Abstract

Therapeutic strategies in which recombinant growth factors are injected to stimulate arteriogenesis in patients suffering from occlusive vascular disease stand to benefit from improved targeting, less invasiveness, better growth-factor stability, and more sustained growth-factor release. A microbubble contrast-agent-based system facilitates nanoparticle deposition in tissues that are targeted by 1-MHz ultrasound. This system can then be used to deliver poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles containing fibroblast growth factor-2 to mouse adductor muscles in a model of hind-limb arterial insufficiency. Two weeks after treatment, significant increases in both the caliber and total number of collateral arterioles are observed, indicating that the delivery of nanoparticles bearing fibroblast growth factor-2 by ultrasonic microbubble destruction may represent an effective and minimally invasive strategy for the targeted stimulation of therapeutic arteriogenesis.

Keywords: arteriogenesis, drug delivery, microbubbles, nanoparticles, ultrasound

1. Introduction

Growth factors known to be critical regulators of vascular remodeling[1–5] are often used in therapeutic revascularization strategies,[6–8] particularly vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)[9–10] and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2).[11–12] However, despite the potential shown by growth-factor administration in stimulating therapeutic arteriogenesis in animal models and small clinical trials, more-comprehensive clinical trials have highlighted fundamental challenges that must be addressed before growth factors are confidently applied in clinical settings. In particular, there is a considerable need to optimize the mode of growth-factor delivery so that the impact on systemic tissues is minimal, the bioactivity of the growth factor is retained, and the local concentration of delivered growth factor in tissue is sustained over time.[13]

Owing to advances in polymer chemistry, therapeutic and diagnostic, the number of polymeric biomaterials applications has grown substantially.[14–15] Biopolymer-based drug-delivery strategies, including those centered on the release of vascular growth factors,[16–18] are likely to have utility in cardiovascular applications.[19–20] Inparticular, poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), a biodegradable, biocompatible, and FDA-approved material, has been widely used in a variety of therapeutic applications, including the controlled release of drugs.

In numerous animal models and tissues, our group and others have shown that the destruction of circulating contrast-agent microbubbles with low-frequency ultrasound can selectively increase microvessel permeabilization such that circulating materials extravasate into tissue.[21–23] Therefore, contrast-agent microbubbles, conventionally used as signal-enhancing agents in diagnostic ultrasound imaging,[24] hold considerable promise as tools for targeting the delivery of therapeutic genes,[25–26] growth factors,[27–28] and cells[29–31] to ultrasound-targeted tissues.

In the study described herein, we tested whether ultrasonic microbubble destruction could be used in conjunction with biodegradable polymer nanoparticle drug-delivery vehicles to stimulate arteriogenesis in a mouse model of hind-limb ischemia. We first established that ultrasonic microbubble destruction effectively transfers circulating 100-nm-diameter nanoparticles into the gracilis hind-limb adductor muscle. Next, we fabricated 100-nm-diameter nanoparticles composed of biodegradable PLGA and loaded them with FGF-2. After performing an in vitro assay to ensure that FGF-2 remained biologically active following nanoparticle fabrication, the FGF-2-loaded nanoparticles were intravascularly co-administered with microbubbles, and ischemic mouse hind limbs were exposed to pulsed 1-MHz ultrasound. One and two weeks after treatment, FGF-2-treated, bovine serum albumin (BSA) control, and sham surgery control gracilis adductor muscles were assessed for angiogenic and arteriogenic remodeling.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Targeted Nanoparticle Delivery with Ultrasound-Microbubble Treatment

