Abstract

Regulation of uteroplacental blood flow (UPBF) during pregnancy remains unclear. Large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa), consisting of α- and regulatory β-subunits, are expressed in uterine vascular smooth muscle (UVSM) and contribute to the maintenance of UPBF in the last third of ovine pregnancy, but their expression pattern and activation pathways are unclear. We examined BKCa subunit expression, the cGMP-dependent signaling pathway, and the functional role of BKCa in uterine arteries (UA) from nonpregnant (n = 7), pregnant (n = 38; 56–145 days gestation; term, ∼150 days), and postpartum (n = 15; 2–56 days) sheep. The α-subunit protein switched from 83–87 and 105 kDa forms in nonpregnant UVSM to 100 kDa throughout pregnancy, reversal occurring >30 days postpartum. The 39-kDa β1-subunit was the primary regulatory subunit. Levels of 100-kDa α-subunit rose ∼70% during placentation (P < 0.05) and were unchanged in the last two-thirds of pregnancy; in contrast, β1-protein rose throughout pregnancy (R2 = 0.996; P < 0.001; n = 13), increasing 50% during placentation and approximately twofold in the remainder of gestation. Although UVSM soluble guanylyl cyclase was unchanged, cGMP and protein kinase G1α increased (P < 0.02), paralleling the rise and fall in β1-protein during pregnancy and the puerperium. BKCa inhibition not only decreased UA nitric oxide (NO)-induced relaxation but also enhanced α-agonist-induced vasoconstriction. UVSM BKCa modify relaxation-contraction responses in the last two-thirds of ovine pregnancy, and this is associated with alterations in α-subunit composition, α:β1-subunit stoichiometry, and upregulation of the cGMP-dependent pathway, suggesting that BKCa activation via NO-cGMP and β1 augmentation may contribute to the regulation of UPBF.

Keywords: uteroplacental blood flow; regulatory subunits; protein kinase G isoforms; cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate

in mammalian species, fetal growth and well-being depend on successful placentation and the subsequent rise in maternal uteroplacental blood flow (UPBF) (31, 34–36). In sheep, UPBF increases >30-fold to >1,000 ml/min at term (34, 36, 41). This occurs in three steps (41). The first is preplacentation, when blood flow increases 100–150 ml/min and reflects vasodilation due to ovarian steroids (10–12, 36). This is followed by a further rise to ∼500 ml/min between 40 and 60 days of gestation, which is associated with angiogenesis and development of the maternal placental vascular bed (2, 32, 36, 41). In the final period, which occurs in the last two-thirds of pregnancy, UPBF rises to 1,000–1,500 ml/min by term and accounts for ∼25% of maternal cardiac output (34, 36, 41). This rise in UPBF is primarily vasodilation and an increase in maternal placental blood flow, which accounts for ∼90% of total UPBF by term (2, 35, 36, 52).

The mechanisms that contribute to the profound uterine vasodilation in the last two-thirds of pregnancy remain unclear. Uterine vascular synthesis of vasodilating prostaglandins, e.g., prostacyclin, increases in pregnant sheep (19, 20), but their inhibition does not alter basal UPBF (22, 25). Uterine vascular nitric oxide (NO) synthesis also increases, paralleling enhanced expression of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and synthesis of cGMP (7, 23, 39, 50, 57). However, acute uterine NOS inhibition decreases basal UPBF modestly (24, 39). Estrogen is a potent uterine vasodilator in nonpregnant and pregnant sheep (21, 36, 40) and is markedly elevated in pregnancy (4, 5), but its contribution to the rise in UPBF remains unclear. It is possible that each of these modulators contributes to the rise in UPBF, but their importance and the signaling cascades remain to be determined.

Large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa) are expressed in vascular smooth muscle (VSM) and modify vasorelaxation, vasoconstriction, and myogenic responses (16, 17, 27, 49, 51). They consist of four α-subunits that form the pore and are derived from the Slo gene and as many as four regulatory β-subunits that modify channel activity and sensitivity to activators, resulting in substantial channel diversity (3, 29, 55). The α-subunit may undergo posttranslational modifications, further adding to the functional diversity (16, 17, 49). At least four β-subunits exist, but β1 and β2 predominate in VSM (16, 17). BKCa contribute to estrogen- and NO-induced vasodilation in several vascular beds, including the ovine uterus (38, 44, 58), e.g., 17β-estradiol (E2) induces vasodilation via NO-induced increases in VSM cGMP and channel phosphorylation and/or directly activates the channel via the β1-subunit (9, 16, 17, 44, 53, 55). E2 also increases uterine VSM (UVSM) β1-subunit expression in nonpregnant ewes (26), which alters subunit stoichiometry and thus BKCa function. Furthermore, BKCa inhibition with tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) at concentrations ≤1 mM (27) has specificity for the channel and 0.35 mM decreases basal UPBF 70–80% in the last third of ovine pregnancy (43). Thus BKCa appear to be an excellent downstream candidate for regulating UPBF.

Although BKCa appear to contribute to UPBF regulation in pregnancy (38, 43), the expression pattern and subunit stoichiometry are unknown. Thus we examined 1) pregnancy-related changes in α-subunit isoform; 2) α- and β-subunit expression and stoichiometry in nonpregnant, pregnant, and postpartum ewes; 3) the cGMP-dependent signaling pathway for BKCa activation; and 4) the role of BKCa in UVSM relaxation-contraction responses.

METHODS

Tissue preparation.

Tissues were collected from seven nonpregnant, 38 pregnant (56–145 days gestation; term, ∼150 days), and 15 postpartum (2–54 days) sheep of mixed Western breed. Animals were euthanized with intravenous pentobarbital sodium (120 mg/kg). The abdomen was opened, the intact uterus was removed in block, and first and second generation uterine arteries were quickly dissected from both uterine horns and placed in sterile chilled physiological saline solution. While on ice, the adventitia and intraluminal blood were removed, and segments were opened along the long axis, and the endothelium was removed with a soft cotton swab, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C (26, 48). Additional samples were prepared for immunohistochemistry, as described below, while a 2.5–3.0 cm segment was placed in physiological salt solution of (in mM) 120.5 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 20.4 NaHCO3, 1.6 CaCl2, 10 dextrose, and 1.0 pyruvate at room temperature and transported within 30 min to the muscle physiology laboratory for contraction-relaxation studies. The studies described were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas.

