three generations ethnic self-identification in our dataset. The few exceptions (~1%) may be due to the individuals' inaccurate knowledge of their own family histories.

It is intriguing that the SNPs with the lowest P values for association with heroin addiction in the AA populations, in this study, and the EA population in our recent study (Levran et al., 2008), are so distinct. One possible explanation for these findings is the differences in allele frequencies between the two populations that are observed for 18 SNPs out of the total of 26 SNPs indicated in both studies and are supported by the HapMap data. The results for the rest of the SNPs, if their association with heroin addiction is validated, can not be explained by allele frequency differences and may be influenced by other factors such as LD pattern or modifier genes that may be different in these populations.

It was documented that the risk to develop heroin addiction is similar among all ethnic groups. The possibility that the specific gene variants contributing to the vulnerability to develop heroin addiction differ among ethnic groups, is intriguing. This phenomenon was found for Crohn's disease (where the susceptibility CARD15 variants in EA were not present in Japanese), AIDS (where the protective CCR5 variant is common in EA and absent in other ethnic groups), and Alzheimer's disease (where the APOE E4 variant have differential effect between ethnic groups) (Tate & Goldstein, 2004). It points to a public health challenge to provide population-specific, and in the future individual-specific, diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the clinical staff that enrolled and assessed subjects for this study, including Elizabeth Ducat, Brenda Ray, Dorothy Melia and Lisa Borg. We are grateful to D. Goldman and his group from the NIH/NIAAA, for the design of the micro-array; Connie Zhao and Bin Zhang from the Rockefeller Genomic Resource Center, for their excellent assistance in genotyping. We thank Ann Ho, David Nielsen, Vadim Yuferov and Susan Russo for discussion, comments and/or proofreading of the manuscript. We would like to express our profound gratitude to the late K. Steven LaForge for setting the foundation for this study.

References

- Adams J, Crosbie J, Wigg K, Ickowicz A, Pathare T, Roberts W, Malone M, Schachar R, Tannock R, Kennedy JL, Barr CL. Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2A (GRIN2A) gene as a positional candidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the 16p13 region. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:494–499. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnby G, Abbott A, Sykes N, Morris A, Weeks DE, Mott R, Lamb J, Bailey AJ, Monaco AP. Candidate-gene screening and association analysis at the autism-susceptibility locus on chromosome 16p: evidence of association at GRIN2A and ABAT. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:950–966. doi: 10.1086/430454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigman JL, Feyder M, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Mishina M, Holmes A. Impaired discrimination learning in mice lacking the NMDA receptor NR2A subunit. Learn Mem. 2008;15:50–54. doi: 10.1101/lm.777308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon P. The molecular and genetic dissection of the retinoid signalling pathway. Gene. 1993;135:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90069-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CY, Hong CJ, Yu YW, Chen TJ, Wu HC, Tsai SJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Val66Met) genetic polymorphism is associated with substance abuse in males. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;140:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Gade R, Wu S, Chiu C, Dietz G, Muhleman D, Saucier G, Ferry L, Rosenthal RJ, Lesieur HR, Rugle LJ, MacMurray P. Studies of the potential role of the dopamine D1 receptor gene in addictive behaviors. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:44–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Roeder K, Wasserman L. Genomic control, a new approach to genetic-based association studies. Theor Popul Biol. 2001;60:155–166. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2001.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Shen PH, Xu K, Hodgkinson C, Goldman D. Using ancestry-informative markers to define populations and detect population stratification. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:19–26. doi: 10.1177/1359786806066041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu-Cordero SN, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthery SL, Salisbury BA, Pungliya MS, Stephens JC, Bamshad M. The structure of common genetic variation in United States populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1221–1231. doi: 10.1086/522239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Xu K, Shen PH, Heinz E, Lobos EA, Binder EB, Cubells J, Ehlers CL, Gelernter J, Mann J, Riley B, Roy A, Tabakoff B, Todd RD, Zhou Z, Goldman D. Addictions biology: haplotype-based analysis for 130 candidate genes on a single array. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:505–515. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Beuten J, Dupont RT, Li MD. Significant association of DRD1 with nicotine dependence. Hum Genet. 