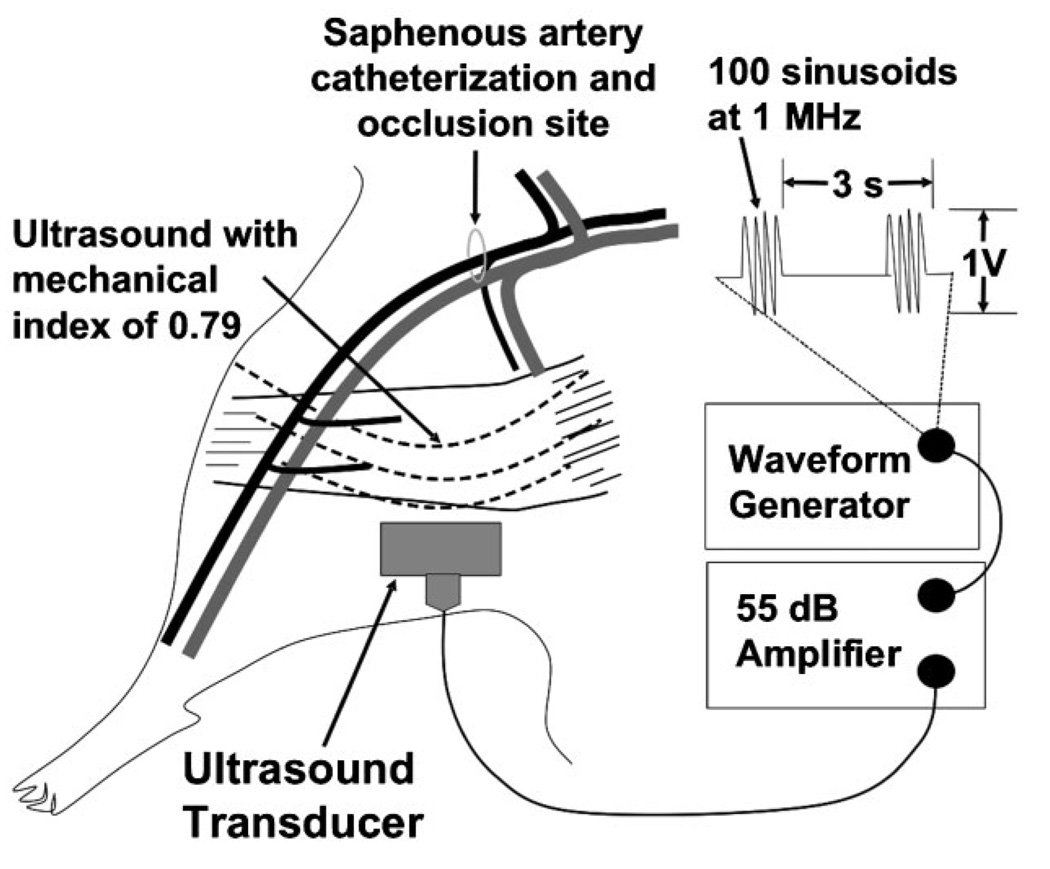

In the study discussed herein, we first established that ultrasonic microbubble destruction effectively transfers circulating 100-nm-diameter nanoparticles into the gracilis hind-limb adductor muscle. To this end, we visualized muscles immediately after microbubbles and 100-nm red-fluorescent polystyrene or green-fluorescent PLGA nanoparticles had been coadministered and ultrasound had been applied as illustrated schematically in Figure 1. As seen in low-magnification photomicrographs in Figure 2, 100-nm nanoparticles were distributed throughout the ultrasound-targeted muscle. The deposition of red-fluorescent polystyrene nanoparticles in the interstitial spaces between muscle fibers and in endothelial cells is shown in cross-sections in Figure 3. From these sections, endothelial cell and interstitial areas were quantified, and the fractions of these areas containing nanoparticles were determined (Figure 3J). In this case, we observed that the complete treatment (i.e. ultrasound+microbubble+nanoparticle) significantly augmented the deposition of nanoparticles into these regions, with nanoparticles covering 33% of the endothelial area and 27% of the interstitial area. These values are, respectively, 40-fold and 670-fold higher than in the microbubble -+nanoparticle control group in which no ultrasound was applied. In previous studies, we concluded that the transmural pressure difference between the capillary lumen and the interstitial space facilitates the transport of nanoparticles into the interstitial space by convective transport,[21–22] and it is probable that the same mechanism is operative in this case. Importantly, Vancraeynest et al.[23] showed that ultrasonic microbubble destruction also permits colloidal particle delivery to myocardium, indicating that this effect is not limited to skeletal muscle. In addition, we have shown previously that selected ultrasound and microbubble parameters can be modified to enhance delivery of submicron particles into the interstitial space,[22] which may prove to be important for optimizing this method in the future.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the mouse hind-limb model including the site of the saphenous artery catheter insertion and occlusion, the region of tissue exposed to ultrasound, and the ultrasound parameters used throughout the study.

Figure 2.

Ultrasonic microbubble destruction transfers circulating nanoparticles (NPs) into gracilis muscle. Representative bright-field (A and C) and fluorescence (B and D) images of muscles receiving 100-nm-diameter fluorescent polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles (A and B) and PLGA nanoparticles loaded with FITC-conjugated BSA (C and D) are shown. Arrows indicate the saphenous vein (SV) in each image. Gracilis muscles are labeled “GM”.

Figure 3.

Muscle cross-sections illustrating nanoparticle (NP) delivery for each treatment. A–I: Representative images of sections taken from gracilis muscles treated with ultrasound (US)+microbubbles (MB)+nanoparticles (NP) (A, B, C), ultrasound + nanoparticles (D, E, F), and microbubbles + nanoparticles (G, H, I) are shown. Note the deposition of nanoparticles (red) in vessel walls (BS-1 lectin staining, green) and the interstitium of the muscle treated with ultrasound + microbubble + nanoparticle. The muscle treated with ultrasound + nanoparticle exhibits colocalization of nanoparticles with endothelium but minimal interstitial deposition. The muscle section treated with microbubble + nanoparticle is almost void of nanoparticles. J: Bar graph representing the fraction of interstitial area (regions outside of muscle fibers and vascular structures) or endothelial cell area (cells comprising the walls of blood vessels) occupied by fluorescent polystyrene nanoparticles. Values are means with standard deviations. * indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than interstitial area of all other groups. +indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than endothelial cell area of all other groups.

Interestingly, applying ultrasound to circulating nanoparticles alone (i.e. the ultrasound+nanoparticle group) elicited significant colocalization of the nanoparticles with the endothelium. Because control muscles that were not exposed to ultrasound contained only trace amounts of nanoparticles (Figure 3), we are confident that this colocalization of nanoparticles and the endothelium was not an artifact caused by incomplete perfusion of the muscle with heparinized saline after treatment. Unfortunately, because the size of the nanoparticles is well below the resolution of standard microscopy, it is not possible to establish firmly whether ultrasound in the absence of microbubbles actually transferred the nanoparticles to the intracellular compartment and/or caused them to adhere to the luminal endothelial surface. In support of the hypothesis that ultrasound alone can facilitate intracellular delivery, it was previously shown that ultrasound alone transiently disrupts cell membranes,[32–33] potentially facilitating nanoparticle transport to the cytoplasm. It is also possible that primary radiation forces exerted on the circulating nanoparticles elicit their margination to the vessel wall, where they may then be actively endocytosed by endothelial cells.[34]