Function studies.

Samples collected from six ewes at 54–58 days of gestation (the completion of placentation) and five at 142–146 days (term, ∼150 days) were used to study uterine artery function. Segments were cut into 4 to 5 mm rings, and the endothelium was removed by carefully turning the tip of a small forceps in the lumen. Endothelium removal was verified histologically, and the basal lamina and underlying VSM were intact. Each ring was placed on a stirrup attached to a transducer (Grass FT-03, Quincy, MA; and iWorx FT-302, Dover, NH) to measure force generation in a 25-ml volume chamber as previously reported (14, 45). The PBS containing (in mM) 120.5 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 20.4 NaHCO3, 1.6 CaCl2, 10.0 dextrose, and 1.0 pyruvate in the chamber was maintained at 37°C throughout the experiment by a circulating water pump. After a 30-min equilibration period, rings were progressively stretched to obtain optimal length (Lo), as determined with progressive increases in KCl-induced contractile responses with 65 mM KCl. Unresponsive rings were discarded. Studies with each ring were performed in duplicate. Dose-response curves were constructed at Lo with KCl (10–120 mM) and cumulative doses of phenylephrine (PE; 10−8 to 10−4.5 M), an α1-agonist, to examine nonreceptor and adrenergic receptor-mediated responses, respectively. To determine the role of BKCa in uterine artery contraction-relaxation responses, we employed the channel inhibitor TEA, which has specificity for the BKCa at concentrations ≤1.0 mM (27). Our laboratory previously used this agent to study channel function in intact sheep (38, 43, 44) and human uterine arteries (45). At the end of the dose responses and after returning to baseline, rings were exposed to 10−6 M PE followed by sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10−7 M), a NO donor, to obtain control contraction-relaxation responses with activated channels. The rings were washed and allowed to return to baseline tension for a minimum of 30 min. At that time, duplicate rings were exposed to one of three doses of TEA (0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mM) followed by 10−6 M PE, 10−7M SNP, and a wash as described above. In some instances, we examined the effect of PE alone after the first exposure to determine whether there was tachyphylaxis; this did not occur (P > 0.1). Data were recorded on an electronic data-acquisition system (Summit ACQuire and Summit DaStar; Gould Systems, Valley View, OH) in grams of force generated at Lo. The medial thickness and length of each segment was measured at the completion of studies, and responses were expressed as Newtons per squared meters (103 × N/m2).

Western blot analysis.

Samples of endothelium denuded uterine arteries (30 mg) were weighed and homogenized in 40× volumes of SDS buffer as previously described (26). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 2 min. The supernatant was removed, and an aliquot was used to determine cellular or soluble protein by BCA reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Bromophenol blue and 2-mercaptoethanol were added to aliquots, and equal amounts of soluble protein (20 or 30 μg) were loaded on 7.5% polyacrylamide minigels, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose paper at 100 V for 1 h. Blots were incubated overnight with antisera to the BKCa α-subunit (1:300; α1,098–1,196; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) and regulatory β-subunits using commercial antisera β1: (1:500; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), β2 (1:500; Calbiochem) and β4 (1:200; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel). After 1 h incubation with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2,000), immunoreactive protein was visualized by chemiluminescence. Samples were compared by scanning densitometry using arbitrary units. Ovine cerebellum was used as a positive internal control and nonimmune rabbit serum to show antibody specificity.

Placental estrogen synthesis increases during pregnancy, resulting in elevated circulating estrogen levels (4, 5). In nonpregnant ewes, daily E2 increases basal uterine blood flow, vascular synthesis of NO and cGMP, and BKCa activation (26, 43, 47). This is an important pathway for BKCa activation, which includes soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), cGMP, and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG1α) (13, 30, 33, 44, 56, 58). Thus we sought to determine whether there were changes in UVSM sGC, PKG1α, and PKG1β expression during the ovine reproductive cycle. We analyzed sGC (G4405; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), PKG1α (PK10; Calbiochem), and PKG1β (a gift from Dr. H. K. Surks, Tufts-New England Medical Center, Boston, MA) by immunoblot analysis using 1:1,000 or 1:750 dilution of specific antisera. Equal amounts of soluble protein (30 μg) were loaded on 10% polyacrylamide minigels, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and proteins were electrophoretically transferred to >nitrocellulose paper as described above.

cGMP assay.

Although uterine cGMP synthesis increases in pregnancy (39), it is unclear where the synthesis occurs and whether it is related to increases in UVSM sGC. Thus we measured UVSM cGMP contents by radioimmunoassay as previously described (48). Arteries were collected and frozen at −80°C. At the time of assay, samples were thawed, homogenized in 1 ml of 6% trichloroacetic acid, and spun at 2,500 g at 4°C for 15 min, and the supernatant was removed and assayed using the commercial radioimmunoassay (NEX-125; Perking Elmer, Boston, MA). Intra-assay variability was 1.3%, and inter-assay variability was 17%. The data are presented as picomoles per milligrams wet weight.

RT-PCR.

To examine the regulation of BKCa α- and β1-subunit expression in UVSM, we examined their respective mRNA using semiquantitative RT-PCR as previously reported (26). Denuded arterial samples were thawed in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) and homogenized, and total cellular RNA was extracted and resuspended in 20 μl 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate in water. The concentration and purity were measured at 260/280 nm optical density. RT was performed with 2 μg total RNA as previously described (39). The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 10 min, 37°C for 1 h, and terminated at 95°C for 5 min. PCR was performed on 2.5 μl of RT product (cDNA) with specific primers designed from nucleotide sequences retrieved from the GenBank (synthesized by Invitrogen Life Technologies). Malate dehydrogenase (MDH) was unchanged during pregnancy (P > 0.1, ANOVA) and was chosen as the reference gene to perform semiquantitative RT-PCR, normalizing values for BKCa α- and β1-subunit mRNA to MDH. The primers for MDH were: forward 5′-TCCCAGCAGCAACGGGTGT-3′ and reverse 5′-AAATCTTCGGGGTGACAACC-3′. BKCa α-subunit primers were: forward 5′-CAGCATTTGCCGTCAGTGTCCT-3′ and reverse 5′-CATGCCTTTGGGTTATTTTTCC-3′; β1-subunit primers were: forward 5′-TCACCTACTACATCCTGGTCACGA-3′ and reverse 5′-GGAATTTGGCTCTGACCTTCTCCA-3′. Conditions for the PCR reaction for the α- and β1-subunits were optimized, and analyses were performed as previously reported (39). To compare values, the targeted PCR products were run on the same gel.

