Abstract

Background

Individual and contextual factors jointly participate in the onset and progression of substance abuse; however, the pattern of their relationship in males and females has not been systematically studied.

Objectives

Male and female children and adolescents were compared to determine the relative influence of individual susceptibility (neurobehavior disinhibition or ND) and social environment (deviancy in peers) on use of illegal drugs.

Methods

Boys (N = 380) and girls (N = 127) were prospectively tracked from age 10–12 to age 16 to delineate the role of ND and peer deviancy on use of illegal drugs.

Results

Girls exhibited lower ND scores than boys in childhood and were less inclined to affiliate with deviant peers. These differences were reduced or disappeared by mid-adolescence. In boys only, peer deviancy in childhood mediated the association between ND and illegal drug use at age 16. In both genders, peer deviancy in mid-adolescence mediated ND and substance abuse at age 16.

Conclusions

Individual and contextual risk factors promoting substance abuse are more salient at a younger age in boys compared to girls.

Scientific Significance

These results point to the need for earlier screening and intervention for boys.

Keywords: Adolescence, gender, illegal drug involvement, neurobehavior disinhibition, peer deviancy

INTRODUCTION

Results obtained from epidemiological investigations indicate that males have more opportunity to use cannabis than females (1, 2). Controlling for differential experience, consumption rates are however not different between genders (2). Nevertheless, the risk of qualifying for diagnosis of cannabis dependence within the first two years after cannabis exposure climbs to 4% in males while remaining constant at 1% in females (3).

To date, the factors besides differences in opportunity for cannabis consumption that could account for this discrepancy in the risk for cannabis dependence between genders has not been studied. Whereas many aspects of the environment, spanning family, school, social network, and neighborhood are likely contributory influences, it is widely recognized that exposure to socially deviant peers during adolescence is an especially salient factor (4–8). Significantly, it has been reported that deviant peers have a stronger adverse impact in girls (5).

Individual differences in psychological characteristics that are known to predispose to substance abuse may also account for the lower prevalence in females. Notably, boys have a higher prevalence of conduct disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder than girls (9). These externalizing disorders in childhood have been frequently shown to presage substance consumption and diagnosis of substance use disorder (SUD) (10). From the perspective of quantitative traits, the score on a construct termed neurobehavior disinhibition (ND) distinguishes 10–12 year old boys who are at high and low risk for SUD based on parental history, and is a significant predictor of SUD manifest by young adulthood (11–14). The observation that ND score in 10–12 year old boys also predicts marijuana use (15), social maladjustment (16), and low motivation to desist drug use following brief intervention in mid-adolescence (17) additionally illustrates that this trait captures an important facet of the liability for substance use and subsequently SUD diagnosis. Inasmuch as girls have lower prevalence of externalizing disorders than boys, it is plausible to theorize that severity of disinhibitory behavior may contribute to the gender difference in substance use prevalence.

Research has not yet been conducted which compares the relation between individual susceptibility (ND) and social environment (peer deviancy) in males and females on the emergence of substance abuse between childhood and adolescence. Notably, undercontrolled behavior is more common in males (9) whereas affiliation with deviant peers appears to have greater negative impact in females (5). Thus, covariation between individual and contextual influences on substance abuse risk may differ between genders, thereby accounting for the lower prevalence of substance use in girls.

Many studies have shown that friendships form according to commonality of characteristics among the members (18–20). Because boys are more psychologically dysregulated than girls, there is thus greater likelihood of affiliating with socially deviant peers and harboring attitudes tolerant of deviant behavior (15). Many studies have documented these latter characteristics in substance abusers. Hence, better self-regulation in girls, mediated by less peer deviancy, may account for the lower prevalence of substance abuse. Complicating the picture, however, is the finding that girls are more sensitive to the quality of their interpersonal relationships and therefore more likely than boys to experience an adverse impact from risk-promoting friendships. In effect, whereas girls appear to have lower severity than boys on individual and contextual factors promoting risk for substance abuse, the pattern of relationship among these factors may also not be the same between genders. To address this issue, the present study compared boys and girls on the pattern of association between individual susceptibility (ND) and social environment (deviant peers) leading to involvement with illegal drugs during the critical period between late childhood (age 10–12) and mid-adolescence (age 16).