2.2. Characterization of FGF-2 Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles

Next, we adapted a water-in-oil-in-water method[34] to fabricate 100-nm-diameter nanoparticles composed of biodegradable PLGA and loaded them with FGF-2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images confirmed that the PLGA nanoparticles had a spherical structure (Figure 4A). Quantification of nanoparticle size with a submicron-particle analyzer revealed a mean nanoparticle diameter of ≈100nm (Figure 4B). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to illustrate the release profile of FGF-2 from nanoparticles at 37 °C (Figure 4C). To confirm that FGF-2 retains its bioactivity after being encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles, FGF-2 and BSA control nanoparticles were incubated for 48 h in the basolateral chambers of transwells with human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) plated on their apical surfaces. In this case, we observed a sevenfold increase in the migration of HMVECs exposed to FGF-2 nanoparticles relative to BSA nanoparticles (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Characterization of PLGA nanoparticles loaded with FGF-2. A: Representative scanning electron micrographs of PLGA nanoparticles confirming the mean diameter of the nanoparticles to be ≈100 nm. B: Representative size distribution of PLGA nanoparticles measured with a submicron-particle analyzer. C: Kinetics of FGF-2 release from PLGA nanoparticles over a 7-day period. D: Bar graph of FGF-2-bioactivity assay showing the percentage of total transwell surface area covered by endothelial cells. Values are means with standard deviations. *indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than BSA.

2.3. FGF-2-Bearing Nanoparticles Delivered to Skeletal Muscle by Ultrasonic Microbubble Destruction Markedly Amplify Arteriogenesis

We then determined whether the delivery of FGF-2-loaded nanoparticles to tissue by the destruction of microbubbles with ultrasound could be used to stimulate arteriogenesis. In this study, FGF-2 nanoparticles were intravenously co-injected with microbubbles into mice whose hind limbs had been made ischemic by placing a ligature around the femoral artery. Ischemic hind limbs were exposed to pulsed 1-MHz ultrasound, and the animals were allowed to recover. After either 1 or 2 weeks, animals were euthanized and the hind-limb adductor muscles were harvested.

BS-1 lectin staining was perfomed on cross-sectioned muscles to visualize the capillaries and to assess angiogenesis. Figure 5A and B shows BS-1 lectin+ microvessel profiles in sections from BSA control and FGF-2-treated muscles 7 days after treatment. At both days 7 and 14, the number of capillaries per unit muscle area was unchanged between gracilis muscles treated with FGF-2 nanoparticles and muscles treated with BSA control nanoparticles (Figure 5C), indicating that the FGF-2 treatment had no effect on angiogenesis. However, in terms of therapeutic efficacy, we believe the lack of angiogenesis created by FGF-2 nanoparticles in the upper hind limb is of little concern because, owing to both their anatomical positioning and the fact that they terminate in venules, capillaries in the upper hind limb cannot serve as collateral pathways capable of supplying arterial blood to the lower hind limb. Instead, the luminal expansion of pre-existing arterioles most effectively augments blood flow to distal capillary beds.[35]

Figure 5.

FGF-2 released from nanoparticles delivered by ultrasonic microbubble destruction does not induce angiogenesis in gracilis muscle. A, B: Representative images of BS-1-lectin-labeled microvessels in sections from A) BSA control and B) FGF-2-treated gracilis muscles at 7 days after treatment. C: Bar graph of BS-1 lectin + microvessel densities of FGF-2-treated and BSA-control gracilis muscles at days 7 and 14. Values are means with standard errors. No significant differences were observed.

Whole-mount gracilis muscles were also immunolabeled for SM α-actin to visualize the arterioles and assess arteriogenesis. Representative images of SM α-actin+ vessels within whole gracilis muscles are shown for the FGF-2 and BSA groups at days 7 and 14 in Figure 6A–D. Notably, the arteriolar density and caliber in the FGF-2 muscles (Figure 6A and B) increase substantially relative to BSA control muscles (Figure 6C and D). Fourteen days after FGF-2 nanoparticle delivery by ultrasonic microbubble destruction, gracilis muscles exhibited a significant 22% increase in arteriole-line intersections over BSA controls and a significant 46% increase in arteriole-line intersections over sham surgery controls (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

The delivery of FGF-2bearing nanoparticles by ultrasonic microbubble destruction elicits arteriogenic remodeling in gracilis adductor muscle. A–D: Representative whole-mount images of fluorescently-labeled SM α-actin+ vessels in gracilis adductor muscles 7 and 14 days after FGF-2 (A and B) and BSA (C and D) treatment. Note the significant increase in arteriolar caliber and density in FGF-2-treated muscles. E: Bar graph of arteriole-line intersections at both time points for FGF-2, BSA, and sham surgery treatment. Values are means with standard errors. *indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than BSA and sham surgery at day 14.

SM α-actin-labeled whole-mount gracilis adductor muscles were also used to assess the maximum diameters of arterioles at selected locations (Figure 7A). At day 14, the transverse arterioles (TAs) in FGF-2-treated muscles were ≈33% greater in diameter than the TAs in both the BSA control and sham surgery control muscles (Figure 7B). Whereas no statistically significant differences in anterior collateral(AC)diameter were observed between the FGF-2 and BSA control groups (Figure 7C), AC diameters were approximately twofold greater in the FGF-2 group than in the sham surgery controls. The most dramatic arteriogenic response occurred in the posterior collateral (PC) artery at day 14, with PC diameters in the FGF-2 group being 133% and 82% greater than sham surgery and BSA control diameters, respectively. Of note, at day 14, the BSA control group exhibited an increase in both AC and PC diameter relative to the sham surgery control group.

Figure 7.