Immunohistochemistry.

Intact segments of first and second generation uterine arteries were immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 h at room temperature and embedded in paraffin as previously described (26, 48). Sections were mounted on slides, deparaffinized, hydrated, incubated with avidin-biotin blocking agent for 30 min, and incubated overnight at room temperature with polyclonal antibodies to the BKCa α- or β1-subunits (1:30). After endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 3% H2O2 in H2O for 30 min, immunostaining was detected with standard streptavidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase and hematoxylin counter staining.

Statistical analyses.

Data were analyzed using linear and nonlinear regression analyses to examine overall changes across the reproductive periods and ANOVA to examine where within the time periods, e.g., pregnancy, changes occurred, using pairwise multiple comparison procedures. Student's t-test was used where appropriate. Data are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

BKCa α-subunit.

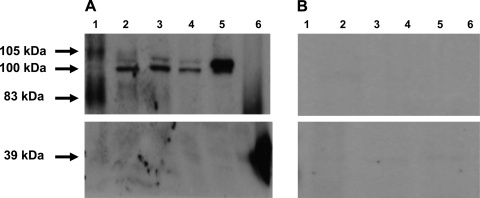

More than one isoform of the BKCa α-subunit has been reported, suggesting tissue-dependent expression of splice variants (16, 17, 26). We determined whether pregnancy alters the α-subunit species in UVSM and validated this by performing preabsorption studies with the peptide α1,098–1,196, which is a 39-kDa-specific protein moiety derived from the α-subunit and serves as a control for the immunoblots and the preabsorption studies. The predominant protein bands in nonpregnant uterine arteries were at 83–87 and 105 kDa with a minor band at 100 kDa (Figs. 1A and 2A); these bands were absent after preincubation (Fig. 1B). Notably, the 83–87 and-2 105-kDa protein species were not present during pregnancy, and the 100-kDa protein predominated (Figs. 1A and 2A) until >30 days postpartum, when the protein species were identical to those in nonpregnant UVSM (Fig. 2A). Again, all bands were absent after preabsorption (Fig. 1B). The sheep cerebellum had two bands at ∼100 kDa, resembling that seen in human, ovine, and mouse myometrium (26), which were also absent after preabsorption (Fig. 1B, lane 6). Importantly, the 39-kDa α-subunit peptide α1,098–1,196, which as noted above serves as a control, was also absent after preabsorption (Fig. 1B). Thus we used the 100-kDa band to determine changes in channel density and α-subunit expression during ovine pregnancy and to make comparisons before and after pregnancy.

Fig. 1.

Preabsorption studies of the protein variants of the large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa) α-subunit in first and second generation uterine artery smooth muscle and the effects of pregnancy. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of soluble protein (see methods). Lane representation is as follows: lane 1, nonpregnant; lanes 2 and 3, pregnant at 97 and 130 days gestation, respectively; lane 4, 25 days postpartum; lane 5, ovine cerebellum; and lane 6, α-subunit control peptide (α1,098–1,196), 50 μg. A: Western immunoblot without preabsorption. B: after preabsorption with the competing peptide. The 39-kDa protein in lane 6 was a positive control.

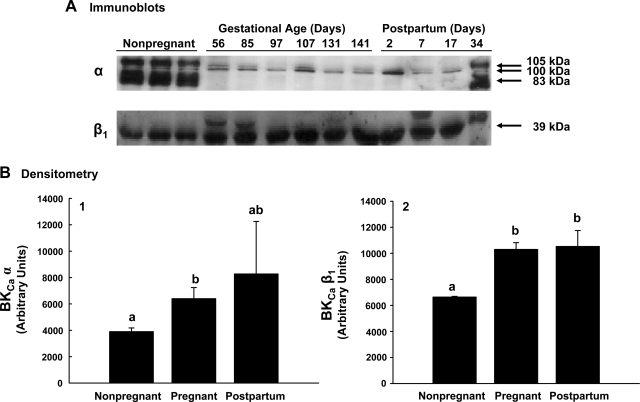

Fig. 2.

Representative immunoblots comparing the protein variants of BKCa α- and β1-subunits expressed in first and second generation uterine artery smooth muscle from nonpregnant (n = 3), pregnant (n = 6), and postpartum (n = 4) sheep. A: immunoblot analysis for subunit protein. B: analysis of densitometry in arbitrary units for the 100-kDa variant of the α-subunit (B.1) and 39-kDa β1 protein (B.2) during different reproductive periods. Values are means ± SE. Different letters represent differences between groups at P ≤ 0.05 by ANOVA; comparisons are on a single gel.

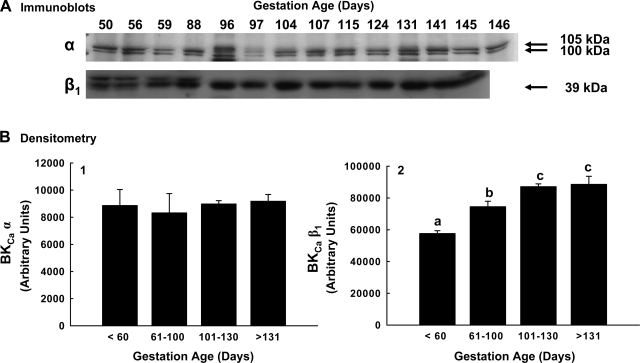

Comparisons of α-subunit expression between groups can only be accurately assessed on a single immunoblot. When UVSM protein from nonpregnant, pregnant, and postpartum ewes were examined on a single immunoblot, the 100-kDa protein in pregnant UVSM increased 64–81% compared with nonpregnant levels (P < 0.05, ANOVA; Fig. 2) but did not differ from arteries obtained at 2–17 days postpartum. To determine whether changes in α-subunit protein occurred during pregnancy, we performed a single immunoblot with samples obtained throughout the last two-thirds of pregnancy, i.e., 50–146 days (Fig. 3). There was no change in α-subunit protein during this time (R2 = 0.01; P = 0.8; n = 14).