METHODS

Subjects

Enrollment of boys (N = 380) and girls (N = 127) was conducted when they were between 10–12 years of age. At age 16, a follow-up evaluation was conducted along with an evaluation of substance use behavior. Recruitment of the participants was conducted through their fathers (probands) who qualified for a DSM-III-R lifetime SUD diagnosis consequent to use of an illegal compound or had no axis I or axis II adult psychiatric disorder. DSM-III-R criteria were utilized because this project was initiated prior to publication of the DSM-IV. Lifetime diagnosis was determined using an expanded version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (21). The men with SUD were recruited using a variety of methods, including public service announcements, advertisement, and a market research firm that conducted random digit dialing. Approximately 25% of the sample was accrued from treatment facilities. Men without SUD were recruited using the same procedures except that none were obtained from treatment facilities. As shown in Table 1, the boys and girls were similar in age, grade in school, socioeconomic status (SES), and rate of parental SUD. The sample of boys had 13% more European Americans than females (p = .005), accordingly this factor was controlled in the statistical analyses. Children with lifetime history of psychosis, chronic physical disability, neurological disease, uncorrectable sensory handicap, full scale IQ below 80 on the WISC-III-R, and signs of fetal alcohol injury determined upon physical examination conducted by a trained registered nurse were excluded from study.

TABLE 1.

Personal and demographic characteristics of the sample

| Boys (n = 380) | Girls (n = 127) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | p-value | |

| Age | 11.41 (.9) | 11.45 (.9) | .38 | .53 |

| Education (grade) | 4.57 (1.1) | 4.71 (1.1) | 1.88 | .17 |

| SES | 41.29 (14.19) % |

41.29 (16.17) % |

<.01 | .99 |

| Paternal SUD | 47.1 | 38.6 | χ2 = 2.79 | .09 |

| Maternal SUD | 22.9 | 22.8 | χ2 < .01 | .99 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| European American | 76.1 | 63.3 | χ2 = 7.89 | .005 |

| African American | 23.9 | 36.7 |

Measures

Neurobehavior Disinhibition (ND) (age 10–12, 16)

This trait consists of indicators measuring affect regulation, behavior control, and executive cognitive capacity. A description of the rationale, item content, and psychometric properties of the ND trait can be found in Mezzich et al. (14). Notably, the ND trait is unidimensional at age 10–12(χ2 = 4.39 [df = 3], p = .21; root mean square error approximation [RMSEA] = .041; standardized root mean square residual (SRMSR) = .037) and age 16 (χ2 = 5.77 [df = 3], p = .12; RMSEA = .050; SRMSR = .037). Cronbach alpha is, respectively, .91 and .90. Because the score on the ND trait has been shown to be is a significant predictor of marijuana use in boys (16), it is heuristic for determining whether it is informative for elucidating gender differences.

Peer Behavior Scale (PBS) (22) (age 10–12 and 16)

Social deviance in peers was assessed by selecting items from several scales according to their face validity. The items and their source are shown in the online version of the manuscript).

Principal component analysis indicated that 9 items, having factor loadings ranging from .36–.80 on the first factor, accounted for 45% of overall variance. Confirmatory factor analysis at age 10–12 verified unidimensionality (χ2 = 18.72 [df = 12], p = .102; RMSEA = .038; comparative fit index [CFI] = .98; Tucker-Lewis Index [TLI] = .98) at age 10–12). Unidimensionality was also documented at age 16 (χ2 = 22.22 [df = 15], p = .10; RMSEA = .030; CFI = .98, TLI =.98). Furthermore, item response theory (IRT) analyses demonstrated that the items have moderate to high discrimination at age 10–12 (M = .72, SD =.24) and age 16: (M = .99, SD =.50). In addition, severity threshold was moderate to high at age 10–12 (M = 2.25, SD = 1.66) and age 16 (M = .83, SD = .60). Internal consistency was .71 at age 10–12 and .80 at age 16.

Consumption of Illicit Drugs (age 16)

Number of illicit drugs used in lifetime was measured using the Drug and Alcohol Use Chart (23). Frequency of illegal drug use in the past month was evaluated using the revised Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI-R) (24).