The delivery of FGF-2-bearing nanoparticles by ultrasonic microbubble destruction significantly augments the maximum luminal diameter of arteries and arterioles. A: Schematic illustration of a gracilis adductor muscle with diameter measurement sites demarcated with “AC” for anterior collateral, “PC” for posterior collateral, and “TA” for transverse arteriole. B–D: Bar graphs of transverse arteriole diameters (B), anterior collateral diameters (C), and posterior collateral diameters (D) for FGF-2-treated, BSA control, and sham surgery control groups at 7 and 14 days after treatment. Values are means with standard errors. *indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than BSA at same time. **indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than FGF-2 at day 7. +indicates significantly different (P<0.05) than sham surgery at same time.

Recently, we showed that ultrasonic microbubble destruction alone is sufficient to induce vascular remodeling in normal[36–37] and ischemic[38] skeletal muscle. These findings were confirmed by other investigators who showed similar proarteriogenic responses in skeletal muscle treated with microbubbles and ultrasound.[29–31] Although the results from these earlier studies suggest that this method holds promise, it is unclear as to whether the arteriogenic responses created by ultrasonic microbubble destruction alone can generate clinically significant tissue reperfusion. For example, although we have shown significant luminal expansion of large arterioles and enhanced hyperemia in rats,[37–38] these studies were performed in the presence of only moderate[38] or non-existent[37] arterial insufficiency. Furthermore, we did not observe a large vessel arteriogenesis response in non-ischemic mouse skeletal muscle,[36] indicating that the response may be species-dependent. Thus, there is some uncertainty about the potential for translation to humans. In addition, with regard to flow restoration, other investigators have reported contradictory results. For example, Yoshida et al.[31] showed increased flow in ischemic mouse hind limbs at 1 and 2 weeks after ultrasonic microbubble destruction, but Leong-Poi et al.[26] reported no increase in flow with ultrasonic microbubble destruction unless the treatment was accompanied by the delivery of the gene for vascular endothelial growth factor165 (VEFG165). Given this uncertainty, we developed the strategy described herein, which provides two separate but complementary stimuli for arteriogenesis: 1) bioeffects induced by ultrasonic microbubble destruction that trigger a baseline response and facilitate nanoparticle deposition, and 2) the sustained release of FGF-2 from the delivered biodegradable nanoparticles which serves to amplify the baseline response.

The method described herein has several features that may enhance its potential for successful clinical translation. These include minimally invasive targeting, sustained growth-factor delivery, and retention of growth-factor bioactivity. Other investigators have taken advantage of the targeting ability of ultrasonic microbubble destruction to deliver genes for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)[25] and VEGF[26,39] to the heart and skeletal muscle for subsequent stimulation of neovascularization. Because tissues were transfected with growth-factor genes,[25,26,39] local levels of bioactive growth factor protein were elevated in the targeted tissue as long as the gene was expressed. Although this represents a clear improvement over strategies in which a bolus of soluble recombinant growth factor protein is directly injected into the tissue, there are still potential disadvantages to gene therapy. These include high degradation rates of genetic material in vivo, unpredictable and/or transient gene expression, and a requirement that the cells be healthy enough to incorporate and express the gene.[40] In contrast, both the release rate and the local concentration of bioactive growth factor from polymer nanoparticles may be controlled by altering polymer molecular weight and end-cap chemistry, and there are fewer uncertainties created by poor cell viability. On the other hand, one disadvantage of using nanoparticles that bear growth factor protein is that they are considerably more expensive to produce than plasmid-conjugated microbubbles. Because of this cost factor, the delivery of inexpensive and easily synthesized small-molecule inducers of angiogenesis, instead of recombinant growth factors, may ultimately be a more cost-effective solution.

We chose FGF-2 as our stimulus because it has been strongly implicated as a proarteriogenic factor[3] that is amenable to controlled-release delivery.[41] For example, Hosaka et al.[41] used FGF-2 in an arterially injected formulation comprised of 29-µm gelatin hydrogel micro-spheres, demonstrating an increase in smooth-muscle-coated vessels in a rabbit ischemic hind-limb model. The advantage of their strategy, in which larger microspheres were intentionally lodged in the arterioles, is that the entire FGF-2 dose was delivered to the limb. In contrast, our FGF-2-bearing controlled-release nanoparticles were concentrated in the limb by using ultrasonic microbubble destruction. Our strategy undoubtedly allows some FGF-2-bearing nanoparticles to pass through the limb and into the systemic venous circulation as a result of their small size, and an advantage to our approach is that there is no need to titrate the doses to ensure that the arterial circulation of the limb remains acutely patent. Importantly, although we used different arteriogenesis metrics, in general, we achieved results that were similar to those reported by Hosaka et al.[41]. Specifically, we determined that the posterior collateral arterial vessel within the gracilis adductor muscle experienced a >80% enhancement in diameter over the BSA nanoparticle-treated control (Figure 7D), which based on the 4th-power relationship between vessel diameter and flow, translates into an ≈11-fold increase in flow capacity for this vessel. Additional evidence for the ability of this method to reduce arterial resistance in the upper hind limb is provided in Figure 6E and Figure 7B, in which we report an increase in the total density of arterioles that are >15µm in diameter, as well as a significant increase in mean transverse arteriolar diameter.