Fig. 3.

Expression of the 100-kDa variant of the α-subunit and 39-kDa β1-subunit in first and second generation uterine artery smooth muscle in the last two-thirds of ovine pregnancy. A: immunoblot analysis for subunit protein. B: analysis of densitometry in arbitrary units for the 100-kDa α-subunit variant (B.1) and β1-subunit (B.2) during gestation; n = 3 to 4 for each time period. Values are means ± SE. For the α-subunit, P > 0.1 by ANOVA; regression analysis: R = 0.01, P = 0.9, n = 14. For the β1-subunit, different letters represent significant differences between groups at P < 0.001 by ANOVA.

BKCa β-subunit.

Four regulatory β-subunits are associated with the BKCa (16, 17, 55); however, they have not been systematically examined in all tissues and have not been studied during pregnancy. The β4-subunit was not detected in UVSM from any reproductive period. The β2-subunit was present in UVSM from all reproductive groups, but expression was minimal and unchanged (P > 0.1, data not shown). The β1-subunit was expressed as a single protein species at 39 kDa and was also present in UVSM from all reproductive groups (Figs. 2 and 3). The β1-subunit was first analyzed in samples from the three reproductive groups on a single immunoblot as described above. β1-protein increased >50% from nonpregnant to pregnant sheep, paralleling the rise in the α-subunit, but did not differ between pregnant and postpartum animals at 2–34 days (P < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 2). However, when the UVSM samples analyzed for the α-subunit during the last two-thirds of pregnancy were probed for β1 on a single immunoblot, β1-protein progressively rose between 50 and 146 days gestation (P < 0.001, ANOVA; Fig. 3B2). Notably, this rise was linear over the last two thirds of gestation (R2 = 0.996; P < 0.001; n = 13), and protein expression increased approximately twofold by term.

RT-PCR.

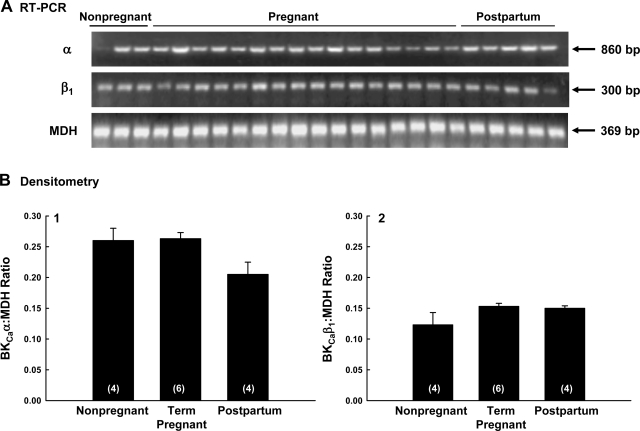

Using the same uterine artery samples analyzed for protein expression, we performed semiquantitative RT-PCR (see methods) across reproductive periods. There was no significant change in α- or β1-subunit mRNA before, during, or after pregnancy (Fig. 4B) when analyzed by regression analysis (R = 0.1; P ≥ 0.05; n = 23) or ANOVA (P > 0.1; Fig. 4, B1 and B2) after separating into groups of nonpregnant, term pregnant >135 days of gestation, and postpartum ≤30 days.

Fig. 4.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR for α- and β1-subunit mRNA in first and second generation uterine artery smooth muscle from nonpregnant (n = 4), pregnant (n = 6), and postpartum (n = 4) sheep. A: results of RT-PCR for the α- and β1-subunits and the reference gene malate dehydrogenase (MDH), which was unaffected by pregnancy (P > 0.1). B: densitometry of α- (B.1) and β1- (B.2) subunit mRNA in arbitrary units expressed as the ratio with MDH. There was no change in either subunit during the reproductive cycle by regression analysis (R = 0.1, P ≥ 0.05, n = 23) or ANOVA (P > 0.1) for multiple groups.

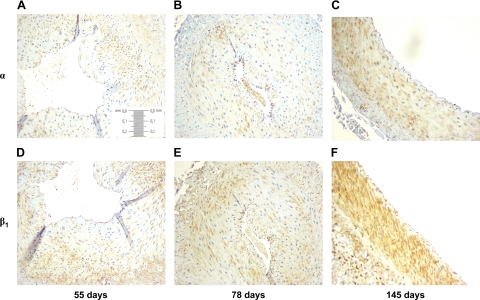

Immunohistochemistry.

To determine the site(s) of channel expression within the uterine artery wall and estimate relative channel density, we performed immunohistology for the α- and β1-subunits at 56, 78, and 146 days of gestation. There was no endothelial immunostaining for either subunit (Fig. 5). However, medial immunostaining for both subunits was evident throughout pregnancy, and the apparent intensity of immunostaining for both subunits increased over time; however, the immunostaining appears to be substantially greater and more diffuse for the β1-subunit at term.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry of first generation uterine arteries for BKCa α- and β1-subunit expression at 56 (A and D), 78 (B and E), and 146 (C and F) days of ovine gestation, respectively, at ×20 magnification.