Procedure

The purpose of the project was explained to the parents and their children upon arrival at the laboratory. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and written assent was obtained from the child prior to implementing the research protocols. In addition, the parents and their children were informed that privacy was protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality issued to CEDAR by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The protocols were administered in fixed order in a private room after the research associate determined that the child was not coerced to participate. Next, the participants were screened for alcohol and drugs using breathalyzer and urinalysis. This ensured that the information obtained was not confounded or biased by the psychoactive effects of drugs. Upon completion of the research protocol, the subjects were financially compensated and discharged from the laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

At the outset, the ND and PBS scores were transformed to a T-scale distribution to enable facile comparisons between genders and across time. Preliminary analyses were conducted using ANCOVA to compare differences between the boys and girls on ND, PBS, and consumption of illegal drugs. Multiple group path analysis was conducted next to elucidate the pattern and strength of relationship between ND, PBS, and involvement with illegal drugs in the boys and girls. Regression coefficients in the model were estimated using Mplus (25). Mplus uses the weighted least square parameter estimation method with diagonal weight matrix with robust standard errors. Four indices of model fit were used: the χ2 goodness-of-fit index, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI. A non-significant χ2 value (p ≥ .05) indicates that the data are consistent with the model. RMSEA values of greater than .08 reflect a poor fit, values of .05 to .08 indicate an acceptable fit, and values of less than .05 reflect a good fit (26). For the CFI and TLI, values greater than .90 and .95 are required for good model fit (27, 28).

Mediated paths were tested using the method described by Sobel (29) using the formula: , where b1 is the regression coefficient between predictor and mediator, b2 is the regression coefficient between mediator and dependent variable, and σ2 is the square of the estimate of the standard error of the corresponding regression coefficient. Because of sample size limitations, all of the variables used in the path analysis were manifest variables. Frequency of illegal drug use and number of illegal drugs tried had skewed distributions; hence, a logarithmic transformation was performed to normalize the distributions. SES and ethnicity were included into a multiple-group path analysis because both demographic variables were significantly correlated with outcome variables.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents the results of comparisons between the boys and girls on the ND and PBS measures as well as involvement with illegal drugs. The boys reported consuming more illegal drugs (F = 6.96, p = .009) and more frequently (F = 8.885, p = .003) than girls at age 16. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a gender and time of assessment interaction (F = 5.31, [dfs = 1, 490], p = .02) on the ND trait. ND score in the boys was stable across the two timepoints (t = 1.55, df = 379, p = .121) while the girls exhibited an increase in ND severity between ages 10–12 and 16 (t = −4.10, df = 126, p < .001). The results of ANOVA on the PBS revealed that boys scored significantly higher at both ages 10−12 and 16. A gender × time of assessment interaction was not observed (F = .49, [dfs = 1, 490], p = .49). Boys (t = −.15, df = 379, p = .88) and girls (t = −.31, df = 126, p = .76) respectively did not show a change in PBS scores between 10–12 years and 16 years of age.

TABLE 2.

Comparisons between boys and girls on predictor and outcome variables

| Boys (n = 380) | Girls (n = 127) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | p-value | |

| Neurobehavior disinhibition (age 10–12)1 | 52.97 (11.13) | 47.43 (8.45) | 40.56 | <.001 |

| Neurobehavior disinhibition (age 16)1 | 50.51 (10.17) | 48.88 (9.72) | 2.51 | .114 |

| Peer behavior scale (age 10–12)1 | 50.85 (9.87) | 47.56 (10.02) | 14.90 | <.001 |

| Peer behavior scale (age 16)1 | 50.60 (10.26) | 48.30 (9.10) | 5.52 | .019 |

| Frequency of illegal drug use (age 16) | .60 (1.32) | .24 (.64) | 8.85 | .003 |

| Number of illegal drugs tried (age 16) | .58 (1.27) | .28 (.48) | 6.96 | .009 |

Transformed to T-scale distribution.