3. Conclusions

We and others have shown that ultrasonic microbubble destruction induces microvessel disruptions that permit intravascular constituents to be transferred into both the endothelium and interstitium of ultrasound-exposed tissues.[21–23] This unique feature of ultrasonic microbubble destruction has been harnessed to target the delivery of therapeutic genes,[25–26] growth factors,[27,28] and cells.[29–31] Herein, we applied this technology to therapeutic arteriogenesis. After verifying that ultrasonic microbubble destruction effectively deposits intravascular nanoparticles into mouse adductor skeletal muscle, we generated FGF-2-bearing biodegradable PLGA nanoparticles, coadministered them intraarterially with microbubbles, and targeted their delivery to ischemic mouse hind limbs with ultrasound. The delivery of the FGF-2-bearing nanoparticles stimulated appreciable arteriogenic remodeling in ischemic mouse hind-limb adductor muscles. This response included an increase in the total number of large and moderate diameter arterioles (i.e. >15µm in diameter), as well as a marked luminal expansion of both the preexisting collateral arteries and the transverse arterioles. Ultimately, these results indicate that ultrasonic microbubble destruction has potential as a platform for the minimally invasive therapeutic delivery of proarteriogenic nanoparticles.

4. Experimental

Microbubble Preparation

Octafluoropropane gas (Flura, Newport, TN) was layered above a 1% solution of serum albumin in normal saline in a flask. To create microbubbles, the solution was sonicated for 30 s with an ultrasound disintegrator (XL2020, Misonix, Farmingdale, NY) equipped with an extended 1/2″ titanium probe. Mean microbubble diameter, as determined with a Multisizer Coulter Counter, was 2.63±1.63µm.

Nanoparticle delivery to gracilis muscle by ultrasonic microbubble destruction

All animal experiments were in compliance with an animal protocol approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Eighteen weight-matched wild-type c57BL/6J mice were distributed into three treatment groups: ultrasound + microbubble + nanoparticle (n=8), ultrasound + nanoparticle (n=5), and microbubble + nanoparticle (n=5). Mice were anesthetized by continuous inhalation of an isoflurane/oxygen mixture and secured to a stage warmed to 37 °C. After depilation of the ventral surface of the right hind limb, the skin was surgically reflected back, and a catheter was inserted into the external iliac artery and secured with sutures, thereby facilitating the intraarterial administration of microbubbles and/or nanoparticles. The microbubble + nanoparticle solution consisted of microbubbles (0.10 mL, 1.6×109 microbubbles mL−1), polystyrene nanoparticles (0.13 mL, 1.0×1013 microbubblesmL−1, Duke Scientific, Palo Alto, CA), and heparinized saline (0.07mL) and was injected over 120 s by using an injection pump (Sage Instruments, Cambridge, MA). The nanoparticle solution administered to the hind limbs that were exposed only to ultrasound (i.e. ultrasound + nanoparticle group) was composed of nanoparticles (0.13 mL) and heparinized saline (0.17 mL). Furthermore, instead of receiving polystyrene nanoparticles, three mice from the ultrasound + microbubble + nanoparticle group received nanoparticles composed of poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and loaded with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated bovine serum albumin (FITC–BSA). Ultrasound coupling gel was placed inbetween the hind limb and the transducer. Ultrasound (1MHz, 1 V peak-to-peak) was transmitted at the start of the injection with pulses applied every 3 s for 150 s. To control for the effects of the ultrasound energy on nanoparticle deposition, the microbubble + nanoparticle group received the solution injection; however, the transducer positioned over the hind limb was never activated. Moreover, to ensure that nanoparticles observed in the treated tissues were indeed physically deposited into the vessel wall or interstitium and not simply present residually, an additional volume of heparinized saline (0.10 mL) was administered through the catheter, and blood was allowed to recirculate through the treated tissues.

Assessment of nanoparticle delivery to gracilis adductor muscle

Immediately after treatment, mouse hind-limb muscles were imaged under bright-field and fluorescent illumination with a Microfire digital camera (Olympus America, Melville, NY) mounted on a Zeiss microscope with a 4× objective and in conjunction with PictureFrame software (Optronics Corp., Muskogee, OK). After the imaging, the animals were sacrificed, and the muscles were suffusion fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%) for 30 min, excised, and placed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To gain insight into the spatial distribution of the nanoparticles in the muscle relative to the vasculature, muscles were incubated in 1:200 biotin-conjugated Bandeiraea simplicifolia (BS)-1 lectin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in saponin (0.1%) and BSA (2%) over 3 nights. After one wash with PBS for 60 min and two washes for 30 min, the specimens were soaked in a solution of 1:1000 AlexaFluor488-conjugated streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in saponin (0.1%) and BSA (2%) to visualize the microvessels. Whole mount muscles were digitally imaged with a confocal scanner (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and these images were combined to form a complete image of the muscle. After confocal imaging, these muscles were snap-frozen and prepared for cryosectioning with a cryotome. Fifteen micron-thick sections were taken from both the lateral and medial regions of the muscles, mounted on slides, and sequentially relabeled with 1:200 biotin-conjugated BS-1 lectin (overnight, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 1:1000 AlexaFluor488–streptavidin (1 h, Molecular Probes). Images of sections taken by confocal microscopy were combined into full-section montages and processed with threshold and calculation functions by using Corel PHOTO-PAINT 11 (Corel Inc., Dallas, TX) to assess the fraction of endothelial cell and interstitial projected area occupied by nanoparticles.