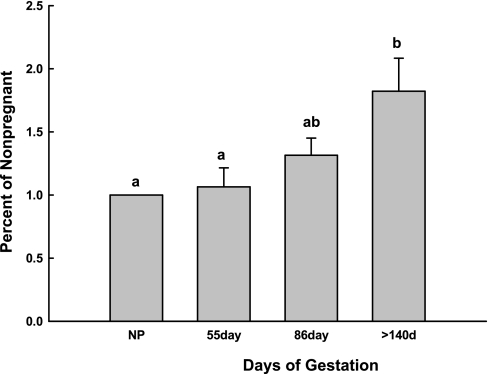

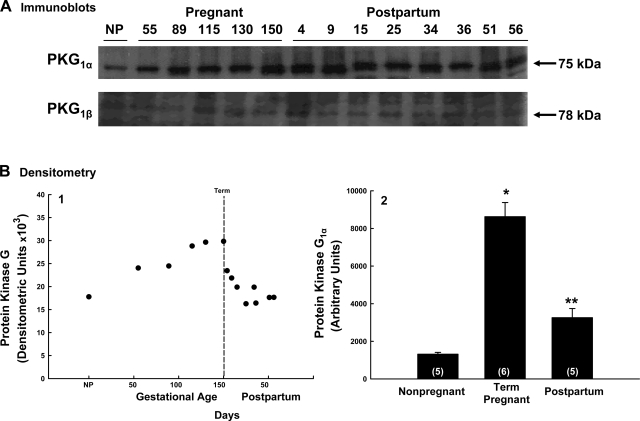

cGMP-dependent signaling.

Samples of denuded uterine artery obtained from each reproductive period were assayed for sGC, cGMP, PKG1α, and PKG1β protein. Although the levels of sGC protein were unchanged during the reproductive periods (R = 0.08; P = 0.8; n = 14; not shown), cGMP contents, expressed as a percentage of nonpregnant levels, gradually rose, with a transition at 86 days and an increase of >80% at term (P = 0.017, ANOVA; Fig. 6). PKG1β was present in all samples (Fig. 7A) but unchanged throughout the reproductive periods (P > 0.1; data not shown). In contrast, PKG1α protein increased nearly twofold by term (R = 0.86; n = 11; P = 0.002; Fig. 7B1) and decreased gradually after delivery, returning to nonpregnant levels by 30 days postpartum (R = 0.83; P = 0.008; n = 9). This was quantitatively analyzed by performing immunoblots with 5 to 6 samples each from nonpregnant, near-term pregnant, and 30–37 days postpartum ewes. There was a nearly sixfold rise in PKG1α protein by term gestation (P < 0.001; Fig. 7B2), followed by a 74% fall at 1 mo postpartum (P < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

The change in cGMP contents in first and second generation uterine artery smooth muscle during ovine pregnancy. Values are means ± SE expressed as levels relative to the average measured in 4 nonpregnant (NP) sheep, which serves as 100%. Different letters signify significant differences between groups at P < 0.017 by ANOVA. d, Day.

Fig. 7.

Effects of pregnancy and parturition on cGMP-dependent protein kinase 1α (PKG1α) and PKG1β expression in uterine artery vascular smooth muscle. A: immunoblot analysis for PKG1α and PKG1β protein. B: densitometry in arbitrary units for PKG1α protein. PKG1β was unchanged (P > 0.1, ANOVA). B1: pattern of PKG1α changed across reproductive periods, rising during pregnancy (R2 = 0.95, P < 0.001, n = 6) and falling during the puerperium (R2 = 0.83, P = 0.008, n = 9), achieving nonpregnant (NP) levels ≥30 days postpartum. B2: comparison of nonpregnant (n = 5), term pregnant (n = 6), and postpartum (n = 5) ewes at ∼30 days. *P < 0.001 comparing nonpregnant with term; **P < 0.001 for term vs. postpartum (t-test). Values are means ± SE.

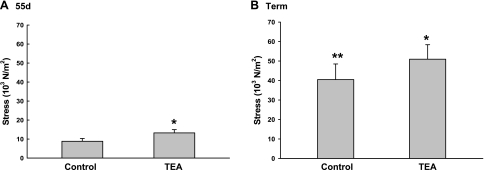

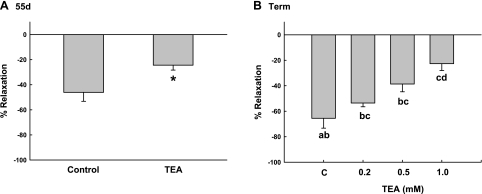

Channel function.

The role of BKCa in uterine artery function over the course of pregnancy is unknown. Since it may modulate both contraction and relaxation responses (16, 17, 27, 49, 51), we performed contraction-relaxation studies in segments of first generation denuded uterine artery rings at ∼55 days and ∼145 days gestation (term, ∼150 days), examining the effect of BKCa inhibition with TEA at ≤1.0 mM, doses that confer channel specificity (27). At both times in pregnancy, there were dose-dependent vasoconstrictor responses to KCl and PE (P < 0.001, ANOVA; data not shown); however, the control responses to 10−6 M PE at term exceeded those seen at 55 days, stresses increasing an additional 3.6-fold by term pregnancy (Fig. 8; P = 0.004). Although channel inhibition with 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mM TEA increased uterine artery responses to PE at both gestational ages (P < 0.05), there was no dose effect (P = 0.63). Thus we combined the data for further analyses. Following TEA exposure, PE responses were enhanced ∼50% at 55 days and ∼26% at term (P < 0.001). Although it appears that there might have been a time effect of channel inhibition on PE-induced contractions, this was not significant due to the variability in responses.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the effects of BKCa inhibition with tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) on phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions at 55 days (d; A) and term (B) gestation. *P < 0.001 compared with control by t-test; **P = 0.004 compared with control at 55 days gestation by t-test. Values are means ± SE. See Channel function for description of the analyses.

Knowing that NO might play a role in regulating UPBF, we then examined the relaxation responses of denuded uterine arteries to SNP, a NO donor, at both time points in pregnancy. In contrast with the contraction responses, there was no time- or gestational age-dependent difference in the control relaxation responses to SNP, stresses decreasing 47 ± 7% and 66 ± 8% (P = 0.7) in uterine arteries precontracted with 10−6 M PE at 55 days and term, respectively (Fig. 9). BKCa inhibition with TEA did not have a dose effect (P = 0.47) on NO-mediated relaxation at 55 days (Fig. 9A); however, TEA reduced relaxation responses ∼50%, 47 ± 7% vs. 24 ± 4% (P = 0.002, t-test). In contrast, at term, when uterine vasodilation is near maximum (36, 41), channel inhibition with TEA dose dependently (P < 0.001, ANOVA) reduced the relaxation responses 41% and 65% with 0.5 and 1.0 mM TEA, respectively.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of the effects of BKCa inhibition with TEA on nitroprusside-induced relaxation (10−7 M) after precontraction with 10−6 M PE at 55 days (d; A) and term (B) gestation. *P = 0.002 compared with control (C) by t-test. Different letters for groups in B signify significant differences at P < 0.001 by ANOVA. Values are means ± SE. See Channel function for description of the analyses.