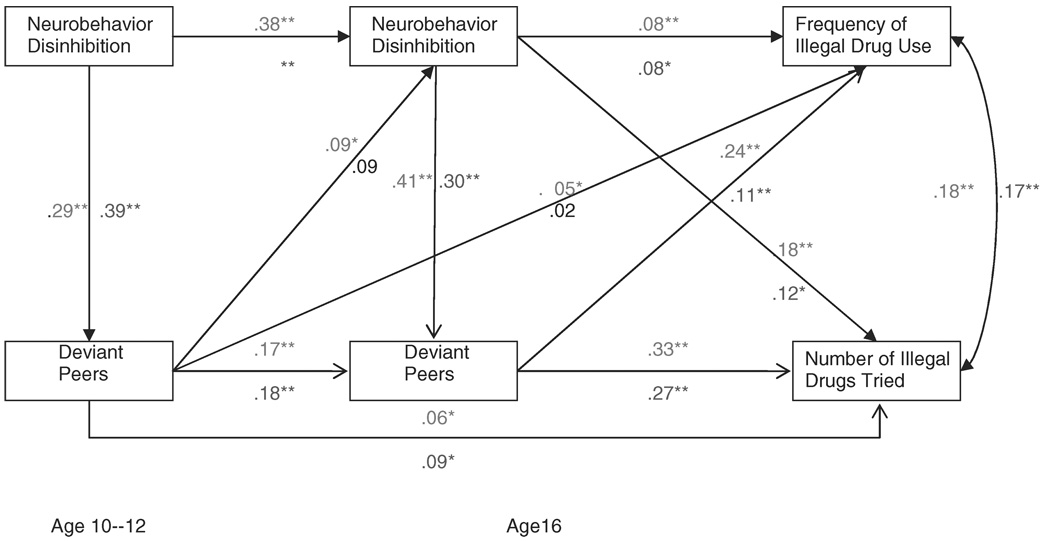

Figure 1 depicts the results of the path analysis for the boys and girls. Unstandardized regression estimates for the boys and girls are depicted on the top and bottom of the arrows. An acceptable model-data fit was obtained (chi-square = 7.66, df = 6, p = .26, RMSEA = .029, CFI = .99, and TLI = .99) controlling for ethnicity and SES.

FIG. 1.

Association between neurobehavior disinhibition and peer deviancy on use of illegal drugs. (Regression coefficients above and below the path arrows respectively pertain to boys and girls.)

The direct paths reveal similar results in boys and girls. ND score at age 10–12 predicts PBS score at age 10–12 in boys (β = .29, t = 6.95, p < .01) and girls (β = .39, t = 5.12, p < .01). ND at age 10–12 predicts ND at age 16 in boys (β = .38, t = 10.41, p < .01) and girls (β = .36, t = 6.27, p < .01) which in turn predicts number of illegal drugs ever used in boys (β = .18, t = 5.49, p < .01) and girls (β = .12, t = 2.05, p < .05) and frequency of illegal drug use in boys (β = .08, t = 3.39, p < .01) and girls (β = .08, t = 2.46, p < .05). ND at age 16 predicts PBS score at age 16 in boys (β = .41, t = 8.64, p < .01) and girls (β = .30, t = 3.63, p < .01), which in turn predicts frequency of illegal drug use in boys (β = .24, t = 11.12, p < .01) and girls (β = .11, t = 4.06, p < .01) and number of illegal drugs ever tried in boys (β = .33, t = 11.16, p < .01) and girls (β = .27, t = 5.21, p < .01). PBS score at age 10–12 predicts number of illegal drugs ever used in boys (β = .06, t = 2.31, p < .05) and girls (β = .09, t = 2.20, p < .05). PBS score at age 16 also predicted number of illegal drugs ever used at age 16 in boys (β = .17, t = 4.40, p < .01) and girls (β = .18, t = 3.03, p < .01).

Differences were observed, however, between the genders with respect to PBS score at age 10–12. At this age, PBS score predicted ND at age 16 in boys (β = .09, t = 2.43, p < .05), but not in girls (β = .09, t = 1.77, p = ns). Furthermore, PBS score at age 10–12 predicted frequency of illegal drug use in boys (β = .05, t = 2.62, p < .05), but not in girls (β = .02, t = .87, p = ns).

PBS score at age 16 mediated the association between ND at age 16 and number of illegal drugs used in boys (β = .15, t = 6.83, p < .01) and girls (β = .09, t = 2.29, p < .05). In addition, PBS score at age 16 mediated the association between ND at age 16 and frequency of illegal drug use in boys (β = .18, t = 6.82, p < .01) and girls (β = .09, t = 2.71, p < .05). Furthermore, PBS score at age 10–12 mediated the association between ND at age 10–12 and PBS score at age 16 in boys (β = .06, t = 3.72, p < .01) and girls (β = .08, t = 2.61, p < .05). However, in boys only, PBS score mediated the association of ND at age 10–12 and number of illegal drugs ever used (β =.02, t = 2.20, p < .05) and frequency of illegal drug use (β = .03, t = 2.45, p < .05). Also, in boys only, ND at age 16 mediated the association of PBS score at age 10–12 and number of illegal drugs used at age 16 (β = .02, t = 2.24, p < .05).

DISCUSSION

To briefly recapitulate the results, girls exhibit better psychological self-dysregulation than boys as measured by the ND trait at age 10–12 but are not different by mid-adolescence. The amelioration of this difference is due to an increment in ND severity in the girls. In addition, girls are less inclined to affiliate with deviant peers in late childhood and mid-adolescence and report less involvement with illegal drugs.