Fabrication of PLGA nanoparticles bearing fibroblast growth factor-2

Prior to nanoparticle fabrication, a 2% solution of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (Acros Organics, Morris Plains, NJ) was made by dissolving PVA (20 g) in H2O (1000 mL) with low heat. On the day of nanoparticle fabrication, dichloromethane (50 µL, CH2Cl2, D37-500, Fisher Scientific) was added to the PVA solution (2%, 24 mL). The PVA+MC solution was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant collected to remove undissolved PVA. A polymer solution was made by dissolving high-molecular-weight 85:15 uncapped PLGA (90 mg, Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL) in CH2Cl2 (6 mL) in a glass scintillation vial. An aqueous solution of BSA (15 mg, Jackson Laboratories) and heparin (4.5 mg, H3393, 170 USP units/mg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS (1.5mL) was added and vortexed. The PLGA+CH2Cl2 solution was placed in an ice bath for 5 minutes and then sonicated at 45W for 150 s with using a high-power sonicator (Misonix S-3000 Sonicator, Farmingdale, NY). The PLGA+CH2Cl2 solution was added in two portions with intermittent vortexing to the PVA solution (24 mL) in a 50-mL conical tube. The new PVA+CH2Cl2+PLGA solution was placed on an ice bath for 5 min and then sonicated again with 60W of energy for 150 s. This solution was stirred overnight. After 24 h, the suspension of nanoparticles was stirred in a vacuum desiccator for 1 h. The suspension was then transferred into a thick-walled polycarbonate centrifuge open-top tube (355631, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) and centrifuged at 27000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge (Optima L-90K Ultracentrifuge, rotor: SW-28, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Palo Alto, CA). After discarding the supernatant, the pellet was resuspended in distilled water and sonicated for 30 s. The resulting solution was centrifuged again at 27000 rpm for 17 min at 4 °C, pouring off the supernatant after centrifugation. The nanoparticle solution was resuspended again in distilled water (10 mL) and sonicated for 30 s. To remove large aggregates, the nanoparticle solution was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. A sample of the nanoparticle suspension was analyzed by a submicron-particle sizer (Multisizer IIe, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) and by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The supernatant was collected, frozen at −70 °C for 45 min, and lyophilized for 2 days. The dry nanoparticle powder was stored in a desiccator at 4 °C until needed. PLGA nanoparticles (2 mg) were soaked with gentle agitation overnight in a solution of heparin (100 µg), BSA (25 mg), and recombinant FGF-2 (25 µg, 233-FB, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in PBS (5 mL). This solution was frozen at −70 °C for 45 min and lyophilized for 2 days. The resulting dry powder of FGF-2-loaded nanoparticles was stored in a dessicator at 4 °C until needed.

Kinetics of FGF-2 release from PLGA nanoparticles

FGF-2-loaded PLGA nanoparticles (0.5 mg) were suspended in PBS (1 mL, pH 7.4) in microcentrifuge tubes that were then placed in a 37 °C water bath. At selected times, the tubes were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 30 min, and the supernatant from each tube was collected. To simulate the release conditions for the in vivo experiments, in which FGF-2-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were resuspended ≈4 h before treatment, the baseline measurement (i.e. t=0) was taken after the nanoparticles had been in solution for 4 h. Precipitated nanoparticles were resuspended in fresh PBS (1 mL) and returned to the water bath. The mass of FGF-2 in each aliquot of supernatant was determined by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Invitrogen).

In vitro FGF-2-bioactivity assay

Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) were cultured in microvascular endothelial cell medium-2 (EGM-2 MV, CC-3202, Lonza Walkersville Inc., Walkersville, MD). At passage 10 or 11, HMVECs (6 × 104 cells cm−2) were plated on the apical surface (0.33 cm2) of a transwell permeable support system (6.5-mm diameter, 24-well plate, 0.8-µm pore size, Corning Costar No. 3422, 07-200-150, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) in normal culture medium with 5% serum. After the cells were allowed to adhere for 4 h, the culture medium in the basolateral chamber was removed and replaced with a new culture medium (500 µL) containing FGF-2-loaded or BSA-loaded nanoparticles (ca. 10 mg). Transwells were placed in an incubator for 48 h to maintain a temperature of 37 °C and CO2 levels of 5% and to allow FGF-2 release from the degrading nanoparticles. After 48 h, media from both chambers was removed, and cells adhering to the top of the transwell membrane were mechanically dislodged and washed with PBS (1 mL). After removing the PBS, a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde (600µL) was added to each well and incubated at −20 °C for 30 min. The paraformaldehyde was aspirated off, and the fixed cells were washed once more in PBS. Cells fixed to the bottom transwell membrane were stained with crystal violet (600 µL) for 15 min and then washed in distilled water. After drying overnight, the basolateral surface of the transwell was imaged with a Microfire digital camera mounted on a Wild Makroskop inverted microscope (Model M420, Leica, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) and in conjunction with PictureFrame software. Images of migrated cells on the basolateral side of the transwell were analyzed with Corel PHOTO-PAINT11. The area occupied by cells was found in pixels by creating a binary image of this region and then applying a threshold. The total area of this isolated region was also found in pixels. These two measurements yielded an overall percentage of cell area per total well area.

FGF-2 nanoparticle delivery in the ischemic hind-limb model

Sixteen weight matched wild-type c57BL/6J mice were randomly distributed into four experimental groups. Two treatment groups (n=4 per group at days 7 and 14) received FGF-2 nanoparticles, and two control groups received BSA nanoparticles (n=4 per group at days 7 and 14). Each animal was anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and maintained at 37 °C throughout experimentation. Under sterile conditions, the skin over each right hind limb was reflected back, and the saphenous artery was catheterized. A heparinized saline solution (0.1%) containing microbubbles and nanoparticles loaded with either FGF-2 (5 µgmL−1, 0.13 mL) or BSA (5 mg mL−1, 0.13 mL) was administered through the saphenous artery catheter while ultrasound pulses were transmitted every 3 s (see Figure 1) for 120 s. After removal of the catheter, the right saphenous artery was fully occluded and bisected, thereby establishing a model of unilateral hind-limb ischemia. Two additional sham control groups (n=4 at day 7 and n=5 at day 14) were also created. Mice in these groups were exposed to the surgical procedures described above; however, the right saphenous artery was not ligated and nanoparticles were not injected.