DISCUSSION

Normal pregnancy is characterized by a marked rise in UPBF, levels increasing greater than thirtyfold by term gestation (34, 36, 41). The major component of this rise occurs in the last two-thirds of pregnancy and is primarily mediated by vasodilation (2, 36, 41, 52), but the underlying mechanisms are unclear. Recent evidence suggests several vasodilators contribute to the rise in UPBF, e.g., estrogen and NO, and may act through signaling pathways that activate BKCa (17, 38, 43, 57, 58). In the present study, we examined BKCa subunit expression and observed pregnancy-related modifications in the α-subunit resulting in a predominant 100-kDa isoform, the expression of which increases during placentation, but not thereafter. We also observed that the β1-subunit is the predominant regulatory subunit in UVSM, and its expression also increases during placentation; however, unlike the α-subunit, expression increases further during the last two-thirds of pregnancy, paralleling the rise in UPBF and altering channel stoichiometry. This was associated with increases in UVSM cGMP and cGMP-dependent kinase, PKG1α, as well as evidence that BKCa contribute to uterine artery contraction-relaxation responses. Notably, these changes are reversed at ≥30 days postpartum. These are the first data characterizing uterine artery BKCa expression during pregnancy and provide evidence of parallel enhancement of the cGMP-dependent pathway that might serve as a signaling pathway for progressive channel activation. Thus we present new insights into the role of BKCa in the rise in UPBF during pregnancy; however, the initiator of this signaling pathway has yet to be determined.

BKCa consist of four α-subunits encoded by the Slo gene that form the channel pore (16, 17, 49, 51). Several α-subunit isoforms have been reported and are believed to represent posttranslational modifications (16, 26, 49). However, this may reflect the techniques used for tissue collection and/or preparation for analysis. In the present study, tissues from all reproductive groups were similarly collected and prepared for study, and importantly, they were examined on the same immunoblot. There were three α-subunit species in nonpregnant UVSM, 83, 100, and 105 kDa, confirming an earlier report (26). During pregnancy, there was an absence of the 83-kDa protein and marked decrease in the 105-kDa protein, both reappearing ≥30 days after delivery, suggesting that some agent peculiar to pregnancy was involved. The preabsorption assays suggest that each isoform is likely derived from the α-subunit, again confirming earlier findings (26), and that they may represent unique posttranslational modifications of the α-subunit during ovine pregnancy. Alternatively, there may be selective increases in clearance or repression of the 83- and 105-kDa protein variants. Although the 100-kDa protein rose during placentation, this does not appear to equal the fall in the other two proteins, suggesting total channel density may actually fall in pregnancy. It is unclear what triggers the change in α-subunit, but estrogen is an unlikely candidate (26). It also is unclear whether this is unique to UVSM, since we did not study peripheral VSM. Notably, only the 83-kDa protein is seen in UVSM from older nonpregnant women (45). This could reflect age differences, the absence of estrogen, or changes unique to sheep. It is important to determine how these changes in the α-subunit occur and alter BKCa function.

The BKCa β-regulatory subunits are derived from separate gene products. β1 and β2 are associated with smooth muscle, whereas the others are primarily in nervous tissue (16, 17, 49, 55), explaining the absence of β4 in UVSM. β2 was present in ovine UVSM, but the levels were low and unchanged throughout the reproductive cycle. Interestingly, its expression is elevated in UVSM from older nonpregnant women, consistent with an age-related expression pattern (28, 45). Only a single species of the 39-kDa β1-subunit protein was seen, and it was highly expressed in each reproductive period. At the end of placentation, when UPBF has increased approximately fourfold, the relative increases in α- and β1-subunit are similar; thus β1:α stoichiometry may be unchanged. Unlike the α-subunit, β1-expression increased during the last two-thirds of gestation, paralleling the rise in UPBF. Although channel density may have been unchanged at this time, the stoichiometry is markedly altered, increasing the β1-to-α ratio. This difference in subunit expression pattern was evident in the immunohistochemistry by disproportionate changes in immunostaining. Our data for β1 mRNA suggest the rise in expression is posttranslational; however, the mechanisms responsible for the differences in subunit expression can only be speculated on at present. Since UPBF increases approximately fourfold during placentation (41), the proportionate rise in subunit protein in the proximal uterine arteries might be flow dependent (17). This, however, does not explain why the α-subunit is unchanged, whereas UPBF increases another threefold and the β1-subunit continues to increase. The latter may be due to increases in placental estrogen synthesis that begin with placentation and continue throughout the remainder of pregnancy (4, 5). This is supported by the finding that E2 selectively increases β1 expression in uterine arteries from nonpregnant ewes without altering the α-subunit (26) and evidence that placental estrogen is directly transferred to the uterine artery during pregnancy (18). These findings need further study.