In mid-adolescence, the pattern of relation between psychological dysregulation and affiliation with deviant peers leading to use of illegal drugs is essentially the same in boys and girls. ND predicts affiliation with deviant peers that in turn predicts consumption of illegal drugs. Peer deviancy at age 16 mediates the association between ND at age 10–12 and use of illegal drugs in both boys and girls, suggesting that high ND during adolescence biases the individual to select deviant peers. A gender difference is noted, however, regarding the role of deviant peers in childhood. Peer deviancy in 10–12 year old boys but not girls mediates the association between ND at age 10–12 and illegal drug use at age 16. Notably, girls tend to become involved in antisocial behavior during adolescence at which time they display the same problems as boys whose antisocial behavior emerged during childhood (30, 31). One possible reason for the later emergence is that parenting is easier because girls have better psychological self-regulation during childhood. However, the increase in psychological dysregulation during adolescence promotes affiliation with deviant peers. In circumstances where sexual maturation has an early onset age, the propensity for deviancy is amplified because the appearance of advanced chronological age increases the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors concomitant to involvement with older boys (32, 33).

The lower prevalence and severity of substance abuse in girls may thus be due, at least in part, to the later age in which ND attains a level of severity that is similar to boys. Specifically, social homophily, whereby dysregulated antisocial youths establish friendships with similar behaving peers (34) has later impact in girls than boys. Inasmuch as peer deviancy mediates the association between ND and substance abuse, it is plausible to conclude that lower ND in girls during childhood reduces the opportunity for initiating illegal drug use. Notably, results of the 2006 Monitoring the Future Survey (35) indicate that 8th grade boys and girls both have 8% prevalence of 30-day use of an illegal drug which by 12th grade, increases respectively to 17.9% and 15.4%. Based on the results obtained in this study, it is concluded that lower ND in girls during childhood lowers the likelihood of affiliation with deviant peers at this young age which ultimately manifests as less severe and lower prevalence of substance abuse.

While the present findings improve understanding of the factors underlying gender differences on the risk for and development of substance abuse, it is possible that the findings are not generalizable to the population since the subjects were recruited through proband fathers. Prior research conducted on a subset of this sample has, however, not revealed evidence of biased sampling (22).

In summary, boys have stronger susceptibility (neurobehavior disinhibition) and score higher than girls on social context (deviant peers) portending consumption of illegal drugs. The pattern of relationship among these variables and substance abuse is the same between genders in mid-adolescence. However, in late childhood, affiliation with deviant peers in boys but not girls mediates the relation between neurobehavior disinhibition and illegal drug use at age 16. These results suggest that the momentum to illegal drug use is stronger and has earlier onset in boys than girls. Considered in aggregate, the findings point to the need for intervention in early childhood in boys. In both genders, insulating dysregulated youths from the opportunity to form friendships with socially deviant peers would appear to be essential for preventing substance abuse.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50 DA05605, K02 DA 017822, and RO1 DA05952).

APPENDIX

| Items Comprising the Peer Behavior Scale (PBS) |

|---|

| Peer Delinquency Scale (36) |

| During the past 6 months, how many of your friends have used alcohol? |

| How many of your friends used marijuana or hashish? |

| Parents and Peers Scale (36) |

| During the past 6 months, were there any children in your group of friends your parents disapproved? |

| Opportunity/Resistance Scale (36) |

| During the past six months, has someone said that you should go drinking with them? |

| Has someone put pressure on you to drink? |

| Conventional Activities of Friends Scale (36) |

| Are your friends good students? |

| Have they obeyed school rules? |

| Child Report on Peer Environment (23) |

| Do you personally know someone who trades or sells drugs? |

| How many of your friends are involved in religious activities? |

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Contributor Information

Levent Kirisci, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Ada C. Mezzich, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Maureen Reynolds, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Ralph E. Tarter, School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Sema Aytaclar, Bakirkoy State Hospital for Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases, Istanbul, Turkey