Seven or 14 days after treatment, the gracilis muscles were surgically exposed and superfused with Ringer’s solution containing adenosine (10−4 M) to create maximal vasodilation. Gracilis muscles were then harvested immediately after being suffusion-fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%) in saline (0.9%). Whole-mount muscles were immunochemically labeled for smooth muscle (SM) α-actin. Whole-muscle montages that had been generated from confocal images were used to measure arteriole diameters, and the number of intersections between arterioles >15 µm in diameter and 7 lines were drawn perpendicular to the muscle fiber direction to generate a metric of arteriolar density. In addition, FGF-2-treated and BSA-control muscles were cryosectioned and labeled with Bandeiraea simplicifolia (BS)-1 lectin so that the ratio of BS-1 lectin+ vessels to muscle area could be determined. Detailed immunochemistry, imaging, and measurement procedures are provided in the Supporting Information.

Immunohistochemistry methods for cross-sections and whole mounts

Following overnight incubation in 1:200 Cy3-conjugated monoclonal anti-smooth muscle (SM) α-actin (clone 1A4; Sigma) and three PBS-saponin washes, whole muscles were imaged at 4× by digital microscopy. Whole-muscle montages were reconstructed from individual fields-of-view and analyzed as described in the section below. Whole-mounted muscles were then cryosectioned and incubated with 1:200 AlexaFluor488-BS-1 lectin (Molecular Probes). After three PBS-saponin washes, sections were mounted for confocal imaging.

Whole-muscle image analysis for arteriogenesis

Montaged images of SM α-actin vascular networks within whole muscles were opened with Scion Image (NIH) software. Arterioles with diameters >15 µm in diameter were identified based on the intensity of SM α-actin staining and morphology. Seven lines were then drawn perpendicular to the muscle fiber direction and equally spaced from the saphenous artery to the muscular branch. The total number of intersections between these 7 lines and the previously identified >15-µm diameter arterioles was then counted for each specimen.

Individual diameter measurements were made by using a distance measurement function in the Scion Image software. The diameter of an individual vessel was found by measuring the distance of SM α-actin staining perpendicular to the longitudinal vessel direction. For each specimen, arteriole diameter measurements were taken at several prescribed locations. Mouse gracilis muscles contain two major collateral arterioles, denoted here as the anterior collateral (AC) arteriole and the posterior collateral (PC) arteriole, that span the entire muscle (Figure 5 and Figure 6). AC and PC diameters were measured in three places (i.e. at each edge of the muscle and in the center of the muscle). These three measurements were then averaged to yield a single diameter value for each AC and PC within each specimen. Transverse arterioles (TAs) arise from the AC and PC to supply capillary units in the gracilis muscle. The root diameters of the most distal and medial TAs along each collateral artery were measured. These four values were then averaged to yield a single TA diameter value per muscle.

Muscle section image analysis for angiogenesis

Prepared sections were viewed with a Nikon TE-300 inverted microscope and a 20× PlanFluor objective. A confocal scanner was used to obtain digital images of every field-of-view within each section. CorelPHOTO-PAINT 11 was used to combine fields-of-view for each section into a montage, creating a complete image of the muscle section. Scion Image was used to quantify vessel profiles positively marked with BS-1 lectin and muscle fibers in each section. These measurements facilitated assessment of BS-1 lectin+ vessel profiles per muscle fiber, a metric that indicates the nature of the angiogenic remodeling response.

Statistical analysis

All data were first tested for normality. Interstitial and endothelial nanoparticle deposition data (Figure 3J) were analyzed by One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by pairwise comparisons with Tukey’s t-tests. A Student’s t-test was used to compare transwell data (Figure 4D). All angiogenesis and arteriogenesis data (Figure 5–Figure 7) were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons with Tukey’s t-tests. Significance was assessed at P<0.05 for all studies. All statistical procedures were performed by using SigmaStat version 3.11 software (Sigma-Stat Software, SPSS; Chicago, IL).

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants to Dr. Price from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL74082) and the American Heart Association (Grant-in-Aid 0555511U). The authors wish to thank Dr. Edward Botchwey and his laboratory for providing the human microvascular endothelial cells and for technical assistance with the in vitro assays.

Contributor Information

John C. Chappell, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Robert M. Berne, Cardiovascular Research Center, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville VA, 22908 (USA) Fax: (+1) 434-982-3870

Ji Song, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Robert M. Berne, Cardiovascular Research Center, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville VA, 22908 (USA) Fax: (+1) 434-982-3870.

Caitlin W. Burke, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Robert M. Berne, Cardiovascular Research Center, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville VA, 22908 (USA) Fax: (+1) 434-982-3870

Alexander L. Klibanov, Email: alk6n@virginia.edu, University of Virginia, Cardiovascular Medicine and Robert M. Berne, Cardiovascular Research Center, Box 800500, Health System, Charlottesville VA, 22908 (USA) Fax: (+1) 434-982-3183.

Richard J. Price, Email: rprice@virginia.edu, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Robert M. Berne, Cardiovascular Research Center, Box 800759, Health System, Charlottesville VA, 22908 (USA) Fax: (+1) 434-982-3870.