The parallel rise in UPBF and β1-subunit permit enticing speculation about the regulation of UPBF in the last two-thirds of ovine pregnancy. Exogenous and endogenous estrogens are potent uterine vasodilators in nonpregnant and pregnant ewes (21, 40, 46, 47). This is mediated by increasing uterine artery NOS expression and activation, NO and cGMP synthesis, and BKCa activation (7, 23, 39, 44, 48, 50, 54, 57). Furthermore, estrogens activate BKCa directly via the β1-subunit (9, 17, 53). Thus one thesis is that placental estrogen accounts for the altered β1:α-subunit stoichiometry, which enhances channel activation and potentiates the direct effects of estrogen, resulting in BKCa-mediated vasodilation; conformation requires electrophysiological studies. Alternatively, placental estrogen increases uterine artery NOS, augmenting the NO-cGMP-PKG pathway, which increases BKCa phosphorylation and activation, thereby increasing UPBF (13, 30, 33, 55). Although UVSM sGC was unchanged, cGMP contents rose in the last two-thirds of pregnancy, suggesting enzyme activity increased (15). This was associated with increases in PKG1α protein by term, which could be activated by cGMP and in turn phosphorylate BKCa, accounting for the rise in UPBF that parallels the rise in the β1-subunit (13, 30, 33). PKG1β was present but unchanged. The presence of both PKG isozymes is not unusual (13, 56), but it is notable that PKG1α is activated by levels of cGMP tenfold less than that required for PKG1β (6). Thus the rise in PKG1α may amplify BKCa activation during pregnancy (30). A third possibility is that both pathways are upregulated, representing a redundancy that insures the rise in UPBF during the period of exponential fetal growth. Irrespective of the signaling pathways involved, local BKCa inhibition with TEA decreases UPBF 70–80% in the last third of ovine pregnancy, supporting the thesis that the BKCa is a major regulator of basal UPBF (43). The challenge is to determine which pathway can be manipulated to develop therapeutic strategies to reverse decreases in UPBF seen in abnormal pregnancies, e.g., maternal hypertension (31, 35).

BKCa modify and contribute to contraction-relaxation responses in VSM (16, 17, 27). This was examined in uterine artery rings at 55 days and term. There was a gestational age-related increase in PE responses consistent with earlier studies that suggest that α-stimulation is an essential mechanism for maintaining UVSM tone in pregnancy (1, 8, 37). Importantly, BKCa inhibition with TEA enhanced the contraction responses to PE, suggesting BKCa modify adrenergic responses and may contribute to the attenuated uterine vascular adrenergic responses seen in normal pregnant women and sheep (36, 43) and possibly the myogenic responses observed by Cox et al. (8). BKCa inhibition also decreased relaxation responses to NO at both ages, but at term it was dose dependent, suggesting an age-related increased role in NO-mediated uterine vasodilation. These findings are strikingly similar to those recently seen in vascular rings from nonpregnant women (45) and in intact pregnant sheep (42).

In the present study we characterized UVSM BKCa expression during the ovine reproductive cycle, identifying alterations in the pore-forming α-subunit that persisted throughout pregnancy and disappeared when ewes began to cycle. β1-subunit expression increased, altering channel stoichiometry and possibly enhancing BKCa resting potential, activation, and function and contributing to the regulation and rise in UPBF. Although the NO-cGMP-PKG1α pathway was upregulated, its contribution is unclear, as are other proximal signaling events. It is possible placental estrogen modifies channel expression and activation. The potential for pharmacological intervention in the presence of a decrease in UPBF has not previously existed but may be in the horizon if a similar system exists in women.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD-008783-33 (awarded to C. R. Rosenfeld) and the George L. MacGregor Professorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Annibale DA, Rosenfeld CR, Kamm KE. Alterations in vascular smooth muscle contractility during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 256: H1281–H1288, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowicz PP, Arnold DR, Johnson ML, Grazul-Bilska AT, Redmer DA, Reynolds LP. Placental growth throughout the last two thirds of pregnancy in sheep: vascular development and angiogenic factor expression. Biol Reprod 76: 259–267, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ. Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407: 870–876, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnegie JA, Robertson HA. Conjugated and unconjugated estrogens in fetal and maternal fluids of the pregnant ewe: possible role for estrogen sulfate during early pregnancy. Biol Reprod 19: 202–211, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challis JRG, Harrison FA, Heap RB. Uterine production of oestrogens and progesterone at parturition in sheep. J Reprod Fertil 25: 306–307, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang S, Hypolite JA, Velez M, Changolkar A, Wein AJ, Chacko S, DiSanto ME. Downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-1 activity in the corpus cavernosum smooth muscle of diabetic rabbits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R950–R960, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad KP, Joffe GM, Kruszyna R, Kruszyna H, Rochelle LG, Smith RP, Chavez JE, Mosher MD. Identification of increased nitric oxide biosynthesis during pregnancy in rats. FASEB J 7: 566–571, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox BE, Roy TA, Rosenfeld CR. Angiotensin II mediates uterine vasoconstriction through α-stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H126–H134, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Wet H, Allen M, Holmes C, Stobbart M, Lippiat JD, Callaghan R. Modulation of the BK channel by estrogens: examination at single channel level. Mol Membr Bio 23: 420–429, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford SP Control of uterine and ovarian blood flow throughout the estrous cycle and pregnancy of ewes, sows and cows. J Anim Sci 55: 32–42, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson TC, Phernetton TM, Wiltbank MC, Magness RR. Development and use of an ovarian synchronization model to study the effects of endogenous estrogen and nitric oxide on uterine blood flow during ovarian cycles in sheep. Biol Reprod 70: 1886–1894, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greiss FC, Anderson SG. Uterine vascular changes during the ovarian cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 103: 629–640, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofmann F The biology of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases. J Biol Chem 280: 1–4, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutanu C, Cox BE, DeSpain K, Liu XT, Rosenfeld CR. Vascular development beginning in early ovine gestation: carotid smooth muscle function, phenotype, and biochemical markers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R323–R333, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh H, Bird IM, Nakao K, Magness RR. Pregnancy increases soluble and particulate guanylate cyclases and decreases the clearance receptor of natriuretic peptides in ovine uterine, but not systemic arteries. Endocrinology 138: 3329–3341, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korovkina VP, England SK. Detection and implications of potassium channel alterations. Vascul Pharmacol 38: 3–12, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledoux J, Werner ME, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone. Physiology 21: 69–79, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magness RR, Ford SP. Steroid concentrations in uterine lymph and uterine arterial plasma of gilts during the estrous cycle and early pregnancy. Biol Reprod 27: 871–877, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magness RR, Mitchell MD, Rosenfeld CR. Uteroplacental production of eicosinoids in ovine pregnancy. Prostaglandins 39: 75–88, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magness RR, Osei-Boaten K, Mitchell MD, Rosenfeld CR. In vitro prostacyclin production by ovine uterine and systemic arteries: effects of angiotensin II. J Clin Invest 76: 2206–2212, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR. Local and systemic estradiol-17β: effects on uterine and systemic vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 256: E536–E542, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR, Faucher DJ, Mitchell MD. Uterine prostaglandin production during ovine pregnancy: effects of angiotensin II and indomethacin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 263: H188–H197, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magness RR, Shaw CE, Phernetton TM, Zheng J, Bird IM. Endothelial vasodilator production by uterine and systemic arteries. II. Pregnancy effects on NO synthase expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H1730–H1740, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller SL, Jenkin G, Walker DW. Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on the uterine vasculature of the late-pregnant ewe. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180: 1138–1145, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naden RP, Iliya CA, Arant BS Jr, Gant NF Jr, Rosenfeld CR. Hemodynamic effects of indomethacin in chronically instrumented pregnant sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 151: 484–493, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagar D, Liu XT, Rosenfeld CR. Estrogen regulates the β1-subunit of the BKCa channel in uterine vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1417–H1427, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C799–C822, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura K, Eghbali M, Lu R, Marijie J, Stephanie E, Toro L. Functional and molecular evidence of MaxiK channel β1 subunit decrease with coronary artery aging in the rat. J Physiol 559: 849–862, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orio P, Latorre R. Differential effects of β1 and β2 subunits on BK channel activity. J Gen Physiol 125: 395–411, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng W, Hoidal JR, Farrukh IS. Regulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells: role of nitric oxide. J Appl Physiol 81: 1264–1272, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynolds LP, Caton JS, Redmer DA, Grazul-Bilska AT, Vonnahme KA, Boroxicz PP, Luther JS, Wallace JM, Wu G, Spencer TE. Evidence for altered placental blood flow and vascularity in compromised pregnancies. J Physiol 572: 51–58, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds LP, Redmer DA. Angiogenesis in the placenta. Biol Reprod 64: 1033–1040, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberston BE, Schubert R, Hescheler J, Nelson MT. cGMP-dependent protein kinase activates Ca-activated K channels in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 265: C299–C303, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenfeld CR Distribution of cardiac output in ovine pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 232: H231–H235, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenfeld CR Consideration of the uteroplacental circulation in intrauterine growth. Semin Perinatol 8: 42–51, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenfeld CR The Uterine Circulation. Ithaca, NY: Perinatology Press, 1989, p. 1–312.