2008;123:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itokawa M, Yamada K, Yoshitsugu K, Toyota T, Suga T, Ohba H, Watanabe A, Hattori E, Shimizu H, Kumakura T, Ebihara M, Meerabux JM, Toru M, Yoshikawa T. A microsatellite repeat in the promoter of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2A subunit (GRIN2A) gene suppresses transcriptional activity and correlates with chronic outcome in schizophrenia. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:271–278. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg SH, McHugh PF, Bell K, Schluger JH, Schluger RP, LaForge KS, Ho A, Kreek MJ. The Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellogg scale: a new, rapid method for quantifying substance abuse and its possible applications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:137–150. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DJ, Park BL, Yoon S, Lee HK, Joe KH, Cheon YH, Gwon DH, Cho SN, Lee HW, NamGung S, Shin HD. 5' UTR polymorphism of dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1) associated with severity and temperament of alcoholism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindlundh-Hogberg AM, Blomqvist A, Malki R, Schioth HB. Extensive neuroadaptive changes in cortical gene-transcript expressions of the glutamate system in response to repeated intermittent MDMA administration in adolescent rats. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafo A, Israel S, Darvasi A, Bachner-Melman R, Uzefovsky F, Cohen L, Feldman E, Lerer E, Laiba E, Raz Y, Nemanov L, Gritsenko I, Dina C, Agam G, Dean B, Bornstein G, Ebstein RP. Individual differences in allocation of funds in the dictator game associated with length of the arginine vasopressin 1a receptor RS3 promoter region and correlation between RS3 length and hippocampal mRNA. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:266–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, LaForge KS. Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nn1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen J, Krupitsky E, Kranzler HR, Luo X, Remizov M, Pchelina S, Taraskina A, Zvartau E, Rasanen P, Makikyro T, Somberg LK, Krystal JH, Stein MB, Gelernter J. Mutation screen of the GAD2 gene and association study of alcoholism in three populations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:183–192. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levran O, Londono D, O'Hara K, Nielsen DA, Peles E, Rotrosen J, Casadonte P, Linzy S, Randesi M, Ott J, Adelson M, Kreek MJ. Genetic susceptibility to heroin addiction; a candidate-gene association study. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:720–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limosin F, Loze JY, Rouillon F, Ades J, Gorwood P. Association between dopamine receptor D1 gene DdeI polymorphism and sensation seeking in alcohol-dependent men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1226–1228. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000081624.57507.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li Y, Zhou L, Chen H, Su Z, Hao W. Conditioned place preference associates with the mRNA expression of diazepam binding inhibitor in brain regions of the addicted rat during withdrawal. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;137:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh el W, Lane HY, Chen CH, Chang PS, Ku LW, Wang KH, Cheng AT. Glutamate decarboxylase genes and alcoholism in Han Taiwanese men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1817–1823. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh EW, Tang NL, Lee DT, Liu SI, Stadlin A. Association analysis of GABA receptor subunit genes on 5q33 with heroin dependence in a Chinese male population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:439–443. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmueller KE, Mauney MM, Reich D, Braverman JM. Variants associated with common disease are not unusually differentiated in frequency across populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:130–136. doi: 10.1086/499287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Wang S, Blumberg HP, Gelernter J. CHRM2 gene predisposes to alcohol dependence, drug dependence and affective disorders: results from an extended case-control structured association study. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2421–2434. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Wang S, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Diplotype trend regression analysis of the ADH gene cluster and the ALDH2 gene: multiple significant associations with alcohol dependence. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:973–987. doi: 10.1086/504113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Wang S, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Multiple ADH genes modulate risk for drug dependence in both African-and European-Americans. Hum Mol Genet. 2007a;16:380–390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Zhang H, Wang S, Gelernter J. ADH7 variation modulates extraversion and conscientiousness in substance-dependent subjects. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007b;147B:179–186. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kolachana B, Gold B, Olsh A, Nicodemus KK, Mattay V, Dean M, Weinberger DR. Genetic variants in AVPR1A linked to autism predict amygdala activation and personality traits in healthy humans. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.54. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen DA, Barral S, Proudnikov D, Kellogg S, Ho A, Ott J, Kreek MJ. TPH2 and TPH1: association of variants and interactions with heroin addiction. Behav Genet. 2008;38:133–150. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Neyton J. NMDA receptor subunits: function and pharmacology. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudnikov D, Hamon S, Ott J, Kreek MJ. Association of polymorphisms in the melanocortin receptor type 2 (MC2R, ACTH receptor) gene with heroin addiction. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudnikov D, LaForge KS, Hofflich H, Levenstien M, Gordon D, Barral S, Ott J, Kreek MJ. Association analysis of polymorphisms in serotonin 1B receptor (HTR1B) gene with heroin addiction: a comparison of molecular and statistically estimated haplotypes. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:25–36. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000182782.87932.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner AP, Ziv E, Lind DL, Nievergelt CM, Schork NJ, Cummings SR, Phong A, Burchard EG, Harris TB, Psaty BM, Kwok PY. Population structure, admixture, and aging-related phenotypes in African American adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:463–477. doi: 10.1086/428654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD. The positive false discovery rate: a Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Ann. Statist. 2003;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi A, Boor K, Szekely A, Gaszner P, Kalasz H, Sasvari-Szekely M, Barta C. Combined effect of promoter polymorphisms in the dopamine D4 receptor and the serotonin transporter genes in heroin dependence. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2005;7:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Chen X, Xu X, Wu R, Zhao J, Hu Z, Xia K. Significant linkage and association between a functional (GT)n polymorphism in promoter of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit gene (GRIN2A) and schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2006;409:80–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate SK, Goldstein DB. Will tomorrow's medicines work for everyone? Nat Genet. 2004;36:S34–42. doi: 10.1038/ng1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International HapMap Consortium The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoeringer CK, Binder EB, Salyakina D, Erhardt A, Ising M, Unschuld PG, Kern N, Lucae S, Brueckl TM, Mueller MB, Fuchs B, Puetz B, Lieb R, Uhr M, Holsboer F, Mueller-Myhsok B, Keck ME. Association of a Met88Val diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI) gene polymorphism and anxiety disorders with panic attacks. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Lin N, Meyer JM, Toomey R, Faraone SV, Eaves L. Genetic influences on DSM-III-R drug abuse and dependence: a study of 3,372 twin pairs. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:473–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<473::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turic D, Langley K, Mills S, Stephens M, Lawson D, Govan C, Williams N, Van Den Bree M, Craddock N, Kent L, Owen M, O'Donovan M, Thapar A. Follow-up of genetic linkage findings on chromosome 16p13: evidence of association of N-methyl-D aspartate glutamate receptor 2A gene polymorphism with ADHD. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:169–173. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waga C, Ikeda K, Iwahashi K. The relationship between alcoholism and DBI gene polymorphism in Japanese--genotyping of the +529A/T in DBI gene polymorphism based on PCR. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2007;42:629–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassink TH, Piven J, Vieland VJ, Pietila J, Goedken RJ, Folstein SE, Sheffield VC. Examination of AVPR1a as an autism susceptibility gene. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:968–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Sakimura K, Mishina M. Distinct spatio-temporal distributions of the NMDA receptor channel subunit mRNAs in the brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;707:463–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb38099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Lichtermann D, Lipsky RH, Franke P, Liu X, Hu Y, Cao L, Schwab SG, Wildenauer DB, Bau CH, Ferro E, Astor W, Finch T, Terry J, Taubman J, Maier W, Goldman D. Association of specific haplotypes of D2 dopamine receptor gene with vulnerability to heroin dependence in 2 distinct populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:597–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Liao G, Liu Y, Wang Y, Yang Z, Lin Y, Shen Y, Li S, Xiao J, Guo H, Wan C, Wang Z. Association of the 54-nucleotide repeat polymorphism of hPer3 with heroin dependence in Han Chinese population. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;7:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo L, Kranzler HR, Luo X, Covault J, Gelernter J. CNR1 Variation Modulates Risk for Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]