References

- 1.Risau W. Nature. 1997;386:671. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, Declercq C, Pawling J, Moons L, Collen D, Risau W, Nagy A. Nature. 1996;380:435. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deindl E, Hoefer IE, Fernandez B, Barancik M, Heil M, Strniskova M, Schaper W. Circ Res. 2003;92:561. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000061181.80065.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Royen N, Hoefer I, Buschmann I, Heil M, Kostin S, Deindl E, Vogel S, Korff T, Augustin H, Bode C, Piek JJ, Schaper W. FASEB J. 2002;16:432. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0563fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown DM, Hong SP, Farrell CL, Pierce GF, Khouri RK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luttun A, Tjwa M, Moons L, Wu Y, Angelillo-Scherrer A, Liao F, Nagy JA, Hooper A, Priller J, De Klerck B, Compernolle V, Daci E, Bohlen P, Dewerchin M, Herbert JM, Fava R, Matthys P, Carmeliet G, Collen D, Dvorak HF, Hicklin DJ, Carmeliet P. Nat Med. 2002;8:831. doi: 10.1038/nm731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morishita R, Sakaki M, Yamamoto K, Iguchi S, Aoki M, Yamasaki K, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Lawn R, Ogihara T, Kaneda Y. Circulation. 2002;105:1491. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012146.07240.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Pawliuk R, Wariaro D, Post MJ, Wahlberg E, Leboulch P, Cao Y. Nat Med. 2003;9:604. doi: 10.1038/nm848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry TD, Annex BH, McKendall GR, Azrin MA, Lopez JJ, Giordano FJ, Shah PK, Willerson JT, Benza RL, Berman DS, Gibson CM, Bajamonde A, Rundle AC, Fine J, McCluskey ER. Circulation. 2003;107:1359. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061911.47710.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedman M, Hartikainen J, Syvanne M, Stjernvall J, Hedman A, Kivela A, Vanninen E, Mussalo H, Kauppila E, Simula S, Narvanen O, Rantala A, Peuhkurinen K, Nieminen MS, Laakso M, Yla-Herttuala S. Circulation. 2003;107:2677. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070540.80780.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laham RJ, Sellke FW, Edelman ER, Pearlman JD, Ware JA, Brown DL, Gold JP, Simons M. Circulation. 1999;100:1865. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons M, Annex BH, Laham RJ, Kleiman N, Henry T, Dauerman H, Udelson JE, Gervino EV, Pike M, Whitehouse MJ, Moon T, Chronos NA. Circulation. 2002;105:788. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simons M, Ware JA. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:863. doi: 10.1038/nrd1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Nature. 2004;428:487. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen RR, Silva EA, Yuen WW, Mooney DJ. Pharm Res. 2007;24:258. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perets A, Baruch Y, Weisbuch F, Shoshany G, Neufeld G, Cohen S. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;65:489. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Q, Chen RR, Shen Y, Mooney DJ, Rajagopalan S, Grossman PM. Pharm Res. 2005;22:1110. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-5644-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokolsky-Papkov M, Agashi K, Olaye A, Shakesheff K, Domb AJ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:187. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price RJ, Skyba DM, Kaul S, Skalak TC. Circulation. 1998;98:1264. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.13.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song J, Chappell JC, Qi M, VanGieson EJ, Kaul S, Price RJ. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:726. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vancraeynest D, Havaux X, Pouleur AC, Pasquet A, Gerber B, Beauloye C, Rafter P, Bertrand L, Vanoverschelde JL. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:237. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schutt EG, Klein DH, Mattrey RM, Riess JG. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:3218. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo I, Ohmori K, Oshita A, Takeuchi H, Fuke S, Shinomiya K, Noma T, Namba T, Kohno M. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:644. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leong-Poi H, Kuliszewski MA, Lekas M, Sibbald M, Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Klibanov AL, Stewart DJ, Lindner JR. Circ Res. 2007;101:295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Z, Mukherjee D, Wang K, Zhou X, Tarakji K, Ellis K, Chan AW, Penn MS, Ostensen J, Thomas JD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:396. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwasaki M, Adachi Y, Nishiue T, Minamino K, Suzuki Y, Zhang Y, Nakano K, Koike Y, Wang J, Mukaide H, Taketani S, Yuasa F, Tsubouchi H, Gohda E, Iwasaka T, Ikehara S. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1589. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enomoto S, Yoshiyama M, Omura T, Matsumoto R, Kusuyama T, Nishiya D, Izumi Y, Akioka K, Iwaoc H, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J. Heart. 2005;92:515. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imada T, Tatsumi T, Mori Y, Nishiue T, Yoshida M, Masaki H, Okigaki M, Kojima H, Nozawa Y, Nishiwaki Y, Nitta N, Iwasaka T, Matsubara H. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2128. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000179768.06206.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida J, Ohmori K, Takeuchi H, Shinomiya K, Namba T, Kondo I, Kiyomoto H, Kohno M. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:899. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlicher RK, Radhakrishna H, Tolentino TP, Apkarian RP, Zarnitsyn V, Prausnitz MR. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:915. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.02.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crowder KC, Hughes MS, Marsh JN, Barbieri AM, Fuhrhop RW, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:1693. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davda J, Labhasetwar V. Int J Pharm. 2002;233:51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00923-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholz D, Ziegelhoeffer T, Helisch A, Wagner S, Friedrich C, Podzuweit T, Schaper W. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:775. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chappell JC, Klibanov AL, Price RJ. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:1411. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song J, Qi M, Kaul S, Price RJ. Circulation. 2002;106:1550. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028810.33423.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song J, Cottler PS, Klibanov AL, Kaul S, Price RJ. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00144.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korpanty G, Chen S, Shohet RV, Ding J, Yang B, Frenkel PA, Grayburn PA. Gene Therapy. 2005;12:1305. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ylä-Herttuala S, Alitalo K. Nat Med. 2003;9:694. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosaka A, Koyama H, Kushibiki T, Tabata Y, Nishiyama N, Miyata T, Shigematsu H, Takato T, Nagawa H. Circulation. 2004;110:3322. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147779.17602.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]