- 37.Rosenfeld CR Mechanisms regulating angiotensin II responsiveness by the uteroplacental circulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1025–R1040, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenfeld CR, Cornfield DN, Roy T. Ca2+-activated K+ channels modulate basal and E2-induced rises in uterine blood flow in ovine pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H22–H31, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenfeld CR, Cox BE, Roy T, Magness RR. Nitric oxide contributes to estrogen-induced vasodilation of the ovine uterine circulation. J Clin Invest 98: 2158–2166, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenfeld CR, Morriss FH Jr, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Effects of estradiol-17β on blood flow to reproductive and nonreproductive tissues in pregnant ewes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 124: 618–629, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenfeld CR, Morris FH Jr, Makowski EL, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Circulatory changes in the reproductive tissues of ewes during pregnancy. Gynecol Invest 5: 252–268, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenfeld CR, Roy TA. Large conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (BKCa) contribute to attenuated uterine vascular responses to α-stimulation in pregnant sheep (Abstract). Reprod Sci 14: 110A, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenfeld CR, Roy T, DeSpain K, Cox BE. Large-conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels regulate basal uteroplacental blood flow in ovine pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig 12: 402–408, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenfeld CR, White RE, Roy T, Cox BE. Calcium-activated potassium channels and nitric oxide coregulate estrogen-induced vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H319–H328, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenfeld CR, Word RA, DeSpain K, Liu Xt. Large conductance Ca+2-activated K+ channels contribute to vascular function in nonpregnant human uterine arteries. Reprod Sci 15: 651–660, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenfeld CR, Worley RJ, Gant NF Jr. Uteroplacental blood flow and estrogen production following dehydroisoandrosterone infusion. Obstet Gynecol 50: 304–307, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenfeld CR, Worley RJ, Milewich L, Gant NF Jr, Parker CR Jr. Ovine fetoplacental sulfoconjugation and aromatization of dehydroepiandrosterone. Endocrinology 106: 1971–1979, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salhab WA, Shaul PW, Cox BE, Rosenfeld CR. Regulation of type I and type III nitric oxide synthases by daily and acute estrogen exposure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H2134–H2142, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 921–931, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sladek SM, Magness RR, Conrad KP. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R441–R463, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanaka Y, Koike K, Toro L. MaxiK channel roles in blood vessel relaxation induced by endothelium-derived relaxing factors and their molecular mechanisms. J Smooth Muscle Res 40: 125–153, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teasdale F Numerical density of nuclei in the sheep placenta. Anat Rec 185: 181–196, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valverde MA, Rojas P, Amigo J, Cosmelli D, Orio P, Bahamonde MI, Mann GE, Vergara C, Latorre R. Acute activation of maxi-K channels (hSlo) by estradiol binding to the β subunit. Science 285: 1929–1931, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Buren GA, Yang DS, Clark KE. Estrogen-induced uterine vasodilation is antagonized by l-nitroarginine methyl ester, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 124: 618–629, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Ding JP, Xia X, Lingle CJ. Consequences of the stoichiometry of Slo1 α and auxiliary β subunits on functional properties on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J Neurosci 22: 1550–1561, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weber S, Bernhard D, Lukowski R, Weinmeister P, Wörner R, Wegener JW, Valtcheva N, Feil S, Schlossmann J, Hofmann F, Feil R. Rescue of cGMP kinase I knockout mice by smooth muscle-specific expression of either isoenzyme. Circ Res 101: 1096–1103, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiner CP, Tompson LP. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 21: 367–380, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White RE, Darkow DJ, Lang JL. Estrogen relaxes coronary arteries by opening BKCa channels through a cGMP-dependent mechanism. Circ Res 77: 936–942, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]