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Etten ML, Anthony JC. Comparative epidemiology of initial drug opportunities and transition to first use: Marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens and heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Etten ML, Anthony JC. Male-female differences in transition from first drug opportunity to first use: Searching for subgroup variation by age, race, region, and urban status. J Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine. 2001;10:797–804. doi: 10.1089/15246090152636550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Male-female differences in the risk of progression from first use to dependence upon cannabis, cocaine, and alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dishion TJ, Owen LD. A longitudinal analysis of friendships and substance use: bidirectional influence from adolescence to adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:480–491. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gifford-Smith M, Dodge KA, Dision TJ, McCord J. Peer influence in children and adolescents: Crossing the bridge from developmental to intervention science. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2005;33:255–265. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3563-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden AF, Heath AC. Correlates of cannabis initiation in a longitudinal sample of young women: The importance of peer influences. Preventive Medicine. 2007;45:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preston P. Marijuana use as a coping response to psychological strain: Racial, ethnic and gender differences among young adults. Deviant Beh. 2006;27:397–421. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butters JE. The impact of peers and social disapproval on high-risk cannabis use: Gender differences and implications for drug education. Drugs: education, prevention and policy. 2004;11:381–390. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siminoff E, Pickles A, Meyer JM, Silberg JL, Maes HH, Loeber R, et al. The Virginian twin study of adolescent behavioral development: Influences of age, sex, and impairment on rates of disorder. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1997;54:801–808. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarter R, Kirisci L, Ridenour T, Vanyukov M. Prediction of substance use disorder between childhood and adulthood using the internalizing and externalizing scales of the CBCL. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirisci L, Vanyukov M, Tarter RE. Detection of youth at high risk for substance use disorders: A longitudinal study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:243–252. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich AC, Cornelius J, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, Gardner W, Blackson T, Clark DB. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiat. 2003;60:1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Habeych M, Reynolds M, Vanyukov M. Neurobehavior disinhibition in childhood predisposes boys to substance use disorder by young adulthood: Direct and mediated etiological pathways. Drug Alc Depend. 2004;73:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mezzich AC, Tarter RE, Feske U, Kirisci L, McNamee RL, Bang-Shiuh Day BS. Assessment of risk for substance use disorder consequent to consumption of illegal drugs: Psychometric validation of the neurobehavior disinhibition trait. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:508–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Mezzich AC, Vanyukov M. Developmental trajectory classes in substance use disorder etiology. J Addict Behav. 2007;21:287–296. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Reynolds M, Habeych M. Relation between cognitive distortions and neurobehavior disinhibition on the development of substance use during adolescence and substance use disorder by young adulthood: a prospective study. Drug Alc Depend. 2004;76:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Reynolds M, Vanyukov M. Individual differences in childhood neurobehavior disinhibition predict decision to desist substance use during adolescence and substance use disorder in young adulthood. J Addict Behav. 2006;31:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Spirito A. Adolescents’ and their friends’ healthrisk behavior: Factors that alter or add to peer influence. J Pediatric Psychol. 2001;26:287–298. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell PA. Friends: The role of peer influence across adolescent risk behaviors. J Youth Adol. 2002;31:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musher-Eizenman DR, Holub SC, Arnett M. Attitude and peer influences on adolescent substance use: The moderating effect of age, sex, and substance. J Drug Educ. 2003;33:1–23. doi: 10.2190/YED0-BQA8-5RVX-95JB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer R, Williams B, Gibbon M. Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID; 4/1/87 rev.) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feske R, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Gao Z, Reynolds M, Vanyukov M. Peer environment mediates parental history and individual risk in the etiology of cannabis use disorder in boys: A 10-year prospective study. The Am J Drug and Alc Abuse. 2008;34:307–320. doi: 10.1080/00952990802013631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research (CEDAR) The Drug and Alcohol Use Chart. University of Pittsburgh; 1989. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarter RE. Evaluation and treatment of adolescent substance abuse: A decision tree method. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 1990;16:1–46. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4th edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacCallum RC, Browne, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loehlin JC. Latent Variable Models. 4th ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobel ME. Asymptomatic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverthorn P, Frick P. Developmental pathways to antisocial behavior: The delayed onset pathway in girls. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:101–126. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. Longitudinal follow-up adolescents with late onset antisocial behavior: A pathological yet overlooked group. J Amer Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychiat. 2005;44:1284–1291. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000181039.75842.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mezzich AC, Tarter RE, Giancola PR, Lu S, Kirisci L, Parks S. Substance use and risky sexual behavior in female adolescents. Drug Alc Dependence. 1997;44:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mezzich AC, Giancola PR, Lu S, Parks S, Ratica GM, Dunn M. Adolescent females with a substance use disorder: Affiliation with adult male sexual partner. The Am J Addictions. 1999;8:190–200. doi: 10.1080/105504999305802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE. Influence of deviant friends on delinquency: Searching for moderator variables. J Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:313–325. doi: 10.1023/a:1005188108461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Drugs and driving by American high school seniors 2001–2006. J Studies Alc. 2007;68:834–842. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loeber R. The Pittsburgh Youth Study. Department of Psychology: University of Pittsburgh, PA; 1989. [Google Scholar]